Abstract

Antibiotics, along with oral corticosteroids, are standard treatments for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). The ultimate aims of treatment are to minimize the impact of the current exacerbation, and by ensuring complete resolution, reduce the risk of relapse. In the absence of superiority studies of antibiotics in AECOPD, evidence of the relative efficacy of different drugs is lacking, and so it is difficult for physicians to select the most effective antibiotic. This paper describes the protocol and rationale for MAESTRAL (moxifloxacin in AECBs [acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis] trial; www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT0656747), one of the first antibiotic comparator trials designed to show superiority of one antibiotic over another in AECOPD. It is a prospective, multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind controlled study of moxifloxacin (400 mg PO [per os] once daily for 5 days) vs amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (875/125 mg PO twice daily for 7 days) in outpatients with COPD and chronic bronchitis suffering from an exacerbation. MAESTRAL uses an innovative primary endpoint of clinical failure: the requirement for additional or alternate treatment for the exacerbation at 8 weeks after the end of antibiotic therapy, powered for superiority. Patients enrolled are those at high-risk of treatment failure, and all are experiencing an Anthonisen type I exacerbation. Patients are stratified according to oral corticosteroid use to control their effect across antibiotic treatment arms. Secondary endpoints include quality of life, symptom assessments and health care resource use.

Introduction

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD), which is usually associated with chronic bronchitis, drive progressive lung function decline in patients,Citation1–Citation3 are major contributors to mortality, morbidity and reductions in quality of life,Citation4–Citation9 and the resulting hospitalizations markedly increase health care costs.Citation7,Citation10 The mainstays of AECOPD treatment are intensification or addition of short-acting bronchodilators, and in selected patients, antibiotics with or without systemic corticosteroids.Citation5,Citation11 However, treatment failure rates in many recent antibiotic studies are high, which could be related to inadequate antibiotic efficacy.Citation12,Citation13 Incomplete resolution of the initial exacerbation may also influence the risk of relapse: many patients experience a further exacerbation within a few weeks,Citation13,Citation14 with relapse rates varying between antibiotics.Citation14 Therefore, it is likely that improving clinical outcomes requires the use of the most effective antibiotic available.

Proof of superiority of one antibiotic over another in AECOPD is lacking,Citation5,Citation11 as are high-quality clinical data to inform clinical guidelines.Citation15,Citation16 Although there are many comparative studies of different antibiotics in AECOPD, no single drug has yet shown superiority for the primary endpoint in a clinical trial. This lack of evidence of superiority is in part because many studies were powered only for noninferiority, but may also be due to issues of patient selection (patient characteristics predating the current exacerbation can negatively affect outcomes) and end-point selection in clinical trials.Citation11,Citation15,Citation17,Citation18

There is a clear unmet need for superiority trials in AECOPD,Citation19 in particular between antibiotics commonly used in AECOPD and in patients at high risk of poor clinical outcomes who are most likely to benefit from the most effective therapies.Citation11,Citation18,Citation19 While trials of antibiotics in AECOPD have yet to show superiority for the primary endpoint, some have demonstrated superiority for secondary endpoints, the most recent of which was the MOSAIC study.Citation20 This compared moxifloxacin and a basket of comparators (amoxicillin/clarithromycin/cefuroxime axetil) in patients with Anthonisen type I exacerbationsCitation21 and mild-to-moderate COPD. In MOSAIC, moxifloxacin was superior to comparator antibiotics for clinical cure (defined as a return to baseline health status) and bacterial eradication. Longer-term outcomes from MOSAIC showed that moxifloxacin was also superior to comparators in terms of lower relapse rates.Citation20

This paper describes the MAESTRAL (moxifloxacin in AECBs [acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis] trial; clinical trial.gov number: NCT0656747) study design and the rationale for its novel features. These include powering the study for superiority testing, selection of chronic bronchitis patients with moderate-to-severe COPD and assessment of the utility of an 8-week clinical endpoint.

MAESTRAL methodology

Study design

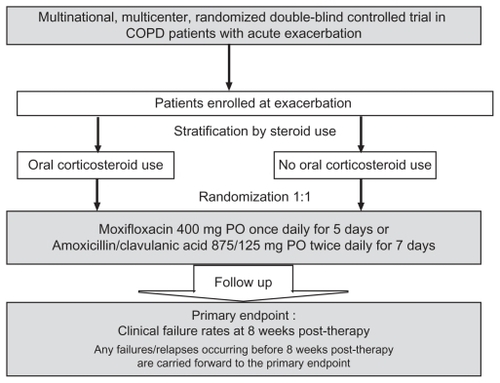

MAESTRAL is a prospective, multinational, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy controlled study. The primary objective of MAESTRAL is to compare the efficacy of a 5-day course of moxifloxacin to that of a 7-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in the treatment of outpatients experiencing AECOPD who are at high risk of treatment failure. The study is powered to show clinical superiority between antibiotic treatments. It uses an innovative clinical endpoint of clinical failure rates over an 8-week period after treatment with an antibiotic. The study design is shown in .

Study population

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Outpatients with COPD and chronic bronchitis suffering from an exacerbation are enrolled in the MAESTRAL study. Patients must be ≥60 years old, have a documented history of ≥2 exacerbations within the previous year requiring a course of systemic antibiotics and/or systemic corticosteroids, postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) ≤60% predicted, FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) <70%, and be current or past cigarette smokers with a ≥20 pack-year smoking history. They must also be experiencing an Anthonisen type I exacerbation (the presence of all three of purulent sputum, increased sputum volume, and increased dyspneaCitation21 as confirmed by the investigator) and be suitable for treatment with oral antibiotics. Patients must also be exacerbation-free for at least 30 days prior to enrollment.

The main exclusion criteria are contraindications to study drugs, immunosuppression, structural lung diseases (for example, known diffuse bronchiectasis), and systemic anti-biotics or corticosteroids within 30 days prior to enrollment. The full list of exclusion criteria is given in .

Stratification by steroid use

To ensure an even distribution between treatment arms of patients receiving corticosteroids, patients are stratified according to the coadministration of a short course (5 days) of systemic corticosteroid therapy (30–40 mg/day of prednisolone or equivalent) for the current exacerbation, where the first dose is administered on the same or next day as the study drug ( and ). Following the end of this 5-day course of steroid treatment, down-titration for up to 5 days is allowed. Agents used to manage the ongoing COPD (long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids) will be maintained on a stable dose and regimen during treatment and for the 8 weeks of follow-up. The choice of steroids is at the treating physician’s discretion within guidelines set out in the study protocol. All comedications will be recorded for the duration of the study.

Ethical approval

All patients must provide written informed consent, according to the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and local legal requirements. The study is being carried out according to Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Documented approval has been obtained from the appropriate ethical committees and Institutional Review Boards.

Microbiology

Spontaneous sputum samples are to be obtained from all patients, assessed in a local laboratory, and examined for the presence of polymorphonuclear cells, squamous epithelial cells, and bacteria. All potentially pathogenic bacteria (PPB) are to be identified (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus spp., Enterobacteriaceae spp., and Staphylococcus aureus) and pure subcultures frozen and subsequently forwarded to a central microbiology laboratory. There, they will be re-identified and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) determined for moxifloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and a range of other antibiotics by the reference Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution method.Citation22 MICs for penicillin are determined for S. pneumoniae, and meticillin resistance is determined in S. aureus.

Antibiotic treatments

Patients receive either moxifloxacin (Bayer Schering Pharma, Wuppertal, Leverkusen or Berlin, Germany) 400 mg PO once daily for 5 days or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (STADApharm GmbH, Bad Vilbel, Germany) 875/125 mg PO twice daily for 7 days. Moxifloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid are well established as effective therapies for exacerbations of COPD and chronic bronchitis with good clinical and bacteriological efficacy in AECOPD.Citation23–Citation25 They are also both included within guidelines as recommended therapies for patients with moderate-to-severe exacerbations.Citation15,Citation16 The dose chosen for both drugs is that recommended in European guidelinesCitation15 and is in common use in the regions where MAESTRAL is being carried out. The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) properties of both drugs suggest that they are an adequate treatment for S. pneumoniae isolates with an MIC ≤2 mg/L.Citation26 Importantly, the dose of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid chosen (875/125 mg PO twice daily for 7 days) has a comparable clinical efficacy and safety profile to a higher dose, shorter course of long-acting amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (2000/125 mg PO twice daily for 5 days).Citation24

Clinical and bacteriological endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint of MAESTRAL is clinical failure at the 8-weeks post-therapy visit. Clinical failure is defined as the requirement for additional or alternate treatment with systemic antibiotics and/or systemic corticosteroids (including increased dose or duration of treatment), and/or hospitalization within 8 weeks post-therapy for an exacerbation of respiratory symptoms. Clinical failures occurring during therapy or follow-up are carried forward until 8 weeks post-therapy. Clinical failures occurring during therapy or follow-up are carried forward until 8 weeks post-therapy.

A range of secondary endpoints is also defined; the full list is given in . These include clinical response rates at interim time points and bacteriological outcome at all time points, lung function tests, medication use, and quality of life (St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ])Citation27 and symptom assessments (Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Bronchitis Symptom Scale [AECB-SS]).Citation28,Citation29

Table 1 Secondary endpoints

Clinical and bacteriological efficacy assessments

The study consists of the following visits: enrollment/randomization (day 1 is the first day of study drug treatment), during therapy (treatment day 4 ± 1), end of therapy (day 13 ± 1 after start of study drug treatment), 4 weeks post-therapy (day 35 ± 3 after start of study drug treatment), and 8 weeks post-therapy (day 63 ± 3 after start of study drug treatment). Data collected at each visit are shown in .

Table 2 Data collected at each study visit

Assessment of clinical response to therapy is based on determination of the effect of therapy on auscultatory findings, chest pain/discomfort, cough frequency, dyspnea, sputum purulence, sputum consistency, and sputum volume. Clinical response is assessed as: clinical improvement (during therapy only), clinical failure, indeterminate, clinical cure, continued clinical cure, and clinical relapse (definitions are given in ). Clinical failure rates can be assessed during nonprotocol-defined visits as well as during therapy, at end of therapy, and at the 4 and 8-week post-therapy visits. Premature discontinuations due to study drug failure will also be treated as failures. For patients who discontinue study drug for reasons other than efficacy, the assessment at 8-week post-therapy visit will be used where completed. For those patients who do not return for the 8-week post-therapy visit, the response will be considered missing. These patients will be excluded from the per protocol population as will those with an indeterminate clinical outcome at the last available assessment.

The categories of bacteriological response to therapy are: eradication without superinfection or reinfection, presumed eradication, persistence, presumed persistence, eradication with superinfection, eradication with reinfection, eradication with recurrence, continued eradication, continued presumed eradication, and indeterminate (see ). Bacteriological response rates are assessed during therapy, at end of therapy and at 4 and 8 weeks post-therapy.

Data Review Committee

There has been some concern in previous antibiotic studies regarding inconsistent assessment of clinical outcomes by treating physicians. To validate the physician’s assessment of clinical outcomes an independent Data Review Committee (DRC) will assess the data for all clinical failures and indeterminate assessments prior to the unblinding of the treatment assignment of datasets. Their objective is to confirm the primary clinical outcome and to validate the inclusion of the patient’s data in the primary analysis.

Safety assessments

The safety of treatment is monitored by clinical observations at each visit following enrollment. All adverse events (AEs) are recorded up to 8 weeks post-therapy. All AEs are assessed in terms of their severity, intensity (mild, moderate or severe), and relationship to the study drug. Investigators are asked to monitor any patients with diarrhea, and if Clostridium difficile-related diarrhea is suspected, investigators are asked to take appropriate clinical measures, including C. difficile toxin detection and remedial therapy where warranted.

Analyses

Efficacy populations

The primary population for assessment of clinical outcomes is the per protocol (PP) population. These patients have all had an acute exacerbation at enrollment and have received the study drug for a minimum of 48 hours (cases of clinical failure) or received ≥80% of study medication (cases of clinical cure). All have data for clinical evaluation at 8 weeks post-therapy (except for clinical failures prior to the 8 weeks post-therapy visit) and have no protocol violations. The intent-to-treat (ITT)/safety population includes all patients randomized who received at least one dose of study drug and with one observation after initiation of study treatment. The microbiologically valid population is drawn from the PP population and comprises all patients with at least one PPB cultured from sputum provided prior to start of therapy and where a bacteriological evaluation is available during the study. The ITT with causative organisms population includes patients valid for ITT with at least one pretherapy PPB.

Statistics

Sample size calculation

To power MAESTRAL for superiority, the objective is to ensure that 540 valid PP patients are enrolled in each treatment arm; therefore, at least 1350 COPD patients with an Anthonisen type I exacerbationCitation21 are required to be randomized. Patients will be drawn from across 30 countries. This high number of patients is driven by a 6% margin – a more rigorous definition of failure rates than the standard 10% normally used in noninferiority trials.Citation30

Primary analysis

The primary aim of the study is to show noninferiority (defined as a difference in failure rates of ≤6% using a one- sided test at a level of 2.5%) of moxifloxacin vs amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in the PP population. If noninferiority is statistically proven, the possibility that moxifloxacin is superior to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid will be tested in the ITT population, using a one-sided test at the 2.5% level. The primary ITT analysis will be clinical failure vs all other evaluations (clinical cure, indeterminate, and missing). Two sensitivity analyses are planned: (1) missing responses will be combined with indeterminates and clinical failures in an overall nonsuccess category, and (2) missing and indeterminate responses will be excluded and only cures or failures will be considered. The 95% two-sided confidence interval (CI) of the difference of two clinical failure rates (treatment group ‘moxifloxacin’ minus treatment group ‘amoxicillin/clavulanic acid’) will be calculated using Mantel–Haenszel weights for the strata (geographic region and stratification by corticosteroid use, as outlined in ). If the upper limit of the CI is <6%, it will prove that treatment with moxifloxacin is clinically no less effective than treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. If the upper limit of this CI is <0, superiority of treatment with moxifloxacin will be proven. To check the appropriateness of the calculation of the Mantel–Haenszel weighted CIs, the Breslow–Day test, or Zelen’s test, will be performed to test for homogeneity of odds ratios across strata. If the test indicates a treatment-by-stratum interaction, exploratory analyses will be performed to find the source of this interaction. If such a source is found, the Mantel–Haenszel weighted CI will be calculated using weighting based on variables explaining the interaction.

Demographic and baseline characteristics will be summarized by treatment group for the PP and ITT populations and compared using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test adjusted for strata and region.

Secondary clinical and bacteriological endpoints will be analyzed as for the primary analysis, but using appropriate patient populations and time points. Clinical and bacteriological outcomes at a variety of time points (during therapy, end of therapy, 4 weeks post-therapy, and 8 weeks post-therapy) will be investigated in subpopulations of special interest, such as those with and without coadministration of systemic corticosteroids. The full list of subpopulations of interest is given in .

AECB-SS and SGRQ scores will be determined and analyzed separately. The main analysis for the SGRQ data will compare the mean change from baseline in the total SGRQ score between treatment groups 8 weeks after the end of therapy. For AECB-SS, the means, standard deviations, medians, minimums, and maximums will be provided for the total score and change from baseline in total score at each visit, by treatment group. For health care resource use, if the homogeneity of between-country resource consumption is satisfactory, the data will be pooled, summarized, and 95% CIs estimated.

For the safety analysis, a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test will assess the difference in incidence rates between treatment groups for the overall rate of premature discontinuations, discontinuations due to AEs, and discontinuations due to insufficient therapeutic effect. Other safety data will be tabulated; vital signs will be analyzed descriptively.

Discussion

Clinical trials of antibiotics in AECOPD have traditionally been short-term, included relatively small numbers of patients, and focused largely on the cure of an existing exacerbation. Most of these trials have been powered to show noninferiority, making it difficult for physicians to select the ‘best’ antibiotic for a particular patient.Citation11,Citation31,Citation32 MAESTRAL aims to address all these issues by recruiting sufficient patients (n ≥1350) to allow the study to be powered for superiority and by setting an innovative long-term primary endpoint of clinical failure at 8 weeks post-therapy.

Traditional clinical trial endpoints occur soon after the end of treatment and cannot provide data on clinical failures or relapse rates occurring more than 2 or 3 weeks post-treatment. Citation11,Citation31 Consequently, they may not be long enough to reveal any clinically relevant differences in treatment regimens that emerge in the weeks following the completion of therapy. Citation33 Indeed, it has been suggested that future clinical trials should be designed to assess longer-term endpoints.Citation34,Citation35 The suitability of an endpoint measured 8 weeks from the end of antibiotic treatment is supported by the fact that patients tend to relapse and exacerbations cluster such that there is a high risk of recurrent exacerbation in the 8 weeks after an initial exacerbation.Citation33 In addition, in the MOSAIC study, the most significant differences between treatments in terms of time-to-treatment failure, relapse, or requirement for further antibiotics occurred during the first 8 weeks after treatment.Citation36

Patient selection is a recurring problem in published trials. It is now well established that underlying patient characteristics such as older age, higher exacerbation frequency, presence of concomitant cardiopulmonary disease, and a higher severity of underlying airway obstruction are key determinants of poor outcome in AECOPD.Citation23,Citation36,Citation37 Exacerbations become more frequent and more severe as the underlying COPD progresses, but some patients have more exacerbations than others, which appears to be an independent susceptibility phenotype.Citation38 Those who are particularly susceptible to exacerbations have worse health status and faster disease progression than infrequent exacerbators.Citation38,Citation39 One explanation might be that some patients remain at high risk for recurrent exacerbation in the 8-week period after initial exacerbation,Citation33 possibly due to differing levels of ongoing lung and systemic inflammation in frequent and infrequent exacerbators.Citation40 In most published antibiotic trials to date, patient populations are highly heterogeneous and may include relatively young and fit patients as well as those who are elderly and/or more severely ill. Indeed, there is even a lack of consensus on how to define patients’ illnesses. While distinctions are made between acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis (AECB) and AECOPD, COPD, and chronic bronchitis often coexist, are treated in parallel in the clinical setting, and most antibiotic intervention studies include patients with and without documented airflow obstruction. Enrollment of patients with AECB, mild COPD, or normal lung function will dilute the actual effect and increase the perceived efficacy of antibiotics due to high spontaneous rates of recovery. This makes it harder to show superiority of one antibiotic over another,Citation11,Citation31 as most of these patients would recover even without an antibiotic. As individuals at high risk of poor outcomes have high rates of failure and relapse,Citation23,Citation41 MAESTRAL is enriched with patients at risk of poor outcomes (ie, those ≥60-years-old who have experienced ≥2 exacerbations in the previous year, have moderate-to-severe COPD according to the GOLD spirometric criteria,Citation16 and who are experiencing an Anthonisen type I exacerbation).

Patients with COPD are likely to be taking a range of medications to treat the exacerbation, the underlying COPD, and any concomitant illness. However, in many trials there is only limited evaluation of concurrent medication, the use of which could affect clinical outcome and create bias between antibiotic treatment groups.Citation31 MAESTRAL tackles this issue by recording all concomitant medications for the full duration of the study. Physicians are instructed not to change patients’ regular maintenance inhaled and oral COPD therapy during the study, but the need for any change in dosage or additional respiratory medication, such as bronchodilators and inhaled steroids, will be assessed.

Treatment of the current exacerbation often requires an antibiotic plus one or more other treatments, such as oral corticosteroids or an increased dose of a long-acting beta-agonist.Citation9,Citation11 To date, whether antibiotics are of benefit in moderate-to-severe exacerbations when a short course of corticosteroids is coadministered has been studied in very few large, well-designed trials.Citation9,Citation11,Citation12 Because steroids can assist in the clinical resolution of an exacerbation, inconstant steroid treatment in the arms of an antibiotic trial can confound interpretation of the results. Mandating oral corticosteroids in all patients or making their use an exclusion criteria in this study are both inconsistent with current guidelines and make recruitment in a large study difficult. In MAESTRAL, the unique approach of stratifying patients for the concomitant use of oral corticosteroids to treat the current exacerbation is used to control for the use of concomitant corticosteroids. However, no inference on the clinical efficacy of steroid treatments can be drawn from this study because the allocation of steroids was not randomized.

Ensuring that patients most likely to be experiencing a bacterial (as opposed to, for instance, viral) exacerbation are enrolled in the trial is an important aspect of the MAESTRAL study design. Therefore, an Anthonisen type I exacerbation must be confirmed by the investigators. Where an AECOPD has a bacterial etiology, symptom resolution of that exacerbation will likely be influenced by bacterial eradication; the underlying mechanism is thought to be due to resolution of the inflammatory response to bacteria.Citation42 By choosing patients with Anthonisen type 1 exacerbations, the study population is enriched with patients in whom bacteria play a significant role and who should benefit most from antibiotic therapy. Anthonisen type I exacerbations have been shown to have a high frequency of bacterial pathogen isolation.Citation4

The MAESTRAL study uses recommended antibiotics, moxifloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Both drugs are commonly used for therapy of more severely ill patients with an AECOPD in most countries where the MAESTRAL trial is conducted, are recommended in a number of guidelines for this patient group,Citation16,Citation43 and have shown good efficacy in AECOPD.Citation23,Citation24 Furthermore there is evidence that fluoroquinolones, such as moxifloxacin, have resulted in better bacteriological eradication than some other drug classes.Citation23 This was seen in the MOSAIC study,Citation20 in which moxifloxacin was equivalent to standard comparators for short-term clinical outcomes, but was superior with respect to bacteriological eradication and resulted in fewer exacerbations in the 8 weeks following treatment than comparators.Citation20 MAESTRAL has built upon the design and outcomes of MOSAIC in a number of ways. As well as using the 8-week endpoint, MAESTRAL enrolls patients identified in a post hoc analysis of MOSAIC data as having a high risk of relapse.

In the majority of noninferiority trials, sample size is calculated in order to detect a difference between treatment groups in failure rates of <10%. Conversely, in MAESTRAL, the high number of patients recruited was driven by a 6% margin for noninferiority, which is a much more rigorous definition. The use of a superiority protocol follows Food and Drug Administration guidance on trial design, which cautions that noninferiority trials have previously failed to show a benefit of one antibiotic over another.Citation44 A further novel element in the design of MAESTRAL is the inclusion of AECB-SS and SGRQ questionnaires. Such patient-reported outcomes can provide important insights into clinical outcomes like symptom improvement and quality of life, as well as providing information that will enable the DRC to make informed decisions about the true clinical outcomes. Use of repeated spirometry measurements in MAESTRAL is also an innovative feature for an antibiotic trial, ensuring that only patients with moderate or severe COPD are enrolled and providing another means of monitoring response to treatment.

DRC members receive patient information in a blinded fashion for those who were clinical failures or had an indeterminate response. Through assessment of all documented clinical information and investigator decisions (although the DRC are blinded to clinical outcome assessments by investigators), the DRC is able to assess whether the patient is a true failure or relapse. This includes going back to investigators via the study managers (ie, in a blinded fashion) to challenge a decision. For example, when the clinical information suggests a clinical relapse, but antibiotic or oral steroid are not prescribed, it may be because the patient attended another clinic; whereas when clinical information suggests stability, but an antibiotic or steroid are prescribed, further questioning of the investigator could reveal that it was not prescribed for a relapse. The DRC also decides, based on prescribing habits, on steroid use that is a violation of protocol vs steroid use that is continued because of persistent symptoms, ie, clinical failure.

There are potential limitations to the design of MAESTRAL. The choice of clinical failure at 8 weeks post-therapy as the primary endpoint is based on the best evidence available, but may not prove to be the optimum duration – potentially an even longer timescale might be desirable. However, it should also be noted that long-term follow-up can be subject to multiple confounders. Additionally, while steps have been taken to control for concomitant medications and oral corticosteroid use, stratification was limited to corticosteroid use and not undertaken for the use of long-acting bronchodilator and/or inhaled corticosteroids (though the inhaled medications were used at a stabilized dose).

Despite these limitations, it is anticipated that MAESTRAL will provide further evidence as to the most appropriate study design for trials of antibiotics in AECOPD, and it should also provide some information about the extent of the relative roles of antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of AECOPD. Irrespective of whether noninferiority or superiority is achieved, the results should add further to the debate on optimal trial design in this condition. It is hoped that MAESTRAL may also help to inform guidelines and allow physicians to optimize clinical outcomes and reduce AECOPD-related health care costs through appropriate patient profiling and antibiotic choice.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Highfield Communication Consultancy (funded by Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals) provided editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. RW was supported by the NIHR Respiratory Disease Biomedical Research Unit.

Supplementary material

Supplementary section 1 Full list of exclusion criteria

Supplementary section 2 Protocol for stratification according to steroid use and geographical region

Supplementary section 3 Clinical and bacteriological response categories

Supplementary section 4 Subpopulations of interest

Disclosure

RW, SS, AA, and MM have acted as consultants and received honoraria as speakers in scientific meetings or courses organized by the study sponsor. PA and DH are employees of Bayer HealthCare and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals (France and USA, respectively). MT and GF are employees of Bayer Inc, Canada.

References

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTABhowmikAWedzichaJARelationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2002571084785212324669

- KannerREAnthonisenNRConnettJEfor the Lung Health Study Research GroupLower respiratory illnesses promote FEV(1) decline in current smokers but not ex-smokers with mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the lung health studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2001164335836411500333

- MartinezFJHanMKFlahertyKCurtisJRole of infection and antimicrobial therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseExpert Rev Anti Infect Ther20064110112416441213

- Soler-CatalunaJJMartínez-GarcíaMARomán SánchezPSevere acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622

- AnzuetoASethiSMartinezFJExacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc20074755456417878469

- RamseySDHobbsFDChronic obstructive pulmonary disease, risk factors, and outcome trials: comparisons with cardiovascular diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc20067363564016963547

- NiewoehnerDEThe impact of severe exacerbations on quality of life and the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Med200611910 Suppl 1S3845

- LlorCMolinaJNaberanKCotsJMRosFMiravitllesMfor the EVOCA study groupExacerbations worsen the quality of life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in primary healthcareInt J Clin Pract200862458559218266710

- WilkinsonTWedzichaJAStrategies for improving outcomes of COPD exacerbationsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20061333534218046870

- DalalAAChristensenLLiuFRiedelAADirect costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among managed care patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010534134921037958

- SethiSMurphyTFAcute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: new developments concerning microbiology and pathophysiology – impact on approaches to risk stratification and therapyInfect Dis Clin North Am200418486188215555829

- DanielsJMSnijdersDde GraaffCSVlaspolderFJansenHMBoersmaWGAntibiotics in addition to systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010181215015719875685

- AaronSDVandemheenKLHebertPOutpatient oral prednisone after emergency treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2003348262618262512826636

- AdamsSGMeloJLutherMAnzuetoAAntibiotics are associated with lower relapse rates in outpatients with acute exacerbations of COPDChest200011751345135210807821

- WoodheadMBlasiFEwigSEuropean Respiratory SocietyEuropean Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infectionsEur Resp J200526611381180

- The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD Available at: http://goldcopd.comAccessed April 4, 2011

- DeverLLShashikumarKJohansonWGJrAntibiotics in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitisExpert Opin Investig Drugs2002117911925

- SethiSAntibiotics in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitisExpert Rev Anti Infect Ther20108440541720377336

- MiravitllesMTorresANo more equivalence trials for antibiotics in exacerbations of COPD, pleaseChest2004125381181315006934

- WilsonRAllegraLHuchonGfor the MOSAIC Study GroupShort- term and long-term outcomes of moxifloxacin compared to standard antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitisChest2004125395396415006954

- AnthonisenNRMaanfredaJWarrenCPHershfieldESHardingGKNelsonNAAntibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med198710621962043492164

- Clinical Laboratory Standards InstituteMethods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standards8th Edition CLSI document M07-A8Wayne, PA2009

- MiravitllesMMoxifloxacin in the management of exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20072319120418229559

- SethiSBretonJWynneBEfficacy and safety of pharmacokinetically enhanced amoxicillin-clavulanate at 2000/125 milligrams twice daily for 5 days versus amoxicillin-clavulanate at 875/125 milligrams twice daily for 7 days in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitisAntimicrob Agents Chemother200549115316015616290

- WhiteARKayeCPoupardJAugmentin® (amoxicillin/clavulanate) in the treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infection: a review of the continuing development of an innovative antimicrobial agentJ Antimicrob Chemother200453Suppl 1i3i2014726431

- Summary of Product CharacteristicsAvelox 400 mg film-coated tabletsBayer Schering PharmaBayer UK Available at: http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/11841/SPC/Avelox+400+mg+film-coated+tabletsAccessed April 4, 2011

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMThe St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireRespir Med199185Suppl B2531 discussion 33–371759018

- JonesPWActivity limitation and quality of life in COPDCOPD20074327327817729072

- JonesPWThe Acute Exacerbation of COPD Symptom Scale (AECB-SS)J COPD Management2006 Quarter 2, article 3

- Food and Drug AdministrationGuidance for Industry Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials Additional2010 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM202140.pdfAccessed April 4, 2011

- PatelAWilsonRNewer fluoroquinolones in the treatment of acute exacerbations of COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20061324325018046861

- SiddiqiASethiSOptimizing antibiotic selection in treating COPD exacerbationsInt J Chron Obstruc J Pulmon Dis2008313144

- HurstJRDonaldsonGCQuintJKTemporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179536937419074596

- AnzuetoARizzoJAGrossmanRFThe infection-free interval: its use in evaluating antimicrobial treatment of acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitisClin Infect Dis19992861344134510451195

- ChodoshSClinical significance of the infection-free interval in the management of acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitisChest200512762231223615947342

- WilsonRJonesPSchabergTfor the MOSAIC Study GroupAntibiotic treatment and factors influencing short and long term outcomes of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitisThorax200661433734216449273

- MiravitllesMGuerreroTMayordomoCFactors associated with increased risk of exacerbation and hospital admission in a cohort of ambulatory COPD patients: a multiple logistic regression analysis. The EOLO Study GroupRespiration200067549149211185489

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoAfor the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) InvestigatorsSusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- WedzichaJASeemungalTACOPD exacerbations: defining their cause and preventionLancet2007370958978679617765528

- PereraWRHurstJRWilkinsonTMInflammatory changes, recovery and recurrence at COPD exacerbationEur Respir J200729352753417107990

- DewanNARafiqueSKanwarBAcute exacerbation of COPD: factors associated with poor treatment outcomeChest2000117366267110712989

- WhiteAJGompertzSBayleyDLResolution of bronchial inflammation is related to bacterial eradication following treatment of exacerbations of chronic bronchitisThorax200358868068512885984

- O’DonnellDEAaronSBourbeauJCanadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – 2007 updateCan Respir J200714Suppl B5B32B

- Food and Drug AdministrationGuidance for IndustryAcute Bacterial Exacerbations of Chronic Bronchitis in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Developing Antimicrobial Drugs for Treatment2008 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm070935.pdfAccessed April 4, 2011