Abstract

Self-management is becoming increasingly important in COPD health care although it remains difficult to embed self-management into routine clinical care. The implementation of self-management is understood as a complex interaction at the level of patient, health care provider (HCP), and health system. Nonetheless there is still a poor understanding of the barriers and effective facilitators. Comprehension of these determinants can have significant implications in optimizing self-management implementation and give further directions for the development of self-management interventions. Data were collected among COPD patients (N=46) and their HCPs (N=11) in three general practices and their collaborating affiliated hospitals. Mixed methods exploration of the data was conducted and collected by interviews, video-recorded consultations (N=50), and questionnaires on consultation skills. Influencing determinants were monitored by 1) interaction and communication between the patient and HCP, 2) visible and invisible competencies of both the patient and the HCP, and 3) degree of embedding self-management into the health care system. Video observations showed little emphasis on effective behavioral change and follow-up of given lifestyle advice during consultation. A strong presence of COPD assessment and monitoring negatively affects the patient-centered communication. Both patients and HCPs experience difficulties in defining personalized goals. The satisfaction of both patients and HCPs concerning patient centeredness during consultation was measured by the patient feedback questionnaire on consultation skills. The patients scored high (84.3% maximum score) and differed from the HCPs (26.5% maximum score). Although the patient-centered approach accentuating self-management is one of the dominant paradigms in modern medicine, our observations show several influencing determinants causing difficulties in daily practice implementation. This research is a first step unravelling the determinants of self-management leading to a better understanding.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, COPD is listed among the top three leading causes of death in 2030.Citation1 COPD is currently ranked sixth in the Dutch mortality ranking list.Citation2,Citation3 Because of the aging population, it is expected that the number of COPD patients will increase by 38% between 2005 and 2025.Citation4 Apart from the expected loss in both years of life and health-related quality of life among many patients, this development influences both the accessibility and affordability of COPD care. Consequently, self-management is becoming increasingly more important,Citation5 referring to the individual’s ability to manage symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic disease.Citation6 Over the last decade, an increase is seen in general practice-based nurse specialists, improving consultation to chronic care patients, transferring knowledge of lifestyle awareness and optimized prevention.Citation7 Furthermore, a variety of (e-health) interventions and tools are available for COPD patients, supporting in handling symptoms, maintenance of physical functioning, and medical management.Citation8 These self-management interventions are understood as all programs and techniques enabling patients to assume responsibility for managing one or more aspects of COPD.Citation9 The majority of those interventions are based on the cognitive behavioral therapyCitation10–Citation15 increasing problem solving and gaining confidence in one’s own ability to perform a particular behavior, called self-efficacy.Citation16

Another used model refers to the willingness and motivation of individuals to change behavior.Citation17,Citation18 Interventions based on this theory focus on exploring the motivation for behavior change and next adjusting the treatment to this.

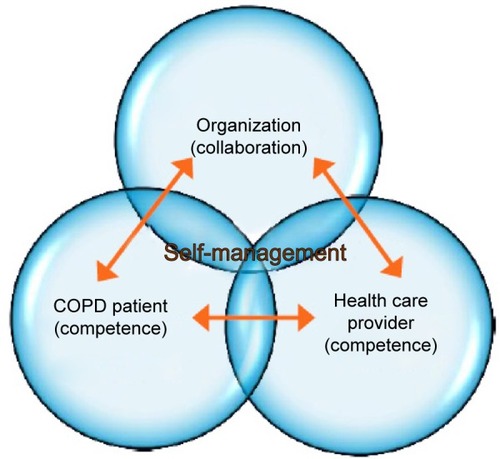

Although achieving behavior change is the ultimate goal, a most challenging task is influencing it. There are numerous determinants affecting health behavior and lifestyle, which can be explained by a complex interaction at the level of the patient, health care provider (HCP), health care system, and community.Citation19,Citation20 First, it is essential that patients feel supported in the clinical encounter, increase their motivation and self-efficacy preferably in an equal patient–HCP partnership making shared decisions possible.Citation21 The patient’s perspective is essential, and the role of the HCP shifts from a leading to a more coaching role during consultation.Citation22 This commitment to equality in which there occurs a rearrangement of tasks and responsibilities is also called “patient empowerment”.Citation23

Second, both the patients and the HCPs need competencies to optimally interact during this encounter. Spencer and SpencerCitation24 distinguish visible and less-visible underlying competencies indicating ways of behaving or thinking, which generalizes across a wide range of situations and endures for long period of time. Among these visible competencies are the degree of knowledge, general and communication skills of both patients and HCPs. Examples of less visible underlying competencies of both patients and HCPs are: beliefs (attitudes), motivation, values, motives, and personality characteristics. These can influence the consultation encounter to a large extent. The degree of self-efficacy can also be seen as one of these invisible competencies. Within chronic disease management, it is seen as one of the most essential competencies to achieve behavioral change.Citation25,Citation9

A third important mechanism empowering patients is the embedding of self-management in the organizational care processCitation26 as understood according to the chronic care model.Citation27,Citation28 Because of the numerous health care professionals involved in COPD treatment in both primary care and hospital care, good cooperation and coordination between the patient and the various levels of health care are essential. Another less accentuated influencing organizational factor is the duration of the consultation time on self-management.

Despite the many new developments, the wide range of available (e-health) tools and the efforts made by the patients and HCPs, accomplishing changes in lifestyle and optimal self-management, seem not feasible for everyone. This is evidenced by the high level of medication noncompliance,Citation29–Citation33 the lower psychic well-being, and decreased quality of life, reported among people with a wide range of chronic diseases.Citation34–Citation38 Improving the patient’s motivation must always be the first step in developing an intervention promoting self-management.Citation39 Yet, this critical area of concern is often lacking in today’s self-management interventions.Citation40 Moreover, the implementation of (e-health) self-management interventions seems to be still having difficulties embedding into routine health care and normal standard care.Citation41,Citation42 While effectiveness has been demonstrated of using action plans in early detection of exacerbations,Citation43,Citation44 just a minority of 14% of the COPD patients in the Netherlands actually use them. The action plans are still highly focused on medical regimes and to a lesser extent on adapting lifestyle and setting up personal goals.Citation45 Similar modest numbers apply to used motivational interviewing techniques during consultation by general practitioners and community nurses.Citation46 There is still a poor understanding of both the effective facilitators as barriers concerning the implementation of self-management. A better comprehension of these facilitators and barriers can have significant implications for the direction of further development of self-management interventions and the optimization of the implementation of self-management in health care.

In the current study, we adopted a mixed methods approach investigating possible effective facilitators and barriers for the implementation of self-management in both general practices and their affiliated hospitals. The focus of the study lied on the extension of self-management implementation and was affected by

the interaction and “communication” between the patient and the HCP,Citation23,Citation45

the visible and invisible “competencies” of both the patient and the HCP,Citation24

the degree of “self-management embedding” into the health care system.Citation19,Citation27,Citation26

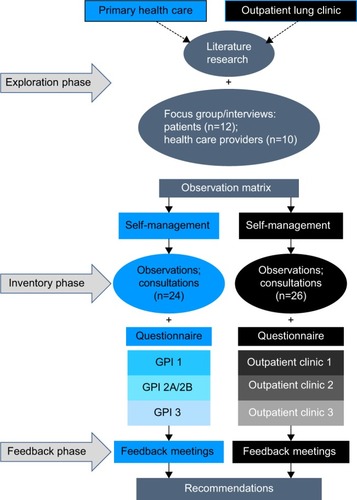

Methods

The theoretical model is based on the chronic care model, providing a framework for understanding and addressing chronic illness care, whereas self-management is further explained according to the social cognitive behavioral theory.Citation27,Citation16 A model is used in identifying the numerous determinants affecting health behavior and lifestyle. Influencing factors are subdivided at patient, HCP, health care system, and community level ().Citation47 Participants of the research were both patients and their HCPs of Dutch general practices and their affiliated outpatient lung clinics with a follow-up period of a year. Data were used from baseline questionnaires, interviews, and observations of consultations with patients and HCPs; collected sequentially in three different phases (exploratory, inventory, and feedback phase) according to the three-dimensional typology of mixed methods designs ().Citation48 The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Board of the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMC Utrecht) prior to commencement.

Participant selection and setting

General practices and outpatient clinics were recruited by contacting the medical director or highest responsible person asking to participate in the research. Three matching couples were formed based on their regional collaboration, each couple consisting of a general practice with their affiliated hospital. The HCPs of the participating organizations recruited primary care patients and hospital outpatients according to the inclusion criteria doctor-diagnosed COPD, aged 18 years or older and willingness to participate. The HCPs informed the patients by telephone; subsequently detailed information about the study was sent by post. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant, and the research assistant double-checked the compliance with the study criteria.

Data collection and analysis

Exploratory phase

Insight is gained of the perspectives of both patients and caregivers about possible influencing factors to promote and implement self-management in daily practice. The initially planned patient focus groups in each participating primary care and outpatient clinic were rescheduled into individual interviews, after one focus group of five persons was held. In the interviews, it was easier to elaborate on the topics.

Ten caregivers with different professional backgrounds and 12 patients from primary care and outpatient clinics were purposively selected and participated in semistructured interviews. All interviews were conducted by the same researcher using a topic list developed according to the principles of Kvale.Citation49 Recordings were transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription service and subsequently compared with the audio recordings for completeness and accuracy. Both content and thematic analyses were used based on the framework approach.Citation50 Interviews were coded by two separately working researchers with the use of the data analysis software of Dedoose, a web-based program for mixed methods research. The top 9 most-coded key concepts (%) from both the patients and the HCPs were collected and compared.

Inventory phase

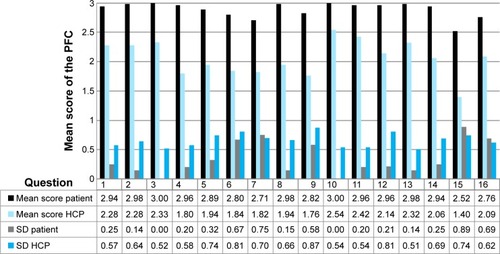

Influencing factors of implementing and promoting self-management were observed in real-life settings by videotaping consultations (N=50) obtained by 46 patients and 11 HCPs (4 patients had a second consult) both from the participating general practices and their affiliated outpatient clinics. Perceived patient-centeredness during consultation was measured afterwards by both the patients and the HCPs by the validated 16-item (4-point scale) dyadic patient feedback questionnaire on consultation skills (PFC; ).Citation51 The PFC questionnaire has two parallel versions: a patient feedback version and a HCP self-assessment version.Citation51

Table 1 Patient feedback questionnaire on consultation skills; 4-point scale (completely, mostly, a little, not at all)

An observation matrix was used analyzing the video content of the consultations. Development of the matrix was based on the most common-coded key concepts extracted from HCPs and patients’ interviews in the exploratory phase, combined with the foremost contemporary literature concerning self-management. Newman’s subdivision of essential components of self-management was used in “giving information”, “behavior change”, “maintaining behavior change”, “enhancing social support”, “managing emotions”, “skills training”, “enhancing communication skills”, and “self-monitoring”.Citation8 Selections of video clips were encoded in accordance with the observation matrix, using the analysis program Dedoose.

Baseline demographic, clinical and contextual measures of the 46 patients and 11 HCPs were obtained by a self-administered questionnaire, including the dyadic PFC.Citation51 Descriptive analyses were used to describe the characteristics of the patients and HCPs, to calculate the mean PFC score per possible confounder, and to provide insight into the percentage of patients and HCPs who were fully satisfied with the consultation. Questions with a score of <90% full satisfaction were used in extra analyses. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to find any covariates that might explain the variance in PFC scores for the patients and HCPs. Dummies were created for employment status. All covariates were recoded into 2 classes, for example age <70 years and age ≥70 years. The mean score on the PFC questionnaire was only calculated if a patient or HCP had answered 10 or more questions out of the 16. All data were analyzed in SPSS version 19.

Feedback phase

The results of the research were shared with participating patients and HCPs in five feedback meetings (two general practices and three outpatient clinics). The responses and comments were integrated into the discussion of the research.

Results

Patient and HCP characteristics

The characteristics of the studied group of patients and observed HCPs consultations are shown in and . A total of 60.9% patients were male, low-educated (50.0%), had an mean age of 70 years, and were mostly of Dutch ethnicity (93.5%). Most of the participating HCPs were women (81.8%) with a mean overall work experience in their profession of 20 years, compared with 9 years specifically in pulmonary medicine.

Table 2 Patients’ social and demographic characteristics (N=46)

Table 3 Health care providers’ social and demographic characteristics

Qualitative results

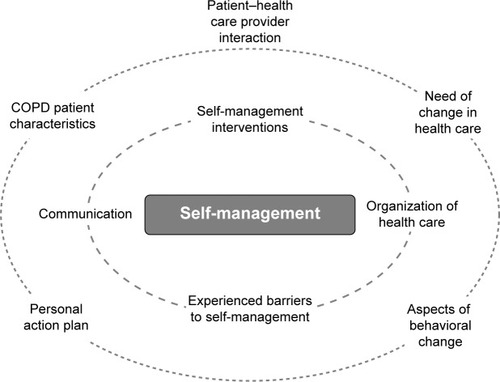

and represent the top 9 most coded key concepts (%; inner circle top 4) analyzed from the interviews with the patients and the HCPs. The most coded concepts in common were “organization of care”, “interventions self-management”, “perceived barriers to self-management”, “patient, caregiver interaction”, “communication”, and “need for change in care”. These concepts were used in developing the observational matrix, together with the essential self-management concepts according to Newman et al.Citation8 After analyzing the consultations using the observation matrix, simultaneous triangulation was applied with the outcome of the analyzed interviews,Citation52 resulting in the following seven main themes.

Use of self-management tools

Both professionals from the primary care and outpatient clinics stated not often using self-management interventions. This corresponds with the observed consultations, revealing no use is made of an individual care plan, e-health application, or any other intervention, though there is a desire among some organizations to apply e-health applications in the nearby future. Although the patients have heard the possibility of using e-health applications, not many actually use it for several reasons. Some patients say they are too old to learn new things. Some have tried but found the confrontation with their disease unpleasant, having to log into the e-health application daily.

Organization of health care

Participating general practices and outpatient clinics had not yet imbedded self-management at the organizational level supported by an integrated approach, such as a COPD program. However, some transmural agreements were made between organizations concerning the referral of patients or the use of a uniform referral form. The majority of the participating organizations had a specialized COPD consultation service in both primary care and outpatient clinics.

Patients did not elaborate much about the organization of health care, but the patients who did were positive about the collaboration between the general practitioner and the pulmonologist.

Consultation structure

The focus of the consultations accentuated on information and knowledge exchange, where controlling and monitoring health-related outcomes were emphasized. We observed no difference between primary care and outpatient clinics, (pulmonary) physicians, nurse practitioners, or community nurses. Aspects of changing lifestyle were discussed thoroughly by nurse practitioners and community nurses, in a lesser extent observed by physicians. The degree of shared decision making is low; the HCPs had a proactive role during consultations. Some HCPs continue their own consultation structure without considering the type of questions patients may have. Others adapt their structure and topics according to the patients’ input.

Patients stress the importance of the HCP giving personal attention in an atmosphere where there is enough time taken for the person beside the disease. Patients indicate that they appreciate the information and advice given during consultation.

Self-management components

Compared to the various essential components of self-managementCitation8 during consultations, much attention is given to the components: “information provision”, “training skills”, and “self-monitoring”. Other components, such as “maintaining behavior change”, “social support”, and “managing emotions” are to a lesser extent raised in the consultation by either the HCP or the patient.

Connecting to patients’ goals and expectations

In 54% of the observed consultations (N=26), HCPs made an inventory of patient-centered goals or asked patients if they had any general questions. The majority of the patients (88.5%) responded not having questions or goals to mention at all. It is one of the reasons HCPs report having difficulties in formulating patient-centered goals with the patients.

Indeed I try with a patient sometimes like […] “Do you have a goal or activity you would like to do, or cannot do anymore for the last five years?” But actually […] it doesn’t work […] because they are quite satisfied with their life now. I think it is pretty difficult! [HCP 0]

Used resources for information transfer

Despite the observed great emphasis on transferring information and knowledge during consultation, little use was made of assistive devices, such as written information, brochures, decision aids, or video materials. The exchange of information between HCPs and patients remains mainly verbal.

Patient-centered communication

Both HCPs and patients express the importance of accessibility and communication on the basis of equality. Connecting with the patients’ social background usually occurred on an intuitive basis. In the interviews, some HCPs expressed experiencing difficulties in estimating what motivated patients to take an active or inactive role in their self-management.

Me searching for the connection with the patient […]is sometimes like a blackbox. [HCP 1]

Where do you find your motivation [as a patient] when you don’t feel related to your disease? [HCP 2]

Also patients explained several difficulties taking the self-management role. After analyzing they were subdivided into three categories:

low level of experienced burden of the disease,

wishing not to be confronted with disease,

dealing with external social problems.

I don’t want to be confronted with my disease constantly. I do not need to know everything about my illness, but prefer the HCP to dose this information when explaining it to me. [Patient 1]

Having a disease […] costs a lot of time. You have to go to the doctor, nurse, dietician, general practitioner […] rehabilitation care […]. At some point you think your whole life is centered around that. [Patient 2]

Quantitative results

provides insight into the response pattern of the patients and HCPs (in %) of the PFC questionnaire, subdivided into the response categories “Completely”, “Mostly”, “A little”, and “Not at all”. It can be seen that the mean score in the highest category “Completely” is much higher among the patients (84.3%) than the mean score of the HCPs (26.5%). Of all patients, 40% (N=20) answered with the maximum score for all questions. Furthermore, 64% of all patients (N=32) had the maximum score and/or did not answer some questions. Further analyses of the patient scores per question item with an mean score of <90% full satisfaction (questions 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 15, and 16) did not significantly explain variance in communication scores (P=0.05; ). In a bivariate model the variance (P=0.09, 0.056, and 0.039) could be explained by the variables duration of illness, gender, and HCPs' experience in lung diseases. However multivariate regression analysis did not show any significant results.

Table 4 Answering pattern and response rate for the patient feedback questionnaire on consultation skills (%)

Discussion and practice implications

The study identified a number of complex underlying mechanisms and determinants at patient, HCP, and organizational levels mutually interacting with each other as described in . These insights yield important conclusions and have significant practice implications which we will discuss.

We can conclude that during consultation a traditional health care approach is still commonly used in which HCPs take the leading role. Despite the great amount of attention paid to lifestyle change and advice during consultation, less emphasis was seen on effective behavioral change and follow-up of the advice given, which is quite understandable given the fact that patients see their HCP once or twice a year. It can be questioned if the low frequency in patient–HCP contact is a good breeding ground for building mutual trust and effectively achieving behavior change.

Earlier research has shown that solely providing information and lifestyle advice are not sufficient enough to actually change lifestyle and behavior.Citation53–Citation55 Emphasis should be placed on connecting to the goals and motivation of the patient using shared decision making.Citation21 From the qualitative data-exploration it can be seen that both patients and HCPs experience difficulties defining personalized goals and expectations. Significant influencing factors are causing this disadvantage. Newman’s self-management component, social support, is little observedCitation8 in the consultations, which relates to the extent social context and participation level in everyday life have been explored. This basic understanding of one’s personal life, daily activity level, motivation, and values is essential to make a personalized plan in improving health, which are in tune with the perceived limitations and possibilities in daily living activities. Verhage et alCitation56 point out the necessity of a detailed patient assessment with the recognition of the diversity of patients in their knowledge and skills, health perception, level of communication, and the motivation to work on their self-management. A customized self-management approach where the patient’s social context, individual background, desires and capabilities are taken into account is lacking.Citation5

Another negatively influencing aspect observed in patient–HCP interaction is the profoundly structured consultation, where explicit attention is given to monitoring and assessment aspects of the COPD. This tendency toward a more rationalized, biomedical medicine, based on protocols and guidelines is a movement which has distinguished itself in the last 15 years.Citation57 The patient–HCP interaction is subsequently changing where the HCP is more proactive, whereas the patient is unwittingly pushed into a more passive role. This is a very contradictory development. Equality between patient and HCP during consultation must be pursued and is most essential in patient-centered communication. Consequently patients feel more uninhibited, which results in them taking a proactive role, sharing their ideas, worries, and questions, and making shared decisions possible.

One success factor seems to be the high satisfaction of the patients with the experienced patient-centered communication during consultation, where a total of 84.3% of the patients (N=46) gave full maximum scores against 26.5% of the HCPs (N=11) answering the PFC. However the high percentage of maximum patient scores made it difficult to measure effects (ceiling effect). While there is no straightforward answer for this observed discrepancy between the perceived patient-centered communication between patient and HCP, one interpretation could be that the HCPs are more critical about themselves concerning their consultation compared with how patients judge this. On one hand, we see satisfied patients with the traditional consultation structure; and on the other hand, we have HCPs indicating having difficulties in formulating patient-orientated goals. We can identify the fact that patients are not yet well accustomed to their new role as a proactive patient, which is also hampered by the overall observed traditional and medically oriented type of consultation structure. Further research is necessary for evaluating the needs of patients regarding self-direction, interaction, and communication with HCPs.

This study has both strengths and limitations. The strength of this study lies in the inclusion of both the patients’ and HCPs’ perspectives gaining insight into the similarities and differences of mutual opinions concerning self-management.

Limitations are the small simple size, which restricted performing subgroup analyses. Patients and HCPs took part in the research on a voluntary basis. It is, therefore, likely that we only reached patients and HCPs who appreciate the importance of supporting self-management. The single recruitment source, via the respiratory community nurse, limited the degree of generalizing the results of the study. No conclusions can be drawn about self-management among various ethnic populations because the majority of the participants had Dutch ethnicity. Finally, we identified high patient scores on the PFC, from which we can conclude patients being very satisfied with the degree of patient-centered communication in the consultation. But giving socially desirable answers to the questions must be considered as another possible explanation.Citation58–Citation60

In summary, although the patient-centered approach being one of the dominant paradigms in modern medicineCitation61–Citation64 our observations accentuate difficulties implementing self-management in daily practice. Both patients and HCPs are still very much framed in a traditional consultation structure according to the biomedical perspective though an observed discrepancy in the satisfaction level of the consultation was seen between patients and their HCPs.

Influencing determinants were identified from the interviews and consultations affecting implementation of self-management at patient, HCP, and organizational level. Seven main themes could be identified: “use of self-management tools”, “organization of care”, “consultation structure”, “self-management components”, “connecting to patients’ goals and expectations”, “used resources for information transfer”, and “patient-centered communication”.

More research is needed of the influencing factors of self-management and for gaining insight into finding the right balance between the implementation of patient-centered medicine in a predominant evidence-based setting. To our knowledge this research was the first study focusing on the interaction between patients and HCPs according to the implementation of self-management, integrating the opinion and perspectives of both, and is a first step in better understanding and unravelling the determinants of self-management.

Acknowledgments

The Patient Empowerment Programme is a cooperative venture between patient organization the Dutch Lung Foundation (Longfonds), the health insurance company Achmea, and AstraZeneca to improve the position of patients with COPD in the care process by means of shared decision making and patient empowerment. We would like to express our warm thanks to the participating patients, the HCPs, and the members of the Patient Empowerment Programme who contributed to the research.

Disclosure

NHC has had temporary consulting roles on the advisory boards of Novartis, Chiesi, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer. OCPvS has received unrestricted research grants from Pfizer and Boehringer Ingelheim. NHC and OCPvS have had temporary consulting roles on the advisory board of the Patient Empowerment Programme. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationWorld health statistics 2008Geneva, SwitzerlandWHO Press2008

- GommerAPoosMCijfers COPD (prevalentie, incidentie en sterfte) uit de VTV 2010. Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid [Data COPD (prevalence, incidence and mortality) from the VTV 2010. Future Public Health Exploration, National Compass Public Health]Bilthoven, the NetherlandsRIVM2010 Dutch

- GijsenROostromSvSchellevisFHoeymansNChronische ziekten en multimorbiditeit samengevatVolksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid [Chronic diseases and multimorbidity summarized, Future Public Health Exploration, National Compass Public Health]Bilthoven, the NetherlandsRIVM2013 Dutch

- BoezenHPostmaDSmitHPoosMHoe vaak komt COPD voor en hoeveel mensen sterven eraan?Volksgezondheid Toekomst Verkenning, Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid. [What is the prevalence and mortality of COPD? Future Public Health Exploration, National Compass Public Health]Bilthoven, the NetherlandsRIVM2006 Dutch

- EffingTWBourbeauJVercoulenJSelf-management programmes for COPD moving forwardChron Respir Dis201291273522308551

- BarlowJWrightCSheasbyJTurnerAHainsworthJSelf-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a reviewPatient Educ Couns200248217718712401421

- HeiligersPJMNoordmanJKorevaarJCKennisvraag: praktijkondersteuners in de huisartspraktijk (POH’s), klaar voor de toekomst? [Knowledge question: Practice-based nurse specialists in the general practice center, ready for the future?]Utrecht, the NetherlandsNIVEL2012124 Dutch

- NewmanSSteedLMulliganKChronic Physical Illness: Self Management and Behavioural InterventionsBerkshire, UKMcGraw-Hill Education2009

- BourbeauJVan der PalenJPromoting effective self-management programmes to improve COPDEur Respir J200933346146319251792

- FeketeEMAntoniMHSchneidermanNPsychosocial and behavioral interventions for chronic medical conditionsCurr Opin Psychiatry200720215215717278914

- Figueroa-MoseleyCJean-PierrePRoscoeJABehavioral interventions in treating anticipatory nausea and vomitingJ Natl Compr Canc Netw200751445017239325

- O’HeaEHousemanJBedekKSposatoRThe use of cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depression for individuals with CHFHeart Fail Rev2009141132018228140

- TazakiMLandlawKBehavioural mechanisms and cognitive-behavioural interventions of somatoform disordersInt Rev Psychiatry2006181677316451883

- ThomasPThomasSHillierCGalvinKBakerRPsychological interventions for multiple sclerosisCochrane Database Syst Rev20061CD004431

- WatersSJMcKeeDCKeefeFJCognitive behavioral approaches to the treatment of painPsychopharmacol Bull20074047488

- BanduraASocial Foundations of Thought and ActionEnglewood Cliffs, NJPrentice-Hall inc1986

- ProchaskaJODiClementeCCVelicerWFRossiJSCriticisms and concerns of the transtheoretical model in light of recent researchBr J Addict19928768258281525523

- ProchaskaJOVelicerWFThe transtheoretical model of health behavior changeAm J Health Promot199712384810170434

- LorigKRHolmanHRSelf-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanismsAnn Behav Med20032611712867348

- OuwensMWollersheimHHermensRHulscherMGrolRIntegrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviewsInt J Qual Health Care200517214114615665066

- ElwynGFroschDThomsonRShared decision making: a model for clinical practiceJ Gen Intern Med201227101361136722618581

- Brink-MuinenAVan DulmenATweede Nationale studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk: oog voor communicatie: huisarts-patiënt communicatie in Nederland [Second national study of diseases and proceedings in general practices: emphasizing communication: doctor-patient communication in the Netherlands]Utrecht, the NetherlandsNIVEL2004 Dutch

- AujoulatId’HooreWDeccacheAPatient empowerment in theory and practice: polysemy or cacophony?Patient Educ Couns2007661132017084059

- SpencerLSpencerPCompetence at work models for superior performanceNew Jersey, NJJohn Wiley and Sons2008

- BourbeauJNaultDDang-TanTSelf-management and behaviour modification in COPDPatient Educ Couns200452327127714998597

- AlpayLLHenkemansOBOttenWRövekampTADumayACE-health applications and services for patient empowerment: directions for best practices in The NetherlandsTelemed J E Health201016778779120815745

- WagnerEHGlasgowREDavisCQuality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approachJt Comm J Qual Improv2001272638011221012

- VrijhoefHJMDutch Chronic Care Model-Model voor geïntegreerde, chronische zorg [Dutch Chronic Care Model for integrated chronic care]SeattleImproving Chronic Illness Care (ICIC)2008 Dutch

- ClineCMJBjörck-LinnéAKIsraelssonBYAWillenheimerRBErhardtLRNon-compliance and knowledge of prescribed medication in elderly patients with heart failureEur J Heart Fail19991214514910937924

- CochraneGMHorneRChanezPCompliance in asthmaRespir Med1999931176376910603624

- GlasgowRECompliance to diabetes regimens: conceptualization, complexity, and determinantsCramerJASpilkerBPatient Compliance in Medical Practice and Clinical TrialsNew York, NYRaven Press1991209224

- KravitzRLHaysRDSherbourneCDRecall of recommendations and adherence to advice among patients with chronic medical conditionsArch Intern Med199315316186918788250648

- PetermanAHCellaDFAdherence Issues Among Cancer Patients. The Handbook of Health Behavior ChangeNew York, NYSpringer Publishing Company1998462482

- HawleyDJWolfeFDepression is not more common in rheumatoid arthritis: a 10-year longitudinal study of 6,153 patients with rheumatic diseaseJ Rheumatol19932012202520318014929

- JuengerJSchellbergDKraemerSHealth related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variablesHeart200287323524111847161

- LehrerPFeldmanJGiardinoNSongHSSchmalingKPsychological aspects of asthmaJ Cons Clin Psychol2002703691

- PincusTGriffithJPearceSIsenbergDPrevalence of self-reported depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritisRheumatol1996359879883

- RubinRRPeyrotMQuality of life and diabetesDiabetes Metab Res Rev199915320521810441043

- VercoulenJHA simple method to enable patient-tailored treatment and to motivate the patient to change behaviourChron Respir Dis20129425926823129804

- EfraimssonEOFossumBEhrenbergALarssonKKlangBUse of motivational interviewing in smoking cessation at nurse-led chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinicsJ Adv Nurs2007684767782

- FinchTMayCMairFMortMGaskLIntegrating service development with evaluation in telehealthcare: an ethnographic studyBMJ200332774251205120914630758

- MayCHarrisonRFinchTMacFarlaneAMairFWallacePUnderstanding the normalization of telemedicine services through qualitative evaluationJ Am Med Inform Assoc200310659660412925553

- TrappenburgJCKoevoetsLde Weert-van OeneGHAction plan to enhance self-management and early detection of exacerbations in COPD patients; a multicenter RCTBMC Pulm Med2009915220040088

- TurnockACWaltersEHWaltersJAWood-BakerRAction plans for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20094CD005074

- BaanDHeijmansMSpreeuwenbergPRijkenMZelfmanagement vanuit het perspectief van mensen met astma of COPD [Self-management from the perspective of patients with Asthma and COPD]Utrecht, the NetherlandsNIVEL2012 Dutch

- NoordmanJKoopmansBKorevaarJCvan der WeijdenTvan DulmenSExploring lifestyle counselling in routine primary care consultations: the professionals’ roleFam Pract201330333234023221102

- WallaceLMTurnerAKosmala-AndersonJEvidence: Co-Creating Health: Evaluation of First PhaseLondon, UKApplied Research Centre in Health and Lifestyle Interventions2012

- LeechNLOnwuegbuzieAJA typology of mixed methods research designsQual Quant2009432265275

- KvaleSDoing InterviewsLondon, UKSage publications2008

- RitchieJSpencerLBrymanABurgessRAnalysing Qualitative DataLondonRoutledge1994

- ReindersMEBlankensteinAHKnolDLde VetHCvan MarwijkHWValidity aspects of the patient feedback questionnaire on consultation skills (PFC), a promising learning instrument in medical educationPatient Educ Couns200976220220619286341

- MorseJMPrinciples of mixed methods and multimethod research designTashakkoriATeddlieCHandbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral ResearchThousands Oaks, CASage2003189208

- CoatesVEBooreJRKnowledge and diabetes self-managementPatient Educ Couns1996291991089006226

- GibsonPPowellHCoughlanJSelf-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthmaCochrane Database Syst Rev20031CD001117

- TaalERaskerJJWiegmanOGroup education for rheumatoid arthritis patientsSemin Arthritis Rheum19972668058169213379

- VerhageTLHeijdraYFMolemaJDaudeyLDekhuijzenPRVercoulenJHAdequate patient characterization in COPD: reasons to go beyond GOLD classificationOpen Respir Med J200931919452033

- BensingJMTrompFVan DulmenSVan den Brink-MuinenAVerheulWSchellevisFDe zakelijke huisarts en de niet-mondige patiënt: veranderingen in communicatie [The businesslike general practitioner and the non-assertive patient: changes in communication]Huisarts en wetenschap2008511612 Dutch

- CampbellCLockyerJLaidlawTMacLeodHAssessment of a matched-pair instrument to examine doctor–patient communication skills in practising doctorsMed Educ200741212312917269944

- GrecoMBrownleaAMcGovernJImpact of patient feedback on the interpersonal skills of general practice registrars: results of a longitudinal studyMed Educ200135874875611489102

- MakoulGKrupatEChangCMeasuring patient views of physician communication skills: development and testing of the communication assessment toolPatient Educ Couns200767333334217574367

- KinnersleyPStottNPetersTJHarveyIThe patient-centredness of consultations and outcome in primary careBr J Gen Pract19994944671171610756612

- MeadNBowerPPatient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literatureSoc Sci Med20005171087111011005395

- StewartMTowards a global definition of patient centred careBMJ2001322728444444511222407

- StewartMPatient-Centered Medicine: Transforming the Clinical MAbingdon, UKRadcliffe Medical Press2003