Abstract

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) are primary bone neoplasms that rarely involve the skull base. These lesions are usually locally aggressive and require complete removal, including the surrounding apparently healthy bone, to provide the best chance of cure. GCTs, as well as other lesions located in the clivus, can nowadays be treated by a minimally invasive fully endoscopic extended endonasal approach. This approach ensures a more direct route to the craniovertebral junction than other possible approaches (transfacial, extended lateral, and posterolateral approaches). The case reported is a clival GCT operated on by an extended endonasal approach that provides another contribution on how to address one of the most feared complications attributed to this approach: a massive bleed due to an internal carotid artery injury.

Background

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) are primary bone lesions that usually involve the metaphyseal region of long bones in the appendicular skeleton. Although classified as benign entities, they can be locally aggressive and metastasize distant to the primary site of origin.Citation1,Citation2 Cranial lesions are rare and usually arise from the skull base rather than the vault.Citation3–Citation7 Due to the small number of skull base GCTs reported in the literature, recommendations on treating this type of lesion are still unclear, and the role of surgery, as well as adjuvant therapies, remains undefined.Citation8–Citation10 Complete tumor removal and drilling of the surrounding apparently healthy bone are preferable in order for patients to expect a complete clinical cure and a reduced recurrence rate, even though this approach implies a higher risk of intraoperative complications and neurologic impairments.

Historically performed through challenging open approaches, treatment of lesions located in the craniovertebral junction (CVJ) can nowadays be reached by less invasive procedures, such as the endoscopic extended endonasal approach (EEA).Citation11–Citation14 We report a case of a clival GCT completely resected by a fully endoscopic EEA but complicated by an intraoperative tearing of the internal carotid artery (ICA). Injury to the ICA during endonasal surgery is the most feared and catastrophic complication that could happen during an EEA, and control of the surgical field is very challenging.Citation15–Citation19

A review of the literature demonstrates that there is a lack of information with regard to the appropriate techniques and protocols in managing an ICA injury during endonasal surgery. This paper describes how to remove even large clival GCTs with adequate bony margins and how we treated the ICA injury.

Case presentation

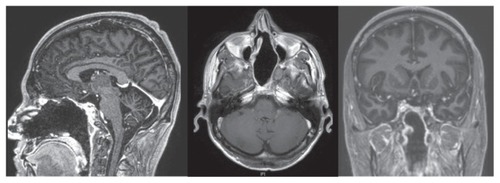

A 31-year-old male was admitted to our hospital because of progressive headache and diplopia. Neurologic and vision examination revealed a right sixth cranial nerve palsy and double vision in the right lateral view only. Other cranial nerves were normal, as were visual field and acuity. The patient was fully cooperative and orientated without motor or sensory deficits, cerebellar tests were performed correctly, and the general state of his health was good. Brain magnetic resonance imaging and an angio-computed tomography scan showed a large osseous extradural lesion originating from the clivus, compressing both cavernous sinuses, and expanding into the nasal cavity and sphenoid sinus with erosion of the sellar floor. The ICAs were lateralized and upward dislocated, the dural layer was respected, and the brainstem was not compressed (). Laboratory tests and chest X-ray were normal.

Figure 1 Sagittal, axial, and coronal magnetic resonance images showing a large giant cell tumor originating from the clivus and involving both cavernous sinuses.

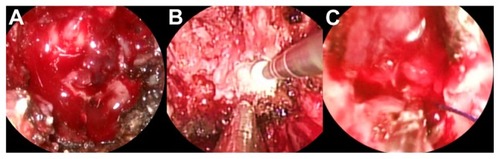

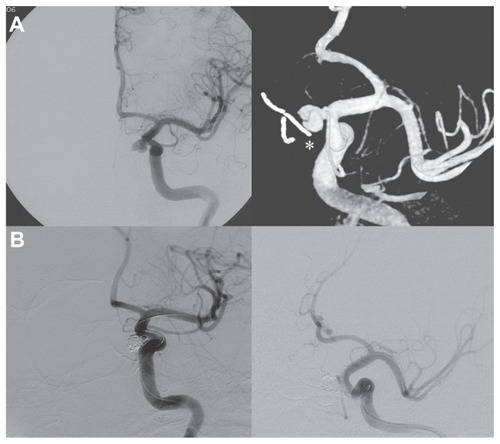

The patient was operated on by a fully endoscopic neuro-navigation guided EEA. The lesion was completely removed, but during the drilling of the surrounding healthy bone there was a little tearing of the left ICA. Local control of the bleeding was challenging, but it was obtained by using topic hemostatic agents and leaving microcottonoids adhering to the artery fissuration (). An insufflate balloon catheter for nasal tamponade was put into the nasal cavity. The intraoperative tearing of the ICA led us to perform an immediate postoperative angiography, disclosing a pseudoaneurysm originating near the inferior meningohypophyseal trunk, which was successfully treated by embolization with coils ().

Figure 2 Endoscopic intraoperative images showing the erosion of the sphenoid bone by the tumor (A), the drilling of the apparently healthy bone near the carotid region (B), and the microcottonoid adhering to the artery fissuration (C).

Figure 3 (A) Internal carotid artery angiography demonstrating the pseudoaneurysm originating near the inferior meningohypophyseal trunk and the microcottonoid adhering to the internal carotid artery fissuration (white asterisk). (B) Exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm after the endovascular treatment.

After 2 days of intensive care unit stay the patient was transferred to our department, showing progressive recovery of his neurologic status associated with a sharp improvement in the diplopia. The nasal tamponade was removed 4 days after surgery, and no bleeding was observed coming out from the nasal cavity. The patient was dismissed and sent home 1 week later.

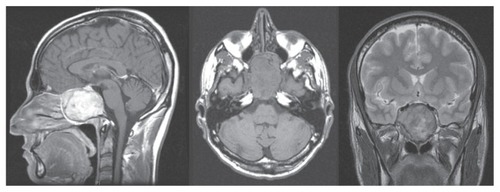

Histologic evaluation of surgical specimens revealed the aspect of a GCT with no infiltration of the surrounding bone. Radiation therapy was not performed. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with angiographic sequences was done regularly 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery in the first year, every 6 months for a further 2 years, then annually.

Six years after surgery the patient was asymptomatic and did not present any relapse of the disease, and there were no signs of microcottonoid infection or aneurysm repermeabilization ().

Discussion

GCTs are uncommon entities comprising 3%–7% of all primary bone neoplasms.Citation20 They commonly originate in the epiphysis of long bones such as the distal femur, proximal tibia, and distal radius, and are rare in the cranium.Citation21 Although they are infrequent, cranial GCTs have the tendency to involve the skull base, particularly the sphenoid and petrous temporal bone.Citation6,Citation7 Although treatment for typical GCT of the long bones is generally well defined, managing lesions located in the skull remains unclear, though a wide surgical excision is generally preferred in order to reduce the risk of local recurrence.Citation8,Citation9 Complete surgical removal of neoplasms originating in the clivus represents a challenge for the neurosurgeon, particularly when facing GCTs that also require the resection of the surrounding apparently healthy bone.Citation22 Access to the clivus has traditionally necessitated extended lateral, posterolateral, and anterior surgical approaches. Lateral transtemporal or far lateral approaches require handling of the cranial nerve, as well as carotid and vertebrobasilar structures, to reach the clivus, thereby increasing the risk of their injury. Anterior approaches allow more direct access to the clivus, representing a preferable route, as they place the pathology at the center of the surgical field while leaving neurovascular structures peripherally. However, the transfacial approach is cosmetically disfiguring, and the sublabial or endonasal microscopic approach provides a narrow corridor that limits the view of the microscope, especially around the corner.Citation23

Recently, advances in the endoscopic instrumentation have led to an increased use of endoscopic EEA to approach the CVJ.Citation11–Citation14,Citation23 Advantages of EEA include the utilization of natural apertures and corridors, improved visualization and magnification by moving the lens and by using a light source closer to the pathology, the possibility to look laterally with angled endoscopes, and the ability to approach the clivus without manipulating critical neurovascular structures, going straight to the tumor’s implant.

In this paper we report a case of GCT treated by an endoscopic EEA in which the close-up vision provided by the endoscope allowed us to completely remove the lesion and adequately drill the surrounding apparently healthy bone. This approach also permitted control of an intraoperative bleed due to an accidental tear of the left ICA. Injury of the ICA during endonasal surgery is a rare complication, but when it happens it can be fatal. Immediate packing or tamponade insertion is necessary to arrest the bleeding, and once the circulation is stabilized the patient should undergo ICA angiography to disclose and treat the ICA injury.Citation15–Citation19 Darkening of the surgical field as a result of blood dirtying the endoscope, as well as difficulties in quickly introducing hemostatic agents, are factors that make intraoperative bleeding control much more difficult in endoscopic endonasal surgery than in other open approaches.Citation24 However, there are some tips and tricks to arrest the blood loss and, at the same time, continue the tumor excision.

In the case described here we found very useful the perfect collaboration between the two surgeons, the careful selection of the most appropriate nostril for endoscope positioning, the large bore suction placement, and the quick “blind” approach to the ICA rupture irrespective of the blood loss. Only once the surgical field was controlled was the site of bleeding addressed and the packing of the ICA tear done with the help of topical hemostatic agents and microcottonoids left adherent to the artery fissuration. This allowed temporary control of the bleeding, giving time for the definitive endovascular treatment, which was performed immediately after endonasal surgery.

Conclusion

Clival GCTs are very rare lesions that can now be completely removed by a minimally invasive, fully endoscopic EEA. The close-up vision provided by the endoscope facilitates complete removal of the tumor and surrounding bone, but at the same time it could be associated with challenging control of bleeding in case of ICA injury. A significant amount of experience, coordination, and teamwork by surgeons as well as some surgical tricks are needed to maintain a surgical view and arrest blood loss.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SiebenrockKAUnniKKRockMGGiant-cell tumour of bone metastasising to the lungs. A long-term follow-upJ Bone Joint Surg Br199880143479460951

- van HoevenKHKelloggKBavariaJEPulmonary metastasis from histologically benign giant cell tumor of bone. Report of a case diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytologyActa Cytol19943834104148191833

- ZorluFSelekUSoylemezogluFOgeKMalignant giant cell tumor of the skull base originating from clivus and sphenoid boneJ Neurooncol200676214915216205965

- WolfeJT3rdScheithauerBWDahlinDCGiant-cell tumor of the sphenoid bone. Review of 10 casesJ Neurosurg19835923223276864300

- WatkinsLDUttleyDArcherDJWilkinsPPlowmanNGiant cell tumors of the sphenoid boneNeurosurgery19923045765811584357

- MotomochiMHandaYMakitaYHashiKGiant cell tumor of the skullSurg Neurol198523125303964973

- RockJPMahmoodACramerHBGiant cell tumor of the skull baseAm J Otol19941522682728172316

- ManasterBJDoyleAJGiant cell tumors of boneRadiol Clin North Am19933122993238446751

- YamamotoMFukushimaTSakamotoSTomonagaMGiant cell tumor of the sphenoid bone: long-term follow-up of two cases after chemotherapySurg Neurol19984955475529586934

- BennettCJJrMarcusRBJrMillionRREnnekingWFRadiation therapy for giant cell tumor of boneInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys19932622993048491687

- AbuzayedBTanrioverNGaziogluNAkarZExtended endoscopic endonasal approach to the clival regionJ Craniofac Surg201021124525120098190

- ArbolayOLGonzálezJGGonzálezRHGálvezYHExtended endoscopic endonasal approach to the skull baseMinim Invasive Neurosurg200952311411819650013

- GladiMIacoangeliMSpecchiaNEndoscopic transnasal odontoid resection to decompress the bulbo-medullary junction: a reliable anterior minimally invasive technique without posterior fusionEur Spine J201221 Suppl 1S55S6022398642

- IacoangeliMDi RienzoAAlvaroLScerratiMFully endoscopic endonasal anterior C1 arch reconstruction as a function preserving surgical option for unstable atlas fracturesActa Neurochir (Wien)2012154101825182622922979

- ValentineRWormaldPJCarotid artery injury after endonasal surgeryOtolaryngol Clin North Am20114451059107921978896

- SolaresCAOngYKCarrauRLPrevention and management of vascular injuries in endoscopic surgery of the sinonasal tract and skull baseOtolaryngol Clin North Am201043481782520599086

- ValentineRWormaldPJControlling the surgical field during a large endoscopic vascular injuryLaryngoscope2011121356256621344434

- ValentineRWormaldPJA vascular catastrophe during endonasal surgery: an endoscopic sheep modelSkull Base201121210911422451811

- ParkYSJungJYAhnJYKimDJKimSHEmergency endovascular stent graft and coil placement for internal carotid artery injury during transsphenoidal surgerySurg Neurol200972674174619604552

- EpsteinNWhelanMReedDAleksicSGiant cell tumor of the skull: a report of two casesNeurosurgery19821122632677121785

- GoldenbergRRCampbellCJBonfiglioMGiant-cell tumor of bone. An analysis of two hundred and eighteen casesJ Bone Joint Surg Am19705246196645479455

- BitohSTakimotoNNakagawaHNambaJSakakiSGohmaTGiant cell tumor of the skullSurg Neurol197893185188635765

- FraserJFNyquistGGMooreNAnandVKSchwartzTHEndoscopic endonasal minimal access approach to the clivus: case series and technical nuancesNeurosurgery2010673 Suppl operativeons150ons15820679934

- KassamASnydermanCHCarrauRLGardnerPMintzAEndoneurosurgical hemostasis techniques: lessons learned from 400 casesNeurosurg Focus2005191E716078821