Abstract

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) present with a variety of symptoms that significantly impair health-related quality of life. Despite this, COPD treatment and its management are mainly based on lung function assessments. There is increasing evidence that conventional lung function measures alone do not correlate well with COPD symptoms and their associated impact on patients’ everyday lives. Instead, symptoms should be assessed routinely, preferably by using patient-centered questionnaires that provide a more accurate guide to the actual burden of COPD. Numerous questionnaires have been developed in an attempt to find a simple and reliable tool to use in everyday clinical practice. In this paper, we review three such patient-reported questionnaires recommended by the latest Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines, ie, the modified Medical Research Council questionnaire, the clinical COPD questionnaire, and the COPD Assessment Test, as well as other symptom-specific questionnaires that are currently being developed.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a multicomponent and heterogeneous disease, with patients differing in terms of clinical presentation and rate of disease progression.Citation1–Citation3 Some patients can live their lives almost untouched by the disease, while others are almost completely handicapped.Citation4 A major goal in the management of this disease is to ensure that its burden is minimized, such that patients have the best possible health-related quality of life. Traditionally, the severity of the disease was equated with airflow limitation, as measured by impairment in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), and treatment and management of COPD was also largely based on spirometric assessment.Citation5 However, because COPD is a multicomponent disorder, structural and functional changes take place in other organs, as well as in the lungs.Citation2 Therefore, airflow limitation alone does not reflect the full burden of COPD and it is perhaps not surprising that FEV1 correlates poorly with patient-centered outcomes, such as dyspnea, exercise intolerance, and impairment of health-related quality of life.Citation1,Citation3,Citation6

Generally, patients seek medical help when their COPD symptoms begin to have a substantial impact on their daily lives,Citation7,Citation8 either directly or indirectly (when patients have to adjust their lifestyle to avoid these symptoms). These symptoms reflect the daily burden encountered by patients with COPD and have a real impact on their well-being.Citation4,Citation9–Citation12 In fact, the symptoms of COPD are more closely related to health-related quality of life than is airway obstruction, suggesting that health-related quality of life is affected more by symptoms than by changes in FEV1.Citation4,Citation13–Citation15

Reflecting these findings, a multidimensional assessment and management approach is now recommended in the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) COPD strategy document.Citation5 This is based on a combined assessment of the impact of the patient’s symptoms on their life (measured by the modified Medical Research Council [mMRC] questionnaire, the clinical COPD questionnaire [CCQ]Citation16 or the COPD Assessment Test [CAT]Citation3), and an assessment of the patient’s future risk of experiencing an exacerbation.Citation5 This classification allows patients to be placed into four groups: group A (less symptoms, low risk), group B (more symptoms, less risk), group C (less symptoms, high risk), and group D (more symptoms, high risk).

In a recent publication, 6,628 patients with COPD were stratified into these new four GOLD groups and compared with the former GOLD classification that was based solely on percent predicted post-bronchodilator FEV1.Citation17 Group B patients (more symptoms, less risk) had higher mortality than group C patients (less symptoms, high risk), suggesting that dyspnea played a greater predictive role in mortality than airflow limitation in this group of patients. Group B patients also had a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as heart disease and cancer. Thus, while the GOLD classification system provides a framework for optimizing treatment decisions, physicians also need to consider the consequences of comorbidities and other serious events on the management of the disease.

Symptoms of COPD and their impact on everyday life

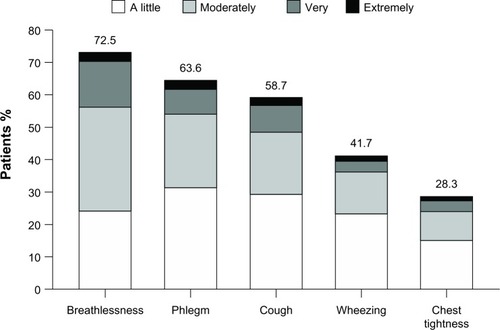

The characteristic respiratory symptoms of COPD include dyspnea (at rest and during exercise), chronic cough, sputum production, and other non-specific diurnally variable symptoms such as wheeze and chest tightness ().Citation3,Citation16,Citation18–Citation20

Figure 1 Symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

© 2011 European Respiratory Society. Reproduced with permission of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J. February 2011;37:264–272; published ahead of print November 29, 2010; DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00051110.

Patients report dyspnea to be the most bothersome symptom of COPD, and this is the primary reason for patients seeking medical care.Citation21 Dyspnea onset is gradual and patients often mistakenly relate it to aging or a lack of fitness. Nonetheless, epidemiologic studies indicate that, as lung function worsens, dyspnea becomes more persistent and intrusive,Citation22 and is a major cause of anxiety for patients and a leading cause of disability.Citation23,Citation24

While dyspnea is considered the hallmark symptom, cough is often the first COPD symptom to develop.Citation8 Chronic cough and sputum production in COPD are predictive of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and disease progression,Citation20 and are associated with lower health-related quality of life than that of patients with other chronic respiratory diseases in which cough is a prominent symptom, eg, asthma and bronchiectasis.Citation25 COPD is also known to have a significant extrapulmonary impact, and can be associated with systemic symptoms such as fatigue, muscle weakness, weight loss, and sleep disturbances.Citation26

COPD leads to a significant reduction in ability to exercise. Physical activity is reduced even in patients with mild or moderate airflow limitation, and declines significantly as airflow worsens in severity.Citation27,Citation28 Thus, to avoid dyspnea, patients often restrict their physical activities,Citation9,Citation27,Citation29 but this leads to a downward spiral of symptom-induced inactivity (deconditioning aggravates breathlessness and patients tend to compensate by reducing activity further).Citation30,Citation31 This is important because the amount of physical activity a patient is able to perform and their functional status predict exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality.Citation32–Citation34

Previously, it was believed that symptoms of COPD presented with little or no variability. However, patients frequently report “good” and “bad” days, with evidence showing that patient symptoms fluctuate within a day, from day to day, and over longer periods of time.Citation19,Citation35–Citation37 Symptoms are often worst in the mornings compared with other times of the day, and mornings are the most troublesome part of the day for many patients.Citation19,Citation36,Citation37 Nevertheless, patients with COPD also complain frequently of difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep.Citation38,Citation39 These sleep disturbances affect health-related quality of life, and are also predictive of COPD exacerbations, emergency health care utilization, and mortality.Citation39,Citation40

The combination of dyspnea, decreased physical activity, and patients’ perceptions of these abnormalities leads to a reduction in health-related quality of life,Citation31,Citation41 with the most significant factors being dyspnea, depression, anxiety, and reduced exercise tolerance.Citation4 Therefore, from a patient’s perspective, improvement in symptoms and the ability to engage in activities of daily life are extremely desirable goals of COPD management.

Why is it important to measure symptoms routinely in practice?

Despite considerable disability, patients with COPD often underestimate the severity of their disease, perhaps due in part to lifestyle adaptations to avoid symptoms.Citation12,Citation42,Citation43 Often patients present to physicians only when their condition has deteriorated significantly and they are experiencing significant symptoms, especially dyspnea, reduced exercise performance, and impaired health-related quality of life.Citation6,Citation8,Citation44

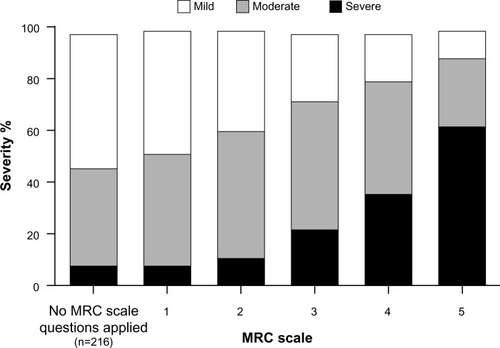

Considerable discrepancy between COPD symptoms and patients’ perceptions of health-related quality of life is also evident. For example, an international survey of 3,304 patients with COPD revealed that disease severity perceptions did not correspond to dyspnea severity,Citation12 as measured by the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea scale (adapted as per Bestall et alCitation23), and 36% of 210 patients who were too breathless to leave the house, and 60% of 639 patients who had to stop for breath every few minutes when walking on level ground, considered their disease to be mild or moderate (see , including definitions for the 0–5 breathlessness scale used; note there are a number of different versions of the MRC (eg, MRC [1–5], Bestall MRC [0–5], and mMRC [0–4])). Similar results were observed in the PLATINO (Latin American Project for Research in Pulmonary Obstruction) studyCitation43 using the mMRC questionnaire, where “good” to “excellent” health was reported by more than half of patients with COPD, despite a dyspnea severity of mMRC level 2 (walks slower than people of the same age on level ground because of dyspnea) or 3 (stops for breath after walking 100 m or after a few minutes on level ground). These discrepancies may cause clinicians to undertreat patients by not appreciating the actual impact of the disease.

Figure 2 Self-reported perceived severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (mild, moderate, or severe) reported by degree of breathlessness, adapted and reproduced.Citation12

© 2002 European Respiratory Society. Reproduced with permission of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J. October 2002 20:799–805; DOI:10.1183/09031936. 02.03242002.

Abbreviation: MRC, Medical Research Council.

If physicians can measure the severity and impact of key COPD symptoms quickly and reliably, they can gain a better understanding of their patients’ overall clinical status and are able to adjust their proposed treatment accordingly. As discussed in the GOLD strategy, pharmacologic therapy reduces symptoms and exacerbations and improves health status and exercise tolerance in COPD, while rehabilitation also helps to improve exercise tolerance and quality of life and reduces symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue in patients with breathlessness.Citation5 Further, by measuring these symptoms in a routine manner via questionnaires in advance of the consultation, they may also gain time and efficiency.Citation45 Therefore, there is a clear need for specially designed, patient-reported outcome tools that meet these needs and measure key COPD symptoms such as dyspnea, as well as lifestyle adaptations, functional status, exercise tolerance, and health-related quality of life.Citation3,Citation4,Citation6,Citation18,Citation30

In recent years, COPD management has shifted towards optimizing symptom control and reducing future risks, such as exacerbations, mortality, and comorbidities, as well as the long-term consequences of COPD.Citation46 More research is required to understand fully the relationship between these two aims. However, presence of respiratory symptoms can predict long-term outcomes in patients with mild airflow limitation (GOLD stage 1), such as increased respiratory care utilization and a lower health-related quality of life.Citation47 Dyspnea measurements in COPD have been demonstrated to predict general health statusCitation14 and exercise performance after pulmonary rehabilitation.Citation48 Moreover, categorizing patients with COPD based on their level of dyspnea correlates closely with 5-year survival, moreso than staging of disease severity based on lung function alone.Citation49 Thus, while prevention and treatment of symptoms may not prevent long-term lung function decline, symptom control could provide measurable improvements in other key outcomes.

How to quantify symptoms?

The most efficient and transparent way for physicians to assess patient symptom severity, activity limitation, and health-related quality of life accurately is to use a quick, reliable, and standardized measure, such as a short patient-centered questionnaire. Such structured questionnaires go beyond the “How are you?” questions that tend to be used in clinical practice, providing more specific information that will help determine aspects of the disease that are most important for the individual patient. Many instruments used in research, such as the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire,Citation50 were designed for use in clinical trials, include numerous questions and are not suitable for use in daily clinical practice. There are numerous instruments available to assess symptoms, but this review will focus on the three recommended by GOLD 2013, ie, the mMRC dyspnea scale (a breathlessness measure), the CCQ (a health status measure), and the CAT (another health status measure).Citation5

Modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale

The mMRC dyspnea scale is simple to administer and is used for grading the effect of breathlessness (dyspnea) on daily activities. The mMRC actually measures perceived respiratory disability, allowing patients to indicate the extent to which their dyspnea symptoms affect their activities. Patients select one of five statements that most closely corresponds to their level of impairment, from grade 0 (“I only get breathless with strenuous exercise”) to grade 4 (“I am too breathless to leave the house or I am breathless when dressing or undressing”).Citation5 The mMRC scale is a reliable measure, with a high rate of concordant scores (98%) between different observers rating the same patient.Citation51 It also correlates well with results of other dyspnea scales, lung function measurements,Citation51 and direct measures of disability, such as walking distance.Citation52 However, the disadvantage of the mMRC over other scales is its insensitivity to change; it is uncommon for patients with COPD to improve or worsen by an entire grade due to therapeutic intervention.Citation53,Citation54 Also, the mMRC does not take into account the variation in effort exerted by patients in activities and the fact that patients modify behavior in response to dyspnea.Citation54 Further, FEV1 does not relate to disability using the mMRC scale and it is possible that lack of variation across the mMRC grades is too small to measure.Citation23

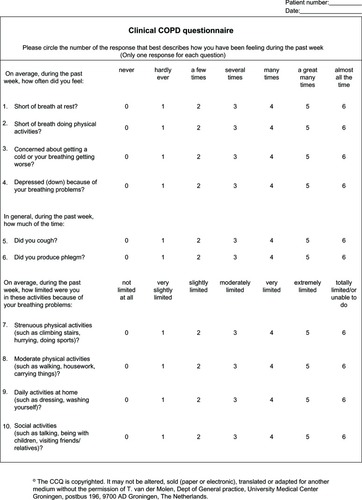

Clinical COPD questionnaire

The CCQ has recently been incorporated into the GOLD assessment of COPD symptoms.Citation5 It was developed in 2003 following recognition of the need for physicians to have a more complete understanding of the impact of COPD on their patients, not only regarding clinical status of the airways but also activity limitation and emotional dysfunction.Citation16 The ten items included in this self-administered patient questionnaire were selected based on information gathered from a literature search, clinicians, and patients, and with experts and clinicians in COPD making the final item selection. The CCQ assesses three domains, ie, symptoms (dyspnea, cough, and phlegm), functional state, and mental state (). The overall CCQ score and each of the three individual domain scores vary between 0 and 6 (least to worst impairment). There is strong supporting evidence for the reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the CCQ.Citation42,Citation55 The CCQ has also been shown to be very sensitive to clinical improvement after smoking cessation,Citation16,Citation56 and during and after exacerbations.Citation57 Further, contrary to expectations, the total CCQ score correlates well with lung function (as assessed by FEV1 percent predicted) in patients with COPD, although this relationship was limited to patients with GOLD airflow limitation grades 1–3.Citation16 The CCQ correlates with the Short Form-36 and the St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireCitation16 to a moderate to high extent. Studies have shown that CCQ scores can predict depression and anxiety in patients with COPD.Citation4,Citation11 Because the CCQ is simple and quick to use, taking around 2 minutes to complete, data can be processed instantly. Therefore, it is a useful tool that can be used in the everyday clinical setting to assess COPD.Citation42

Figure 3 Clinical COPD questionnaire.Citation16

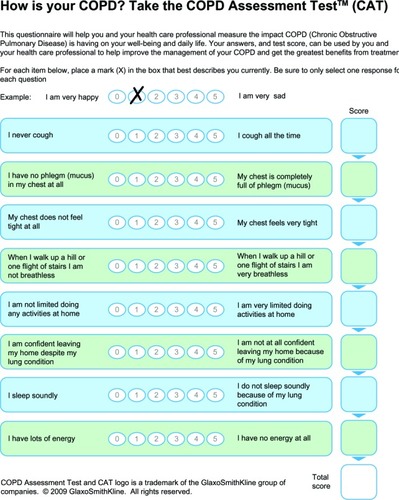

COPD Assessment Test

The CAT was developed in 2009 to measure the impact of COPD on health-related quality of life and to aid patient-physician communication.Citation3 It was developed based on qualitative research among physicians and over 1,500 patients across six countries. The final patient-completed questionnaire is simple and easy to administer, designed for routine use in clinical practice, and takes around 2 minutes to complete; and has a short time scale similar to the CCQ. The eight items included in the CAT cover cough, phlegm, chest tightness, breathlessness going up hills and stairs, activity limitation at home, confidence leaving home, sleep, and energy (). Therefore, it has a broad coverage of the impact of COPD on the patient’s daily life. Further, there is strong reliability evidence for the CAT, and preliminary data for its construct and discriminant validity.Citation3,Citation42,Citation58 Although brief and simple to use, the CAT has nevertheless shown responsiveness to pulmonary rehabilitation and in assessing recovery from an exacerbation,Citation59,Citation60 a strong impairment in health-related quality of life due to COPD.Citation3,Citation58 A similarly strong correlation has been demonstrated between CCQ and CAT scores.Citation4 Indeed, in a group of patients with severe COPD undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation, a good correlation was found between the CAT, CCQ, and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.Citation61

MCID for questionnaires

The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) has been defined as “the smallest difference in a score in the domain of interest that patients perceive as beneficial that would mandate, in the absence of troublesome side effects and excessive costs, a change in the patient’s management”.Citation62 There are two key constructs to this definition, ie, the minimal amount of change reported by patients and change significant enough to alter patient management. When used in the context of a clinical trial, the MCID provides a conceptual framework to help interpret the clinical relevance of results, by indicating how much the tested therapy has improved the patient’s health-related quality of life.Citation63

The mMRC has only five grades, so has limited sensitivity to detect changes in response to treatment. However, a difference of one grade is considered to indicate a perceived change in dyspnea of clinical significance.Citation64 The MCID for CCQ has been calculated based on three methods: the patient referencing method (determined by judgment of the patient on the basis of a Global Rating of Change questionnaire); the criterion referencing method and the standard error of measurement method (which seeks correlations between single standard error units and established MCID approximations). Using these three varying methods, the MCID for CCQ has been calculated to be 0.44 units, 0.39 units, and 0.21 units, respectively.Citation65 Therefore, it has been suggested that the MCID for the CCQ total score should be set at 0.4 units.Citation65

An MCID for the CAT has not been established officially, but has been estimated to be around 2 units.Citation58,Citation59 However, there is some debate as to the value that should be used.Citation66 In one study, the MCID was estimated to be 1.4 units based on a comparison with the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire,Citation58 although there has been criticism of this approach in calculating the MCID.Citation66 Using the same study data and the standard error of measurement distribution method, the MCID for the CAT was calculated to be 6.75.Citation66 This highlights some of the difficulties associated with determining MCID in patient-reported outcomes, when there is no accepted methodology.Citation63

What are these questionnaires missing?

The questionnaires described above were developed in order to identify and manage problems considered to be important to patients, and which aim to meet both patient and clinician goals for the management of this disease. However, although the CCQ and CAT scales were developed with input from both patients and physicians, they offer no way of discriminating between what clinicians consider as important and what is important to patients but less so to clinicians. One example of this is fatigue: the impact of treatment on fatigue is limited and this symptom is perceived as being difficult to treat by clinicians. Further, less well recognized symptoms, such as hyper-responsiveness due to ongoing inflammation and signs of comorbidities, are not represented in these questionnaires. Therefore, although incorporation of the questionnaires into routine clinical practice will undoubtedly help identify symptoms that have an impact on patient well-being and optimize the management of COPD, there may be other symptoms and factors that influence health-related quality of life for individual patients.

Further COPD symptom questionnaires

Questionnaires that measure specific symptoms associated with COPD other than dyspnea may be useful in clinical practice when monitoring specific symptoms experienced by individual patients. For example, a questionnaire designed to monitor cough may be useful for patients who have chronic cough or who are experiencing an exacerbation. In this regard, the Cough and Sputum Assessment Questionnaire, the Leicester Cough Questionnaire, and the Cough Quality of Life Questionnaire may prove to be useful tools.Citation25,Citation67 Given that the morning appears to be an especially troublesome time of the day for symptoms, particularly cough and dyspnea, there is also a need for patient-reported outcome questionnaires that assess the burden and extent of these morning symptoms, as well as the ability of patients to perform morning activities.Citation68 Two questionnaires, based on interviews with patients, have been developed, validated, and shown to be responsive and reliable. The first is the Capacity of Daily Living during the Morning questionnaire, which asks patients to report on their ability to carry out six different activities and then to rank the difficulty of performing these on a five-point Likert scale. The second is the Global Chest Symptoms Questionnaire, which consists of two questions that require the patient to rate shortness of breath and chest tightness, again on a five-point Likert scale.Citation68

Similarly, although there is evidence that fatigue and sleep impairment are frequent problems in patients with COPD,Citation39 there is little available data to help quantify these important aspects of COPD. Our understanding may be improved by the introduction of two questionnaires that have recently been developed and validated in patients with COPD and asthma to assess these symptoms.Citation69 As their names suggest, the 12-item questionnaire COPD and Asthma Fatigue Scale assesses fatigue and the 13-item questionnaire COPD and Asthma Sleep Impact Scale assesses sleep-related problems and disorders.

Phenotype-based management of COPD

The recent revision of the GOLD documentCitation5 has proposed treatment of COPD directed by the intensity of symptoms (measured by the mMRC, CCQ, or CAT) and the risk of poor outcomes (identified by the degree of airflow obstruction and/or frequency of exacerbation). However, the GOLD 2013 strategy document does not recommend different treatment approaches based on clinical characteristics (ie, phenotypes) of patients. The recent Spanish guideline for treatment of COPD (Guía Española de la EPOC) takes a different approach, proposing four clinical phenotypes on which pharmacologic treatment can be based: infrequent exacerbator, with either chronic bronchitis or emphysema; mixed or overlap COPD-asthma; frequent exacerbator with predominant emphysema; and frequent exacerbator with predominant chronic bronchitis.Citation70,Citation71 These guidelines recommend that infrequent exacerbators (defined as a patient experiencing fewer than two exacerbations a year) should only receive bronchodilators. COPD exacerbators who frequently present with chronic bronchitis (defined as the presence of productive cough or expectoration for more than 3 months a year for more than 2 consecutive years) can be treated with bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids, and/or phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, with antibiotics as indicated (eg, for bronchiectasis). Patients who have an exacerbator with an emphysema phenotype (ie, without chronic cough and sputum production and typical clinical and radiologic signs of emphysema) can be treated with long-acting bronchodilators, and in some cases, inhaled corticosteroids. Finally, patients with the overlap COPD-asthma phenotype show an enhanced response to inhaled corticosteroids due to the presence of eosinophilic bronchial inflammation. Therefore, patient-reported outcome questionnaires will help to identify these patient phenotypes and allow for optimal pharmacologic treatment to be implemented.

How to use questionnaires in daily clinical practice: example from primary care

In many cultures and health care settings, patients tend to dislike completing questionnaires, preferring instead to talk to their doctor. Clinicians may also have trouble completing questionnaires in daily clinical practice. Nevertheless, when both clinician and patient become used to using them, the information transfer becomes accurate, to the point, and efficient for both clinician and patient, leaving more time for advice and other important issues during the consultation. One way to overcome initial hesitation about using questionnaires is to organize the diagnostic and follow-up process so that questionnaires are included routinely. With careful organization, the process can be made transparent and transferable. In a primary care setting in Groningen, The Netherlands, patients with respiratory symptoms using inhaled medication are asked to complete the CCQ at home, plus a history questionnaire and the Asthma Control Questionnaire. They then come to the office for spirometry assessments, and data from the spirometry tests and questionnaires are fed into an Internet-based system. The local pulmonologist accesses all these data through the Internet, so is able to assess the patient and, in 86% of cases, give advice about diagnosis and treatment to the general practitioner.Citation4 To date, approximately 12,000 patients have been assessed using this system; 45% of patients were diagnosed with asthma, 17% with COPD, and 7% with a combination of both asthma and COPD.Citation72 Previously, Lucas et al showed that a paper-based system using the same principles was reliable and accurate in its diagnosis.Citation73

Although the diagnosis of COPD is based on post-bronchodilator forced expiratory FEV1, disease severity is also based on number of exacerbations and health-related quality of life, as measured by the CCQ. Cross-sectional data show that 27% of patients with COPD in primary care have poor health-related quality of life, as indicated by a CCQ score of >2.Citation4 Given that poor health-related quality of life can be present in patients with mild disease (GOLD stages 1 and 2), fully understanding patients’ health-related quality of life can have a considerable impact on patient management, in addition to what is known about their lung function.

Conclusion

Traditional lung function assessments alone do not provide enough insight into the impact of COPD on patients’ health-related quality of life. FEV1 does not correlate strongly with health-related quality of life. Further, patients often do not communicate their current health-related quality of life accurately to the physician. Instead, routine assessment of the impact of COPD, including symptoms and their effect on daily activity, using validated and reliable questionnaires such as the CCQ, CAT, and mMRC, provides a more accurate guide to the burden of this disease. Implementation of quick and easy-to-use questionnaires in routine clinical practice is an efficient way to help physicians understand fully the health-related quality of life of their patients, improve transparency, and enable appropriate treatment to be prescribed and monitored.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the manuscript, data analysis, contributed to the writing of each draft of the manuscript, and approved the final contents.

Disclosure

TvdM has received research grants from AstraZeneca, GSK, Nicomed, MSD, and Allmiral, consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Nicomed, MSD, Novartis, and Allmiral, and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GSK, Nicomed, Novartis, and MSD. MM has received speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering, Novartis, Talecris-Grifols, Takeda-Nycomed, MSD, and Novartis, and consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, GSK, AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering, Novartis, Almirall, MSD, Talecris-Grifols, and Takeda-Nycomed. JWHK has received grants from Stichting Zorgdraad, and fees for lectures from GSK. He has received travel grants from GSK, Chiesi, and Boehringer Ingelheim. He also acts as an advisor for GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis. The authors were assisted in preparation of the manuscript by Melanie Stephens (Circle-Science, UK) and Henry Maseruka (Novartis). This assistance was funded by Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland).

References

- AgustiACalverleyPMCelliBCharacterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Res20101112220831787

- JonesPWHealth status measurement in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2001561188088711641515

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- TsiligianniIGvan der MolenTMoraitakiDAssessing health status in COPD. A head-to-head comparison between the COPD assessment test (CAT) and the clinical COPD questionnaire (CCQ)BMC Pulm Med2012122022607459

- global Initiative for Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2011 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.comAccessed July 25, 2013

- CazzolaMMacNeeWMartinezFJOutcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkersEur Respir J200831241646918238951

- KaplanAMarciniukDBouchardJTessierLPatient symptoms dictate how physicians behave in the early diagnosis of COPDPrim Care Respir J2011202A6

- KornmannOBeehKMBeierJNewly diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical features and distribution of the novel stages of the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung DiseaseRespiration2003701677512584394

- BarnettMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a phenomenological study of patients’ experiencesJ Clin Nurs200514780581216000094

- O’DonnellDImpacting patient-centred outcomes in COPD: breathlessness and exercise toleranceEur Respir Rev2006154246

- ClelandJALeeAJHallSAssociations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patientsFam Pract200724321722317504776

- RennardSDecramerMCalverleyPMImpact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: subjects’ perspective of confronting COPD International SurveyEur Respir J200220479980512412667

- HajiroTNishimuraKTsukinoMA comparison of the level of dyspnea vs disease severity in indicating the health-related quality of life of patients with COPDChest199911661632163710593787

- MahlerDAFaryniarzKTomlinsonDImpact of dyspnea and physiologic function on general health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChest199210223954011643921

- SchlechtNFSchwartzmanKBourbeauJDyspnea as clinical indicator in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChron Respir Dis20052418319116541601

- van der MolenTWillemseBWSchokkerSDevelopment, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD QuestionnaireHealth Qual Life Outcomes200311312773199

- LangePMarottJLVestboJPrediction of the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, using the new GOLD classification: a study of the general populationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121861097598122997207

- JonesPMiravitllesMvan der MolenTKulichKBeyond FEV(1) in COPD: a review of patient-reported outcomes and their measurementInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012769770923093901

- KesslerRPartridgeMRMiravitllesMSymptom variability in patients with severe COPD: a pan-European cross-sectional studyEur Respir J201137226427221115606

- MiravitllesMCough and sputum production as risk factors for poor outcomes in patients with COPDRespir Med201110581118112821353517

- WitekTJJrMahlerDAMinimal important difference of the Transition Dyspnoea Index in a multinational clinical trialEur Respir J200321226727212608440

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- HillKGeistRGoldsteinRSLacasseYAnxiety and depression in end-stage COPDEur Respir J200831366767718310400

- PolleyLYamanNHeaneyLImpact of cough across different chronic respiratory diseases: comparison of two cough-specific health-related quality of life questionnairesChest2008134229530218071022

- AgustiAGNogueraASauledaJSystemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200321234736012608452

- CooperCBAirflow obstruction and exerciseRespir Med2009103332533419071004

- WatzHWaschkiBMeyerTMagnussenHPhysical activity in patients with COPDEur Respir J200933226227219010994

- PittaFTroostersTSpruitMACharacteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171997297715665324

- ReardonJZLareauSCZuWallackRFunctional status and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Med200611910 Suppl 1323716996897

- ZuWallackRHow are you doing? What are you doing? Differing perspectives in the assessment of individuals with COPDCOPD20074329329717729076

- Garcia-AymerichJLangePBenetMSchnohrPAntoJMRegular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort studyThorax200661977277816738033

- KocksJWAsijeeGMTsiligianniIGKerstjensHAvan der MolenTFunctional status measurement in COPD: a review of available methods and their feasibility in primary carePrim Care Respir J201120326927521523316

- PittaFTroostersTProbstVSPhysical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPDChest2006129353654416537849

- GilbertCMartinMLHareendranACapturing individual variation in the experience of symptoms reported by patients with COPDAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007175A15A100417633759

- Espinosa de los MonterosMJPenaCSoto HurtadoEJJarenoJMiravitllesMVariability of respiratory symptoms in severe COPDArch Bronconeumol20124813721944843

- PartridgeMRKarlssonNSmallIRPatient insight into the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the morning: an Internet surveyCurr Med Res Opin20092582043204819569976

- CormickWOlsonLGHensleyMJSaundersNANocturnal hypoxaemia and quality of sleep in patients with chronic obstructive lung diseaseThorax198641118468543824271

- ScharfSMMaimonNSimon-TuvalTSleep quality predicts quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011611221311688

- OmachiTABlancPDClamanDMDisturbed sleep among COPD patients is longitudinally associated with mortality and adverse COPD outcomesSleep Med201213547648322429651

- JonesPWIssues concerning health-related quality of life in COPDChest1995107Suppl 5187S193S7743825

- JonesPWPriceDvan der MolenTRole of clinical questionnaires in optimizing everyday care of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011628929621697993

- Montes de OcaMTalamoCHalbertRJHealth status perception and airflow obstruction in five Latin American cities: the PLATINO studyRespir Med200910391376138219364640

- CruseMAThe impact of change in exercise tolerance on activities of daily living and quality of life in COPD: a patient’s perspectiveCOPD20074327928117729073

- Gruffydd-JonesKMarsdenHCHolmesSUtility of COPD Assessment Test (CAT) in primary care consultations: a randomised controlled trialPrim Care Respir J2013221374323282858

- PostmaDAnzuetoACalverleyPA new perspective on optimal care for patients with COPDPrim Care Respir J201120220520921559550

- BridevauxPOGerbaseMWProbst-HenschNMLong-term decline in lung function, utilisation of care and quality of life in modified GOLD stage 1 COPDThorax200863976877418505800

- JacobsenRFrolichAGodtfredsenNSImpact of exercise capacity on dyspnea and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev20123229210022193931

- NishimuraKIzumiTTsukinoMOgaTDyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPDChest200212151434144012006425

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPA self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireAm Rev Respir Dis19921456132113271595997

- MahlerDAWellsCKEvaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspneaChest19889335805863342669

- McGavinCRArtvinliMNaoeHMcHardyGJDyspnoea, disability, and distance walked: comparison of estimates of exercise performance in respiratory diseaseBMJ197826132241243678885

- HaughneyJGruffydd-JonesKPatient-centred outcomes in primary care management of CPrim Care Respir J200413418519716701668

- RiesALImpact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on quality of life: the role of dyspneaAm J Med200611910 Suppl 1122016996895

- KocksJWKerstjensHASnijdersSLHealth status in routine clinical practice: validity of the clinical COPD questionnaire at the individual patient levelHealth Qual Life Outcomes2010813521080960

- RedaAAKotzDKocksJWWesselingGvan SchayckCPReliability and validity of the clinical COPD questionniare and chronic respiratory questionnaireRespir Med2010104111675168220538445

- KocksJWvan den BergJWKerstjensHADay-to-day measurement of patient-reported outcomes in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2013827328623766644

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWProperties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European studyEur Respir J2011381293521565915

- DoddJWHoggLNolanJThe COPD assessment test (CAT): response to pulmonary rehabilitation. A multicentre, prospective studyThorax201166542542921398686

- JonesPWHardingGWiklundITests of the responsiveness of the COPD assessment test following acute exacerbation and pulmonary rehabilitationChest2012142113414022281796

- RingbaekTMartinezGLangePA comparison of the assessment of quality of life with CAT, CCQ, and SGRQ in COPD patients participating in pulmonary rehabilitationCOPD201291121522292593

- JaeschkeRSingerJGuyattGHMeasurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important differenceControl Clin Trials19891044074152691207

- JonesPWInterpreting thresholds for a clinically significant change in health status in asthma and COPDEur Respir J200219339840411936514

- de TorresJPPinto-PlataVIngenitoEPower of outcome measurements to detect clinically significant changes in pulmonary rehabilitation of patients with COPDChest200212141092109811948037

- KocksJWTuinengaMGUilSMHealth status measurement in COPD: the minimal clinically important difference of the clinical COPD questionnaireRespir Res200676216603063

- KocksJWTsiligianniIGvan der MolenTResponsiveness of the COPD assessment test: the minimal clinically important difference does matterChest2012142126726822796862

- MonzBUSachsPMcDonaldJResponsiveness of the cough and sputum assessment questionnaire in exacerbations of COPD and chronic bronchitisRespir Med2010104453454119917525

- PartridgeMRMiravitllesMStahlEDevelopment and validation of the Capacity of Daily Living during the Morning questionnaire and the Global Chest Symptoms Questionnaire in COPDEur Respir J20103619610419897551

- MiravitllesMIriberriMBarruecoMUsefulness of the LCOPD, CAFS and CASIS scales in understanding the impact of COPD on patientsRespiration1022012 [Epub ahead of print.]

- MiravitllesMSoler-CatalunaJJCalleMSpanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC): pharmacological treatment of stable COPD. Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic SurgeryArch Bronconeumol201248724725722561012

- MiravitllesMJose Soler-CatalunaJCalleMSorianoJBTreatment of COPD by clinical phenotypes. Putting old evidence into clinical practiceEur Respir J20134161252125623060631

- MettingEIRiemersmaRASandermanRvan der MolenTKocksJWDescription of a Dutch well-established asthma/COPD service for primary carePrim Care Respir J201322A1A18

- LucasAESmeenkFJvan den BorneBESmeeleIJvan SchayckCPDiagnostic assessments of spirometry and medical history data by respiratory specialists supporting primary care: are they reliable?Prim Care Respir J200918317718419139795