Abstract

Objective

Anxiety and depression are highly prevalent in patients with COPD and their informal carers, and associated with numerous risk factors. However, few studies have investigated these in primary care or the link between patient and carer anxiety and depression. We aimed to determine this association and factors associated with anxiety and depression in patients, carers, and both (dyads), in a population-based sample.

Materials and methods

This was a prospective, cross-sectional study of 119 advanced COPD patients and their carers. Patient and carer scores ≥8 on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale defined symptoms of anxiety and depression, χ2 tests determined associations between patient and carer symptoms of anxiety/depression, and χ2 and independent t-tests for normally distributed variables (otherwise Mann–Whitney U tests) were used to identify other variables significantly associated with these symptoms in the patient or carer. Patient–carer dyads were categorized into four groups relating to the presence of anxious/depressive symptoms in: both patient and carer, patient only, carer only, and neither. Factors associated with dyad symptoms of anxiety/depression were determined with χ2 tests and one-way analysis of variance for normally distributed variables (otherwise Kruskal–Wallis tests).

Results

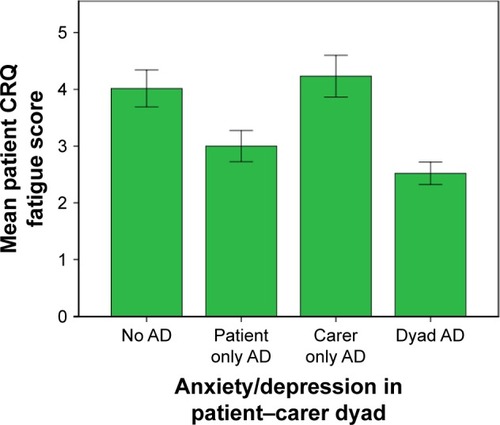

Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression was 46.4% (n=52) and 42.9% (n=48) in patients, and 46% (n=52) and 23% (n=26) in carers, respectively. Patient and carer symptoms of anxiety/depression were significantly associated. Anxious and depressive symptoms in the patient were also significantly associated with more physical comorbidities, more exacerbations, greater dyspnea, greater fatigue, poor mastery, and depressive symptoms with younger age. Symptoms of carer anxiety were significantly associated with being female and separated/divorced/widowed, and depressive symptoms with younger age, higher educational level, and more physical comorbidities, and symptoms of carer anxiety and depression with more unmet support needs, greater subjective caring burden, and poor patient mastery. Dyad symptoms of anxiety/depression were significantly associated with greater patient fatigue.

Conclusion

Symptoms of anxiety and depression in COPD patients and carers are significantly associated. Given their high prevalence, considerable impact on mortality, impact on quality of life and health care use, and associations with each other, screening for and addressing patient and carer anxiety and depression in advanced COPD is recommended.

Plain language summary

Anxiety and depression are very common in patients with COPD and family or friends who provide care and support (carers). We wanted to find out whether these psychological health problems in patients and carers were linked and what the risk factors are for patients, carers, or both being anxious or depressed. Knowing these might help us target patients and carers most at risk and improve the management of psychological health in COPD. We collected information from 119 patients with advanced COPD and their carers. Up to 40% of these patients and carers had symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Anxious and depressed patients were more likely to have anxious and depressed carers. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were more common in patients who were more symptomatic and those with poor control of their lung problem and other physical health problems. Symptoms of depression alone were found more in patients who were younger. More anxious carers were female and separated and divorced or widowed, and more depressed carers were younger, more highly educated, and had physical health problems themselves. Carers who were either more anxious or depressed had more unmet support needs, felt they had a higher caring burden, and had patients with less control of their lung problem. Symptoms of anxiety or depression in both a patient and their carer were linked to patient fatigue. Our results suggest that it is important to screen for and address anxiety and depression not only in patients with COPD but also carers, especially of patients with anxiety or depression.

Introduction

Anxiety and depression are common in COPD, with reported prevalence ranges of 10%–55% and 7%–42%, respectively.Citation1–Citation3 They decrease treatment adherence and are associated with higher mortality,Citation2–Citation4 poorer health-related quality of life,Citation1–Citation8 and increased hospital admissions.Citation2,Citation3,Citation9 Previous studies have identified numerous risk factors for anxiety and depression in patients, including younger age,Citation4,Citation7,Citation8,Citation10 being female,Citation4,Citation5,Citation8,Citation10 living alone,Citation6 current smoking,Citation2–Citation4,Citation8,Citation10 and comorbidities.Citation3,Citation4 Poor psychological health preferentially coexists with frequent exacerbations,Citation4,Citation8,Citation9 dyspnoea,Citation4,Citation5,Citation8,Citation10–Citation12 fatigue,Citation4 impaired physical functioning and reduced exercise capacity,Citation2–Citation4,Citation6,Citation8,Citation10 and low self-efficacy.Citation2,Citation9

As COPD progresses and becomes advanced, patients become increasingly dependent on informal carers (family members or friends). Anxiety and depression are known to be as prevalent in carers as in patients, with up to 63% reporting clinically significant anxiety symptoms and 51% reporting depressive symptoms.Citation13,Citation14 Older age,Citation13,Citation15,Citation16 being female,Citation13,Citation15,Citation17,Citation18 and spousal patient–carer relationshipCitation13,Citation14 have been associated with carer psychological morbidities. Low educational level,Citation13,Citation16 lack of support,Citation19,Citation20 and poor carer healthCitation18 are also risk factors, as are disease factors such as severity,Citation13–Citation15 exacerbations,Citation20 and dyspnea.Citation13,Citation14 Subjective carer burden (carer’s appraisal of the impact of the role on their health, social and occupational life, finances, and reactions to caring)Citation13–Citation15,Citation18,Citation21 has been significantly associated with anxiety and depression, but the evidence for objective carer burden (such as time spent caregiving) is mixed.Citation13,Citation14,Citation21

However, the majority of studies have investigated psychological health in secondary-care cohorts (eg, patients admitted to hospital for exacerbations), which does not represent the whole population of people living with advanced COPD.Citation14,Citation18,Citation19 Few studies have been conducted in the primary-care setting.Citation7 Also, while they have been studied separately, less is known about the association between patient and carer anxiety and depression, and factors associated with both patient and carer anxiety and depression in the dyad are unknown. We aimed to determine the association between patient and carer anxiety and depression and factors associated with anxiety and depression in patients, carers, and both in the dyad in a population-based cohort, sampled from primary care.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was an analysis of data from patients and carers who participated in baseline interviews for the longitudinal interview-study component of the larger prospective Living with Breathlessness study.Citation22 In the longitudinal interview study, 652 patients with advanced COPD were identified by 63 primary-care practices in the east of England and mailed a recruitment pack: 248 patients agreed to participate, of whom 235 consented and participated (36% participation rate). Targeting of practice types maximized their variability to achieve representativeness. Patients with well-characterized advanced COPD were recruited, who met at least two of six inclusion criteria: forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) <30%, two or more exacerbations requiring prednisolone or antibiotics in the previous year, one or more hospital admission for COPD in the previous 2 years, long-term oxygen therapy, cor pulmonale and Medical Research Council dyspnea scale score ≥4. Exclusion criteria were serious mental health problem, serious learning difficulty, active cancer, and active alcoholism. Patients were asked to identify their primary informal carer, who was also invited to participate. Carer-exclusion criteria were under 18 years of age and unable to give informed consent; 119 carers consented and effectively participated (51% participation rate). The study received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee East of England – Cambridge South (12/EE/0163). All participants gave written informed consent.

Data collection

Data were collected during face-to-face interviews with patients and carers in their home setting. Interviews with patients and carers were conducted separately wherever possible; occasionally, the physical layout of the home made separate interviews impossible. Sociodemographics and clinical characteristics of participants were obtained. Data on the caring situation (patient–carer kin relationship, cohabitation, duration of caring, and hours of caring per week) were also collected. Patients completed the 20-item Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ; self-administered standardized version)Citation23 to measure disease-specific health-related quality of life: items scored on a 7-point scale contribute to four subdomains of dyspnea, fatigue, emotional function, and mastery (how in control the patient feels of their condition), each scored 0–7, with higher scores indicating better health-related quality of life. Carers rated subjective caring burden on the Family Appraisal of Caregiving Questionnaire – palliative care, addressing caregiver strain (feelings of fatigue, isolation, lack of control, negative impact on own health, social life, occupational life, and finances), caregiver distress (anxiety and depression), and positive caregiving appraisals (commitment, satisfaction, stronger relationship), with each statement scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strong agreement to strong disagreement.Citation24 Carers identified unmet support needs with the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool, which covers 14 support domains in two groupings of support to enable the carer to provide care for the patient (eg, managing symptoms, including giving medicines) and direct support for carers’ own health and well-being (eg, dealing with feelings and worries), with the need for more support indicated on a 4-point categorical scale from 0 (none) to 3 (very much more).Citation25 Patient and carer psychological health was assessed with the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a well-validated and reliable self-report screening tool for symptoms of anxiety and depression, which is analyzed as two separate 7-item subscales for anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D), each with a total score of 0–21.Citation26 Of the 119 patients who had a participating carer, 112 patients completed the HADS questionnaire; of the 119 carers, 113 carers provided responses to the questionnaire. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were defined as HADS-A and HADS-D score ≥8, the commonly used threshold for mild symptoms of anxiety and depression.Citation27

Statistical analysis

To determine associations between patient and carer symptoms of anxiety and depression, χ2 tests were used; χ2 and independent t-tests for normally distributed variables (otherwise Mann–Whitney U tests) were used to identify other variables significantly associated with anxious or depressive symptoms in the patient or carer. Dyads were then categorized into four groups relating to the presence of anxious or depressive symptoms: both patient and carer, patient only, carer only, and neither. Factors significantly associated with symptoms of anxiety or depression in both (dyad symptoms of anxiety or depression) were determined with χ2 tests and one-way analysis of variance (with Bonferroni post hoc tests) for normally distributed variables (otherwise Kruskal–Wallis tests). Statistical significance was set at P≤0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The mean age (±SD) of patients and carers was 71.4±8.7 years and 64.2±14.5 years; 39.3% of patients and 72.6% of carers were female. The prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression was 46.4% (n=52) and 42.9% (n=48) in patients, and 46% (n=52) and 23% (n=26) in carers, respectively. Symptoms of patient anxiety were significantly associated with carer anxiety (χ2=6.475, P=0.011) and depression (χ2=3.86, P=0.049). Symptoms of patient depression were also significantly associated with both carer anxiety (χ2=6.249, P=0.012) and depression (χ2=11.032, P=0.011). Additional factors associated with patient and carer anxious and depressive symptoms are shown in and .

Table 1 Factors associated with symptoms of patient anxiety and depression

Table 2 Factors associated with symptoms of carer anxiety and depression

Symptoms of patient depression were significantly associated with younger age, and symptoms of anxiety and depression with each other, more patient physical comorbidities, more exacerbations at home, greater dyspnea, greater fatigue, and poor mastery. Symptoms of carer anxiety were associated with being female and separated/divorced/widowed, symptoms of depression with younger age, higher educational level, and more carer physical comorbidities, and symptoms of anxiety and depression with each other, more unmet support needs, greater subjective caring burden, and poor patient mastery.

The number of dyads in which both patient and carer had symptoms of anxiety or depression was 37, in which only the patient had these symptoms 28, in which only the carer had these symptoms 15, and in which neither had these symptoms 29. Dyad symptoms of anxiety or depression were significantly associated with lower mean patient CRQ fatigue score (representing higher fatigue) compared to dyads in which only the patient (2.5 vs 3, P=0.049), the carer (2.5 vs 4.2, P<0.0005), or neither (2.5 vs 4, P<0.0005) had symptoms of anxiety or depression ().

Figure 1 Dyad symptoms of anxiety or depression associated with patient fatigue. Notes: No AD (n=29), patient only AD (n=28), carer only AD (n=15), dyad AD (n=37). Data analyzed with one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show that symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients and carers living with advanced COPD are significantly associated with each other in a population-based sample. One mechanism for this may be emotional contagion, where individuals in close relationships mimic each other’s emotions (seen in facial expressions), with stronger associations in more severe distress.Citation28

It is possible to interpret these findings within Rolland’s family-systems illness model to help our understanding.Citation29–Citation32 The relapsing unpredictable disease course of COPD may be particularly taxing for families to adjust to, resulting in substantial psychological incongruity between periods of chronic disease and relapse, and anticipatory anxiety. There is also the risk of families coming together to deal with exacerbations and hospital admissions, but remaining “enmeshed”, which may be maladaptive in the chronic phase of COPD, leading to family burnout and permanent distortion of the patient–family relationship. As the patients in our study had advanced COPD, families may also have been living in the terminal phase, with issues of loss and need for family reorganization. Taken together, these factors may contribute to the high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in both the patient and carer cohorts.

Patient depression was significantly associated with younger age, possibly due to greater difficulty adjusting to disease limitations.Citation7,Citation10 The link between exacerbations, dyspnea and anxiety may be explained by the dyspnea–anxiety–dyspnea cycleCitation11 and cognitive model of panic,Citation12 a catastrophic misinterpretation of the sensation of dyspnea, possibly due to chemoreceptor hypersensitivity to CO2 or processing of the affective dimension of dyspnea and anxiety in common neuroanatomical regions.Citation1,Citation12 Interestingly, anxiety was only associated with exacerbations at home (not requiring hospital admission), which may support the hypothesis of overinterpretation of dyspneaCitation9 or reflect higher anxiety from managing exacerbations in a nonclinical environment. There is evidence that systemic inflammation in exacerbations, with elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein, leads to depressive symptoms.Citation33 Inversely, anxiety and depression can increase the risk of exacerbations, through hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activation suppressing immune function.Citation9 Anxiety and depression were also associated with fatigue and more physical comorbidities, which may be because these lead to physical inactivity, social isolation, and thus depression. Psychological morbidities may impair the ability to acquire skills and lower confidence in self-management, leading to poor mastery.Citation3,Citation9 Finally, greater subjective symptom burden (CRQ scores) were significantly associated with anxiety and depression, but objective disease severity (% predicted FEV1) was not.

Being female was strongly associated with carer anxiety, in concordance with previous studies.Citation13,Citation15,Citation17,Citation18 Women may use more emotion-based coping strategies, or view the caregiving role negatively as a continuation of their sex role.Citation13,Citation17 The number of unmet carer-support needs had a robust association with carer anxiety and depression; the link between anxiety and carers being separated/divorced/widowed may also be related to lack of social support for the carer. Carers with depression were younger and of higher educational level, which (as with patients) may be due to difficulty adjusting to forced changes in lifestyle with the caring role, which would be greater for carers having their own physical comorbidities. Finally, anxiety and depression were significantly associated with greater subjective caring burden and anxiety with poor mastery by the patient (which could increase carer burden).

Importantly, we found that dyad anxiety or depression was significantly associated with greater patient fatigue. This may be explained by fatigue diminishing patient capacity to perform activities of daily living, thus increasing carer burden and reducing patients’ sense of independence, leading to psychological morbidity in both. Conversely, psychological morbidity in either patient or carer may impact on capacity for patient activity, resulting in deconditioning and fatigue.

Within Rolland’s family-system illness model, the associations found between younger age and both patient and carer depressive symptoms may reflect the conflict between this chronic disease having a centripetal effect on the family (greater focus on internal family life) and a younger patient or carer being part of a family in a centrifugal period (which is when individual family members are more engaged in the extrafamilial environment). Living with advanced COPD as a patient or carer may necessitate sacrifices in personal autonomy, which can have profound permanent effects on the family life cycle. Additionally, advanced COPD usually occurs in late adulthood, when having or caring for illness is more expected: younger patients and carers may be in a life-structure-building/maintenance period and may be forced back into an “out of phase” transition period that is disruptive. This is especially the case for diseases with a relapsing course, where the constant state of readiness required maintains the family in an out-of-phase state. Carers who were separated, divorced, or widowed were more likely to have symptoms of anxiety. This may be because separation represents a life-structure-changing period. When illness is concurrent with this, it can have a long-lasting impact on preparation for the next period of the life cycle. Finally, the link between patient mastery and patient and carer symptoms of anxiety and depression may be explained by mastery of illness being a key belief in the family’s belief system, which may influence the family’s account of illness and their strategies to adapt.

Clinical implications

As disease severity itself is not a barrier to psychological health, it is important to identify and address anxiety and depression in patients with advanced COPD. This study shows that it is feasible to use a simple tool, such as the HADS, to screen for anxious and depressive symptoms in a clinical setting, which can indicate those who need more detailed assessment. Primary-care health professionals would be best placed to undertake this, to ensure coverage of the whole population of people living with advanced COPD. Clinicians should encourage all patients to participate in pulmonary rehabilitation, especially the exercise-training component, as this may represent the most effective way to interfere with the anxiety–dyspnea cycle.Citation34 Education for patients and carers on managing breathlessnessCitation35 and exacerbations may reduce the anxiety associated with exacerbations at home. Pulmonary rehabilitation could also be an opportunity to increase physical activity and social interactions, which may help to prevent depression. It is important that although patients have advanced COPD, clinicians appropriately manage (and do not neglect) comorbid physical conditions and do not attribute all symptoms to COPD.

Given their high prevalence and associations, it may be appropriate to screen carers (particularly of COPD patients with anxiety and depression) for anxiety and depression. Particular attention must be given to carers who are female, younger, separated, divorced, or widowed, who have physical medical conditions themselves, who report a higher caring burden or more unmet support needs, and who have patients who struggle to manage their own COPD. Possible interventions include enabling carers to participate in care planning to improve understanding of COPD, education for carers on symptom control, and inclusion of carers in pulmonary rehabilitation programs, to reduce unmet support needs of the carer.Citation35,Citation36 Patients and carers may need access to respite care, and carers need time to attend to their own health (including their own medical conditions), work, and social life. Given the link between patient mastery and carer anxiety and depression, supporting patients in self-management of COPD could reduce psychological morbidity in carers.

Regarding the relationship between dyad anxiety and depression and patient fatigue, patients and carers could be supported to optimize their delegated dyadic coping: carers could offer balanced social support (so that they do not become overwhelmed themselves) and encourage patients to do as many everyday activities as they are able to before becoming too fatigued (to maintain a degree of self-efficacy).Citation37

Strengths and limitations

Important strengths of this study were the prospective design and recruitment of a population-based cohort sampled from primary care (which is most representative of the whole population of patients living with advanced COPD). Patients typically receive shared care, with the majority of care being undertaken in primary care and the involvement of secondary care signifying either severe exacerbations or progressive symptoms (a distinct experience), which some with COPD do not experience. The patients in our cohort were well characterized in terms of their advanced COPD and sex-balanced. Research in COPD has historically focused on males, but females are increasingly affected by the condition, so are an important study group.

However the cross-sectional approach limited analyses to associations: longitudinal studies and analyses are needed to clarify the direction of causality and investigate changes in determinants of psychological health over time. The HADS is a self-report screening tool for symptoms of anxiety and depression, and not a formal physician diagnosis of anxiety or depression. Further, it asks about somatic symptoms that may equally be attributed to COPD. In addition, we did not control for any treatments for anxiety and depression that may have been received. Interviews with patients and carers were occasionally conducted together, where the physical layout of the home made separate interviews impossible. Previous studies have shown that combined and separate clinics with patients and carers in end-of-life care yield distinct findings. It has been shown that clinically, patients and carers value the time alone to voice their feelings and concerns, with patients expressing more cues that reveal emotion (surpassing the desire for information) and carers contributing more to conversation in private clinics.Citation38 Therefore, in joint interviews, it is possible patients and carers may have been more reluctant to express feelings of anxiety or depression. Nevertheless, the large majority of interviews were conducted separately, so we do not expect this to have significantly affected our results, but any effect would be an under- (rather than an over-) reporting of psychological morbidity in this population.

Conclusion

Symptoms of anxiety and depression of patients with advanced COPD and carers are significantly associated, and associated with younger age, female sex, being separated/divorced/widowed, higher educational level, poor physical health, greater disease and subjective caring burden, unmet carer-support needs, and poor patient self-efficacy. Dyad symptoms of anxiety or depression were associated with greater patient fatigue. Given their high prevalence, considerable impact on mortality, quality of life, health care service use, and their associations with each other, it is necessary to screen for and address anxiety and depression in patients and carers.

Author contributions

MF conceived and designed the study. GE, RM, SB, and HHB participated in conducting the study. MF and ACG acquired the data. Ella M and Emma M analyzed and interpreted the data. Ella M, Emma M, and MF drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approve the final version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Ella M and Emma M are siblings.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Silvia Mendonca for providing statistical support. The Living with Breathlessness Study program thanks: all participating patients, informal carers, and health care professionals; the former Primary Care Research Networks and all recruiting practices (East of England and South London); the British Lung Foundation Breathe Easy support groups and additional patient and carer representatives for their PPI (patient and public involvement) roles; Kevin Houghton for administrative support; Sam Barclay for additional data entry; and the program funders Marie Curie and the National Institute for Health Research. The Living with Breathlessness Study program is independent research supported by Marie Curie (grant C28845/A14129) and the National Institute for Health Research (grant CDF-2012-05-218). RM is supported by Cambridge National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health, or other funders. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WillgossTGYohannesAMAnxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic reviewRespir Care201358585886622906542

- HillKGeistRGoldsteinRSLacasseYAnxiety and depression in end-stage COPDEur Respir J200831366767718310400

- MaurerJRebbapragadaCBorsonSAnxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needsChest20081344 Suppl43S56S

- HananiaNAMüllerovaHLocantoreNWDeterminants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183560461120889909

- Di MarcoFVergaMReggenteMAnxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severityRespir Med2006100101767177416531031

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerFWIJzermansCJvan der ZeeJSSchadéERisk of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinantsThorax200257541241611978917

- ClelandJALeeAJHallSAssociations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patientsFam Pract200724321722317504776

- EisnerMDBlancPDYelinEHInfluence of anxiety on health outcomes in COPDThorax201065322923420335292

- LaurinCMoullecGBaconSLLavoieKLImpact of anxiety and depression on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation riskAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012185991892322246177

- SchaneREWalterLCDinnoACovinskyKEWoodruffPGPrevalence and risk factors for depressive symptoms in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Gen Intern Med200823111757176218690488

- BaileyPHThe dyspnea-anxiety-dyspnea cycle: COPD patients’ stories of breathlessness – “It’s scary/when you can’t breathe”Qual Health Res200414676077815200799

- SmollerJWPollackMHOttoMWRosenbaumJFKradinRLPanic anxiety, dyspnea, and respiratory disease: theoretical and clinical considerationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med199615416178680700

- JácomeCFigueiredoDGabrielRCruzJMarquesAPredicting anxiety and depression among family carers of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt Psychogeriatr20142671191119924621411

- Bernabeu-MoraRGarcía-GuillamónGMontilla-HerradorJEscolar-ReinaPGarcía-VidalJAMedina-MirapeixFRates and predictors of depression status among caregivers of patients with COPD hospitalized for acute exacerbations: a prospective studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016113199320528008245

- FigueiredoDGabrielRJácomeCCruzJMarquesACaring for relatives with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: how does the disease severity impact on family carers?Aging Ment Health201418338539324053489

- Al-GamalEYorkeJPerceived breathlessness and psychological distress among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spousesNurs Health Sci201416110311123692348

- NordtugBKrokstadSHolenAPersonality features, caring burden and mental health of cohabitants of partners with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or dementiaAging Ment Health201115331832621140302

- BadrHFedermanADWolfMRevensonTAWisniveskyJPDepression in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their informal caregiversAging Ment Health201721997598227212642

- BurtonAMSautterJMTulskyJABurden and well-being among a diverse sample of cancer, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caregiversJ Pain Symptom Manage201244341042022727950

- SpenceAHassonFWaldronMActive carers: living with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Palliat Nurs200814836837219023952

- GrantMCavanaghAYorkeJThe impact of caring for those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on carers’ psychological well-being: a narrative reviewInt J Nurs Stud201249111459147122386988

- University of Cambridge Department of Public Health and Primary CareLiving with Breathlessness study Available from: http://www.phpc.cam.ac.uk/pcu/research/research-projects-list/living-with-breath-lessness-studyAccessed June 20, 2016

- SchünemannHJGriffithLJaeschkeRA comparison of the original chronic respiratory questionnaire with a standardized versionChest200312441421142914555575

- CooperBKinsellaGJPictonCDevelopment and initial validation of a family appraisal of caregiving questionnaire for palliative carePsychooncology200615761362216287207

- EwingGBrundleCPayneSGrandeGThe carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation studyJ Pain Symptom Manage201346339540523245452

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand19836763613706880820

- BjellandIDahlAAHaugTTNeckelmannDThe validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature reviewJ Psychosom Res2002522697711832252

- GumpBBKulikJAStress, affiliation, and emotional contagionJ Pers Soc Psychol19977223053199107002

- RollandJSToward a psychosocial typology of chronic and life-threatening illnessFam Syst Med198423245263

- RollandJSChronic illness and the life cycle: a conceptual frameworkFam Process19872622032213595826

- RollandJSFamily illness paradigms: evolution and significanceFam Syst Med198754467486

- RollandJSBeliefs and collaboration in illness: evolution over timeFam Syst Health1998161–2727

- LuYFengLFengLNyuntMSYapKBNgTPSystemic inflammation, depression and obstructive pulmonary function: a population-based studyRespir Res2013145323676005

- EmeryCFScheinRLHauckERMacIntyreNRPsychological and cognitive outcomes of a randomized trial of exercise among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth Psychol19981732322409619472

- EwingGPenfoldCBensonJAClinicians’ views of educational interventions for carers of patients with breathlessness due to advanced disease: findings from an online surveyJ Pain Symptom Manage201753226527127725250

- FarquharMPenfoldCBensonJSix key topics informal carers of patients with breathlessness in advanced disease want to learn about and why: MRC phase I study to inform an educational interventionPLoS One2017125e017708128475655

- MeierCBodenmannGMörgeliHJeneweinJDyadic coping, quality of life, and psychological distress among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and their partnersInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011658359622135491

- SwetenhamKTiemanJButowPCurrowDCommunication differences when patients and caregivers are seen separately or togetherInt J Palliat Nurs2015211155756326619240