Abstract

Background

This study aimed to assess the adherence rate of pharmacological treatment to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guideline published in 2011 and the prevalence of comorbidities among patients with COPD in Hong Kong (HK).

Methods

Patients were recruited from five tertiary respiratory centers and followed up for 12 months. Data on baseline physiological, spirometric parameters, use of COPD medications and coexisting comorbidities were collected. The relationship between guideline adherence rate and subsequent COPD exacerbations was assessed.

Results

Altogether, 450 patients were recruited. The mean age was 73.7±8.5 years, and 92.2% of them were males. Approximately 95% of them were ever-smokers, and the mean post-bronchodilator (BD) forced expiratory volume in 1 second was 50.8%±21.7% predicted. The mean COPD Assessment Test and modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale were 13.2±8.1 and 2.1±1.0, respectively. In all, five (1.1%), 164 (36.4%), eight (1.8%) and 273 (60.7%) patients belonged to COPD groups A, B, C and D, respectively. The guideline adherence rate for pharmacological treatment ranged from 47.7% to 58.1% in the three clinic visits over 12 months, with overprescription of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and underutilization of long-acting BDs in group B COPD patients. Guideline nonadherence was not associated with increased risk of exacerbation after adjustment of confounding variables. However, this study was not powered to assess a difference in exacerbations. In all, 80.9% of patients had at least one comorbidity.

Conclusion

A suboptimal adherence to GOLD guideline 2011, with overprescription of ICS, was identified. The commonly found comorbidities also aligned with the trend observed in other observational cohorts.

Keywords:

Background

COPD is one of the leading health burdens worldwide and has been estimated to become the third leading cause of death by 2030.Citation1 In Hong Kong (HK), 10.7% of the populations are chronic smokers.Citation2 Based on the Epidemiology and Impact of COPD (EPIC) Asia survey by Lim et al,Citation3 the estimated prevalence of stable COPD was 7.7%, and 16.1% in these COPD patients met the definition of severe symptomatic phenotype. In the same study, a significant proportion of these COPD patients also reported “very poor” to “fair” general health status and unplanned health care utilization.Citation3 In 2005, COPD was the third leading cause of respiratory mortality and ranked second as a respiratory cause of hospitalization and inpatient bed-days in HK.Citation4 In the US, the hospitalizations and readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) are prevalent and costly.Citation5,Citation6

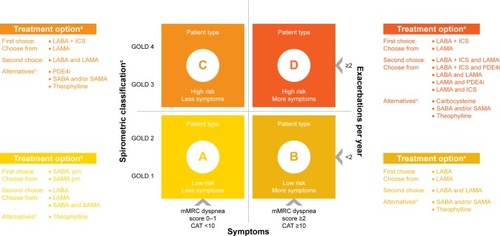

To meet the rising cost and quality of COPD care, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guideline was first released in 2001. Since its publication, it quickly became an important reference for COPD treatment. There was a major revision of the GOLD guideline in 2011, with incorporation of functional level and risk of future exacerbation,Citation7 based on the fact that COPD is a disease with multifaceted nature and the management plan should not rely on airflow limitation alone. According to the spirometric parameters, history of recent exacerbation, functional status in terms of modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) score or COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, COPD patients are categorized into groups A to D accordingly (). Within each group of patients, a set of medications are recommended for disease control and prevention of exacerbation. Bronchodilators (BDs), especially long-acting agents, are considered as the backbone of pharmacological treatment, either as first-line or alternative choices.

Figure 1 COPD grouping and pharmacological management recommended by GOLD guideline 2011.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; PDE4i, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors; prn, as needed (pro renata); SABA, short-acting β2-agonist; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist.

The attending physicians may not always adhere to the guideline, as seen in other common medical conditions.Citation8 Despite the availability of the GOLD guideline and its recommendation of stage-based pharmacotherapy, many studies showed inadequate adherence.Citation9–Citation12 Reasons including poor familiarity with the GOLD guideline and difficulty in assessing response to therapy may contribute to suboptimal guideline adherence.Citation12,Citation13 It was reported that guideline-oriented pharmacotherapy might improve airflow limitation and lower health care cost.Citation14,Citation15

In addition, COPD is associated with various respiratory and non-respiratory comorbidities, which impose negative impacts on patients, leading to impaired functional status and a higher mortality rate.Citation16 Scattered reports on the prevalence of COPD comorbidities in HK have been published, but data from large-scale studies are lacking.Citation17,Citation18

The primary objective of the current study was to evaluate the adherence rate of pharmacological treatment to the GOLD guideline published in 2011 in HK. The secondary objective was to investigate the prevalence of comorbidities among COPD patients in the local public hospitals.

Methods

Study design and patient recruitment

This 12-month, multicenter observational study was conducted in five public hospitals with tertiary referral clinics in HK between March 2013 and February 2015. Consecutive patients were recruited from outpatient clinics of these hospitals if a diagnosis of COPD was made according to the GOLD guideline and results of spirometry testing were either available within 6 months prior to study enrollment or could be performed at the baseline visit. Concurrent participation in another clinical trial was the only exclusion criterion. Informed consents were obtained from the patients or provided by a legally acceptable representative of the patient if they were incapable of doing so. The study was approved by the corresponding ethics committees of the participating hospitals (The Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong – New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Research Ethics Committee [Kowloon Central/Kowloon East] and Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee).

The observational period of 12 months covered three clinic visits every 6 months for each patient. In the baseline visit (visit 1), patients were treated according to the attending physicians’ decision and baseline clinical data were collected. The second (visit 2) and final (visit 3) visits were conducted at months 6 and 12, respectively. As this study was designed to reflect the real-life setting of clinical practice, the assignment of the patient to the therapy would be decided by the attending physicians and not predefined by the study protocol. In order to evaluate the adherence to the GOLD guideline 2011, COPD treatment, concomitant medications, adjustment of medication, reasons of treatment change and use of rescue medications were recorded. Throughout the study period, the occurrence of exacerbations and death were recorded. Spirometric measurements were performed according to the criteria recommended by the American Thoracic Society and referenced according to the Global Lung Function Initiative spirometric prediction equations.Citation19,Citation20

Sample size calculation

An earlier study estimated that 139,000 moderate or severe COPD cases in people aged ≥30 years occurred in HK using a COPD prevalent model, which implied a 3.5% prevalence rate.Citation21 The sample size calculation was based on precision approach. We planned a random sample to seek a 95% confidence interval (CI) that the sample was representative of the COPD population in HK. As this was a measure of adherence of a new guideline, the rate of adherence was uncertain and conservatively assumed to be 50%. Assuming a 95% CI, margin of error of 5% and variability of a rate of 50%, the estimated sample size would be 385. Considering an attrition rate of 10% during the study, a total of 428 subjects were required.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics including demographic data, spirometric parameters and history of exacerbations of patients were summarized by descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were represented by mean and median, and categorical data were represented by values in percentage. The status of guideline adherence was stratified into adherent, overtreated and undertreated groups. The combinations of pharmacological treatment of each group are listed in . The number of COPD exacerbation episodes throughout the 12 months was collected for those patients with the same status of guideline compliance across visits 1 and 2. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the number of exacerbations between adherent, overtreated and undertreated groups. Linear regression analysis with adjustment of confounding variables was performed if any significant association was found between treatment adherence status and exacerbation rate over 12 months. For the incidence of different comorbidities among individual COPD groups, they were compared using the chi-square test. All tests were two tailed, and significance was set at 0.05. Data analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics software version 22.0.

Table 1 Definition of overtreatment and undertreatment for different groups of COPD patients

Results

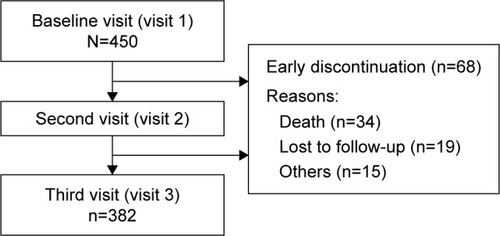

A total of 450 patients were recruited from the respiratory clinics of five hospitals. After 12 months of observation, 68 (15.1%) patients dropped out from the study. Approximately half (34, 54.0%) of the patients died, and approximately one-third (19, 30.2%) of them were lost to follow-up ().

Patient characteristics

Baseline demographics are shown in . The mean number of AECOPD before enrollment was 1.6±1.9 episodes, and ~60% of patients belonged to GOLD group D according to the guideline classification.

Table 2 Baseline sociodemographics and clinical characteristics

Treatment characteristics

The frequency of COPD medication use is shown in . Short-acting β2-agonist (SABA) was the most commonly prescribed inhaler with >85% of groups B, C and D patients having received it throughout the study period. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) alone were not commonly used in groups A and B patients. However, ICS was used in combination, especially with long-acting β2-agonist (LABA), contributing to a high rate of prescription in all COPD stages. Except for patients in groups A and C, the use of ICS in COPD patients could be up to >80%. Among different BDs, the use of any LABA outweighed the use of any long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) most of the time. More than 50% of patients received LABA at each visit, with an increasing trend observed. The rate of LABA use approached 90% among group D patients. Such a high rate of LABA prescription was mainly due to the use of LABA/ICS combination. Theophylline was quite commonly used, but roflumilast was rarely used in the 12-month period.

Table 3 Use of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments by COPD grouping at different visits (by class of treatment)

Physicians could adjust the treatment at each clinical visit according to the medical need (). Among those who had changed treatment, the most common reason was insufficient disease control.

Table 4 Reasons for change of pharmacological therapy

Primary objective

Guideline adherence on pharmacological treatment

There was a decreasing trend for the adherence rate throughout this 12-month study, with 58.2% at baseline, 47.7% at month 6 and 51.6% at month 12 (). The guideline adherence was mainly observed in group D patients, with >95% of treatment compliance falling within this group of patients.

Table 5 Adherence rate to GOLD guideline 2011

Although both undertreatment and overtreatment contributed to guideline nonadherence, the overtreatment group shared a greater proportion. More patients were undertreated in group B than those in group D (p<0.001), and group B patients contributed to >90% of the proportion in the over-treatment group at all three visits. A significant proportion of overtreatment was due to the use of ICS, either alone or together with LABA, in patients of groups A and B.

Association between guideline adherence and AECOPD

Adherent group patients had significantly more episodes of AECOPD when compared with the overtreated group (p<0.001) and undertreated group (p<0.001). The figures are shown in . Analysis was performed and confirmed significant associations between COPD GOLD grouping, frequency of AECOPD 1 year prior to study enrollment, treatment adherence and subsequent episodes of AECOPD. After adjustment for COPD GOLD grouping and frequency of AECOPD 1 year prior to study enrollment, patients who were treated according to guideline had more episodes of AECOPD than those who were undertreated (p<0.001). However, there was no association between overtreatment and exacerbation rate over 1 year (p=0.593).

Table 6 Adherence rate to GOLD guideline 2011 and exacerbation rate

Secondary objectives

In all, 364 (80.9%) patients had coexisting comorbidities at the baseline visit (), and hypertension (HT) was the most common single disease (40.7%). Patients who were in groups B and D at baseline had higher prevalence of comorbidities (74.4% and 85.3%, respectively) than those in COPD groups A and C at baseline (60.0% and 75.0%, respectively; p=0.035). Group D patients had more coexisting heart failure than group B patients.

Table 7 Summary of comorbidities by baseline COPD groupings

Discussion

This 12-month observational study reflects the local prescription pattern of pharmacological treatment in the hospital respiratory clinic setting. The baseline patient characteristics were comparable with other local and international COPD studies, which comprised mainly male heavy smokers, with similar body mass index (BMI) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) levels.Citation18,Citation22–Citation24 The spectrum of COPD included patients of groups A–D, with a distribution skewed toward the categories with more symptoms (groups B and D) with relatively high mMRC and CAT scores. This finding is different from the data obtained in the EPIC Asia population-based study, which was mainly a cross-sectional population-based survey.Citation3 Instead, this type of patient distribution has been observed in the FLAME trial.Citation25

To date, this has been the only large-scale observational study in HK investigating the treatment adherence to GOLD guideline 2011 on COPD patients. The adherence rate shown in this study was suboptimal, although there was no standard threshold of satisfactory adherence. The adherence rate to the GOLD guideline 2011 varied from 18.0% to 70.1% for various overseas studies.Citation22,Citation26–Citation28 The main reason for guideline nonadherence in the current study was due to overtreatment, especially the overuse of ICS in low-risk patients alone or in combination with other BDs, which had also been reported in a Turkish study.Citation22 Long-acting BDs were indicated for group B patients, but they were underutilized. More than 65% of group B patients received LABA/ICS combination, but only a minor proportion of them received single or combined long-acting BDs. The widespread use of LABA/ICS combination may be explained by its longer marketing history and better availability in the public health care system, contributing to a much higher utilization rate than LAMA or LABA monotherapy. Concerns of ICS overuse have been studied frequently in the last few years, especially for its inferior efficacy of bronchodilation and higher risk of causing pneumonia.Citation29,Citation30

The pattern of oral pharmacological treatment in the current study is different from other studies. Quite a number of patients received oral theophylline during the study period. When comparing with other inhaled BDs, theophylline was much cheaper and its prescription was not restricted by the public health care system. Despite having more systemic side effects, it was an attractive choice of treatment across all four groups of local COPD patients. The use of roflumilast in patients of groups A and B is obviously out of the guideline recommendations, which suggested use of roflumilast in patients of groups C and D. Although this practice was uncommon in the current study, it might reflect inadequate understanding of its indications.

The adherence rate to the GOLD guideline was shown to be variable by several studies.Citation9–Citation11 Nonadherence rates were reported in these studies, but only a few of them subdivided the types of nonadherence into categories of under- or overtreatment.Citation26,Citation28 The underlying reasons for guideline non-adherence were not evaluated in this study. We postulated that this would be due to inadequate symptom evaluation and suboptimal understanding of guideline recommendations.

The lack of adherence to clinical guidelines had been published before, and some of the barriers were due to the guideline itself.Citation31 With regular updates based on the latest evidence, some of these problems can be solved or minimized. However, many obstacles for GOLD guideline adherence were reported, including inadequate familiarity of guideline, lack of perceived treatment benefit, low self-efficacy and time constraints.Citation12,Citation32 Multiple strategies have been advocated in different countries to enhance the guideline adherence and physician awareness, leading to various degrees of success.Citation9,Citation12,Citation33 Unfortunately, such data are lacking in HK, and further study in this area is highly warranted.

The majority of the patients within the adherent group belonged to group D, with a higher intrinsic risk of recurrent exacerbations. After the adjustment of other confounding variables, including COPD groupings and history of AECOPD 1 year before study enrollment, the guideline adherence status was not associated with subsequent risk of AECOPD.

Various comorbidities are commonly associated with COPD. As recommended in the GOLD guideline, management of COPD patients must include identification and treatment of these comorbidities.Citation7 The concern of COPD-related comorbidities has been rising in recent years due to their significant negative impact on patient outcome. A “solar system” like COPD comorbidome was introduced by the BODE collaborative group recently, incorporating the prevalence and strength of the association between the disease and risk of death.Citation16 The interrelationship between clinical characteristics and comorbidities was also quantified by the same study group in a lung-shaped layout network.Citation34

In the current study, we evaluated commonly found comorbidities in our locality. In all, 80.9% of our patients had coexisting comorbidities, which exceeded those reported in the EPIC and EPOCA studies (39% and 42%, respectively),Citation3,Citation18 probably due to different patient populations and methodologies. HT, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease and old tuberculosis are the common comorbidities in the current and various local and overseas studies.Citation16,Citation17,Citation34 Three aspects of barriers for comorbidity detection have been described by Maurer et al,Citation35 including patient-perceived, physician-perceived and system-level barriers.Citation36,Citation37 As cumulating evidence is now available for the management of these comorbidities,Citation38 a well-structured screening protocol or program-based multimodality COPD care service should be developed. Obesity and advanced age were found to be associated with the presence of comorbidities, as they are believed to be common risk factors shared by COPD and certain comorbidities.Citation39

There were several limitations in our study. First, as an observational study with a self-reporting mechanism, treatment details including reasons for nonadherence and medication change might not be always available due to recall bias. Second, the COPD groupings could be different if the attending physician chose to use one instead of another factor, for example, to use mMRC score instead of CAT score. This difference could affect the choice of pharmacological treatment significantly.Citation40,Citation41 Third, the sample size was not large enough to predict the effect of treatment nonadherence on mortality, COPD exacerbation and pneumonia due to ICS overuse. Fourth, as our study did not require a thorough screening of comorbidities and no management modification was made to the clinical follow up, there might be a possibility of underreporting of comorbidities. Finally, the study population skewed toward groups B and D due to high mMRC or CAT scores, which signified that the patients were highly selective and this might not completely reflect the usual pattern of disease burden.Citation3 This distribution of disease grouping may therefore limit the generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

In summary, the current study involving subjects with typical COPD clinical characteristics demonstrated a suboptimal adherence to GOLD guideline 2011 and overtreatment, especially overprescription of ICS. The most commonly found COPD-related comorbidities also aligned with the trend observed in local and nation-wide observational cohorts.

Acknowledgments

The five hospitals received an unrestricted financial grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals (HK) Ltd.

Disclosure

All authors reported no conflicts of interest in this work and received no personal fee from any grant or commercial companies.

References

- World Health OrganizationWorld Health StatisticsGenevaWorld Health Organization2008

- Tobacco Control Office, Department of HealthSmoking Cessation InformationHong KongTobacco Control Office, Department of Health2015

- LimSLamDCMuttalifARImpact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the Asia-Pacific region: the EPIC Asia population-based surveyAsia Pac Fam Med2015141425937817

- Chan-YeungMLaiCKChanKSHong Kong Thoracic SocietyThe burden of lung disease in Hong Kong: a report from the Hong Kong Thoracic SocietyRespirology200813suppl 4S133S16518945323

- JencksSFWilliamsMVColemanEARehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service programN Engl J Med2009360141418142819339721

- ShahTChurpekMMCoca PerraillonMKonetzkaRTUnderstanding why patients with COPD get readmitted: a large national study to delineate the Medicare population for the readmissions penalty expansionChest201514751219122625539483

- global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD). CommitteeGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease2011 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/Guidelines/guidelines-resources.htmlAccessed August 13, 2013

- EdepMEShahNBTateoIMMassieBMDifferences between primary care physicians and cardiologists in management of congestive heart failure: relation to practice guidelinesJ Am Coll Cardiol19973025185269247527

- SharifRCuevasCRWangYAroraMSharmaGGuideline adherence in management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med201310771046105223639271

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated health-care resource use – North Carolina, 2007 and 2009MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep201261814314622377845

- PriceDWestDBrusselleGManagement of COPD in the UK primary-care setting: an analysis of real-life prescribing patternsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014988990425210450

- PerezXWisniveskyJPLurslurchachaiLKleinmanLCKronishIMBarriers to adherence to COPD guidelines among primary care providersRespir Med2012106337438122000501

- SalinasGDWilliamsonJCKalhanRBarriers to adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease guidelines by primary care physiciansInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011617117921468169

- ChiangCHLiuSLChuangCHJhengYHEffects of guideline-oriented pharmacotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed COPD: a prospective studyWien Klin Wochenschr201312513–1435336123817861

- AscheCVLeaderSPlauschinatCAdherence to current guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among patients treated with combination of long-acting bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroidsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012720120922500120

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPBODE Collaborative GroupComorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186215516122561964

- AuLHChanHSSeverity of airflow limitation, co-morbidities and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients acutely admitted to hospitalHong Kong Med J201319649850323784531

- MiravitllesMMurioCTirado-CondeGGeographic differences in clinical characteristics and management of COPD: the EPOCA studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083480381419281096

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVStandardisation of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- QuanjerPHStanojevicSColeTJMulti-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equationsEur Respir J20124061324134322743675

- Regional COPD Working GroupCOPD prevalence in 12 Asia-Pacific countries and regions: projections based on the COPD prevalence estimation modelRespirology20038219219812753535

- TuranOEmreJCDenizSBaysakATuranPAMiriciAAdherence to current COPD Guidelines in TurkeyExpert Opin Pharmacother201617215315826629809

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBTORCH InvestigatorsSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSUPLIFT Study InvestigatorsA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2008359151543155418836213

- WedzichaJABanerjiDChapmanKRFLAME InvestigatorsIndacaterol–glycopyrronium versus salmeterol–fluticasone for COPDN Engl J Med2016374232222223427181606

- MaioSBaldacciSMartiniFCOMODHES Study GroupCOPD management according to old and new GOLD guidelines: an observational study with Italian general practitionersCurr Med Res Opin20143061033104224450467

- MiravitllesMSicrasACrespoCCosts of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in relation to compliance with guidelines: a study in the primary care settingTher Adv Respir Dis20137313915023653458

- PapalaMKerenidiNGourgoulianisKIEveryday clinical practice and its relationship to 2010 and 2011 GOLD guideline recommendations for the management of COPDPrim Care Respir J201322336236423989678

- SpencerSKarnerCCatesCJEvansDJInhaled corticosteroids versus long-acting beta2-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev2011712CD007033

- KewKMSeniukovichAInhaled steroids and risk of pneumonia for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD01011524615270

- CabanaMDRandCSPoweNRWhy don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvementJAMA1999282151458146510535437

- DesaluOOOnyedumCCAdeotiAOGuideline-based COPD management in a resource-limited setting – physicians’ understanding, adherence and barriers: a cross-sectional survey of internal and family medicine hospital-based physicians in NigeriaPrim Care Respir J2013221798523443222

- OveringtonJDHuangYCAbramsonMJImplementing clinical guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: barriers and solutionsJ Thorac Dis20146111586159625478199

- DivoMJCasanovaCMarinJMBODE Collaborative GroupCOPD comorbidities networkEur Respir J201546364065026160874

- MaurerJRebbapragadaVBorsonSACCP Workshop Panel on Anxiety and Depression in COPDAnxiety and depression in COPD: current understanding, unanswered questions, and research needsChest20081344 suppl43S56S

- VanfleterenLEFranssenFMUszko-LencerNHFrequency and relevance of ischemic electrocardiographic findings in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Cardiol2011108111669167422077976

- TriestFJFranssenFMSpruitMAGroenenMTWoutersEFVanfleterenLEPoor agreement between chart-based and objectively identified comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20154651492149526341984

- VanfleterenLESpruitMAWoutersEFFranssenFMManagement of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease beyond the lungsLancet Respir Med201641191192427264777

- BrownJPMartinezCHChronic obstructive pulmonary disease comorbiditiesCurr Opin Pulm Med201622211311826814720

- HuangWCWuMFChenHCHsuJYTOLD GroupFeatures of COPD patients by comparing CAT with mMRC: a retrospective, cross-sectional studyNPJ Prim Care Respir Med2015251506326538368

- ZoggSDürrSMiedingerDStevelingEHMaierSLeuppiJDDifferences in classification of COPD patients into risk groups A-D: a cross-sectional studyBMC Res Notes2014756225148698