Abstract

COPD is highly prevalent and associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Clinicians have long been aware that patients with COPD have problems with cognition and are susceptible to mood (depression) and anxiety disorders. With the increasing awareness of COPD as a multisystem disorder, many studies have evaluated the prevalence of neuropsychiatric conditions in patients with COPD. This review presents evidence regarding the prevalence of neuropsychiatric conditions (cognitive disorders/impairment, depression/anxiety) in COPD, their risk factors, and their impact on relevant outcomes. It also discusses both assessment and treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions and makes recommendations for improved screening and treatment. The findings suggest that clinicians caring for patients with COPD must become familiar with diagnosing these comorbid conditions and that future treatment has the potential to impact these patients and thereby improve COPD outcomes.

Introduction

COPD is a highly prevalent condition with substantial attributable morbidity and mortality. In the US, it is estimated that 24 million adults have COPD,Citation1–Citation3 whereas the Canadian Health Measures Survey reports that ~1 million Canadians may have this condition.Citation4 COPD is the third leading cause of death in the USCitation5,Citation6 and the fourth leading cause of death in Canada.Citation4 In developed nations, it is characterized by dyspnea and poorly reversible airflow obstruction caused mostly by cigarette smoking.Citation7 Once thought of as a condition that involved only lungs, COPD is increasingly being associated with comorbidities that have an incidence greater than the general population.Citation8,Citation9 Patients with COPD are more likely to have coronary artery disease,Citation8,Citation10 lung cancer,Citation11,Citation12 metabolic syndrome,Citation13,Citation14 osteoporosis,Citation15,Citation16 diabetes mellitus,Citation8,Citation17 and hypertensionCitation8,Citation18 than persons without COPD, resulting in some suggesting COPD be considered a multisystem inflammatory disorder rather than a condition confined to the lungs.Citation9,Citation19

Clinicians have long been aware that patients with COPD have problems with cognition and are susceptible to mood (depression) and anxiety disorders.Citation20 However, some clinicians may attribute these ailments to the effects of aging and the impact of COPD on patients’ quality of life. With the increasing awareness of COPD as a multisystem disorder and the concern that patients with COPD have underlying pathophysiologic anomalies that may predispose them to other associated conditions,Citation9 many recent studies have investigated whether the prevalence of neuropsychiatric conditions is increased in these patients,Citation21 and whether links exist between neuropsychiatric conditions and COPD severity and outcomes.Citation20 This review summarizes the available information regarding the association of COPD with cognitive and psychiatric disorders.

Classification and definitions

Patients with a cognitive disorder have a mental health problem that affects learning, memory, perception, and/or problem solving.Citation22 Most of these disorders feature damage to areas of the brain concerned with memory.Citation23,Citation24 The main cognitive disorders characterized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)Citation25 are delirium,Citation23 dementia,Citation24 amnesia,Citation26 and mild cognitive impairment (MCI)Citation27 ().

Table 1 Classification of disorders of cognition, mood, and anxiety relevant to COPD

Cognitive disorders range from mild to severe. MCI is defined as impaired cognitive functioning that is greater than expected for a patient’s age and education level but not severe enough to be considered as dementia or interfere with normal daily activities.Citation28,Citation29 Patients with MCI have problems with memory and word findingCitation27 and are at high risk for developing severe cognitive impairment, that is, dementia.Citation30,Citation31 Dementia is more severe than MCI, involves an additional cognitive domain other than memory, and interferes with a person’s ability to carry out routine daily activities.Citation27

Patients with a psychiatric disorder are commonly described as having mood (depression) or anxiety disorders. Mood disorders are characterized by persistent (>2 weeks) negative mood (particularly sadness, hopelessness, and pessimism) accompanied by decreased interest or pleasure in engaging in otherwise pleasurable activities.Citation25 Mood disorders are also associated with sleep and appetite disturbances, significant weight gain or loss (±10%), fatigue, decreased libido, and psychomotor agitation or retardation.

Anxiety disorders are characterized by chronic (>6 months) symptoms of fear, anxiety, and worry that typically lead to persistent avoidance of the feared object (which differs according to the disorder []).Citation25 Somatic symptoms such as sleep disturbances, fatigue, palpitations, breathlessness, and dizziness are also associated with anxiety disorders, but symptoms must be severe enough to cause functional impairment in occupational or social activities for a person to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder.

Patients with COPD are predisposed to both cognitive and psychiatric disorders.Citation9 The available information regarding links between these disorders and COPD severity and outcomes is summarized in the following sections.

Cognitive disorders

Occurrence of cognitive disorders in COPD

Prevalence

Most of the studies demonstrate an increased occurrence of cognitive disorders in patients with COPD.Citation21 Antonelli-Incalzi et al described a high prevalence of cognitive dysfunction by a mini-mental state examination (MMSE) among 32.8% of 149 patients with severe COPD, albeit in a small patient cohort with no comparator group included.Citation32 These authors previously characterized the neuropsychiatric profile of a small cohort of patients with hypoxic-hypercapnic COPD (n=36) by comparing their cognitive domain test scores to a control group (healthy adults, healthy elderly adults, Alzheimer patients, and multi-infarct dementia patients). Discriminant analysis of the test scores classified the COPD patients as cognitively impaired (49%), healthy elderly adults (15%), healthy adults (12%), adults with Alzheimer-type dementia (12%), or adults with multi-infarct dementia (12%). The COPD patients classified as cognitively impaired had a specific pattern of findings characterized by deficits in verbal skills and verbal memory but preserved visual attention.

In a large US longitudinal health survey, Martinez et al reported that 9.5% of 17,535 participants (≥53 years of age) reported COPD, and 17.5% of those had MCI, which was significantly higher compared with all respondents (13.1%, P=0.001).Citation33 They estimated that 1.3 million US adults have both COPD and cognitive impairment. Villeneuve et al identified MCI in 36% of COPD patients (n=45) compared with 12% in the healthy controls (n=50).Citation34 Other studies have also confirmed a high prevalence of cognitive impairment in patients with COPD.Citation35,Citation36 Also, dementia is a frequent diagnosis in patients with COPD. Studying a Taiwan national health database, Liao et al found that the hazard ratio for the development of dementia in COPD patients was 1.74 compared with patients without COPD after adjusting for age, gender, and comorbidities.Citation37 In contrast, a few studies suggest that the prevalence of cognitive deficits may not be higher in patients with COPDCitation38–Citation40 or that cognitive deficits are confined to those patients with COPD who have chronic hypoxemia.Citation39 However, others have found that even nonhypoxemic COPD patients do have cognitive deficits.Citation41

Risk factors

Multiple risk factors are associated with the development of cognitive impairment in COPD patients. Using data from the Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Aging and Dementia study (n=2,000), Rusanen et al found that midlife COPD conferred a 1.85-fold risk of cognitive impairment later in life (after controlling for other measured factors).Citation42 Similarly, COPD was significantly associated with the risk of developing cognitive impairment in the Mayo Clinic Study on Aging (hazard ratio 1.83; n=1,425).Citation43 In addition, Tulek et al examined cognition in mostly male patients with COPD (n=119) and determined that the frequency of COPD exacerbations was inversely associated with cognition, potentially implicating exacerbation severity in the development of cognitive impairment.Citation44 Etnier et al found that age and aerobic fitness were also associated with cognitive performance in COPD patients,Citation45 whereas another study observed that very elderly (≥75 years of age) men with COPD have a particularly rapid decline in cognitive function,Citation46 suggesting that COPD is a significant risk factor for cognitive decline in older patients. In general, the risk factors for the development of cognitive impairment in COPD may be associated with chronic hypoxia–hypercapnia, which has been reported to correlate with cognitive deficits in patients with COPD.Citation47,Citation48

Assessment

The use of multiple diagnostic tests may improve the detection of cognitive deficits. Antonelli-Incalzi et al demonstrated that the combination of the MMSE with the instrumental activities of daily living tool had better diagnostic accuracy for cognitive deficits in COPD than either instrument alone.Citation49 Other diagnostic tests that have demonstrated utility include the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test,Citation50 the Trail Making Test, tactual performance tests, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, immediate and delayed verbal and nonverbal memory tests,Citation51,Citation52 and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale.Citation53 Furthermore, electroencephalography utilizing both auditory and visual P300-evoked responses has revealed that progressive impairment of the auditory (but not visual) P300 reaction time occurs with increasing severity of COPD.Citation54,Citation55

Mechanisms linking cognitive impairment to COPD

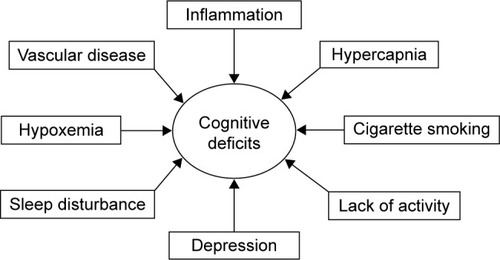

Patients with COPD have cognitive deficits that seem to correlate with the degree of hypoxemia. Abnormalities are not limited to neuropsychological testing, as these patients have structural and functional brain abnormalities as well. Postulated mechanisms for cognitive deficits and structural and functional brain abnormalities in COPD may involve hypoxemia,Citation47,Citation48 hypercapnia,Citation48,Citation56 cigarette smoking,Citation57 inflammation,Citation58 vascular disease,Citation8,Citation59 sleep disturbance,Citation60 lack of activity,Citation45 and depressionCitation61 (), though it is unlikely that any one of these mechanisms is sufficient to explain cognitive impairment in COPD. For example, prevalence of depression in COPD ranges from 10%–79% but accounts for only 1%–2% of the variance in cognition in these patients.Citation20 In addition, COPD patients with coexistent vascular diseaseCitation62 have a different pattern of cognitive dysfunction compared with those with vascular dementia,Citation56 and memory has been shown to be worse in subjects with cerebrovascular disease than in those with COPD.Citation38 Thus, although a number of mechanisms seem to be associated with cognitive impairment, it remains unproven that these mechanisms entirely account for the cognitive deficits observed in patients with COPD.

Figure 1 Contributing factors to cognitive deficits in patients with COPD.a

Many studies support the hypothesis that cognitive deficits in COPD are the result of hypoxemia. A study in patients with asthma or COPD (n=40) demonstrated a direct correlation between low oxygen saturation and poor performance on certain tests of cognition.Citation63 In a larger controlled study (n=1,202) of patients with COPD, Thakur et al found an association between low oxygen saturation and cognitive impairment as determined by the MMSE (odds ratio [OR] 5.45 for patients with oxygen saturation <88%), as well as a reduced risk for cognitive impairment in patients receiving supplemental oxygen (OR 0.14).Citation64 These studies, as well as those previously cited,Citation32,Citation56 suggest a relationship between hypoxemia and cognitive deficits in patients with COPD.

Data from imaging studies also suggest a relationship between hypoxemia and cognitive deficits in patients with COPD. A single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) study showed that patients with hypoxemic COPD had evidence of hypoperfusion in the anterior cortical and subcortical regions of the brain compared with healthy control subjects and COPD patients without hypoxemia.Citation65 Furthermore, the degree of hypoperfusion correlated with the degree of neuropsychological dysfunction. A similar SPECT study demonstrated decreased cerebral perfusion, with the degree of decrement correlating with the degree of cognitive deficits.Citation47 Moreover, although all COPD patients had impaired verbal memory, hypoxemic COPD patients had lower recall and attention scores compared to nonhypoxemic patients.

Li and Fei used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess hippocampal volume, an indicator of cognitive performance.Citation66 COPD patients had smaller hippocampal volume than normal controls. However, the hippocampal volume was not different between patients with mild to moderate COPD and those with severe COPD. Dodd et al extended these results in nonhypoxemic COPD patients using advanced MRI techniques and identified substantial reductions in both white matter integrity and gray matter functional activation, which corresponded to cognitive dysfunction.Citation67

Clinical outcomes in patients with COPD and cognitive deficits

Patients with COPD who have cognitive deficits suffer from adverse health care outcomes. Martinez et al studied the development of disability in a large COPD population.Citation33 The data, captured in the Health and Retirement Study, defined disability as dependency in one or more activities of daily living. Martinez et al reported that prevalent disability was present at baseline in 12.8% of the COPD population compared with 5.2% in the non-COPD population (P<0.001) and that incident disability during 2 years of follow-up was 9.2% in the COPD population compared with 4.0% in the non-COPD population (P<0.001). Of note, the presence of cognitive impairment in the patients with COPD had an additive effect on prevalent and incident disability. Together, these data suggest that COPD and cognitive impairment increase the risk of disability.

In patients hospitalized with an acute COPD exacerbation, impaired cognitive function is associated with worse health status and longer hospital length of stay.Citation68 In addition, patients with cognitive decline and COPD may be at greater risk of hospitalization for respiratory problems. The Cardiovascular Health Study involved 3,093 patients >65 years of age; 431 had COPD.Citation69 Patients who had both COPD and cognitive decline had the highest rate of hospitalization for respiratory problems, the highest all-cause hospitalization rate, and the highest death rate compared with other patients. Furthermore, patients with both conditions had a 48% increase in the risk of all-cause hospitalization and three times the risk of death than would have been predicted by the sum of the independent risks from either condition alone. However, statistical tests for interaction were not significant, so that synergy was unconfirmed.

Hospitalization for respiratory problems may be associated with a subsequent decline in cognitive function. Ambrosino et al studied 63 patients hospitalized for an exacerbation of COPD that required mechanical ventilation and found that patients’ cognitive status was significantly worse at discharge (according to the MMSE) compared with controls.Citation70 Likewise, patients discharged after a COPD exacerbation had significantly worse cognitive function than stable outpatients with COPD;Citation68 57% of patients discharged after a COPD exacerbation were considered impaired and 20% had pathologic impairment. Whether the patients in these studies had undetected cognitive impairment that preceded the exacerbation or whether cognitive impairment developed because of the exacerbation is unclear. Similar findings have been reported by other groups.Citation21,Citation71

Preliminary data suggest that patients with both COPD and cognitive decline may have increased mortality. Fix et al reported that poor performance on cognitive testing in COPD patients was associated with increased mortality;Citation72 patients who later died had scored significantly (P<0.01) lower on neuropsychological tests than those who had survived. In patients with hypoxemic COPD, Antonelli-Incalzi et al demonstrated that while distance walked in 6 min and drawing impairment (landmark test) were risk factors for mortality, other factors such as partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, comorbid diseases, and the impairment of cognitive domains other than drawing were unrelated to the outcome.Citation32

Treatment for patients with COPD and cognitive disorders

Limited evidence exists to show that, in patients with COPD and cognitive disorders, improved cognition is associated with improved clinical outcomes such as exacerbation rate, compliance with medication, hospitalization, or quality of life. Treatments including oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), telemedicine, and pharmacologic therapy seem to be efficacious in small cohorts of patients;Citation73–Citation78 however, prospective longitudinal studies evaluating associations between cognitive improvements in other COPD outcomes in large diverse populations of COPD patients are lacking.

Oxygen therapy is an established treatment for cognitive deficits and COPD that attempts to reverse the putative effects of hypoxemia on the central nervous system. More than 40 years ago, Block et al demonstrated improvements in cognitive testing in 12 patients with severe hypoxemic COPD after 1 month of treatment with supplemental oxygen.Citation79 In a landmark article that compared continuous oxygen therapy to nocturnal oxygen therapy in patients with COPD, researchers for the Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial (NOTT) noted that continuous oxygen therapy was associated with a lower mortality than nocturnal oxygen therapy.Citation73 The reason for this difference was not clear, but follow-up of a cohort of the NOTT patients demonstrated that patients who received continuous oxygen therapy had improved cognitive status.Citation80 In addition, Hjalmarsen et al studied a small cohort of patients treated with continuous oxygen therapy for 3 months and found trends for improvement in neuropsychological functioning and cerebral blood flow compared with age-matched healthy controls.Citation74

As previously noted, Thakur et al demonstrated that the use of continuous supplemental oxygen reduced the risk of cognitive impairment.Citation64 It is noteworthy that the Thakur study was an observational study that examined oxygen use as a risk factor for cognitive deficits and was not a prospective treatment trial. In contrast, Dal Negro et al compared 73 patients with COPD who received continuous oxygen treatment with 73 patients with COPD who received oxygen “as needed.”Citation81 Based on a battery of four tests, those patients who received continuous oxygen demonstrated improved cognition, but the findings are limited because the nonrandomized study allowed patients to self-select their oxygen treatment option. Although long-term oxygen treatment may benefit cognitive deficits in hypoxemic COPD patients, short-term use seems to be ineffective. Pretto and McDonald, for example, reported that acute oxygen use failed to improve simulated driving performance or neurocognitive function in a small group of hypoxemic COPD patients.Citation82

PR, which comprises individualized exercise programs and education for patients with chronic respiratory impairment,Citation83 has been proposed as a treatment to improve cognition in patients with COPD, since diminished aerobic fitness is a proven risk factor for cognitive impairment in these patients.Citation45 Kozora and Make examined the effects of a 3-week PR treatment program in 30 COPD patients.Citation75 Patients enrolled in the PR program demonstrated improved cognition (P<0.05) as well as increased exercise capacity compared to untreated COPD patients and healthy control subjects. Emery et al studied 79 patients with COPD whom they randomized to exercise, education, and stress management; education and stress management without exercise; or a waiting list.Citation84 Patients in the exercise arm demonstrated increased verbal fluency but no improvement in tests of attention and motor speed compared with patients either not assigned to education and stress management or on a waiting list.

Etnier and Berry examined a group of 40 patients with COPD who initially entered a 3-month exercise program.Citation85 Cognitive functioning improved after this program. Subsequently, they split the group into a cohort that continued in the exercise program for 15 months and a cohort that discontinued the program. Cognitive function was not different between the long-term cohort and the terminated cohort, suggesting that short-term exercise may be sufficient to realize sustained cognitive benefits in patients with COPD. This contrasts with findings of Emery et al who followed patients for 1 year after completion of a 10-week exercise program.Citation86 The 39% of patients who continued to exercise maintained their cognitive improvements, whereas the patients who discontinued exercise experienced a decline in cognition. These authors subsequently investigated the effects of a single exercise session on cognition, comparing 29 COPD patients with 29 matched healthy controls.Citation76 A single exercise session improved the COPD patients’ performance on a verbal fluency test. The general association between exercise and improved outcomes in COPD is likely multifactorial, but improved aerobic capacity, increased ability to accomplish tasks of daily living, and improved mood may be involved.

Investigators have also explored telemedicine (eg, delivery of COPD education or coping skills training by phone or computerCitation87) as a potential treatment for cognitively impaired patients with COPD. In the Virtual Hospital Trial in Denmark, the effect of telemedicine on cognition following a COPD exacerbation was studied.Citation77 After screening 647 patients admitted to an emergency department, 58 were eligible for the study based on a diagnosis of COPD exacerbation. Eligible patients were randomized into two groups: treatment via hospitalization (n=22) and treatment at home using telemedicine (n=22). The results of a battery of cognitive tests showed no significant difference in cognition between the groups, suggesting patients with exacerbations were able to manage the telemedicine-based treatment despite the reduced cognitive function often observed in COPD patients.

Limited data exist concerning the impact of pharmacological therapies on either cognitive disorders or psychological conditions in COPD patients. In a mouse model of Down syndrome, the administration of formoterol, a long-acting beta-2 agonist used to treat COPD, improved synaptic density and cognitive function.Citation88 A study in a rodent model demonstrated that roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor indicated for the treatment of COPD, may be associated with improved cognition.Citation89 Definitive studies associating specific pharmacologic treatments for COPD with improved cognitive or psychological outcomes in patients with COPD do not exist. Interestingly, in a cohort of elderly asthma patients, improved asthma control was associated with improved cognitive function;Citation78 however, these findings were not confirmed in a population of elderly urban dwellers with asthma (or with COPD).Citation90 Further research is needed.

Cognitive impairment may negatively affect pharmacologic treatment outcomes in patients with COPD. For example, COPD patients with cognitive impairment may have difficulty utilizing hand-held device formulations of respiratory medications (eg, dry powder inhalers [DPIs], pressurized metered-dose inhalers), resulting in insufficient dosing that jeopardizes health outcomes, reduces quality of life, and further adds to the economic burden of COPD.Citation91–Citation93 Furthermore, cognitive impairment may make it difficult for patients to synchronize inhalation with activation,Citation94,Citation95 or patients may be unable to generate a sufficient inspiratory flow rate against the resistance of a breath-activated DPI to generate an effective aerosol.Citation92,Citation93,Citation96–Citation98 In contrast, compared with hand-held devices, nebulizers require minimal cognitive ability and do not require hand-breath coordination, manual dexterity, or hand strength.Citation96 Regardless of delivery device selection, however, pharmacological therapy in COPD patients with cognitive impairment should include training on correct use of the device as well as follow-up to ensure technique and treatment adherence.

The possible association of adverse health-related outcomes in patients with COPD and cognitive impairment merits further study. Should such an association be demonstrated, both adverse health-related outcomes and cognitive impairment could be the result of the underlying pathophysiology of COPD, now commonly viewed as a systemic disease. The mechanism by which cognitive impairment leads to adverse outcomes in COPD patients would need to be further elucidated. The authors speculate that the inability of patients to follow treatment regimens and maintain medical follow-up may play an important role.

Psychiatric disorders

In addition to cognitive disorders, patients with COPD are susceptible to psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety ().Citation9,Citation99 The occurrence of psychiatric disorders in COPD and the clinical outcomes in patients with COPD and psychiatric disorders are summarized in the following sections.

Occurrence of psychiatric disorders in COPD

Prevalence

High rates of depression and anxiety, at both clinical and subclinical levels, have been observed in patients with COPD,Citation100 with 6%–80% of patients suffering from anxiety and depressive symptoms and up to 55% suffering from anxiety and mood disordersCitation101 (ie, distress at a level that interferes with daily functioning). The detection of high levels of psychological distress and the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders may be challenging in patients with COPD due to a number of factors: 1) the failure of patients and health care providers to recognize symptoms of anxiety or depression as psychological distress rather than symptoms of COPD, 2) the perception that depression and anxiety are “normal” reactions to having an incurable chronic disease rather than a marker of poor psychosocial adjustment, 3) fewer opportunities to detect distress due to the increased avoidance and social isolation that often accompanies COPD, and 4) the lack of systematic screening for psychological distress as part of routine care.Citation102,Citation103 It has been reported that primary care physicians fail to diagnose depression in more than half of depressed patients, which indicates a critical need to improve both the recognition and treatment of psychological distress among COPD patients.Citation104

Risk factors

The precise causes of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD are not known; however, they are likely due to a complex interaction between physiological, behavioral, and psychosocial factors.Citation99,Citation105 Cigarette smoking has long been recognized as the primary cause of COPD in developed countries,Citation2,Citation106 and individuals with psychiatric comorbidities are twice as likely to be cigarette smokers relative to those without psychiatric comorbidities,Citation107 suggesting that psychiatric morbidity could precede the development of COPD.

Other risk factors for the development of depression and anxiety involve poor psychosocial adaptation to having COPD. For example, the chronic and progressive nature of COPD, characterized by frequent episodes of acute exacerbations that often lead to hospital admissions, may cause anxiety, hopelessness, helplessness, and depressed mood. In a population-based sample of those with and without COPD (n=476), Lu et alCitation108 found that stress related to decreased energy, anxiety, and fear/panic in response to breathing difficulties was associated with increased depressive symptoms and impaired quality of life among patients with COPD compared to age-matched controls. Excessive dyspnea experienced at rest and/or during physical exertion that is not relieved by medication may also be traumatic for some and lead to increased anxiety and somatic hypervigilance.Citation109 Teixeira et alCitation109 examined the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in patients with COPD and reported that one-third of patients met criteria for PTSD. Finally, the fact that COPD is typically diagnosed later in life, when patients are more likely to experience age-related losses (retirement, death of loved ones, diminishing social networks), may increase feelings of loneliness and may also trigger symptoms of depression and anxiety.Citation110

Assessment

Because of significant overlap of certain symptoms of depression and anxiety (eg, low mood, loss of interest, decreased energy) with those of COPD (eg, fatigue, sleep disturbance, loss of ability to engage in pleasurable activities),Citation111 it is important to assess psychological distress using validated questionnaires and/or interviews. Some of the most common symptom questionnaires include the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,Citation112 the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory.Citation113,Citation114 Mood and anxiety disorders should be assessed by a structured interview that uses diagnostic criteria (ie, DSMCitation25). Interviews include the Structured Clinical Interview for DSMCitation115 and the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM.Citation116 If time and resource limitations preclude the administration of a formal interview, shorter semistructured screening interviews are also available, such as the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD).Citation117 The PRIME-MD questionnaire was designed to detect the most common DSM disorders that present in primary and tertiary care settings. It uses diagnostic algorithms to generate diagnoses based on DSM criteria that exhibit comparable reliability, sensitivity, and specificity to longer structured psychological interviews.Citation117 The questionnaire takes between 10 and 15 min to administer and score and has been used extensively to assess psychiatric disorders in chronic disease populations.Citation118–Citation120

Clinical outcomes in patients with COPD and psychiatric disorders

Several negative consequences are associated with untreated depression and anxiety among COPD patients. Numerous studies have shown that COPD patients with comorbid depression and anxiety are at greater risk of having exacerbations and have higher rates of emergency visits and hospitalizations (and when hospitalized, have longer lengths of stay). COPD patients with comorbid depression and anxiety also exhibit greater symptom burden, increased disability, and poorer social functioning than do patients with COPD alone.Citation121–Citation124 Finally, evidence suggests that depression may be a risk factor for mortality among COPD patients. A recent systematic review of long-term follow-up studies found that the presence of depression among COPD patients increased their risk of death by 83%, particularly among men.Citation125 The review also revealed that depression had a greater impact on mortality risk among COPD patients relative to those with other chronic diseases such as heart and kidney disease and cancer, suggesting that depression may be particularly detrimental to COPD survival.

Mechanisms linking psychiatric disorders to worse COPD outcomes

Although the exact reasons for worse outcomes in COPD patients with psychiatric comorbidity remain unclear, evidence suggests that they may be related to poorer health behaviors and worse disease self-management. Depression and anxiety are associated with feelings of helplessness, withdrawal, hopelessness, and fear, which may lower confidence in patients’ ability to self-manage their disease. COPD patients with depression have been shown to have worse adherence to medical treatmentCitation101,Citation111,Citation123,Citation124 and are more likely to be persistent smokersCitation108,Citation109 relative to nondepressed patients.Citation121,Citation122 Depression and anxiety are also associated with impaired cognitive function (distorted thoughts and beliefs) that could lead patients to misinterpret symptoms such as breathlessness, leading to over-reporting and increases in health care and medication use.Citation126

Finally, depression and anxiety could worsen COPD outcomes through various psychophysiological pathways, including autonomic nervous system and immune dysregulation.Citation127 It has been well documented that chronic stress can lead to persistent activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and an increased risk for the development of cardiovascular disease.Citation128 This persistent activation of the SNS may also increase the risk for exacerbations in COPD patients via autonomic pathways. With regard to immune mechanisms, Cohen et al have shown that individuals who experience chronic stress are at higher risk of infection when exposed to viral and bacterial infections such as the common cold.Citation129,Citation130 This suggests that COPD patients experiencing chronic depression and/or anxiety may have compromised immune responses, leading to an increased risk of exacerbations in this highly vulnerable population.Citation131,Citation132

Taken together, research to date indicates that COPD patients with comorbid depression and anxiety may have a higher symptom burden and worse outcomes. This may be the result of poorer self-management, cognitive factors, or psychophysiological mechanisms, pointing to a need to improve detection and treatment of psychiatric disorders in patients with COPD.

Treating patients with COPD and psychiatric disorders

Several treatment options exist for COPD patients suffering from anxiety and/or depression, including psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and exercise within the context of a comprehensive PR program. Similar to patients with COPD and cognitive disorders, however, limited evidence exists that treatment of psychiatric disorders in patients with COPD is associated with improved COPD outcomes, and prospective longitudinal studies evaluating such associations in large diverse populations of COPD patients are lacking.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is regarded as a first line of psychotherapy for older patients with mild to moderate depression depending on availability and patients’ preference.Citation133 It focuses on identifying and reframing negative, dysfunctional thoughts while participating in pleasurable and social activities. Hynninen et alCitation134 conducted a randomized, controlled trial that compared 8 weeks of CBT (n=25) to enhanced standard care (n=26) in COPD patients with comorbid depression. CBT resulted in improvement in symptoms of anxiety and depression compared with the enhanced standard care group, with improvements maintained at 8 months. Farver-Vestergaard et alCitation135 reported that CBT was superior to usual care in improving psychological well-being (depression) in patients with COPD (P<0.04). However, a similar review reported a nonsignificant trend in favor of CBT over usual care for the reduction of anxiety and depression in COPD patients.Citation136 Although mixed, the literature indicates that CBT is likely effective for reducing anxiety and depression among COPD patients.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline for the management of depression and anxiety in older people recommends the use of antidepressants in patients with moderate to severe physical illness, including COPD.Citation133 It suggests the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as a first-line treatment of depression or anxiety (due to their better safety record compared with tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs]). However, a recent systematic review examined the efficacy of both SSRIs and TCAs in patients with COPD and found inconclusive evidence in clinical trials.Citation137 The trials were small, and depressed COPD patients had poor adherence to treatment, were often unwilling to accept antidepressant prescriptions, and had a high dropout rate due to intolerance of side effects. To date, it remains unclear whether antidepressants can induce remission of depression or improve symptoms or physiological indices of COPD.Citation137 Therefore, well-controlled clinical trials are required to examine the efficacy of SSRIs in depressed and anxious COPD patients.

Finally, exercise treatment as part of a comprehensive PR program (individualized exercise and education) has also demonstrated reductions in levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms among COPD patients when compared with usual care.Citation138,Citation139 For example, a recent noncontrolled intensive 3-week outpatient PR program (6 h per day, 5 days per week) showed significant improvements in depression and anxiety in patients with COPD.Citation140 Although exercise has been shown to reduce psychological distress in the short term (ie, 12 weeks), the long-term benefits of exercise in reducing anxiety and depression in patients with COPD are unknown. Further work is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of exercise on psychological distress levels among COPD patients.

In summary, depression and anxiety (both symptoms and clinical disorders) are prevalent among COPD patients and are associated with worse outcomes, including higher exacerbation rates, greater functional limitations, and increased mortality. This may be the result of poorer self-management, cognitive factors, or psychophysiological mechanisms. Smoking is a common feature of both COPD and psychiatric disorders and may be a common risk factor. Treatments including CBT, antidepressants, and exercise in the context of PR all show promise for treating depression and anxiety in COPD patients.

Summary and conclusion

Patients with COPD suffer from various comorbidities that many in the scientific community now view as constitutive elements of the disease. Prominent among these are cognitive and psychiatric disorders, both of which implicate important health care outcomes for these patients. Preliminary research suggests that some pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions have the potential to ameliorate the negative health care outcomes associated with cognitive and/or psychiatric disorders, but definitive data do not yet exist. Clinicians caring for these patients must become familiar with tools to screen for these associated conditions. In the future, treatments may become available that will not only modify the course of these neuropsychological disorders but also potentially modify the critical outcomes of COPD.

Acknowledgments

Manuscript editing support was provided by Mylan Pharmaceuticals (Canonsburg, PA). Roger J Hill, PhD of Ashfield Healthcare Communications (Middletown, CT) reviewed and revised the manuscript with input from the authors, and Paula Stuckart of Ashfield Healthcare Communications copyedited and styled the manuscript per journal requirements.

Disclosure

Salary support was provided by Investigator Awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Fonds de la Recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS) (Lavoie). The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ManninoDMHomaDMAkinbamiLJFordESReddSCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance: United States, 1971–2000MMWR Surveill Summ200251116

- PauwelsRARabeKFBurden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Lancet2004364943461362015313363

- National Heart Lung, and Blood InstituteData fact sheetChronic obstructive pulmonary disease Available from: http://www.apsfa.org/docs/copd_fact.pdfAccessed June 6, 2016

- Public Health Agency of CanadaChronic Pulmonary Obstructive Disease (COPD)OttawaPublic Health Agency of Canada Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.Gc.ca/cd-mc/publications/copd-mpoc/ff-rr-2011-eng.phpAccessed March 24, 2016

- Cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health StatisticsData brief 63: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998–2009 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db63_tables.pdf#2Accessed March 4, 2016

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The health benefits of smoking cessationU.S. Department of Health and Human Services, public health service, centers for disease control, center for chronic disease prevention and health promotion, office on smoking and healthDHHS publication no. (CDC) 90-84161990 Available from: https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/NN/B/B/C/T/Accessed June 6, 2016

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- ManninoDMThornDSwensenAHolguinFPrevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPDEur Respir J200832496296918579551

- FabbriLMLuppiFBegheBRabeKFComplex chronic comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J200831120421218166598

- SidneySSorelMQuesenberryCPJrDeLuiseCLanesSEisnerMDCOPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser permanente medical care programChest200512842068207516236856

- BrodyJSSpiraAState of the art. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammation, and lung cancerProc Am Thorac Soc20063653553716921139

- YoungRPHopkinsRJChristmasTBlackPNMetcalfPGambleGDCOPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking historyEur Respir J200934238038619196816

- MarquisKMaltaisFDuguayVThe metabolic syndrome in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil2005254226232 discussion 233–23416056071

- WatzHWaschkiBKirstenAThe metabolic syndrome in patients with chronic bronchitis and COPD: frequency and associated consequences for systemic inflammation and physical inactivityChest200913641039104619542257

- BiskobingDMCOPD and osteoporosisChest2002121260962011834678

- FergusonGTCalverleyPMAndersonJAPrevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the towards a revolution in COPD health studyChest200913661456146519581353

- ParappilADepczynskiBCollettPMarksGBEffect of comorbid diabetes on length of stay and risk of death in patients admitted with acute exacerbations of COPDRespirology201015691892220546185

- BarrRGCelliBRManninoDMComorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPDAm J Med2009122434835519332230

- AndersonDMacneeWTargeted treatment in COPD: a multi-system approach for a multi-system diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009432133519750192

- DoddJWGetovSVJonesPWCognitive function in COPDEur Respir J201035491392220356988

- SchouLOstergaardBRasmussenLSRydahl-HansenSPhanarethKCognitive dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a systematic reviewRespir Med201210681071108122579108

- GuerreroAPiaseckiMProblem-Based Behavioral Science and PsychiatryNew York, NYSpringer2008

- TorpyJMBurkeAEGlassRMJama patient page. DeliriumJAMA2010304781420716747

- TorpyJMLynmCGlassRMJama patient page. DementiaJAMA200830019233019017921

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®)2013 Available from: https://goo.gl/X6zEGJAccessed July 22, 2016

- SchacterDLMemory, amnesia, and frontal lobe dysfunctionPsychobiology19871512136

- TorpyJMLynmCGlassRMJama patient page. Mild cognitive impairmentJAMA200830013161018827219

- FeldmanHHJacovaCMild cognitive impairmentAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200513864565516085780

- GauthierSReisbergBZaudigMMild cognitive impairmentLancet200636795181262127016631882

- PetersenRCStevensJCGanguliMTangalosEGCummingsJLDeKoskySTPractice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology20015691133114211342677

- BruscoliMLovestoneSIs MCI really just early dementia? A systematic review of conversion studiesInt Psychogeriat2004162129140

- Antonelli-IncalziRCorsonelloAPedoneCDrawing impairment predicts mortality in severe COPDChest200613061687169417166983

- MartinezCHRichardsonCRHanMKCigolleCTChronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cognitive impairment, and development of disability: the health and retirement studyAnn Am Thorac Soc20141191362137025285360

- VilleneuveSPepinVRahayelSMild cognitive impairment in moderate to severe COPD: a preliminary studyChest201214261516152323364388

- OzgeCOzgeAUnalOCognitive and functional deterioration in patients with severe COPDBehav Neurol200617212113016873924

- Dal NegroRWBonadimanLTognellaSBricoloFPTurcoPExtent and prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic non-obstructive bronchitis, and in asymptomatic smokers, compared to normal reference valuesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014967568325061286

- LiaoKMHoCHKoSCLiCYIncreased risk of dementia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMedicine (Baltimore)20159423e93026061317

- FioravantiMNaccaDAmatiSBuckleyAEBisettiAChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated patterns of memory declineDementia19956139487728218

- IncalzilRABelliaVMaggiSMild to moderate chronic airways disease does not carry an excess risk of cognitive dysfunctionAging Clin Exp Res200214539540112602575

- IsoahoRPuolijokiHHuhtiELaippalaPKivelaSLChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment in the elderlyInt Psychogeriatr199681113125

- LieskerJJPostmaDSBeukemaRJCognitive performance in patients with COPDRespir Med200498435135615072176

- RusanenMNganduTLaatikainenTTuomilehtoJSoininenHKivipeltoMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma and the risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a population based CAIDE studyCurr Alzheimer Res201310554955523566344

- SinghBMielkeMMParsaikAKA prospective study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk for mild cognitive impairmentJAMA Neurol201471558158824637951

- TulekBAtalayNBYildirimGKanatFSuerdemMCognitive function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: relationship to global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2011 categoriesRespirology201419687388024935516

- EtnierJJohnstonRDagenbachDPollardRJRejeskiWJBerryMThe relationships among pulmonary function, aerobic fitness, and cognitive functioning in older COPD patientsChest1999116495396010531159

- ZhouGLiuJSunFAssociation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with cognitive decline in very elderly menDement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra2012221922822719748

- OrtapamukHNaldokenSBrain perfusion abnormalities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: comparison with cognitive impairmentAnn Nucl Med20062029910616615418

- ZhengGQWangYWangXTChronic hypoxia-hypercapnia influences cognitive function: a possible new model of cognitive dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Hypotheses200871111111318331781

- Antonelli-IncalziRCorsonelloATrojanoLScreening of cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseDement Geriatr Cogn Disord200723426427017351318

- CrisanAFOanceaCTimarBFira-MladinescuOCrisanATudoracheVCognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePLoS One201497e10246825033379

- ParkSKLarsonJLCognitive function as measured by trail making test in patients with COPDWest J Nurs Res201537223625624733234

- PrigatanoGPParsonsOWrightELevinDCHawrylukGNeuropsychological test performance in mildly hypoxemic patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Consult Clin Psychol19835111081166826857

- VermaNBeretvasSNPascualBMasdeuJCMarkeyMKAlzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging InitiativeNew scoring methodology improves the sensitivity of the Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) in clinical trialsAlzheimers Res Ther20157111726584966

- KirkilGTugTOzelEBulutSTekatasAMuzMHThe evaluation of cognitive functions with p300 test for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in attack and stable periodClin Neurol Neurosurg2007109755356017532116

- ReevesRRStruveFAPatrickGPayneDKThirstrupLLAuditory and visual p300 cognitive evoked responses in patients with COPD: relationship to degree of pulmonary impairmentClin Electroencephalogr199930312212510578477

- IncalziRAGemmaAMarraCMuzzolonRCapparellaOCarboninPChronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An original model of cognitive declineAm Rev Respir Dis199314824184248342906

- OttAAndersenKDeweyMEEffect of smoking on global cognitive function in nondemented elderlyNeurology200462692092415037693

- BorsonSScanlanJFriedmanSModeling the impact of COPD on the brainInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083342943418990971

- LahousseLTiemeierHIkramMABrusselleGGChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cerebrovascular disease: a comprehensive reviewRespir Med2015109111371138026342840

- UrbanoFMohseninVChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sleep: the interactionPanminerva Med200648422323017215794

- van EdeLYzermansCJBrouwerHJPrevalence of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewThorax199954868869210413720

- Report of the national chronic obstructive pulmonary disease audit: clinical audit of COPD exacerbations admitted to acute NHS units across the UK2008 Available from: http://bit.ly/2gLjlGVAccessed November 23, 2016

- MossMFranksMBriggsPKennedyDScholeyACompromised arterial oxygen saturation in elderly asthma sufferers results in selective cognitive impairmentJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol200527213915015903147

- ThakurNBlancPDJulianLJCOPD and cognitive impairment: the role of hypoxemia and oxygen therapyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010526326920856825

- Antonelli IncalziRMarraCGiordanoACognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a neuropsychological and spect studyJ Neurol2003250332533212638024

- LiJFeiGHThe unique alterations of hippocampus and cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Res20131414024359080

- DoddJWChungAWvan den BroekMDBarrickTRCharltonRAJonesPWBrain structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multimodal cranial magnetic resonance imaging studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186324024522652026

- DoddJWCharltonRAvan den BroekMDJonesPWCognitive dysfunction in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPDChest2013144111912723349026

- ChangSSChenSMcAvayGJTinettiMEEffect of coexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cognitive impairment on health outcomes in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc201260101839184623035917

- AmbrosinoNBrulettiGScalaVPortaRVitaccaMCognitive and perceived health status in patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surviving acute on chronic respiratory failure: a controlled studyIntensive Care Med200228217017711907660

- Ozyemisci-TaskiranOBozkurtSOKokturkNKaratasGKIs there any association between cognitive status and functional capacity during exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?Chron Respir Dis201512324725526071384

- FixAJDaughtonDKassIBellCWGoldenCJCognitive functioning and survival among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Neurosci1985271–213173926683

- Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial GroupContinuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trialAnn Intern Med19809333913986776858

- HjalmarsenAWaterlooKDahlAJordeRViitanenMEffect of long-term oxygen therapy on cognitive and neurological dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Neurol1999421273510394045

- KozoraEMakeBJCognitive improvement following rehabilitation in patients with COPDChest20001175 Suppl 1249S Abstract

- EmeryCFHonnVJFridDJLebowitzKRDiazPTAcute effects of exercise on cognition in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200116491624162711719300

- SchouLOstergaardBRasmussenLSTelemedicine-based treatment versus hospitalization in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and exacerbation: effect on cognitive function. A randomized clinical trialTelemed J E Health201420764064624820535

- BozekAKrajewskaJJarzabJThe improvement of cognitive functions in patients with bronchial asthma after therapyJ Asthma201047101148115221039205

- BlockAJCastleJRKeittASChronic oxygen therapy. Treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at sea levelChest19746532792884813834

- HeatonRKGrantIMcSweenyAJAdamsKMPettyTLPsychologic effects of continuous and nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med198314310194119476625781

- Dal NegroRWBonadimanLBricoloFPTognellaSTurcoPCognitive dysfunction in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with or without long-term oxygen therapy (ltot)Multidiscip Respir Med20151011725932326

- PrettoJJMcDonaldCFAcute oxygen therapy does not improve cognitive and driving performance in hypoxaemic COPDRespirology20081371039104418764913

- BoltonCEBevan-SmithEFBlakeyJDBritish thoracic society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adultsThorax201368Suppl 2ii1ii3023880483

- EmeryCFScheinRLHauckERMacIntyreNRPsychological and cognitive outcomes of a randomized trial of exercise among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth Psychol19981732322409619472

- EtnierJLBerryMFluid intelligence in an older COPD sample after short- or long-term exerciseMed Sci Sports Exerc200133101620162811581543

- EmeryCFShermerRLHauckERHsiaoETMacIntyreNRCognitive and psychological outcomes of exercise in a 1-year follow-up study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth Psychol200322659860414640857

- GregersenTLGreenAFrausingERingbaekTBrondumESuppli UlrikCDo telemedical interventions improve quality of life in patients with COPD? A systematic reviewInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20161180982227143872

- DangVMedinaBDasDFormoterol, a long-acting beta2 adrenergic agonist, improves cognitive function and promotes dendritic complexity in a mouse model of down syndromeBiol Psychiatry201475317918823827853

- VanmierloTCreemersPAkkermanSThe pde4 inhibitor roflumilast improves memory in rodents at non-emetic dosesBehav Brain Res2016303263326794595

- RayMSanoMWisniveskyJPWolfMSFedermanADAsthma control and cognitive function in a cohort of elderly adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc201563468469125854286

- VestboJHurdSSAgustiAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- MelaniASBonaviaMCilentiVInhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease controlRespir Med2011105693093821367593

- TaffetGEDonohueJFAltmanPRConsiderations for managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderlyClin Interv Aging20149233024376347

- QuinetPYoungCAHeritierFThe use of dry powder inhaler devices by elderly patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Phys Rehabil Med2010532697620018583

- ZarowitzBJO’SheaTChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, characteristics, and pharmacologic treatment in nursing home residents with cognitive impairmentJ Manag Care Pharm201218859860623127147

- DhandRDolovichMChippsBMyersTRRestrepoRFarrarJRThe role of nebulized therapy in the management of COPD: evidence and recommendationsCOPD201291587222292598

- BarronsRPegramABorriesAInhaler device selection: special considerations in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Health Syst Pharm201168131221123221690428

- DekhuijzenPNBjermerLLavoriniFNinaneVMolimardMHaughneyJGuidance on handheld inhalers in asthma and COPD guidelinesRespir Med2014108569470024636812

- YohannesAMManagement of anxiety and depression in patients with COPDExpert Rev Respir Med20082333734720477198

- MansonJESkerrettPJGreenlandPVanItallieTBThe escalating pandemics of obesity and sedentary lifestyle. A call to action for cliniciansArch Intern Med2004164324925814769621

- YohannesAMWillgossTGBaldwinRCConnollyMJDepression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principlesInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201025121209122120033905

- SireyJABruceMLAlexopoulosGSPerlickDAFriedmanSJMeyersBSStigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherencePsychiatr Serv200152121615162011726752

- YohannesAMConnollyMJBaldwinRCA feasibility study of antidepressant drug therapy in depressed elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200116545145411376459

- MemelDSKirwanJRSharpDJHehirMGeneral practitioners miss disability and anxiety as well as depression in their patients with osteoarthritisBr J Gen Pract20005045764564811042917

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPComorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186215516122561964

- SethiJMRochesterCLSmoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseClin Chest Med20002116786viii10763090

- WongSTMancaDBarberDThe diagnosis of depression and its treatment in Canadian primary care practices: an epidemiological studyCMAJ Open201424E337E342

- LuYNyuntMSZGweeXLife event stress and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): associations with mental well-being and quality of life in a population-based studyBMJ open201226e001674

- TeixeiraPJPortoLKristensenCHSantosAHMenna-BarretoSSDo Prado-LimaPAPost-traumatic stress symptoms and exacerbations in COPD patientsCOPD2015121909524983958

- WieseBSGeriatric depression: the use of antidepressants in the elderlyBCMJ2011537341347

- MaurerJRebbapragadaVBorsonSAnxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needsChest20081344 Suppl43S56S18842932

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand19836763613706880820

- BeckATEpsteinNBrownGSteerRAAn inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric propertiesJ Consult Clin Psychol19885668938973204199

- BeckATSteerRACarbinMGPsychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluationClin Psychol Rev19888177100

- FirstMBSpitzerRLGibbonMWilliamsJBStructured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0)New YorkBiometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute1995722

- Di NardoPMorasKBarlowDHRapeeRMBrownTAReliability of DSM-III-R anxiety disorder categories. Using the anxiety disorders interview schedule-revised (ADIS-R)Arch Gen Psychiatry19935042512568466385

- SpitzerRLWilliamsJBKroenkeKUtility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The Prime-MD 1000 studyJAMA199427222174917567966923

- FavreauHBaconSLLabrecqueMLavoieKLProspective impact of panic disorder and panic-anxiety on asthma control, health service use, and quality of life in adult patients with asthma over a 4-year follow-upPsychosom Med201476214715524470131

- LavoieKLJosephMFavreauHPrevalence of psychiatric disorders among patients investigated for occupational asthma: an overlooked differential diagnosis?Am J Respir Crit Care Med2013187992693223491404

- LavoieKLBoudreauMPlourdeACampbellTSBaconSLAssociation between generalized anxiety disorder and asthma morbidityPsychosom Med201173650451321715294

- NgTPNitiMTanWCCaoZOngKCEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med20071671606717210879

- PapaioannouAIBartziokasKTsikrikaSThe impact of depressive symptoms on recovery and outcome of hospitalised COPD exacerbationsEur Respir J201341481582322878874

- LaurinCMoullecGBaconSLLavoieKLThe impact of psychological distress on exacerbation rates in COPDTher Adv Respir Dis20115131821059699

- LaurinCMoullecGBaconSLLavoieKLImpact of anxiety and depression on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation riskAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012185991892322246177

- CuijpersPVogelzangsNTwiskJKleiboerALiJPenninxBWComprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnessesAm J Psychiatry2014171445346224434956

- DalesRESpitzerWOSchechterMTSuissaSThe influence of psychological status on respiratory symptom reportingAm Rev Respir Dis19891396145914632729753

- LiuLYCoeCLSwensonCAKellyEAKitaHBusseWWSchool examinations enhance airway inflammation to antigen challengeAm J Respir Crit Care Med200216581062106711956045

- EslerMThe sympathetic system and hypertensionAm J Hypertens2000136 Pt 299S105S10921528

- CohenSTyrrellDASmithAPNegative life events, perceived stress, negative affect, and susceptibility to the common coldJ Pers Soc Psychol19936411311408421249

- CohenSTyrrellDASmithAPPsychological stress and susceptibility to the common coldN Engl J Med199132596066121713648

- O’LearyASelf-efficacy and health: behavioral and stress-physiological mediationCogn Ther Res1992162229245

- PadgettDAGlaserRHow stress influences the immune responseTrends Immunol200324844444812909458

- NICEDepression in adults: recognition and managementClinical guideline10282009 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90/resources/depression-in-adults-recognition-and-management-975742636741Accessed June 6, 2016

- HynninenMJBjerkeNPallesenSBakkePSNordhusIHA randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in COPDRespir Med2010104798699420346640

- Farver-VestergaardIJacobsenDZachariaeREfficacy of psychosocial interventions on psychological and physical health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisPsychother Psychosom2015841375025547641

- SmithSMSonegoSKetchesonLLarsonJLA review of the effectiveness of psychological interventions used for anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBMJ Open Respir Res201411e000042

- YohannesAMAlexopoulosGSPharmacological treatment of depression in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact on the course of the disease and health outcomesDrugs Aging201431748349224902934

- CoventryPAHindDComprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation for anxiety and depression in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisJ Psychosom Res200763555156517980230

- AlexopoulosGSSireyJARauePJKanellopoulosDClarkTENovitchRSOutcomes of depressed patients undergoing inpatient pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200614546647516670251

- von LeupoldtATaubeKLehmannKFritzscheAMagnussenHThe impact of anxiety and depression on outcomes of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPDChest2011140373073621454397