Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Age and smoking are common risk factors for COPD and other illnesses, often leading COPD patients to demonstrate multiple coexisting comorbidities. COPD exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity in individual patients. Clinical trials investigating the treatment of COPD routinely exclude patients with multiple comorbidities or advanced age. Clinical practice guidelines for a specific disease do not usually address comorbidities in their recommendations. However, the management and the medical intervention in COPD patients with comorbidities need a holistic approach that is not clearly established worldwide. This holistic approach should include the specific burden of each comorbidity in the COPD severity classification scale. Further, the pharmacological and nonpharmacological management should also include optimal interventions and risk factor modifications simultaneously for all diseases. All health care specialists in COPD management need to work together with professionals specialized in the management of the other major chronic diseases in order to provide a multidisciplinary approach to COPD patients with multiple diseases. In this review, we focus on the major comorbidities that affect COPD patients. We present an overview of the problems faced, the reasons and risk factors for the most commonly encountered comorbidities, and the burden on health care costs. We also provide a rationale for approaching the therapeutic options of the COPD patient afflicted by comorbidity.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially among smokers over 40 years of age and individuals exposed to biomass smoke.Citation1 The World Health Organization estimates that COPD will be the third most common worldwide cause of death and disability by 2030, from its current fifth ranking.Citation2 Despite worldwide medical research, health care efforts, and health care costs, COPD statistics reveal a continuing upward trend in mortality, in contrast with other major causes of death like cancer and cardiovascular disease.Citation2 A major factor that complicates therapeutic approaches to the management of COPD is that COPD is rarely the only chronic illness a patient has to contend with. Age and smoking are the major risk factors for COPD and a number of other illnesses, often leading to COPD patients demonstrating multiple coexisting comorbidities.Citation3,Citation4

The presence of comorbidities is so strongly associated with the management of COPD that the need for thorough attention to them is emphasized even in the COPD definition by GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) guidelines:Citation5 “Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a common preventable and treatable disease, is characterized by airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to noxious particles or gases. Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity in individual patients.” Comorbidities are most often responsible for impairing quality of life for early-stage patients,Citation6 for increasing mortality in end-stage patients, for increasing the burden of COPD management on health care costs, and creating therapeutic dilemmas for health care providers.Citation5

COPD comorbidities is a rather broad heterogeneous term, including diseases that independently coexist with COPD with no other causation, diseases that share common risk factors and pathogenetic pathways with COPD, diseases that are complicated by the interaction with the lung, and systemic manifestations of COPD, and vice versa. This heterogeneity has given rise in recent years to a conceptual discussion about the appropriateness of the term “comorbidities”, in an attempt to establish an agreement over its meaning. No universal definition has yet been accepted. Terminology issues though should not shift our focus from the fact that COPD patients with multiple diseases often have poorer outcomes and are in need of a more complex, tailored therapeutic intervention approachCitation7,Citation8 in order to optimize and achieve better outcomes.

For this review, we consider as common comorbidities all previously described diseases that frequently coexist with COPD, without discriminating between those directly related and those not. The underlying causes of multimorbidity in COPD are not yet fully recognized. There is an increasing abundance of evidence that associates COPD with other age-driven diseases and diseases that share common risk factors (smoking) or etiological pathways.Citation3 This view is supported by the widely accepted hypothesis that COPD sustains systematic inflammation.Citation9 Most commonly COPD is associated with lung cancer and other cancers, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, dysfunctional skeletal myopathies, osteoporosis, and mental disorders. Although these associations are part of our established knowledge about the disease, precise prevalence numbers differ in the published epidemiological studies (see ).Citation3 There is a need to identify from the extensive pool of comorbidities those which are more strongly associated with a significantly increased risk of death in COPD individuals. Divo et al in a recent report concluded that lung, pancreatic, esophageal, and breast cancers (the last only for female patients), pulmonary fibrosis, atrial fibrillation/flutter, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, gastric/duodenal ulcers, liver cirrhosis, diabetes with neuropathy, and anxiety are the most significant and frequent comorbidities.Citation10 Clinical practice guidelines usually mention but seldom address comorbidities practically in their recommendations. Furthermore, clinical trials investigating COPD treatment routinely exclude patients with multiple comorbidities or advanced age;Citation11 the latter enormously affects the external validity and generalizability of the effectiveness of the treatments tested in the large clinical trials.

Table 1 Prevalence of the most common COPD comorbidities (%)

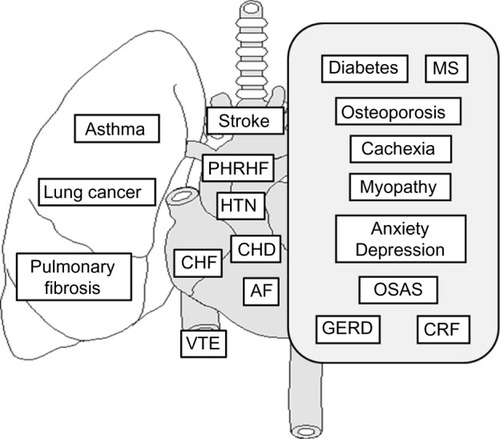

In this review, we focus on the major comorbidities that affect COPD patients, present an overview of the problems they face, the reasons and risk factors for the most commonly encountered comorbidities (), the burden on health care costs, and provide a rationale for approaching the therapeutic options for the COPD patient afflicted by comorbidity.

Figure 1 The most common and clinically important comorbidities in patients with COPD.

Respiratory comorbidities

Asthma

Both asthma and COPD are major chronic obstructive airway diseases that involve underlying airway inflammation. COPD is characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible, is usually progressive, and is associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs to noxious particles or gases. Individuals with asthma who are exposed to noxious agents (particularly cigarette smoking) may develop fixed airflow limitation and a mixture of “asthma-like” inflammation and “COPD-like” inflammation. Thus, even though asthma can usually be distinguished from COPD, in some individuals who develop chronic respiratory symptoms and fixed airflow limitation, it may be difficult to differentiate the two diseases. In some patients with chronic asthma, a clear distinction from COPD is not possible using current imaging and physiological testing techniques, and it is assumed that asthma and COPD coexist in these patients. In these cases, current management includes use of anti-inflammatory drugs, and other therapies need to be individualized. Other potential diagnoses are usually easier to distinguish from COPD.Citation5

Coexistence of asthma and COPD in elderly patients is often diagnosed.Citation12 In some studies, the overlap diagnosis of asthma and COPD exceeds half of the patients examined.Citation13,Citation14 The overlap is identified by finding increased variability of airflow in patients with incompletely reversible airway obstruction.Citation15 The presence of COPD-asthma overlap syndrome is associated with impaired quality of life and more frequent and severe exacerbations compared with COPD only patients.Citation16

The coexistence of asthma and COPD cannot be excluded even in the study populations of the biggest COPD clinical trials. In UPLIFT, a 4-year trial of tiotropium in COPD, 5,993 patients were enrolled.Citation17 At visit 2 of the study, prebronchodilator spirometry was performed and the patients then received an enhanced bronchodilation test including four inhalations of ipratropium (80 mg via metered-dose inhaler) followed 60 minutes later by four inhalations of salbutamol (400 mg via metered-dose inhaler) to ensure maximal or near-maximal bronchodilation. The majority of the study population with moderate-to-very severe COPD demonstrated meaningful increases in lung function following administration of inhaled anticholinergic plus sympathomimetic bronchodilators: 65.6% of the patients met the criterion of a ≥15% increase in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and 53.9% met the criterion of an increase in FEV1 of both ≥12% and ≥200 mL.Citation18

In ECLIPSE, a large observational study (2,138 COPD patients), researchers tested the hypothesis that there is a frequent-exacerbation phenotype of COPD that is independent of disease severity.Citation19 The single best predictor of exacerbations, across all GOLD stages, was a history of exacerbations. The second strongest predictor of exacerbations was a history of reflux or heartburn, a common symptom among asthma patients.

Although the overlap syndrome seems to be a common clinical presentation, both the major COPD guidelines (GOLD) and asthma guidelines (GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma) do not give specific recommendations for its combined treatment at the moment.

In August 2014, a joint project regarding the diagnosis of diseases of chronic airflow limitation (Asthma, COPD, and Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome [ACOS]) was published by the science committees of GOLD and GINA.Citation20 This document was based on a detailed review of available literature and consensus. It provides an approach to distinguishing between asthma, COPD, and the overlap of asthma and COPD, for which the term ACOS is proposed. A stepwise approach to diagnosis is advised, comprising recognition of the presence of a chronic airways disease, syndromic categorization as asthma, COPD, or ACOS, confirmation by spirometry and, if necessary, referral for specialized investigations.

Lung cancer

COPD patients run an increased risk of developing lung cancer. It is also a factor that contributes to poorer outcomes in lung cancer patients.Citation20,Citation21 The prevalence of COPD among patients with lung cancer varies from 40% to 70%.Citation22,Citation23 Lung cancer patients tend to have more severe lung function impairment. Several reports confirmed that lung cancer occurs in COPD patients late in the natural course of the disease. The prevalence of moderate-to-very severe disease (GOLD stages II–IV) among lung cancer patients reaches 50%, in contrast with only 8% of smokers without lung cancer.Citation20 The annual incidence of lung cancer is four times higher in COPD patients when compared with the general population.Citation20,Citation24

Both diseases create management difficulties for one another, but therapy for lung cancer is more crucially affected. Mainly due to impaired lung function, patients with COPD often fail to meet the tolerance criteria for undergoing surgical resection of their otherwise operable malignancy. The result is that the overall prognosis for patients with both diseases is worse than each alone. Three-year survival in patients with COPD and lung cancer has been found to be around 15%, compared with 26% for lung cancer patients without COPD.Citation20 Lung cancers, together with cardiovascular comorbidities, are the leading causes of death in COPD patients with mild-to-moderate disease, while respiratory failure due to airway obstruction only becomes predominant in advanced COPD.Citation25–Citation27

Pulmonary fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis is more common among smokers, and in coexistence with emphysema it has been classified as a distinct clinical entity (combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome).Citation28 Patients with coexistence of pulmonary interstitial fibrosis and COPD present characteristic lung function tests, with relatively normal spirometry and lung volumes but severely impaired gas exchange. This results from the inverse effect of airway traction of pulmonary fibrosis on bronchus constriction of COPD. Simultaneously, gas exchange is impaired by both thickening of the alveolar membrane in pulmonary fibrosis and reduction of the vascular surface in emphysema. Compared with pulmonary fibrosis or emphysema alone, patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome have more frequent and more severe pulmonary hypertension. Patients with the syndrome face a reduced survival prognosis compared with patients with COPD, with an estimated median survival of 6 years.Citation24,Citation29

Cardiovascular comorbidities

Hypertension

Hypertension is very common in COPD patients, but is not associated with increased mortality.Citation10 Hypertension is related to the increased systemic inflammation observed in COPD and is correlated with higher Medical Research Council dyspnea scores, reduced capacity for physical activity,Citation30 and airflow obstruction.Citation31

Congestive heart failure

Congestive heart failure and COPD share similar risk factors, especially whatever risk factor is associated with smoking, and common pathophysiological mechanisms, which frequently coexist in the same patient.Citation32 The prevalence of congestive heart failure among COPD patients varies between stable disease and exacerbations. In stable COPD studies report a 3.8% to 16% coexistence compared with exacerbations that reach up to 48%.Citation33,Citation34 Congestive heart failure is among the leading causes of hospitalization and death for patients with COPD and worsens their prognosis.Citation35 Simultaneously, COPD is an independent risk factor for death in patients with congestive heart failure.Citation36 Coexistence of COPD and congestive heart failure worsens right ventricular dysfunction, when compared with non-COPD patients.Citation37 Left ventricular dysfunction is present in around 20% of COPD patients, but frequently goes unnoticed.Citation38

Coronary heart disease

COPD and coronary heart disease share a common major risk factor, which is smoking. The coexistence has been reported to be as high as 30% or even higher in COPD patients. Vigilance in recognizing and diagnosing coronary disease signs and symptoms is needed in assessing COPD patients.Citation39 In some studies of the medical records of COPD patients, undiagnosed cases of coronary heart disease reach 70%.Citation40 Addressing undiagnosed cases is crucial for improving outcomes, since the coexistence of both diseases worsens the prognosis when compared with each separately. Both diseases are characterized by chronic sustained inflammation and coagulopathy. The key mediator of this sustained inflammation in COPD is probably elevated C-reactive protein levels, which not only maintain bronchial constriction but also increase the risk for coronary disease.Citation24,Citation41

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation and COPD are two common morbidities and often coexist.Citation42 The presence and severity of COPD are associated with increased risk for atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia among COPD patients has been reported to be as high as 23.3% and 13.0%, respectively.Citation43 Reduced FEV1 and COPD are associated with a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation after adjustment for confounders.Citation44 The prevalence of COPD in patients with atrial fibrillation reaches 18%.Citation45 Hospitalization mortality in severe COPD patients with arrhythmia has been reported to be as high as 31%, compared with 8% in non-COPD patients.Citation46 Prolonged conduction time in the right atrium and typical atrial flutter are commonly observed in COPD patients with atrial fibrillation.Citation47

Pulmonary artery hypertension and subsequent right heart failure

Pulmonary artery hypertension and subsequent right heart failure are observed in COPD patients as a consequence of pulmonary artery remodeling. This remodeling occurs in COPD due to endothelial dysfunction, clotting abnormalities, hypoxic vasoconstriction, destruction of the pulmonary capillary bed, inflammatory infiltration of the vascular wall, and shear stress due to blood flow redistribution.Citation48 Reports estimate that the prevalence of pulmonary artery hypertension in COPD patients is as high as 40%.Citation49 When COPD patients develop pulmonary artery hypertension, they experience more intense shortness of breath, greater desaturation during exercise, and more profound limitation of physical activity. The coexistence of COPD and pulmonary artery hypertension is associated with higher mortality.Citation50 Signs and symptoms of right ventricular dysfunction should be recognized, although diagnosis of pulmonary artery hypertension does not improve management outcomes in COPD. Addition of long-term oxygen therapy has a stabilizing effect in some patients.Citation24,Citation51

Venous thromboembolism

The prevalence of venous thromboembolism in COPD patients during an exacerbation has been reported to be as high as 29%.Citation52,Citation53 The prevalence of pulmonary embolism in COPD patients is also documented to be higher than in non-COPD patients and increases with age.Citation54 The risk of venous thromboembolism is higher in patients with COPD and other comorbidities like hypertension, coronary artery disease, or cancer, or with previous surgery. Venous thromboembolism prolongs hospitalization by 4.4 days and increases one-year mortality by 30%.Citation53 If not diagnosed and treated adequately, the risk of death during hospitalization for exacerbations is increased by 25%. COPD not only shares certain common risk factors with venous thromboembolism, like smoking, but also systemic inflammation due to COPD induces pulmonaryCitation55 and systemic endothelial dysfunctionCitation56 and coagulopathy.Citation24,Citation57,Citation58

Stroke

COPD patients present an increased risk for ischemic stroke, as a result of common risk factors, like age and smoking, and the systemic inflammation and coagulopathy caused by COPD.Citation59,Citation60 There is a linear correlation between stroke risk and airflow obstruction.Citation61 Almost 8% of all COPD patients have a history of stroke.Citation62 About 4% of all deaths in COPD patients are related to an incident of ischemic stroke.Citation63

Metabolic comorbidities

Diabetes and metabolic syndrome

Diabetes has been reported in several studies to be a frequent COPD comorbidity, with a prevalence as high as 18.7% among COPD patients.Citation64,Citation65 The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is reported to be up to 22.5% in COPD patients. COPD patients have a relatively increased risk of developing diabetes,Citation66,Citation67 but also diabetes often presents before diagnosis of COPD, and diabetic patients have an increased risk of developing COPD.Citation68 This side-by-side development of both diseases is a result of common risk factors, like smoking, and also the synergic effect of systemic inflammation mediated by common cytokines.Citation69–Citation71 Diabetes worsens the outcomes of COPD by affecting a number of parameters:Citation66,Citation72,Citation73 shortening time to first hospitalization and increasing hospitalization time and risk of death during exacerbations,Citation74 increasing Medical Research Council dyspnea scores, and reducing six-minute walking distance.Citation30 Diabetes worsens 5-year mortality in COPD patients.Citation24,Citation66

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is another chronic illness that frequently coexists with COPD, even in male patients.Citation75,Citation76 The prevalence of osteoporosis among COPD patients ranges up to 69% in some reports, reflecting not only common risk factors, like age and cigarette smoking, but also the harmful effects of COPD due to systemic inflammation, reduced physical activity, and in some cases oral steroid therapy.Citation77 At the same time, vertebral fractures due to osteoporosis lead to decreased rib mobility and frequently to kyphosis, which further impairs lung mechanics.Citation78 Even asymptomatic vertebral fractures accelerate lung function decline.Citation79 Osteoporosis is associated with higher dyspnea scores and reduced six-minute walking distance.Citation30 Patients with COPD and osteoporosis tend to have lower body mass index values and more severe airway obstruction.Citation80

Cachexia and myopathy

Loss of fat-free mass (cachexia) and skeletal muscle dysfunction (myopathy) are common comorbidities with COPD. Both are more common in northern countries, compared with the Mediterranean, probably as a result of dietary differences.Citation11 The prevalence of cachexia among COPD patients ranges from 10% to 15% in mild-to-moderate disease to up to 50% in severe disease,Citation81 even in obese patients.Citation82 The prevalence of skeletal muscle weakness has been reported to be as high as 32% among COPD patients.Citation83 Skeletal muscle weakness shares common risk factors with COPD, like age and smoking, but is also affected by systemic manifestations of COPD, like systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and physical inactivity.Citation84 Skeletal muscle weakness is associated with reduced strength, endurance and exercise capacity, lack of physical activity, impaired quality of life, increased risk for hospital admission after exacerbation, increased health care utilization, and increased risk of death.Citation85–Citation87 Early onset of muscle weakness may reflect a more aggressive COPD phenotype.Citation11

Mental comorbidities

Anxiety and depression frequently accompany certain chronic illnesses.Citation88–Citation90 Many COPD patients experience transitory mood symptoms during exacerbations, which improve spontaneously after recovery. Identifying COPD patients with clinical depression and/or anxiety remains a challenge.Citation91

Anxiety is also more frequent among COPD patients, compared with the general population or patients with other chronic illnesses, with a prevalence reported to be as high as 19%.Citation92 Patients with anxiety tend to have their first hospitalization earlier in the natural course of COPD,Citation93 they are earlier and more intensely irritated by their shortness of breath, and have higher rates of mortality and readmission after an exacerbation.Citation94 Anxiety is one of the known comorbidities with the highest risk of death, especially among female patients,Citation95 that needs adequate attention as it is a potentially treatable condition.Citation96

The prevalence of depression in COPD patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy reaches as high as 60%.Citation97 Depression reduces physical activity, quality of life scores,Citation98,Citation99 and adherence to medical treatment,Citation100 and is associated with higher rates of COPD exacerbationsCitation101,Citation102 and increased mortality.Citation103 Almost 25% of all COPD patients suffer from depression that eludes diagnosis,Citation104 and an estimated two thirds of patients with coexistent COPD and depression do not receive any antidepressant treatment.Citation88,Citation105

Other comorbidities

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is no more common in COPD that in the general population, as previously believed. Results from the Sleep Heart Health Study, after stratification for body mass index and age, give a prevalence for OSAS of around 14% among COPD patients 40 years and older.Citation106 However, the fact that OSAS is a common clinical entity in the general population gives a significant number of cases of coexistence with COPD. The combination leads to increased risk of deathCitation107,Citation108 due to more frequent exacerbations and an increased risk for development of cardiovascular comorbidities like pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.Citation24,Citation109

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is commonly associated with asthma. Little attention has been paid to symptoms of GERD in COPD patients. Studies show a significant prevalence of GERD in up to 60% of COPD patients,Citation110–Citation112 which is correlated more with quality of life scores on the COPD Assessment Test than with airway obstructionCitation113 and risk for exacerbation.Citation19,Citation114 These findings raise more questions as to whether COPD patients are dealing with an independent comorbidity or if there is an unnoticed strong asthma component in their disease.

Chronic renal failure

Renal complications of COPD are common, especially in patients with hypoxemia and hypercapnea.Citation115 The arterial rigidity and endothelial dysfunction caused by COPD frequently lead to a decreased normal renal functional reserve.Citation116 Impairment of renal functional reserve in COPD patients is correlated with more severe airway obstruction and inflammation.Citation116 COPD patients have approximately twice the incidence of acute renal failure, and three times the prevalence of diagnosed chronic renal failure than age-matched and gender-matched controls.Citation115 Renal insufficiency may be present in around 22% of COPD patients.Citation117 Chronic renal failure often goes undiagnosed, and is a particular concern in elderly COPD patients and in COPD patients with cachexia.Citation118 Among COPD patients over 64 years of age, 25% may have chronic renal failure even with normal serum creatinine values.Citation97

Links between COPD and comorbidities

COPD comorbidities include clinical conditions that share common risk factors and pathogenetic pathways with COPD, ie, diseases that are consequences of COPD and diseases that just coexist with COPD due to their large prevalence in the general population but affect outcomes such as hospitalization rates and mortality. As our knowledge of COPD and of the pathogenesis of COPD comorbidities is gradually elucidated by basic science data, the more the complexity of the interactions involved becomes apparent. As COPD becomes more and more understood as a systematic inflammatory disease, our focus is shifting from the lungs.Citation119

Smoking and biomass exposure, along with genetic predisposition, are the major risk factors for developing COPD.Citation5 Age is also a common risk factor for developing COPD, but should not be overestimated. For example, COPD is often considered to be a disease of the later years, but estimates suggest that 50% of those with COPD are now younger than 65 years of age.Citation120

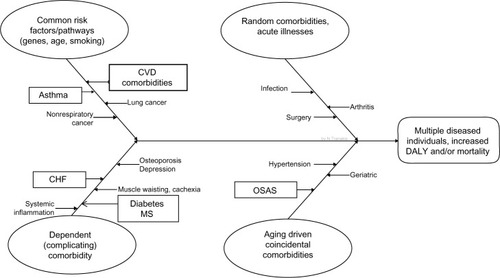

The cause-effect diagram () shows the four ways that comorbidities may complicate COPD. Even if this eye-catching presentation tends to oversimplify the underlying interactions involved, the predominant cause-effect relationships are summarized. Lung cancer and COPD may share certain risk factors, like age, smoking, or genetic predisposition, but bronchial and systemic inflammation due to COPD may also contribute to carcinogenesis, swifting cancer to dependent comorbidity.Citation121,Citation122 The same is evident in several cardiovascular diseases, which also share common risk factors and seem to have a bidirectional inflammatory link with COPD that impairs outcomes for both diseases.Citation123,Citation124 Type 2 diabetes has been considered as a coincidental comorbidity, but evidence is accumulating in favor of considering diabetes and metabolic syndrome as dependent comorbidities.Citation125

Figure 2 Cause-effect diagram shows the four different ways in which other abnormalities may be linked with COPD, presented in the same individual, the so-called multidiseased COPD patient, and leading in increase morbidity and mortality.

Systemic inflammation is the key for linking COPD and most of its dependent comorbidities.Citation119,Citation126 Without over looking other pathways, like hypoxia and oxidative stress, the mainstream approach is that a variety of inflammatory mediators, including interferon-γ, interleukin-1, C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, surfactant protein D, fibrinogen, and amyloid protein, from the peripheral airways enter circulation and affect multiple distal organs.Citation24,Citation126,Citation127 The opposite route is also evident, with inflammatory mediators produced in other organs, due to chronic conditions like heart failure or coronary disease, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of COPD structural abnormalities. Some researchers go as far as to propose that COPD is just a manifestation of a systemic inflammatory syndrome.Citation71

COPD medications may also contribute to the development or worsening of certain comorbidities.Citation88 Bronchodilators are suspected of causing tachyarrhythmias and tremors, but recent randomized clinical trials of long-acting β-agonists suggest that these effects probably do not increase cardiovascular mortality.Citation128,Citation129 Inhaled anticholinergics can affect intraocular pressure and bladder function and might have cardiovascular effects.Citation130,Citation131 Inhaled corticosteroids may increase the risk for cataracts, skin bruising, osteoporosis, and pneumonia.Citation128 Systemic corticosteroids, often overprescribed in COPD patients, could contribute to diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, muscle dysfunction, and adrenal insufficiency.Citation88 On the other hand, heart, liver, and kidney comorbidities need to be taken into account in terms of pharmacokinetic changes and pharmacodynamic modifications, which may lead to unfavorable side effects with suboptimal treatment.Citation4,Citation132

Burden on health care costs

COPD remains a major health issue with a significant economic impact.Citation133 The prevalence of COPD is rising in developing and developed countries, resulting in increased direct and indirect costs of COPD to health care systems worldwide.

In the USA, direct costs have escalated from 18 billion dollars in 2002 to 29.5 billion in 2010, the largest part consisting of hospital expenses,Citation134 whereas indirect costs accounted for 27%–61% of total costs, with the higher estimates produced by studies of working age populations.Citation135,Citation136 Average lifetime earnings losses for COPD patients retiring early have been estimated to be $316,000 per individual.Citation120 In Europe, the total annual cost of COPD is estimated at €38.7 billion.Citation137

The total annual direct costs of COPD expenditure are directly associated with the number of comorbidities,Citation138 not the severity of airflow obstruction or health-related quality of life indices.Citation139 Comorbidities, after age and chronic symptoms, are the factors most predictive of future health care costs.Citation140 COPD patients with comorbidities have increased riskCitation66 and significantly higher mean costs for hospital admissions.Citation141 Hospitalizations are the greatest contributor to total COPD costs, and account for up to 87% of total COPD-related costs.Citation142 Exacerbations are the leading but not the only cause of hospital admissions, and account for between 40% and 75% of the total health care cost of COPD,Citation143,Citation144 despite treatment with maintenance medications.Citation133 Elevated costs in comorbid COPD patients are not only associated with hospitalizations: COPD patients use approximately 50% more cardiovascular agents than age-matched and sex-matched controls, and almost twice as many antibiotics, analgesics, and psychotherapeutic medications.Citation138

COPD patients with multiple comorbidities make use of a disproportionately large percentage of the total overall health care expenditure on COPD.Citation142,Citation145 The median cost of COPD patients with multiple comorbidities has been found to be 4.7 times higher compared with comorbidity-free COPD patients.Citation139 At the same time, compared with non-COPD controls, COPD patients consume 3.4 times more health care resources.Citation139

It is obvious that holistic medical interventions are urgently needed for COPD management in order to decrease direct and indirect costs. These interventions must aim to reduce exacerbations of the disease and should emphasize personalized therapy according to different COPD phenotypes.

Multimorbidities and outcomes

Comorbidities seem to be present in the majority of COPD patients. Studies show that up to 94% of COPD patients have at least one comorbid disease and up to 46% have three or more.Citation146 Even after correcting outcomes for age, sex, and smoking history, patients with COPD and comorbidities tend to have worse health status and functional impairment.Citation30,Citation147 The presence of three or more comorbidities is a better predictor of impaired health status than any other demographic or clinical variable.Citation148 In mild-to-moderate COPD, lung cancer and cardiovascular comorbidities are the main causes of death and account for up to two thirds of all deaths in these patients, while respiratory failure only becomes predominant in advanced COPD.Citation25–Citation27

The use of health status questionnaires cannot always identify the presence of COPD comorbidities and the risk they pose on affecting outcomes.Citation149 Attempts have been made to measure the relevant effect of multiple concomitant COPD comorbidities on outcomes, especially mortality, using several indexes or scales, which are not always designed exclusively for COPD patients. In these scales, each comorbidity is addressed separately.Citation150 These include the Charlson Comorbidity Index, the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, the Index of Coexisting Disease, and the Kaplan Index.Citation10,Citation151

The COTE index (a COPD-specific comorbidity test) identified 12 comorbidities that predicted death in COPD patients and is suggested as a complementary tool to the BODE (BMI, Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise) index.Citation10 The COMCOLD (COMorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) index addresses the combined effect of COPD comorbidities on mortality and health-related quality of life.Citation152 The use in clinical practice of multiple comorbidity indexes is a powerful tool for better stratifying COPD patients according to their risk for unfavorable outcomes and identifying high-risk patients that need attention paid to tailor-made treatment.

Treatment and management

The cornerstone of management for COPD and comorbidities is guideline-based treatment. The aim of this review is to focus on highlighting important key issues that complicate management of COPD in patients with comorbidities, in order to provide practical guidance for the pulmonary specialist physician in clinical practice. For this reason, we will not repeat in detail what is already established in the guidelines published for each disease.

The management and treatment of COPD is usually based on GOLD guidelines.Citation5 Appropriate treatment (pharmacological and nonpharmacological) can reduce COPD symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health status and exercise tolerance.

The main pharmacological regimens are: β2-agonists, anticholinergics (short-acting and long-acting, SABA-LABA), anticholinergics (short-acting and long-acting, SAMA-LAMA), combination short-acting β2-agonists plus an anticholinergic in one inhaler, combination long-acting β2-agonists plus an anticholinergic in one inhaler, methylxanthines, inhaled corticosteroids, combination long-acting β2-agonists plus corticosteroids in one inhaler, systemic corticosteroids, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors.

LABA have been associated with increased mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure and an increased risk of incident heart failure.Citation153 Tiotropium, on the other hand, has been associated with a reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cardiovascular events.Citation154 Even if few long-term studies have measured changes in bone mineral density, inhaled steroid use for at least 3 years has not been associated with worsening major clinical features of osteoporosis.Citation155 On the other hand, oral corticosteroids can potentially worsen coexistent heart failure, and are associated with an increased risk of arrhythmias.Citation156 If used in COPD, close monitoring for hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis is recommended, as they have potentially harmful adverse effects.Citation157 GOLD guidelines recommend a limited dosage.Citation5 Theophylline is also correlated with increased risk for arrhythmias and atrial fibrillation.Citation158 Each pharmacological treatment regimen needs to be patient-specific, and guided by severity of symptoms, risk of exacerbations, drug availability, and the patient’s response. To date, none of the existing COPD medications have been shown conclusively to modify the long-term decline in lung function.

Patients with asthma and COPD seem to benefit from the use of combinations containing drugs with complementary pharmacological actions. The treatment of patients with asthma or COPD has also led to the discovery and development of drugs having two different primary pharmacological actions in the same molecule, which are now called “bifunctional drugs”.Citation159

The joint project recently published by the science committees of GOLD and GINACitation20 confirms that initial treatment should be selected to ensure that patients with features of asthma receive adequate controller therapy including inhaled corticosteroids but not long-acting bronchodilators alone (as monotherapy), and patients with COPD receive appropriate symptomatic treatment with bronchodilators or combination therapy, but not inhaled corticosteroids alone (as monotherapy).

There is little specific guideline guidance for administering cardiovascular regimens to patients with comorbid COPD.Citation4 As a result, β-blockers are frequently underused in patients with COPD.Citation11 Awareness is needed for patients with congestive heart failure and COPD not to be denied β-blocker treatment.Citation160 Cardioselective β-blockers improve the prognosis without impairing lung function. Caution is needed because cardioselectivity decreases as the dosage escalates.Citation161,Citation162 However, even older nonselective β-blockers are well tolerated in most COPD patients.Citation4 Patients with coronary heart disease should also not be denied the protective effects of β-blockers.Citation163 GOLD guidelines recommend the use of the general coronary disease guidelines, and especially note the use of selective β1-blockers even in patients with severe COPD.Citation2,Citation5 The use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors by smokers may protect against a rapid decline in lung function and progression to COPD.Citation164 Chronic lowering of ACE improves pulmonary inflammation, respiratory muscle function, and peripheral use of oxygen.Citation165 ACE inhibitors and statins are associated in retrospective studies with reduced cardiovascular mortality, lower respiratory morbidity/mortality, and lower lung cancer risk.Citation11 Statins though should be used with caution because they may worsen myopathy and elevate liver enzymes. All medications that metabolize through the cytochrome P450 system can be affected by administration of a statin.Citation166

Treatment of OSAS largely does not differ between patients with COPD and those without. Treatment of COPD patients with OSAS is based on the treatment of constituent diseases (for COPD bronchodilators, inhaled steroids when indicated, rehabilitation, nutrition, domiciliary oxygen when indicated, and for OSA weight loss and application of continuous positive airway pressure [CPAP]).Citation107,Citation108 The goal of treatment is to maintain adequate oxygenation at all times and to prevent sleep-disordered breathing. CPAP remains the accepted standard treatment for OSA, but CPAP alone may not fully correct hypoxemia, so supplemental oxygen may be required.

The large prevalence of concealed and overt chronic kidney failure in COPD patients, especially the elderly, indicates that awareness is needed for monitoring and addressing adverse effects caused mainly by hydrosoluble drugs, which are cleared by the kidney. Special attention is warranted for drugs like thiazides or digoxin, used in the treatment of cardiovascular comorbidities, but also antibiotics commonly used in acute exacerbations of COPD.Citation117,Citation167

The nonpharmacological treatment of COPD patients includes smoking cessation (counseling plus pharmacotherapy), influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, and pulmonary rehabilitation. Pulmonary rehabilitation, a nonpharmacological intervention, has the potential to affect a number of comorbidities alongside COPD, through exercise training, emphasis on self-management and behavioral change, and psychological support.Citation37 Physical activity and regular exercise are proven to be beneficial for multiple comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or musculoskeletal diseases.Citation168–Citation171 Smoking cessation is the most cost-effective method for slowing COPD progression, and has proven beneficial effects on the outcomes of most comorbidities, for which smoking is a major risk factor.Citation24 Despite the abundance of data on smoking, only a small percentage of smokers in the USA have received any kind of smoking cessation intervention.Citation172,Citation173 Similarly, the percentage of the population that currently receives influenza vaccination is also low.Citation172

The harmful and beneficial effects of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments underscore the paramount importance of a multidisciplinary approach in order to improve outcomes. Management of COPD needs a systemic holistic approach that does not neglect the nonrespiratory component of treatment.

Given the potential complications of treatment and the interactions between comorbid diseases and COPD, some researchers have started to advocate for an integrated care approach to the management of patients with COPD. There is a need for a chronic care model approach to the management of COPD, including automatic screening for common comorbidities.

In order to truly build such a chronic care model, future research has to be moved in certain directions: including patients with comorbid conditions in clinical trials with appropriate analytic strategies to understand the heterogeneity of the treatment effect; investigating the development of a method for assessing and scoring comorbidities so that we can provide accurate prognostic information for patients as well as treat in a robust effective manner; evaluating current treatment regimens in patients with different patterns of comorbid conditions; and continuing to study possible pathophysiological connections between COPD and comorbidities.

Conclusion

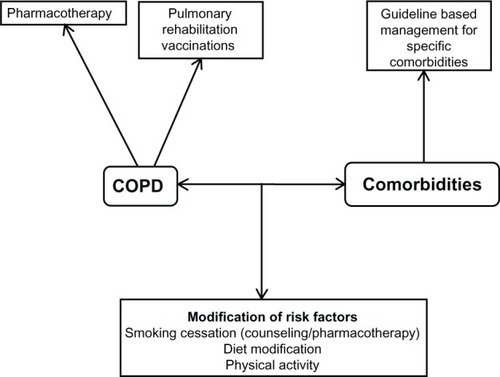

Management and medical intervention in COPD patients with comorbidities needs a holistic approach (), that is not clearly established in guidelines worldwide regarding the management of major chronic diseases. This holistic approach includes COPD management based on pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment, guideline-based management for specific comorbidities, and modification of the risk factors for COPD and comorbidities.

Figure 3 A holistic approach to medical intervention.

All health care specialists in COPD management need to work together with professionals specialized in the management of other major chronic diseases in order to provide a multidisciplinary treatment strategy for COPD patients with comorbidities. More studies are needed to clarify and establish a holistic approach to medical intervention in comorbid COPD patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- World Health OrganizationChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)2011 Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copdAccessed September 25, 2014

- ChatilaWMThomashowBMMinaiOACrinerGJMakeBJComorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc20085454955518453370

- TsiligianniIGKosmasEVan der MolenTTzanakisNManaging comorbidity in COPD: a difficult taskCurr Drug Targets201314215817623256716

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Revised2014 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed September 14, 2014

- KoskelaJKilpeläinenMKupiainenHCo-morbidities are the key nominators of the health related quality of life in mild and moderate COPDBMC Pulm Med201414110224946786

- ValderasJMStarfieldBSibbaldBSalisburyCRolandMDefining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health servicesAnn Fam Med20097435736319597174

- BowerPMacdonaldWHarknessEMultiborbidity, service organization and clinical decision making in primary care: a qualitative studyFam Pract201128557958721613378

- MacNeeWSystemic inflammatory biomarkers and co-morbidities of chronic obstructive diseaseAnn Med201345329130023110517

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPComorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186215516122561964

- CorsonelloAAntonelli IncalziRPistelliRPedoneCBustacchiniSLattanzioFComorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCurr Opin Pulm Med201117Suppl 1S21S2822209926

- SorianoJBVisickGTMuellerovaHPayvandiNHansellALPatterns of comorbidities in newly diagnosed COPD and asthma in primary careChest200512842099210716236861

- FuJJMcDonaldVMGibsonPGSimpsonJLSystemic inflammation in older adults with asthma-COPD overlap syndromeAllergy Asthma Immunol Res20146431632424991455

- MarshSETraversJWeatherallMProportional classifications of COPD phenotypesThorax200863976176718728201

- GibsonPGSimpsonJLThe overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it?Thorax200964872877519638566

- HardinMSilvermanEKBarrRGCOPDGene InvestigatorsThe clinical features of the overlap between COPD and asthmaRespir Res20111212721951550

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2008359151543155418836213

- TashkinDPCelliBDecramerMBronchodilator responsiveness in patients with COPDEur Respir J200831474275018256071

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- Global Initiative for AsthmaDiagnosis of diseases of chronic airflow limitation: asthma COPD and asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/AsthmaCOPDOverlap.pdfAccessed September 14, 2014

- KiriVASorianoJVisickGFabbriLRecent trends in lung cancer and its association with COPD: an analysis using the UK GP Research DatabasePrim Care Respir J2010191576119756330

- TammemagiCMNeslund-DudasCSimoffMKvalePImpact of comorbidity on lung cancer survivalInt J Cancer2003103679280212516101

- LoganathanRSStoverDEShiWVenkatramanEPrevalence of COPD in women compared to men around the time of diagnosis of primary lung cancerChest200612951305131216685023

- YoungRPHopkinsRJChristmasTBlackPNMetcalfPGambleGDCOPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking historyEur Respir J200934238038619196816

- CavaillèsABrinchault-RabinGDixmierAComorbidities of COPDEur Respir Rev20132213045447524293462

- SinDDAnthonisenNRSorianoJBAgustiAGMortality in COPD: the role of comorbiditiesEur Respir J20062861245125717138679

- AnthonisenNRSkeansMAWiseRAManfredaJKannerREConnettJELung Health Study Research GroupThe effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality: a randomized clinical trialAnn Intern Med2005142423323915710956

- Garcia-AymerichJFarreroEFelezMARisk factors of readmission to hospital for a COPD exacerbation: a prospective studyThorax200358210010512554887

- WashkoGRHunninghakeGMFernanzezIECOPDGene InvestigatorsLung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalitiesN Engl J Med20113641089790621388308

- SchonhoferBWenzelMGeibelMKöhlerDBlood transfusion and lung function in chronically anemic patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCrit Care Med19982611182418289824074

- MillerJEdwardsLDAgustíAEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) InvestigatorsComorbidity, systemic inflammation and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Med201310791376138423791463

- ErikssonBLindbergAMuellerovaHRönmarkELundbäckBAssociation of heart diseases with COPD and restrictive lung function – results from a population surveyRespir Med201310719810623127573

- Le JemtelTHPadelettiMJelicSDiagnostic and therapeutic challenges in patients with coexistent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failureAm J Coll Cardiol2007492171180

- RuttenFHCramerMJLammersJWGrobbeeDEHoesAWHeart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an ignored combination?Eur J Heart Fail200687707711

- SidneySSorelMQuesenberryCPJrDeLuiseCLanesSEisnerMDCOPD and incident cardiovascular disease. Hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser Permanente Medical Care ProgramChest200512842068207516236856

- Garcia-RodriguezLAWallanderMAMartin-MerinoEJohanssonSHeart failure, myocardial infarction, lung cancer and death in COPD patients: a UK primary care studyRespir Med2010104111691169920483577

- MascarenhasJLourencoPLopesRAzevedoABettencourtPChronic obstructive pulmonary disease in heart failure. Prevalence, therapeutic and prognostic implicationsAm Heart J2008155352152518294490

- FranssenFMRochesterCLComorbidities in patients with COPD and pulmonary rehabilitation: do they matter?Eur Respir Rev20142313113114124591670

- RuttenFHVonkenEJCramerMJCardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging to identify left-sided chronic heart failure in stable patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm Heart J2008156350651218760133

- SinDDManSFChronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortalityProc Am Thorac Soc20052181116113462

- BrekkePHOmlandTSmithPSøysethVUnderdiagnosis of myocardial infarction in COPD – Cardiac Infarction Injury Score (CIIS) in patients hospitalised for COPD exacerbationRespir Med200810291243124718595681

- SinDDManSFWhy are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCirculation2003107111514151912654609

- HuangBYangYZhuJClinical characteristics and prognostic significance of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with atrial fibrillation: results from a multicenter atrial fibrillation registry studyJ Am Med Dir Assoc201415857658124894999

- KonecnyTParkJYSomersKRRelation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to atrial and ventricular arrhythmiasAm J Cardiol2014114227227724878126

- LiJAgarwalSKAlonsoAAirflow obstruction, lung function, and incidence of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) studyCirculation2014129997198024344084

- Zoni-BerissoMLercariFCarazzaTDomenicucciSEpidemiology of atrial fibrillation: European perspectiveClin Epidemiol2014621322024966695

- GulsvikAHansteenVSivertssenECardiac arrhythmias in patients with serious pulmonary diseasesSand J Respir Dis1978593154159

- HayashiTFukamizuSHojoRPrevalence and electrophysiological characteristics of typical atrial flutter in patients with atrial fibrillation and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEuropace201315121777178323787904

- ChaouatANaeijeRWeitzenblumEPulmonary hypertension in COPDEur Respir J20083251371138518978137

- ChaouatABugnetASKadaouiNSevere pulmonary hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005172218919415831842

- JyothulaSSafdarZUpdate on pulmonary hypertension complicating chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009435136319802350

- WeitzenblumESautegeauAEhrhartMMammosserMPelletierALong-term oxygen therapy can reverse the progression of pulmonary hypertension in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm Rev Respir Dis198513144934983922267

- Tillie-LeblondIMarquetteCHPerezTPulmonary embolism in patients with unexplained exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence and risk factorsAnn Intern Med2006144639039616549851

- GunenHGulbasGInEYetkinOHacievliyagilSSVenous thromboemboli and exacerbations of COPDEur Respir J20103561243124819926740

- ChenWJLinCCLinCYPulmonary embolism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort studyCOPD201411443844325010753

- PeinadoVIBarberaJARamirezJEndothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arteries of patients with mild COPDAm J Physiol19982746 Pt 1908913

- BarrRGMesia-VelaSAustinJHImpaired flow-mediated dilation is associated with low pulmonary function and emphysema in ex-smokers: the Emphysema and Cancer Action Project (EMCAP) StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176121200120717761614

- SabitRThomasPShaleDJCollinsPLinnaneSJThe effects of hypoxia on markers of coagulation and systemic inflammation in patients with COPDChest20101381475120154074

- UndasAKaczmarekPSladekKFibrin clot properties are altered in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Beneficial effects of simvastatin treatmentThromb Haemost200910261176118219967149

- DoehnerWHaeuslerKGEndresMAnkerSDMacNeeWLainscakMNeurological and endocrinological disorders: orphans in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med2011105Suppl 11219

- VaidyulaVRCrinerGJGrabianowskiCRaoAKCirculating tissue factor procoagulant activity is elevated in stable moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThromb Res2009124325926119162305

- HozawaABillingsJLShaharEOhiraTRosamondWDFolsomARLung function and ischemic stroke incidence: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities studyChest200613061642164917166977

- FinkelsteinJChaEScharfSMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidityInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009433734919802349

- McGarveyLPJohnMAndersonJAZvarichMWiseRATORCH Clinical Endpoint CommitteeAscertainment of cause-specific mortality in COPD: operations of the TORCH Clinical Endpoint CommitteeThorax200762541141517311843

- CrisafulliECostiSLuppiFRole of comorbidities in a cohort of patients with COPD undergoing pulmonary rehabilitationThorax200863648749218203818

- CazzolaMBettoncelliGSessaECricelliCBiscioneGPrevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration201080211211920134148

- ManninoDMThornDSwensenAHolguinFPrevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPDEur Respir J200832496296918579551

- SongYKlevakAMansonJEBuringJELiuSAsthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and type 2 diabetes in the Women’s Health StudyDiabetes Res Clin Pract201090336537120926152

- EhrlichSFQuesenberryCPJrVan Den EedenSKShanJFerraraAPatients diagnosed with diabetes are at increased risk for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, and pneumonia but not lung cancerDiabetes Care2010331556019808918

- FearyJRRodriguesLCSmithCJHubbardRBGibsonJPrevalence of major comorbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke: a comprehensive analysis using data from primary careThorax2010651195696220871122

- TkacovaRSystemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: may adipose tissue play a role? Review of the literature and future perspectivesMediators Inflamm2010201058598920414465

- FabbriLMLuppiFBeghéBRabeKFComplex chronic comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J200831120421218166598

- Emerging Risk Factors CollaborationSeshasaiSRKaptogeSThompsonADiabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific deathN Engl J Med2011364982984121366474

- BakerEHJanawayCHPhilipsBJHyperglycaemia is associated with poor outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax200661428428916449265

- ParappilADepczynskiBCollettPMarksGBEffect of comorbid diabetes on length of stay and risk of death in patients admitted with acute exacerbations of COPDRespirology201015691892220546185

- WatanabeRTanakaTAitaKOsteoporosis is highly prevalent in Japanese males with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and is associated with deteriorated pulmonary functionJ Bone Miner Metab752014 [Epub ahead of print.]

- FergusonGTCalverleyPMAndersonJAPrevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the Towards a Revolution in COPD Health StudyChest200913661456146519581353

- Graat-VerboomLWoutersEFSmeenkFWvan den BorneBELundeRSpruitMACurrent status of research on osteoporosis in COPD: a systematic reviewEur Respir J200934120921819567604

- JanssensWBouillonRClaesBVitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in COPD and correlates with variants in the vitamin D-binding geneThorax201065321522019996341

- MaggiSSivieroPGonnelliSEOLO Study GroupOsteoporosis risk in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the EOLO studyJ Clin Densitom200912334535219647671

- ScanlonPDConnettJEWiseRALung Health Study Research GroupLoss of bone density with inhaled triamcinolone in Lung Health Study IIAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004170121302130915374846

- AgustiASorianoJBCOPD as a systemic diseaseCOPD20085213313818415812

- RuttenEPBreyerMKSpruitMAAbdominal fat mass contributes to the systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseClin Nutr201029675676020566396

- SeymourJMSpruitMAHopkinsonNSThe prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD and the relationship with disease severityEur Respir J2010361818819897554

- CielenNMaesKGayan-RamirezGMusculoskeletal disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBiomed Res Int2014201496576424783225

- DecramerMJanssensWMiravitllesMChronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLancet201237998231341135122314182

- EngelenMPScholsAMDoesJDWoutersEFSkeletal muscle weakness is associated with wasting of extremity fat-free mass but not with airflow obstruction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Clin Nutr200071373373810702166

- [No authors listed]Skeletal muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A statement of the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory SocietyAm J Respir Crit Care Med19991594 Pt 21409872811

- KunikMERoundyKVeazeyCSurprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disordersChest200512741205121115821196

- BarrRGCelliBRManninoDMComorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPDAm J Med2009122434835519332230

- NorwoodRPrevalence and impact of depression in chronic obstructive disease patientsCurr Opin Pulm Med200612211311716456380

- PoolerABeechRExamining the relationship between anxiety and depression and exacerbations of COPD which result in hospital admission: a systematic reviewInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014931533024729698

- SpitzerCGläserSGrabeHJMental health problems, obstructive lung disease and lung function: findings from the general populationJ Psychosom Res201171317417921843753

- RegvatJZmitekAVegnutiMKošnikMŠuškovičSAnxiety and depression during hospital treatment of exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Int Med Res20113931028103821819737

- AbramsTEVaughan-SarrazinMVan der WegMWAcute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the effect of existing psychiatric comorbidity on subsequent mortalityPsychosomatics201152544144921907063

- LaurinCLavoieKLBaconSLSex differences in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and psychological distress in patients with COPDChest2007132114815517505033

- Paz-DiazHMontes de OcaMLopezJMCelliBRPulmonary rehabilitation improves depression, anxiety, dyspnea and health status in patients with COPDAm J Phys Med Rehabil2007861303617304686

- SchneiderCJickSSBothnerUMeierCRCOPD and the risk of depressionChest2010137234134719801582

- Al-shairKDockryRMallia-MilanesBKolsumUSinghDVestboJDepression and its relationship with poor exercise capacity, BODE index and muscle wasting in COPDRespir Med2009103101572157919560330

- OmachiTAKatzPPYelinEHDepression and health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Med20091128778. e9e1519635280

- DiMatteoMRLepperHSCroghanTWDepression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherenceArch Intern Med2000160142101210710904452

- XuWColletJPShapiroSIndependent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178991392018755925

- JenningsJHDigiovineBObeidDFrankCThe association between depressive symptoms and acute exacerbations of COPDLung2009187212813519198940

- NgTPNitiMTanWCCaoZOngKCEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med20071671606717210879

- YohannesAMBalwinRCConnollyMJPrevalence of sub-threshold depression in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200318541261612766917

- QianJSimoni-WastilaLLangenbergPEffects of depression diagnosis and antidepressant treatment on mortality in Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Am Geriatr Soc201361575476123617752

- KrachmanSMinaiOAScharfSMSleep abnormalities and treatment in emphysemaProc Am Thorac Soc20085453654218453368

- MachadoMCVollmerWMTogeiroSMCPAP and survival in moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome and hypoxaemic COPDEur Respir J201035113213719574323

- MarinJMSorianoJBCarrizoSJBoldovaACelliBROutcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: the overlap syndromeAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182332533120378728

- McNicholasWTChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: overlaps in pathophysiology, systemic inflammation, and cardiovascular diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009180869270019628778

- VestboJHurdSSAgustíAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- TeradaKMuroSSatoSImpact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms on COPD exacerbationThorax2008631195195518535116

- KempainenRRSavikKWhelanTPDunitzJMHerringtonCSBillingsJLHigh prevalence of proximal and distal gastroesophageal reflux disease in advanced COPDChest200713161666167117400682

- MokhlesiBMorrisALHuangCFCurcioAJBarrettTAKampDWIncreased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in patients with COPDChest200111941043104811296167

- Rascon-AguilarIEPamerMWludykaPRole of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in exacerbations of COPDChest200613041096110117035443

- MapelDWMartonJPPrevalence of renal and hepatobiliary disease, laboratory abnormalities, and potentially toxic medication exposures among persons with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2013812713423515180

- ChenCYHsuTWMaoSJAbnormal renal resistive index in patients with mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCOPD201310221622523547633

- IncalziRACorsonelloAPedoneCBattagliaSPaglinoGBelliaVExtrapulmonary Consequences of COPD in the Elderly Study InvestigatorsChronic renal failure: a neglected comorbidity of COPDChest2010137483183719903974

- GjerdeBBakkePSUelandTHardieJAEaganTMThe prevalence of undiagnosed renal failure in a cohort of COPD patients in western NorwayRespir Med2012106336136622129490

- BarnesPJChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects beyond the lungsPLoS Med201073e100022020305715

- FletcherMJUptonJTaylor-FishwickJCOPD uncovered: an international survey on the impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] on a working age populationBMC Public Health20111161221806798

- YoungRPWhittingtonCFHopkinsRJChromosome 4q31 locus in COPD is also associated with lung cancerEur Respir J20103661375138221119205

- YoungRPHopkinsRJHayBAEptonMJBlackPNGambleGDLung cancer gene associated with COPD: triple whammy or possible confounding effect?Eur Respir J20083251158116418978134

- HanssonGKInflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery diseaseN Engl J Med200535261685169515843671

- EickhoffPValipourAKissDDeterminants of systemic vascular function in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178121211121818836149

- MirrakhimovAEChronic obstructive pulmonary disease and glucose metabolism: a bitter sweet symphonyCardiovasc Diabetol20121113223101436

- BarnesPJCelliBRSystemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20093351165118519407051

- FabbriLMRabeKFFrom COPD to chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome?Lancet2007370958979779917765529

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBCardiovascular events in patients with COPD: TORCH study resultsThorax201065871972520685748

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- WedzichaJACaverleyPMSeemungalTAHaganGAnsariZStockleyRAINSPIRE InvestigatorsThe prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromideAm J Respir Crit Care Med20081771192617916806

- BarrRGBourbeauJCamargoCAJrRamFSInhaled tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysisThorax2006611085486216844726

- ValenteSPasciutoGBernabeiRCorboGMDo we need different treatments for very elderly COPD patients?Respiration201080535736820733280

- PasqualeMKSunSXSongFHartnettHJStemkowskiSAImpact of exacerbations on health care cost and resource utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with chronic bronchitis from a predominantly Medicare populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012775776423152680

- OrnekTTorMAltinRClinical factors affecting the direct cost of patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Med Sci20129428529022701335

- PatelJGNagarSPDalalAAIndirect costs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review of the economic burden on employers and individuals in the United StatesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014928930024672234

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood InstituteMorbidity and Mortality 2009: Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung and Blood DiseasesBethesda, MD, USANational Institutes of Health2009

- HalpinDMMiravitllesMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the disease and its burden to societyProc Am Thorac Soc20063761962316963544

- MapelDWHurleyJSFrostFJPetersenHVPicchiMACoultasDBHealth care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A case-control study in a health maintenance organizationArch Intern Med2000160172653265810999980

- Simon-TuvalTScharfSMMaimonNBernhard-ScharfBJReuveniHTarasiukADeterminants of elevated healthcare utilization in patients with COPDRespir Res201112721232087

- ManninoDMWattGHoleDThe natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200627362764316507865

- DoosLUttleyJOnyiaIIqbalZJonesPWKadamUTMosaic segmentation, COPD and CHF multimorbidity and hospital admission costs: a clinical linkage studyJ Public Health (Oxf)201436231732423903003

- DarnellKDwivediAKWengZPanosRJDisproportionate utilization of healthcare resources among veterans with COPD: a retrospective analysis of factors associated with COPD healthcare costCost Eff Resour Alloc2013111323763761

- HillemanDDewanNMaleskerMFriedmanMPharmacoeconomic evaluation of COPDChest200011851278128511083675

- TeoWTanWSChongWEconomic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology201217112012621954985

- SharafkhanehAPetersenNYuHJDalalAAJohnsonMLHananiaNABurden of COPD in a government health care system: a retrospective observational study using data from the US Veterans Affairs populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010512513220461144

- FumagalliGFabianiFForteSINDACO project: a pilot study on incidence of comorbidities in COPD patients referred to pneumology unitsMultidiscip Respir Med2013812823551874

- GiardinoNDCurtisJLAndreiACNETT Research GroupAnxiety is associated with diminished exercise performance and quality of life in severe emphysema: a cross-sectional studyRespir Res2010112920214820

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerEWAdded value of co-morbidity in predicting health-related quality of life in COPD patientsRespir Med200195649650411421508

- MiyazakiMNakamuraHChubachiSKeio COPD Comorbidity Research (K-CCR) GroupAnalysis of comorbid factors that increase the COPD assessment test scoresRespir Res2014151324502760

- HallSFA user’s guide to selecting a comorbidity index for clinical researchJ Clin Epidemiol200659884985516828679

- CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCRA new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validationJ Chronic Dis19874053733383558716

- FreiAMuggensturmPPutchaNFive comorbidities reflected the health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the newly developed COMCOLD indexJ Clin Epidemiol201467890491124786594

- HawkinsNMPetrieMCMacdonaldMRHeart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the quandary of beta-blockers and beta-agonistsJ Am Coll Cardiol201157212127213821596228

- CelliBDecramerMLeimerIVogelUKestenSTashkinDPCardiovascular safety of tiotropium in patients with COPDChest20101371203019592475

- McMurrayJJAdamopoulosSAnkerSDESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESCEur Heart J201233141787184722611136

- Van der HooftCSHeeringaJBrusselleGGCorticosteroids and the risk of atrial fibrillationArch Intern Med200616691016102016682576

- WaltersJAWaltersEHWood-BakerROral corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20053CD00537416034972

- HuertaCLanesSFGarcia RodriguezLARespiratory medications and the risk of cardiac arrhythmiasEpidemiology200516336036615824553

- PageCCazzolaMBifunctional drugs for the treatment of asthma and obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J201444247548224696121

- LeeDSMarkwardtSMcAvayGJEffect of β-blockers on cardiac and pulmonary events and death in older adults with cardiovascular disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Care20145234551

- ForesiACavigioliGSignorelliGPozzoniMBOlivieriDIs the use of beta-blockers in COPD still an unresolved dilemma?Respiration201080317718720639691

- MateraMGMartuscelliECazzolaMPharmacological modulation of beta-adrenoceptor function in patients with coexisting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failurePulm Pharmacol Ther20102311819833222

- GottliebSSMcCarterRJVogelRAEffect of beta-blockade on mortality among high-risk and low-risk patients after myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med199833984894979709041

- PetersenHSoodAMeekPMRapid lung function decline in smokers is a risk factor for COPD and is attenuated by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor useChest2014145469570324008986

- ForthRMontgomeryHACE in COPDQ a therapeutic target?Thorax200358755655812832663

- ReinerZCatapanoALDe BackerGESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) 2008–2010 and 2010–2012 CommitteesESC/EAS Guidelines for the managements of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the managements of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS)Eur Heart J201132141769181821712404

- CorsonelloAPedoneCCoricaFGruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell’Anziano (GIFA) InvestigatorsConcealed renal insufficiency and adverse drug reactions in elderly hospitalized patientsArch Intern Med2005165779079515824299

- TanKHDe CossartLEdwardsPRExercise training and peripheral vascular diseaseBr J Surg200087555356210792309

- BennellKLHinmanRSA review of the clinical evidence for exercise in osteoarthritis of the hip and kneeJ Sci Med Sport20111414920851051

- O’GormanDJKrookAExercise and the treatment of diabetes and obesityMed Clin North Am201195595396921855702

- ThomasDEElliottEJNaughtonGAExercise for type 2 diabetes mellitusCochrane Database Syst Rev20063CD00296816855995

- MakeBDutroMPPaulose-RamRMartonJPMapelDWUndertreatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201271922315517

- BlanchetteCMGrossNJAltmanPRising costs of COPD and potential maintenance therapy to slow the trendAm Health Drug Benefits2014729810624991394

- AnecchinoCRossiEFanizzaCDe RosaMTognoniGRomeroMWorking Group ARNO ProjectPrevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pattern of comorbidities in a general populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20072456757418268930

- Lopez VarelaMVMontes de OcaMHalbertRJPLATINO TeamSex-related differences in COPD in five Latin American cities: the PLATINO studyEur Respir J20103651034104120378599

- van ManenJGBindelsPJLizermansCJvan der ZeeJSBottemaBJSchadéEPrevalence of comorbidity in patients with chronic airway obstruction and controls over the age of 40J Clin Epidemiol200154328729311223326