Abstract

Background

The systemic (extrapulmonary) effects and comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) contribute substantially to its burden. The supposed link between COPD and its systemic effects on distal organs could be due to the low-grade systemic inflammation. The aim of this study was to investigate whether the systemic inflammation may influence the skin condition in COPD patients.

Materials and methods

Forty patients with confirmed diagnosis of COPD and a control group consisting of 30 healthy smokers and 20 healthy never-smokers were studied. Transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, skin sebum content, melanin index, erythema index, and skin temperature were measured with worldwide-acknowledged biophysical measuring methods at the volar forearm of all participants using a multifunctional skin physiology monitor. Biomarkers of systemic inflammation, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), were measured in serum using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

Results

There were significant differences between COPD patients and healthy never-smokers in skin temperature, melanin index, sebum content, and hydration level (P<0.05), but not for transepidermal water loss and erythema index. No significant difference was noted between COPD patients and smokers in any of the biophysical properties of the skin measured. The mean levels of hsCRP and IL-6 in serum were significantly higher in COPD patients and healthy smokers in comparison with healthy never-smokers. There were significant correlations between skin temperature and serum hsCRP (R=0.40; P=0.02) as well as skin temperature and serum IL-6 (R=0.49; P=0.005) in smokers. Stratum corneum hydration correlated significantly with serum TNF-α (R=0.37; P=0.01) in COPD patients.

Conclusion

Differences noted in several skin biophysical properties and biomarkers of systemic inflammation between COPD patients, smokers, and healthy never-smokers may suggest a possible link between smoking-driven, low-grade systemic inflammation, and the overall skin condition.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of global morbidity and mortality and remains one of the greatest public health concerns.Citation1 Many patients with COPD have concomitant chronic diseases linked to the same risk factors, mainly smoking and aging. In addition to the pulmonary features of COPD, many of its systemic effects have been well recognized. More than 30% of COPD patients have one additional chronic disease and another 40% have two or more comorbidities.Citation2,Citation3 Inflammatory mediators in the circulation (the “spill-over” theory) may contribute to skeletal muscle wasting, cachexia, and may initiate or worsen common COPD comorbidities such as ischemic heart disease, heart failure, osteoporosis, anemia, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. These comorbidities result in impaired functional capacity, a decrease in quality of life, increased risk of hospitalizations, mortality, and significantly increased COPD-related healthcare costs.Citation4,Citation5 There is also a group of underrecognized COPD extrapulmonary manifestations, which include rhinosinusitis, dermatologic and ophthalmologic abnormalities, endocrinological disorders, or gastroesophageal reflux disease. These conditions may not always be fully recognized due to their relatively low clinical significance, data ambiguity, or inefficient mention in the literature.Citation6

Skin is a multifunctional organ in the body acting as a protective physical barrier by absorbing UV radiation, preventing microorganism invasion, chemical penetration, and controlling the passage of water and electrolytes. In addition, skin has a major role in thermoregulation of the body as well as complex immunological, sensory, and autonomic functions.Citation7

The data on skin condition in COPD are scarce. Studies confirm the association between smoking and premature aging of the skin. It has been shown that cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for the development of premature facial wrinklingCitation8–Citation10 and that facial wrinkling is associated with COPD in smokers, and both disease processes may share a common susceptibility.Citation11

The aim of this study was to compare the biophysical characteristics of the skin and serum levels of biomarkers of systemic inflammation in COPD subjects, healthy smokers, and never-smokers. In addition, we investigated whether skin condition in healthy smokers and COPD subjects is affected by systemic inflammation and whether it is linked to smoking.

Materials and methods

Study population

A total of 90 volunteers including a cohort of 40 COPD patients, 30 healthy smokers with a minimum of 10 pack-years history of smoking, and 20 healthy never-smokers were examined. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Lodz and was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles. All participants provided written informed consent before any study procedures were performed.

Methods

All study participants underwent clinical assessments including detailed medical history, physical examination, evaluation of biophysical skin variables, and spirometry. In addition, COPD subjects self-evaluated disease-specific symptoms with modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT). Physical capacity impairment was measured using the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). On the basis of available data, body mass index, airway obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (BODE) index for each of the COPD subjects was also calculated.

Biophysical skin properties

Transepidermal water loss (TEWL), stratum corneum hydration, skin sebum content, melanin index, erythema index, and skin temperature were measured at the volar forearm of all participants using a multifunctional skin physiology monitor (Courage & Khazaka electronic GmbH, Cologne, Germany). This multiprobe adapter system consists of respective probes: TEWAmeter, corneometer, sebumeter, mexameter, and skin thermometer. The measurement of TEWL by TEWAmeter® TM 300 is based on the diffusion in an open chamber and is measured as g/m2/h.Citation12 Corneometer® CM 825 uses the high dielectric constant of water for analyzing the water-related changes in the electrical capacitance of the skin. It provides hydration measurements in system-specific arbitrary units.Citation13 Sebumeter® SM 815 uses the difference of light intensity through a plastic strip to indicate the amount of absorbed sebum. The sebum level is expressed in µg/cm2.Citation14 Mexameter® MX 18 calculates melanin index from the strength of the absorbed and the reflected light at 660 and 880 nm, respectively, and similarly, erythema index at 568 and 660 nm, respectively.Citation15 Skin-Thermometer ST 500 was used to measure the skin temperature. The measurement is based on relative infrared temperature measurement.

All participants were asked to wash their hands with water only and not to use any soap or detergent or cosmetic products for at least 12 hours prior to measurements so that they would not affect measured biophysical skin parameters. Before skin measurements, participants rested for 30 minutes in a room with climate control having a temperature of 20°C–24°C and relative humidity of 30%–40% according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. The same trained investigator performed measurements of all skin variables between 8 a.m. and 12 p.m. to minimize time-dependent variations of skin biophysical characteristics.

Spirometry

Spirometry assessment was performed using Lungtest 1000 spirometer (MES, Krakow, Poland) according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines.Citation16 Postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC% were evaluated and recorded.

The CAT

CAT is a simple, validated health status instrument for patients with COPD. The self-administered questionnaire consists of eight items assessing various manifestations of COPD and global impact of the disease on health status. It is a simple quantified measure of health-related quality of life. Range of CAT scores is from 0 to 40. A decrease in CAT score represents an improvement in health status, whereas an increase in CAT score represents a worsening in health status.Citation17

The mMRC dyspnea scale

mMRC is a five-level rating scale based on the patient’s perception of dyspnea in daily activities. It consists of five statements that describe the entire range of dyspnea from none (Grade 0) to almost complete incapacity (Grade 4).Citation18

The 6MWT

The 6MWT is used for the evaluation of functional exercise capacity in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. In this study, 6MWT was performed using the methodology specified by the Polish Respiratory Society guidelines.Citation19 Briefly, all COPD patients were instructed to walk as far as possible during 6 minutes. The 6MWT was performed in a flat, long, covered corridor which was 30 m long, meter-by-meter marked. When the test was finished, the distance covered by each was calculated.

BODE index

This multidimensional scoring system for COPD patients evaluates body mass index (BMI), measure of airflow obstruction (FEV1% predicted), dyspnea score (grade in mMRC scale), and exercise capacity (distance covered in 6MWT). This composite marker of disease takes into consideration the systemic nature of COPD and is used to predict long-term outcomes in this population.Citation20

Biomarkers of systemic inflammation

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) were measured in serum using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA, R&D Systems, Inc., Min-neapolis, MN, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated. Normality of data distribution was tested with Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a post hoc Tukey test. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed with Kruskal–Wallis test with the post hoc Dunn’s test. Correlations were analyzed with Pearson correlation coefficient. Significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Summary of characteristics of study participants is shown in . COPD patients were older than the control group and had greater mean smoking exposure than healthy smokers group. The mean time since diagnosis of COPD was 7.05±1.00 years and mean FEV1 was 61.98%±2.76% of predicted value. COPD patients were symptomatic with a mean CAT score of 15.8±1.18 points.

Table 1 Characteristics of study participants

Biophysical skin properties

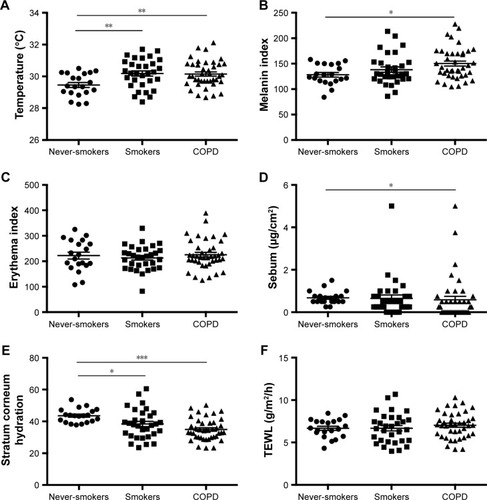

The mean and standard error of mean (SEM) of measured biophysical skin parameters in all participants are shown in . Skin temperature was significantly lower in healthy never-smokers (29.46°C±0.16°C) compared with healthy smokers (30.18°C±0.16°C; P<0.01) and COPD subjects (30.15°C±0.13°C; P<0.01). Stratum corneum hydration was higher in never-smokers (43.60±0.97) compared with smokers (38.35±1.66; P<0.05) and COPD subjects (34.91±1.08; P<0.001). Mean skin melanin level was elevated in COPD subjects (150.2±4.95) compared with never-smokers (128.2±4.47; P<0.05). Mean sebum level was lower in COPD (0.58±0.16) compared with never-smokers (0.67±0.06; P<0.05). Erythema index and TEWL did not differ significantly between studied groups.

Figure 1 Biophysical skin parameters in never-smokers, smokers, and COPD subjects.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TEWL, transepidermal water loss.

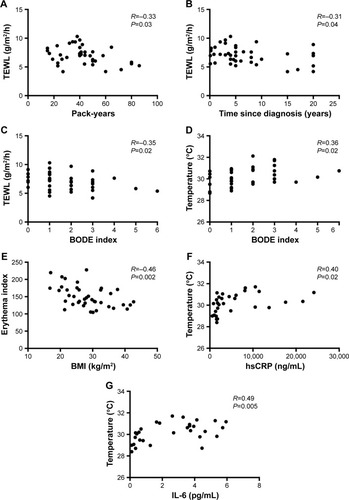

Correlations of biophysical skin variables with clinical measures

We found that in COPD subjects TEWL correlated negatively with the number of pack-years (R=−0.33; P=0.03), time since diagnosis (R=−0.31; P=0.04), and BODE index (R=−0.35; P=0.02). Skin temperature correlated positively with BODE index (R=0.36; P=0.02) while erythema index correlated negatively with BMI (R=−0.46; P=0.002) in COPD group as shown in . None of the biophysical skin variables measured correlated with age in any of the groups studied (data not shown). The most relevant and significant correlations between biophysical skin variables and clinical measures in COPD subjects are shown in .

Table 2 Correlations of biophysical skin variables with clinical measures in COPD subjects

Figure 2 Graphical representation of the most relevant and significant correlations between biophysical skin variables and clinical measures in COPD subjects (A–E), and biomarkers of systemic inflammation in smokers (F and G).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BODE, BMI, airway obstruction, dyspnea, exercise capacity; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; TEWL, transepidermal water loss.

Biomarkers of systemic inflammation

Serum hsCRP and IL-6 levels were significantly lower in never-smokers (2,046±328.8 ng/mL and 0.85±0.2 pg/mL, respectively) compared with smokers (5,907±1,155 ng/mL, P<0.05 and 2.54±0.35 pg/mL, P<0.01, respectively) as well as COPD subjects (14,715±4,780 ng/mL, P<0.001 and 6.08±1.37 pg/mL, P<0.001, respectively). There were no differences in TNF-α levels between studied groups.

Correlations of biophysical skin variables with biomarkers of systemic inflammation

We found significant correlations between skin temperature and serum hsCRP (R=0.40; P=0.02) as well as skin temperature and serum IL-6 (R=0.49; P=0.005) in smokers. Stratum corneum hydration correlated significantly with serum TNF-α (R=0.37; P=0.01) in COPD subjects. There were also significant negative correlations between erythema and serum IL-6 (R=-0.36; P=0.04) in smokers as well as erythema and serum TNF-α (R=−0.27; P=0.08) in COPD subjects. All correlations of biophysical skin variables with biomarkers of systemic inflammation are shown in . The graphical presentation of the most relevant and significant correlations between biophysical skin variables and biomarkers of systemic inflammation in smokers is shown in .

Table 3 Correlations of biophysical skin variables with biomarkers of systemic inflammation

Discussion

The complex structure of human skin and its biophysical characteristics turn it into an effective first-line defense against exogenous factors and help maintain homeostasis. This role is played by the epidermal barrier in which the corneal layer of epidermis has a particularly important function to perform. The condition of the epidermal barrier depends on its properties such as the amount of sebum produced, epidermis hydration, TEWL, or skin surface pH.Citation21

To our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate that skin biophysical properties deteriorate in COPD compared with healthy subjects and this phenomenon is caused by systemic inflammation triggered by cigarette smoke.

Skin temperature

Skin temperature is an important physiological measure that can reflect the presence of illness or injury and provide insight into the localized interactions between the body and the external environment. The human body retains tight thermoregulatory control about a set temperature of ~37°C, with life-threatening complications arising with core temperature increases as small as 3°C.Citation22 It is well known that exogenous pyrogens stimulate response of cytokine cascade in circulation, which are endogenous mediators of fever.Citation23 Among all cytokines that are measurable in blood during lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced fever, circulating levels of IL-6 show the best correlation with the febrile changes of body temperature.Citation24,Citation25 In our study, skin temperature was significantly higher in smokers and COPD patients when compared with never-smokers (), and it was accompanied by increased hsCRP and IL-6 serum concentrations. However, these markers of systemic inflammation correlated positively with skin temperature in smokers only which may suggest that systemic inflammatory response affects skin condition even in the absence of lung injury. Nevertheless, BODE index, a composite marker of severity of COPD, also correlated with skin temperature indicating that skin condition deteriorates in COPD patients as the disease progresses.Citation20

Melanin index

Melanin is one of the pigments that determine the skin color.Citation26 In our study, skin melanin index was significantly higher in the COPD cohort when compared with never-smokers group. The most important factor influencing skin pigmentation is sun exposure.Citation27 There was no observed correlation between melanin index and age of study participants, which is in agreement with previous studies.Citation28 However, it cannot be ruled out that measurements of melanin index in study participants in different seasons are responsible for observed skin pigmentation variations.

Erythema index

Quantification of erythema and pigmentation is useful for the analysis of skin tests and management of skin diseases.Citation15 Erythema is the most common presenting sign in patients with skin diseases. We found no significant differences in erythema index between the groups; however, erythema index correlated negatively with BMI in COPD subjects. Low BMI in COPD is associated with increased mortality and reduced health status, quality of life, and exercise capacity, independently of airflow limitation.Citation29–Citation31 Thus, increased skin erythema may reflect worse overall condition of COPD patients.

Sebum

Sebum forms a type of insulation against excessive humidity and variations of ambient temperature.Citation32 In our study, skin sebum level was significantly higher in COPD subjects in comparison with never-smokers. We did not observe any correlation between sebum level and age in any of the study groups, which is in agreement with findings of previous studies examining the relationship between skin sebum and age.Citation33,Citation34 In contrast, in a report from Switzerland, skin sebum level has been shown to decrease with age.Citation35 Recent data suggest that inflammatory mediators may play a more important role than previously realized in the pathogenesis of skin diseases characterized by excessive production of sebum, for instance, acne vulgaris.Citation36 It is possible that increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines generated in COPD and other chronic inflammatory conditions may trigger sebaceous glands to produce excess sebum. Increased sebum production may also be induced by nicotine, which stimulates sebocyte proliferation and lipid production.Citation37

Stratum corneum hydration

The integrity of the epidermal barrier protects the skin against the excessive loss of water and maintains the correct hydration of epidermis. We found that stratum corneum hydration was significantly reduced in smokers and COPD subjects in comparison with never-smokers. Similar to other skin variables measured in our study, we did not find a correlation between skin hydration and age in any of the studied populations. This is in line with findings of other investigations.Citation28,Citation33,Citation35 However, another study report did find a significant relationship between skin hydration and age.Citation34 Although there is a substantial body of evidence describing skin inflammation and processes that lead to its clinical manifestations, there are no data on immunologic activity that occurs in the absence of any visual inflammatory cues. It is feasible that inflammation itself may be able to induce a functional skin barrier dysfunction.Citation38 Therefore, low-grade systemic inflammation and oxidative stress generated in smokers and of greater degree in COPD subjects may impair epidermal permeability barrier function resulting in lower levels of skin hydration. This is in contrast to recent findings in a population of Chinese smokers which demonstrated significantly higher stratum corneum hydration on the forehead in light smokers (<20 cigarettes a day) than in nonsmokers. Authors of this research attribute a high skin hydration on sebaceous gland-enriched sites (eg, forehead) of smokers to increased sebum production induced by nicotine.Citation39 In the same study, authors showed lower stratum corneum hydration on sebum-impoverished site (dorsal hand) of heavy smokers (≥20 cigarettes a day). Variations of measurements of skin hydration in our study and the study performed in Chinese population may also be due to the site of assessment and ethnicity. All measurements in our study were done at the volar forearm, while authors of discussed study collected data on the dorsal hand, forehead, and cheek. Previous studies showed variations in several biophysical properties of the skin among different skin locations.Citation34 However, considering forearm as a sebum-impoverished site, our findings seem to be concordant with those from Chinese population study.Citation39

TEWL

Water loss through epidermis is described by TEWL value and affects the level of epidermis moisture.Citation12 TEWL is a parameter reflecting the integrity of epidermis water layer and is a very sensitive indicator of the epidermis barrier damage.Citation7 In our study, TEWL was not different among studied groups of subjects and age did not show any significant effect on TEWL. A negative correlation between age and TEWL has been reported in several studies.Citation33,Citation40,Citation41 However, other studies found no correlation between these two parameters.Citation34,Citation42 No difference in TEWL between never-smokers, smokers, and COPD subjects noted in our study is concordant with findings from a recent study performed in heavy cigarette smokers in a Chinese population.Citation39 While there were no differences in basal TEWL between smokers and nonsmokers, permeability barrier recovery (after barrier disruption) was delayed in heavy smokers in comparison to nonsmokers. Permeability barrier recovery rates correlated negatively with the extent of cigarettes consumption. These results indicate that while basal permeability barrier function remains unchanged, heavy cigarette smokers display altered epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis. The authors conclude that these findings suggest the pathogenic role of cigarette smoking in skin condition.Citation39 We found that in COPD subjects, TEWL also correlated negatively with the cigarette consumption, time since disease diagnosis, and BODE index. It is plausible that higher TEWL levels at early stages of disease are due to better epidermal hydration, which becomes reduced as the disease progresses. However, in contrast to our results, others found higher basal TEWL levels in cigarette smokers than in nonsmokers.Citation43 This discrepancy with our data could be attributed to measurements collected from a different body region. While Muizzuddin et al measured TEWL on the cheek,Citation43 our cohort and subjects from Chinese populationCitation39 had TEWL assessed on the forearm.

This study has several limitations, the most important being the difference in age between COPD patients and healthy smokers and never-smokers. Physiological aging could be responsible for changes in skin biophysical parameters. Although available data on this subject can be conflicting, we cannot exclude that the age difference could have biased the results. However, in our study none of the biophysical skin variables correlated with age. Comorbidities and systemic treatments are also important factors that could possibly influence obtained results. Another limitation is a small sample size. Despite the aforementioned limitations, the novel nature of our results fills a void in the literature. Studies including larger, age-balanced patient cohorts are warranted to determine the extent of skin abnormalities in COPD.

Conclusion

Experimental evaluation of serum inflammatory cytokines in our study suggests that smoking itself leads to the development of systemic inflammation, which in turn affects skin functions, observed in smokers and COPD patients. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of difference between COPD patients and smokers in any of the examined biophysical properties of the skin.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sonu Sahni MD, for his excellent English language corrections. The abstract version of this paper was presented at the 113th Annual Conference of American Thoracic Society as a poster presentation with interim findings and the poster’s abstract has been published.Citation44

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [homepage] Available from: http://goldcopd.orgAccessed June 21, 2017

- AgustiASobradilloPCelliBAddressing the complexity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: from phenotypes and biomarkery to scale-free networks, systems biology, and P4 medicineAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118391129113721169466

- BarnesPJCelliBRSystemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20093351165118519407051

- ManninoDMThornDSwensenAHolguinFPrevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200832496296918579551

- FosterTSFillerJDMartonJPCaloyerasJPRussellMWMenzinJAssessment of the economic burden of COPD in the US: a review and synthesis of the literatureCOPD20063421121817361502

- Miłkowska-DymanowskaJBiałasAJZalewska-JanowskaAGorskiPPiotrowskiWJUnderrecognized comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101331134126203239

- McGrathJAUittoJStructure and functions of the skinGriffithsCBarkerJBleikerTChalmersRCreamerDRook’s Textbook of Dermatology9th edOxford, UKWiley-Blackwell2016 Available from: http://www.rooksdermatology.com/

- KadunceDPBurrRGressRKannerRLyonJLZoneJJCigarette smoking: risk factor for premature facial wrinklingAnn Intern Med1991114108408442014944

- KohJSKangHChoiSWKimHOCigarette smoking associated with premature facial wrinkling; image analysis of facial skin replicasInt J Dermatol2002411212711895509

- AizenEGilharASmoking effect on skin wrinkling in the aged populationInt J Dermatol200140743143311678995

- PatelBDLooWJTaskerADSmoking related COPD and facial wrinkling: is there a common susceptibility?Thorax200661756857116774949

- ShahJHZhaiHMaibachHIComparative evaporimetry in manSkin Res Technol200511320520815998333

- GerhardtLCSträssleVLenzASpencerNDDerlerSInfluence of epidermal hydration on the friction of human skin against textilesJ R Soc Interface20085281317132818331977

- PandeSYMisriRSebumeterIndian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol200571644444616394496

- YamamotoTTakiwakiHAraseSOhshimaHDerivation and clinical application of special imaging by means of digital cameras and Image J freeware for quantification of erythema and pigmentationSkin Res Technol2008141263418211599

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVATS/ERS Task Force: standardisation of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD assessment testEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- MahlerDAWellsCKEvaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspneaChest19889335805863342669

- PrzybyłowskiTTomalakWSiergiejkoZPolish respiratory society guidelines for the methodology and interpretation of the 6 minute walk test (6MWT)Pneumonol Alergol Pol201583428329726166790

- CoteCGCelliBRBODE index: a new tool to stage and monitor progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePneumonol Alergol Pol200977330531319591105

- BoerMDuchnikEMaleszkaRMarchlewiczMStructural and biophysical characteristics of human skin in maintaining proper epidermal barrier functionPostępy Dermatol Alergol20163311526985171

- KennyGPJayOThermometry, calorimetry, and mean body temperature during heat stressCompr Physiol2013341689171924265242

- RothJDe SouzaGEFever induction pathways: evidence from responses to systemic or local cytokine formationBraz J Med Biol Res200134330131411262580

- RothJConnCAKlugerMJZeisbergerEKinetics of systemic and intrahypothalamic IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor during endotoxin fever in the guinea pigAm J Physiol19932653 Pt 2R653R6588214161

- LeMayLGVanderAJKlugerMJRole of interleukin-6 in fever in the ratAm J Physiol19902583 Pt 2R798R8032316725

- StamatasGNZmudzkaBZKolliasNBeerJZNon-invasive measurements of skin pigmentation in situPigment Cell Res200417661862615541019

- HillebrandGGMiyamotoKSchnellBIchihashiMShinkuraRAkibaSQuantitative evaluation of skin condition in an epidemiological survey of females living in northern versus southern JapanJ Dermatol Sci200127Suppl 1S42S5211514124

- MayesAEMurrayPGGunnDAAgeing appearance in China: biophysical profile of facial skin and its relationship to perceived ageJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol201024334134819758262

- LandboCPrescottELangePVestboJAlmdalTPPrognostic value of nutritional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med199916061856186110588597

- MostertRGorisAWeling-ScheepersCWoutersEFScholsAMTissue depletion and health related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med200094985986711001077

- HallinRJansonCArnardottirRHRelation between physical capacity, nutritional status and systemic inflammation in COPDClin Respir J20115313614221679348

- ZouboulisCCAcne and sebaceous gland functionClin Dermatol200422536036615556719

- WilhelmKPCuaABMaibachHISkin aging. Effect on transepidermal water loss, stratum corneum hydration, skin surface pH, and casual sebum contentArch Dermatol199112712180618091845280

- FiroozASadrBBabakoohiSVariation of biophysical parameters of the skin with age, gender, and body regionScientificWorldJournal2012201238693622536139

- WendlingPADell’AcquaGSkin biophysical properties of a population living in Valais, SwitzerlandSkin Res Technol20039433133814641883

- HarveyAHuynhTTInflammation and acne: putting the pieces togetherJ Drugs Dermatol201413445946324719066

- ZouboulisCCBaronJMBöhmMFrontiers in sebaceous gland biology and pathologyExp Dermatol200817654255118474083

- VestergaardCHvidMJohansenCKempKDeleuranBDeleuranMInflammation-induced alterations in the skin barrier function: implications in atopic dermatitisChem Immunol Allergy201296778022433374

- XinSYeLManGLvCEliasPMManMQHeavy cigarette smokers in a Chinese population display a compromised permeability barrierBiomed Res Int20162016970459827437403

- KobayashiHTagamiHFunctional properties of the surface of the vermilion border of the lips are distinct from those of the facial skinBr J Dermatol2004150356356715030342

- LopezSLe FurIMorizotFHeuvinGGuinotCTschachlerETransepidermal water loss, temperature and sebum levels on women’s facial skin follow characteristic patternsSkin Res Technol200061313611428940

- MarrakchiSMaibachHIBiophysical parameters of skin: map of human face, regional, and age-related differencesContact Dermatitis2007571283417577354

- MuizzuddinNMarenusKVallonPMaesDEffects of cigarette smoke on skinJ Cosmet Sci1997485235242

- MajewskiSPietrzakATworekDIs Skin Affected by Systemic Inflammation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease?Am J Respir Crit Care Med2017195A1344 Available from: http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2017.195.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1344