Abstract

Background

Non-small cell lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States. Patients with late-stage disease (stage 3/4) have five-year survival rates of 2%–15%. Care quality may be measured as time to receiving recommended care and, ultimately, survival. This study examined the association between race and receipt of timely non-small cell lung cancer care and survival among Veterans Affairs health care system patients.

Methods

Data were from the External Peer Review Program, a nationwide Veterans Affairs quality-monitoring program. We included Caucasian or African American patients with pathologically confirmed late-stage non-small cell lung cancer in 2006 and 2007. We examined three quality measures: time from diagnosis to (1) treatment initiation, (2) palliative care or hospice referral, and (3) death. Unadjusted analyses used log-rank and Wilcoxon tests. Adjusted analyses used Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

After controlling for patient and disease characteristics using Cox regression, there were no racial differences in time to initiation of treatment (72 days for African American versus 65 days for Caucasian patients, hazard ratio 1.04, P = 0.80) or palliative care or hospice referral (129 days versus 116 days, hazard ratio 1.10, P = 0.34). However, the adjusted model found longer survival for African American patients than for Caucasian patients (133 days versus 117 days, hazard ratio 0.31, P < 0.01).

Conclusion

For process measures of care quality (eg, time to initiation of treatment and referral to supportive care) the Veterans Affairs health care system provides racially equitable care. The small racial difference in survival time of approximately 2 weeks is not clinically meaningful. Future work should validate this possible trend prospectively, with longer periods of follow-up, in other veteran groups.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death, accounting for 29% of all cancer-related deaths among men.Citation1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is responsible for approximately 85% of lung cancers.Citation2 NSCLC has a dismal prognosis, with 5-year survival rates ranging from 49% for patients with stage 1A of the disease to approximately 1% for those with stage 4.Citation2 Because survival rates are poor, the goal of much therapy for late-stage NSCLC patients is palliative, often focusing on formal referrals to palliative care and/or hospice services. For patients with late-stage disease, recommended treatment ranges from chemotherapy and radiation with or without surgery (stage 3A), to chemotherapy and radiation without surgery or chemotherapy alone (stage 3B), to chemotherapy alone for patients with metastatic disease (stage 4).Citation3,Citation4

There is a clear link between quality of care and patient outcomes. Receipt of timely, stage-appropriate care for NSCLC patients can increase the length of survival.Citation5 Despite the Institute of Medicine prioritizing the receipt of timely treatment as a measure of quality,Citation6 many studies have identified differences in care quality among NSCLC patients of diverse races that may contribute to racial differences in outcomes.Citation7 In fact, there is evidence of racial disparities in care quality measures throughout the NSCLC treatment trajectory. Proper staging is essential for effective treatment planning, yet there are racial differences in receipt of positron emission tomography imaging to accurately stage patients.Citation8 Once a patient has been staged, for those with early-stage NSCLC, timely receipt of surgical resection has a critical impact on survival outcomes. Several studies have shown that African American patients are less likely to receive surgical resection than their Caucasian counterparts.Citation9,Citation10 Racial differences also exist in terms of patient treatment refusal rates,Citation11 and appropriateness and timeliness of care among Medicare beneficiaries.Citation12,Citation13 One study found that relative to Caucasian patients, African American patients were 34% less likely to receive timely surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation for stage 3 NSCLC, and 51% less likely to receive chemotherapy in a timely fashion for stage 4 disease.Citation12

Although the existence of racial disparities in NSCLC is well documented, the cause of these racial differences is complex. Reasons include a cumulative effect of both patient and health system factors. Evidence suggests that when patients receive the right care at the right time, there is little racial difference in survival rates. For example, among patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, there was a 3% absolute difference in survival favoring Caucasian patients over minorities.Citation14 In an analysis of late-stage NSCLC Medicare beneficiaries, the 5-year survival rates for Caucasian and African American patients were 17.7% and 19.6%, respectively. After controlling for socioeconomic status, this difference disappeared entirely.Citation5 Similarly, after controlling for receipt of surgery, differences in survival rates for early-stage NSCLC patients were comparable across racial groups.Citation15 Similar survival rates by race were found among veterans with early-stage disease who received surgery.Citation16,Citation17

The Veterans Health Administration, the largest integrated US health care system, is reputed as an equal-access provider.Citation18 As such, the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system provides an excellent environment in which to study the quality of cancer care among patients with NSCLC. We hypothesized that if patients received equitable and timely care, there would subsequently be similar survival rates by race. Focusing on patients with late-stage NSCLC (stage 3 and 4), we expand upon previous work by examining racial differences in two dimensions of quality of VA NSCLC care: processes of care (time to treatment) and outcomes (survival).

Methods

Data source

The Veterans Health Administration Office of Analytics and Business Intelligence (formerly the Office of Quality and Performance) conducted the External Peer Review Program Lung Cancer Special Study to evaluate the quality of lung cancer care provided in the VA. As described previously,Citation19 patients were identified through the VA Central Cancer Registry.Citation20 Patients were eligible for the External Peer Review Program study if they had been diagnosed with lung cancer between October 1, 2006, and December 31, 2007; had documented pathological confirmation of lung cancer in the electronic medical record; and had survived at least 31 days after diagnosis. Patients were excluded for any of the following reasons: lung cancer diagnosed during autopsy; enrollment in hospice less than 31 days after diagnosis; enrollment in a cancer clinical trial; preexisting or concurrent diagnosis of metastatic cancer (other than lung cancer); documentation of comfort measures only; or life expectancy of 6 months or less. Data were manually abstracted from a national electronic medical record by trained abstractors between February 3, 2010, and August 11, 2010.

Measures

The analytic data set consisted of African American and Caucasian patients with pathologically confirmed late-stage (stage 3 or stage 4) NSCLC. We assessed three dependent variables. We included two process measures of care timeliness: (1) time from diagnosis to initiation of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or admission into palliative care or hospice) and (2) time from diagnosis to referral to palliative care or hospice. The third measure was time from diagnosis to death. Death information was obtained during data abstraction, approximately 2 years from diagnosis. For all measures, time was expressed as the number of days between events.

The primary independent variable of interest was patient race. Because there were relatively few non-African American minority patients in the cohort (N = 56), we restricted our analyses to African American and Caucasian patients; we lacked data on Hispanic ethnicity. Covariates included demographic characteristics (age at diagnosis, marital status, and geographic region) and clinical factors (stage at diagnosis and performance status) previously associated with timeliness of care.Citation21,Citation22 Patients were considered to have poor performance status if the medical record contained documentation of any of the following: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score >2, Karnofsky Performance Status Scale score <60%, or an Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 (ACE-27) score of moderate or severe (2 or 3). Non-African American minority patients, those missing race information, and duplicate records were excluded from the final analytic data set.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate time-to-event curves. The models did not converge when we attempted to control for geographic clustering. We present the racial distribution of key variables (stage at diagnosis, performance stage, and age). To compare differences in unadjusted survival curves between African American and Caucasian patients, we used the log-rank and Wilcoxon tests. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the association between race and time to event after controlling for the previously mentioned covariates. The Efron method was used to handle ties.Citation23,Citation24 Statistical significance was assessed at a conventional alpha level of ≤0.05. Data management and analyses were conducted in Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

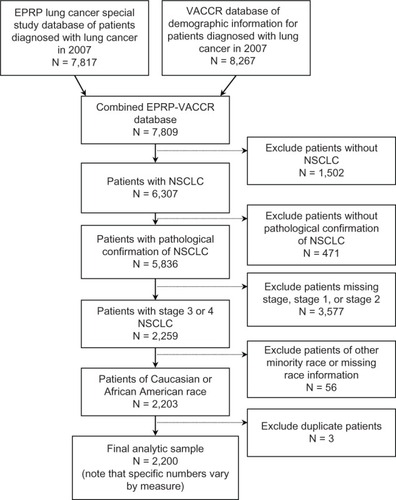

Our final analytic sample consisted of 2,200 patients with NSCLC (). At the time of diagnosis, 83% were Caucasian, 46% were married, 33% were aged 55–64 years, and 47% lived in the South (). The majority of patients (89%) were diagnosed with metastatic disease, and 65% had documentation of poor performance status. Overall, the mean time from diagnosis to initiation of treatment (defined as first date of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or admission to palliative care or hospice; patients may have had multiple treatment modalities) was 66 days, or approximately 2 months. When we examined racial groups separately, the mean times to initiation of treatment were similar for Caucasian and African American patients (65 days versus 72 days, respectively). The mean time between diagnosis and referral to palliative care or hospice was 118 days, with Caucasian patients being referred an average of 13 days earlier (116 days versus 129 days). The mean time from diagnosis to death was approximately 120 days, or 4 months, with Caucasian patients dying 16 days sooner than African American patients (117 days versus 133 days; ). Patients were similar by race with regard to stage at diagnosis (P = 0.48) and performance status (P = 0.85).

Table 1 Description of NSCLC patient cohort and key variables

Figure 1 Lung cancer cohort assembly.

Abbreviations: EPRP, External Peer Review Program; N, number; VACCR, Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

Approximately 70% of patients received treatment for their NSCLC. Among patients who received treatment, the mean time to initiation of treatment was 66 days. In unadjusted analysis, there were no racial differences in time to initiation of treatment (Wilcoxon P = 0.94; log-rank P = 0.99). After adjustment, there remained no association between time to initiation of treatment and race (hazard ratio [HR] 1.04, P = 0.80), marital status (HR 1.00, P = 0.98), age at diagnosis, region, stage at diagnosis (HR 0.87, P = 0.47), or performance status (HR 0.81, P = 0.09; ).

Table 2 Cox proportional hazard model regression results

More than half (54%, N = 1,178) of all patients were referred to palliative care or hospice, with referral occurring approximately 118 days after diagnosis. In unadjusted analyses, there were no racial differences in time to palliative care or hospice referral (Wilcoxon P = 0.29; log-rank P = 0.57). The lack of association by race remained in the adjusted Cox models (HR 1.10, P = 0.34; ). Compared with patients with stage 4 disease, those with stage 3 had approximately a 36% higher hazard of referral (HR 1.37, P < 0.01) to palliative care or hospice. Compared with patients with documentation of poor performance status, healthier patients had approximately a 20% reduced hazard of referral (HR 0.81, P = 0.01) to palliative care or hospice. There were no other associations between referral and patients’ sociodemographic characteristics.

At the time of data collection, approximately 78% individuals of the sample population were deceased, with a mean time from diagnosis to death of approximately 120 days, or 4 months. In unadjusted analysis, Caucasians died sooner than African Americans (Wilcoxon P = 0.00; log-rank P < 0.01). This finding remained after adjustment for covariates (HR 0.31, P < 0.01). Being married (HR 0.89, P = 0.02) and being less than 55 years of age (HR 0.76, P = 0.01) were protective against death compared with being unmarried or >75 years old at diagnosis. Geographic region was not associated with time to death. Compared with those with metastatic disease, patients with stage 3 disease had approximately a 50% reduced hazard of death (HR 0.53, P < 0.01). Poor performance status was also associated with time to death (HR 0.80, P < 0.01; ).

Discussion

We examined two dimensions of quality of VA NSCLC care: processes of care (time to treatment) and outcomes (survival). Among patients with late-stage NSCLC, we observed no racial differences in processes of care. In fact, there were no significant associations between time from diagnosis to initiation of treatment and any patient-level characteristics. This supports the VA’s reputation as an equal-access system. The mean time to first treatment that we observed, approximately 66 days, is consistent with a previous VA study of advanced NSCLC.Citation25 Although some have argued that a 2-month delay may negatively affect patients’ emotional states,Citation26 there are no formalized guidelines regarding timeliness of treatment for NSCLC. Thus, these findings suggest that the VA provides equitable and timely access to critical health services for patients with late-stage NSCLC.

Palliative care is critical for effective management of pain and other distressing symptoms and is often provided in conjunction with other therapies. Recent literature has suggested that enrollment in hospice does not compromise the length of survival for patients after advanced lung cancer diagnosis,Citation27 and may in fact extend life by 2 months.Citation28 As a result, some have suggested that patients be referred to palliative care within 4 to 6 weeks of diagnosis.Citation29 In the absence of timeliness standards, it is clear that the VA is committed to referring all patients in a common timeframe. We found that more than half of patients with advanced NSCLC were referred to palliative care or hospice services, with no significant racial differences. Moreover, these data suggest that patients seem to be referred appropriately on the basis of their health status, because patients with metastatic disease or poor performance status were sent to palliative care and/or hospice more quickly.

We also examined survival rates up to 2 years from diagnosis. As anticipated, we found that metastatic disease, poor performance status, and increased age at diagnosis were associated with shorter survival times. Marriage had a protective effect, which has also been demonstrated in prior studies.Citation30 In these data, African American patients survived a mean of 16 days longer than Caucasian patients, even after we controlled for prespecified covariates. Although racial differences in survival time have been documented in nonfederal health care systems, our finding is consistent with several studies that suggested that once equal access to care has been obtained, survival rates are similar for patients of diverse races.Citation22,Citation31,Citation32

Our study has several limitations. First, our analysis was limited to care received in the VA. Some patients receiving care in the VA health care system may also receive a portion of their cancer care in the private sector. Analysis was also limited to patients of African American and Caucasian race without regard to Hispanic ethnicity. Geographic regions were defined based on landmass, not distribution of this sample of VA patients. Future research should endeavor to include information from multiple data sources on a more diverse patient cohort. We obtained death information 2 years after diagnosis; however, this seems reasonable, because 78% of our sample died within this timeframe. We also looked for racial differences in right-censoring of the data. At the time of data capture, approximately 81% of African Americans and 88% of Caucasian patients were deceased (P < 0.01). Future studies should endeavor to include longer-term follow-up data to avoid potential censoring bias.

Our findings provided important insights on the quality and timeliness of VA NSCLC care. We assessed key process and outcome measures of care quality and observed no evidence of clinically meaningful racial differences in timeliness of NSCLC care provided by the VA health care system. To validate these findings, future studies that follow patients longitudinally should be conducted. These results may reflect the VA’s history as an equal-access system,Citation18,Citation33,Citation34 and its established commitment to ongoing quality monitoring and improvement.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Durham VA Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care (HSR&D) Center of Excellence. Development of the data set was funded by funds transferred from the Veterans Health Administration Office of Quality and Performance to the HSR&D Center of Excellence at the Durham VA Medical Center. Dr Zullig was funded by the National Cancer Institute (5R25CA116339). Dr Weinberger is a VA HSR&D Senior Research Career Scientist (RCS 91-408). The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SiegelRNaishadhamDJemalACancer statistics, 2012CA Cancer J Clin2012621102922237781

- American Cancer Society [homepage on the Internet]Non-small cell lung cancerAtlanta, GAAmerican Cancer Society2013 Available from: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/lungcancer-non-smallcell/Accessed July 11, 2013

- CooperGSVirnigBKlabundeCNSchusslerNFreemanJWarrenJLUse of SEER-Medicare data for measuring cancer surgeryMed Care200240Suppl 8IV-4348

- PfisterDGJohnsonDHAzzoliCGAmerican Society of Clinical OncologyAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003J Clin Oncol200422233035314691125

- HardyDXiaRLiuCCCormierJNNurgalievaZDuXLRacial disparities and survival for nonsmall-cell lung cancer in a large cohort of black and white elderly patientsCancer2009115304807481819626650

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of MedicineCrossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st CenturyWashington, DCThe National Academies Press2001

- OlssonJKSchultzEMGouldMKTimeliness of care in patients with lung cancer: a systematic reviewThorax200964974975619717709

- GouldMKSchultzEMWagnerTHDisparities in lung cancer staging with positron emission tomography in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) studyJ Thorac Oncol20116587588321572580

- MargolisMLChristieJDSilvestriGAKaiserLSantiagoSHansen-FlaschenJRacial differences pertaining to a belief about lung cancer surgery: results of a multicenter surveyAnn Intern Med2003139755856314530226

- FarjahFWoodDEYanezND3rdRacial disparities among patients with lung cancer who were recommended operative therapyArch Surg20091441141819153319

- LandrumMBKeatingNLLamontEBBozemanSRMcNeilBJReasons for underuse of recommended therapies for colorectal and lung cancer in the Veterans Health AdministrationCancer2012118133345335522072536

- ShugarmanLRMackKSorberoMERace and sex differences in the receipt of timely and appropriate lung cancer treatmentMed Care200947777478119536007

- LandrumMBKeatingNLLamontEBSurvival of older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus fee-for-service MedicareJ Clin Oncol201230101072107922393093

- MorrisAMRhoadsKFStainSCBirkmeyerJDUnderstanding racial disparities in cancer treatment and outcomesJ Am Coll Surg2010211110511320610256

- BachPBCramerLDWarrenJLBeggCBRacial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancerN Engl J Med1999341161198120510519898

- JahanzebMVirgoKMcKirganLJohnsonFEvaluation of outcome by race in early-stage non-small cell lung cancerOncol Rep19974118318621590038

- WilliamsCDProvenzaleDStechuchakKMKelleyMJImpact of race on early-stage lung cancer treatment and outcomeFed Pract2012

- KizerKWDudleyRAExtreme makeover: transformation of the veterans health care systemAnnu Rev Public Health20093031333919296778

- WilliamsCDStechuchakKMZulligLLProvenzaleDKelleyMJInfluence of comorbidity on racial differences in receipt of surgery among US veterans with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol201331447548123269988

- ZulligLLJacksonGLDornRACancer incidence among patients of the US Veterans Affairs Health Care SystemMil Med2012177669370122730846

- PaganoEFilippiniCDi CuonzoDFactors affecting pattern of care and survival in a population-based cohort of non-small-cell lung cancer incident casesCancer Epidemiol201034448348920444663

- ZhengLEnewoldLZahmSHLung cancer survival among black and white patients in an equal access health systemCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev201221101841184722899731

- ClevesMGouldWGutierrezRGMarchenkoYVAn Introduction to Survival Analysis Using Stata3rd edCollege Station, TXStata Press2010

- KleinbaumDGSurvival Analysis: A Self-Learning TextNew York, NYSpringer-Verlag Inc1996

- SchultzEMPowellAAMcMillanAHospital characteristics associated with timeliness of care in veterans with lung cancerAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179759560018948424

- GouldMKDelays in lung cancer care: time to improveJ Thorac Oncol20094111303130419861901

- SaitoAMLandrumMBNevilleBAAvanianJZWeeksJCEarleCCHospice care and survival among elderly patients with lung cancerJ Palliat Med201114892993921767153

- TemelJSGreerJAMuzikanskyAEarly palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancerN Engl J Med2010363873374220818875

- von GuntenCFLutzSFerrisFDWhy oncologists should refer patients earlier for hospice careOncology (Williston Park)20112513127812801282128522272498

- SiddiquiFBaeKLangerCJThe influence of gender, race, and marital status on survival in lung cancer patients: analysis of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trialsJ Thorac Oncol20105563163920432520

- BradleyCJGivenCWRobertsCDisparities in cancer diagnosis and survivalCancer200191117818811148575

- AkerleyWL3rdMoritzTERyanLSHendersonWGZacharskiLRRacial comparison of outcomes of male Department of Veterans Affairs patients with lung and colon cancerArch Intern Med199315314168116888333805

- RobinsonCNBalentineCJMarshallCLEthnic disparities are reduced in VA colon cancer patientsAm J Surg2010200563663921056144

- PerlinJBKolodnerRMRoswellRHThe Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered careAm J Manag Care20041011 Pt 282883615609736