Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of disability in all its stages, and death in patients with moderate or severe obstruction. At present, COPD is suboptimally managed; current health is often not measured properly and hardly taken into account in management plans, and the future risk for patients with regard to health status and quality of life is not being evaluated. This review addresses the effect of COPD on the lives of patients and examines ways in which existing assessment tools meet physicians’ needs for a standardized, simple method to measure consistently the full impact of COPD on patients in routine clinical practice. Current assessment of COPD severity tends to focus on airflow limitation, but this does not capture the full impact of the disease and is not well correlated with patient perception of symptoms and health-related quality of life. Qualitative studies have demonstrated that patients usually consider COPD impact in terms of frequency and severity of symptoms, and physical and emotional wellbeing. However, patients often have difficulty expressing their disease burden and physicians generally have insufficient time to collect this information. Therefore, it is important that methods are implemented to help generate a more complete understanding of the impact of COPD. This can be achieved most efficiently using a quick, reliable, and standardized measure of disease impact, such as a short questionnaire that can be applied in daily clinical practice. Questionnaires are precision instruments that contribute sensitive and specific information, and can potentially help physicians provide optimal care for patients with COPD. Two short, easy-to-use, specific measures, ie, the COPD Assessment Test and the Clinical COPD Questionnaire, enable physicians to assess patients’ health status accurately and improve disease management. Such questionnaires provide important measurements that can assist primary care physicians to capture the impact of COPD on patients’ daily lives and wellbeing, and improve long-term COPD management.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major public health problem of high and increasing prevalence,Citation1–Citation5 and is a leading cause of disability in all its stagesCitation6,Citation7 and death in patients with moderate or severe obstruction.Citation8–Citation10 COPD imposes a profound burden on patients, including medical emergencies, hospitalizations, work absenteeism, and activity limitations. Ultimately, this has a significant physical and emotional impact on patients.Citation11

COPD, as defined by airflow limitation, is often underdiagnosedCitation12–Citation14 and undertreated,Citation15 leading to poor quality of life for patients.Citation16 Current assessments of COPD severity focus on the amount of air that patients can forcibly exhale from their lungs in the first second of a forced exhalation (FEV1), but this alone does not capture the full impact of the disease.Citation17 As a consequence, patients with COPD are often suboptimally managed.Citation18,Citation19 The future risk for patients with COPD with regard to health status and quality of life is not currently being evaluated routinely, but it is likely that this will provide a marker of both current impact and future risk in these patients.Citation20–Citation24

Improved COPD management requires a range of patient assessments, including lung function, exacerbation episodes, exercise tolerance, and impact on health status. However, patients often have difficulty expressing the burden of their disease and physicians generally do not have sufficient time to collect this information. Therefore, it is important that methods are implemented to enable clinicians to reach a more complete understanding of the impact of the disease on their patients and identify specific needs. The most efficient way to achieve this is to use a quick, reliable, and standardized measure of disease impact, such as a short questionnaire, that can be applied in daily clinical practice to provide physicians with additional useful information. Validated patient-reported outcomes, eg, measurements of health status (health-related quality of life [HRQoL]), or functional status are now recognized as being key in capturing the patient’s experience of important aspects of health in chronic disease.Citation25 Use of these measures will enable physicians to determine what is really important to the individual patient and highlight differences between patients.

In conjunction with patient-reported measures, health care systems need to be more organized and focused towards meeting the current and future needs of patients with COPD. Patients with chronic disease require both regular clinician assessments and self-management. Application of the chronic care model, which includes fundamental elements (eg, the community, health care system, and patient self-management) needed to support high-quality care for patients with chronic disease, could potentially improve COPD management.Citation26–Citation28

The management of COPD is now directed towards symptomatic benefit, in terms of improved HRQoL and exercise tolerance, and risk reduction (eg, exacerbations, hospital admissions, and death). Assessment of COPD risk can now be done in routine clinical practice using simple multidimensional prognostic scaling systems, such as the DOSE index.Citation29 The aim of this review, however, is to address the impact of COPD on patients’ lives and to discuss ways in which the new assessment tools can meet physicians’ needs for a standardized, simple method to measure consistently the full impact of COPD on patients in routine clinical practice.

Measuring impact of COPD on patients

The burden of COPD on patients and their families is high.Citation13,Citation30–Citation32 Furthermore, it is not limited to patients with severe COPD, but is also very prominent in younger patients with only mild or moderate airway obstruction, limiting them in their daily lives.Citation33 In general, patients have a restricted understanding of both the extent of their loss of pulmonary function and the severity of their COPD. In the Confronting COPD International Survey, patients’ perceptions of the severity of their COPD did not consistently correspond with the degree of severity indicated by the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea (breathlessness) scale.Citation16 In addition, most patients do not appear to place the same level of importance on their exacerbation episodes as health care providers,Citation34 and a recent study showed that patients generally report smaller changes in HRQoL outcome measures as more clinically meaningful than do physicians.Citation35 Thus, the provision of measures to document clinical outcomes can help both patients and health care providers improve their knowledge about the impact of COPD on patient health.

Surveys have indicated that patients usually consider the impact of COPD in terms of symptom frequency and severity, and physical and emotional wellbeing.Citation16 In the Confronting COPD in America survey, 90% of individuals with COPD experienced symptoms either every day or most days during their worst three-month period in the past year ().Citation36 Also, patients use language such as “good” and “bad” days to define how COPD influences their HRQoL, so patients’ self-reported assessments are important when evaluating the intensity of symptoms, such as dyspnea and fatigue, and their impact on HRQoL.Citation37

Figure 1 Symptom frequency in individuals with COPD (evaluation of worst three-month period in past year). Patients participating in the Confronting COPD in America survey were asked about the frequency of their symptoms during their worst three-month period in the past year (ie, “Has there been any three-month period in the past year when you experienced … [read item] – every day, most days a week, a few days a week, a few days a month, less than that?”). A high proportion of patients reported that they frequently experienced specific disease-associated outcomes during their worst period in the past year.Citation36

Reproduced with permission from GlaxoSmithKline.

![Figure 1 Symptom frequency in individuals with COPD (evaluation of worst three-month period in past year). Patients participating in the Confronting COPD in America survey were asked about the frequency of their symptoms during their worst three-month period in the past year (ie, “Has there been any three-month period in the past year when you experienced … [read item] – every day, most days a week, a few days a week, a few days a month, less than that?”). A high proportion of patients reported that they frequently experienced specific disease-associated outcomes during their worst period in the past year.Citation36Reproduced with permission from GlaxoSmithKline.](/cms/asset/e9fa0258-1960-4b6b-bf8e-a773501d8726/dcop_a_18181_f0001_c.jpg)

Changing health status

A study in patients with stable COPD showed that changes in health status assessed by patient-reported measures (eg, the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ], Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire [CRQ], MRC dyspnea scale, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]) worsened significantly over time.Citation38 However, deteriorations in patient-reported outcomes (eg, symptoms, limitation of daily activities, and wellbeing) showed only a weak correlation with changes in physiological indices such as FEV1 and maximal oxygen uptake measured at peak exercise.Citation38 Those authors concluded that to capture the overall deterioration in patients’ health status due to COPD, patient-reported outcomes should be followed independently of physical outcomes.Citation38

Challenges in providing chronic care for patients with COPD

During a consultation, patients tend to understate their disease severity, under-report COPD exacerbations, and do not convey the impact of the disease on their quality of life. In addition, patients often only present to their physicians when their condition has progressed significantly leading to a reduced HRQoL.Citation14,Citation39 Consequently, there is a need to assess patients’ health status to enable optimal disease management.

Clinical assessment questionnaires in COPD

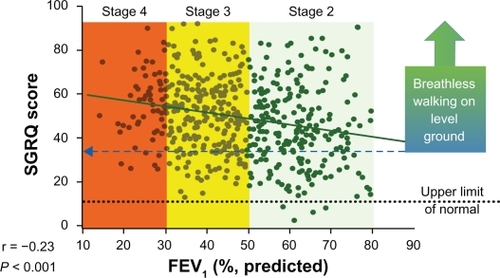

Physicians need to consider several factors when assessing patients with COPD. The impact of COPD depends not only on the degree of airflow limitation but also on the severity of symptoms, systemic effects, and any comorbidities present.Citation2,Citation31 When a patient experiences an exacerbation they often require several weeks of recovery;Citation24 sustained worsening of symptoms can also have a significant impact on patients’ HRQoL and mortality.Citation40–Citation44 Importantly, reductions in objective pulmonary function measurements, such as FEV1, are not well correlated with patients’ perception of symptoms and HRQoL ().Citation17,Citation45 When managing patients with COPD it is therefore necessary to measure both pulmonary function and HRQoL.

Figure 2 Relationship between health status as measured by the SGRQ, and FEV1 and GOLD stage. Patients’ perception of symptoms and health-related quality of life, as assessed by the SGRQ, were not well correlated with objective pulmonary function measurements, such as FEV1 and GOLD stage.

Adapted from Jones PW. Health status measurement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2001;56:880–887 with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group Limited.Citation17

Physicians require help in realizing the full impact of COPD on their patients. Qualitative studies showed that patients with COPD have difficulty placing themselves along a continuum of disease severity and relating their severity to that of other patients with COPD. During development of the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), patients indicated that they would like to have a method available that would allow them to both assess their own disease severity and communicate this information to their physicians.Citation46

Standardized assessments, beyond peak airflow (maximally forced expiration initiated at full inspiration) currently used to assess patients in clinical practice evaluate multidimensional domains (symptoms, physical, psychological, and social) affected by COPD. Examples of disease-specific instruments include the MRC dyspnea scale, the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ), and the CAT.Citation46–Citation48 These measures can be assessed in terms of their relative reliability, validity, responsiveness, acceptability, and feasibility in everyday clinical practice.Citation25 Other questionnaires such as the SGRQ, CRQ, and Short Form 36-item Health Survey (SF-36) comprise many more questions and consequently are not suitable for use in daily clinical practice, so these questionnaires are not discussed further. A comprehensive review of available questionnaires is currently being undertaken by the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (www.theipcrg.org/).

Questionnaires are precision instruments that can provide sensitive and specific information and, if sufficiently short and simple, can enable physicians in routine clinical practice to assess the health status of their patients accurately, thereby allowing improved COPD management.

Medical research council dyspnea scale

The MRC dyspnea scale, recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Citation2 and other national guidelines, was developed by Fletcher et al while studying the respiratory problems of Welsh coalminers in the 1940s.Citation48,Citation49 It is short (comprises five dyspnea items) and has been in use for many years for grading the effect of breathlessness on daily activities. It is simple to administer because it allows patients to indicate the extent to which their breathlessness affects their mobility. However, it only measures one aspect of the patient experience (ie, perceived respiratory disability) and is poorly responsive to change.

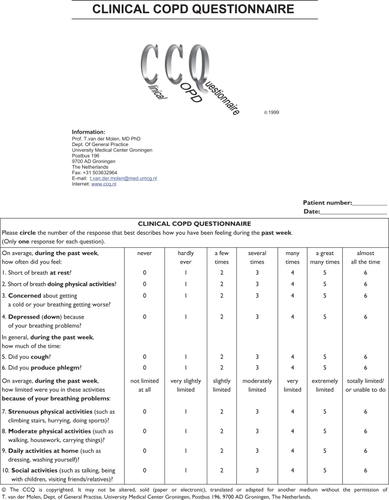

Clinical COPD questionnaire

The CCQ () consists of three domains and 10 items, ie, symptoms (four items), functional state (four items), and mental state (two items). All scores range from 0–6 (0, no impairment).Citation47 The CCQ was developed in consultation with 32 patients in two countries, and item reduction performed in collaboration with 79 clinicians worldwide. Patients can complete the CCQ quickly (in approximately two minutes) and it is straightforward to score; this allows data to be instantly collected and processed, enabling its use in everyday practice, clinical trials, and quality-of-care monitoring. Three studies in the Netherlands, Italy, and Sweden provided strong supporting evidence for the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the CCQ.Citation47,Citation50,Citation51 A change in the total CCQ score of ≥0.4 from one patient visit to the next is considered to be significant (ie, the minimum clinically important difference).Citation52 The CCQ is freely available (in 53 languages) for use in clinical practice (www.ccq.nl).

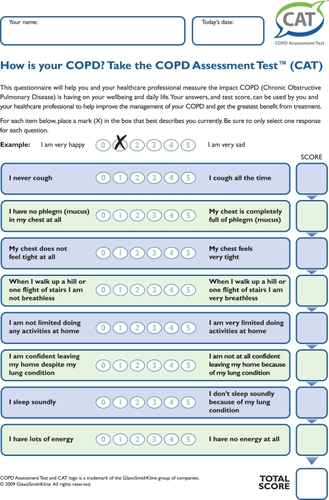

COPD assessment test

The CAT () is a short (eight-item) and simple-to-administer patient-completed questionnaire designed for routine use in clinical practice. It covers a wide range of effects of COPD, including cough and sputum, chest symptoms, activity limitation, sleep, fatigue, and confidence leaving home. Patients can complete the CAT quickly (in approximately two minutes) by themselves in the doctor’s waiting room. Development of the CAT involved consultation with a large number of patients at each stage of the process. Items covered in the CAT can help physicians measure the overall impact that COPD is having on patient wellbeing and daily life. Thus, the CAT provides a holistic measure of COPD health status;Citation46 it should facilitate a fact-based, physician-patient dialog and improve communication to present a common understanding and grading of the impact of COPD. It is supported by strong evidence for reliability and by preliminary data for construct and discriminant validity;Citation46 additional validity analyses are ongoing. The minimum clinically important difference in CAT score is yet to be established formally,Citation53 but based upon mapping from the SGRQ at a population level it will be approximately 1.6 units. At the individual patient level, a change in CAT score of ≥2 units will be clinically significant. The CAT is freely available (although GlaxoSmithKline owns the copyright to protect it from unauthorized changes) for use in daily clinical practice (www.catestonline.org).

Summary

An increased understanding of the full impact of COPD on patients and their carers should enable physicians to provide targeted intervention and improve patients’ HRQoL.

Care for patients with COPD can be optimized best by use of reliable, standardized measurements of overall disease impact. The measures should be appropriate to the question being addressed, sensitive to changes that are relevant to patients, capable of providing physicians with meaningful scores, and acceptable to both patients and health care providers.Citation54 The questionnaires reviewed here have those attributes and are quick and easy to use during consultations. Incorporation of questionnaires such as these into the consultation process will enable improved patient-physician partnership decision-making, help prioritize patients for primary care review, and drive effective management of patients with COPD.

Acknowledgements

Editorial support in the form of development of the manuscript first draft, collating author comments, and referencing was provided by Dr Richard Barry (Quintiles Medical Communications) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Disclosure

PWJ has received consultancy and advisory board fees from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, and Spiration; he has also received lecture fees from GlaxoSmithKline. DP has consultant arrangements with Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, and Teva. He and/or his research team have received grants and support for research in respiratory disease from the following organizations in the past five years: UK National Health Service, Aerocrine, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Nycomed, Pfizer, and Teva. He has spoken for Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Teva. TVDM has participated as a speaker at several conferences financed by ALTANA, GlaxoSmithKline, and AstraZeneca. He has served on the advisory boards for Merck, AstraZeneca, and Nycomed. He has received research grants from ALTANA, AstraZeneca, and MSD.

References

- MathersCDSteinCMa FatDGlobal Burden of Disease 2000: Version 2 methods and resultsGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2002

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (updated 2009)Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease2009 Available from: http://goldcopd.com/. Accessed April 1, 2011.

- MenezesAMPerez-PadillaRHallalPCWorldwide burden of COPD in high- and low-income countries. Part II. Burden of chronic obstructive lung disease in Latin America: The PLATINO studyInt J Tuberc Lung Dis20081270971218544192

- De OcaMMTalamoCHalbertRJFrequency of self-reported COPD exacerbation and airflow obstruction in five Latin American cities: The Proyecto Latinoamericano de Investigacion en Obstruccion Pulmonar (PLATINO) studyChest2009136717819349388

- BuistASVollmerWMMcBurnieMAWorldwide burden of COPD in high- and low-income countries. Part I. The burden of obstructive lung disease (BOLD) initiativeInt J Tuberc Lung Dis20081270370818544191

- BraidoFBaiardiniIMenoniSDisability in COPD and its relationship to clinical and patient-reported outcomesCurr Med Res Opin382011 [Epub ahead of print].

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWHealth-related quality of life in patients by COPD severity within primary care in EuropeRespir Med2011105576620932736

- DecramerMCelliBKestenSEffect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): A prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trialLancet20093741171117819716598

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20103631128113820843247

- JenkinsCRJonesPWCalverleyPMEfficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH studyRespir Res2009105919566934

- ZuWallackRHow are you doing? What are you doing? Differing perspectives in the assessment of individuals with COPDCOPD2007429329717729076

- BuistASMcBurnieMAVollmerWMInternational variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): A population-based prevalence studyLancet200737074175017765523

- Maleki-YazdiMRLewczukCKHaddonJMChoudryNRyanNEarly detection and impaired quality of life in COPD GOLD stage 0: A pilot studyCOPD2007431332018027158

- KornmannOBeehKMBeierJNewly diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical features and distribution of the novel stages of the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung DiseaseRespiration200370677512584394

- JanseAJGemkeRJUiterwaalCSQuality of life: Patients and doctors don’t always agree: A meta-analysisJ Clin Epidemiol20045765366115358393

- RennardSDecramerMCalverleyPMImpact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: Subjects’ perspective of Confronting COPD International SurveyEur Respir J20022079980512412667

- JonesPWHealth status measurement in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax20015688088711641515

- ManninoDMHomaDMAkinbamiLJFordESReddSCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance – United States, 1971–2000MMWR Surveill Summ2002516116

- HansenJGPedersenLOvervadKThe prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among Danes aged 45–84 years: Population-based studyCOPD2008534735219353348

- Domingo-SalvanyALamarcaRFerrerMHealth-related quality of life and mortality in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200216668068512204865

- GudmundssonGGislasonTJansonCRisk factors for rehospitalisation in COPD: Role of health status, anxiety and depressionEur Respir J20052641441916135721

- JonesPLareauSMahlerDAMeasuring the effects of COPD on the patientRespir Med200599Suppl BS11S1816236492

- OgaTNishimuraKTsukinoMSatoSHajiroTAnalysis of the factors related to mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Role of exercise capacity and health statusAm J Respir Crit Care Med200316754454912446268

- SpencerSJonesPWTime course of recovery of health status following an infective exacerbation of chronic bronchitisThorax20035858959312832673

- Patient-reported Health Instruments GroupA structured review of patient-reported measures in relation to selected chronic conditions, perceptions of quality of care and carer impactOxford, UKNational Centre for Health Outcomes Development, Department of Health, University of Oxford2006

- WagnerEHChronic disease management: What will it take to improve care for chronic illness?Eff Clin Pract199812410345255

- AdamsSGSmithPKAllanPFSystematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and managementArch Intern Med200716755156117389286

- BourbeauJvan derPJPromoting effective self-management programmes to improve COPDEur Respir J20093346146319251792

- JonesRCDonaldsonGCChavannesNHDerivation and validation of a composite index of severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The DOSE IndexAm J Respir Crit Care Med20091801189119519797160

- BelzaBSteeleBGCainKSeattle Obstructive Lung Disease Questionnaire: Sensitivity to outcomes in pulmonary rehabilitation in severe pulmonary illnessJ Cardiopulm Rehabil20052510711415818200

- FerrerMAlonsoJMoreraJChronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage and health-related quality of life. The Quality of Life of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Study GroupAnn Intern Med1997127107210799412309

- CarrascoGPde MiguelDJRejasGJNegative impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the health-related quality of life of patients. Results of the EPIDEPOC studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes200643116719899

- FletcherMvan der MolenTSalapatasMWalshJCOPD uncovered: A reportISBN 978-0-95655372009

- AdamsRChavannesNJonesKOstergaardMSPriceDExacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a patients’ perspectivePrim Care Respir J20061510210916701769

- WyrwichKWMetzSMKroenkeKMeasuring patient and clinician perspectives to evaluate change in health-related quality of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Gen Intern Med20072216117017356981

- Confronting COPD in America: Executive Summary http://wwwaarcorg/resources/confronting_copd/exesum.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2011.

- RiesALImpact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on quality of life: The role of dyspneaAm J Med2006119122016996895

- OgaTNishimuraKTsukinoMLongitudinal deteriorations in patient reported outcomes in patients with COPDRespir Med200710114615316713225

- CruseMAThe impact of change in exercise tolerance on activities of daily living and quality of life in COPD: A patient’s perspectiveCOPD2007427928117729073

- KesslerRStahlEVogelmeierCPatient understanding, detection, and experience of COPD exacerbations: An observational, interview-based studyChest200613013314216840393

- MiravitllesMMolinaJNaberanKFactors determining the quality of life of patients with COPD in primary careTher Adv Respir Dis20071859219124350

- CoteCGPinto-PlataVKasprzykKDordellyLJCelliBRThe 6-min walk distance, peak oxygen uptake, and mortality in COPDChest20071321778178517925409

- EstebanCQuintanaJMMorazaJImpact of hospitalisations for exacerbations of COPD on health-related quality of lifeRespir Med20091031201120819272762

- ManninoDMGagnonRCPettyTLLydickEObstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994Arch Intern Med20001601683168910847262

- JonesPWHealth status: What does it mean for payers and patientsProc Am Thorac Soc2006322222616636089

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J20093464865419720809

- Van derMTWillemseBWSchokkerSDevelopment, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD QuestionnaireHealth Qual Life Outcomes200311312773199

- FletcherCMElmesPCFairbairnMBThe significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working populationBr Med J1959225726613823475

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax19995458158610377201

- DamatoSBonattiCFrigoVValidation of the Clinical COPD questionnaire in Italian languageHealth Qual Life Outcomes20053915698477

- StallbergBNokelaMEhrsPOHjemdalPJonssonEWValidation of the clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) in primary careHealth Qual Life Outcomes200972619320988

- KocksJWTuinengaMGUilSMHealth status measurement in COPD: The minimal clinically important difference of the clinical COPD questionnaireRespir Res200676216603063

- Healthcare professional user guideCOPD Assessment Test: Expert guidance on frequently asked questions92009 Available at: http://catestonline.co.uk/images/CAT_Expert%20Guidance_Issue1_2009.pdf. Accessed on April 1, 2011.

- HorneRPriceDClelandJCan asthma control be improved by understanding the patient’s perspective?BMC Pulm Med20077817518999