Abstract

Background

Self-management interventions (SMIs) are recommended for individuals with COPD to help monitor symptoms and optimize health-related quality of life (HRQOL). However, SMIs vary widely in content, delivery, and intensity, making it unclear which methods and techniques are associated with improved outcomes. This systematic review aimed to summarize the current evidence base surrounding the effectiveness of SMIs for improving HRQOL in people with COPD.

Methods

Systematic reviews that focused upon SMIs were eligible for inclusion. Intervention descriptions were coded for behavior change techniques (BCTs) that targeted self-management behaviors to address 1) symptoms, 2) physical activity, and 3) mental health. Meta-analyses and meta-regression were used to explore the association between health behaviors targeted by SMIs, the BCTs used, patient illness severity, and modes of delivery, with the impact on HRQOL and emergency department (ED) visits.

Results

Data related to SMI content were extracted from 26 randomized controlled trials identified from 11 systematic reviews. Patients receiving SMIs reported improved HRQOL (standardized mean difference =−0.16; 95% confidence interval [CI] =−0.25, −0.07; P=0.001) and made fewer ED visits (standardized mean difference =−0.13; 95% CI =−0.23, −0.03; P=0.02) compared to patients who received usual care. Patients receiving SMIs targeting mental health alongside symptom management had greater improvement of HRQOL (Q=4.37; P=0.04) and fewer ED visits (Q=5.95; P=0.02) than patients receiving SMIs focused on symptom management alone. Within-group analyses showed that HRQOL was significantly improved in 1) studies with COPD patients with severe symptoms, 2) single-practitioner based SMIs but not SMIs delivered by a multidisciplinary team, 3) SMIs with multiple sessions but not single session SMIs, and 4) both individual- and group-based SMIs.

Conclusion

SMIs can be effective at improving HRQOL and reducing ED visits, with those targeting mental health being significantly more effective than those targeting symptom management alone.

Introduction

COPD is characterized by airflow limitation and is associated with inflammatory changes that lead to dyspnea, sputum purulence, and persistent coughing. The disease trajectory is one of progressive decline, punctuated by frequent acute exacerbations in symptoms. Patients with COPD have an average of three acute exacerbations per year, and these are the second biggest cause of unplanned hospital admissions in the UK.Citation1–Citation3 As COPD is irreversible, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in patients with COPD tends to be low, optimizing HRQOL and reducing hospital admissions have become key priorities in COPD management.Citation4,Citation5

Self-management planning is a recognized quality standard of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines in the UK,Citation2 and a joint statement by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory SocietyCitation6 emphasized its importance in quality of care. Self-management interventions (SMIs) encourage patients to monitor symptoms when stable and to take appropriate action when symptoms begin to worsen.Citation2 However, there is no consensus on the form and content of effective SMIs and the variation in content may explain previous heterogeneity in effectiveness.Citation2,Citation7,Citation8 A recent Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report on the efficacy of self-management for COPD recommended that future research should 1) “try to identify which are the most effective components of interventions and identify patient-specific factors that may modify this”, and that 2) “behavior change theories and strategies that underpin COPD SMIs need to be better characterized and described”.Citation8 To enable better comparison and replication of intervention components, taxonomies have been developed to classify potential active ingredients of interventions according to preestablished descriptions of behavior change techniques (BCTs).Citation9 BCTs are defined as “an observable, replicable, and irreducible component of an intervention designed to alter or redirect causal processes that regulate behavior”.Citation9 While recent reviews have conducted content analysis to help identify effective components of SMIs for patients with COPD through individual patient data analysis,Citation10,Citation11 the coding of intervention content was not performed with established taxonomies and clear understanding between the BCT and the targeted behavior was absent (eg, symptom management, physical activity, mental health management, etc).

This systematic review aims to summarize the current evidence base on the effectiveness of SMIs for improving HRQOL in people with COPD. Conclusions across reviews have been synthesized and evaluated within the context of how self-management was defined. Meta-analyses were performed that explore the relationship between health behaviors the SMIs target, the BCT they use to target behaviors, and subsequent improvement in HRQOL and health care utilization. In addition, we explore the extent to which trial and intervention features influence SMI effects.

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

The current review, registered with PROSPERO (CRD42 016043311), is available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016043311. To focus the search upon high-quality systematic reviews, we searched two databases of systematic reviews: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Wiley) issue 7 of 12 2016, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (Wiley) issue 2 of 4 2015 (latest available). In addition, we searched Ovid MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE® 2015 with a systematic review filter available from CADTH.Citation12 All search results were screened for title and abstract by one reviewer (JN), and 20% of the results were screened by a second reviewer (KH-M) to ensure comparability. Two reviewers screened the search results at the full paper review stage. The search strategy (ran up to October 1, 2016) combined database-specific thesaurus headings and keywords describing COPD and self-management:

exp Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive

emphysema$.tw.

(chronic$ adj3 bronchiti$).tw.

(obstruct$ adj3 (pulmonary or lung$ or bronch$ or respirat$)).tw.

(COPD or COAD or COBD or AECB).tw.

or/1–5

exp Self Care/

(self-manag$ or self manag$ or self-car$ or self car$ or self-administ$ or self administ$).tw.

(patient$ adj3 (focus$ or participat$ or centr$ or center$ or empower$ or support$ or collaborat$ or co-operat$ or cooperat$)).tw.

or/7–9

6 and 10.

The review approach provides an overview of existing systematic reviews and is particularly helpful where multiple systematic reviews have been conducted. A review also provides an opportunity to compare the summaries and findings of previous reviews. In the present review, both a meta-analysis and narrative synthesis were conducted. The narrative synthesis compared the overview of findings as presented by the original authors, whereas meta-analyses were conducted on data from individual studies presented within the reviews. These quantitative analyses are helpful to determine the effectiveness of SM interventions and the factors that influence their effectiveness.

To be eligible for the narrative synthesis, reviews had to focus upon interventions that targeted self-management. We sought to explore variations in definitions of self-management used by previous authors, and thus reviews were eligible if they specified they focused on SMIs, irrespective of the definition they applied. Reviews that focused on SMIs in addition to other types of interventions (eg, pulmonary rehabilitation, supervised exercise programs) were only eligible if the SMIs could be clearly separated from the other interventions. Reviews of interventions delivered in primary, secondary, tertiary, outpatient, or community care were eligible.

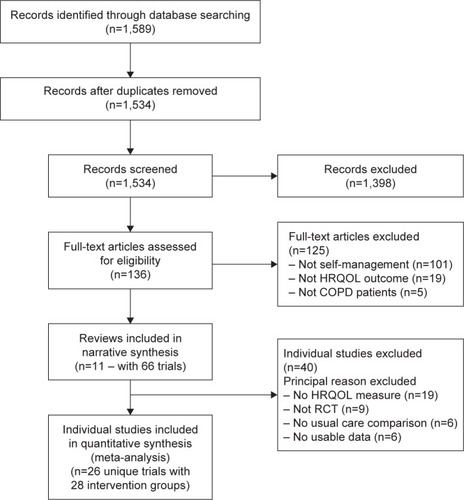

To be eligible for the quantitative analyses, randomized controlled trials delivered in primary, secondary, tertiary, outpatient, or community care were eligible if they 1) targeted patients with COPD (diagnosed by either a clinician/health care practitioner and/or agreed spirometry criteria, ie, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) <70%),Citation13 2) compared the SMI to a comparison group that received usual care during the study period, and 3) had a measure of HRQOL as an outcome measure. Studies were excluded if they involved mixed disease populations where COPD patients could not be separated for analysis. provides a PRISMA diagram of reviews, and the trials within reviews, eligible for inclusion.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was HRQOL measured by the Saint George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ). The SGRQ is a disease-specific instrument designed to measure impact on overall health, daily life, and perceived well-being in patients with obstructive airways disease.Citation14 The measure provides a total score and subdomain scores of symptoms (frequency and severity of symptoms), activities (activities that cause or are limited by breathlessness), and impacts (social functioning and psychological disturbances resulting from airways disease) and is the most frequently used disease-specific measure of HRQOL in this population group.Citation15 Where trials did not use the SGRQ, scores from alternative HRQOL measures were used; the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ), Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ), or Sickness Impact Profile (SIP).Citation16–Citation18 We combined scores across different questionnaires for meta-analyses, as total SGRQ, CRQ, CCQ, and SIP scores have been shown to correlate well and as subdomain constructs share conceptual similarity.Citation19–Citation22 Studies using alternative HRQOL measures were not eligible.

Classification of intervention content and intervention delivery features

The Behavior Change Techniques Taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1) was used to code the content of intervention descriptions.Citation9 Intervention descriptions were separately coded for self-management behaviors that targeted 1) symptoms, 2) physical activity, and 3) mental health. For instance, the description “patients were instructed to set themselves a walking goal each day” would be coded as “goal setting (behavior)” only for “physical activity” and not “mental health self-management” or “symptoms self-management.” Consequently, it is important to use an outcome measure where changes in score reflect a change in these behaviors; and these three behaviors of symptoms, physical activity, and mental health directly map on to the three subdomains of the SGRQ (ie, Symptoms, Activities, and Impacts, respectively). Examples of symptom-specific behaviors may include teaching appropriate inhalation techniques or mucus-clearing techniques.Citation2 In contrast, physical activity behaviors may be structured exercise programs, techniques on how to incorporate light activity into daily routine, or energy conservation techniques.Citation2 Finally, mental health-focused behaviors may include trying to teach patients communication strategies to help communicate mental health concerns, distraction techniques, relaxation exercises, or stress counseling.Citation2

To identify whether any features of the delivery of the intervention itself influenced effectiveness, interventions were coded for intervention provider (multidisciplinary team or single practitioner), intervention format (individual or group-based), and intervention length (single session or multiple session).Citation23 The BCTs identified and intervention features of delivery were coded independently by one reviewer (JN) and checked independently by another (KH-M) (κ=0.89; 95% CI =0.82, 0.96). To determine the length of an intervention, the end point was defined as the final time participants received intervention content from the intervention provider. Intervention contacts solely for data collection or for following up on participants without new content were not classed as intervention sessions. To assess whether intervention effects depend on disease severity, studies were divided into those with patients with mean predicted FEV1 score <50% or ≥50% at baseline.Citation13

Data relating to the number of COPD-related emergency department (ED) visits and/or hospital admissions were extracted from eligible studies, where reported, and used to see whether fewer ED visits were reported in patients receiving SMIs compared to patients receiving usual care. Subsequently, SMIs were divided between those with and without BCTs targeting mental health and physical activity in order to examine whether they had a difference in the size of their effect in comparison to patients who received usual care.

Data extraction and analysis

The original studies were sought for further data extraction, to supplement the information reported in the reviews. Data reported at the follow-up time point most closely following the end point of the intervention period were used for meta-analyses. We decided to group patients across time points as patients with COPD have high mortality rates; of those patients who are admitted, 15% will die within 3 months,Citation24 25% will die within 1 year,Citation2 and 50% within 5 years.Citation25 While prespecifying a follow-up time point limits the bias of treatment reactivity, we may be excluding patients with shorter survival, who may not necessary survive to a later time point, who are likely to be those most in need of interventions that improve HRQOL. Sensitivity analyses were performed for studies collecting outcome data at less than 6 months and 6-month and 12-month follow-up to explore any potential heterogeneity in the overall analysis. Data from intention-to-treat analyses were used where reported. If two interventions were compared against a control group (eg, action plans vs education vs usual care), data from both intervention arms were included in the main comparison and the number of participants in the control group was halved for each comparison.Citation26

Postintervention outcomes reported as mean and SD were used for analysis. Mean change scores were used if postintervention scores were unavailable. When mean and SD values were unavailable, missing data were imputed using the median instead of the mean and by estimating the SD from the standard error, confidence intervals (CIs), or interquartile range.Citation26,Citation27

Standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs were calculated and pooled using a random effects model for all studies. Dichotomous and continuous outcomes were merged using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software (v2.2, Biostat; Englewood, NJ, USA) to produce SMDs for each study, which are equivalent to Cohen’s d. SMD values of at least 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 are indicative of small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.Citation28 Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Cochran Q test and I2 test statistics.Citation26

Random effects subgroup analyses with Q statistic tests were conducted using CMA software. Univariate moderator analyses were conducted to compare effect size between SMIs with moderate/severe COPD, single/multiple sessions, and single/multiple practitioners. Univariate moderator analyses were also used to compare SMIs with/without BCTs targeting mental health self-management and physical activity to examine whether they differed in effect for the number of ED visits in comparison to patients receiving usual care. Random effects univariate meta-regression was conducted using CMA software to examine whether the number of BCTs coded across SMIs was predictive of effectiveness.

Results

Narrative synthesis

Eleven reviews were eligible for inclusion,Citation7,Citation10,Citation11,Citation29–Citation36 covering 66 clinical trials (). The decision over whether to include three reviews warranted further discussion and the rationale for inclusion/exclusion is detailed in Supplementary material. Reviews varied widely in their definitions of self-management and the number of individual studies that met their inclusion criteria ( and ). Zwerink et alCitation7 reported a significant effect of SMIs on HRQOL but did state that “heterogeneity among interventions, study populations, follow-up time, and outcome measures makes it difficult to formulate clear recommendations regarding the most effective form and content of self-management in COPD”. Jonkman et alCitation10 showed SMIs to improve HRQOL in COPD patients at 6 and 12 months but did not identify any components of the SMIs that were associated with the intervention. The more recent reviews had strict inclusion criteria and were smaller in size as a result.Citation30,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36 Harrison et alCitation33 and Majothi et alCitation34 focused on hospitalized and recently discharged patients. Harrison et alCitation33 did not find any significant differences in total or domain scores for HRQOL. In contrast, Majothi et al et alCitation34 did find a significant effect on total SGRQ, but stressed that this finding should be treated with caution due to variable follow-up assessments. Walters et alCitation36 focused on more restrictive criteria for interventions that were action plans and found no significant effect on HRQOL. Bentsen et alCitation30 were less clear in their definition of an SMI, and this may explain the smaller number of studies. The authors reported that the majority of studies showed a benefit on HRQOL, but no meta-analysis was performed.

Table 1 Definitions of “self-management” used across reviews

Table 2 Overlap of individual studies across reviews

Quantitative synthesis

Twenty-six eligible, unique trials provide data on 28 intervention groups ( and ). In total, trials reported on 3,518 participants (1,827 intervention, 1,691 control) for this analysis. Mean age of participants was 65.6 (SD =1.6; range =45–89) years. The majority of participants were male (72%). Characteristics of included trials are reported in their respective reviews (). details which specific BCTs were used in each SMI. displays which intervention features and target behaviors were used in each SMI. SMIs showed a significant but small positive effect in improving HRQOL scores over usual care (SMD =−0.16; 95% CI =−0.25, −0.07; P=0.001). Statistical heterogeneity was moderate but significant (I2=36.6%; P=0.03), suggesting the need for further moderator/subgroup analyses (). When studies using measures other than the SGRQ (n=6) were excluded, SMIs continued to show a significant effect on improving HRQOL, which was of comparable effect size (SMD =−0.16; 95% CI =−0.26, −0.05; P=0.003). SMIs with 12-month follow-up (n=15) were significantly more effective than usual care (SMD =−0.16; 95% CI =−0.29, −0.03; P=0.02), but significant heterogeneity existed between studies (I2=53.4%; P=0.008). In trials with 6-month follow-up (n=10), there was no significant difference in effect between SMIs and control group on HRQOL (SMD =−0.11; 95% CI =−0.27, 0.04; P=0.14) and even heterogeneity between studies was not significant (I2=26.2%; P=0.20). In trials with a follow-up less than 6-month postintervention (n=7), SMIs were significantly more effective than usual care (SMD =−0.29; 95% CI =−0.48, −0.11; P=0.002) and there was no significant heterogeneity (I2=2.4%; P=0.41).

Table 3 BCTs used across studies eligible in meta-analysis

Table 4 Intervention features and number of BCTs targeting different behaviors across SMIs

Table 5 SMD, 95% CIs for the effect of self-management interventions compared with control conditions on measures of health-related quality of life, with measures of heterogeneity

Intervention delivery features

In comparison to patients receiving usual care, there were no significant differences in effect size in between-group comparisons of 1) single session vs multiple session SMIs, 2) SMIs delivered by a single practitioner vs multidisciplinary teams, 3) SMIs targeting patients with moderate vs severe symptoms, and 4) individual-based vs group-based SMIs (). However, within-group moderator analysis showed 1) SMIs to be significantly effective in COPD patients with severe symptoms, whereas no significant effect was observed in studies that recruited patients with moderate symptoms; 2) significant improvement with SMIs delivered by a single practitioner, while no effect with multidisciplinary interventions; 3) no effect with single-session SMIs, but significant improvement with SMIs with multiple sessions; and 4) significant improvement in HRQOL was observed in both individual and group-based SMIs ().

SMIs targeting mental health had a significantly greater effect size than SMIs not targeting mental health management (Q=4.37; k=28; P=0.04) (). Within-group analysis showed SMIs that did not target mental health had no significant effect on HRQOL. There was no difference in effect size between SMIs targeting and not targeting physical activity, with both groups of SMIs showing significant improvement in improving HRQOL in comparison to usual care.

Intervention content

All interventions were coded for at least one BCT that targeted symptom management. Of these 24 interventions, five targeted solely symptom management (20.8%), three targeted management of mental health concerns (12.5%), eleven targeted physical activity (45.8%), and five targeted all three behaviors (20.8%). The number of interventions reporting BCTs that target each of the three behaviors is presented in and . Across interventions, a mean of eight BCTs per intervention was coded (SD =3; range =3–13), with a mean of five BCTs (SD =2; range =2–10) for symptom management, one BCT (SD =1; range =0–4) for mental health management, and two BCTs (SD =3; range =0–10) for physical activity. For symptom management, the three most common BCTs reported were “instruction on how to perform a behavior” (n=23/24 trials; 95.8%), “information about health consequences” (n=21/24; 87.5%), and “action planning” (n=16/24; 66.7%). For physical activity, the three most common BCTs reported were “instruction on how to perform a behavior” (n=11/16 trials; 68.8%), “goal setting (behavior)” (n=8/16; 50%), and “demonstration of the behavior” (n=8/16 trials; 50%). For management of mental health concerns, the three most common BCTs reported were strategies to “reduce negative emotions” (n=4/8 trials; 50%), “provide social support (unspecified)” (n=3/8 trials; 37.5%), and “monitoring of emotional consequences” (n=3/8 trials; 37.5%). Sixty-six (70.9%) of the 93 BCTs in the BCTTv1 were not coded in any intervention. There was no significant association between the number of BCTs used and intervention effectiveness for improving HRQOL (β=−0.01; 95% CI =−0.04, 0.01; k=28; Q=1.75; P=0.19).

Health care use

Overall, patients who received SMIs had significantly fewer ED visits compared to those who received usual care (SMD =−0.13; 95% CI =−0.23, −0.03; n=15; P=0.02). There was no significant heterogeneity in the sample (I2=19.4%; P=0.24). The significant effect of SMIs on the number of ED visits in patients who received SMIs remained when examining only studies with a 12-month follow-up (SMD =−0.17, 95% CI =−0.27, −0.07; n=12; P=0.001) with no significant heterogeneity (I2=10.4%; P=0.34). Of the three intervention groups that did not have a 12-month follow-up, only one used a 3-month follow-up and the two were from the same study where a 6-month follow-up was used. Thus, meta-analyses were not performed for either 3-month or 6-month follow-up time points.

Within-group analyses revealed patients receiving SMIs targeting mental health made significantly fewer ED visits compared to patients receiving usual care (SMD =−0.22; 95% CI =−0.32, −0.11; k=5; P<0.001). No difference was observed in the number of ED visits between patients receiving SMIs not targeting mental health and patients receiving usual care (SMD =0.001; 95% CI =−0.14, 0.14; k=10 P=0.99). This led to a significant between-group difference in effect between SMIs targeting mental health compared to SMIs not targeting mental health (Q=5.95; P=0.02).

Patients receiving SMIs targeting physical activity made significantly fewer ED visits compared to those who received usual care (SMD =0.20; 95% CI =−0.31, −0.08; k=8; P=0.001). No difference was observed between patients receiving SMIs not targeting physical activity and usual care (SMD =−0.03; 95% CI =−0.18, 0.12; k=7; P=0.68). In comparison to usual care, there was no difference in effect between SMIs targeting and not targeting physical activity (Q=3.03; k=15; P=0.08).

Discussion

The meta-analysis showed SMIs were significantly more effective than usual care in improving HRQOL and reducing the number of ED visits in patients with COPD. In addition, moderator analyses provided specific detail of relevance for clinicians regarding the design, content, and implementation of intervention in practice. SMIs that specifically target mental health concerns alongside symptom management were significantly more effective in improving HRQOL and reducing ED visits than SMIs that focus on symptom management alone. Within-group analyses showed that HRQOL was significantly improved in 1) studies with COPD patients with severe level of symptoms but not in patients with a moderate level of symptoms, 2) single-practitioner based SMIs but not in SMIs delivered by a multidisciplinary team, 3) SMIs with multiple sessions but not in SMIs delivered in a single session, 4) both individual- and group-based interventions, and 5) SMIs that target physical activity. Our analysis also highlighted how different BCTs were utilized for the three different self-management behaviors.

Targeting of specific behaviors in self-management approaches may explain heterogeneity in effectiveness. Our review found SMIs that tackle mental health concerns are more effective than those aimed directly at respiratory health. Management of mental health problems is acknowledged as an important part of COPD care as comorbid mental health problems are common in COPD, with an estimated prevalence of 10%–42% for depression and 10%–60% for anxiety.Citation63–Citation66 However, fewer than 30% of treatment providers adhere to current guidance for management of anxiety and depression in COPD.Citation67,Citation68 The nature and direction of the relationship between mental health and respiratory symptoms in COPD are difficult to disentangle.Citation69 Breathlessness may be a symptom of anxiety or COPD, and in turn, deteriorating respiratory health may trigger anxiety;Citation64 and anxiety is associated with more frequent hospital admissions for exacerbations.Citation69 It follows that SMIs targeting mental health have the potential to improve HRQOL. Overall, few of the identified SMIs contained BCTs that targeted mental health self-management, although the six SMIs with the highest effect sizes utilized BCTs that targeted mental health concerns (). The most commonly reported BCT to aid management of mental health was input to “reduce negative emotions.” Interventions using this technique may improve patients’ self-efficacy for managing their symptoms, which could reduce the likelihood of attending ED’s at the onset of an exacerbation.Citation70 Alternatively, addressing mental health management may have an indirect effect in preventing a deterioration in clinical status by an improvement in mood, leading to greater willingness to engage in other preventative behaviors (eg, increased physical activity, medication adherence, improved nutritional diet).Citation71

In both moderator analysis and within-group analyses, SMIs targeting physical activity did not demonstrate a greater improvement in HRQOL compared with SMIs that did not target physical activity. It is surprising that the effect was not stronger, as patients engaging in increased physical activity are less likely to experience deterioration in physical condition and acute exacerbation.Citation66,Citation72 In contrast, physical deconditioning and inactivity may lead to faster deterioration in clinical status and increase the likelihood of hospital admission.Citation64,Citation66 Zwerink et alCitation7 also reported no improved benefit in SMIs that targeted physical activity. Furthermore, highlights the wide variability in BCTs that were used when targeting physical activity; with interventions ranging from individualized, structured, supervised sessions to education on physical activity. It is important when reporting SMIs that target physical activity that authors are clear about what is being asked of the patient. The American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society’s joint summary identifies physical activity outcomes as a priority for future research.Citation6 The summary states that determining the optimal level of instruction is a priority in design of future physical activity interventions (eg, how many sessions, over what time period, and what specific exercises). However, it is important to consider that an individually tailored approach is needed for patients with COPD where there is wide variability in capability and resources.

The most commonly identified BCTs varied for the three separate behaviors. Those coded for symptom management and physical activity were similar in that they used BCTs centered on information provision (eg, “Instruction on how to perform the behavior,” “Information about health consequences,” “Demonstration of the behavior”), whereas those coded for management of mental health concerns encourage more awareness and reflective thought processes (eg, “reduce negative emotions,” “monitoring of emotional consequences”). It is possible that SMIs that targeted mental health management routinely displayed larger effect sizes as a consequence of the type of BCTs rather than the behavior targeted. Further research should attempt to disentangle the extent to which it is specific BCTs, or the behavior targeted, that is responsible for the intervention effect.

One recommendation from the recent HTA review on SMIs was that “Novel approaches to influence behavior change … should be explored”.Citation8 Our approach identifies that vast majority of potential BCTs in the taxonomy were not identified across studies, suggesting opportunities for novel intervention content. For instance, it was apparent that while SMIs targeting mental health were more effective in improving HRQOL (eg, “reduce negative emotions”), the BCTs employed in these studies were not those recommended in current guidance as core strategies of self-management for COPD (eg, goal setting, problem solving, action planning).Citation2,Citation6 Similarly, while action planning is seen as a key component of effective self-management,Citation2,Citation6–Citation8 some theoretical models specify that action planning is not always sufficient for behavior change and that problem solving is required to effectively maintain behavior change.Citation71 As COPD is characterized by frequent relapses in the form of acute exacerbations, it was surprising that the BCT “problem solving” was only coded in two studies (). Future SMIs need to incorporate how to deal with problem solving as coping with the repeated occurrences of breathlessness and exacerbations (and the associated anxiety of these symptoms arising) is an inevitable predictor of HRQOL.Citation72

Intervention providers should look at how they can deliver the core strategies of self-management (eg, goal setting, problem solving) in ways that work across multiple behaviors rather than feeling certain BCTs are only applicable to single behaviors (eg, action planning can only be used for symptom management but not when explaining physical activity). For instance, “body changes” referred to breathing/relaxation techniques. This was often used for a specific behavior, but patients may have better outcomes if they understand how breathing/relaxation techniques can be used for managing breathlessness, reducing stress, and improving lung capacity when physically active. Explaining how the same behavior can be applied across situations may also be a more understandable message for patients with poor health literacy, rather than them believing that certain behavioral techniques can only be applied in certain contexts, especially when elevated anxiety may impair cognitive processing of the most suitable course of action. Furthermore, from an implementation perspective, SMIs employing multidisciplinary teams for individual-based interventions did not confer any significant increase in effect size. This is an important finding for clinical practice as single practitioner and group-based interventions are potentially of lower cost as multiple patients can be seen in a single setting.Citation73

An interesting finding from the narrative synthesis is that the number of eligible studies in Jonkman et al’sCitation10,Citation11 reviews and Zwerink et alCitation7 was approximately double the number found in the other reviews. The majority of additional studies in these reviews were recent publications. This may suggest that the use of SMIs has increased in less than a decade. However, further inspection of the definitions highlight where disparities between previous reviews may exist. Walters et alCitation36 only allowed single component (action plans) interventions and found no effect, whereas Zwerink et alCitation7 and Jonkman et alCitation10 both found a significant effect but stipulated that SMIs had to have at least two components (eg, action plans, symptom monitoring, physical activity component, etc.). This review highlights how the definition of SMI directly influences whether an effect is found on HRQOL.

A number of the reviews attempted to summarize components of their contributing SMIs, but these were often limited in description and were often a mixture of BCTs (eg, problem solving, action planning) and target behaviors (eg, mental health, physical activity). Zwerink et alCitation7 and Jonkman et alCitation10 were the only reviews to conduct subgroup analyses to quantify what content of SMIs are most effective. Zwerink et alCitation7 attempted to look at SMIs that did and did not utilize action plans, exercise programs, and behavioral components. However, the definitions for each of these three subgroup analyses were ambiguous: 1) action plans had to focus on symptom management, and thus excludes action planning techniques when the target behavior is physical or mental health, 2) focusing on only standardized exercise programs neglects the ways physical activity may be encouraged in everyday life (eg, energy conservation techniques), and 3) the authors themselves state that “behavioral components” was “difficult to determine because of lack of detailed information”. Jonkman et al’sCitation11 subgroup analyses were based on the absence/presence of clear BCTs: management of psychological aspects, goal setting skills, self-monitoring logs, and problem-solving skills. However the authors 1) combined a number of chronic conditions (COPD, chronic heart failure, and Type 2 diabetes) and 2) did not differentiate between the individual BCTs and the target behaviors. To build upon these authors’ previous work, we have used a standardized taxonomy with definitions for a wider array of BCTs and been more specific about the behavior the BCT is targeting. This allows better comparison of intervention content across studies and a more robust basis for synthesis. Ultimately, the increasing popularity and awareness of SMIs, but an increasing variation in definition, indicates a need for more structured guidance on what constitutes self-management so that both practitioners and patients are aware of what the content of self-management entails.

Strengths and limitations

Comparing the findings across reviews highlights how the definition of self-management had a direct impact on the number of eligible studies and consequently the conclusions drawn. The difference in conclusions further highlights the need for more detailed content analysis. The current analysis extracted robust empirical data from across reviews and their contributing clinical trials to examine intervention content and structure to isolate what factors may be essential for improving patient outcomes. The use of a standardized taxonomy of definitions allowed comparisons of intervention content across studies and provided a robust basis for synthesis. Our approach also highlighted specific BCTs used in a range of contexts to enable more discernment between intervention features and outcome effectiveness. We used a concise search strategy in order to identify individual trial data and perform novel forms of exploratory analysis that examined the effectiveness of individual intervention components. For this exploratory analysis, small and hard to find trials are unlikely to introduce components that do not occur in a range of other trials, and as such it is unnecessary to carry out an exhaustive search to identify all existing trials. However, it is important to stress that while we present a comprehensive summary of SMIs that have been reported in previous reviews, this review does not aim to present the most up-to-date evidence base as a number of more recent SMI trials will not have been captured in these reviews.

There are limitations to the study worth noting. The limited number of studies meant that single rather than multiple variables were entered into the moderator analyses. For example, we could compare single vs multiple session SMIs or individual vs group SMIs but could not examine combinations of the different variables in a multivariate analysis. Thus, while these univariate analyses can helpfully guide intervention development by highlighting potential associations, they should not be interpreted in an additive fashion. Furthermore, meta-regression findings do not imply causality, as factors entered into these analyses were not randomized groups in the analyses.

It was difficult to ascertain the intensity with which some BCTs were administered and the same BCT could be used with varying intensity, eg, the instructors could provide “Feedback on the behavior” on a daily or monthly basis. Ultimately, the utility of this secondary analysis is dependent on the reporting of intervention content by authors. It is possible that some BCTs were present in interventions, but not described in sufficient detail to allow coding. While we coded intervention manuals where available, there is a need for more transparency in intervention content in future studies.

Conclusion

SMIs can improve HRQOL and reduce the number of ED visits for patients with COPD, but there is wide variability in effect. To be effective, future interventions should focus on tackling mental health concerns but need not entail multidisciplinary and individual-focused SMIs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Capability Funding from Newcastle Gateshead Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG).

Supplementary material

Three reviews were discussed for eligibility. A review by Walters et alCitation1 focused upon studies where the intervention could be defined as

[…] use of guidelines detailing self-initiated interventions (eg, changing medication regime […]) which were undertaken in response to alterations in the state of the patients’ COPD (eg, increase in breathlessness) […]. An educational component was permitted if the duration was short, up to 1 hour.Citation1

In contrast, the focus of Jolly et al’s reviewCitation7 was “self-management” interventions, but the number of interventions included far exceeded the number of studies commonly found in the other eligible reviews and many would not typically be considered self-management (eg, structured pulmonary rehabilitation programs). As it was not possible to identify those that were primarily self-management based, we excluded this review as it summarizes evidence of a wider array of interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than self-management interventions.

Jonkman et alCitation8 highlighted relevant studies in the search, but the focus of the analysis was on an individual patient data analysis and as such the overall findings are not relevant to the current narrative.

References

- WaltersJATurnockACWaltersEHWood-BakerRAction plans with limited patient education only for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20105CD00507420464737

- JordanREMajothiSHeneghanNRSupported self-management for patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence synthesis and economic analysisHealth Technol Assess201519361516

- BlackstockFWebsterKEDisease-specific health education for COPD: a systematic review of changes in health outcomesHealth Ed Res2007225703717

- HarrisonSLJanaudis-FerreiraTBrooksDDesveauxLGoldsteinRSSelf-management following an acute exacerbation of COPD: a system atic reviewChest2015147364666125340578

- MajothiSJollyKHeneghanNRSupported self-management for patients with COPD who have recently been discharged from hospital: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20151085386725995625

- MonninkhofEvan der ValkPDVan der PalenJVan HerwaardenCPartridgeMRZielhuisGSelf-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewThorax200358539439812728158

- JollyKMajothiSSitchAJSelf-management of health care behaviors for COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20161130526937183

- JonkmanNHWestlandHTrappenburgJCCharacteristics of effective self-management interventions in patients with COPD: individual patient data meta-analysisEur Respir J2016481556827126694

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WedzichaJADonaldsonGCExacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Care2003481204121314651761

- National Clinical Guideline CentreChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Adults in Primary and Secondary CareLondonNational Clinical Guideline Centre2010 Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/EnglishAccessed on February 16, 2016

- British Lung FoundationInvisible Lives: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Finding the Missing MillionsLondonBritish Lung Foundation2007

- CoventryPAHindDComprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation for anxiety and depression in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisJ Psychosom Res20076355156517980230

- BaraniakASheffieldDThe efficacy of psychologically based interventions to improve anxiety, depression and quality of life in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysisPatient Educ Couns201183293620447795

- SpruitMASinghSJGarveyCAn official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20131888e13e6424127811

- ZwerinkMBrusse-KeizerMvan der ValkPDSelf-management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD00299024665053

- JordanREMajothiSHeneghanNRSupported self-management for patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence synthesis and economic analysisHealth Technol Assess201519361516

- MichieSRichardsonMJohnstonMThe behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventionsAnn Behav Med201346819523512568

- JonkmanNHSchuurmansMJGroenwoldRHHoesAWTrappenburgJCIdentifying components of self-management interventions that improve health-related quality of life in chronically ill patients: systematic review and meta-regression analysisPatient Educ Couns20169971087109826856778

- JonkmanNHWestlandHTrappenburgJCCharacteristics of effective self-management interventions in patients with COPD: individual patient data meta-analysisEur Respir J2016481556827126694

- CADTH filter Available from: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidenceAccessed January 25, 2017

- Spriometry for health care providersGlobal Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), 2010Accessed on January 25, 2017 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Spirometry_2010.pdf

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMThe St George’s respiratory questionnaireRespir Med19918525311759018

- WeldamSWSchuurmansMJLiuRLammersJWEvaluation of Quality of Life instruments for use in COPD care and research: a systematic reviewInt J Nurs Studies2013505688707

- Rutten-van MölkenMRoosBVan NoordJAAn empirical comparison of the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ) in a clinical trial settingThorax199954995100310525558

- Van der MolenTWillemseBWSchokkerSDevelopment, validity and responsiveness of the clinical COPD questionnaireHealth Qual Life Outcomes200311312773199

- BergnerMBobbittRACarterWBGilsonBSThe sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measureMed Care19817878057278416

- HajiroTNishimuraKTsukinoMIkedaAKoyamaHIzumiTComparison of discriminative properties among disease-specific questionnaires for measuring health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981577857909517591

- StällbergBNokelaMEhrsPOHjemdalPJonssonEWValidation of the clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) in primary careHealth Qual Life Outcomes200972619320988

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMA self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation: the St. George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireAm Rev Respir Dis1992145132113271595997

- TsiligianniIGvan der MolenTMoraitakiDAssessing health status in COPD. A head-to-head comparison between the COPD assessment test (CAT) and the clinical COPD questionnaire (CCQ)BMC Pulm Med2012122022607459

- DavidsonKWGoldsteinMKaplanRMEvidence-based behavioral medicine: what is it and how do we achieve it?Ann Behav Med20032616117114644692

- Department of HealthAn Outcomes Strategy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and Asthma in EnglandLondonDepartment of Health2011

- HoogendoornMRutten-van MölkenMPHoogenveenRTAlMJFeenstraTLDeveloping and applying a stochastic dynamic population model for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseValue Health20111481039104722152172

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0The Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.orgAccessed January 25, 2017

- HozoSDjulbegovicBHozoIEstimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sampleBMC Med Res Methodol200551315840177

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJErlbaum1988

- AdamsSGSmithPKAllanPFAnzuetoAPughJACornellJESystematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and managementArch Int Med2007167655156117389286

- BentsenSBLangelandEHolmALEvaluation of self-management interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Nurs Management2012206802813

- BlackstockFWebsterKEDisease-specific health education for COPD: a systematic review of changes in health outcomesHealth Ed Res2007225703717

- BourbeauJDisease-specific self-management programs in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseDis Management Health Outcomes2003115311319

- HarrisonSLJanaudis-FerreiraTBrooksDDesveauxLGoldsteinRSSelf-management following an acute exacerbation of COPD: a systematic reviewChest2015147364666125340578

- MajothiSJollyKHeneghanNRSupported self-management for patients with COPD who have recently been discharged from hospital: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20151085386725995625

- MonninkhofEvan der ValkPDVan der PalenJVan HerwaardenCPartridgeMRZielhuisGSelf-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewThorax200358539439812728158

- WaltersJATurnockACWaltersEHWood-BakerRAction plans with limited patient education only for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20105CD00507420464737

- BourbeauJulienMMaltaisFReduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management interventionArch Int Med200316358559112622605

- WatsonPBTownGIHolbrookNDwanCToopLJDrennanCJEvaluation of a self-management plan for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Resp J19971012671271

- GallefossFBakkePSRSGAARDPKQuality of life assessment after patient education in a randomized controlled study on asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med199915981281710051255

- EmeryCFScheinRLHauckERMacIntyreNRPsychological and cognitive outcomes of a randomized trial of exercise among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth Psychol1998172329619472

- Garcia-AymerichJHernandezCAlonsoAEffects of an integrated care intervention on risk factors of COPD readmissionResp Med200710114621469

- MonninkhofEVan der ValkPSchermerTVan der PalenJVan HerwaardenCZielhuisGEconomic evaluation of a comprehensive self-management programme in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChron Resp Dis20041716

- BucknallCEMillerGLloydSMGlasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trialBMJ2012344e106022395923

- LittlejohnsPBaveystockCMParnellHJonesPWRandomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of a respiratory health worker in reducing impairment, disability, and handicap due to chronic airflow limitationThorax19914685595641926024

- Wood-BakerRMcGloneSVennAWaltersEHWritten action plans in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increase appropriate treatment for acute exacerbationsRespirology20061161962616916336

- CoultasDFrederickJBarnettBSinghGWludykaPA randomized trial of two types of nurse-assisted home care for patients with COPDChest20051282017202416236850

- HermizOCominoEMarksGDaffurnKWilsonSHarrisMRandomised controlled trial of home based care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBMJ200232593812399344

- KhdourMRKidneyJCSmythBMMcElnayJCClinical pharmacy-led disease and medicine management programme for patients with COPDBrit J Clin Pharmacol20096858859819843062

- McGeochGRWillsmanKJDowsonCASelf-management plans in the primary care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology20061161161816916335

- NinotGMoullecGPicotMCCost-saving effect of supervised exercise associated to COPD self-management education programResp Med2011105377385

- RiceKLDewanNBloomfieldHEDisease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med201018289089620075385

- WakabayashiRMotegiTYamadaKEfficient integrated education for older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using the Lung Information Needs QuestionnaireGeriatr Gerontol Int20111142243021447136

- BischoffEWAkkermansRBourbeauJvan WeelCVercoulenJHSchermerTRComprehensive self management and routine monitoring in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in general practice: randomised controlled trialBMJ2012345e764223190905

- FanVSGazianoJMLewRA comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizationsAnn Intern Med201215753053123027327

- KoffPBJonesRHCashmanJMVoelkelNFVandivierRWProactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPDEur Resp J20093310311038

- TaylorSJSohanpalRBremnerSASelf-management support for moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot randomised controlled trialBr J Gen Pract201262e687e69523265228

- TrappenburgJCMonninkhofEMBourbeauJEffect of an action plan with ongoing support by a case manager on exacerbation-related outcome in patients with COPD: a multicentre randomised controlled trialThorax20116697798421785156

- ZwarNAHermizOCominoECare of patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cluster randomised controlled trial

- FaulknerJWalshawECampbellJThe feasibility of recruiting patients with early COPD to a pilot trial assessing the effects of a physical activity interventionPrim Care Respir J20101912413020126968

- KheirabadiGRKeypourMAttaranNBagherianRMaracyMREffect of add-on “Self management and behavior modification” education on severity of COPDTanaffos200872330

- MoullecGNinotGAn integrated programme after pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on emotional and functional dimensions of quality of lifeClin Rehabil20102412213620026578

- RootmensenGNvan KeimpemaARLooysenEEvan der SchaafLde HaanRJJansenHMThe effects of additional care by a pulmonary nurse for asthma and COPD patients at a respiratory outpatient clinic: results from a double blind, randomized clinical trialPatient Educ Couns200870217918618031971

- BlakemoreADickensCGuthrieEDepression and anxiety predict health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201420501512

- Heslop-MarshallKDe SoyzaAAre we missing anxiety in people with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)?Ann Depress Anxiety201411023

- MaurerJRebbapragadaVBorsonSACCP Workshop Panel on Anxiety and Depression in COPDAnxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needsChest200813443S56S18842932

- DowsonCATownGIFramptonCPsychopathology and illness beliefs influence COPD self-managementJ Psychosom Res20045633334015046971

- NaylorCParsonageMMcDaidDLong-Term Conditions and Mental Health: The Cost of Co-morbiditiesLondonThe King’s Fund and Centre for Mental Health2012

- van EdeLYzermansCJBrouwerHJPrevalence of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewThorax19995468869210413720

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJDepression and anxiety in elderly outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, and validation of the BASDEC screening questionnaireInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2000151090109611180464

- SimpsonEJonesMCAn exploration of self-efficacy and self-management in COPD patientsBr J Nurs2013221105110924165403

- RhodesREYaoCAModels accounting for intention-behavior discordance in the physical activity domain: a user’s guide, content overview, and review of current evidenceInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act201512925890238

- EstebanCQuintanaJMMorazaJImpact of hospitalisations for exacerbations of COPD on health-related quality of lifeRespir Med20091031201120819272762

- GlickHADoshiJASonnadSSPolskyDEconomic Evaluation in Clinical TrialsOxfordOxford University Press2014