Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most prevalent and debilitating diseases in adults worldwide and is associated with a deleterious effect on the quality of life of affected patients. Although it remains one of the leading causes of global mortality, the prognosis seems to have improved in recent years. Even so, the number of patients with COPD and multiple comorbidities has risen, hindering their management and highlighting the need for futures changes in the model of care. Together with standard medical treatment and therapy adherence – essential to optimizing disease control – several nonpharmacological therapies have proven useful in the management of these patients, improving their health-related quality of life (HRQoL) regardless of lung function parameters. Among these are improved diagnosis and treatment of comorbidities, prevention of COPD exacerbations, and greater attention to physical disability related to hospitalization. Pulmonary rehabilitation reduces symptoms, optimizes functional status, improves activity and daily function, and restores the highest level of independent physical function in these patients, thereby improving HRQoL even more than pharmacological treatment. Greater physical activity is significantly correlated with improvement of dyspnea, HRQoL, and mobility, along with a decrease in the loss of lung function. Nutritional support in malnourished COPD patients improves exercise capacity, while smoking cessation slows disease progression and increases HRQoL. Other treatments such as psychological and behavioral therapies have proven useful in the treatment of depression and anxiety, both of which are frequent in these patients. More recently, telehealthcare has been associated with improved quality of life and a reduction in exacerbations in some patients. A more multidisciplinary approach and individualization of interventions will be essential in the near future.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most prevalent and debilitating diseases in adults worldwide. According to the estimation of the World Health Organization, 210 million people have COPD and 3 million people died of COPD in 2005.Citation1 COPD is associated with high morbidity and mortality and with a significant deterioration in the quality of life (QoL), especially, but not only, in the advanced stages of the disease.

Fortunately, several recent studies suggest a decrease in the global impact of the disease. The latest estimations of the Global Burden of Disease Study show that COPD was, in 2010, the third-leading cause of mortality worldwide and ninth in the combination of years of life lost or lived with disability (disability-adjusted life years, or DALYs). These data represent an improvement over previous predictions made by the same group and indicate that global mortality and DALYs for COPD in all ages have decreased between 1990 and 2010 by 6.4% and 2.0%, respectively (or measured in age-standardized death rates, a reduction in mortality of 43% and in DALYs of 25%).Citation2,Citation3 Several other studies performed with large databases or cohorts also suggest that the prognosis of patients with COPD has improved in the last decade.Citation4–Citation8 Because COPD, like many other medical conditions, is not presently curable, the most likely future scenario is that most COPD patients will live progressively longer and thus will suffer more often from concomitant chronic diseases.Citation9 In this sense, several studies performed in patients hospitalized for COPD have reported an increase in the percentage of people older than 85 years of age, along with a greater prevalence of comorbidities and a decrease in physical performance.Citation7,Citation9

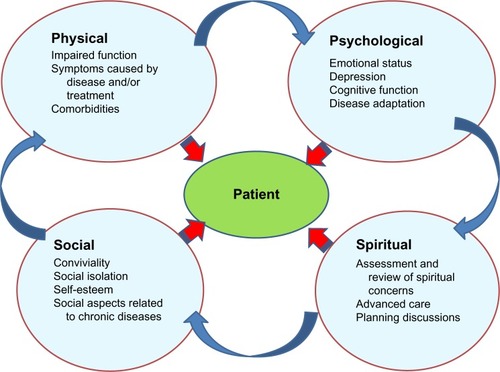

This should lead physicians and other health players to expand the traditional assessment of chronic diseases (based on terms of diagnosis and morbidity and mortality rates) to include other priorities, such as preventing disability, preserving quality of life, and integrating patient perception and adaptation into the limitations caused by the disease ().Citation10,Citation11

In the present narrative review, we will highlight the recent literature in order to evaluate nonpharmacological therapies focused on preserving the QoL of patients with COPD and the desirable changes in the care model for management of patients with COPD and several concomitant chronic diseases, overcoming the single-disease focus that pervades medicine.Citation12

Search strategies

We performed multiple searches in PubMed and the Cochrane Library about the different nonpharmacological measures that have been related to QoL in patients with COPD. We also used various search strategies that combined the keyword “COPD” with other terms, such as “comorbidity”, “depression”, “pulmonary rehabilitation”, “disability”, and “telehealthcare”, among others. We selected the most relevant and recent articles, prioritizing systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Quality of life and health-related quality of life

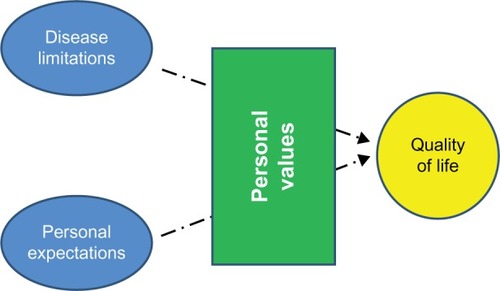

In medicine we often use the terms QoL and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) as synonyms, when in fact they are two different concepts. QoL is a totally subjective and individual notion based on personal perception, culture, and values.Citation13 By contrast, HRQoL is defined as the extent to which one’s usual or expected physical, emotional, and social well-being are affected by a medical condition or its treatment, and this can be measured with questionnaires that provide a standardized method for quantifying the impact of disease and enable assessment of the changes produced by the different interventions and disease progression.Citation14 Conceptually, HRQoL can be defined as the gap between the subject’s desires and the limitations caused by the disease; it thus can be improved by decreasing the disease limitations or with concomitant adaptation on the patient’s part ().Citation14 Of note, HRQoL should be distinguished from the concept of “functional capacity,” which is only one of its components.

Generic questionnaires allow comparison of HRQoL among different diseases and may be more useful in patients with COPD and multimorbidity. In contrast, disease-specific questionnaires are more useful in assessing responsiveness and clinical changes in the evolution of COPD and the impact of interventions (). Both methods have strengths and weaknesses and perhaps they are complementary.Citation15 Unfortunately, the use of COPD-specific questionnaires has been complex and time-consuming, limiting their utility in clinical practice. This difficulty has been remedied by the recently validated COPD Assessment Test (CAT). CAT has shown an excellent correlation with the Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and good sensitivity in detecting changes in the disease, such as exacerbations and improvement with rehabilitation.Citation16–Citation18 CAT is included in the new Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease normative alternatively to dyspnea, measured with the modified Medical Research Council scale, to assess symptom severity in the combined scale. However, to our knowledge, CAT has not been validated for mortality, and the cutoffs used (ten) were selected arbitrarily.Citation19,Citation20

Table 1 Examples of several HRQoL questionnaires in COPD

HRQoL questionnaires overcome the misconception that only lung-function values are trustworthy to evaluate the impact, prognosis, and evolution of COPD. It is well known that spirometric values are only moderately related to HRQoL, whereas dyspnea, depression, exacerbations, comorbidities, anxiety, and exercise tolerance show a more consistent association. Results for age and gender are controversial.Citation21

Comorbidity and multimorbidity

Adults with multiple chronic conditions are the main users of health care services and account for more than two thirds of health care spending. These patients had lower physical function – greater fragility and risk of disability – and a decrease in HRQoL even after adjustment for confounding variables such as age, sex, education, and perceived social support.Citation22–Citation24

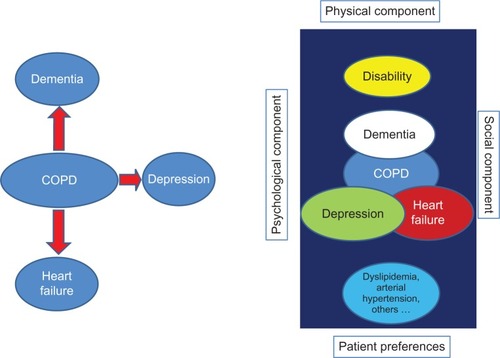

The importance of comorbidities in COPD patients and their prognostic implications have been increasingly recognized in the last decade.Citation10,Citation25,Citation26 Heart disease, hypertension, musculoskeletal disorders, and diabetes, among many other diseases, are common in COPD patients, and several epidemiological studies have shown that lung function impairment is associated with an increased risk of comorbid diseases.Citation27,Citation28 In fact, many patients with COPD have multiple concurrent comorbidities, and hence the term “multimorbidity” would be more accurate. Although multimorbidity is sometimes used interchangeably with comorbidity and pluripathology, multimorbidity implies a different concept. Comorbidity technically indicates a condition or conditions that coexist in the context of a principal disease, in our case COPD, whereas multimorbidity refers to co-occurrence of two or more chronic medical conditions that may or may not directly interact with each other within the same individual ().Citation29 The complexity of managing several chronic diseases simultaneously in the same patient requires changes in health care delivery.Citation30

Figure 3 Differences in evaluation between comorbidity and multimorbidity.

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In a recent study performed in Scotland, multimorbidity was present in 23% of the 1.75 million people included in a database from >300 medical practices. In this study, only 18% of patients had COPD as an isolated disease, whereas almost half had three or more concomitant disorders.Citation31 Similarly, in a cohort study conducted in patients with moderate or severe COPD (mean forced expiratory volume in 1 second of 51%), 62% of patients had three or more comorbidities and only 2% had COPD exclusively. This is the reason why some authors consider COPD to be just one component – and not necessarily the most important one – of the multimorbidity complex in many patients.Citation10,Citation32 Several reports have highlighted the relationship between comorbidities and an impairment of HRQoL in COPD. Two studies performed with a generic questionnaire (short-form health survey [SF-36]) showed that the combination of cardiac and respiratory disorders had a negative synergistic effect on HRQoL and that COPD patients with comorbidity had impaired scores in all domains when compared with COPD patients without comorbidity.Citation33,Citation34 Other publications also showed significant relationships between comorbidity and disability and poorer scores in the SGRQ and an inverse relationship between depression, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease and HRQoL measured with SGRQ.Citation35,Citation36

Unfortunately, the information about how to organize continuous care of these patients is limited.Citation37,Citation38 Expert consensus suggests avoiding fragmentation of care with multiple specialists involved, each attending his or her own pathology. From the perspective of the health service, treatment of diseases in isolation is inefficient, leading to duplication of care. For patients, repeat requests to attend different clinics for each chronic disease are inconvenient and confusing.Citation12 It is necessary to identify which clinician should have the primary responsibility for helping patients make decisions and to prioritize a multidisciplinary approach in collaboration with nurses, social workers, and physiotherapists, among others. When COPD is the most important patient health problem, a respiratory specialist may be the optimal primary decision maker, although these specialists should be trained in the management of the most frequent comorbidities. In other patients, oversight by a generalist, in conjunction with targeted assistance from specialists with expertise and experience in caring for complex patients with multiple chronic conditions, may be the best way to supervise the care team, as this requires integrating across all conditions within the context of each patient’s health goals and priorities. For these patients, in addition to providing the best treatment possible for their diseases, it is essential to optimize their physical function, ascertaining patient-important outcomes and avoiding inappropriate, nonbeneficial care.Citation22 Of note, these patients are usually excluded in clinical trials, so that the scientific evidence about interventions is in many cases scanty. However, many of the interventions that we will discuss below can be particularly useful in this subgroup of patients: pulmonary rehabilitation remains useful, although the improvement in exercise tolerance and QoL may be smaller in patients with musculoskeletal disorders or disability outcomes.Citation39 Physical therapies have proved beneficial even in frail, institutionalized older patients.Citation40,Citation41

Nonpharmacological treatments that improve the HRQoL in COPD

Exacerbation prevention

Exacerbations of COPD are related to an increase in short-term and long-term mortality, decline in lung function, and worsening of HRQoL. Furthermore, it is one of the events most feared by patients, so prevention is a cornerstone in the management of the disease.Citation19,Citation26,Citation42,Citation43

Diverse pharmacological therapies have proved useful in reducing the number of exacerbations and hospital admissions.Citation44 Additionally, other interventions, such as patient education for self-management, hospital at home for selected patients, discharge planning from hospital to home, and exercise prescription during hospital stay have demonstrated benefits in patients hospitalized for COPD.Citation45–Citation49 Pulmonary rehabilitation in stable patients showed a reduction in admissions for related respiratory illness, alongside a 50% reduction in the length of stay whenever hospitalization was required and a reduction in the number of exacerbations.Citation50,Citation51 Different strategies for disease management have shown a 40% reduction in COPD hospitalizations and a similar reduction in consultations at the emergency department, although not all studies have shown similar results, probably because of differences between programs.Citation52–Citation54 A Cochrane review concluded that pulmonary rehabilitation initiated during hospitalization for COPD exacerbation or shortly after discharge significantly reduced the likelihood of rehospitalization (odds ratio = 0.22; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.08–0.58), with a number needed to treat of 4 (95% CI = 3–8) and a reduction in mortality (odds ratio = 0.28; 95% CI = 0.10–0.84) with a number needed to treat of 6 (95% CI = 5–30). The group in the rehabilitation program also improved in HRQoL (measured with the fatigue and dyspnea domains of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire) and in the total scale and the activity and impact subscales of the SGRQ, although not in the symptoms.Citation55 These results were replicated in other meta-analyses, with a moderate quality of evidence and strong recommendation in favor of the intervention.Citation56,Citation57

Prevention of disability

One of the main goals in managing patients with severe COPD is to prevent adverse events related to exacerbations and hospitalizations, especially the loss of functional capacity and subsequent physical dependence in basic and instrumental activities of daily living.Citation58 New onset of disability as part of hospitalization is common; at least 30% of patients older than 70 years of age and hospitalized for a medical illness are discharged with a new disability related to activities of daily living.Citation59 Post-hospital disability has a major effect on the QoL and independence of chronic patients and on health-related expenditures, in what some authors recently termed “post-hospital syndrome.”Citation60 During hospitalization, most patients spend the majority of time in bed and nutritional status often deteriorates, accelerating muscle wasting.Citation61 In COPD, disability is related to lower levels of well-being and health status, increased levels of distress, depression, and a more pronounced illness perception.Citation62 Hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD causes marked inactivity and a loss of muscle strength, reaching an average of 5% in quadriceps, that is not fully recovered after 90 days.Citation63 Early mobilization and early rehabilitation may reduce the incidence of hospitalization-associated disability.Citation22,Citation61,Citation64 Particular attention should be focused on avoiding hospital processes that are not essential and that can impair functional recovery – ie, prolonged bed rest, inadequate nutritional support, overly restrictive diets, overuse of monitors, urinary catheters, and intravenous lines that tether patients, and the use of sedating medications – as all may contribute to loss of physical function.

Management of depression and anxiety

Depression is common in COPD patients, with an estimated prevalence of 25% – nearly two times higher than people without COPD. This prevalence increases to 57% in patients with severe COPD, of whom 18% have major depression and only 6% receive treatment.Citation65 The prevalence of anxiety in patients with COPD is also high, and the two conditions frequently occur concurrently in the same patient. Generalized anxiety disorders can occur in 10%–33% of patients with COPD, and the prevalence of disorders and panic attacks ranges from 8%–67%.Citation66 Untreated depressive symptoms are associated with a decrease in adherence to medical treatment and pulmonary rehabilitation, lower exercise capacity, higher mortality and hospital readmissions, and substantial impairments in psychological, physical, and social functioning, along with a worsening of HRQoL.Citation67–Citation69 In a recent meta-analysis, comorbid depression or anxiety increased the risk of mortality in COPD patients (depression relative risk = 1.83; 95% CI = 1.00–3.36), (anxiety relative risk = 1.27; 95% CI = 1.02–1.58) and increased the risk of COPD exacerbation by 31%.Citation70 In addition to pharmacological treatment, several nonpharmacological therapies such as pulmonary rehabilitation, psychotherapy, educational sessions, relaxation therapy, and group cognitive behavioral therapy can improve depression scores.Citation71–Citation75 A systematic review showed that psychological interventions and lifestyle interventions that include an exercise component significantly improve symptoms of depression and anxiety by 28% and 23%, respectively, in people with COPD. The best results were observed with programs based on multicomponent exercise training, with a decrease in depression and anxiety symptoms of 47% and 45%, respectively.Citation76

Improvement of physical activity

Patients with COPD have lower levels of physical activity than the general population. In COPD patients, greater physical activity correlated significantly with improvement in dyspnea, HRQoL, and mobility.Citation77 However, a moderate relationship exists between daily physical activity and exercise capacity, suggesting that exercise interventions need to target not only exercise capacity but also behavioral changes with regard to daily physical activity, in order to achieve improvement in both parameters. Additionally, the increased exercise capacity achieved with pulmonary rehabilitation may not be accompanied by increased daily physical activity.Citation78

Several studies have evaluated the beneficial role of physical activity in the prognosis and evolution of COPD. In one cohort study with 11 years of follow-up, smokers with moderate or high levels of exercise had lower risk for developing COPD than did smokers with low levels of exercise. In addition, this study showed that a higher level of physical activity decreased the loss of lung function, both in smokers and in former smokers.Citation79

Reduction in physical activity is a well-known consequence of COPD, but inactivity is itself a cause that contributes to the greater loss of pulmonary function, so that smokers with low levels of physical activity are more likely to develop COPD. Physical exercise lowers oxidative stress, has an anti-inflammatory effect, and reduces the frequency of respiratory tract infections, providing a number of mechanisms that could mitigate the harmful effects of smoking.Citation80

The results of a recent study in primary care in Spain demonstrated that individual counseling is effective in increasing physical activity in inactive people. The effect is small but significant in terms of public health at the population level.Citation81 This effect is greater in patients with chronic diseases. Furthermore, there is evidence indicating that physical exercise helps smokers to quit smoking.Citation82 Additionally, daily walking intensity is related to HRQoL, as measured with a generic questionnaire (SF-36) and a specific questionnaire for COPD (SGRQ), and to decreased biomarkers related to cardiac distress in stable COPD patients.Citation83

Prevention of malnutrition

Disease-related malnutrition is a common problem in individuals with COPD, with 30%–60% of inpatients and 10%–45% of outpatients said to be at risk.Citation84 Malnourished COPD patients demonstrate greater gas trapping, lower diffusing capacity, and a reduced exercise performance when compared with heavier, nonmalnourished patients with a similar severity of disease.Citation85 The relationship between malnutrition and COPD is not completely elucidated; malnutrition may be the consequence of greater disease severity, but it may also be a factor in the wasting of peripheral and respiratory muscles involved in breathing or the impairment of the immunological system, accelerating COPD progression. Interestingly, in chronic anorexia nervosa, the loss of body weight is accompanied by a loss of lung tissue, mimicking emphysematous-like changes.Citation86

Assessment of the patient’s nutritional status becomes a necessity for early detection of increased risk for malnutrition and establishes the degree of nutritional support to apply. In a recent systematic review, nutritional support was not associated with improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second, although it showed a significant increase in maximal inspiratory and expiratory capacity and sternomastoid and quadriceps strength, and a reduction in fatigability.Citation87 Other studies have shown improvement in HRQoL and well-being in malnourished COPD subjects who received nutritional support.Citation88 Finally, another systematic review from the Cochrane collaboration showed improvement in the distance covered in the 6-minute walking test (39.96 m; 95% CI = 22.66–57.26 m).Citation89 In contrast, for other COPD patients, obesity is an important and increasing problem that limits exercise capacity, producing restriction and aggravating respiratory dyspnea.Citation90

Smoking cessation

Smoking is a major risk factor for developing COPD, and smoking cessation is a priority in the management of the disease. Despite clear evidence linking smoking with morbidity and mortality in COPD, a third or more of patients with moderate and severe COPD continue to smoke.Citation91 Smoking COPD patients have a lower HRQoL than nonsmokers and a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms, even in the same respiratory disease category and severity grade.Citation92 Smoking cessation has been related to HRQoL improvement.Citation93 In COPD patients, intensive counseling and pharmacotherapy resulted in comparable results for individuals who stopped smoking and the general population.Citation94

Self-management programs

Self-management programs are defined as “any formalized patient education programme aimed at teaching skills needed to carry out medical regimens specific to the disease, guide health behavior change, and provide emotional support for patients to control their disease and live functional lives.”Citation95 These programs aim to develop patients’ coping skills to maintain as active a lifestyle as possible, promote correct use of drugs, and encourage the early identification of increasing symptoms heralding an exacerbation so that they can be treated early. In a meta-analysis, self-management improved HRQoL measured with SGRQ but did not reach a clinically relevant improvement of four points.Citation95 Self-management is also related to the use of less rescue medication, reduction in unscheduled doctor and nurse visits, and a possible reduction in hospitalizations for COPD exacerbation.Citation45 In a recent study, self-management did not decrease hospital admissions in the overall study population, although only 42% of the intervention groups were classified as successful self-managers at the end of the study period on the basis of their recognition and appropriate use of treatment. Interestingly, this subgroup of successful self-managers had a significantly reduced risk for readmission or death. Younger patients and those not living alone are more likely to correctly use self-management techniques and derive benefit from them.Citation96 More recently, a self-management intervention based on behavioral changes in patients and health care providers with an emphasis on motivational interviewing and a greater alliance between patient and interventionist showed promising results, with improvements in QoL and patient acceptability.Citation97

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a broad therapeutic concept that includes conditioning, breathing retraining, education, and psychological support, and it comprises lower- and upper-extremities exercise, ventilatory-muscle training, education to improve medication compliance, smoking cessation, nutrition, exercise, psychological support, and health preservation. Integrated into the individualized treatment of the patient, pulmonary rehabilitation is designed to reduce symptoms, optimize functional status, improve activity and daily function, and restore the highest level of independent physical function in patients with COPD by stabilizing or reversing systemic manifestations of the disease.Citation98

Several studies and meta-analyses have shown that pulmonary rehabilitation improves HRQoL more than pharmacological treatment does. This improvement is observed even in the absence of clinically significant improvements in exercise. A Cochrane meta-analysis of 31 randomized controlled trials, 13 of which measured QoL, indicated that HRQoL measured with the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire or the SGRQ improved and exceeded the minimal clinically important difference with pulmonary rehabilitation.Citation99

Increase in medication adherence

Access to drugs alone is not sufficient to control chronic conditions. According to the World Health Organization, adherence to long-term therapy for chronic illnesses in developed countries averages 50%.Citation100 It is undeniable that many patients experience difficulty in following treatment recommendations. In a recent study, 18% of the respiratory patients interviewed quit the therapy spontaneously; the first cause of this discontinuation was the complexity of treatment, even though the patients reported that doctors’ explanations of the respiratory treatment were, on average, quite suitable.Citation101 Data from the Towards a Revolution in COPD Health study demonstrate that poor adherence to inhaled therapy is more frequent in patients with poorer HRQoL and is associated with increased risk of exacerbations and mortality.Citation102 Nonadherence is a multidetermined problem caused by, among others factors, the patient–provider relationship, the complexity of the therapy, the immediacy of beneficial effects, and patient education and knowledge of the disease.Citation103 Inherent in the definition of “compliance” is the idea that patients are passive, acquiescent recipients of expert medical advice with which they should comply. For this reason, some authors prefer the term “adherence,” which reflects a more active patient role in consenting to and following prescribed treatments; more recently, the term “concordance” has been used to describe the “therapeutic alliance” that exists between patients and health care professionals. Pharmacological therapy of COPD is largely based in inhaled therapy, and therefore correct education and training in inhaler devices is essential to ensure compliance. Strategies to enhance adherence include simplifying the dose, choosing the inhaler device on the basis of patient characteristics, involving caregivers or family members as a useful support to care, providing information in both written and verbal forms, and establishing a good patient–physician relationship.Citation104

Telehealthcare management

Telehealthcare is the provision of personalized health care over a distance. It has three essential components: (1) the patient provides data about the illness (symptoms, oxygen saturation, sputum); (2) information is transferred electronically to a health care professional at a second location; and (3) the health care professional uses clinical skills and judgment to provide personalized feedback to the patient.Citation105 Although telehealthcare theoretically should improve HRQoL and reduce hospital admissions by allowing early detection of exacerbations and by involving patients in self-management of the disease, study results are controversial. A systematic review of nine published studies showed that telehealthcare was effective in reducing the length of stay in hospital and emergency department visits by 21% but found a nonsignificantly increased death rate (hazard ratio = 1.21; 95% CI = 0.84–1.75) in the telephone-support group compared with the usual-care group, nor was there a significant difference in QoL or patient satisfaction with the service between the two groups.Citation106 Similar results showing a decrease in hospital admission rates and in the total number of exacerbations without significant changes in HRQoL were reported by Trappenburg et al.Citation107 In a recent Cochrane review, telehealthcare was associated with a clinically significant increase in HRQoL and a significant reduction in emergency department attendance and hospitalizations, without differences in 1-year survival.Citation108 Some authors suggest that telehealthcare could reduce HRQoL and psychological well-being owing to the increased burden of self-monitoring, concerns about intrusive surveillance, a perceived lack of user-friendliness, and the undermining of the traditional (face-to-face) therapeutic relationship. The effects of telehealthcare might not be uniform across all patients, and analyses may suggest subgroups of patients for whom telehealthcare is either particularly beneficial or harmful.Citation109,Citation110

Other therapies

In some studies, cognitive behavioral therapy – a structured psychological intervention in which the patient works collaboratively with the therapist to identify the types and effects of thoughts, beliefs, and interpretations on current symptoms, feeling states and/or problem areas – achieved improvements in QoL, anxiety, depression, and control of panic attacks.Citation71,Citation111,Citation112 Similarly, relaxation therapy improved dyspnea and psychological well-being.Citation113

Conclusion

In addition to drug treatment, several nonpharmacological therapies have been shown to be useful in improving symptoms and QoL in patients with COPD. These measures may be especially useful in the management of patients with COPD and multiple comorbidities, which also may require an adaptation of the model of care to avoid fragmentation of attention among multiple specialists. Prevention of disability, malnutrition, or exacerbations, alongside the treatment of depression and comorbidities, smoking cessation, and increase in physical activity, among other measures, have been associated with HRQoL improvement. A more multidisciplinary approach and individualization of these interventions is crucial in the management of COPD patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationGlobal surveillance, Prevention and Control of Chronic Respiratory Diseases: A Comprehensive ApproachGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2007 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241563468_eng.pdfAccessed March 23, 2013

- LozanoRNaghaviMForemanKGlobal and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592095212823245604

- VosTFlaxmanADNaghaviMYears lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592163219623245607

- López-CamposJLRuiz-RamosMSorianoJBCOPD mortality rates in Andalusia, Spain, 1975–2010: a joinpoint regression analysisInt J Tuberc Lung Dis201317113113623114257

- ErbasBUllahSHyndmanRJScolloMAbramsonMForecasts of COPD mortality in Australia: 2006–2025BMC Med Res Methodol2012121722353210

- AlmagroPSalvadóMGarcia-VidalCRecent improvement in long-term survival after a COPD hospitalisationThorax201065429830220388752

- GeorgePMStoneRABuckinghamRJPurseyNALoweDRobertsCMChanges in NHS organization of care and management of hospital admissions with COPD exacerbations between the national COPD audits of 2003 and 2008QJM20111041085986621622541

- EriksenNVestboJManagement and survival of patients admitted with an exacerbation of COPD: comparison of two Danish patient cohortsClin Respir J20104420821420887343

- AlmagroPLópezFCabreraFJGrupos de Trabajo de EPOC y Paciente Pluripatológico y Edad Avanzada de la Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna. [Comorbidities in patients hospitalized due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A comparative analysis of the ECCO and ESMI studies]Rev Clin Esp20122126281286 Spanish22521437

- CliniEMBeghéBFabbriLMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease is just one component of the complex multimorbidities in patients with COPDAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187766867123540872

- NurmatovUBuckinghamSKendallMEffectiveness of holistic interventions for people with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review of controlled clinical trialsPLoS ONE2012710e4643323110052

- SalisburyCMultimorbidity: redesigning health care for people who use itLancet201238098367922579042

- FelceDPerryJQuality of life: its definition and measurementRes Dev Disabil199516151747701092

- JonesPWIssues concerning health-related quality of life in COPDChest1995107Suppl 5187S193S7743825

- AgborsangayaCBLauDLahtinenMCookeTJohnsonJAHealth-related quality of life and healthcare utilization in multimorbidity: results of a cross-sectional surveyQual Life Res201322479179922684529

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- AgustíASolerJJMolinaJIs the CAT questionnaire sensitive to changes in health status in patients with severe COPD exacerbations?COPD20129549249822958111

- DoddJWMarnsPLClarkALThe COPD Assessment Test (CAT): short- and medium-term response to pulmonary rehabilitationCOPD20129439039422497561

- VestboJHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- RabeKFCooperCBGlobal initiative on obstructive lung disease revisedAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187101035103623675707

- TsiligianniIKocksJTzanakisNSiafakasNvan der MolenTFactors that influence disease-specific quality of life or health status in patients with COPD: a review and meta-analysis of Pearson correlationsPrim Care Respir J201120325726821472192

- TinettiMEFriedTRBoydCMDesigning health care for the most common chronic condition – multimorbidityJAMA2012307232493249422797447

- KadamUTCroftPRNorth Staffordshire GP Consortium GroupClinical multimorbidity and physical function in older adults: a record and health status linkage study in general practiceFam Pract200724541241917698977

- FortinMLapointeLHudonCMultimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic reviewHealth Qual Life Outcomes200425115380021

- AlmagroPCalboEOchoa de EchagüenAMortality after hospitalization for COPDChest200212151441144812006426

- AlmagroPCabreraFJDiezJet al; Working Group onCOPDSpanish Society of Internal MedicineComorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD: the EPOC en Servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) studyChest201214251126113323303399

- FinkelsteinJChaEScharfSMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidityInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009433734919802349

- MüllerovaHAgustiAErqouSMapelDWCardiovascular comorbidity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic literature reviewChest Epub5302013

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with MultimorbidityGuiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for cliniciansJ Am Geriatr Soc20126010E1E2522994865

- BoydCMDarerJBoultCFriedLPBoultLWuAWClinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performanceJAMA2005294671672416091574

- BarnettKMercerSWNorburyMWattGWykeSGuthrieBEpidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional studyLancet20123809836374322579043

- VanfleterenLESpruitMAGroenenMClusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187772873523392440

- FortinMDuboisMFHudonCSoubhiHAlmirallJMultimorbidity and quality of life: a closer lookHealth Qual Life Outcomes200755217683600

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerFWThe influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of comorbidityJ Clin Epidemiol200356121177118414680668

- YeoJKarimovaGBansalSCo-morbidity in older patients with COPD – its impact on health service utilisation and quality of life, a community studyAge Ageing2006351333716364931

- BurgelPREscamillaRPerezTINITIATIVES BPCO Scientific CommitteeImpact of comorbidities on COPD-specific health-related quality of lifeRespir Med2013107223324123098687

- SmithSMSoubhiHFortinMHudonCO’DowdTManaging patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settingsBMJ2012345e520522945950

- SmithSMSoubhiHFortinMHudonCO’DowdTInterventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settingsCochrane Database Syst Rev20124CD00656022513941

- CrisafulliEGorgonePVagagginiBEfficacy of standard rehabilitation in COPD outpatients with comorbiditiesEur Respir J20103651042104820413540

- CorhayJLNguyenDDuysinxBShould we exclude elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from a long-time ambulatory pulmonary rehabilitation programme?J Rehabil Med201244546647222549658

- Weening-DijksterhuisEde GreefMHScherderEJSlaetsJPvan der SchansCPFrail institutionalized older persons: a comprehensive review on physical exercise, physical fitness, activities of daily living, and quality-of-lifeAm J Phys Med Rehabil201190215616820881587

- HalpinDMDecramerMCelliBKestenSLiuDTashkinDPExacerbation frequency and course of COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012765366123055714

- PinnockHKendallMMurraySALiving and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative studyBMJ2011342d14221262897

- MarchettiNCrinerGJAlbertRKPreventing acute exacerbations and hospital admissions in COPDChest201314351444145423648908

- EffingTMonninkhofEMvan der ValkPDSelf-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20074CD00299017943778

- BourbeauJJulienMMaltaisFChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease axis of the Respiratory Network Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du QuébecReduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management interventionArch Intern Med2003163558559112622605

- JeppesenEBrurbergKGVistGEHospital at home for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20125CD00357322592692

- McCurdyBRHospital-at-home programs for patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an evidence-based analysisOnt Health Technol Assess Ser20121210165

- ShepperdSLanninNAClemsonLMMcCluskeyACameronIDBarrasSLDischarge planning from hospital to homeCochrane Database Syst Rev20131CD00031323440778

- GriffithsTLBurrMLCampbellIAResults at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trialLancet2000355920136236810665556

- GüellRCasanPBeldaJLong-term effects of outpatient rehabilitation of COPD: a randomized trialChest2000117497698310767227

- CasasATroostersTGarcia-AymerichJMembers of the CHRONIC ProjectIntegrated care prevents hospitalisations for exacerbations in COPD patientsEur Respir J200628112313016611656

- RiceKLDewanNBloomfieldHEDisease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182789089620075385

- FanVSGazianoJMLewRA comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trialAnn Intern Med20121561067368322586006

- PuhanMAGimeno-SantosEScharplatzMTroostersTWaltersEHSteurerJPulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev201110CD00530521975749

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica para el Tratamiento de Pacientes con Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica (EPOC)Guía de Práctica Clínica para el Tratamiento de Pacientes con Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica (EPOC)Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e IgualdadUnidad de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias de la Agencia Laín Entralgo2012 Guías de Práctica Clínica en el SNS: UETS Nº 2011/6. Available from: http://www.guiasalud.es/GPC/GPC_512_EPOC_Lain_Entr_compl.pdfAccessed Jun 2013

- ReidWDYamabayashiCGoodridgeDExercise prescription for hospitalized people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities: a synthesis of systematic reviewsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012729732022665994

- EisnerMDIribarrenCBlancPDDevelopment of disability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: beyond lung functionThorax201166210811421047868

- EttingerWHCan hospitalization-associated disability be prevented?JAMA2011306161800180122028358

- KrumholzHMPost-hospital syndrome – an acquired, transient condition of generalized riskN Engl J Med2013368210010223301730

- CovinskyKEPierluissiEJohnstonCBHospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure”JAMA2011306161782179322028354

- BraidoFBaiardiniIMenoniSDisability in COPD and its relationship to clinical and patient-reported outcomesCurr Med Res Opin201127598198621385019

- SpruitMAGosselinkRTroostersTMuscle force during an acute exacerbation in hospitalised patients with COPD and its relationship with CXCL8 and IGF-IThorax200358975275612947130

- BachmannSFingerCHussAEggerMStuckAEClough-GorrKMInpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsBMJ2010340c171820406866

- ZhangMWHoRCCheungMWFuEMakAPrevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regressionGen Hosp Psychiatry201133321722321601717

- HillKGeistRGoldsteinRSLacasseYAnxiety and depression in end-stage COPDEur Respir J200831366767718310400

- KeatingALeeAHollandAEWhat prevents people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from attending pulmonary rehabilitation? A systematic reviewChron Respir Dis201182899921596892

- PapaioannouAIBartziokasKTsikrikaSThe impact of depressive symptoms on recovery and outcome of hospitalised COPD exacerbationsEur Respir J201341481582322878874

- OmachiTAKatzPPYelinEHDepression and health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Med20091228778. e9e778. e1519635280

- AtlantisEFaheyPCochraneBSmithSBidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and meta-analysisChest Epub2212013

- de GodoyDVde GodoyRFA randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Phys Med Rehabil20038481154115712917854

- KunikMEBraunUStanleyMAOne session cognitive behavioural therapy for elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychol Med200131471772311352373

- Paz-DíazHMontes de OcaMLópezJMCelliBRPulmonary rehabilitation improves depression, anxiety, dyspnea and health status in patients with COPDAm J Phys Med Rehabil2007861303617304686

- BaraniakASheffieldDThe efficacy of psychologically based interventions to improve anxiety, depression and quality of life in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysisPatient Educ Couns2011831293620447795

- CafarellaPAEffingTWUsmaniZAFrithPATreatments for anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a literature reviewRespirology201217462763822309179

- CoventryPABowerPKeyworthCThe effect of complex interventions on depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS ONE201384e6053223585837

- KatajistoMKupiainenHRantanenPPhysical inactivity in COPD and increased patient perception of dyspneaInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012774375523152679

- ZwerinkMvan der PalenJvan der ValkPBrusse-KeizerMEffingTRelationship between daily physical activity and exercise capacity in patients with COPDRespir Med2013107224224823085213

- Garcia-AymerichJLangePBenetMSchnohrPAntóJMRegular physical activity modifies smoking-related lung function decline and reduces risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007175545846317158282

- HopkinsonNSPolkeyMIDoes physical inactivity cause chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?Clin Sci2010118956557220132099

- GrandesGSanchezASanchez-PinillaROPEPAF GroupEffectiveness of physical activity advice and prescription by physicians in routine primary care: a cluster randomized trialArch Intern Med2009169769470119364999

- UssherMHTaylorAFaulknerGExercise interventions for smoking cessationCochrane Database Syst Rev20084CD00229518843632

- JehnMSchindlerCMeyerATammMSchmidt-TrucksässAStolzDDaily walking intensity as a predictor of quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Sci Sports Exerc20124471212121822293866

- CollinsPFEliaMStrattonRJNutritional support and functional capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisRespirology201318461662923432923

- EzzellLJensenGLMalnutrition in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Clin Nutr20007261415141611101463

- CoxsonHOChanIHMayoJRHlynskyJNakanoYBirminghamCLEarly emphysema in patients with anorexia nervosaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004170774875215256394

- EfthimiouJFlemingJGomesCSpiroSGThe effect of supplementary oral nutrition in poorly nourished patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm Rev Respir Dis19881375107510823057956

- WeekesCEEmeryPWEliaMDietary counselling and food fortification in stable COPD: a randomised trialThorax200964432633119074931

- FerreiraIMBrooksDWhiteJGoldsteinRNutritional supplementation for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev201212CD00099823235577

- Díez-ManglanoJBarquero-RomeroJAlmagroPWorking Group on COPD and the Spanish Society of Internal MedicineCOPD patients with and without metabolic syndrome: clinical and functional differencesIntern Emerg Med Epub552013

- TashkinDPMurrayRPSmoking cessation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med2009103796397419285850

- JosephSPascaleSGeorgesKMirnaWCigarette and waterpipe smoking decrease respiratory quality of life in adults: results from a national cross-sectional studyPulm Med2012201286829422988502

- PapadopoulosGVardavasCILimperiMLinardisAGeorgoudisGBehrakisPSmoking cessation can improve quality of life among COPD patients: validation of the clinical COPD questionnaire into GreekBMC Pulm Med2011111321352544

- HoogendoornMFeenstraTLHoogenveenRTRutten-van MölkenMPLong-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in patients with COPDThorax201065871171820685746

- DislerRTInglisSCDavidsonPMNon-pharmacological management interventions for COPD: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviewsCochrane Database Syst Rev20132CD010384

- BucknallCEMillerGLloydSMGlasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trialBMJ2012344e106022395923

- BenzoRVickersKErnstDTuckerSMcEvoyCLorigKDevelopment and feasibility of a self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease delivered with motivational interviewing strategiesJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev201333211312323434613

- NiciLDonnerCWoutersEATS/ERS Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing CommitteeAmerican Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173121390141316760357

- LacasseYGoldsteinRLassersonTJMartinSPulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20064CD00379317054186

- World Health OrganizationAdherence to long-term therapies: evidence for actionMeeting report June 4–5, 2001Geneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2010 Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdfAccessed March 24, 2013

- SantusPPiccioloSProiettoADoctor-patient relationship: a resource to improve respiratory diseases managementEur J Intern Med201223544244622726373

- VestboJAndersonJACalverleyPMAdherence to inhaled therapy, mortality and hospital admission in COPDThorax2009641193994319703830

- BourbeauJBartlettSJPatient adherence in COPDThorax200863983183818728206

- BischoffEWHamdDHSedenoMEffects of written action plan adherence on COPD exacerbation recoveryThorax2011661263121037270

- McLeanSProttiDSheikhATelehealthcare for long term conditionsBMJ2011342d12021292710

- PolisenaJTranKCimonKHome telehealth for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Telemed Telecare201016312012720197355

- TrappenburgJCNiesinkAde Weert-van OeneGHEffects of telemonitoring in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseTelemed J E Health200814213814618361703

- McLeanSNurmatovULiuJLPagliariCCarJSheikhATelehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20117CD00771821735417

- YohannesAMTelehealthcare management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseExpert Rev Respir Med20126323924222788935

- CartwrightMHiraniSPRixonLWhole Systems Demonstrator Evaluation TeamEffect of telehealth on quality of life and psychological outcomes over 12 months (Whole Systems Demonstrator telehealth questionnaire study): nested study of patient reported outcomes in a pragmatic, cluster randomised controlled trialBMJ2013346f65323444424

- CoventryPAGellatlyJLImproving outcomes for COPD patients with mild-to-moderate anxiety and depression: a systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapyBr J Health Psychol200813Pt 338140017535503

- LivermoreNSharpeLMcKenzieDPrevention of panic attacks and panic disorder in COPDEur Respir J201035355756319741029

- DevineECPearcyJMeta-analysis of the effects of psychoeducational care in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePatient Educ Couns19962921671789006233