Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), one of the most common chronic diseases and a leading cause of death, has historically been considered a disease of men. However, there has been a rapid increase in the prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of COPD in women over the last two decades. This has largely been attributed to historical increases in tobacco consumption among women. But the influence of sex on COPD is complex and involves several other factors, including differential susceptibility to the effects of tobacco, anatomic, hormonal, and behavioral differences, and differential response to therapy. Interestingly, nonsmokers with COPD are more likely to be women. In addition, women with COPD are more likely to have a chronic bronchitis phenotype, suffer from less cardiovascular comorbidity, have more concomitant depression and osteoporosis, and have a better outcome with acute exacerbations. Women historically have had lower mortality with COPD, but this is changing as well. There are also differences in how men and women respond to different therapies. Despite the changing face of COPD, care providers continue to harbor a sex bias, leading to underdiagnosis and delayed diagnosis of COPD in women. In this review, we present the current knowledge on the influence of sex on COPD risk factors, epidemiology, diagnosis, comorbidities, treatment, and outcomes, and how this knowledge may be applied to improve clinical practices and advance research.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most common chronic conditions worldwide, and is now the third-leading cause of death in the US.Citation1 Over the past 20 years, COPD-related measures, including prevalence and mortality, have increased more rapidly among women than among men, altering the historical perception that COPD is predominantly a disease of men.Citation2 These changes have historically been attributed to the changes in smoking over the last century. Recent evidence suggests that men and women differ in their susceptibility to COPD risk factors,Citation3 possibly related to biologic and hormonal mechanisms. In addition, the clinical presentation of COPD, comorbidities, and other factors vary between sexes and may influence response to treatment. We summarize data on how sex influences risk factors, epidemiology, clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes of COPD, and how this knowledge may help us develop better management strategies.

Sex differences in risk factors of COPD

is a summary of the differences seen in COPD-related risk factors between men and women.

Table 1 Summary of the influence of sex on COPD risk factors

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is the most important risk factor for COPD in the developed world. COPD related to tobacco consumption increased over the past 100 years in most of the developed world as large numbers of men, then women, took up smoking. In the US, cigarette smoking peaked during the 1970s among men and during the 1980s among women. In the developing world, the prevalence of smoking among women is predicted to increase to 20% by 2025.Citation5 Future trends in COPD will reflect this change.

Men and women may have differential susceptibility to tobacco smoke. Women develop more severe COPD at younger ages than men and with lower levels of cigarette exposure.Citation6 In the NETT (National Emphysema Treatment Trial) study, women had fewer pack-years of cigarette smoking than men, but had similarly severe COPD.Citation7 A 2006 meta-analysis of smoking and COPD by Gan et al found that female smokers had a faster annual decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) than male smokers.Citation8 Moreover, Sørheim et al observed that among people with COPD younger than age 60 years, women had a lower mean FEV1 and more severe COPD with less cigarette-smoking exposure.Citation9 In that study, women had greater reductions in FEV1 than men when they had fewer than 20 pack-years of exposure, but after 25 pack-years of smoking, the dose–response relationship of men and women was similar.

The heightened susceptibility to cigarette smoke in women could have several etiologies. First, there may be a genetic predisposition for smoking-related lung damage in certain families that is sex-specific. Silverman et al found a very high prevalence of COPD among women (71.4%) in a study of 84 probands with severe early onset COPD. In addition, smoking female first-degree relatives of these probands were nearly twice as likely to have airway obstruction and 3.5 times as likely to have severe obstruction than smoking male relatives.Citation10 Second, women may have an increased dose-dependent tobacco susceptibility. Women have smaller lungs and airways than men; therefore, the same amount of tobacco smoke results in greater exposure. Furthermore, exposure to secondhand smoke and male/female differences in cigarette-brand preference and inhalational techniques may also be a factor.Citation11 Third, there may be hormonally mediated differences in tobacco-smoke metabolism. For example, animal studies demonstrate that cytochrome P450 enzymes are upregulated by estradiol, potentially making female lungs more susceptible to cigarette smoke-related oxidant.Citation12

Occupational exposure

Chronic exposure to occupational dusts is a risk factor for the spectrum of chronic respiratory diseases.Citation13 Common occupational exposures linked to COPD include those that come from mining (coal, heavy metals), agriculture (organic dusts), and other industries (metallic fumes like cadmium and aluminum).Citation14 These occupations have classically been held by men. However, with the reassignment of sex roles and more single-parent families, a higher number of women are filling those historically male-held jobs. In addition, women, especially in the developing world, are working in other dusty industries like the production of textiles, brassware, ceramics, and glassware.

Nonoccupational exposure

Although air-pollution levels have been decreasing in many parts of the world, these levels remain elevated in some countries like the People’s Republic of China and India. This is of particular significance, as recent data suggest that girls experience more reduction in pulmonary function than boys when they have exposure to either environmental air pollution or tobacco smoke.Citation15

In addition, indoor air pollution disproportionately affects women, particularly in the developing world. This is primarily due to the common practice of using unprocessed solid fuels, such as wood and dung, for cooking and heating and the reality that cooking is often a task done exclusively by women.Citation16

Asthma

Asthma is a common comorbidity, as well as a risk factor for COPD. People with asthma are at much higher risk of having COPD.Citation17 A longitudinal study by Silva et al found that compared to nonasthmatics, active asthmatics had a tenfold-higher risk for acquiring symptoms of chronic bronchitis, a 17-fold higher risk of receiving a diagnosis of emphysema, and a 12-fold higher risk of having COPD, even after adjusting for smoking history and other potential confounders.Citation18

The influence of sex on asthma has been studied extensively. Studies show an increased incidence and prevalence of asthma in women, and that asthmatic women have a lower quality of life (QoL) and more utilization of health care compared to their male counterparts, despite similar medical treatment and lung function.Citation19 Researchers continue to study the reasons for these differences, including the potential affect of sex hormones, differential perception of airflow obstruction, atopy, heightened bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and medication compliance and technique. The relationship is likely a complex one involving all those factors.

Genetics

Genetics plays an important role in the development of COPD. The most well-known genetic factor in the development of COPD is the deficiency of the enzyme α1-antitrypsin. However, there are a number of other genes that are likely involved in the pathogenesis of COPD. Foreman et al analyzed data from 2,500 subjects in the COPDGene study, a large study that enrolled smokers with and without COPD at 21 clinical centers throughout the US.Citation20 Severe, early onset COPD participants were overwhelmingly female (66%), with higher rates among African American smokers. The COPDGene study has a longitudinal component that will provide new insights into the biologic and sex differences in the genetic predictors of COPD development and progression.

Infections

Bacterial and viral infections are a major cause of acute exacerbations of COPD, and contribute to the development and progression of COPD.Citation21 Sex may influence the development and outcomes of upper and lower respiratory infections, although this has not been studied extensively. An analysis of 84 published studies demonstrated that upper respiratory infections were more common in women, while lower respiratory infections were more common in men.Citation22 The same analysis demonstrated that the course of most respiratory infections is more severe in males, leading to higher mortality, especially with community-acquired pneumonia. Similar findings have been reported in other studies, as noted in the outcome sections to follow. The precise reasons behind these differences are not clear, although biologically and hormonally mediated variability in immunity and behavioral differences may be involved.

Sex differences in the prevalence of COPD

Sex influences COPD in a number of different ways. is a summary of these differences in prevalence, comorbidities, and response to different treatment modalities. The measurement and monitoring of the burden of COPD, despite its high prevalence, remains difficult. Prevalence estimates of COPD rely on a number of measures, including self-report, administrative databases, and lung-function testing. In general, higher prevalence is seen among men with analyses of administrative databases, while self-reports show higher prevalence among women.Citation23

Table 2 Summary of the influence of sex on the prevalence, diagnosis, and outcomes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

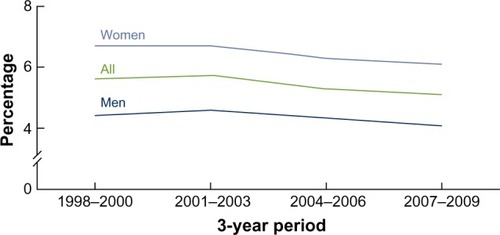

In the US, between the first and third National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), the prevalence of spirometrically determined COPD increased among women from 50.8 to 58.2 per 1,000, while the prevalence decreased among men from 108.1 to 74.3 per 1,000.Citation24 Findings from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that the self-reported prevalence of COPD (chronic bronchitis and emphysema) in the US did not change between 1998 and 2009, and has remained higher among women than among men ().Citation25 Similar patterns have been observed in other developed countries like Canada, Netherlands, and Austria.Citation26–Citation28 In the developing world, diagnosed COPD remains higher among men than among women;Citation29–Citation31 while some of these differences may reflect a sex bias in the diagnosis of COPD, the future will likely see increasing prevalence among women as more take up smoking and work in traditionally male occupations.Citation32

Figure 1 Prevalence of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over: US, 1998–2009.

Sex differences in the expression of COPD

There are also phenotypic differences between women and men in the expression of COPD, which might help explain some of the prevalence differences noted earlier. In 1987, Burrows et al suggested that sex dimorphism may be present in COPD when they described two types of COPD: emphysema and chronic asthmatic bronchitis.Citation33 People with emphysema were more likely to be men, experienced more rapid decline in pulmonary function, and had a higher mortality rate. People with chronic asthmatic bronchitis were more likely to be women, experienced less rapid decline in pulmonary function, and had a lower mortality rate. NHIS data similarly suggest that chronic bronchitis is more common among women, and emphysema is traditionally more common among men, although since 2011 more women in the US have been diagnosed with emphysema than men.Citation34 Radiologic and histologic data also show similar findings, with women having less severe emphysema but thicker airway walls and smaller airway lumens.Citation35

An interesting observation with regard to sex is seen in COPD among never-smokers. About 15%–30% of all people who have evidence of COPD are never-smokers. Of this group, nearly 80% are women, suggesting that women may be more susceptible to nonsmoking-related factors.Citation36 In one prospective study of COPD among never-smokers, sputum eosinophilia was elevated in one group and sputum neutrophil count was elevated in another.Citation37 The group with the neutrophilia had a higher prevalence of organ-specific autoimmune disease and autoantibodies, including thyroid disease. In another study, changes in the bronchoalveolar lavage-cell proteome were found in female but not male patients.Citation38 These observations suggest that increased responsiveness of the female immune system may be responsible for some sex-related differences.Citation39

Women who have COPD are more likely to report dyspneaCitation40,Citation41 and less likely to report the production of phlegm.Citation40,Citation42 In addition, women report higher intensity of dyspnea despite fewer pack-years of smoking and similar degrees of pulmonary impairment.Citation41 A recent Spanish study showed that women reported less phlegm than men but a similar level of cough, dyspnea, and wheezing.Citation43 An analysis of the PLATINO (Proyecto Latinoamericano de Investigación en Obstrucción Pulmonar) cohort showed that dyspnea was more common among women both with and without COPD.Citation44 In the ECLIPSE (Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints) cohort, when stratified by COPD-severity category, men and women had a similar age, but women had less smoking exposure, lower body mass index and fat-free mass index, and more exacerbations than men.Citation45 In the TORCH (Towards a Revolution for COPD Health) study, women reported more exacerbations and worse dyspnea.Citation46 The Euroscop study demonstrated that FEV1 as well as change over time correlated with prevalence, remission, and incidence of symptoms in men. This study suggests that symptoms are a good predictor of disease status and/or underlying disease activity, particularly among men.Citation47

The reasons behind differences in clinical expression of COPD between men and women are likely multifactorial. Becklake and Kauffmann suggested that societal concepts of athleticism may cause men to report less breathlessness than women;Citation48 others have suggested that sociocultural factors may result in women being less likely to report the production of sputum or phlegm.Citation23 Some physiologic data suggest that fat-free body mass, which is lower in women with COPD, is related to a lower diffusion capacity and more dyspnea.Citation49

Sex bias in the diagnosis of COPD

Health care providers are more likely to diagnose COPD in men than women. This has important implications in the care and outcome of these patients. Two studies assessed sex bias in the diagnosis of COPD among health care workers in recent years. In 2001 in the US and Canada, Chapman et al had a study publishedCitation50 that was replicated in Spain by Miravitlles et al in 2006.Citation51 The Confronting COPD Survey also found that after adjusting for age, pack-years, country, and dyspnea scores, women were less likely to have had spirometry but more likely to have had smoking-cessation advice.Citation40 In another recent study of more than 3,500 patients by Ancochea et al, 73% of patients with spirometric COPD criteria were underdiagnosed clinically, and this percentage varied by sex, being 30% more frequent among women (86.0%) than among men (67.6%).Citation43 Also, a study looking at the perception of COPD found that women were more likely to report COPD diagnostic delay, difficulty reaching the physician, and not being able to spend sufficient time with the physician.Citation52 Together, these data suggest that women with COPD are underdiagnosed and less likely to be controlled and content with their COPD treatment.

Sex differences in comorbidities

Patients with COPD often have coexisting medical conditions that contribute to morbidity and mortality. Although sex differences in comorbidities are relatively understudied, men and women differ in their patterns of comorbid diseases, which might explain, in part, the differences in outcomes between the two sexes. In the ECLIPSE cohort, cardiovascular comorbidity and diabetes were less common among women, whereas osteoporosis, inflammatory bowel disease, reflux, and depression requiring treatment were more common.Citation45 In a European study, women with COPD had less ischemic heart disease and alcoholism, but more chronic heart failure, osteoporosis, and diabetes mellitus.Citation53 A recent Swedish study of oxygen-dependent COPD patients showed that men had more arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, cancer and renal failure, fewer mental disorders, and less osteoporosis, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis than women.Citation54 Women also had more anxiety and depression and worse symptom-related QoL than men.Citation55,Citation56 Symptoms and QoL measures may be more important determinants of depression in women with COPD than physiologic and biologic measures.Citation57

Sex-related differences in treatment options for COPD

Smoking cessation

Smoking cessation is the only intervention documented to slow lung-function decline.Citation58 Women are not only more susceptible to adverse effects of tobacco smoking but also they may have more benefits upon successfully quitting smoking. This was demonstrated in the Lung Health Study that showed that women who remained nonsmokers had an average improvement in their FEV1 % predicted during the first year that was 2.5 times greater than the improvement seen in their male ounterparts.Citation59 However, women may have more difficulty quitting and have a lower long-term success rate of smoking cessation than men do; this may be, in part, due to less symptomatic benefit upon quitting among women.Citation32 Recent population data from the US, Canada and the UK suggest similar rates of successful tobacco cessation between sexes.Citation60 Older pharmacologic therapy with nicotine replacement was more beneficial among men, whereas the newer agents bupropion and varenicline seem to be equally effective in women and men.Citation32

Pharmacologic management of COPD

There are few data on sex differences in different therapies for COPD, because most studies of pharmacologic agents have not been designed to assess treatment in men versus women and most trials have enrolled more males than females.Citation3 For example, little is known about how differences in lung anatomy and physiology of males and females may affect dosage, delivery, and effectiveness of inhaled medications. Based on current studies, there is minimal known effect of sex on efficacy and adverse events of current agents. One study found no male/female differences in the efficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone combination therapy on predose FEV1, exacerbation rate, or QoL scores.Citation61 Another study demonstrated that the effects of tiotropium on lung function, symptoms, and QoL were similar in men and women.Citation62 Budesonide led to a reduction in phlegm among men but not women in the Euroscop study.Citation63,Citation64 The probability of respiratory deterioration (either symptomatic or exacerbations) when stopping inhaled steroids is higher among women than among men.Citation65 In a recent study of azithromycin for the prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD, a subgroup analysis showed a nonstatistical difference favoring women.Citation66 Large and better-designed trials are necessary to determine whether clinically meaningful sex differences exist in the pharmacotherapy of COPD.

There may also be sex differences in prescribing habits of providers, as well as compliance with medications between men and women. Dales et al found that among patients with mild-to-moderate COPD, the proportion of females on respiratory medications was twice that of males; this difference was not seen in severe COPD.Citation67 On the other hand, Sestini et al found that men with COPD were more likely than women to be on the “new” dry-powder inhalers versus metered-dose inhalers.Citation68

Long-term oxygen therapy

Long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) improves survival among hypoxemic patients with COPD, but the impact of sex on LTOT has been mixed. A meta-analysis of LTOT showed that women on LTOT had a survival advantage over men.Citation69 However, Machado et al reported that in a cohort of patients with COPD receiving LTOT, survival was significantly worse among women.Citation70 Discrepancies between these studies may be due to patient population and analytical approaches, and the criteria for indications to start LTOT.

Vaccination

Studies on sex differences in vaccination are scant. One study from Israel showed that women were less likely to receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations,Citation71 but it is not clear that this finding can be extrapolated to other countries and cultures.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

A multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation program should be part of the therapy of all patients with COPD, and should include components of exercise training, nutritional counseling, and patient education. Foy et al demonstrated that after 3 months of exercise therapy, both men and women reported similar improvements in health-related QoL (HRQoL) measures; after 18 months, however, continued benefits were seen in men but not in women.Citation72 Haggerty et al assessed improvements in outcomes among 164 subjects (54% female) in pulmonary rehabilitation.Citation73 They found that women experienced larger improvements in the mastery and emotion subscales of the Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRDQ) and the psychosocial subscale of the Pulmonary Function Status Scale (PFSS); however, all other outcomes (other subscales of the CRDQ and the PFSS, and 6-minute walk distance) were similar between men and women.

Influence of sex in outcomes of COPD

Differences in morbidity, acute exacerbations, and hospitalizations

COPD is a major source of morbidity globally. The difference in prevalence of COPD, diagnosis, comorbidities, and outcomes with treatment in the two sexes has been discussed in the prior sections. Females also have a decreased HRQoL related to COPD. In both the PLATINO and TORCH cohorts, more females identified their health as fair to poor compared to males, and currently smoking females had more severe disease than males.Citation44,Citation46 In addition, the factors determining HRQoL for men and women with COPD may differ by sex. In one study among men, the total SGRQ score was predicted by dyspnea, exercise capacity, degree of hyperinflation, and comorbidity, whereas among women the only predictors were dyspnea and oxygenation status.Citation74

Men and women differ in the outcomes of acute exacerbations and hospitalizations of COPD, with women generally having a survival advantage. In one study of COPD exacerbations in the emergency department, Cydulka et al found higher relapse rates among men despite similar levels of care provided in the hospital.Citation42 However, they also found that women were less likely to self-medicate with anticholinergic agents, and were less likely to seek emergency care within the first 24 hours of exacerbation. Cao et al found among 186 patients with COPD in Singapore that men had more hospital admissions in a year for COPD exacerbations than women.Citation75 In a recent analysis of over 40,000 people in Canada, Gonzalez et al found that men had an increased risk of death and hospitalization for COPD.Citation76 Patil and colleagues also found an increased risk for in-hospital mortality among men admitted for an acute exacerbation of COPD.Citation77

Differences in mortality

Between 1990 and 2010, COPD became the third-leading cause of death in the US. Death rates for COPD declined among US men between 1999 (57.0 per 100,000) and 2006 (46.4 per 100,000), whereas there was no significant change in death rates among women (35.3 per 100,000 in 1999 and 34.2 per 100,000 in 2006). In 2000, the absolute number of women dying from COPD surpassed the number of men, although the age-adjusted COPD death rates for men were 30% higher than those rates for women.Citation23 In 2009, de Torres et al showed that after controlling for disease severity, women had significantly better survival than men.Citation78

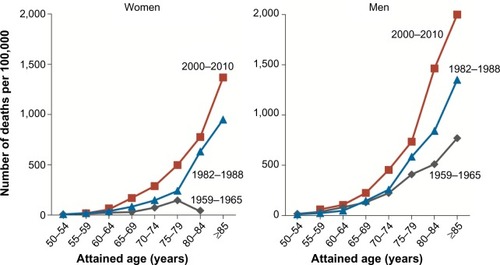

A recent assessment of changes in mortality rates due to COPD in the cohorts from NHANES I and NHANES III in the US showed a smaller decrease in the mortality rate among women with moderate or severe COPD than among men (3.0% versus 17.8%).Citation79 An analysis of smoking-related mortality in the US evaluated temporal trends in sex-specific smoking-related mortality across three time periods (1959–1965, 1982–1988, 2000–2010) in seven large cohorts.Citation80 In the “contemporary” cohort (2000–2010), male and female current smokers had similar relative risks for mortality from COPD (26.61 for men, 22.35 for women), with these relative risks representing almost a doubling of risk compared to the 1982–1988 time period (). The survival advantage that women with COPD have historically had has been slowly diminishing in recent years. Finally, in a recent analysis of the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) cohort, spirometric restriction was more predictive of increased mortality risk than airflow obstruction in both the sexes, with worse mortality seen in lower-income groups.Citation81

Figure 2 Changes in rates of death from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease over time among current female and male smokers in three time periods.

Conclusion

The influence of sex on COPD risk and outcomes is due to a combination of both environmental/behavioral factors and genetic/biophysiologic factors. In addition, the roles that women play in society, along with cultural norms and expectations, are changing rapidly in both the developed and developing worlds. Identifying the reasons and mechanisms behind those factors, as well as the sex differences in the pattern of comorbidities, exacerbations, and therapeutic response, may lead to improved therapies and outcomes.

Disclosure

DMM has served on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Sepracor, Astra-Zeneca, Novartis, and Ortho Biotech, and has received research grants from Astra-Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Pfizer. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MurphySLXuJKochanekKDDeaths: Final Data for 2010Nat Vital Stat Rep2013611117

- World Health OrganizationWorld Health Statistics: 2008GenevaWHO2008 Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/EN_WHS08_Full.pdfAccessed June 1, 2014

- US Department of Health and Human ServicesThe Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General – Executive SummaryRockville (MD)HSS2014 Available from: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/exec-summary.pdfAccessed June 2, 2014

- BurnsDMajorJShanksTChanges in number of cigarettes smoked per day: cross-sectional and birth cohort analyses using NHISRuppertWThose Who Continue to Smoke: Is Achieving Abstinence Harder and Do We Need to Change Our Interventions?Collingdale (PA)Diane20048399

- MackayJAmosAWomen and tobaccoRespirology2003812313012753525

- MurrayCJLopezADAlternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-202: Global Burden of Disease StudyLancet1997349149815049167458

- MartinezFJCurtisJLSciurbaFCSex differences in severe pulmonary emphysemaAm J Respir Crit Care Med200717624325217431226

- GanWQManSFPostmaDSCampPSinDDFemale smokers beyond the perimenopausal period are at increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisRespir Res200675216571126

- SørheimICJohannessenAGulsvikABakkePSSilvermanEKDeMeoDLGender differences in COPD: are women more susceptible to smoking effects than men?Thorax20106548048520522842

- SilvermanEWeissSDrazenJGender-related differences in severe, early-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001622152215811112130

- HanMKPostmaDManninoDGender and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: why it mattersAm J Respir Crit Care Med20071761179118417673696

- Van WinkleLSGundersonADShimizuJABakerGLBrownCDGender differences in naphthalene metabolism and naphthalene-induced acute lung injuryAm J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol2002282L1122L113411943679

- EisnerMDAnthonisenNCoultasDAn official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: Novel risk factors and the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med201018269371820802169

- Diaz-GuzmanEAryalSManninoDMOccupational chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an updateClin Chest Med20123362563623153605

- SinDDCohenSBDayACoxsonHParéPDUnderstanding the biological differences in susceptibility to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease between men and womenProc Am Thorac Soc2007467167418073400

- VarkeyABChronic obstructive pulmonary disease in women: exploring gender differencesCurr Opin Pulm Med2004109810315021178

- Diaz-GuzmanEManninoDMAirway obstructive diseases in older adults: from detection to treatmentJ Allergy Clin Immunol201012670270920920760

- SilvaGESherrillDLGuerraSBarbeeRAAsthma as a risk factor for COPD in a longitudinal studyChest2004126596515249443

- KynykJAMastronardeJGMcCallisterJWAsthma, the sex differenceCurr Opin Pulm Med20111761121045697

- ForemanMGZhangLMurphyJEarly-onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with female sex, maternal factors, and African American race in the COPDGene StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184441442021562134

- Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseBethesda (MD)GOLD2013

- FalagasMEMourtzoukouEGVardakasKZSex differences in the incidence and severity of respiratory tract infectionsRespir Med20071011845186317544265

- CampPGGoringSMGender and the diagnosis, management, and surveillance of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc2007468669118073404

- ManninoDMHomaDMAkinbamiLJFordESReddSCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance – United States, 1971–2000MMWR Surveill Summ200251116

- AkinbamiLJLiuXChronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998–20092011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db63.htmAccessed August 4, 2014

- GershonASWangCWiltonASRautRToTTrends in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence, incidence, and mortality in Ontario, Canada, 1996 to 2007: a population-based studyArch Intern Med201017056056520308643

- BischoffEWSchermerTRBorHBrownPvan WeelCvan den BoschWJTrends in COPD prevalence and exacerbation rates in Dutch primary careBr J Gen Pract20095992793319891824

- SchirnhoferLLamprechtBVollmerWMCOPD prevalence in Salzburg, Austria: results from the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) studyChest2007131293617218553

- MenezesAMPerez-PadillaRJardimJRChronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence studyLancet20053661875188116310554

- BhomeABCOPD in India: iceberg or volcano?J Thorac Dis2012429830922754670

- ZhongNWangCYaoWPrevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based surveyAm J Respir Crit Care Med200717675376017575095

- HanMKPostmaDManninoDGender and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: why it mattersAm J Respir Crit Care Med20071761179118417673696

- BurrowsBBoomJTraverGClineMThe course and prognosis of different forms of chronic airways obstruction in a sample from the general populationN Engl J Med1987317120912143657891

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionNational Center for Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey raw data2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2011_data_release.htmAccessed September 9, 2014

- MartinezFCurtisJSciurbaFSex differences in severe pulmonary emphysemaAm J Respir Crit Care Med200717624325217431226

- CelliBRHalbertRJNordykeRJCOPD in never smokers: a significant problem? Airway obstruction in never smokers: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyAm J Med20051181364137216378780

- BirringSBrightlingCBraddingPClinical, radiologic and induced sputum features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in nonsmokers: a descriptive studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med20021661078108312379551

- KohlerMSandbergAKjellqvistSGender differences in the bronchoalveolar lavage cell proteome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Allergy Clin Immunol201313174375123146379

- AryalSDiaz-GuzmanEManninoDMCOPD and gender differences: an updateTransl Res201316220821823684710

- WatsonLVestboJPostmaDSGender differences in the management and experience of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med2004981207121315588042

- de TorresJPCasanovaCHernándezCAbreuJAguirre-JaimeACelliBRGender and COPD in patients attending a pulmonary clinicChest20051282012201616236849

- CydulkaRKRoweBHClarkSEmermanCLRimmARCamargoCAGender differences in emergency department patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbationsAcad Emerg Med2005121173117916282511

- AncocheaJMiravitllesMGarcía-RíoFUnder-diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in women: quantification of the problem, determinants and proposed actionsArch Bronconeumol20134922322923317767

- Lopez VarelaMVMontes de OcaMHalbertRJSex-related differences in COPD in five Latin American cities: the PLATINO studyEur Respir J2010361034104120378599

- AgustiACalverleyPMCelliBCharacterization of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Res20101112220831787

- CelliBVestboJJenkinsCRSex differences in mortality and clinical expressions of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The TORCH experienceAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118331732220813884

- WatsonLVonkJMLofdahlCGPredictors of lung function and its decline in mild to moderate COPD in association with gender: results from the Euroscop studyRespir Med200610074675316199147

- BecklakeMRKauffmannFGender differences in airway behavior over the human life spanThorax1999541119113810567633

- VerhageTLHeijdraYMolemaJVercoulenJDekhuijzenRAssociations of muscle depletion with health status. Another gender difference in COPD?Clin Nutr20113033233821081257

- ChapmanKRTashkinDPPyeDJGender bias in the diagnosis of COPDChest20011191691169511399692

- MiravitllesMde la RozaCNaberanKAttitudes toward the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary careArch Bronconeumol20064238 Spanish16426516

- MartinezCHRaparlaSPlauschinatCAGender differences in symptoms and care delivery for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Womens Health (Larchmt)2012211267127423210491

- AlmagroPLópez GarcíaFCabreraFComorbidity and gender-related differences in patients hospitalized for COPD. The ECCO studyRespir Med201010425325919879744

- EkströmMPJogréusCStrömKEComorbidity and sex-related differences in mortality in oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePLoS One20127e3580622563405

- Di MarcoFVergaMReggenteMAnxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severityRespir Med20061001767177416531031

- GudmundssonGGislasonTJansonCRisk factors for rehospitalisation in COPD: role of health status, anxiety and depressionEur Respir J20052641441916135721

- HananiaNAMüllerovaHLocantoreNWDeterminants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118360461120889909

- PauwelsRABuistASMaPJenkinsCRHurdSSGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): executive summaryRespir Care20014679882511463370

- ScanlonPDConnettJEWallerLAAltoseMDBaileyWCBuistASSmoking cessation and lung function in mild-to-moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lung Health StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med200016138139010673175

- JarvisMJCohenJEDelnevoCDGiovinoGADispelling myths about gender differences in smoking cessation: population data from the USA, Canada and BritainTob Control20132235636022649182

- VestboJSorianoJBAndersonJACalverleyPPauwelsRJonesPGender does not influence the response to the combination of salmeterol and fluticasone propionate in COPDRespir Med2004981045105015526804

- O’DonnellDEFlügeTGerkenFEffects of tiotropium on lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in COPDEur Respir J20042383284015218994

- WatsonLSchoutenJPLofdahlCGPrideNBLaitinenLAPostmaDSPredictors of COPD symptoms: does the sex of the patient matter?Eur Respir J20062831131816707516

- HubbardRBSmithCJSmeethLHarrisonTWTattersfieldAEInhaled corticosteroids and hip fracture: a population-based case-control studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med20021661563156612406825

- SchermerTRHendriksAJChavannesNHProbability and determinants of relapse after discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with COPD treated in general practicePrim Care Respir J200413485516701637

- AlbertRKConnettJBaileyWCAzithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med201136568969821864166

- DalesREMehdizadehAAaronSDVandemheenKLClinchJSex differences in the clinical presentation and management of airflow obstructionEur Respir J20062831932216880366

- SestiniPCappielloVAlianiMPrescription bias and factors associated with improper use of inhalersJ Aerosol Med20061912713616796537

- CrockettAJCranstonJMMossJRAlpersJHSurvival on long-term oxygen therapy in chronic airflow limitation: from evidence to outcomes in the routine clinical settingIntern Med J20013144845411720057

- MachadoMCKrishnanJABuistSASex differences in survival of oxygen-dependent patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200617452452916778158

- SchwartzAWClarfieldAMDoucetteJDisparities in pneumococcal and influenza immunization among older adults in Israel: a cross-sectional analysis of socio-demographic barriers to vaccinationPrev Med20135633734023402962

- FoyCGRejeskiWJBerryMJZaccaroDWoodardCMGender moderates the effects of exercise therapy on health-related quality of life among COPD patientsChest2001119707611157586

- HaggertyMCStockdale-WoolleyRZuwallackRFunctional status in pulmonary rehabilitation participantsJ Cardiopulm Rehabil199919354210079419

- de Torres TajesJPCasanovaCHernándezCGender associated differences in determinants of quality of life in patients with COPD: a case series studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes200647217007639

- CaoZOngKCEngPTanWCNgTPFrequent hospital readmissions for acute exacerbation of COPD and their associated factorsRespirology20061118819516548905

- GonzalezAVSuissaSErnstPGender differences in survival following hospitalisation for COPDThorax201166384221113016

- PatilSPKrishnanJALechtzinMDDietteGBIn-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med20031631180118612767954

- de TorresJPCoteCLópezMVSex differences in mortality in patients with COPDEur Respir J20093352853519047315

- FordESManninoDMZhaoGLiCCroftJBChanges in mortality among US adults with COPD in two national cohorts recruited from 1971–1975 and 1988–1994Chest201214110111021700689

- ThunMJCarterBDFeskanichD50-year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United StatesN Engl J Med201336835136423343064

- BurneyPJithooAKatoBChronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality and prevalence: the associations with smoking and poverty – a BOLD analysisThorax20146946547324353008