Abstract

Background

Few estimates of health care costs related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are available regarding commercially insured patients in the United States. The aims of this retrospective observational analysis of administrative data were to describe and compare health care resource use and costs related to COPD in the United States for patients with commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage with Part D benefits, and to assess cost trends over time.

Methods

Patient-level and visit-level health care costs in the calendar years 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2009 were assessed for patients with evidence of COPD. Generalized linear models adjusting for sex, age category, and geographic region were used to investigate cost trends over time for patients with Medicare or commercial insurance.

Results

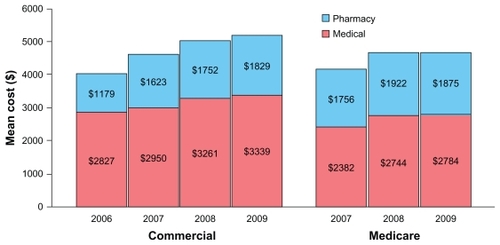

Medical costs, which ranged from an annual mean of US$2382 (Medicare 2007) to US$3339 (commercial 2009) per patient, comprised the majority of total costs in all years for patients with either type of insurance. COPD-related costs were less for Medicare than commercial cohorts. In the multivariate analysis, total costs increased by approximately 6% per year for commercial insurance patients (cost ratio 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.07; P < 0.001) and 5% per year for Medicare patients (cost ratio 1.05; 95% CI 1.03–1.07; P < 0.001). Costs for outpatient and emergency department visits increased significantly over time in both populations. Standard admission costs increased significantly for Medicare patients (cost ratio 1.03; 95% CI 1.00–1.05; P = 0.03), but not commercial patients, and costs for intensive care unit visits remained stable for both populations.

Conclusion

COPD imposed a substantial economic burden on patients and the health care system, with costs increasing significantly in both the Medicare and commercial populations.

Keywords:

Introduction

Chronic lower respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) represent a substantial portion of the burden of chronic illness in the United States (US). In 2008, chronic lower respiratory diseases surpassed stroke to become the third leading cause of death in the US,Citation1 and the US ranked second highest in COPD mortality in 2007 compared with 16 industrialized countries.Citation2 Projections suggest that the global ranking of COPD mortality will rise relative to other causes over the next 20 years.Citation3 In a study of chronic diseases among Medicare beneficiaries in 2005, patients with evidence of COPD comprised a greater proportion of the population Original Research than patients with cancer (breast, colorectal, prostate, and lung cancer combined) or chronic kidney disease.Citation4

COPD is a progressive respiratory disease defined by airflow limitation.Citation5 The working definition set forth by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) states: “COPD is a preventable and treatable disease with some significant extrapulmonary effects that may contribute to the severity in individual patients. Its pulmonary component is characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. The airflow limitation is usually progressive and associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lung to noxious particles or gases.”Citation5 In addition to these defining characteristics, patients also exhibit chronic dyspnea and bronchitis, cough, sputum production, and pathologic features of emphysema. Patients with moderate to severe COPD have periods of symptom worsening superimposed on overall disease progression. These exacerbations negatively affect patient quality of life.Citation6,Citation7

Aims of managing stable COPD include reducing the frequency and severity of exacerbations as well as controlling baseline symptoms.Citation5,Citation8,Citation9 Maintenance medications, including bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids, combination medications, and oxygen therapy for severe COPD are primarily used at home. Hospitalization is common for patients experiencing a severe exacerbation.Citation5,Citation10,Citation11 Severe exacerbations might be managed in an inpatient or emergency department (ED) setting, but life-threatening exacerbations may require immediate intensive care unit (ICU) admission.Citation5

The high prevalenceCitation2,Citation3,Citation12–Citation14 and morbidity of COPD contributed to a projected US$29.5 billion in related direct costs in 2010 in the US.Citation2 In an analysis of commercially insured patients in the US in 2006, the mean annual COPD-related health care cost per patient was estimated to range from US$2003 to US$43,461 (2008 cost year), depending on the level of care received.Citation15 Mean hospital costs for visits associated with exacerbations in 2008 were estimated to range up to US$44,909 for ICU admissions that required intubation; this value increased to US$45,607 when only Medicare beneficiaries were included in the analysis.Citation16,Citation17 In a study of Medicare beneficiaries in 2005, the mean annual payment per patient with COPD, estimated as US$21,409, exceeded average payments for patients with heart failure, depression, cancer, or diabetes.Citation4 This study of Medicare costs covered a period prior to the implementation of the Part D pharmacy benefit, and thus does not reflect pharmacy costs.

Hospitalization is a significant aspect of the burden of COPD. US national survey data indicate that hospitalizations for COPD have increased since 1990, reaching 23.6 per 10,000 population in 2005.Citation18 Discharge data from US hospitals in 2007 showed that COPD accounted for 26.1 hospitalizations per 10,000 population aged 45–64 years; this rate was similar to that reported for diabetes and pneumonia in this age group.Citation19 For patients aged 65–74 years, however, the hospitalization rate for COPD more than tripled to 92.6 per 10,000 population – similar to pneumonia but exceeding diabetes in this age group.Citation19 In addition, Medicare beneficiaries with COPD had more inpatient stays and days than patients with cancer, diabetes, or heart failure in 2005.Citation4

Hospitalization is a major cost driver in COPD management overallCitation2,Citation15,Citation20 and is a primary component of exacerbation costs.Citation21 Hospital care was projected to account for 45% of direct COPD costs in the US in 2010, whereas prescription drugs comprised approximately 20%.Citation2 Inpatient care accounted for approximately 80% of excess costs for COPD patients in a matched comparison of Medicare beneficiaries with and without COPD in 2004.Citation22 Because of the link between exacerbations and hospitalization, reducing exacerbation frequency or severity could reduce COPD-related hospitalizations and thereby reduce costs.Citation23,Citation24

Disease-management initiatives have potential to reduce health care costs associated with COPD.Citation25 In order to assess the effect of such initiatives, a benchmark is needed for comparison. The objectives of this study are to provide a baseline estimate of costs of COPD-related care for patients in the US, including those on Medicare Advantage plus Part D or with commercial insurance, and to assess cost trends over time.

Material and methods

Data source

Medical, pharmacy, and enrolment data from a large US health care claims database affiliated with OptumInsight (formerly Innovus) were used in this retrospective study. Data from commercial and Medicare Advantage populations were used. No identifiable protected health information was extracted or accessed during the course of the study. Pursuant to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act,Citation26 the use of de-identified data does not require Institutional Review Board approval or waiver of authorization.

Patient selection

Eligible patients had either commercial (employer-based) insurance or Medicare Advantage with Part D benefits. Patients were selected for inclusion in the study based on evidence of COPD-related health service utilization during at least one of the calendar years of interest (2006 through 2009). Evidence of COPD-related care was based on medical and pharmacy claims. Specifically, patients were included if they fulfilled one of three criteria during a year of interest: (1) ED or inpatient facility claim with COPD (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 491, 491.0, 491.1, 491.2x, 491.8, 491.9, 492, 492.0, 492.8, or 496) in the primary diagnosis position (for an inpatient stay, the diagnosis code must have been on a hospital claim); or (2) an outpatient claim with a primary diagnosis of COPD and a second outpatient medical claim with a COPD diagnosis in any position on a separate service date; or (3) a physician claim with a primary or secondary (any position other than primary) diagnosis of COPD and a filled prescription for a COPD maintenance treatment (ie, anticholinergic, long-acting beta agonist [LABA], or inhaled corticosteroid/LABA combination). Patients were also required to be at least 40 years of age as of the cohort year and to be continuously enrolled in the health plan with both medical and pharmacy benefits for the calendar year of interest.

Claims dated in the years 2006 through 2009 for patients with commercial insurance and years 2007 through 2009 for patients with Medicare Advantage plus Part D were included in the analysis. The analysis started in 2007 for the Medicare population because use of the Part D benefit may have been inconsistent or unrepresentative in 2006, the first year it was implemented. Study cohorts were formed based on insurance type and the calendar year of service: 2006, 2007, 2008, or 2009. Patient follow-up covered each discrete calendar year; ie, individual patients were not followed longitudinally from year to year although they may have been included in more than 1 year-based cohort if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria in more than 1 year.

Data regarding patient characteristics were collected from enrolment information and claims. These included age, sex, geographic region, and evidence of comorbidities such as asthma. Diagnosis of asthma (ICD-9-CM 493.xx), chronic bronchitis (491.xx), emphysema (492.xx), or chronic airway obstruction not elsewhere classified (496.xx) in any position during the year was noted, and comorbidity burden was quantified using the Quan-Charlson comorbidity score.Citation27

Cost calculations

COPD-related costs were tabulated in each year of interest based on total paid amounts, including patient- and health plan-paid amounts. Use of actual paid costs provides a view of the true costs of COPD incurred by payers and patients. Costs for commercially insured patients include estimated Medicare or other payer contributions based on coordination of benefits information. All costs were adjusted to 2008 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.Citation28

Medical costs comprise costs for COPD-related visits, other related medical services (ie, from claims with COPD diagnosis in the primary position that did not fall into specified visit categories), and oxygen use. COPD-related visits included outpatient, urgent outpatient, and ED visits, as well as standard admissions (no ICU) and ICU stays. An “outpatient” visit was defined as a medical claim for office or outpatient care with COPD indicated in the primary or secondary position, but no evidence of an “urgent” visit (defined below). Outpatient care included physician office visits, outpatient hospital services, laboratory visits, and urgent care center visits. An “urgent outpatient” visit was based on a medical claim for outpatient care for COPD (primary or secondary position) followed by a pharmacy claim for an oral corticosteroid or antibiotic within 7 days after the visit. An “ED” visit was based on a medical claim for an ED visit for COPD (primary position). A “standard admission” was based on an inpatient stay for COPD (diagnosis in the primary position on a hospital claim), but no evidence of ICU treatment during the stay. “ICU” care was defined as a medical claim during an inpatient stay with revenue code of 020x, 021x, 0223, or 0234 or a current procedural terminology (CPT) procedure code for critical care (99291–99292). Oxygen use was identified by medical procedure (CPT/HCPCS E0424–E0444, E0445, E0455, E0550, E0560, E1353–E1372, E1399, K0740; ICD-9 93.96), diagnosis (ICD-9 V46.2), and facility revenue codes (0277, 0544, 060x).

COPD-related pharmacy costs were summed from pharmacy claims for any of the following medications: short-acting beta agonists, LABAs, anticholinergics, methylxanthines, oral/intravenous corticosteroids, inhaled corticosteroids, inhaled corticosteroid/LABA combinations, other respiratory medications, or antibiotics.

Patient- and visit-level analyses

Patient-level costs were calculated as the sum of costs during the year of interest and reported as the mean annual cost among patients in the year-based cohort. COPD-related medical and pharmacy costs are reported separately in the patient-level analysis, and total COPD-related health care costs are the sum of COPD-related medical and pharmacy costs. Visit-level costs were calculated based on all visits of a given type during the year and are reported as the mean cost per COPD-related care episode. Multivariate models were used to assess patient-level and visit-level cost trends over time.

COPD-related hospital readmissions were also assessed. COPD-related readmissions were defined as COPD-related hospital stays (primary diagnosis of COPD) that occurred after the initial COPD-related admission (ie, patients who had more than one COPD-related hospital stay in the study year were considered to have a readmission). The percentages of patients with readmissions within 30 days and 60 days of the initial admission are also reported. ED visits were not considered in the assessment of readmissions.

Statistical analysis

Patient- and visit-level costs are reported with descriptive statistics. Trends over time were investigated with generalized linear models with gamma distribution and log link to account for the skewed distribution of costs.Citation29 The models adjusted for sex, age category, and geographic region, with year as the primary predictor. The models did not adjust for comorbidity because changes in costs for COPD care year over year might be related to management of associated comorbid conditions. The authors did not want to “control away” differences in comorbid status that are clinically associated with COPD. A threshold of P < 0.05 was used to define statistical significance. The multivariate models were fit by Stata 10.0 (Stata-Corp, College Station, TX) software, and all other analyses were conducted using SAS® 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

Demographics and comorbidities of the commercial and Medicare Advantage COPD patient cohorts in 2009 are shown in . Characteristics of the patient cohorts from years 2006 through 2008 are shown in . Across each year studied, demographic characteristics of commercial cohorts were similar to each other and characteristics of Medicare Advantage cohorts were similar to each other. The highest proportion of patients was from the South region for all commercial and Medicare Advantage cohorts, which reflects the distribution of patients in the overall database population. In each year studied, the mean age of the Medicare Advantage cohort was approximately 10 years older than that of the commercial cohort, as expected.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and commercial insurance or Medicare

Within each year, the proportions of patients with the respiratory comorbidities noted in were similar between the commercial and Medicare Advantage samples. Patients in the Medicare cohort had more comorbidities than the commercial cohort as evidenced by higher mean Quan-Charlson comorbidity index score. This relationship held true over time. Approximately 30% of patients in the commercial and Medicare Advantage cohorts in each year had evidence of comorbid asthma.

Patient-level costs of COPD

Mean annual COPD-related health care costs for each commercial insurance and Medicare Advantage cohort are shown in . Medical costs, which comprise amounts paid for facility and physician services, accounted for the majority of total costs in all cohorts. COPD-related medical costs were approximately 16%–19% lower for Medicare than commercial cohorts, and total costs were approximately 7%–10% lower for Medicare than commercial cohorts in each year that both insurance types were studied.

Figure 1 Mean annual unadjusted patient-level chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related health care costs for patients with commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage.

Based on the multivariate analysis, total costs increased over time for both Medicare Advantage and commercial insurance patients after adjustment for age, sex, and region. The rate of increase for total costs was approximately 6% per year for commercial insurance patients and 5% per year for Medicare Advantage patients (). Both pharmacy and medical costs increased significantly over time for the commercial population, but only medical costs increased significantly for the Medicare Advantage population (). Pharmacy costs accounted for a small proportion of total COPD costs for both cohorts.

Table 2 Adjusted chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related subject-level and visit-level cost ratios with year as primary predictor

For Medicare Advantage patients, mean (and standard deviation) cost associated with oxygen use increased from US$758 (US$3595) in 2007 to US$871 (US$3095) in 2009. Over the same time period, mean cost associated with oxygen use increased from US$459 (US$2155) to US$501 (US$2897) for patients with commercial insurance.

Visit-level costs of COPD

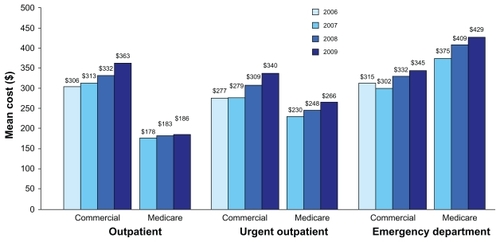

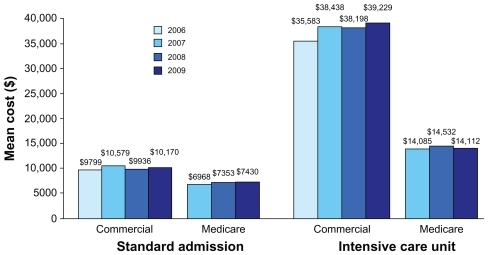

Mean costs of nonhospital COPD-related visits by year and insurance type are shown in , and costs of standard admissions and ICU visits are shown in . Commercially insured patients accounted for greater costs than Medicare Advantage patients for ambulatory visits, standard admissions, and ICU care, whereas Medicare patients accounted for greater ED costs than commercial patients. Cost values are shown in .

Figure 2 Mean unadjusted visit-level costs of nonhospital chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related visits in 2006 through 2009 for patients with commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage.

Note: Costs are adjusted to year 2008 and are in USD.

Figure 3 Mean unadjusted visit-level costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related standard admission (no intensive care unit) and intensive care unit visits in 2006 through 2009 for patients with commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage.

After adjustment for age, sex, and region; costs for outpatient, urgent outpatient, and ED visits increased significantly over time in both populations (). The rate of increase for outpatient visit costs was approximately 6% per year for commercial patients, but only 2% per year for Medicare Advantage patients (). Costs for standard admissions increased significantly over time for patients with Medicare, but not for those with commercial insurance, and costs for ICU care remained stable for both populations.

COPD readmissions

Among patients with a standard admission or ICU stay (eg, in 2009, 7.5% [3852/51,210] of commercially insured patients and 10.7% [4511/42,166] of Medicare Advantage patients had at least one inpatient visit), the proportion with a readmission during the study year ranged from 13%–14% for the commercial population and 16%–19% for the Medicare Advantage population, depending on the year (2006–2009). Of all readmit visits among commercially insured patients, approximately 31%–34% (depending on the year) occurred within 30 days of the initial admission and 47%–49% occurred within 60 days (the number of readmit visits within 60 days includes the number that occurred within 30 days of the initial admission). Similarly, 30%–32% (depending on the year) of readmit visits among Medicare Advantage patients occurred within 30 days of the initial admission, and 49%–52% occurred within 60 days.

Discussion

Annual per-patient COPD-related total direct health care costs increased over time: by approximately 6% per year for commercially insured patients from 2006 through 2009 and 5% per year for Medicare Advantage patients from 2007 through 2009, after adjustment. Medical costs accounted for the majority of patient-level costs among both commercially insured patients and those with Medicare. Costs per inpatient care episode were substantial and relatively stable, except for an increase in standard admission costs for Medicare Advantage patients.

Hospital-perspective data from 2005 through 2008 produced similar visit-level results.Citation16 Relative to 2005, hospital costs for a standard admission were 6%–11% higher and ED costs were 4%–10% higher over the period 2006 through 2008, but a consistent upward trend was not evident.Citation16 Hospital costs for encounters with ICU or intubation varied by less than 3% from 2005 through 2008,Citation16 which is consistent with the findings of this present study that total payer- and patient-paid ICU costs did not increase significantly over the studied period. Notwithstanding this lack of increase, ICU stays were expensive for both the commercial and Medicare Advantage populations. ICU visit costs for commercially insured patients were more than double the costs for patients on Medicare Advantage. Possible reasons for this discrepancy include Medicare cost control and the difference in age between the populations. The commercial patients were younger on average, and it is possible that younger patients receive more aggressive or costly care independent of insurance type. However, this study did not address these possible explanations and additional research is needed.

It would be of interest to compare costs between Medicare and commercial enrollees aged 65 and older, but cost differences are difficult to parse out due to differences in the populations as well as because of how costs are calculated. The age 65 and older commercial population consists of patients still working, retirees, and patients with spouses who retain commercial insurance. Because commercial benefits are coordinated with Medicare, costs (primarily for hospitalization services, but in some cases for Part B services) are necessarily calculated using an estimator of the contribution of Medicare to paid amounts. Addressing this complex issue was beyond the scope of the study.

The data provide a benchmark for assessing the impact of changes in COPD management practices. Because ICU stays and hospitalizations for patients with COPD can often be the result of exacerbations, reducing the frequency of severe exacerbations could help to control COPD-related costs. Treatments that reduce the frequency of COPD-related hospitalizations or exacerbationsCitation11 are also associated with lower COPD-related medical costs, and in some cases lower total COPD-related costs.Citation30,Citation31 Additional research is needed to investigate the interrelationships among treatment for COPD, risk of exacerbation and hospitalization, and costs.

Like previous studies, patients in this present analysis had a high rate of readmissions, and many of these visits occurred within a month of the index visit. An analysis of Medicare claims from 2003 through 2004 reported a readmission rate of 23% for patients with an initial admission for COPD.Citation32 Patients with an initial COPD-related admission accounted for 4% of all rehospitalizations observed in that study, and COPD was the third most common index condition associated with rehospitalization, after heart failure and pneumonia.Citation32 Records from five New York City hospitals indicate that 22% of hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations in a 2-year period are repeat admissions; 17.6% of patients are readmitted at least once.Citation33 Hospital data from 2008 indicate that between 15% and 18% of patients with an initial ED or inpatient visit for COPD have a repeat visit within 60 days.Citation16,Citation17 Given the high rate of hospitalization of patients with COPD, interventions aimed at reducing the need for COPD-related admissions and readmissions may help to lessen resource use and costs for this patient population.

Like all retrospective claims-based studies, this study is limited by constraints of the data source, and results must be interpreted in the context of these limitations. Claims are collected for payment, not research, and coding errors are possible. Although this present analysis included only direct costs, indirect costs of COPD are also substantial,Citation2,Citation23,Citation34 and the results of this present study are likely to underestimate the overall burden of COPD. Clinical measures of COPD severity were not available in the dataset, and thus the influence of severity on annual or visit costs could not be determined. The results might not generalize to uninsured patients or patients in areas with limited access to medical care. Finally, each calendar year-based cohort was identified separately – patients were not examined longitudinally – and there is overlap between cohorts from year to year.

Conclusion

The economic burden of COPD on patients and payers grew from 2006 through 2009, and much of these costs are attributable to medical expenses. This information can be used to evaluate the effect of changes in the practice of COPD management. Improved symptom management could reduce demand for high-cost medical resources, such as ICU care, and reduce overall COPD-related costs.

Acknowledgment/disclosure

Anand Dalal is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. All other authors are employees of OptumInsight (formerly Innovus), which was contracted by GlaxoSmithKline to conduct the study. Elizabeth J Davis, PhD, OptumInsight, Eden Prairie, MN, provided medical writing assistance.

References

- MininoAMXuJKochanekKDDeaths: preliminary data for 2008Natl Vital Stat Rep2010592 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_02.pdfAccessed August 23, 2011

- National Heart Lung and Blood InstituteMorbidity and mortality: chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases2009 Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htmAccessed August 23, 2011

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- SchneiderKMO’DonnellBEDeanDPrevalence of multiple chronic conditions in the United States’ Medicare populationHealth Qual Life Outcomes200978219737412

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD2010 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed August 23, 2011

- LlorCMolinaJNaberanKCotsJMRosFMiravitllesMExacerbations worsen the quality of life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in primary healthcareInt J Clin Pract200862458559218266710

- AnzuetoALeimerIKestenSImpact of frequency of COPD exacerbations on pulmonary function, health status and clinical outcomesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009424525119657398

- CelliBRMacNeeWStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J200423693294615219010

- National Collaborating Centre for Chronic ConditionsChronic obstructive pulmonary disease. National clinical guideline on management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary careThorax200459Suppl 11232

- SteinBDCharbeneauJTLeeTAHospitalizations for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: how you count mattersCOPD20107316417120486814

- SeemungalTStockleyRCalverleyPHaganGWedzichaJAInvestigating new standards for prophylaxis in reduction of exacerbations – the INSPIRE study methodologyCOPD20074317718317729060

- ManninoDMHomaDMAkinbamiLJFordESReddSCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance – United States, 1971–2000MMWR Surveill Summ2002516116

- HalbertRJNatoliJLGanoABadamgaravEBuistASManninoDMGlobal burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysisEur Respir J200628352353216611654

- BuistASMcBurnieMAVollmerWMInternational variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence studyLancet2007370958974175017765523

- DalalAAChristensenLLiuFRiedelAADirect costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among managed care patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010534134921037958

- DalalAAShahMD’SouzaAORanePCosts of COPD exacerbations in the emergency department and inpatient settingRespir Med2011105345446020869226

- DalalAAShahMD’SouzaAORanePCosts of inpatient and emergency department care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in an elderly Medicare populationJ Med Econ201013459159820854113

- BrownDWCroftJBGreenlundKJGilesWHTrends in hospitalization with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – United States, 1990–2005COPD201071596220214464

- National Center for Health StatisticsHealth, United States, 2010 with special feature on death and dyingHyattsville, MD2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus10.pdf#100Accessed August 23, 2011

- WoutersEFEconomic analysis of the Confronting COPD survey: an overview of resultsRespir Med200397Suppl CS3S1412647938

- ToyELGallagherKFStanleyELSwensenARDuhMSThe economic impact of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and exacerbation definition: a reviewCOPD20107321422820486821

- MenzinJBoulangerLMartonJThe economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a US Medicare populationRespir Med200810291248125618620852

- HalpernMTStanfordRHBorkerRThe burden of COPD in the USA: results from the Confronting COPD surveyRespir Med200397Suppl CS81S8912647946

- MapelDWSchumMLydickEMartonJPA new method for examining the cost savings of reducing COPD exacerbationsPharmacoeconomics201028973374920799755

- ChuangCLevineSHRichJEnhancing cost-effective care with a patient-centric coronary obstructive pulmonary disease programPopul Health Manag201114313313621214417

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 Public law 104–191104th Congress. US Department of Health and Human Services1996 Available from: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HIPAAGenInfo/Downloads/HIPAALaw.pdfAccessed August 23, 2011

- QuanHSundararajanVHalfonPCoding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative dataMed Care200543111130113916224307

- US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor StatisticsConsumer Price IndexChained consumer price index for all urban consumers (C-CPI-U) 1999–2008, Medical Care Series ID: SUUR0000SAMWashington, DCUS Department of Labor2008 Available from: http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?suAccessed August 23, 2011

- ManningWGThe logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problemJ Health Econ199817328329510180919

- AkazawaMHayflingerDCStanfordRHBlanchetteCMEconomic assessment of initial maintenance therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Manag Care200814743844818611095

- DalalAAPetersenHSimoni-WastilaLBlanchetteCMHealthcare costs associated with initial maintenance therapy with fluticasone propionate 250 mug/salmeterol 50 mug combination versus anticholinergic bronchodilators in elderly US Medicare-eligible beneficiaries with COPDJ Med Econ200912433934719827993

- JencksSFWilliamsMVColemanEARehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service programN Engl J Med2009360141418142819339721

- YipNHYuenGLazarEJAnalysis of hospitalizations for COPD exacerbation: opportunities for improving careCOPD201072859220397808

- GerdthamUGAnderssonLFEricssonAFactors affecting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-related costs: a multivariate analysis of a Swedish COPD cohortEur J Health Econ200910221722618853206

Appendix tables

Appendix 1 Characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by insurance type

Appendix 2 Unadjusted visit-level costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related visits in 2006 through 2009 for patients with commercial insurance or Medicare Advantage