Abstract

Introduction

An incremental approach using open-triple therapy may improve outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, there is little sufficient, real-world evidence available identifying time to open-triple initiation.

Methods

This retrospective study of patients with COPD, newly initiated on long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) monotherapy or inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β2-agonist (ICS/LABA) combination therapy, assessed baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and exacerbations during 12 months prior to first LAMA or ICS/LABA use. Time to initiation of open-triple therapy was assessed for 12 months post-index date. Post hoc analyses were performed to assess the subsets of patients with pulmonary-function test (PFT) information and patients with and without comorbid asthma.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics were similar between cohorts in the pre-specified and post hoc analyses. In total, 283 (19.3%) and 160 (10.9%) patients had moderate and severe exacerbations at baseline, respectively, in the LAMA cohort, compared with 482 (21.3%) and 289 (12.8%) patients in the ICS/LABA cohort. Significantly more patients initiated open-triple therapy in the LAMA cohort compared with the ICS/LABA cohort (226 [15.4%] versus 174 [7.7%]; P<0.001); results were similar in the post hoc analyses. Mean (standard deviation) time to open-triple therapy was 79.8 (89.0) days in the LAMA cohort and 122.9 (105.4) days in the ICS/LABA cohort (P<0.001). This trend was also observed in the post hoc analyses, though the difference between cohorts was nonsignificant in the subset of patients with PFT information.

Discussion

In this population, patients with COPD are more likely to initiate open-triple therapy following LAMA therapy, compared with ICS/LABA therapy. Further research is required to identify factors associated with the need for treatment augmentation among patients with COPD.

Introduction

Treatment options for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) such as inhaled bronchodilators (eg, long-acting muscarinic antagonists [LAMAs] and long-acting β2-agonists [LABAs]) and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are central to the pharmacological management of COPD.Citation1 LAMAs have been shown to improve lung function, relieve symptoms, increase exercise capacity, improve quality of life (QoL), and reduce COPD exacerbations to a greater extent than short-acting bronchodilators or placebo.Citation1–Citation4 Combination therapies containing ICS/LABAs are a recommended treatment option for patients with severe COPD or those at a high risk of exacerbations, and have been shown to improve both lung function and QoL, as well as reducing COPD exacerbations, compared with monotherapy components or placebo.Citation1,Citation5,Citation6

According to current COPD treatment guidelines, an incremental approach to pharmacological treatment of COPD is recommended, involving the use of treatment combinations with different or complementary mechanisms of action.Citation1,Citation7 Evidence suggests that open-triple therapy that incorporates a LAMA with ICS/LABA combination products, administered via separate delivery devices, may be beneficial in improving lung function and QoL in patients with COPD.Citation8–Citation11 Triple therapy is becoming increasingly important in clinical practice, with one analysis showing that ~20% of patients with COPD in the United States were using triple therapy over a 12-month period ending in 2012.Citation12

However, there has been minimal research on clinical characteristics or previous treatment patterns of patients initiating triple therapy. In addition, there is limited “real-world” information available regarding time to initiation of open-triple therapy, particularly in patients who have pulmonary-function testing (PFT) information available. To better understand patient groups that may benefit from this treatment option, it is important to assess the treatment patterns and clinical characteristics prior to initiation of open-triple therapy in real-world practice.

This retrospective study of patients with COPD, newly initiated on LAMA monotherapy or ICS/LABA combination therapy, assessed the clinical characteristics and time to initiation of open-triple therapy. Post hoc analyses of these data in subsets of patients with PFT information and patients with and without comorbid asthma were also performed.

Material and methods

Study design

This observational study (GSK study number: HO-13-13008) retrospectively assessed the time to initiation of open-triple therapy in patients with COPD who were initiated on long-acting inhaled therapy. Sources of patient data included health insurance claims and electronic medical records (EMR) from the Reliant Medical Group (RMG; Worcester, MA, USA), the Lovelace Health Plan (LHP), and Presbyterian Health Plan (PHP) (both Albuquerque, NM, USA). The analysis included RMG and PHP claims and records between January 2008 and September 2013, and records from LHP between January 2008 and December 2012.

The index date was defined as the date of first use of LAMA or ICS/LABA. The earliest index date was January 2009. Subjects were observed for a 12-month baseline period prior to the index date, and observed for up to 12 months after the index date. For all assessments, patients initiated on LAMA monotherapy were compared with patients initiated on ICS/LABA combination therapy.

The study was approved by Ethical and Independent Review Services (MO, USA), the RMG Institutional Review Board (MA, USA), and the Presbyterian Health Services Institutional Review Board (NM, USA), and was performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Good Clinical Practice guidelines, all applicable patient privacy requirements and the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013.Citation13,Citation14 Waivers of informed consent were granted by the institutional review boards that approved the study.

Patients

Eligible patients were males and females ≥40 years of age with at least one hospitalization or emergency room visit, or ≥2 outpatient visits (either with a primary or secondary diagnosis of COPD [International Classification of Disease-9th edition [ICD-9]-Clinical Modification codes: 491, 492, and 496]) during the 12-month baseline period; at least one prescription of long-acting inhaled therapy (ie, LAMA or ICS/LABA); and continuous enrollment for ≥12 months prior to the index date.

End points and assessments

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics evaluated during the 12 months prior to the index date (defined as the first use of LAMA or ICS/LABA) included smoking status, severity of COPD obstruction assessed by PFT, Charlson comorbidities based on ICD-9 codes,Citation15 specific respiratory-related comorbidities, and baseline medications. Exacerbation history at baseline was also assessed. Time to (and rate of) initiation of open-triple therapy (defined as a LAMA administered concomitantly with ICS/LABA therapy for ≥30 days of treatment) was evaluated for 12 months after the index date.

Among patients with PFT information, a forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio of <0.7 was required for a diagnosis of COPD to be confirmed, and severity (based on Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] stage) was determined by percentage of predicted FEV1.Citation1 Patients with an FEV1/FVC ratio of ≥0.7 and a percentage of predicted FEV1 <80% were classified as “restricted” and patients with an FEV1/FVC ratio of ≥0.7 and a percentage of predicted FEV1 ≥80% were classified as “unconfirmed COPD.”Citation1 Utilization files of all study patients were scanned for evidence that the patient underwent PFT at any time during the study period (current procedure terminology [CPT®, American Medical Association, Chicago IL, USA] codes: 94010–94620); the patient’s medical record was then abstracted. If more than one spirometry assessment was performed, the one closest to the time of long-acting inhaler therapy initiation was used to characterize the patient. Additional post hoc analyses were performed to evaluate the baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, exacerbation history, and time to (and rate of) initiation of open-triple therapy in patients who had PFT information available and patients with and without comorbid asthma.

Statistical analyses

Baseline assessments were summarized for between-cohort comparisons. The descriptive comparisons of the LAMA and ICS/LABA cohorts were prespecified; the post hoc analyses of patients with available spirometry data, and patients with and without comorbid asthma, used the same statistical methods as in the main analyses. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 or STATA version 10.0.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the observation period, the time to open-triple therapy, and the rates of treatment initiation at different time points following the index date. These data were compared between the cohorts initiated on LAMA or ICS/LABA. Categorical variables were assessed using Pearson Chi-square tests. Continuous variables were assessed using Student’s t-tests.

Time to and rate of initiation of open-triple therapy (including the additional post hoc analyses of patients with PFT information and patients with and without comorbid asthma) were compared between cohorts using Kaplan–Meier analysis, and statistical significance assessed using log-rank tests.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

In total, 1,463 and 2,259 patients were identified as newly initiated on LAMA monotherapy or ICS/LABA combination therapy, respectively (). In total, 208 (72.7% of 286) and 555 (74.5% of 745) RMG patients in the LAMA and ICS/LABA cohorts had EMR and claims information available, respectively. A total of 268 (26% of 1,031) RMG patients (in both cohorts) only had EMR information available. Overall, baseline demographics were similar across cohorts; the mean age waŝ71 years and 53%–55% of patients were female. Information on smoking status was unavailable for the majority of patients in each cohort. However, in patients where data were available, the proportion of current-, former-, or nonsmokers was similar between cohorts. PFT information was available for 371 (25%) patients in the LAMA cohort and 679 (30%) patients in the ICS/LABA cohort, and 269 (18%) and 447 (20%) patients had confirmed COPD (). Additionally, there were 324 (22.1%) patients with asthma in the LAMA cohort and 775 (34.3%) in the ICS/LABA cohort, leaving 1,139 (77.9%) patients without asthma in the LAMA cohort and 1,484 (65.7%) in the ICS/LABA cohort. A similar proportion of patients experienced moderate-to-very severe COPD in each cohort ().

Table 1 Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

During the 12-month baseline period, the LAMA cohort had a significantly lower proportion of patients with ≥2 respiratory-related comorbidities compared with the ICS/LABA group (). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) follow-up period was 321 (93) days in the LAMA cohort and 320 (92) days in the ICS/LABA cohort.

Patients in the LAMA cohort reported significantly less rescue or baseline medication use (ICS, short-acting β-agonists/short-acting muscarinic antagonists [SABA/SAMA] and SABA) compared with the ICS/LABA cohort. Supplemental oxygen use was reported for a similar proportion of patients in the LAMA and ICS/LABA cohorts ().

Overall, demographics and clinical characteristics were generally similar between treatment cohorts in the subsets of patients who had PFT information available and with or without comorbid asthma (). However, among those with PFT information available, patients initiating on LAMA compared with ICS/LABA were significantly older and a significantly lower percentage were female.

Table 2 Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics in subsets of patients

Baseline exacerbations

During the 12-month baseline period, 283 (19.3%) and 160 (10.9%) patients in the LAMA cohort had a history of moderate and severe exacerbations, compared with 482 (21.3%) and 289 (12.8%) patients in the ICS/LABA cohort, respectively ().

Table 3 Summary of baseline exacerbations

Similar results were observed in patients who had PFT information available and patients without comorbid asthma (ie, a slightly higher proportion of patients had moderate or severe exacerbations at baseline in the ICS/LABA versus the LAMA cohort). No significant differences were identified in the proportions of patients with moderate or severe exacerbations at baseline between the ICS/LABA and LAMA cohorts in patients with PFT information or patients with comorbid asthma. However, in patients without asthma, the proportion of patients with severe exacerbations at baseline was significantly higher in the ICS/LABA cohort than in the LAMA cohort ().

Table 4 Summary of baseline exacerbations in subsets of patients

Time to initiation of open-triple therapy

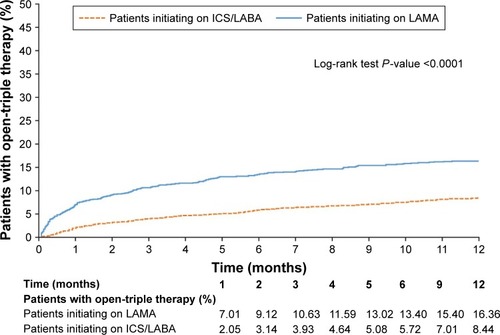

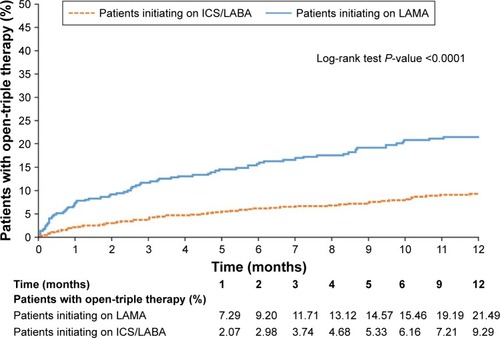

A significantly higher proportion of patients in the LAMA cohort initiated open-triple therapy compared with the ICS/LABA cohort (). Results were similar (also significant) in patients who had PFT information available and patients with and without asthma; in patients who had PFT information available and patients with asthma, considerably greater proportions of patients in the LAMA cohort initiated open-triple therapy than in the overall population ().

Table 5 Time to initiation of open-triple therapy at 12 months (post-index date)

The mean (SD) time to initiation of open-triple therapy was 79.8 (89.0) days in the LAMA cohort and 122.9 (105.4) days in the ICS/LABA cohort (P<0.001). Patients with PFT information demonstrated a higher mean time to initiation of open-triple therapy than patients in the prespecified analysis, and there was no significant difference between LAMA and ICS/LABA cohorts (P=0.166). Patients with asthma demonstrated a slightly higher mean time to initiation of open-triple therapy than patients in the prespecified analysis; as in that analysis, the LAMA cohort had significantly less time to initiation than the ICS/LABA cohort. Patients without asthma had similar times to initiation to patients in the prespecified analysis; again, patients in the LAMA cohort had significantly less time to initiation than the ICS/LABA cohort ().

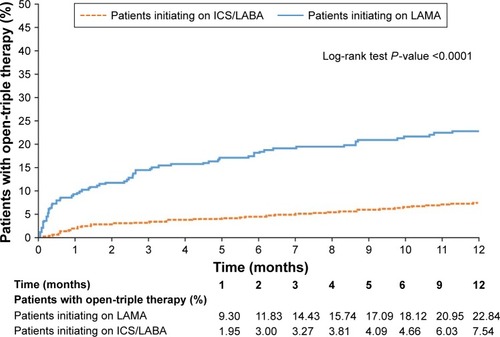

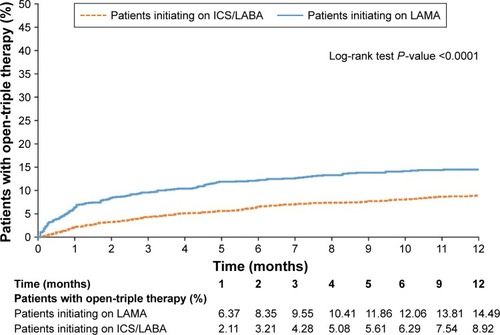

The Kaplan–Meier analyses showed that patients in the LAMA cohort had a significantly higher rate of open-triple therapy initiation compared with patients in the ICS/LABA cohort at 12 months (). Among patients with PFT information available, a significantly higher rate of initiation of open-triple therapy was also observed in the LAMA cohort compared with the ICS/LABA cohort at 12 months (). Additionally, in patients with asthma, the LAMA cohort had a significantly higher rate of open-triple therapy initiation compared with those in the ICS/LABA cohort at 12 months; the difference between cohorts was greater than in the overall population (). In patients without asthma, the LAMA cohort again had a significantly higher rate of open-triple therapy initiation compared with the ICS/LABA cohort at 12 months, but the difference between cohorts was less than in the overall population ().

Figure 1 Kaplan–Meier curve to show rates of open-triple therapy initiation at 12 months (post-index date).

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier curve to show rates of open-triple therapy initiation at 12 months (post-index date) in patients with pulmonary-function testing information.

Abbreviations: ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist.

Discussion

This observational study retrospectively assessed the time to initiation of open-triple therapy in patients with COPD who were initiated on long-acting inhaled bronchodilator or long-acting bronchodilator plus ICS combination therapy. Additional post hoc analyses for initiation of open-triple therapy in patients who had PFT information available were also performed. Sensitivity analyses were also performed for initiation of open-triple therapy in patients with and without a potential asthma comorbidity.

Overall, the crude percentage of patients with COPD initiated on LAMA monotherapy who augmented to open-triple therapy was twice that of patients with COPD initiated on ICS/LABA therapy. This difference was apparent in the first few months after the index date and was significant in the prespecified analyses; similar findings were observed in the post hoc analyses of patients with available PFT information and patients with and without asthma. Moreover, rate and time-to-event analyses showed that open-triple therapy initiation was also significantly different in the LAMA cohort compared with the ICS/LABA cohort. Again, similar results were observed in the subsets of patients with available PFT information and patients with and without asthma. Other observational studies have indicated that up to 25% of patients with COPD receiving maintenance mono- or combination therapies (either LAMA or ICS/LABA, respectively) may switch to, or concomitantly receive, other long-acting treatments.Citation16–Citation18 This may be due to an actual or perceived lack of efficacy.

In line with these findings, the data presented here provide real-world evidence that patients with COPD are more likely to initiate open-triple therapy following initiation with LAMA monotherapy, compared with ICS/LABA therapy. This advance to triple therapy was less likely among patients receiving ICS/LABA even though they had more indications of disease instability during the pre-index period, such as a higher incidence of moderate and severe COPD exacerbations and increased rate of “rescue or baseline” inhaler use. In addition, there were considerably more patients on ICS/LABA therapy than LAMA therapy at baseline. This preference in starting treatment might suggest a lower threshold for adding an ICS/LABA to LAMA therapy, compared with adding a LAMA to ICS/LABA therapy. As the GOLD guidelines state that prescriptions of bronchodilator therapy for patients with COPD should be “on an as-needed or regular basis to prevent or reduce symptoms,” these findings may indicate that unspecified factors (other than moderate or severe exacerbation events) are a driving factor for clinical decisions to advance to triple therapy more quickly on LAMA versus ICS/LABA. Indeed, other clinical factors such as adverse events (eg, the risk of acute urinary retention potentially associated with use of LAMAs in men with benign prostatic hyperplasiaCitation19), or nonclinical factors such as patient satisfaction with treatment, may not be easily captured in utilization databases but could also affect clinical treatment decisions. Findings from a previous study suggest that clinical characteristics and events presenting long before the initiation of monotherapy can be predictive of subsequent treatment adherence or changes to treatment.Citation20 It is also possible that other agents could be added to either LAMA or ICS/LABA therapy as an alternative to progression to ICS/LABA/LAMA triple therapy. For example, the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor roflumilast has been shown to improve patient outcomes when added to both LAMA monotherapyCitation21 and ICS/LABA combination therapy.Citation22 While roflumilast use in this study was very low (<1%), and therefore would not have substantially affected the overall findings, it would be interesting to assess the rates of addition of alternative treatments in future studies. The increasing awareness of the potential benefits of LAMA/LABA combination therapy versus LAMA or LABA monotherapyCitation23,Citation24 has introduced an alternative route to triple therapy with the subsequent addition of ICS to a LAMA/LABA combination. Limited data are currently available comparing the efficacy of triple therapy with LAMA/LABA therapy;Citation1,Citation9,Citation25 however, it would be interesting to compare the rate of escalation to triple therapy from LAMA/LABA combinations with those from LAMA or ICS/LABA therapies. As such, additional research examining the factors influencing physician treatment decisions and patient treatment experience in COPD is warranted.

A limitation of this study is that claims databases may contain inaccuracies or omissions, particularly with respect to procedures or diagnoses. It should also be noted that a proportion of the RMG patient data were only available through EMR; therefore, information on health care services obtained outside of the group may be missing. In addition, not all prescriptions reported may have been used by the patients. As the results were collected from patients from the USA only, further evidence is required to demonstrate that these findings apply to wider patient populations. Finally, as the incidence of initiation of open-triple therapy was <25% in either cohort, the calculation of time-to-event is less robust than would be the case if 50% of the population augmented to open-triple therapy; consequently, the differences observed between cohorts should be viewed with caution.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of this analysis show that patients in the study population with COPD receiving LAMA monotherapy are more likely to initiate open-triple therapy than those receiving ICS/LABA. These findings were consistent between patients who had a primary or secondary diagnosis of COPD, those with PFT information, and those with and without comorbid asthma. Further research is required to identify clinical or nonclinical factors associated with treatment augmentation in patients with COPD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Judith Gilmore of the Reliant Medical Group, Worcester, MA (now retired), and Ann Von Worley of LCF Research, Albuquerque, NM, USA who assisted with the study administration and collation of study data.

This study was funded by GSK (study number: HO-13-13008). Editorial support in the form of writing assistance, including development of the initial draft based on instruction from the authors, assembling tables and figures, collating authors’ comments, grammatical editing, and referencing was provided by David Griffiths, PhD, when he was an employee of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK. Subsequent editorial support in the form of writing assistance, including minor revisions and grammatical editing, was provided by Elizabeth Jameson, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Disclosures

DM and MHR were employed by Lovelace Clinic Foundation at the time this study was conducted. Besides the funding Lovelace Clinic Foundation received to conduct this study, both have received grant funding from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., GSK, EndoPharmaceuticals, and Pfizer Inc. to conduct other COPD-related research. DM has also received grant funding from Sunovian Pharmaceuticals for other research unrelated to this project. SRS and DS are employees of Reliant Medical Group, who received research funding from GSK to conduct the study. DP, FL, MSD, and PL are employees of Groupe d’analyse/Analysis Group, a consulting company that received research funds from GSK to conduct the study. Groupe d’analyse/Analysis Group has also received research funds from GSK, Novartis, Janssen Pharmaceutical Affairs, LLC, Bayer, and other pharmaceutical companies to conduct other respiratory disease studies. JP was an employee of GSK at the time of study conduct and owned stocks and shares in GSK. He is currently employed by, and owns stocks and shares in, Amgen. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GOLDGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [updated 2017] Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed January 25, 2017

- BarrRGBourbeauJCamargoCARamFSInhaled tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20052CD00287615846642

- CheyneLIrvin-SellersMJWhiteJTiotropium versus ipratropium bromide for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20139CD009552

- KestenSCasaburiRKukafkaDCooperCBImprovement in self-reported exercise participation with the combination of tiotropium and rehabilitative exercise training in COPD patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083112713618488436

- CalverleyPMAAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- CalverleyPMBoonsawatWCsekeZZhongNPetersonSOlssonHMaintenance therapy with budesonide and formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200322691291914680078

- CelliBRMacNeeWATS/ERS Task ForceStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J200423693294615219010

- WelteTMiravitllesMHernandezPEfficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol added to tiotropium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009180874175019644045

- AaronSDVandemheenKLFergussonDTiotropium in combination with placebo, salmeterol, or fluticasone-salmeterol for treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2007146854555517310045

- SilerTMKerwinESousaARDonaldAAliRChurchAEfficacy and safety of umeclidinium added to fluticasone furoate/vilanterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Results of two randomized studiesRespir Med201510991155116326117292

- SilerTMKerwinESingletaryKBrooksJChurchAEfficacy and safety of umeclidinium added to fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in patients with COPD: results of two randomized, double-blind studiesCOPD201613111026451734

- TashkinDPFergusonGTCombination bronchodilator therapy in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Res2013144923651244

- International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human UseICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice E6(R1)1996 Available from: https://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdfAccessed March 16, 2017

- World Medical Association [webpage on the Internet]WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects2013 Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.htmlAccessed March 16, 2017

- QuanHSundararajanVHalfonPCoding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative dataMed Care200543111130113916224307

- BlaisLForgetARamachandranSRelative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in a 1-year, population-based, matched cohort study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): effect on COPD-related exacerbations, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, medication utilization, and treatment adherenceClin Ther20103271320132820678680

- DalalAARobertsMHPetersenHVBlanchetteCMMapelDWComparative cost-effectiveness of a fluticasone-propionate/salmeterol combination versus anticholinergics as initial maintenance therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201161322

- RobertsMMapelDPetersenHBlanchetteCRamachandranSComparative effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol and fluticasone/salmeterol for COPD managementJ Med Econ201114676977621942463

- LokeYKSinghSRisk of acute urinary retention associated with inhaled anticholinergics in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease: systematic reviewTher Adv Drug Saf201341192625083248

- RobertsMHMapelDWBorregoMERaischDWGeorgopoulosLvan der GoesDSevere COPD exacerbation risk and long-acting bronchodilator treatments: comparison of three observational data analysis methodsDrugs Real World Outcomes20152216317527747765

- FabbriLMCalverleyPMIzquierdo-AlonsoJLRoflumilast in moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with longacting bronchodilators: two randomised clinical trialsLancet2009374969169570319716961

- MartinezFJCalverleyPMGoehringUMBroseMFabbriLMRabeKFEffect of roflumilast on exacerbations in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease uncontrolled by combination therapy (REACT): a multicentre randomised controlled trialLancet2015385997185786625684586

- CalzettaLRoglianiPMateraMGCazzolaMA systematic review with meta-analysis of dual Bronchodilation with LAMA/LABA for the treatment of stable COPDChest201614951181119626923629

- CohenJSMilesMCDonohueJFOharJADual therapy strategies for COPD: the scientific rationale for LAMA + LABAInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20161178579727143870

- MagnussenHDisseBRodriguez-RoisinRWISDOM InvestigatorsWithdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2014371141285129425196117