Abstract

Cutaneous T cell lymphomas (CTCL) clinically and biologically represent a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas, with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome being the most common subtypes. Over the last decade, new immunological and molecular pathways have been identified that not only influence CTCL phenotype and growth, but also provide targets for therapies and prognostication. This review will focus on recent advances in the development of therapeutic agents, including bortezomib, the histone deacetylase inhibitors (vorinostat and romidepsin), and pralatrexate in CTCL.

Introduction

Cutaneous T cell lymphomas (CTCL) represent a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas characterized by an initial infiltration of the skin with clonally-derived malignant T lymphocytes of the CD4+ CD45RO+ phenotype that generally lack normal T cell markers, such as CD7 and CD26.Citation1 The diversity of clinical and pathologic manifestations among subsets of CTCL has led to much controversy over its diagnosis and classification and to the establishment of consensus guidelines by a joint effort of the World Health Organization and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (WHO-EORTC) in 2005.Citation2

The two most common types of CTCL are mycosis fungoides (50%–72%), which is generally indolent in behavior, and Sézary syndrome (1%–3%), an aggressive leukemic form of the disease ().Citation2–Citation5 Other types include primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma, and the group of primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphomas that includes the provisional entities of cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T cell lymphoma, cutaneous γ/δ T cell lymphoma, and cutaneous CD4+ small/medium-sized pleomorphic T cell lymphoma.Citation4,Citation6

Table 1 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer consensus classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas with relative frequency and 5-year survival

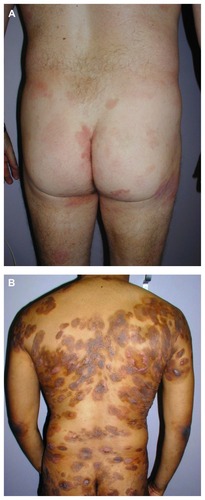

Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome together comprise 54% of all CTCL.Citation2 The annual incidence of CTCL in the United States has increased from 2.8 per million (1973–1977) to 9.6 per million (1998–2002) according to data from Criscione and Weinstock. Citation5 Median age at presentation is between 50 and 70 years,Citation5,Citation7,Citation8 although pediatric and young adult cases do occur.Citation9,Citation10 Mycosis fungoides classically presents with an indolent course and slow progression over years or sometimes decades. The disease may evolve from patches to infiltrated plaques and eventually to tumors (). However, about 30% of patients present with skin tumors (T3) or erythroderma (T4) at initial presentation. Citation8 Sézary syndrome is a much more aggressive disease. Patients with Sézary syndrome present with erythroderma, circulating malignant T cells (Sézary cells), and severe disabling pruritus with or without associated lymphadenopathy (). The TNMB (tumor, node, metastasis, blood) classification for clinical staging is used according to the Mycosis Fungoides Cooperative Group staging systemCitation11 established in 1979 by Bunn and Lamberg, which was revised by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) staging proposal in 2007.Citation12 Advanced clinical stages range from IIB (skin tumors) to IVB (visceral disease).

Figure 1 Patients with mycosis fungoides presenting with limited (A) patches/plaques typically involving the buttocks, and with disseminated (B) patches/plaques and tumors.

Figure 2 Patient with Sézary syndrome presenting clinically with generalized erythroderma and thickening (lichenification) of the skin.

While the overall survival rate of patients with mycosis fungoides is 68% at 5 years and 17% at 30 years, the specific survival of patients ranges widely, depending on T classification and stage at initial presentation.Citation8 The largest study, consisting of 525 patients, showed an overall survival of 97% in patients with T1 (less than 10% body surface involvement) at 5 years, compared with 40% and 41% in T3 and T4 disease, respectively.Citation8 Other studies have shown that elevated lactate dehydrogenase, large-cell transformation, and folliculotropic mycosis fungoides are associated with a worse prognosis.Citation13,Citation14 Patients with Sézary syndrome have an estimated 5-year survival of 24%.Citation4,Citation8 Recent analyses of outcomes in patients with mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome using the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma/EORTC revised staging proposal established that the presence of a T cell clone in blood (identical to the cutaneous T cell clone) in the absence of morphologic evidence of blood involvement (B0b) was also associated with a significantly worse overall survival and disease-specific survival compared with those patients with no peripheral blood T cell clone (B0a).Citation12,Citation13

Research on new therapies for CTCL is largely centered on defining novel targets for therapy. The International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas, the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the EORTC have developed consensus guidelines to facilitate collaboration in clinical trials.Citation15 These proposed guidelines consist of: recommendations for standardizing general protocol design; a scoring system for assessing tumor burden in skin, lymph nodes, blood, and viscera; definition of response in skin, nodes, blood, and viscera; a composite global response score; and a definition of end points. Although these guidelines were generated by consensus panels, they have not been prospectively or retrospectively validated by analysis of large patient cohorts. This review focuses on current and new discoveries that have provided targets for therapy in patients with mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome. We will briefly give an overview of recent molecular discoveries and dysregulated signaling pathways, followed by a presentation of current and novel topical, biological, and chemotherapy treatments for CTCL patients.

Immunologic and molecular findings in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

Immunologic mechanisms of pathogenesis

Most malignant T cells in CTCL are clonally derived from CD4+ T helper memory cells.Citation16 In the early stages of mycosis fungoides, the T cell infiltrate consists of both malignant CD4+ and reactive CD8+ T cells, with a dominance of Th1 cytokines, such as interferon-gamma (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-12, and IL-2.Citation17 In the later stages, there is a gradual increase in malignant CD4+ cells, a decrease in nonmalignant CD8+ cells, and a shift to Th2 cytokine dominance (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13).Citation18 These changes correlate with disease progression, host immunosuppression, and susceptibility to infection.Citation19 Biologic immune modifiers, such as IFN-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12, are therapeutically effective in CTCL by stimulating Th1 cytokines and boosting host immune responses. The recently discovered Th17 lineage of CD4+ T cells functions in host protection against extra-cellular bacteria and fungi.Citation20 Th17-derived cytokines (IL-17, IL-21, and IL-22) have been implicated in autoimmunity.Citation21 Recently, the Th1/Th2 paradigm of CTCL has been revisited, including a role for a IL-17-producing T cell (Th17) population in cutaneous lesions of patients with mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome.Citation22 Interestingly, IL-17 was not measurable in serum samples of patients with mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome, suggesting that this cytokine may only play a role in cutaneous lesions. In another study, IL-17 protein was found to be mediated by IL-2/IL-15 through the Jak3/STAT3 pathway.Citation23 Other immune regulatory molecules found to be overexpressed in CTCL include IL-15, IL-16, and IL-21, and programmed death-1 (PD-1).Citation24–Citation27

Controversial results have been found for PD-1 expression. Increased PD-1 expression has been shown on circulating CD4+ cells in patients with Sézary syndrome when compared with patients with mycosis fungoides, which could imply a role for an increase in PD-1 expression in the progression of tumors.Citation26 However, recent data showed increased PD-1 in pseudolymphoma and cutaneous CD4+ small/medium-sized pleomorphic T cell lymphoma.Citation28 Further research is needed in this area to determine whether the increase in PD-1 expression protects tumor cells from elimination, or if the increased PD-1 expression is a response of immunocompetent cells that are simply chronically stimulated by tumor antigens.

Chemokines and chemokine receptors in CTCL have been reviewed by others.Citation29,Citation30 They mediate not only trafficking of malignant T cells into the skin, but also their survival, possibly due to activation of prosurvival pathways. Chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4) is not only necessary for skin-homing of normal CD4+ T lymphocytes, but also for malignant CTCL cells.Citation31,Citation32 Both CCR4 and CCR10 have been shown to be highly expressed in CTCL skin lesionsCitation33 and in the peripheral blood cells of patients with mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome.Citation34,Citation35 While CCL17, a CCR4 ligand expressed on epidermal keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and dendritic cells, facilitates extravasation and migration of CTCL cells into the skin and epidermis, CCL27, a CCR10 ligand expressed on keratinocytes, has been implicated in both skin and nodal homing of CTCL cells. Anti-CCR4 is currently being evaluated in clinical trials including CTCL patients.

Naturally occur ring regulatory T cells (Tregs, CD4+ CD25+ FOXP3+ phenotype) suppress the activity of other immune cells and thus maintain immunological tolerance. Tregs appear to be dysregulated in CTCL.Citation36 Early cutaneous lesions in patients with mycosis fungoides contain numerous FOXP3+-infiltrating Tregs that decrease in number in advanced lesions. The high frequency of FOXP3+-infiltrating Tregs may suppress tumor proliferation and have been correlated with improved survival.Citation36 Patients with Sézary syndrome have very low levels of Tregs but high levels of malignant T cells expressing a Treg phenotype (FOXP3+ CD25−). These malignant FOXP3 + Tregs express CTLA-4, IL-10, and transforming growth factor-β, which suppress immunity and diminish the antitumor response.Citation19

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA-4) is a coinhibitory molecule expressed on T cells that inhibits T cell activation and proliferationCitation37 and confers resistance against activation-induced cell death.Citation38 Tregs also constitutively express CTLA-4, which is necessary for their functioning to maintain peripheral tolerance and to prevent autoimmunity.Citation39,Citation40 High CTLA-4 expression was found in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with mycosis fungoides, and higher expression levels correlated with increased tumor burden. Th1-derived cytokines, such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, upregulate expression of CTLA-4.Citation41 Whether increased CTLA-4 expression relates to Treg-like properties that CTCL cells acquire during disease progression is not clear; further research is needed to prove this concept. Anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) is an important immunotherapeutic strategy in melanoma; the association of dysregulated CTLA-4 in CTCL suggests a potential therapeutic target in this disease.

Epigenetic mechanisms of pathogenesis

DNA methylation of CpG islands in promoter regions is an epigenetic mechanism of gene expression that tightens chromatin around nucleosomes and interferes with binding of transcription factors.Citation42 This has been shown to downregulate expression of tumor suppressor genes, leading to carcinogenesis in several tumor types.Citation43 In CTCL, promoter hypermethylation leads to dysregulation of the cell cycle (p15, p16, p73), apoptosis (TMS1, p73), DNA repair (MGMT), chromosomal instability (CHFR), and microsatellite instability (MLH1) genes and proteins.Citation44–Citation48 Promoter hypermethylation of p15, p16, and MLH1 was found in both early and advanced stages of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, suggesting that early epigenetic alterations were responsible for the inactivation of these genes.Citation46–Citation48

When genes are hypermethylated and silenced, the histones are in a deacetylated state.Citation42 Acetylation of histones in nucleosomes alters conformation of chromatin. Histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups, leading to compaction of chromatin and repression of transcription.Citation49 In addition to their action on histones, HDACs also regulate various transcription factors, such as the p53 tumor suppressor and E2F oncogene.Citation49 HDACs were initially developed to restore tumor suppressor and cell regulatory genes by inducing histone hyperacetylation.Citation50

Apoptotic mechanisms of pathogenesis

Defective regulation of apoptosis is a central feature of the pathology of several lymphoma types, including mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Apoptosis can be triggered by death receptors that belong to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family or by aberrations in expression of the B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family. Malignant CD4+ T cells from cutaneous lesions and peripheral blood samples in mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome have decreased and/or defective Fas expression, and decreased Fas expression has been correlated with more aggressive disease as well as resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis.Citation51–Citation54 Thus, downregulation of Fas may be one way in which CTCL cells become resistant to chemotherapy. Downregulation of Fas in CTCL occurs through multiple mechanisms, ie, mutations in the Fas gene,Citation52 production of nonfunctioning splice variants,Citation55 and promoter hypermethylation.Citation56 In this context, malignant T cells in CTCL may acquire resistance to FasL signaling through increased expression of cFLIP, an intracellular apoptosis inhibitor.Citation51

The expression of other antiapoptotic molecules, such as p53 and Bcl-2 family members, has been studied in CTCL. In one in vitro study, p53 mutations were identified in tumor stage mycosis fungoides, but not in patch/plaque mycosis fungoides.Citation57 In another study, there was no correlation between clinical stage and p53 mutations.Citation58 One pathway being targeted for antineoplastic therapy is the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-2-like family of proteins. T cells generally express Bcl-2 that inhibits apoptosis and is widely and stably expressed in all stages of mycosis fungoides.Citation59 Data suggested that inhibition of Stat3 signaling in CTCL cells through the Jak kinase inhibitor, Ag490, induced apoptosis through decreased expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 and increased expression of the proapoptotic Bax protein.Citation60 Surprisingly, other investigators found late-stage disease and shorter survival time were correlated with decreased Bcl-2 expression.Citation58 However, information about quantification of Bcl-2 protein expression was not provided. It also remains unclear whether the low expression is related to alterations of genes, such as p53, that impact Bcl-2 expression.

Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) is a member of the PLK family of serine/threonine kinases crucial to the cell division cycle, which has been postulated to induce oncogenesis in multiple solid and hematologic malignancies.Citation61–Citation64 Increased expression has been found with progression and metastasis. Plk1 expression is elevated in CTCL, and in particular is found in tumor-stage and in folliculotropic and erythrodermic types of CTCL.Citation65,Citation66 In vitro studies with both small molecule inhibition and shRNA-mediated knockdown of Plk1 resulted in decreased cell growth, decreased cell viability, G2/M arrest, and apoptosis in CTCL cells.Citation66 In addition, CTCL cell lines with p53Citation35 and k-rasCitation36 mutations appear to be sensitive to Plk inhibition and may serve as biomarkers for patient selection. Currently there are a number of Plk inhibitors in preclinical development,Citation67 and results have been reported from Phase I studies for four of them (BI 2536,Citation68 GSK 461364,Citation69 ON-01910,Citation70 and HMN-214Citation71). Although these inhibitors were studied mainly in solid tumors, with modest responses reported and prolongation of stable disease at best, they have yet to be studied in CTCL. Plk1 could serve as a potential target in advanced stages, when its expression is generally high.

The existence of multiple mechanisms of oncogenesis in CTCL and the variety of mechanistic combinations in individual patients may perhaps require more individualized therapy. A recent report of cotreatment with the HDAC inhibitor, panobinostat, and the Bcl-2 antagonist, ABT-737, found synergistic induction of apoptosis in CTCL cells.Citation72

Molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis

Genome-wide analysis of chromosomal alterations is increasingly used as a research tool in the search for novel agents to treat CTCL.Citation73–Citation75 Improvements in microarray technology and computational analysis of genomic data have led to discoveries of underlying chromosomal mutations in tumor suppressor and oncogenes involved in CTCL.Citation73–Citation75 Chromosomal regions with significant gains include 8q (including the MYC oncogene), 17q, and 10p13 (including GATA3, a transcription factor which promotes Th2 cytokine production).Citation74 Additionally, a recent study suggested that amplifications on 4q12 (including KIT), 7p11.2 (including EGFR), and 17q25.1 may be highly associated with patients refractory to treatment.Citation74 Specific oncogenes have been examined for defining new prognostic factors in CTCL. Deletions have been found on chromosomes 17p (including TP53), 10p, and 10q (including PTEN and FAS), 13q including RB1, and 9p21.3 (including CDKN2A).Citation74

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression. miRNAs have been shown to become dysregulated in cancer, providing the basis for development of miRNA-targeted cancer therapies.Citation76 A microarray screen found that five miRNAs (miR-203, miR-205, miR-326, miR-663b, and miR-711) distinguish CTCL from benign skin diseases, with an accuracy of greater than 90%.Citation77 In tumor-stage mycosis fungoides, miR-93, miR-92A, and miR-155 were upregulated in comparison with benign inflammatory skin diseases.Citation78 In Sézary syndrome, most miRNAs were downregulated, but miR-21, miR-486, and miR-214 are upregulated and are involved in apoptotic resistance.Citation79 miR-21 has been shown to mediate oncogenic signaling by STAT3 and may be a possible therapeutic target for Sézary syndrome.Citation27,Citation80

Current and emerging therapies for early-stage disease

Patients with early-stage mycosis fungoides often present with disease limited to the skin without systemic involvement; in these patients, a durable response can be achieved in approximately 60%–80% of cases with skin-directed therapies. Patients with early-stage disease may be effectively treated with topical agents, because previous data have demonstrated that there is no benefit to aggressive use of systemic chemotherapy.Citation81 Existing therapeutic approaches include phototherapy with psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA), narrowband ultraviolet B (NB-UVB), total electron beam irradiation (TSEBT), and topical formulations of corticosteroids, nitrogen mustard, and retinoids/rexinoids. Success rates with PUVA are 90% for stage IA, 76% for stage IB, 78% for stage IIA, 59% for stage IIB%, and 61% for stage III CTCL.Citation82–Citation84 The most common reported acute side effects were erythema, pruritus, and nausea. Long-term exposure was associated with an increased risk for developing chronic photodamage and nonmelanoma skin cancer.Citation84

Recent consensus from the EORTC indicates that patients with patches and thin plaques should be given NB-UVB treatment, whereas PUVA should be reserved for patients with folliculotropic mycosis fungoides, failure of NB-UVB treatment, or dark complexion, due to carcinogenic effects, as well as a paucity of available treatment centers.Citation85 Early-stage refractory patients may benefit from combination therapies, such as NB-UVB or PUVA with low-dose systemic oral bexarotene, acitretin, or IFN-α.Citation86 High-potency topical corticosteroids have also been shown to have an overall response rate of >90% in patch-stage mycosis fungoides, with some side effects of irritant dermatitis and cutaneous atrophy.Citation87,Citation88 Topical nitrogen mustard has a complete response rate of 76%–80% for stage IA and 35%–68% complete response rate for stage IB disease.Citation89 Common side effects are contact hypersensitivity reactions. Bexarotene gel is a retinoid X receptor agonist and is approved for early-stage mycosis fungoides.Citation90 In clinical trials, it has been shown to have an overall response rate (ORR) of 54% and a complete response rate of 10% in patients with stages IA–IIA mycosis fungoides. It commonly causes skin irritation. Tazarotene gel, a retinoic acid receptor agonist, is another topical retinoid approved for use in psoriasis and acne, and has been shown to improve skin lesions in refractory mycosis fungoides and may be useful as an adjuvant topical treatment.Citation91 TSEBT is a procedure that involves administering ionizing radiation to the entire skin surface.Citation83 TSEBT has been shown to be an effective therapy for palliation of the cutaneous symptoms of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome.Citation83 Because the electron beam radiation in TSEBT has greater energy and depth of penetration than other skin-directed therapies, it may be an option for treatment of stage T2 or T3 mycosis fungoides.Citation83 Options may be limited for Caucasian patients, and TSEBT toxicity can be cosmetically disfiguring. A recent study from Stanford followed 180 patients with T2 or T3 mycosis fungoides on TSEBT treatment and found that all patients had over 50% improvement in skin involvement, with 63% achieving a complete clinical response (75% for T2 patients and 47% for T3 patients) with a median duration of response of 29 months in T2 patients and 9 months in T3 patients.Citation83 These results confirm the work of previous studies showing that a conventional dose (30–36 Gy) of TSEBT is significantly more efficacious in T2 than in T3 mycosis fungoides.

Newer topical and investigational therapies include Toll- like receptor (TLR) agonists, gene therapy agents, 308 nm excimer laser, and photodynamic therapy. Imiquimod (Aldara® cream 5%), a TLR-7 agonist that induces tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IFN-α, and IFN-γ expression, has been shown to cause clinical and histologic clearance of limited skin lesions in a small number of patients.Citation92–Citation95 TG-1042 is a replication-deficient adenovirus vector expressing IFN-γ that has been shown to induce a Th1 response when injected intralesionally.Citation96 A recent Phase II trial of repeated intralesional TG-1042 injections had a local response rate of 46% in CTCL patients and minimal adverse effects, including injection site reactions, lymphopenia, fever, and chills.Citation97 Further, 308 nm excimer laser has been shown to be an effective and well tolerated therapy for limited-stage mycosis fungoides in several small studies. It may be preferred over NB-UVB due to its greater precision in localizing treatment to small skin lesions, leading to decreased phototoxicity and better patient compliance. However, cost and availability are limitations.Citation98–Citation103 Photodynamic therapy utilizes a photosensitizer, light, and oxygen to induce reactive oxygen species. Two photosensitizers, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA; Levulan®) and methyl aminolevulinate hydrochloride have been used in CTCL. Treatment with ALA had efficacy in localized CTCL but not in tumor-stage CTCL, possibly due to insufficient penetration of 5-ALA and/or light.Citation104,Citation105 Common adverse effects of ALA include pain that occurs during light exposure, erythema, edema, and postinflammatory pigment changes.Citation106 Due to the limited efficacy and side effect profile of ALA, other photosensitizers have been recently tested in CTCL. Methyl aminolevulinate hydrochloride, the methyl ester derivative of ALA, with greater lipophilia resulting in increased penetration and less pain, induced a complete response in six of seven cases of resistant unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides, with no recurrence during follow-up periods from 12 to 34 months.Citation107–Citation109 Silicon phthalocyanine Pc 4 has been shown to induce apoptosis in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with Sézary syndrome.Citation110 Hypericin ointment, another photosensitizer, induced a response in a Phase II trial of 12 patients, with adverse effects of burning, itching, erythema, and pruritus at the site of application.Citation111

Current and emerging therapies for advanced-stage disease

Biological therapies

Patients with advanced disease (stage IIB–IVB) may have disseminated disease into lymph nodes and other organs, and may exhibit multiple immune derangements necessitating systemic therapy. While no regimen has been proven to prolong survival in the advanced stages, immunomodulatory regimens should be used initially to reduce the need for cytotoxic therapies. Decreased cell-mediated immunity with a dominant Th2 cytokine profile is observed in advanced stages of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Bexarotene, immunomodulatory cytokines such as IFN-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12, and extracorporeal photopheresis enhance the host antitumor response by either maintaining Th1 skewing or inhibition of Th2 cytokine production.

Extracorporeal photopheresis, approved in 1988 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the palliative treatment of patients with CTCL, is best suited to patients with Sézary syndrome, within 2 years of disease onset, near normal counts of CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells, and modest tumor burden.Citation112 Overall response rates have ranged from 31% to 73% when CTCL patients are treated with extracorporeal photopheresis as monotherapy, but have been shown to have greater efficacy in various combinations with IFN-α, IFN-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and bexarotene, due to enhancement of antitumor immunity.Citation113,Citation114 The novel continuous flow separation system (Therakos™ Cellex™) has been developed based on the current Uvar® XTS™ photopheresis device and is designed to reduce treatment times and extracorporeal volumes.

IFN-α is one of the most widely used first-line treatments and probably the most effective single agent in the treatment of CTCL. It has shown a wide range of biologic effects, including antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunomodulatory actions. The exact mechanism by which interferons exert their antitumor effects remains unknown. Th1 cytokines support cytotoxic T cell-mediated immunity and it has been speculated that IFN-α maintains or enhances a Th1 cell population balance for an effective cell-mediated response to malignant T lymphocytes. A response rate of 73% in stage IA–IIA and 60% response in stage IIB–IVA disease has been seen with IFN-α monotherapy.Citation115 When IFN-α is used in combination with PUVA, both overall response rates and response duration show improvement, with studies demonstrating overall response and complete response rates of 98% and 84%.Citation116,Citation117 While the optimal dose and duration has not been established yet in CTCL, current experience suggests that therapy should be given at a starting dose of 1–3 million units five times weekly, with gradual escalation to 6–9 million units daily or as tolerated.

Denileukin diftitox

Denileukin diftitox (Ontak®) is an IL-2 diphtheria toxin fusion protein targeted against malignant T cells expressing CD25, the high-affinity IL-2 receptor. Denileukin diftitox was approved by the FDA in 1999 for the treatment of patients with CTCL refractory to standard treatment options. In general, response rates in patients with relapsed and refractory mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome range from 30% to 37%.Citation118 A recent randomized Phase III trial in CD25 + CTCL demonstrated an ORR of 44% for patients treated with denileukin diftitox versus 15.9% for patients on placebo. CTCL patients were randomly assigned to denileukin diftitox 9 μg/kg/day (n = 45), denileukin diftitox 18 μg/kg/day (n = 55), or placebo infusions (n = 44). In addition, patients treated with both doses of denileukin diftitox had a significantly longer progression-free survival than patients on placebo.Citation119 The incidence of grade 3 and 4 capillary leak syndrome was seen in 2–3 patients (3.6%) at doses of 18 μg/kg/day. A key remaining question of whether response to denileukin diftitox depends on expression of CD25 was explored in a retrospective study of complete responders in previous Phase II and Phase III trials. This study found no difference in response between patients with CD25-positive and CD25-negative disease.Citation120

Histone deacetylase inhibitors

HDAC inhibitors were initially developed to modulate chromatin condensation by acetylation of histones affecting gene expression. More recently, their effects on post-translational modification of many intracellular proteins have been recognized.Citation121 Vorinostat (sub-eroylanilide hydroxamic acid; Zolinza®), an orally administered HADC inhibitor, was approved by the FDA in 2006 for the treatment of relapsed/refractory CTCL. A Phase IIB trial was conducted in 74 patients with stage IB–IVA CTCL, including 82% with ≥stage IIB disease. ORR was 29.7%. Oral vorinostat was administered at 400 mg daily. The median time to response was 2 months and median duration of response was not reached, but was estimated to be longer than 6.1 months. In addition, 43.4% of patients with severe pruritus experienced relief. The most common adverse effects included diarrhea, fatigue, and nausea, but most were of grade 2 or lower. Significant grade 3 side effects included pulmonary embolism (5%) and thrombocytopenia (5%). In this study, QTc interval prolongation was observed in three patients with no reported clinical sequelae, none of which were grade 3. There were no cases of infection.Citation122 Another Phase II trial of vorinostat conducted in 33 patients with advanced or refractory CTCL at multiple doses demonstrated an ORR of 24% with a median time to response of 3 months and a median duration of response of 3.7 months. Forty-five percent of patients experienced relief of pruritus.Citation123 In addition, analysis of lesion biopsies in responding patients demonstrated a shift in localization of phosphorylated STAT-3 from nuclear to cytoplasmic, suggesting that vorinostat may inhibit proliferation of CTCL cells by inactivating STAT3.Citation124 Further in vitro work has shown that CTCL patients with high nuclear levels of STAT1 and pSTAT3 are resistant to vorinostat.Citation124 Combination therapy has also been investigated, and PI3 K inhibitors have been found to synergize with vorinostat in reducing cell viability.Citation125

Romidepsin (depsipeptide, Istodax®) is another HDAC inhibitor recently approved by the FDA for patients with relapsed/refractory CTCL. Two Phase II trials were conducted in a total of 167 patients suffering from relapsed, refractory, or advanced CTCL.Citation126,Citation127 Romidepsin was administered intravenously at 14 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle. In both trials, the ORR was 34%, the complete response rate was 6%, the median time to response was 2 months, and median duration of response was longer than 12 months. The most common adverse effects were fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia. Severe adverse effects included leukopenia, lymphopenia, granulocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. Earlier studies have shown that HDAC inhibitors may be associated with electrocardiographic abnormalities, such as QTc interval prolongation.Citation128 In one trial, 9% of patients had QTc prolongation and 80% had asymptomatic T wave flattening or ST segment depression. Citation126 The other trial had no patients with QTcF values >480 milliseconds or an increase of >60 milliseconds over baseline. It was also found that antiemetics might contribute to QTcF prolongation.Citation127

Panobinostat (LBH589) is another HDAC inhibitor that was shown in a Phase I trial to induce clinical responses in CTCL patients.Citation129 Preliminary results of a Phase II trial of oral panobinostat have been reported. Panobinostat was administered at a dose of 20 mg on days 1, 3, and 5 weekly in bexarotene-treated patients and bexarotene-naïve patients. In 62 bexarotene-treated patients, 17.7% achieved a response. In 35 bexarotene-naïve patients, 12.1% achieved a response. Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, pruritus, diarrhea, and hypophosphatemia were the most common grade 3 or 4 toxicities. Two patients had QTcF > 480 milliseconds and four had an increase in QTcF > 60 milliseconds from baseline.Citation130

Another HDAC inhibitor, belinostat (PDX101), is currently being evaluated in a Phase II trial of patients with relapsed/refractory peripheral T cell lymphoma that includes anaplastic large cell lymphoma and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma. The treatment schedule is 1000 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1–5 of a 21-day cycle. Of 19 evaluable patients so far, the ORR was 32% with a median time to response of 8 months.

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies target tumor cells via cell surface markers upregulated on malignant T cells such as CD4, CD52, and CCR4. Zanolimumab (Hu-Max CD4) is a humanized anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody that has been shown in vitro to mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, primarily in CD4 + CD45RO + T cells.Citation131 Zanolimumab also blocks T cell activation by macrophages in Pautrier’s micro abscesses via induction of inhibitory signaling pathways involving SHIP-1 and DOK-1.Citation132 In two Phase II studies done in 47 patients with refractory early-stage and advanced-stage CTCL, zanolimumab was given intravenously at a weekly dose of 280 mg and 560 mg for early-stage patients and 280 mg and 980 mg for late-stage patients. The ORR was 56% in patients with mycosis fungoides treated with a high dose and 15% at a lower dose. In patients with Sézary syndrome, the ORR was 20% in patients treated with a high dose and 25% at a lower dose. Adverse events included skin inflammation (24%) and infections of the skin and upper respiratory tract (49%).Citation133

Alemtuzumab (Campath®), a humanized monoclonal antibody against CD52 surface antigen expressed on most malignant T cells, has been shown to mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity,Citation134,Citation135 complement-mediated cell lysis,Citation136 and apoptosis.Citation137 A Phase II study was conducted in 22 patients with advanced CTCL at a dose of 30 mg intravenously three times a week. The ORR was 55% (32% complete response, 23% partial response). A greater effect was observed in patients with erythrodermic CTCL (69% ORR) than on plaque or tumor CTCL (40%).Citation138 To investigate this preferential effect on erythrodermic CTCL, another Phase II study was conducted in 19 patients with advanced refractory erythrodermic CTCL and found an ORR of 84%.Citation139 Serious adverse events in these studies included infections and hematologic toxicity. Infections, occurring primarily in patients who had received three or more treatments, included cytomegalovirus reactivation, fever of unknown origin, herpes simplex virus reactivation, pulmonary aspergillosis, and Mycobacterium pneumonia. Hematologic toxicities included anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. One study found adverse effects of congestive heart failure and arrhythmias following alemtuzumab treatment.Citation140 However, several studies since have found no correlation with cardiac toxicity.Citation139,Citation141

Chemotherapy

Conventional systemic treatments include chemotherapeutic agents and biologic immunomodulatory therapies. Gemcitabine (Gemzar®) and pegylated doxorubicin (Doxil®) are being used as newer initial single-agent chemotherapeutic choices.Citation142,Citation143 A Phase II trial of gemcitabine reported a 68% ORR in 25 patients with refractory advanced CTCL.Citation144 In advanced untreated CTCL, gemcitabine was shown to result in a 75% response rate in 32 patients.Citation142 Another study showed a response rate of 88% for pegylated liposomal doxorubicin.Citation143

Pralatrexate: targeted antifolate therapy

Methotrexate is the traditional antifolate used in therapy for lymphomas. It inhibits dihydrofolate reductase that converts dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate, which is required for synthesis of thymidylate and purine nucleotides involved in DNA and RNA synthesis. Pralatrexate (Folotyn®) belongs to a class of novel folate analogs, ie, the 10-deazaaminopterins, designed with greater affinity than methotrexate for receptor-reduced folate carrier, leading to improved drug internalization through membrane transport. It is also a better substrate for polyglutamylation than methotrexate, leading to greater intracellular retentionCitation145,Citation146 and 10-fold greater cytotoxicity than methotrexate in lymphoma cell lines.Citation147 Pralatrexate has been approved by the FDA for relapsed or refractory peripheral T cell lymphoma.

Preliminary results of a multicenter dose-escalation Phase II study in 54 patients with relapsed or refractory CTCL have been reported. The starting dose and schedule was 30 mg/m2 intravenously once per week for 3 of 4 weeks. An optimal dose of 15 mg/m2 for 3 of 4 weeks was defined, at which the ORR was 43%. The ORR was 50% at doses greater than 15 mg/m2. Most common grade 1–2 adverse effects included fatigue, mucositis, nausea, edema, epistaxis, pyrexia, constipation, and vomiting. Grade 3 adverse effects included thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, leukopenia, and anemia.Citation148 In another report of 12 patients with mycosis fungoides and large-cell transformation who were part of the multicenter PROPEL (Pralatrexate in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma) trial for patients with peripheral T cell lymphoma, the ORR was 58% via investigator assessment and 25% via independent central review.Citation149,Citation150 Combination therapy with bortezomib is currently under exploration.Citation151

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

The concept of high-dose combined chemotherapy followed by autologous bone marrow transplant or peripheral blood stem cell support has curative potential in various non- Hodgkin lymphomas, but experience in CTCL is limited. Autologous stem cell transplants have yielded disappointing results. Despite reported effective responses with complete response in most patients treated, relapses are frequent and may occur rapidly.Citation152,Citation153 Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with myeloablative conditioning regimens provides a graft-versus-tumor effect and avoids reinfusion of tumor cells, both of which are features lacking in autologous HSCT. However, myeloablation places the patient at high risk for infections and graft-versus-host disease, rendering HSCT difficult to use in the elderly and in those with multiple comorbidities. With the broadened use of nonmyeloablative reduced-intensity conditioning regimens, allogeneic HSCT may now be better suited for patients with CTCL.Citation154 A retrospective study of 60 patients with advanced CTCL who received allogeneic HSCT and either reduced-intensity conditioning or myeloablative conditioning had a complete response rate of 60.5% and an overall survival of 54% at 3 years. Overall survival at 3 years in patients who received reduced-intensity conditioning was 63% compared with 29% in patients who received myeloablative conditioning. The median age of the patients was 46.5 years, indicating that allogeneic HSCT may be an effective treatment in younger as well as older patients.Citation155 In another study of allogeneic HSCT with reduced-intensity conditioning and pretreatment TSEBT for tumor debulking, 58% had a complete response, and overall survival at 2 years was 79%. Causes of mortality included sepsis, metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer, and disease progression.Citation156 Cord blood transplantation has also been attempted with some success in Japan in cases of failure or inability to attempt allogeneic HSCT.Citation157,Citation158

Investigational therapies

Lenalidomide

Lenalidomide (Revlimid®), an analog of thalidomide, is currently approved by the FDA for treatment of myelodys-plastic syndromeCitation159 and refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma.Citation160 Its immunomodulatory properties, such as natural killer and T cell activation with induction of Th1 cytokine production and cytotoxic activity, along with alteration of the tumor cell microenvironment through antiangiogenic, antiproliferative, and proapoptotic properties, provided the rationale to use this agent in patients with CTCL.Citation161 A Phase II trial in 35 patients with advanced/refractory CTCL showed an ORR of 32%, a median time to response of 3 months, and a median duration of response of 4 months.Citation162 The most common side effects were fatigue, lower leg edema, gastrointestinal symptoms, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Temporary tumor flares, characterized by an increase in size/number of skin lesions, tender swelling of lymph nodes, or increase in Sézary cell count, were noted in 25% of patients following initial treatment. Data from this study also suggest that the immunomodulatory effects of lenalidomide might be associated with decreased Treg and CD4+ T cell numbers.

Oligonucleotides (nuclear acid therapeutics)

TLR agonists represent a novel approach to stimulate an effective antitumor immune response in patients with CTCL through augmentation of either dendritic cells or T cell effects. PF-3512676 (CPG-7909, ProMune®) is a TLR-9- activating oligodeoxynucleotide and potent plasmacytoid dendritic cell stimulatorCitation163 that was recently shown in a dose-escalating Phase I trial to induce an ORR in 32% of patients (three complete responses, six partial responses) with treatment-refractory stage IB to IVA CTCL.Citation164 Twenty-eight patients received subcutaneous doses (0.08, 0.16, 0.24, 0.28, 0.32, or 0.36 mg/kg) once weekly for 24 weeks.

Proteasome inhibitors

Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB) is an oncogenic transcription factor normally sequestered in an inactive state by the inhibitory I-kB molecule. Various oncogenic signals activate NF-kB via phosphorylation of I-kB, leading to its degradation via the 26S proteasome. Downstream targets of NF-kB include cIAP1, cIAP2, and Bcl-2.Citation165 Bortezomib inhibits the 26S proteasome and therefore prevents degradation of I-kB and activation of NF-kB.Citation166 It has been shown to induce apoptosis in CTCL via suppression of NF-kB-dependent antiapoptotic genes, cIAP1 and cIAP2, but not Bcl-2.Citation165,Citation167 A Phase II trial was conducted in 15 patients with relapsed/refractory cutaneous T cell lymphoma using a dose of 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every 21 days, for a total of six cycles. The ORR was 67% (17% complete responses, 50% partial responses). Common adverse effects were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and sensory neuropathy.Citation168 Currently, a Phase I trial is being conducted in patients with refractory T cell lymphoma using a combination of bortezomib and 5-azacytidine, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor.

CCR4 antibody

KW-0761, a novel defucosylated humanized monoclonal antibody against CCR4, enhances antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against malignant CTCL cells.Citation169 In vitro studies of KW-0761 using mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome cell lines, primary mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome cells, and mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome mouse models showed not only significant antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity-mediated antitumor activity, but also a synergistic effect with IL-12, IFN-α-2b, and IFN-γ. Phase I studies in adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma and peripheral T cell lymphoma have demonstrated an ORR of 31%, with minimal adverse effects, consisting mainly of hematologic toxicities.Citation170 Phase II studies are currently ongoing in patients with peripheral T cell lymphoma, CTCL, and adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma.

Conclusion

The significant strides that have been made in elucidating the mechanisms of pathogenesis in CTCL have allowed for the development of an extensive repertoire of targeted therapies. Patients with early-stage disease generally have an excellent prognosis and should be treated with skin-directed therapies. While no regimen has been proven to prolong survival in the advanced stages, immunomodulatory regimens are recommended initially to reduce the need for cytotoxic therapies. The existence of multiple mechanisms of oncogenesis in CTCL allows for a variety of mechanistic combinations and more individualized therapy. In more advanced stages of CTCL, treatment efforts should be made for palliation and improvement of quality of life. Unfortunately, other than allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, there are no curative therapies for CTCL.

Disclosures

PM has received research support from Allos Therapeutics, Ligand Pharmaceuticals (now Eisai), Schering-Plough Corporation US Bioscience (now MedImmune), Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Orthobiotech, and Genmab. SH has served as an investigator and consultant, and received research support from Allos Therapeutics, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Kiowa-Kirin, and is a consultant for Merck.

References

- GirardiMHealdPWWilsonLDThe pathogenesis of mycosis fungoidesN Engl J Med2004350191978198815128898

- WillemzeRJaffeESBurgGWHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomasBlood2005105103768378515692063

- BradfordPTDevesaSSAndersonWFToroJRCutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: a population-based study of 3884 casesBlood2009113215064507319279331

- BurgGKempfWCozzioAWHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspectsJ Cutan Pathol2005321064767416293178

- CriscioneVDWeinstockMAIncidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973–2002Arch Dermatol2007143785485917638728

- CampoESwerdlowSHHarrisNLPileriSSteinHJaffeESThe 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applicationsBlood2011117195019503221300984

- van DoornRVan HaselenCWvan Voorst VaderPCMycosis fungoides: disease evolution and prognosis of 309 Dutch patientsArch Dermatol2000136450451010768649

- KimYHLiuHLMraz-GernhardSVargheseAHoppeRTLong- term outcome of 525 patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical prognostic factors and risk for disease progressionArch Dermatol2003139785786612873880

- WainEMOrchardGEWhittakerSJSpittleMFRussell-JonesROutcome in 34 patients with juvenile-onset mycosis fungoides: a clinical, immunophenotypic, and molecular studyCancer200398102282229014601100

- CrowleyJJNikkoAVargheseAHoppeRTKimYHMycosis fungoides in young patients: clinical characteristics and outcomeJ Am Acad Dermatol1998385 Pt 16967019591813

- BunnPAJrLambergSIReport of the committee on staging and classification of cutaneous T-cell lymphomasCancer Treat Rep1979634725728445521

- OlsenEVonderheidEPimpinelliNRevisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)Blood200711061713172217540844

- AgarNSWedgeworthECrichtonSSurvival outcomes and prognostic factors in mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome: validation of the revised International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer staging proposalJ Clin Oncol201028314730473920855822

- GeramiPRosenSKuzelTBooneSLGuitartJFolliculotropic mycosis fungoides: an aggressive variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphomaArch Dermatol2008144673874618559762

- OlsenEAWhittakerSKimYHClinical end points and response criteria in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a consensus statement of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas, the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of CancerJ Clin Oncol201129182598260721576639

- BergerCLWarburtonDRaafatJLoGerfoPEdelsonRLCutaneous T-cell lymphoma: neoplasm of T cells with helper activityBlood1979534642651311642

- SaedGFivensonDPNaiduYNickoloffBJMycosis fungoides exhibits a Th1-type cell-mediated cytokine profile whereas Sezary syndrome expresses a Th2-type profileJ Invest Dermatol1994103129338027577

- ChongBFWilsonAJGibsonHMImmune function abnormalities in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cytokine expression differentiates stages of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/mycosis fungoidesClin Cancer Res200814364665318245523

- KrejsgaardTOdumNGeislerCWasikMAWoetmannARegulatory T cells and immunodeficiency in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndromeLeukemia2011 [Epub ahead of print.]

- WeaverCTHattonRDManganPRHarringtonLEIL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineagesAnnu Rev Immunol20072582185217201677

- LowesMABowcockAMKruegerJGPathogenesis and therapy of psoriasisNature2007445713086687317314973

- CireeAMichelLCamilleri-BroetSExpression and activity of IL-17 in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome)Int J Cancer2004112111312015305382

- KrejsgaardTRalfkiaerUClasen-LindeEMalignant cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells express IL-17 utilizing the Jak3/Stat3 signaling pathwayJ Invest Dermatol201113161331133821346774

- AsadullahKHaeussler-QuadeAGellrichSIL-15 and IL-16 overexpression in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: stage- dependent increase in mycosis fungoides progressionExp Dermatol20009424825110949545

- RichmondJTuzovaMParksAInterleukin-16 as a marker of Sezary syndrome onset and stageJ Clin Immunol2011311395020878214

- SamimiSBenoitBEvansKIncreased programmed death-1 expression on CD4+ T cells in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: implications for immune suppressionArch Dermatol2010146121382138820713771

- van der FitsLvan KesterMSQinYMicroRNA-21 expression in CD4+ T cells is regulated by STAT3 and is pathologically involved in Sezary syndromeJ Invest Dermatol2011131376276821085192

- CetinozmanFJansenPMWillemzeRExpression of programmed death-1 in primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous pseudo-T-cell lymphoma, and other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomaAm J Surg Pathol201236110911621989349

- Lonsdor fASHwangSTEnkAHChemokine receptors in T-cell-mediated diseases of the skinJ Invest Dermatol2009129112552256619474804

- WuXSLonsdorfASHwangSTCutaneous T-cell lymphoma: roles for chemokines and chemokine receptorsJ Invest Dermatol200912951115111919242508

- FerencziKFuhlbriggeRCPinkusJPinkusGSKupperTSIncreased CCR4 expression in cutaneous T cell lymphomaJ Invest Dermatol200211961405141012485447

- CampbellJJO’ConnellDJWurbelMACutting edge: Chemokine receptor CCR4 is necessary for antigen-driven cutaneous accumulation of CD4 T cells under physiological conditionsJ Immunol200717863358336217339428

- NotohamiprodjoMSegererSHussRCCR10 is expressed in cutaneous T-cell lymphomaInt J Cancer2005115464164715700309

- Sokolowska-WojdyloMWenzelJGaffalECirculating clonal CLA(+) and CD4(+) T cells in Sezary syndrome express the skin-homing chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR10 as well as the lymph node-homing chemokine receptor CCR7Br J Dermatol2005152225826415727636

- AndoKOzakiTYamamotoHPolo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) inhibits p53 function by physical interaction and phosphorylationJ Biol Chem200427924255492556115024021

- LuoJEmanueleMJLiDA genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogeneCell2009137583584819490893

- WalunasTLLenschowDJBakkerCYCTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activationImmunity1994154054137882171

- SchneiderHValkELeungRRuddCECTLA-4 activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-K) and protein kinase B (PKB/AKT) sustains T-cell anergy without cell deathPLoS One2008312e384219052636

- TakahashiTTagamiTYamazakiSImmunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4J Exp Med2000192230331010899917

- WingKOnishiYPrieto-MartinPCTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell functionScience2008322589927127518845758

- WongHKWilsonAJGibsonHMIncreased expression of CTLA-4 in malignant T-cells from patients with mycosis fungoides – cutaneous T cell lymphomaJ Invest Dermatol2006126121221916417239

- HermanJGBaylinSBGene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylationN Engl J Med2003349212042205414627790

- JonesPABaylinSBThe fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancerNat Rev Genet20023641542812042769

- van DoornRZoutmanWHDijkmanREpigenetic profiling of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: promoter hypermethylation of multiple tumor suppressor genes including BCL7a, PTPRG, and p73J Clin Oncol200523173886389615897551

- NavasICOrtiz-RomeroPLVilluendasRp16(Inatural killer 4a) gene alterations are frequent in lesions of mycosis fungoidesAm J Pathol200015651565157210793068

- ScarisbrickJJWoolfordAJCalonjeEFrequent abnormalities of the p15 and p16 genes in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndromeJ Invest Dermatol2002118349349911874489

- GallardoFEstellerMPujolRMCostaCEstrachTServitjeOMethylation status of the p15, p16 and MGMT promoter genes in primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomasHaematologica200489111401140315531468

- ScarisbrickJJMitchellTJCalonjeEOrchardGRussell-JonesRWhittakerSJMicrosatellite instability is associated with hypermethylation of the hMLH1 gene and reduced gene expression in mycosis fungoidesJ Invest Dermatol2003121489490114632210

- MarksPRifkindRARichonVMBreslowRMillerTKellyWKHistone deacetylases and cancer: causes and therapiesNat Rev Cancer20011319420211902574

- ZhangCRichonVNiXTalpurRDuvicMSelective induction of apoptosis by histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma cells: relevance to mechanism of therapeutic actionJ Invest Dermatol200512551045105216297208

- ContassotEKerlKRoquesSResistance to FasL and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis in Sezary syndrome T-cells associated with impaired death receptor and FLICE-inhibitory protein expressionBlood200811194780478718314443

- DereureOLeviEVonderheidECKadinMEInfrequent Fas mutations but no Bax or p53 mutations in early mycosis fungoides: a possible mechanism for the accumulation of malignant T lymphocytes in the skinJ Invest Dermatol2002118694995612060388

- DereureOPortalesPClotJGuilhouJJDecreased expression of Fas (APO-1/CD95) on peripheral blood CD4+ T lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphomasBr J Dermatol200014361205121011122022

- Zoi-ToliOVermeerMHDe VriesEVan BeekPMeijerCJWillemzeRExpression of Fas and Fas-ligand in primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL): association between lack of Fas expression and aggressive types of CTCLBr J Dermatol2000143231331910951138

- van DoornRDijkmanRVermeerMHStarinkTMWillemzeRTensenCPA novel splice variant of the Fas gene in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphomaCancer Res200262195389539212359741

- JonesCLWainEMChuCCDownregulation of Fas gene expression in Sezary syndrome is associated with promoter hypermethylationJ Invest Dermatol201013041116112519759548

- McGregorJMCrookTFraser-AndrewsEASpectrum of p53 gene mutations suggests a possible role for ultraviolet radiation in the pathogenesis of advanced cutaneous lymphomasJ Invest Dermatol1999112331732110084308

- Kandolf SekulovicLCikotaBJovicMThe role of apoptosis and cell-proliferation regulating genes in mycosis fungoidesJ Dermatol Sci2009551535619324523

- DummerRMichieSAKellDExpression of bcl-2 protein and Ki-67 nuclear proliferation antigen in benign and malignant cutaneous T-cell infiltratesJ Cutan Pathol199522111177751472

- NielsenMKaestelCGEriksenKWInhibition of constitutively activated Stat3 correlates with altered Bcl-2/Bax expression and induction of apoptosis in mycosis fungoides tumor cellsLeukemia199913573573810374878

- EckerdtFYuanJStrebhardtKPolo-like kinases and oncogenesisOncogene200524226727615640842

- IkezoeTYangJNishiokaCA novel treatment strategy targeting polo-like kinase 1 in hematological malignanciesLeukemia20092391564157619421227

- SchmitTLZhongWNihalMAhmadNPolo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in non-melanoma skin cancersCell Cycle20098172697270219652546

- SchmitTLZhongWSetaluriVSpiegelmanVSAhmadNTargeted depletion of Polo-like kinase (Plk) 1 through lentiviral shRNA or a small-molecule inhibitor causes mitotic catastrophe and induction of apoptosis in human melanoma cellsJ Invest Dermatol2009129122843285319554017

- StutzNNihalMWoodGSPolo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in cutaneous T-cell lymphomaBr J Dermatol2011164481482121070201

- NihalMStutzNSchmitTAhmadNWoodGSPolo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) is expressed by cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs), and its downregulation promotes cell cycle arrest and apoptosisCell Cycle20111081303131121436619

- SchoffskiPPolo-like kinase (PLK) inhibitors in preclinical and early clinical development in oncologyOncologist200914655957019474163

- MrossKFrostASteinbildSPhase I dose escalation and pharmacokinetic study of BI 2536, a novel Polo-like kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumorsJ Clin Oncol200826345511551718955456

- OlmosDBarkerDSharmaRPhase I study of GSK461364, a specific and competitive Polo-like kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid malignanciesClin Cancer Res201117103420343021459796

- JimenoALiJMessersmithWAPhase I study of ON 01910. Na, a novel modulator of the Polo-like kinase 1 pathway, in adult patients with solid tumorsJ Clin Oncol200826345504551018955447

- GarlandLLTaylorCPilkingtonDLCohenJLVon HoffDDA phase I pharmacokinetic study of HMN-214, a novel oral stilbene derivative with Polo-like kinase-1-interacting properties, in patients with advanced solid tumorsClin Cancer Res200612175182518916951237

- ChenJFiskusWEatonKCotreatment with Bcl-2 antagonist sensitizes cutaneous T-cell lymphoma to lethal action of HDAC7- Nur77-based mechanismBlood2009113174038404819074726

- LaharanneEOumouhouNBonnetFGenome-wide analysis of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas identifies three clinically relevant classesJ Invest Dermatol201013061707171820130593

- LinWMLewisJMFillerRBCharacterization of the DNA copy- number genome in the blood of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma patientsJ Invest Dermatol2012132118819721881587

- VermeerMHvan DoornRDijkmanRNovel and highly recurrent chromosomal alterations in Sezary syndromeCancer Res20086882689269818413736

- GarzonRMarcucciGCroceCMTargeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challengesNat Rev Drug Discov201091077578920885409

- RalfkiaerUHagedornPHBangsgaardNDiagnostic microRNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)Blood2011118225891590021865341

- van KesterMSBallabioEBennerMFmiRNA expression profiling of mycosis fungoidesMol Oncol20115327328021406335

- NarducciMGArcelliDPicchioMCMicroRNA profiling reveals that miR-21, miR486 and miR-214 are upregulated and involved in cell survival in Sezary syndromeCell Death Dis20112e15121525938

- BallabioEMitchellTvan KesterMSMicroRNA expression in Sezary syndrome: identification, function, and diagnostic potentialBlood201011671105111320448109

- KayeFJBunnPAJrSteinbergSMA randomized trial comparing combination electron-beam radiation and chemotherapy with topical therapy in the initial treatment of mycosis fungoidesN Engl J Med198932126178417902594037

- HerrmannJJRoenigkHHJrHurriaATreatment of mycosis fungoides with photochemotherapy (PUVA): long-term follow-upJ Am Acad Dermatol1995332 Pt 12342427622650

- HonigsmannHPhototherapy and photochemotherapySemin Dermatol19909184902203448

- QuerfeldCRosenSTKuzelTMLong-term follow-up of patients with early-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma who achieved complete remission with psoralen plus UV-A monotherapyArch Dermatol2005141330531115781671

- TrautingerFKnoblerRWillemzeREORTC consensus recommendations for the treatment of mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndromeEur J Cancer20064281014103016574401

- RosenSTQuerfeldCKuzelTMGuitartJCutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas: A Guide for the Community Oncologist2nd edThe Oncology Group, CMPMedica2008

- ZackheimHSTreatment of patch-stage mycosis fungoides with topical corticosteroidsDermatol Ther200316428328714686970

- ZackheimHSKashani-SabetMAminSTopical corticosteroids for mycosis fungoides. Experience in 79 patientsArch Dermatol199813489499549722724

- KimYHManagement with topical nitrogen mustard in mycosis fungoidesDermatol Ther200316428829814686971

- HealdPMehlmauerMMartinAGCrowleyCAYocumRCReichSDTopical bexarotene therapy for patients with refractory or persistent early-stage cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: results of the phase III clinical trialJ Am Acad Dermatol200349580181514576658

- ApisarnthanaraxNTalpurRWardSNiXKimHWDuvicMTazarotene 0.1% gel for refractory mycosis fungoides lesions: an open-label pilot studyJ Am Acad Dermatol200450460060715034511

- Martinez-GonzalezMCVerea-HernandoMMYebra-PimentelMTDel PozoJMazairaMFonsecaEImiquimod in mycosis fungoidesEur J Dermatol200818214815218424373

- DeethsMJChapmanJTDellavalleRPZengCAelingJLTreatment of patch and plaque stage mycosis fungoides with imiquimod 5% creamJ Am Acad Dermatol200552227528015692473

- SuchinKRJunkins-HopkinsJMRookAHTreatment of stage IA cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with topical application of the immune response modifier imiquimodArch Dermatol200213891137113912224972

- ArdigoMCotaCBerardescaEUnilesional mycosis fungoides successfully treated with imiquimodEur J Dermatol200616444616935811

- UrosevicMFujiiKCalmelsBType I IFN innate immune response to adenovirus-mediated IFN-gamma gene transfer contributes to the regression of cutaneous lymphomasJ Clin Invest2007117102834284617823660

- DummerREichmullerSGellrichSPhase II clinical trial of intratumoral application of TG1042 (adenovirus-interferon-gamma) in patients with advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphomas and multilesional cutaneous B-cell lymphomasMol Ther20101861244124720372104

- JinSPJeonYKChoKHChungJHExcimer laser therapy (308 nm) for mycosis fungoides palmaris et plantaris: a skin-directed and anatomically feasible treatmentBr J Dermatol2010163365165320377583

- KontosAPKerrHAMalickFFivensonDPLimHWWongHK308-nm excimer laser for the treatment of lymphomatoid papulosis and stage IA mycosis fungoidesPhotodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed200622316817116719874

- MoriMCampolmiPMaviliaLRossiRCappugiPPimpinelliNMonochromatic excimer light (308 nm) in patch-stage IA mycosis fungoidesJ Am Acad Dermatol200450694394515153899

- NisticoSCostanzoASaracenoRChimentiSEfficacy of monochromatic excimer laser radiation (308 nm) in the treatment of early stage mycosis fungoidesBr J Dermatol2004151487787915491430

- PasseronTZakariaWOstovariNEfficacy of the 308-nm excimer laser in the treatment of mycosis fungoidesArch Dermatol2004140101291129315492207

- MeisenheimerJLTreatment of mycosis fungoides using a 308-nm excimer laser: two case studiesDermatol Online J20061271117459297

- EdstromDWHedbladMALong-term follow-up of photodynamic therapy for mycosis fungoidesActa Derm Venereol200888328829018480938

- CoorsEAvon den DrieschPTopical photodynamic therapy for patients with therapy-resistant lesions of cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Am Acad Dermatol200450336336714988676

- MortonCAMcKennaKERhodesLEGuidelines for topical photodynamic therapy: updateBr J Dermatol200815961245126618945319

- DebuAGirardCKlugerNGuillotBDereureOTopical methyl aminolaevulinate-photodynamic therapy in erosive facial mycosis fungoidesBr J Dermatol2010163488488520854405

- ZaneCVenturiniMSalaRCalzavara-PintonPPhotodynamic therapy with methylaminolevulinate as a valuable treatment option for unilesional cutaneous T-cell lymphomaPhotodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed200622525425816948827

- HegyiJFreyTArenbergerPUnilesional mycosis fungoides treated with photodynamic therapy. A case reportActa Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat2008172757818709294

- LamMLeeYDengMPhotodynamic therapy with the silicon phthalocyanine pc 4 induces apoptosis in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndromeAdv Hematol2010201089616121197103

- RookAHWoodGSDuvicMVonderheidECTobiaACabanaBA Phase II placebo-controlled study of photodynamic therapy with topical hypericin and visible light irradiation in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and psoriasisJ Am Acad Dermatol201063698499020889234

- SuchinKRCucchiaraAJGottleibSLTreatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma with combined immunomodulatory therapy: a 14-year experience at a single institutionArch Dermatol200213881054106012164743

- RaphaelBAShinDBSuchinKRHigh clinical response rate of Sezary syndrome to immunomodulatory therapies: prognostic markers of responseArch Dermatol2011147121410141521844430

- RichardsonSKMcGinnisKSShapiroMExtracorporeal photopheresis and multimodality immunomodulatory therapy in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Cutan Med Surg20037Suppl 481212958701

- OlsenEARosenSTVollmerRTInterferon alfa-2a in the treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphomaJ Am Acad Dermatol19892033954072783939

- KuzelTMGilyonKSpringerEInterferon alfa-2a combined with phototherapy in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Natl Cancer Inst19908232032072296050

- RupoliSGoteriGPuliniSLong-term experience with low-dose interferon-alpha and PUVA in the management of early mycosis fungoidesEur J Haematol200575213614516000130

- SalehMNLeMaistreCFKuzelTMAntitumor activity of DAB389IL-2 fusion toxin in mycosis fungoidesJ Am Acad Dermatol199839163739674399

- PrinceHMDuvicMMartinAPhase III placebo-controlled trial of denileukin diftitox for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Clin Oncol201028111870187720212249

- FossFDuvicMOlsenEAPredictors of complete responses with denileukin diftitox in cutaneous T-cell lymphomaAm J Hematol201186762763021674574

- ZainJO’ConnorOATargeting histone deacetyalses in the treatment of B- and T-cell malignanciesInvest New Drugs201028 Suppl 1S58S7821132350

- OlsenEAKimYHKuzelTMPhase IIb multicenter trial of vorinostat in patients with persistent, progressive, or treatment refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Clin Oncol200725213109311517577020

- DuvicMTalpurRNiXPhase 2 trial of oral vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, SAHA) for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)Blood20071091313916960145

- FantinVRLobodaAPaweletzCPConstitutive activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription predicts vorinostat resistance in cutaneous T-cell lymphomaCancer Res200868103785379418483262

- WozniakMBVilluendasRBischoffJRVorinostat interferes with the signaling transduction pathway of T-cell receptor and synergizes with phosphoinositide-3 kinase inhibitors in cutaneous T-cell lymphomaHaematologica201095461362120133897

- PiekarzRLFryeRTurnerMPhase II multi-institutional trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin as monotherapy for patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Clin Oncol200927325410541719826128

- WhittakerSJDemierreMFKimEJFinal results from a multicenter, international, pivotal study of romidepsin in refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Clin Oncol201028294485449120697094

- PiekarzRLFryeARWrightJJCardiac studies in patients treated with depsipeptide, FK228, in a phase II trial for T-cell lymphomaClin Cancer Res200612123762377316778104

- EllisLPanYSmythGKHistone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat induces clinical responses with associated alterations in gene expression profiles in cutaneous T-cell lymphomaClin Cancer Res200814144500451018628465

- DuvicMBeckerJCDalleSPhase II trial of oral panobinostat (LBH589) in patients with refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts2008112111005

- SkovLKragballeKZachariaeCHuMax-CD4: a fully human monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody for the treatment of psoriasis vulgarisArch Dermatol2003139111433143914623703

- RiderDAHavenithCEde RidderRA human CD4 monoclonal antibody for the treatment of T-cell lymphoma combines inhibition of T-cell signaling by a dual mechanism with potent Fc-dependent effector activityCancer Res200767209945995317942927

- KimYHDuvicMObitzEClinical efficacy of zanolimumab (HuMax-CD4): two phase 2 studies in refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphomaBlood2007109114655466217311990

- DyerMJHaleGHayhoeFGWaldmannHEffects of Campath-1 antibodies in vivo in patients with lymphoid malignancies: influence of antibody isotypeBlood1989736143114392713487

- GreenwoodJClarkMWaldmannHStructural motifs involved in human IgG antibody effector functionsEur J Immunol1993235109811048477804

- HeitWBunjesDWiesnethMEx vivo T-cell depletion with the monoclonal antibody Campath-1 plus human complement effectively prevents acute graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic bone marrow transplantationBr J Haematol19866434794863539172

- RowanWTiteJTopleyPBrettSJCross-linking of the Campath-1 antigen (CD52) mediates growth inhibition in human B- and T-lymphoma cell lines, and subsequent emergence of CD52-deficient cellsImmunology19989534274369824507

- LundinJHagbergHReppRPhase 2 study of alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) in patients with advanced mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndromeBlood2003101114267427212543862

- QuerfeldCMehtaNRosenSTAlemtuzumab for relapsed and refractory erythrodermic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a single institution experience from the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer CenterLeuk Lymphoma200950121969197619860617

- LenihanDJAlencarAJYangDKurzrockRKeatingMJDuvicMCardiac toxicity of alemtuzumab in patients with mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndromeBlood2004104365565815073032

- LundinJKennedyBDeardenCDyerMJOsterborgANo cardiac toxicity associated with alemtuzumab therapy for mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndromeBlood2005105104148414915867423

- MarchiEAlinariLTaniMGemcitabine as frontline treatment for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: phase II study of 32 patientsCancer2005104112437244116216001

- WollinaUDummerRBrockmeyerNHMulticenter study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphomaCancer2003985993100112942567

- DuvicMTalpurRWenSKurzrockRDavidCLApisarnthanaraxNPhase II evaluation of gemcitabine monotherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphomaClin Lymphoma Myeloma200671515816879770

- SirotnakFMDeGrawJIMoccioDMSamuelsLLGoutasLJNew folate analogs of the 10-deaza-aminopterin series. Basis for structural design and biochemical and pharmacologic propertiesCancer Chemother Pharmacol198412118256690069

- DeGrawJIColwellWTPiperJRSirotnakFMSynthesis and antitumor activity of 10-propargyl-10-deazaaminopterinJ Med Chem19933615222822318340923

- WangESO’ConnorOSheYZelenetzADSirotnakFMMooreMAActivity of a novel anti-folate (PDX, 10-propargyl 10-deazaaminopterin) against human lymphoma is superior to methotrexate and correlates with tumor RFC-1 gene expressionLeuk Lymphoma20034461027103512854905

- HorwitzSMKimYHFossFMIdentification of an active, well-tolerated dose of pralatrexate in patients with relapsed or refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL): final results of a multicenter dose-finding studyASH Annual Meeting Abstracts2010116212800

- FossFMHorwitzSMPinter-BrownLPralatrexate is an effective treatment for heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory transformed mycosis fungoides (tMF)ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts2010116211762

- O’ConnorOAProBPinter-BrownLPralatrexate in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results from the pivotal PROPEL studyJ Clin Oncol20112991182118921245435

- MarchiEPaoluzziLScottoLPralatrexate is synergistic with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in in vitro and in vivo models of T-cell lymphoid malignanciesClin Cancer Res201016143648365820501616

- OlavarriaEChildFWoolfordAT-cell depletion and autologous stem cell transplantation in the management of tumour stage mycosis fungoides with peripheral blood involvementBr J Haematol2001114362463111552988

- Russell-JonesRChildFOlavarriaEWhittakerSSpittleMApperleyJAutologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in tumor-stage mycosis fungoides: predictors of disease-free survivalAnn N Y Acad Sci200194114715411594568

- BaronFStorbRAllogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation following nonmyeloablative conditioning as treatment for hematologic malignancies and inherited blood disordersMol Ther2006131264116280257

- DuarteRFCanalsCOnidaFAllogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients with mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a retrospective analysis of the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow TransplantationJ Clin Oncol201028294492449920697072

- DuvicMDonatoMDabajaBTotal skin electron beam and non-myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in advanced mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndromeJ Clin Oncol201028142365237220351328

- FukushimaTHorioKMatsuoESuccessful cord blood transplantation for mycosis fungoidesInt J Hematol200888559659818998050

- TsujiHWadaTMurakamiMTwo cases of mycosis fungoides treated by reduced-intensity cord blood transplantationJ Dermatol201037121040104521083707

- ListAKurtinSRoeDJEfficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromesN Engl J Med2005352654955715703420

- RichardsonPGSchlossmanRLWellerEImmunomodulatory drug CC-5013 overcomes drug resistance and is well tolerated in patients with relapsed multiple myelomaBlood200210093063306712384400

- BartlettJBDredgeKDalgleishAGThe evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agentsNat Rev Cancer20044431432215057291

- QuerfeldCRosenSTGuitartJPhase II multicenter trial of lenalidomide: clinical and immunomodulatory effects in patients with CTCLASH Annual Meeting Abstracts2011118211638

- KriegAMDevelopment of TLR9 agonists for cancer therapyJ Clin Invest200711751184119417476348

- KimYHGirardiMDuvicMPhase I trial of a Toll-like receptor 9 agonist, PF-3512676 (CPG 7909), in patients with treatment-refractory, cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Am Acad Dermatol201063697598320888065

- JuvekarAMannaSRamaswamiSBortezomib induces nuclear translocation of IkappaBalpha resulting in gene-specific suppression of NF-kappaB – dependent transcription and induction of apoptosis in CTCLMol Cancer Res20119218319421224428

- PalombellaVJRandoOJGoldbergALManiatisTThe ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-kappa B1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-kappa BCell19947857737858087845

- SorsAJean-LouisFPelletCDown-regulating constitutive activation of the NF-kappaB canonical pathway overcomes the resistance of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma to apoptosisBlood200610762354236316219794

- ZinzaniPLMusuracaGTaniMPhase II trial of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphomaJ Clin Oncol200725274293429717709797

- ItoAIshidaTYanoHDefucosylated anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody exercises potent ADCC-mediated antitumor effect in the novel tumor-bearing humanized NOD/Shi-scid, IL-2Rgamma(null) mouse modelCancer Immunol Immunother20095881195120619048251

- YamamotoKUtsunomiyaATobinaiKPhase I study of KW-0761, a defucosylated humanized anti-CCR4 antibody, in relapsed patients with adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphomaJ Clin Oncol20102891591159820177026

- SirotnakFMDeGrawJISchmidFAGoutasLJMoccioDMNew folate analogs of the 10-deaza-aminopterin series. Further evidence for markedly increased antitumor efficacy compared with methotrexate in ascitic and solid murine tumor modelsCancer Chemother Pharmacol198412126306690070