Abstract

Current primary care patterns for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) focus on reactive care for acute exacerbations, often neglecting ongoing COPD management to the detriment of patient experience and outcomes. Proactive diagnosis and ongoing multifactorial COPD management, comprising smoking cessation, influenza and pneumonia vaccinations, pulmonary rehabilitation, and symptomatic and maintenance pharmacotherapy according to severity, can significantly improve a patient’s health-related quality of life, reduce exacerbations and their consequences, and alleviate the functional, utilization, and financial burden of COPD. Redesign of primary care according to principles of the chronic care model, which is implemented in the patient-centered medical home, can shift COPD management from acute rescue to proactive maintenance. The chronic care model and patient-centered medical home combine delivery system redesign, clinical information systems, decision support, and self-management support within a practice, linked with health care organization and community resources beyond the practice. COPD care programs implementing two or more chronic care model components effectively reduce emergency room and inpatient utilization. This review guides primary care practices in improving COPD care workflows, highlighting the contributions of multidisciplinary collaborative team care, care coordination, and patient engagement. Each primary care practice can devise a COPD care workflow addressing risk awareness, spirometric diagnosis, guideline-based treatment and rehabilitation, and self-management support, to improve patient outcomes in COPD.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive yet preventable and treatable disease characterized by incompletely reversible airway obstruction, cough, dyspnea, and phlegm. COPD is often associated with tobacco smoking and/or air-borne particulate exposures (eg, workplace contaminants, biomass smoke, or urban air pollution) but may also reflect inherited α-antitrypsin deficiency and/or idiopathic causes.Citation1,Citation2 Current care patterns for COPD reflect reactive “rescue care,” in which health professionals and patients seldom interact except during episodes of acute illness,Citation3 such as exacerbations (worsening of COPD symptoms, which affect patients’ functioning and require a change in management). An exacerbation emergency is often the first presentation of previously undiagnosed but symptomatic COPD, which may progress to severe disease before patients seek care,Citation4,Citation5 especially in patients who seldom attend or have insufficient access to primary care. Because COPD exacerbations are major drivers of COPD progression,Citation6 functional deficits,Citation7 health care utilization,Citation8 and cost burden,Citation9 rescue care alone is not optimal for COPD.Citation10 Acute care for emergent COPD exacerbations is insufficient to maintain patients’ functioning or affect the disease course,Citation10 a punctuated equilibrium in which each successive exacerbation can accelerate respiratory decline.Citation6 Proactive diagnosis and management before the first exacerbation occurs can reduce exacerbation incidence and severity and improve outcomes.Citation10 Chronic care redesign, to refocus primary practice toward proactive maintenance, can improve care for COPD and other ambulatory-care-sensitive conditions (in which hospitalization rates rise as primary care becomes less accessible and/or adequate).Citation11

Proactive, multifactorial COPD care – including smoking cessation, vaccinations, physical activity, and maintenance pharmacotherapy to reduce future exacerbations – can lessen the physical, care-utilization, and financial burdens of COPD.Citation1,Citation2 Physicians can uncover unacknowledged symptoms of COPD by inquiring about patients’ reductions in activity as well as overt dyspnea.Citation12 Primary care questionnaires and other tools aid identification of candidates for spirometry.Citation13,Citation14 Spirometry can be effectively performed in primary care practices to conclusively diagnose COPD,Citation15 and is an essential tool for confirming COPD and distinguishing it from other respiratory diseases.

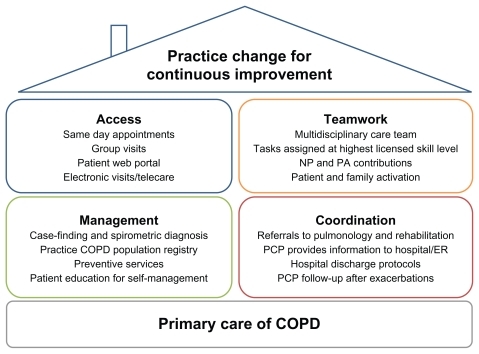

Primary care of COPD can benefit from application of Wagner’s chronic care model (CCM)Citation16 as implemented in the patient-centered medical home (PCMH).Citation17 These approaches seek to transform care delivery from a rescue orientation to a planned-care orientationCitation3 and to empower patients and families to collaborate actively with the health care team.Citation18 Core aspects of the CCM within a practice include delivery system redesign (eg, for advanced access to same-day primary care appointments), clinical information systems, decision support for clinicians (such as point-of-care guideline reminders), and support for patient self-management.Citation18 Additional aspects concern coordination with health care organizations outside the practice (eg, accountable care organizations integrating specialty and inpatient care with chronic primary care to achieve care coordination and cost savings)Citation19,Citation20 and linkage to community resources.Citation18 The medical home concept has existed since 1967, when it was developed to coordinate pediatric care for children with special needs.Citation17 More recently the PCMH has been articulated as a broad framework for transforming primary care for patients of all ages. Society signatories to the 2007 Joint Principles of the PCMHCitation17 include the American Academy of Family Practice, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians (ACP), and American Osteopathic Association;Citation17 the American Medical Association subsequently ratified the Joint Principles.Citation21 Through the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative, a multitude of other professional organizations support the PCMH; just a few examples include the American Colleges of Osteopathic Family Physicians and Osteopathic Internists, ACP, American Academies of Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants, and American Board of Internal Medicine. gives an overview of PCMH principles applied to COPD care. Additionally, in 2010 the ACP enunciated principles for the PCMH neighbor,Citation22 a conceptual framework for specialty practices collaborating with the PCMH in patient care.

Figure 1 Key aspects of the patient-centered medical home applied to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) care.

CCM implementations for COPD including at least two aspects of Wagner’s model have been shown to reduce inpatient and emergency utilization.Citation23 Successful chronic care requires both practice redesign and patient engagement. Informing and activating patients is indispensable but not sufficient. Third-party disease management programs or other interventions targeted purely to patients are attractive to payers because of perceived cost savings and to practices because of perceived economy of effort. However, chronic care programs that also transform practice organizational culture have greater impact than those requiring the patients to do all the changing.Citation24 Collaborative multidisciplinary care teams within a practice and care coordination with inpatient, emergency, and specialty services beyond primary care practice walls are particularly important for improving COPD management.

This review article aims to provide practical methods and examples for implementing proactive primary care workflows for patients with COPD, focusing particularly on the CCM principles of multidisciplinary team collaboration, care coordination, and patient activation.

Planned care for COPD: changing practice focus from rescue to maintenance

The CCM was developed to free primary care from the “tyranny of the urgent,”Citation18,Citation25 in which acute concerns crowd out chronic conditions for priority in time-limited primary care visits. Proactive maintenance of chronic disease including COPD requires protected resources: multidisciplinary care teams allowing division of labor between acute and chronic care, and scheduled well-care visits supported by previsit planning and providing dedicated chronic care time.Citation3 Additionally, since office visits represent a tiny fraction of patients’ time,Citation25 the CCM strives to activate and educate patients to take care of themselves between visits in the community they live in.

Planned COPD visits should be dedicated solely to COPD maintenance and may include individual patients or groups of patients; visits involving medication management or patient education may be conducted by a nurse or clinical pharmacist using physician-written protocols or standing orders.Citation3 Each chronic care visit should have a specific agenda (eg, spirometry and disease staging, pharmacotherapy initiation, inhaler training, patient education, establishment of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy and support, and physical activity planning), so that all aspects of COPD management are consciously targeted.

COPD maintenance in primary care should reflect current COPD guidelines.Citation1,Citation2,Citation26 Practices can create simple tools (eg, visit templates and task grids) to embody guideline essentials in daily workflow; use of electronic medical records (EMRs) linking each visit to patients’ known histories also facilitates opportunistic respiratory follow-up when patients with known or suspected COPD visit the practice for other reasons.Citation25

Guideline-based management of spirometrically diagnosed stable COPD comprises risk reduction, symptomatic and maintenance pharmacotherapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation, as well as additional interventions for severe or very severe disease (oxygen therapy, surgery, and palliative care). The Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2010Citation1 and American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) 2004 guidelinesCitation2 address management of stable COPD and exacerbations, whereas the 2011 ACP/ American College of Chest Physicians/ATS/ERS update (ACP/ACCP/ATS/ERS)Citation26 focuses on diagnosis and management of stable COPD.

Risk reduction measures appropriate throughout the course of COPD include smoking cessation and influenza vaccination for all patients and pneumonia vaccination for senior patients.Citation1,Citation2 Pharmacotherapy is generally prescribed according to COPD severity and symptoms. Short-acting bronchodilators (GOLD 2010 specifies short-acting β-adrenergic agonists) may be used for symptom relief at any stage of COPD.Citation1,Citation2 Maintenance therapy with long-acting antimuscarinic or β-adrenergic agents is recommended beginning at moderate disease (GOLD 2010),Citation1 for persistent symptoms (ATS/ERS 2004),Citation2 or at forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) < 60% predicted (ACP/ACCP/ATS/ ERS 2011).Citation26 The latter guidelines also suggest maintenance treatment in symptomatic patients with FEV1 between 60% and 80% predicted, while calling for further research in this disease stage.Citation26 Inhaled corticosteroids are not preferred as monotherapy,Citation1,Citation26 but may be added to maintenance treatment for more advanced disease and repeated exacerbations.Citation1,Citation2 ACP/ACCP/ATS/ERS 2011 suggests that clinicians may administer combination therapies to symptomatic patients with FEV1 < 60% predicted while weighing potential benefits and harms on a case-by-case basis.Citation26

GOLD 2010 includes the recently US-approved oral phosphodiesterase inhibitor roflumilast and states that, “In patients with Stage III: Severe COPD or Stage IV: Very Severe COPD and a history of exacerbations and chronic bronchitis, roflumilast reduces exacerbations treated with oral glucocorticosteroids.”Citation1

Pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended by GOLD 2010Citation1 to begin in moderate disease, by ATS 2004Citation2 for patients with respiratory symptoms and functional limitations, and by ACP/ACCP/ATS/ERS 2011Citation26 for symptomatic patients with FEV1 < 50%. ACP/ACCP/ATS/ERS 2011Citation26 further states that clinicians may consider pulmonary rehabilitation for symptomatic or exercise-limited patients with FEV1 > 50%. All three guidelines provide additional therapies for severe and very severe COPD: long-term oxygen in hypoxic severe disease, and possible surgical referral in very severe emphysematous COPD.Citation1,Citation2,Citation26

GOLD-recommended long-acting maintenance treatments include the long-acting β-adrenergic bronchodilators salmeterol or formoterol, their corticosteroid combinations salmeterol/fluticasone or formoterol/budesonide, and the long-acting antimuscarinic agent tiotropium. Two of these maintenance regimens, tiotropium and salmeterol/ fluticasone, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to reduce exacerbations of COPD. Tiotropium is approved “for the once-daily, maintenance treatment of bronchospasm associated with COPD”Citation27 and “to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients,”Citation27 and salmeterol/fluticasone is approved “for the twice-daily maintenance treatment of airflow obstruction in patients with COPD”Citation28 and “to reduce exacerbations of COPD in patients with a history of exacerbations.”Citation28 Indacaterol, a long-acting β-adrenergic agonist, received FDA approval in 2011 “for the long term, once-daily maintenance bronchodilator treatment of airflow obstruction in patients with COPD, including chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema.”Citation29

Chronic care toolbox for COPD

Tools for proactive primary care of COPD include a time-line of care tasks for the first year or more after diagnosis, task grids for division of labor among a multidisciplinary care team, checklists for assuring that the right care takes place at the right time, metrics for tracking improvement in COPD care processes and outcomes, and an intrapractice COPD patient registry that can be readily developed from meaningful EMR use.

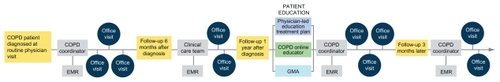

A basic model of the COPD patient journey used in the author’s work with the educational Group Practice Forum is shown in . Practices can customize a workflow to fit their available resources and patients’ needs; core features include spirometric diagnosis when a patient presents with suspected COPD, a physician-directed care plan, a designated COPD coordinator who handles patient intake, follow-up, and COPD registry use by means of the EMR, and provision of comprehensive in-person and online patient education within the first year after diagnosis.

Figure 2 Sample patient journey for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Task assignment across the care team will look different depending on practice size and resources. Even a solo practice with one physician and one nurse benefits from regular planned shared reflection and conscious division of labor.Citation30 A large group practice will have available many types of professionals, eg, physicians, medical assistants, registered nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, registered respiratory therapists and physical therapists, dieticians, and/ or clinical pharmacists. Successful collaborative care teams assign tasks based on actual skill sets and ensure that every team member works at the highest skill level permitted by licensing.

Nursing professionals (from medical assistants through licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and nurse practitioners) have many potential touch points with patients, such as autonomous office visits or home visits not requiring a physician, electronic visits, and/or group COPD education sessions. An ideal task apportionment amongst the COPD team distributes tasks throughout the care team rather than concentrating them upon physicians. Additionally, nurses can provide needed follow-up to patients between visits, answering questions, teaching and monitoring inhaler technique, and assisting adherence.

A COPD coordinator (the author’s practice places a registered nurse in this role) can handle new COPD patient intake, treatment planning under long-range physician guidance, EMR use, and health literacy assessment and follow-up comprising self-management teaching, medication adherence assessment, and depression screening. Assignment of respiratory care specialists and specially trained registered respiratory therapists or registered nurses to management of COPD at Baylor University’s lung program multiplied rates of spirometry use (26% to 100% in internal medicine and 4% to 100% in geriatrics; P < 0.05 for both) and documented inhaler training (13% to 90% in internal medicine, P < 0.05).Citation31 Staff members who themselves are coping with asthma or COPD (or have affected relatives) make excellent peer-educators and champions for inhaler technique.

A practice COPD registry facilitates planned care, longitudinal follow-up, and improvement at the level of the practice’s COPD population. Registry contents can be developed by using EMR capabilities to identify all patients with diagnosed or suspected COPD and to track COPD-care-related metrics, such as receipt of spirometry, lung function parameters, guideline-appropriate treatment, physical activity levels, exacerbation incidence/frequency, and resulting care utilization. Simpler registries are more sustainable than complex ones, especially at first. Patients may be allowed to access their own registry information via a secure Web portal to facilitate self-management; patients may even be allowed to enter patient-reported information, eg, on exacerbation triggers and incidence, as-needed inhaler usage levels, and physical activities. Web views for care team members within the practice can be configured to allow viewing and management of benchmark indicators for the entire COPD patient population.

Metrics allow the practice to track important processes and outcomes of COPD care and provide continuous feedback that permits continuous improvement. Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles can be as simple as a solo physician and practice nurse discussing a process improvement, trying it immediately, and discussing the results a week later.Citation30 Plan-Do-Study-Act is useful for incremental process improvements;Citation32 however, practice-wide transformation to PCMH methodology often entails multiple interdependent changes exceeding the scope of Plan-Do-Study-Act.Citation33 Within-practice metrics facilitate process and outcome improvement; externally visible metrics often inform compensation. Currently, COPD care has fewer publicly reportable metrics than, for example, diabetes care, placing COPD at a disadvantage in pay-for-performance programs.Citation34 Ideally, metrics should be selected on the basis of evidence for their contribution to clinical improvement. The diabetes experience indicates that ease of measurement does not necessarily predict impact on patient outcomes.Citation35 Possible metrics for COPD care include levels of utilization of the COPD-Population Screener™Citation13 or other risk-awareness questionnaires, spirometry utilization, treatment guideline adherence (eg, maintenance inhaler treatment for patients at or beyond moderate COPD),Citation1 and primary care follow-up rates promptly after an exacerbation-related emergency room (ER) or inpatient episode.Citation36 Presentation of metrics in chronological order with effective graphics allows immediate visualization of trends and areas needing improvement. The author’s practice uses a COPD dashboard visualizing patients’ individual metrics for the patient-accessible Web portal and the practice’s COPD population metrics for the in-clinic professional view. Whether metrics measure care processes or the resulting outcomes, all should contribute to the ultimate goal of improving outcomes for patients with COPD (eg, increased activity levels and medication adherence, reduced exacerbation rates, reduced ER and hospital visits, and improved follow-up during transitions to and from hospital).

CCM and PCMH methods invite practices to reconceptualize their workflow to make optimal use of the unique combination of skills in each practice’s multidisciplinary care team. This team comprises not only the practice’s various professionals but also enlists patients themselves.

From passive recipients to active participants: transforming patients’ behavior

Patient training for self-management is an essential part of chronic care, and particularly of COPD management. However, purely didactic prePCMH models of patient education need to give way to those focused on practical skills and behavioral change. Disease knowledge is an overused outcome of chronic care or self-management programs for COPD. Published COPD chronic care programs with knowledge as their main measured outcome are more numerous but less effective than comprehensive self-management interventions addressing education and health literacy, motivation, and behavioral changes.Citation23 Engagement of patients and families to take an active role in managing their health is central to the CCM.Citation16

Self-management support, including COPD exacerbation action plans and proactive professional follow-up by telephone as well as education, has been shown to reduce health care utilization requirements. Among 743 US veterans with severe COPD randomized to receive either usual care or a self-management intervention comprising 1.5 hours of initial education, a plan for self-care of exacerbations, and a monthly call from a case manager, self-management support significantly reduced COPD-related and other cardiopulmonary hospitalizations, any-cause hospitalizations, and any-cause ER visits versus usual care.Citation37 A similar program with more extensive education (8 weekly professional education visits, exacerbation action plan, and telephone follow-up) in a Canadian randomized trial in severe COPD reduced hospitalizations by 39.8%, ER visits by 41.0%, and unscheduled physician visits by 57.1% versus control.Citation38 Proactive integrated care including 3 months’ home telemonitoring of daily spirometry, pulse oximetry, pedometry, and symptoms identified unreported exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPD and significantly improved health-related quality of life versus usual care.Citation39

The concept of remote COPD patient support has been extended into a variety of schemes for telehealthcare, in which electronic interactions between patients and care team members allow for various combinations of education, adherence improvement, patient data collection, electronic care visits, early detection and management of exacerbations, reduction of unscheduled office and ER visits, or rehospitalization prevention.Citation40 Telehealthcare for COPD was shown in a recent Cochrane Database reviewCitation40 to significantly reduce ER visits and hospitalizations versus usual care. A limitation of the review was that telehealthcare was frequently embedded in more complex integrated care interventions, thus most reviewed studies did not test the effect of telehealthcare in isolation.

Pulmonary rehabilitation provides aerobic exercise training, psychosocial interaction, and education to patients with COPD. It is recommended to begin with moderate disease (GOLD),Citation1 symptomatic disease (ATS/ERS),Citation2 or at FEV1 < 50% (though suggested for symptomatic, exercise-limited patients of FEV1 > 50% predicted; ACP/ACCP/ATS/ ERS 2011),Citation26 but pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve respiratory and/or physical functioning in any stage of COPD.Citation41 Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to improve patient-reported dyspnea similarly to in-center pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with moderate to severe COPD.Citation42 Several long-acting inhaled maintenance therapies, eg, tiotropium,Citation43 salmeterol,Citation44 formoterol,Citation45 budesonide/formoterol,Citation46 salmeterol/fluticasone,Citation47 or tiotropium plus salmeterol/fluticasone,Citation48 have been shown to improve patients’ ability to exercise, and combining maintenance therapy with formal pulmonary rehabilitation has improved exercise outcomes beyond those obtained with pulmonary rehabilitation alone.Citation43,Citation49

Beyond the specific interventions of patient education and pulmonary rehabilitation, clinicians face the challenge of enlisting patients to collaborate actively in managing their COPD. Where the concept of compliance focuses narrowly on patients following doctors’ orders to take medications, concordance engages patients in their daily lives and environments – where they live, work, and play – to craft a comprehensive and sustainable lung-friendly lifestyle.Citation50 Establishing concordance involves engaging patients where they currently are on the arc of acceptance of their disease. In dealing with a new COPD diagnosis, patients often experience stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, depression – on their way to acceptance, and their decisions about smoking cessation and other self-care may be complicated by this process. Anxiety and reluctance to acknowledge COPD-related limitations are related to nonadherence with therapy and poor respiratory and functional coping.Citation51 Depression adversely affects coping with COPD including therapy adherence; training in problem-solving skills may improve adherence in elderly COPD patients.Citation52 Smokers may often admit the risks of smoking in general but tacitly believe that they themselves are not personally susceptible to lung damage. Confrontational counseling for smoking cessation, communicating spirometric evidence of airflow limitation, decreased participants’ denial and increased both their perception of risk and their confidence in their ability to quit (self-efficacy), thus improving cessation rates versus conventional health promotion.Citation53 Motivational interviewing is an effective tool for lifestyle change; it has been shown to help in smoking cessationCitation54 and concurrent depression management,Citation55 to enhance self-management of COPD,Citation56 and to improve adherence to medication.Citation57 The most powerful self-management programs incorporate robust interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and treatment of comorbid depression.Citation23

Adherence and persistence with medication are crucial to therapeutic effectiveness. The “brown bag” technique, in which a patient brings all their medications to a primary care appointment and describes how the medications are taken, allows a care team member (eg, clinical pharmacist) to monitor adherence and reconcile potential interactions or errors at every visit.Citation58 Inhaler technique is important in achieving COPD treatment effectiveness; yet inhaler misuse remains prevalent even among experienced users of respiratory medications. Citation59 Poor maintenance inhaler technique is associated with increased inpatient and emergency care utilization and greater need for systemic steroids and antibiotics. Citation59 Practices need to assign inhaler technique teaching to a specific champion and build it consistently into their COPD workflow,Citation60 and patients need to build medication use into their own unique daily lives. Routinized medication taking in tandem with a consistent daily activity (eg, brushing of teeth) assists adherence.Citation61

Care coordination: smoothing transitions and maintaining continuity

In addition to other aspects of the CCM, care coordination and transition management beyond the confines of the primary practice are crucial to successful chronic care for COPD. Providing all professionals (within the practice and in other referral or inpatient/ER settings) the same up-to-date information about each patient fosters continuity of care and reduces misunderstandings and rework. Referrals (eg, to pulmonologists, pulmonary function labs, and other specialists such as cardiologists) are increasingly needed as COPD advances; in a PCMH, processes must be in place for arranging referrals, receiving specialists’ reports, and following up with patients.Citation62 Availability and efficiency of referrals does not necessarily correlate with the size or connectivity of a care organization outside the primary practice, but does depend critically on all appropriate employees having access to the same accurate information about clinicians’ availability and patients’ needs. Integrated and accountable care organizations form patient-centered medical villages for the PCMH, in which specialty expertise is appropriately accessed by primary physician and patient while supply-sensitive overuse is avoided.Citation19,Citation20 Pulmonary rehabilitation may be practice-based, accountable care organization-based, or referred externally.

Specialist practices that collaborate with referring PCMH primary practices may become PCMH neighbors with processes ensuring appropriate, timely consultations and referrals, sharing information bidirectionally with a PCMH, and determining responsibility for each aspect of collaborative patient care.Citation22 Interactions between the specialty clinic and PCMH will vary in duration, intensity, and division of labor. Types of interactions range from the preconsultation exchange, eg, “curbside consult” for the primary care physician to ask questions informally, through a formal time-limited consultation to an ongoing shared management arrangement. In certain severe life-limiting diseases the specialist may take on responsibility for principal care. Collaboration between a PCMH and specialist neighbor can be facilitated by a care coordination agreement that specifies contents of a patient transition record, defines expectations of information sharing, sets accountability and which practice does what care tasks, and clarifies transition processes for hospitalization and discharge.Citation22

Attention to transitions to and from the ER or hospital can improve care for patients who experience emergent exacerbations of COPD. Provision of information from primary care to the ER or hospital and proper information sharing within inpatient venues can avoid redundant questioning of patients or failure to act on important health problems.Citation32 In turn, hospitals and ERs should alert primary care physicians when patients with known chronic respiratory conditions are admitted.Citation32 An 18-month program of guided primary care for multimorbid elderly patients led by specially trained registered nursesCitation63 achieved significant improvements in coordination of care by making the guided-care nurse responsible for transition arrangements. Hospitalization for an exacerbation may be an opportunity to begin guideline-appropriate maintenance treatment.Citation10,Citation64 Conversely, sometimes hospitalization may interrupt an existing maintenance regimen for COPD. Careful medication reconciliation, and preserving or resuming regimens appropriately, is important when patients enter and leave the hospital.Citation32 PCMH methodology can improve primary care follow-up after a COPD-related ER visit or inpatient stay, which in turn can improve postexacerbation outcomes for patients. A PCMH demonstration project significantly improved the proportion of patients who received follow-up communications from their primary care physician within 3 days after an ER visit.Citation36 Integrated postdischarge care after hospitalization for an exacerbation, consisting of an individualized plan shared with the primary care team and provision of telephone patient support from a nurse case manager, improved patients’ recognition and self-care of exacerbations and their medication adherence and inhaler technique.Citation65

Conclusion

Recent literature indicates that COPD chronic care programs implementing two or more components of the original CCM effectively reduce ER and inpatient utilization. Advanced primary care access scheduling and robust self-management support were the CCM components showing most evidence for benefit in COPD according to a 2007 systematic review.Citation23 Multidisciplinary collaborative team care will be implemented differently in practices of different sizes and skill sets; each primary care practice can devise a team COPD care workflow that implements essential tasks of risk awareness, spirometric diagnosis, guideline-based treatment and rehabilitation, and equipping patients for self-management. Chronic care for COPD must reach beyond the primary care practice into patients’ lives in the community on the one hand, and into practices’ linkages with specialty, ER, and inpatient care on the other. Continuity and communication in care transitions are essential, especially when patients are treated for exacerbations in the hospital or ER, to maintain ongoing care regimens and respond to changes in patients’ respiratory and physical prognosis. Primary care practices that expend the effort to transform their approach to chronic diseases, including COPD, by using CCM and PCMH concepts, reduce utilization burdens and physical/ psychosocial sequelae more effectively than the default reactive primary care approach. Patient-centered chronic care for COPD promises to improve health-related quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

This review article was developed from presentations and discussions at the Overcoming Barriers to COPD Identification and Management task force meeting in New York, NY, March 22–23, 2009. This meeting, the author’s participation, and manuscript preparation were supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc (BIPI) and Pfizer. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Kim Coleman Healy of Envision Scientific Solutions, which was contracted by BIPI for these services. The author meets criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, was fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and was involved at all stages of review article development. The author received no compensation for manuscript development. The article reflects the concepts of the author and is his sole responsibility. It was not reviewed by BIPI and Pfizer except to ensure medical and safety accuracy.

Disclosure

Dr Fromer is the Executive Medical Director of The Group Practice Forum and is on the board of TransforMED; he has received honoraria for speakers’ bureau participation from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Pfizer.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD122010 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed July 25, 2011

- American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory SocietyStandards for the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD2004 Available from: http://www.thoracic.org/clinical/copd-guidelines/Accessed October 25, 2011

- BodenheimerTPlanned visits to help patients self-manage chronic conditionsAm Fam Physician20057281454145616273815

- BastinAJStarlingLAhmedRHigh prevalence of undiagnosed and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at first hospital admission with acute exacerbationChron Respir Dis201072919720299538

- ZoiaMCCorsicoAGBeccariaMExacerbations as a starting point of pro-active chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managementRespir Med200599121568157515890509

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTABhowmikAWedzichaJARelationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2002571084785212324669

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCPaulEABestallJCJeffriesDJWedzichaJAEffect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19981575 Pt 1141814229603117

- McGhanRRadcliffTFishRSutherlandERWelshCMakeBPredictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPDChest200713261748175517890477

- HalpernMTStanfordRHBorkerRThe burden of COPD in the USA: results from the Confronting COPD surveyRespir Med200397Suppl CS818912647946

- AnzuetoAPrimary care management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to reduce exacerbations and their consequencesAm J Med Sci2010340430931820625276

- BindmanABChattopadhyayAAuerbackGMInterruptions in Medicaid coverage and risk for hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditionsAnn Intern Med20081491285486019075204

- ZuWallackRHow are you doing? What are you doing? Differing perspectives in the assessment of individuals with COPDCOPD20074329329717729076

- MartinezFJRaczekAESeiferFDDevelopment and initial validation of a self-scored COPD Population Screener Questionnaire (COPD-PS)COPD200852859518415807

- YawnBPMapelDWManninoDMMartinezFJDalalAAPerformance of a brief, self-administered questionnaire (Lung Function Questionnaire) to identify patients at risk of airflow obstruction as potential candidates for spirometry: scoring and cut pointAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179A1476

- YawnBPEnrightPLLemanskeRFJrSpirometry can be done in family physicians’ offices and alters clinical decisions in management of asthma and COPDChest200713241162116817550939

- WagnerEHChronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness?Eff Clin Pract1998112410345255

- American Academy of Family PhysiciansJoint principles of the patient-centered medical homeDel Med J2008801212218284087

- BodenheimerTWagnerEHGrumbachKImproving primary care for patients with chronic illnessJAMA2002288141775177912365965

- RittenhouseDRShortellSMFisherESPrimary care and accountable care – two essential elements of delivery-system reformN Engl J Med2009361242301230319864649

- FisherESMcClellanMBBertkoJFostering accountable health care: moving forward in MedicareHealth Aff (Millwood)2009282w219w23119174383

- BeinBAMA delegates adopt AAFP’s joint principles of patient-centered medical homeAnn Fam Med2009718687

- American College of PhysiciansThe Patient-Centered Medical Home Neighbor. The Interface of the Patient-Centered Medical Home with Specialty/ Subspecialty Practices. Policy paperPhiladelphia, PAAmerican College of Physicians2010

- AdamsSGSmithPKAllanPFAnzuetoAPughJACornellJESystematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and managementArch Intern Med2007167655156117389286

- ColemanKMattkeSPerraultPJWagnerEHUntangling practice redesign from disease management: how do we best care for the chronically illAnnu Rev Public Health20093038540818925872

- MooreLGEscaping the tyranny of the urgent by delivering planned careFam Pract Manag2006135374016736903

- QaseemAWiltTJWeinbergerSEDiagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory SocietyAnn Intern Med2011155317919121810710

- Boehringer IngelheimSpiriva® HandiHaler® prescribing information62010 Available from: http://bidocs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/BIWebAccess/ViewServlet.ser?docBase=renetnt&folderPath=/Prescribing+Information/PIs/Spiriva/Spiriva.pdfAccessed February 17, 2011

- GlaxoSmithKlineAdvair Diskus prescribing information62010 Available from: http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_advair.pdfAccessed February 17, 2011

- NovartisArcapta™ Neohaler™ prescribing information72011 Available from: http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/arcapta.pdfAccessed August 25, 2011

- MooreLGCreating a high-performing clinical teamFam Pract Manag2006133384016568595

- HartMKMillardMWApproaches to chronic disease management for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: strategies through the continuum of careProc (Bayl Univ Med Cent)201023322322920671816

- DoddsSChamberlainCWilliamsonGRModernising chronic obstructive pulmonary disease admissions to improve patient care: local outcomes from implementing the Ideal Design of Emergency Access projectAccid Emerg Nurs200614314114716762552

- NuttingPAMillerWLCrabtreeBFJaenCRStewartEEStangeKCInitial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical homeAnn Fam Med20097325426019433844

- HeffnerJEMularskiRACalverleyPMCOPD performance measures: missing opportunities for improving careChest201013751181118920348199

- HoferTPZemencukJKHaywardRAWhen there is too much to do: how practicing physicians prioritize among recommended interventionsJ Gen Intern Med200419664665315209603

- ReidRJFishmanPAYuOPatient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluationAm J Manag Care2009159e71e8719728768

- RiceKLDewanNBloomfieldHEDisease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182789089620075385

- BourbeauJJulienMMaltaisFReduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management interventionArch Intern Med2003163558559112622605

- KoffPBJonesRHCashmanJMVoelkelNFVandivierRWProactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPDEur Respir J20093351031103819129289

- McLeanSNurmatovULiuJLPagliariCCarJSheikhATelehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20117CD00771821735417

- TakigawaNTadaASodaRComprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation according to severity of COPDRespir Med2007101232633216824743

- MaltaisFBourbeauJShapiroSEffects of home-based pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med20081491286987819075206

- CasaburiRKukafkaDCooperCBWitekTJJrKestenSImprovement in exercise tolerance with the combination of tiotropium and pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPDChest2005127380981715764761

- O’DonnellDEVoducNFitzpatrickMWebbKAEffect of salmeterol on the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J2004241869415293609

- NederJAFuldJPOverendTEffects of formoterol on exercise tolerance in severely disabled patients with COPDRespir Med2007101102056206417658249

- WorthHForsterKErikssonGNihlenUPetersonSMagnussenHBudesonide added to formoterol contributes to improved exercise tolerance in patients with COPDRespir Med2010104101450145920692140

- O’DonnellDESciurbaFCelliBEffect of fluticasone propionate/ salmeterol on lung hyperinflation and exercise endurance in COPDChest2006130364765616963658

- PasquaFBiscioneGCrignaGAucielloLCazzolaMCombining triple therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with advanced COPD: a pilot studyRespir Med2010104341241719892540

- KestenSCasaburiRKukafkaDCooperCBImprovement in self-reported exercise participation with the combination of tiotropium and rehabilitative exercise training in COPD patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083112713618488436

- WeissMBrittenNWhat is concordance?Pharm J20032717270493

- PostLCollinsCThe poorly coping COPD patient: a psychotherapeutic perspectiveInt J Psychiatry Med19811121731827263134

- AlexopoulosGSRauePJSireyJAAreanPADeveloping an intervention for depressed, chronically medically ill elders: a model from COPDInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200823544745317932995

- KotzDHuibersMJWestRJWesselingGvan SchayckOCWhat mediates the effect of confrontational counselling on smoking cessation in smokers with COPD?Patient Educ Couns2009761162419150590

- ToljamoTKaukonenMNieminenPKinnulaVLEarly detection of COPD combined with individualized counselling for smoking cessation: a two-year prospective studyScand J Prim Health Care2010281414620331388

- WilhelmKArnoldKNivenHRichmondRGrey lungs and blue moods: smoking cessation in the context of lifetime depression historyAust N Z J Psychiatry20043811–1289690515555023

- RobinsonACourtney-PrattHLeaETransforming clinical practice amongst community nurses: mentoring for COPD patient self-managementJ Clin Nurs20081737037918205693

- KlokTSulkersEJKapteinAADuivermanEJBrandPLAdherence in the case of chronic diseases: patient-centred approach is neededNed Tijdschr Geneeskd2009153A420 Dutch19900323

- NathanAGoodyerLLovejoyARashidA“Brown bag” medication reviews as a means of optimizing patients’ use of medication and of identifying potential clinical problemsFam Pract199916327828210439982

- MelaniASBonaviaMCilentiVInhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease controlRespir Med2011105693093821367593

- MelaniASInhalatory therapy training: a priority challenge for the physicianActa Biomed200778323324518330086

- GeorgeJKongDCStewartKAdherence to disease management programs in patients with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20072325326218229563

- National Committee for Quality AssuranceStandards and Guidelines for Physician Practice Connections®-Patient-Centered Medical Home (PPC-PCMH™)Washington, DCNational Committee for Quality Assurance2008

- BoydCMReiderLFreyKThe effects of guided care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trialJ Gen Intern Med201025323524220033622

- DrescherGSCarnathanBJImusSColiceGLIncorporating tiotropium into a respiratory therapist-directed bronchodilator protocol for managing in-patients with COPD exacerbations decreases bronchodilator costsRespir Care200853121678168419025702

- Garcia-AymerichJHernandezCAlonsoAEffects of an integrated care intervention on risk factors of COPD readmissionRespir Med200710171462146917339106