Abstract

Background

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the predominant cause of death in patients with COPD, and the severity of COPD in NSCLC patients is classified mainly as mild to moderate. Most advanced NSCLC patients with mild to moderate COPD are treated with chemotherapy; however, the feasibility for and prognosis after chemotherapy of these patients are not well understood. The aim of this study was to elucidate the impact of mild to moderate COPD on the feasibility for and prognosis after chemotherapy in NSCLC patients.

Patients and methods

A retrospective review was performed on 268 NSCLC patients who received first-line chemotherapy from 2009 to 2014 in our institution. Finally, 85 evaluable patients were included in this study. The clinical characteristics, toxicity profile, objective response rate, and prognosis were analyzed and compared between patients with mild to moderate COPD and those without COPD (non-COPD).

Results

Forty-three patients were classified as COPD (27 cases mild and 16 cases moderate) and 42 patients as non-COPD. The COPD group were older and had fewer never-smokers than the non-COPD group. The objective response rate did not differ between groups (p=0.14). There was no significant difference in overall survival between COPD and non-COPD groups (15.0 and 17.0 months, log-rank test p=0.57). In the multivariate Cox’s proportional hazard model, the adjusted hazard ratio (HRadj) was statistically significant for male sex (HRadj =5.382, 95% CI: 1.496–19.359; p=0.010), pathological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (HRadj =0.460, 95% CI: 0.223–0.948; p=0.035), and epithelial growth factor receptor negative mutation (HRadj =6.040, 95% CI: 1.158–31.497; p=0.033), but not for the presence of COPD (HRadj =0.661, 95% CI: 0.330–1.325; p=0.24). Toxicity profile in COPD group was favorable, as in the non-COPD group.

Conclusion

Mild to moderate COPD did not have a significant deleterious impact on toxicity and prognosis in NSCLC patients.

Keywords:

Introduction

Lung cancer (LC) is currently the most common cancer worldwide. Despite years of clinical research and the development of multiple chemotherapeutic regimens, survival of patients with advanced LC remains dismal. Among LC diagnoses, the majority are of non-small cell LC (NSCLC). Several factors, such as sex, performance status (PS), epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation status, and the presence of comorbidities, are reported to be associated with prognosis in advanced NSCLC.Citation1,Citation2 The presence of comorbidities influences not only prognosis but also management, because patients with comorbidities are less likely to receive chemotherapy.Citation3

COPD is regarded as one of the important comorbidities in NSCLC patients, with a prevalence of 50%–70%.Citation4–Citation7 On the other hand, patients with COPD also have an increased risk of LC. Previous studies have reported that the main cause of death in patients with severe COPD is respiratory failure, whereas LC and cardiovascular disease are the predominant causes in patients with mild to moderate COPD.Citation8 The severity of COPD in patients with newly diagnosed LC is usually classified as mild to moderate.Citation6,Citation9 Most advanced NSCLC patients with mild to moderate COPD are treated with chemotherapy; therefore, addressing the potential impact of COPD on treatment outcomes of NSCLC patients may be crucial in optimizing the management and prognosis of NSCLC patients. However, whether mild to moderate COPD impacts the feasibility for and prognosis after chemotherapy for NSCLC patients has not been well studied because pulmonary function tests are not usually conducted in these patients.

Here, we conducted a pulmonary function test for NSCLC patients before treatment and assessed the presence and severity of COPD. The aim of this study was to elucidate the impact of mild to moderate COPD on the feasibility for and prognosis after chemotherapy in NSCLC patients.

Material and methods

Study subjects

The medical records of 268 consecutive patients with NSCLC who received first-line cytotoxic chemotherapy at Nagoya University Hospital between January 2009 and December 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. Data were collected from our institutional cancer registry database and patient follow-up visits. We excluded 183 patients for the following reasons: 1) treatment with radiochemotherapy or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as first-line chemotherapy, 2) unavailability of pulmonary function test data, and 3) severe COPD. Finally, 85 evaluable patients were included.

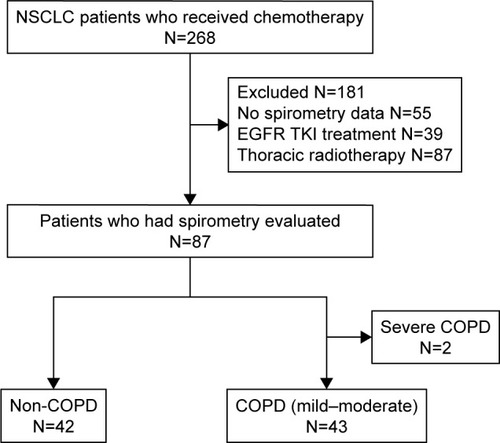

Of these 85 patients, 43 patients were diagnosed with COPD, and 42 patients did not have COPD (non-COPD; ). Twenty-seven patients were classified as having mild COPD and 16 patients as having moderate COPD, according to the spirometric criteria of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease as follows: 1) non-COPD: forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ≥70%, 2) mild COPD: FEV1/FVC <70% and FEV1 ≥80% predicted, 3) moderate COPD: FEV1/FVC <70% and 50%≤ FEV1 <80% predicted, and 4) severe COPD: FEV1/FVC <70% and 30%≤ FEV1 <50% predicted.Citation10 Based on clinical data, we excluded patients who had history or evidence of other diseases with chronic airflow obstruction such as asthma, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, and cystic fibrosis from this study.

Figure 1 Screening and inclusion process for patients in the study.

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

We evaluated the objective response rates (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), median overall survival (OS), and toxicity profiles and compared these between patients with COPD and non-COPD.

This study was approved by the Nagoya University Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB, No 2016-0222). The requirement for informed consent from the patients of this study was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature, and any personal information from the data was removed beforehand.

Data collection

The data collected for all patients included age, sex, smoking habit, pack-years index, symptoms, PS on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale, tumor–node–metastasis staging, histology, laboratory data, spirometric values, treatment, toxicity profiles, and survival.

Outcomes and toxicities

OS was measured as the period from the diagnosis of LC to death. ORR was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. Clinical benefit was defined as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease, or progressive disease (PD), and from these data, DCR (CR + PR + stable disease) and ORR (CR + PR) were determined. All toxicities were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as means ± standard deviation or median (range). The chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous data. Differences in the values for pulmonary function tests were evaluated using the paired Student’s t-test. Chi-squared statistics or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions. Survival curves were compared with the log-rank test, and Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted. Cox’s proportional hazards models were used to adjust for age, sex, tumor stage, PS, pathological diagnosis, EGFR mutation status, and the presence of COPD. All data were analyzed using a statistical software package (SPSS, version 23.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The baseline patient characteristics are shown in . The mean age of patients with COPD was higher compared to those with non-COPD, and the proportion of never-smoker was lower in patients with COPD than those with non-COPD. There were significant differences in COPD-related symptoms such as dyspnea and sputum between the COPD group and non-COPD group. There were no significant differences in sex, PS, histological subtype, tumor stage, and EGFR mutation status.

Table 1 Patient characteristics and baseline physiological data depending on the presence or absence of COPD

As for baseline physiological data, there were no significant differences in baseline laboratory data including total protein, albumin, creatinine, total bilirubin, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, and glutamic–pyruvic transaminase.

Treatment and response

As shown in , the most frequently administered regimen was carboplatin-based doublet chemotherapy (76.5%) in both COPD and non-COPD patients, and the treatment cycles did not differ between the groups (p=0.15). Nine patients were positive for EGFR mutation and received EGFR-TKI treatment after the failure of first-line chemotherapy. Six COPD patients and five non-COPD patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 2 Treatment and outcome

The ORR and DCR were 38.9% and 58.3%, respectively, in patients with COPD and 22.9% and 57.1%, respectively, in patients with non-COPD. There was no significant difference in ORR (p=0.14) or DCR (p=0.92) between COPD and non-COPD patients.

Prognosis

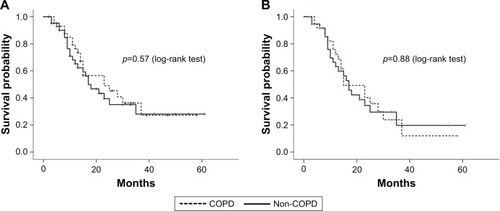

The Kaplan–Meier curves for COPD and non-COPD patients are shown in . The median OS in COPD and non-COPD patients was 15.0 and 17.0 months, respectively, and the difference did not reach significance (log-rank test, p=0.57). This result was unchanged even when we excluded patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy (p=0.88; ).

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for overall survival.

In the univariate Cox’s proportional hazard analyses for factors affecting OS, male sex (hazard ratio [HR] =3.536, 95% CI: 1.092–11.450; p=0.035), pathological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (HR =0.486, 95% CI: 0.259–0.911; p=0.024), and EGFR negative mutation (HR =5.655, 95% CI: 1.304–24.519; p=0.021) were significantly associated with survival. In the multivariate Cox’s proportional hazard model adjusting for the most relevant variables, the adjusted hazard ratio (HRadj) was statistically significant for male sex (HRadj =5.382, 95% CI: 1.496–19.359; p=0.010), pathological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (HRadj =0.460, 95% CI: 0.223–0.948; p=0.035), and EGFR negative mutation (HRadj =6.040, 95% CI: 1.158–31.4971; p=0.033), but not for the presence of COPD (HRadj =0.661, 95% CI: 0.330–1.325; p=0.24; ).

Table 3 Cox’s proportional hazards analyses for factors affecting OS

Toxicity

The most frequently recorded toxicities are shown in . In general, treatment was well tolerated, and there were no significant differences in toxicity between COPD and non-COPD patients. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in grades 3–4 severe toxicity between the patient groups. Neutropenia was the most frequent grades 3–4 toxicity in each group. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Table 4 Adverse events

Discussion

In the present study, mild to moderate COPD did not have a significant impact on feasibility and tumor response for NSCLC patients who received first-line cytotoxic chemotherapy. In addition, mild to moderate COPD was not significantly associated with survival of these patients. The presence of mild to moderate COPD might not be a concern for withholding chemotherapy in NSCLC patients.

Regarding prognosis, mild to moderate COPD was not significantly associated with survival of NSCLC patients in our study. Several prognostic factors such as age, tumor stage, pathology, and EGFR mutation status have been reported in NSCLC patients.Citation2,Citation11 In our study, there were no significant differences in these factors between COPD and non-COPD groups. Moreover, we excluded NSCLC patients treated with radiochemotherapy or EGFR-TKI therapy to minimize the impact of treatment intensity on prognosis in comparison of COPD and non-COPD patients, because there are substantial differences in the effectiveness and toxicity profiles of cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiochemotherapy or EGFR-TKI therapy.Citation11–Citation13 Consistent with our results, a previous study showed that the presence of COPD was not associated with poor prognosis of NSCLC patients who received chemotherapy or EGFR-TKI therapy.Citation11 Moreover, it remains controversial whether the presence of mild to moderate COPD is associated with prognosis of NSCLC patients who undergo lung resection.Citation6,Citation14,Citation15 These data suggested that mild to moderate COPD did not have a significant impact on prognosis in NSCLC patients. Another explanation for our results is that there were no significant differences in ORR and toxicity profile of chemotherapy between patients with COPD and non-COPD. Severe toxicity during chemotherapy for NSCLC patients tends to result in early treatment termination, which decreases the efficacy of chemotherapy.Citation16 In our study, there were no significant differences in chemotherapy cycles between COPD and non-COPD patients.

In our study, there was no significant difference in ORR between COPD and non-COPD patients. Previous studies reported that patients with smoking-related LC showed higher prevalence of squamous cell carcinoma, which has been reported to be more resistant to chemotherapy than adenocarcinoma.Citation17 The majority of patients in our study with mild to moderate COPD were pathologically diagnosed with adenocarcinoma, which might therefore have affected the effectiveness of chemotherapy. Our previous study showed that the severity of COPD in Japanese patients with newly diagnosed LC was classified mainly as mild to moderate.Citation6,Citation18 In addition, previous studies reported that adenocarcinoma was the major pathological type in NSCLC patients with mild to moderate COPD.Citation5,Citation6,Citation11 These studies support our result showing a high prevalence of adenocarcinoma in patients with mild to moderate COPD.

There are limited data concerning the impact of mild to moderate COPD on the toxicity profiles of cytotoxic chemotherapy. NSCLC patients who receive chemotherapy frequently experience adverse events such as hematological, gastrointestinal, or neurological toxicity.Citation12,Citation16 In our study, there were no significant differences in toxicity profile of chemotherapy between patients with mild to moderate COPD and non-COPD. This result may be explained by the exclusion of patients with severe COPD in this study. Compared with patients with mild to moderate COPD, these patients have a higher risk of respiratory symptoms and functional impairment, which is associated with excess toxicity during cytotoxic chemotherapy.Citation19–Citation22 Most COPD patients in our study had good PS, and, therefore, the toxicity profile of patients with COPD was as favorable as that of patients with non-COPD.

On the other hand, previous studies reported that after lung resection, NSCLC patients with mild to moderate COPD had greater risk of postoperative complications, such as respiratory complications and cardiac arrhythmias, compared with those without COPD.Citation7,Citation23 NSCLC patients who undergo lung resection are subjected to general anesthesia, reduction of lung volume, and loss of inspiratory and expiratory tones.Citation24,Citation25 There are considerable differences in the impact of these interventions on respiratory systems between patients treated with lung resection and those who receive chemotherapy, and these differences may account for the distinct feasibility of these interventions for NSCLC patients with mild to moderate COPD.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the study was retrospective, and patients (20.5%) on whom spirometry was not conducted were excluded. Second, we used the COPD definition (FEV1/FVC <0.7) for diagnosing COPD, which might tend to overdiagnose COPD especially in the elderly because the FEV1 value decreases more quickly with age than the FVC.Citation26 In this study, 44% (19/43) of patients were elderly (age ≥70), and the COPD group was significantly older than the non-COPD group. Therefore, there might be a possibility that some patients were overdiagnosed as COPD. However, the data that the COPD-related symptoms such as dyspnea and sputum were more frequently seen in the COPD group than in the non-COPD group supported the diagnostic accuracy for COPD in our cohort. Third, we excluded NSCLC patients who had received EGFR-TKI therapy as first-line chemotherapy because we aimed to investigate the impact of COPD on the effectiveness and toxicity of cytotoxic chemotherapy in this study. Compared with patients with COPD, those without COPD were reported to show a higher likelihood of EGFR mutation positivity and consequently tend to receive EGFR-TKI therapy.Citation6,Citation27 Therefore, we might have recruited more patients with COPD than without COPD, thereby leading to selection bias. Fourth, the severity of air flow limitation in our cohort was restricted to mild to moderate. Severe COPD patients tend to suffer from malnutrition and functional impairment, and therefore, they are likely to have more toxicity or less effective therapy.Citation8,Citation19,Citation20,Citation28 In this study, we could not assess the impact of severe COPD on prognosis and toxicity of chemotherapy. Further investigation is needed to clarify whether severe COPD has an impact on toxicity and prognosis of NSCLC patients.

Conclusion

In summary, mild to moderate COPD did not have a significant deleterious impact on toxicity and prognosis in patients with NSCLC. The presence of mild to moderate COPD might not be a concern for withholding cytotoxic chemotherapy as first-line therapy in NSCLC patients.

Author contributions

NO and NH contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis, review, writing, and submission of this manuscript. MM contributed to study design, review, writing, and submission of this manuscript. KS contributed to review, writing, and submission of this manuscript. SM, AA, and YN contributed to review of this manuscript. YH contributed to study design and review of this manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The abstract of this manuscript was presented as a poster presentation during the American Thoracic Society International Conference in May 2017 in San Francisco. The abstract was published in the ATS International Congress 2017 Abstracts (http://www.atsjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2017.195.1_MeetingAb-stracts.A4581).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AsmisTRDingKSeymourLAge and comorbidity as independent prognostic factors in the treatment of non small-cell lung cancer: a review of National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group trialsJ Clin Oncol2008261545918165640

- RosellRMoranTQueraltCSpanish Lung Cancer GroupScreening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancerN Engl J Med20093611095896719692684

- RamseySDHowladerNEtzioniRDDonatoBChemotherapy use, outcomes, and costs for older persons with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: evidence from surveillance, epidemiology and end results-MedicareJ Clin Oncol200422244971497815611512

- LoganathanRSStoverDEShiWVenkatramanEPrevalence of COPD in women compared to men around the time of diagnosis of primary lung cancerChest200612951305131216685023

- YoungRPHopkinsRJChristmasTBlackPNMetcalfPGambleGDCOPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking historyEur Respir J200934238038619196816

- HashimotoNMatsuzakiAOkadaYClinical impact of prevalence and severity of COPD on the decision-making process for therapeutic management of lung cancer patientsBMC Pulm Med2014141424498965

- OsukaSHashimotoNSakamotoKWakaiKYokoiKHasegawaYRisk stratification by the lower limit of normal of FEV1/FVC for postoperative outcomes in patients with COPD undergoing thoracic surgeryRespir Investig2015533117123

- SinDDAnthonisenNRSorianoJBAgustiAGMortality in COPD: role of comorbiditiesEur Respir J20062861245125717138679

- MatsuoMHashimotoNUsamiNInspiratory capacity as a preoperative assessment of patients undergoing thoracic surgeryInteract Cardiovasc Thorac Surg201214556056422307392

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-2016 Available from: http://goldcopd.org/global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd-2016/Accessed April 17, 2017

- IzquierdoJLResanoPEl HachemAGrazianiDAlmonacidCSanchezIMImpact of COPD in patients with lung cancer and advanced disease treated with chemotherapy and/or tyrosine kinase inhibitorsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201491053105825336937

- MaemondoMInoueAKobayashiKNorth-East Japan Study GroupGefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFRN Engl J Med2010362252380238820573926

- MokTSWuYLThongprasertSGefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinomaN Engl J Med20093611094795719692680

- LeeSJLeeJParkYSImpact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the mortality of patients with non-small-cell lung cancerJ Thorac Oncol20149681281724807154

- GaoYHGuanWJLiuQImpact of COPD and emphysema on survival of patients with lung cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studiesRespirology201621226927926567533

- KatoTMoriseMAndoMCan we predict the development of serious adverse events (SAEs) and early treatment termination in elderly non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy?J Cancer Res Clin Oncol201614271629164027166967

- HirschFRSpreaficoANovelloSWoodMDSimmsLPapottiMThe prognostic and predictive role of histology in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a literature reviewJ Thorac Oncol20083121468148119057275

- MatsuzakiAHashimotoNOkachiSClinical impact of the lower limit of normal of FEV1/FVC on survival in lung cancer patients undergoing thoracic surgeryRespir Investig2016543184192

- JonesPWAdamekLNadeauGBanikNComparisons of health status scores with MRC grades in COPD: implications for the GOLD 2011 classificationEur Respir J201342364765423258783

- CruzJMarquesAJácomeCGabrielRFigueiredoDGlobal functioning of COPD patients with and without functional balance impairment: an exploratory analysis based on the ICF frameworkCOPD201512220721625093384

- NederJAO’DonnellCDCoryJVentilation distribution heterogeneity at rest as a marker of exercise impairment in mild-to-advanced COPDCOPD201512324925625230258

- MörthCValachisASingle-agent versus combination chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and performance status 2: a literature-based meta-analysis of randomized studiesLung Cancer201484320921424702946

- SekineYBehniaMFujisawaTImpact of COPD on pulmonary complications and on long-term survival of patients undergoing surgery for NSCLCLung Cancer20023719510112057873

- YabuuchiHKawanamiSKamitaniTPrediction of post-operative pulmonary function after lobectomy for primary lung cancer: a comparison among counting method, effective lobar volume, and lobar collapsibility using inspiratory/expiratory CTEur J Radiol201685111956196227776646

- PelletierCLapointeLLeBlancPEffects of lung resection on pulmonary function and exercise capacityThorax19904574975022396230

- HardieJABuistASVollmerWMEllingsenIBakkePSMorkveORisk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokersEur Respir J20022051117112212449163

- LimJUYeoCDRheeCKChronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related non-small-cell lung cancer exhibits a low prevalence of EGFR and ALK driver mutationsPLoS One20151011e014230626555338

- ChatilaWMThomashowBMMinaiOACrinerGJMakeBJComorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc20085454955518453370