Abstract

Background

The causal association between depression, anxiety, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is unclear. We therefore conducted a systematic review of prospective cohort studies that measured depression, anxiety, and HRQoL in COPD.

Methods

Electronic databases (Medline, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL], British Nursing Index and Archive, PsycINFO and Cochrane database) were searched from inception to June 18, 2013. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: used a nonexperimental prospective cohort design; included patients with a diagnosis of COPD confirmed by spirometry; and used validated measures of depression, anxiety, and HRQoL. Data were extracted and pooled using random effects models.

Results

Six studies were included in the systematic review; of these, three were included in the meta-analysis for depression and two were included for the meta-analysis for anxiety. Depression was significantly correlated with HRQoL at 1-year follow-up (pooled r=0.48, 95% confidence interval 0.37–0.57, P<0.001). Anxiety was also significantly correlated with HRQoL at 1-year follow-up (pooled r=0.36, 95% confidence interval 0.23–0.48, P<0.001).

Conclusion

Anxiety and depression predict HRQoL in COPD. However, this longitudinal analysis does not show cause and effect relationships between depression and anxiety and future HRQoL. Future studies should identify psychological predictors of poor HRQoL in well designed prospective cohorts with a view to isolating the mediating role played by anxiety disorder and depression.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is responsible for approximately 5% of deaths worldwide and is predicted to become the third leading cause of death by 2030.Citation1 It is a chronic respiratory disease that typically results in a wide range of extrapulmonary comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, skeletal muscle dysfunction, osteoporosis, diabetes, anemia, and depression.Citation2,Citation3 COPD severity has traditionally been assessed using measures of airflow obstruction, such as forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). However, the therapeutic focus in COPD has started to shift away from an emphasis on lung function and mortality to management of comorbidities and more patient-centered outcomes related to functioning and health status. This trend is reflected in the increased use and reliance on patient-centered outcomes such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) to assess the impact of therapeutic strategies in COPD.Citation4

HRQoL is a multidimensional concept that refers to quality of life that is directly related to health or illness. It often includes domains related to the physical, social, and psychological impact of illness.Citation5 HRQoL is concerned with a patient’s experience of illness and can be defined as the subjective perception of the impact of health status on satisfaction with daily life.Citation5–Citation7 COPD severity is associated with impaired HRQoL,Citation8–Citation10 but poor HRQoL can also exacerbate symptoms of COPD (such as breathlessness) and can have a significant impact on physical functioning, the probability of hospital admission, and mortality.Citation11–Citation18

There are a range of psychological factors that might explain variation in respiratory-specific HRQoL over and above markers of disease severity, such as FEV1. Depression and anxiety have both been found to be important predictors of HRQoL in cross-sectional studies,Citation19–Citation24 with anxiety explaining over 40% of the variance in HRQoL in some cases.Citation20 Tsiligianni et al conducted a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies and reported that depression and anxiety were highly correlated with respiratory-specific HRQoL; a higher correlation was only found between dyspnea and HRQoL.Citation25 Further studies conducted since this review have confirmed this finding,Citation26 with one population-based study in Singapore showing that the impact of depression on HRQoL in COPD was significantly greater than in people without COPD.Citation27 Some cross-sectional studies have also examined the association between psychological health and more generic measures of HRQoL, such as the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form.Citation28 However, even when HRQoL is measured using these generic measures, depression and anxiety still account for a significant proportion of the variance in people with COPD.Citation29,Citation30

Findings to date are thus mainly derived from cross-sectional studies, and although results suggest that there is a significant association between depression, anxiety, and HRQoL in COPD, they are not able to determine causal associations between these factors. It is important to consider the temporal and causal association between depression and/or anxiety and HRQoL in order to inform the development of future interventions aimed at improving HRQoL. We have therefore conducted a systematic review with meta-analysis of longitudinal prospective studies to assess the ability of depression and anxiety to predict future HRQoL in patients with COPD.

Methods

The methods and results for this review are reported in line with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.Citation31

Information sources and search strategy

Studies were identified for inclusion in this review by searching the following electronic databases from inception to June 18, 2013: Medline, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), British Nursing Index and Archive, PsycINFO, and Cochrane database. The search strategy was designed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and key words relating to COPD, depression, anxiety, panic, HRQoL, and longitudinal cohort studies for each database. Electronic searches were supplemented by hand searches of reference lists of included papers and relevant reviews.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in this review if they:

used a nonexperimental prospective cohort design

did not include any standardized experimental intervention; this was to ensure that samples included in the review had not been exposed to any intervention which may have modified the association between depression, anxiety, and HRQoL over the duration of the study

included patients with a diagnosis of COPD confirmed by spirometry as an FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio <0.70 or FEV1 <80% of the predicted values according to GOLD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) criteria;Citation32 studies that included a cohort of patients with a range of chronic physical health problems including COPD were eligible only where data for COPD confirmed by spirometry were reported separately

used validated self-report measures of either general or respiratory-specific HRQoL

used validated diagnostic clinical interviews or self-report measures of depression and anxiety; clinical and subthreshold symptoms of depression and anxiety were included.

Studies where depression and anxiety were measured using a subscale of a quality of life measure were excluded. Studies were not excluded by date of publication, sample size, or follow-up period. However, studies that were unpublished, published in abstract form only, or were not published in the English language were not included in this review.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened (by AB) and full papers of potentially relevant abstracts were retrieved. Full text versions of abstracts were independently screened and final decisions about eligibility were made at a consensus meeting with all review authors. Further information was requested from authors of seven papers, of whom five responded to provide additional information on their papers.

Data extraction

An electronic form was developed in Microsoft Excel for the purpose of data extraction. Data were extracted independently by two researchers (AB, CA) who each looked at all studies. Data were extracted on study design, method and place of recruitment, sample age, sex, smoking history, method of COPD diagnosis, and severity classification (FEV1). Scores for HRQoL depression and anxiety were extracted at both baseline and follow-up. Any disagreements between researchers were resolved by discussion.

The main aim of this review was to assess the strength of the longitudinal association between anxiety, depression, and HRQoL in COPD. Where these data were not available in the published papers, authors were contacted by email or letter to request the appropriate data. Where the length of follow-up varied, data were extracted and included in the meta-analysis for the time point closest to 12 months after the baseline measures were taken.

Quality assessment

Studies were rated for their quality by two researchers (AB, CA) using criteria adapted from guidance on the assessment of observational studiesCitation33 and the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies.Citation34 Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

The quality review included assessment of selection bias, response bias, the reliability and validity of data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, and whether confounding variables were adequately controlled for. Three key criteria were deemed as essential to the quality review and each study was awarded one point for each criterion met; this was then used as a framework for narrative synthesis of the results. These key criteria were: response rate of 70% or greater at baseline; control for confounding factors in analysis; and response rate greater than 70% at follow-up.Citation34

Data analysis and synthesis

Data analysis was conducted in Stata (version 12.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and Comprehensive Meta-analysis (version 2.2.064; BioStat International, Inc., Tampa, FL, USA). Where possible, indices of association between depression or anxiety and total scores for HRQoL measures were included in the meta-analysis. However, where total scores were not available, the most appropriate subscale score was used. For the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)Citation35 the Impact subscale was used because it provides a measure of social functioning and psychological disturbance associated with respiratory disease.Citation35 We aimed to extract regression coefficients where possible. However, since regression coefficients were not available in any of the studies, correlation coefficients were extracted and transformed for meta-analysis using Fisher’s Z transformation in order to normalize the distribution of r, making the variance independent of the unknown true value of the correlation.Citation36 The Z scores were then pooled across the studies using a random effects model to account for variation between studies. The pooled effect size was then converted back to a correlation coefficient.Citation37 A pooled correlation coefficient of r=0.10 was considered small, r=0.25 as moderate, and r=0.40 as large.Citation38 Where papers did not report either a correlation coefficient or the data required to compute a correlation coefficient, we contacted the corresponding author and requested the missing data. Two authors responded and supplied the relevant data.Citation39,Citation40 Statistical heterogeneity was investigated using I2 which measures the percentage of the variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity and cannot be explained by chance.Citation41 Low heterogeneity is indicated by an I2 result of ≤25%, moderate heterogeneity by around 50%, and high heterogeneity is ≥75%.Citation41

Results

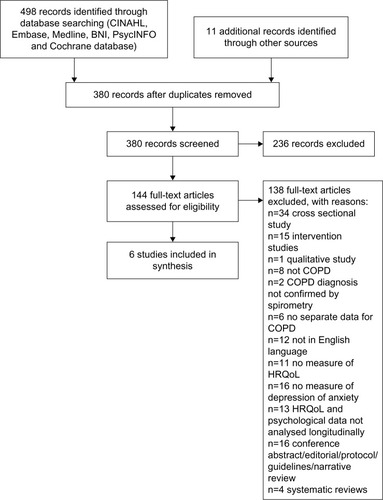

Electronic and hand searches identified 380 citations excluding duplicates. Of these, 236 citations were excluded on the basis that their abstracts did not meet the eligibility criteria for this review. The full texts for 144 citations were reviewed. Six studies were identified that met the criteria for inclusion in the systematic review,Citation39,Citation40,Citation42–Citation45 of which three were eligible for inclusion in meta-analysis for depressionCitation39,Citation40,Citation43 and two for anxiety.Citation39,Citation40 The flow of the studies and reasons for exclusion are presented in the PRISMA flow chart in .Citation31

Figure 1 Search flowchart.

Characteristics of studies and populations

The characteristics of each study are summarized in . In total, there were data for 895 COPD patients, of whom 69.8% (n=625) were male. Five of the studies included both male and female COPD patients and one was limited to male patients.Citation39 The mean age across the studies ranged from 64.6 yearsCitation44 to 73.5 years.Citation42 Length of follow-up ranged from 3 monthsCitation40 to 5 years.Citation39

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

The majority of participants (61.1%, n=547) were recruited in hospital following admission for acute exacerbations of COPD.Citation42,Citation43 The remaining 38.9% (n=348) were recruited from hospital outpatient settings. One study excluded patients who had experienced an acute exacerbation in the previous 6 weeks,Citation39 and another reported that none of the patients in their sample had been admitted for an acute exacerbation at the time they participated in the study.Citation44 All included studies recruited patients with a mean predicted FEV1 <50%, which indicates severe COPD.Citation32

Four of the six studiesCitation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation43 measured HRQoL using COPD-specific measures, including the SGRQ and the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire.Citation46 One studyCitation45 used the Sickness Impact Profile,Citation47 and another used both the Sickness Impact Profile and the SGRQ.Citation44 Four of the six studiesCitation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation44 measured symptoms of depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).Citation48 One studyCitation43 used the Hopkins Symptom Checklist,Citation49 and one study used the Profile of Mood States.Citation50 Three studies measured anxiety symptoms using the HADS.Citation39,Citation40,Citation44 No study measured panic disorder or any other specific anxiety disorders.

The prevalence of anxiety and depression varied at baseline (). The three studies that recruited patients following an admission to hospital reported that patients in their sample were experiencing symptoms of depression at baseline.Citation40,Citation42,Citation43 One study reported that 44.4% of their sample had symptoms of depression at baseline, but did not report mean HADS scores.Citation42 Three of the studies that recruited hospital outpatients reported that their sample had symptoms of depression that were not clinically significant at baseline.Citation39,Citation44,Citation45 However, one study of outpatients reported a significant increase in depressive symptoms in their sample over a 5-year study period.Citation39

Three studies measured anxiety using the HADS; two were studies of hospital outpatients and neither reported clinical levels of anxiety at baseline;Citation39,Citation44 one was a study of patients admitted to hospital and discharged to a nurse-led early discharge service and reported a mean HADS anxiety score of 8.8, indicating mild anxiety symptoms.Citation40,Citation48

Quality of included studies

The results of the quality review are presented in . The quality of the studies varied greatly. One study met the requirements for all three of the quality criteria,Citation42 two studies met two of the criteria,Citation40,Citation43 and three studies did not meet any.Citation39,Citation44,Citation45 Five out of the six studies studiesCitation39,Citation40,Citation42,Citation43,Citation45 reported attrition rates at follow-up, two of which found that those who completed the study were more likely to be younger than those who did not.Citation43,Citation45 Furthermore, in one study,Citation39 over 40% of patients who did not complete follow-up at 5 years had died. In this study, patients who had died were found to be significantly older, more breathless, and had worse HRQoL than those who did complete follow-up.

Table 2 Quality of the included studies

Longitudinal association of depression with HRQoL in COPD

Six longitudinal cohort studies investigated the association between depression and HRQoL in COPD (), but only three studies could be included in the meta-analysis for depression.Citation39,Citation40,Citation43

Ng et alCitation42 scored the highest score of 3 in the quality review and reported that depressed patients had significantly worse HRQoL at baseline across all subscales of the SGRQ, and this was maintained at 12-month follow-up. However, the authors did not analyze the predictive effect of depression on HRQoL across the 12-month period. Two of the studies scored 2 in the quality review.Citation40,Citation43 Andenaes et alCitation43 studied patients who were admitted to hospital with COPD and reported a significant correlation between depression at baseline and HRQoL on follow-up at 6 and 9 months. In this study, depression was significantly correlated with the respiratory-specific SGRQ Impact subscale (r=0.28, n=51, P<0.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] not reported) and also the physical domain (r=−0.64, n=51, P<0.01, 95% CI not reported), psychological domain (r=−0.62, n=51, P<0.01, 95% CI not reported), and environmental domain (r=−0.41, n=51, P<0.01, 95% CI not reported), but not with the social domain (r=−0.23) of the WHOQoL-BREF (World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument). Coventry et alCitation40 found that depression at baseline was significantly correlated with respiratory-specific HRQoL at 3 months (r=0.52, P<0.001) and 1-year follow-up (r=0.64, P<0.001) in patients discharged from hospital under the care of early discharge services (). Three studies did not meet any of the key quality criteria.Citation39,Citation44,Citation45 Firstly, Oga et alCitation39 reported that depression measured at baseline was significantly correlated with respiratory-specific HRQoL at 1-year follow-up (r=0.47, P<0.001); this association remained after 5 years (r=0.47, P<0.001) in the sample of outpatients with severe COPD.Citation39 Secondly, Engstrom et al found that depression as measured by the Hospital Depression and Anxiety Scale depression subscale (b=0.39, P<0.001), 6-minute walk distance (b=0.05, P<0.05), and vital capacity (b=0.15, P<0.001) were the best predictors of HRQoL, explaining 59% of the variance in multiple regression analyses when SGRQ scores were excluded.Citation44 Finally, Graydon et al found that negative mood, as measured by the Profile of Mood States at baseline, was significantly correlated with HRQoL after 12 months (r=0.49, P<0.0001, 95% CI not reported).Citation45 However, they did not include depression as a predictor variable in their multiple regression analyses.

Table 3 Longitudinal correlations between depression and HRQoL in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

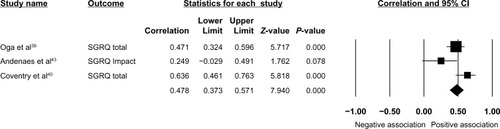

Meta-analysis of longitudinal association between depression and HRQoL in COPD

Three studies were eligible for inclusion in meta-analysis for depression.Citation39,Citation40,Citation43 Random effects meta-analysis of the three studies () found a large positive correlation between depression at baseline and HRQoL measured at follow-up (r=0.48, 95% CI 0.37–0.57, P<0.001). A moderate to high degree of heterogeneity was found across the studies (Q=6.60 df=2, P=0.037, I2=69.7%).Citation41

Figure 2 Forest plot of the longitudinal effect of depression on health-related quality of life in COPD.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

Longitudinal association of anxiety with HRQoL in COPD

Two cohort studies report the longitudinal association between anxiety and HRQoL in COPD ().Citation39,Citation40 The study by Coventry et al met two of the key quality criteria for this review and found that anxiety at baseline was significantly correlated with respiratory-specific HRQoL at 3 months (r=0.40, P=0.002) but this did not remain significant at 1-year follow-up (r=0.26, P=0.052).Citation40 The second study did not meet any of the key quality criteria but reported that anxiety was correlated with respiratory-specific HRQoL at 1-year (r=0.41, P<0.001) and 5-year follow-up (r=0.51, P<0.001).Citation39

Table 4 Longitudinal correlations between anxiety and HRQoL in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

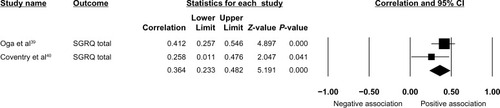

Meta-analysis of longitudinal association between anxiety and HRQoL in COPD

Two studies were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis.Citation39,Citation40 The random effects meta-analysis of the two studies () found that anxiety at baseline was associated with a moderate and significant positive correlation with HRQoL at follow-up (r=0.36, 95% CI 0.23–0.48, P<0.001). A low degree of heterogeneity was found across the studies (Q=1.22, df=1, P=0.269, I2=18.3%).

Figure 3 Forest plot of the longitudinal effect of anxiety on health-related quality of life in COPD.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; HAD-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale anxiety subscale.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies to assess the temporal association between depression and anxiety and HRQoL in COPD. We identified six studies in total, of which three met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Results indicated that both depression and anxiety predict future HRQoL. The association was stronger for depression than for anxiety.

Strengths and limitations

This review has several strengths. Firstly, the search was designed to take a broad approach to the identification of papers that included depression and anxiety. Terms to identify both clinically significant and subclinical depression and anxiety symptoms were included. Secondly, the search strategy for this review was designed to find cohort studies that had investigated the strength of the longitudinal association between depression, anxiety or panic disorder, and HRQoL in COPD which has not been done before. The decision to exclude studies where samples had been exposed to any intervention was made to ensure that any prospective change in HRQoL would be unconfounded with treatment effects. Furthermore, cohort studies are often easier to recruit into than randomized controlled trials, and therefore the samples may be less open to threats to their external validity.Citation51 The search resulted in identification of 380 studies, a relatively small number for a systematic review. Therefore, it is possible that inclusion of methodological terms to locate only prospective studies may have reduced the sensitivity of the search. However, we are confident that our search identified all potentially eligible relevant studies and we believe we have identified at least two studiesCitation40,Citation45 not included in a recent meta-analysis of studies that measured factors influencing HRQoL in COPD.Citation25 Finally, the detection of between-study variance can be interpreted as a positive finding since the very likely present heterogeneity has been identified and appropriately accounted for using a random effects model.Citation52

This review has some weaknesses. Firstly, we used a quality scoring system that presents an overall quality score which rates methodological weaknesses equally. There is a lack of empirical support for the assumption that all methodological weaknesses have equal weight. Therefore, we present details of the performance of each study on each methodological criterion and also highlight the three criteria deemed to be most important for longitudinal studies.Citation34 The quality review highlighted several methodological issues with the studies eligible for inclusion in this review. One of the studies that was rated as the highest qualityCitation42 was not eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis because data on the longitudinal association between baseline depression or anxiety and HRQoL at follow-up were not available. The three studies that did report this data were of varying quality, with two meeting two of the specified quality requirements,Citation40,Citation43 and one failing to meet any.Citation39 Only one studyCitation40 provided information on sampling and recruitment procedures and recruitment response rates.

Therefore, it was not possible to evaluate whether the sampling method was open to selection bias in the included studies of lower quality. Furthermore, none of the studies provide any comparison between those who were and those who were not recruited, making evaluation of possible response bias impossible. The inconsistent reporting of response and attrition bias throughout the studies has implications for the inferences that can be drawn from this review. It may be that the results cannot be generalized to older COPD patients because they were less likely to complete follow-up in two studies,Citation42,Citation44 although these studies were not eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. All of the included studies used validated measures of quality of life and psychological factors. However, one studyCitation43 that used the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25) modified the measure, removing two of the items relating to suicidal ideation and loss of libido, which are symptoms commonly associated with depression. This reduces the validity of the measure and may have resulted in an underestimate of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in this sample. Unpublished studies were not included in this review, which may have introduced publication bias into this review because studies that report higher effect sizes are more likely to be published.Citation53 Where total scores for HRQoL measures were not available for meta-analysis, the most appropriate subscale was chosen. In the case of one paper,Citation43 the SGRQ impact subscale was chosen because it provides a measure of social functioning and psychological disturbance that would maximize any observed association between depression and HRQoL. We did not formally test for publication bias in this review due to the small number of studies eligible for inclusion.Citation54 Finally, one of the assumptions made in random effects meta-analysis is that study effects should be normally distributed. This is not always easy to confirm when the number of studies included in the model is small. However, methods have been found to be relatively robust even under extreme distributional scenarios.Citation55

Implications for research and practice

The results of the meta-analysis show that depression and anxiety predict future HRQoL. These findings are consistent with the results of a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed the association between psychological and symptom-based factors and HRQoL in COPD patients.Citation25 Tsiligianni et al found that depression, anxiety, exercise, and dyspnea were more highly correlated with HRQoL in COPD than FEV1,Citation25 but this finding was based only on cross-sectional studies and therefore did not include several studies which were eligible to be included for meta-analysis in our review.Citation39,Citation40,Citation43 Our review, which is the first to only include longitudinal studies, has further advanced our knowledge of the association between depression and anxiety and HRQoL in COPD by showing that depression and anxiety are correlated with prospective HRQoL. Unfortunately, we were not able to compare the association between depression and anxiety and HRQoL with that of FEV1 because the necessary data were not reported in the published papers. Two authors were contactedCitation39,Citation40 and invited to provide the correlations between FEV1 and HRQoL. However, only one author responded, so the analysis could not be completed. This should be a priority for future longitudinal research in this area.

Future studies would be improved by including other common mental health problems that are prevalent in COPD. Panic disorder has a prevalence in COPD estimated to be ten times that of the prevalence in the general population.Citation56,Citation57 Panic disorder is known to have a significant negative impact on quality of life in the general populationCitation58,Citation59 and in patients with long-term conditions such as heart failureCitation60 and diabetes.Citation61 However, no studies were identified in this review that had considered the impact of panic attacks or panic disorder in COPD. Panic attacks and panic disorder comorbid with COPD have been found to cause greater levels of distress relating to physical health,Citation62 and to predict worse health outcomes, including increased hospital admissionsCitation63 and poorer functional status.Citation64 Therefore, it is important to investigate if panic disorder is a significant driver of HRQoL in COPD because it may be a more important predictor than depression or generalized anxiety.

The findings of this review highlight the importance of regularly assessing patient-centered outcomes such as HRQoL in people with COPD, regardless of their disease severity as measured by lung function. HRQoL is an important marker of functioning, and is potentially mediated by extrapulmonary features of COPD such as anxiety and depression. Whereas self-management and education have had limited impact on the psychological health of COPD patients,Citation65–Citation67 case management that draws on integrated and collaborative approaches has been shown to reduce depression and improve physical health in people with diabetes and coronary heart disease,Citation68 although their effectiveness and safety in COPD is unknown.Citation69 As well as scope for testing the acceptability and effectiveness of collaborative care models in COPD, there is also a need to test mediational models proposing that psychological processes and improvements in psychological health predict improvements in HRQoL and possibly improve physical health outcomes and responses to rehabilitation.Citation70

Conclusion

The findings of this review confirm that there is an association between depression, anxiety, and HRQoL that endures over time. However, this longitudinal analysis does not show cause and effect between depression and anxiety and future HRQoL. Future studies should identify psychological predictors of poor HRQoL in well designed prospective cohorts with a view to isolating the mediating role played by anxiety disorders and depression.

Author contributions

AB: planned and designed this systematic review and meta-analysis, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and search strategies; conducted the search, identified eligible papers, extracted the data, and performed the meta-analysis; interpreted findings and wrote the drafts of the paper for submission; coordinated with coauthors to collate comments; and wrote the final draft of the paper. CD: supervised the planning and design of this review and meta-analysis; assisted in the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria, development of search strategies, meta-analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the paper; and approved the final version of the paper. EG: supervised the planning and design of this review and meta-analysis; assisted in the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria, development of search strategies, meta-analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the paper; and approved the final version of the paper. PB: supervised the planning and design of this review and meta-analysis; assisted in the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria, development of search strategies, meta-analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the paper; and approved the final version of the paper. EK: supervised the planning and design of this review and meta-analysis; assisted in the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria, development of search strategies, meta-analysis, interpretation of findings, and drafting of the paper; and approved the final version of the paper. CA: Made a substantial contribution to the acquisition and interpretation of data by assisting in data extraction, reviewing the quality of included papers, drafting of the paper, making critical revisions to the final draft and approved the final version of the paper. PAC: supervised the planning and design of this review and meta-analysis, assisted in the development of inclusion and exclusion criteria, development of search strategies, meta-analysis, interpretation of findings, drafting of the paper; and approved the final version of the paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research under its Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (grant RP-PG-0707-10162), by the University of Manchester (PB, EK, PAC), and the National Institute for Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for the South West Peninsula (CD). This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP-PG-0707-10162). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. We wish to acknowledge the contribution of authors who provided additional information on their studies, namely, C Engstrom and T Oga.

Disclosure

None of the authors had competing interests to declare.

References

- World Health OrganizationGlobal surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory disease: a comprehensive approachGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2007 Available from: http://www.who.int/gard/publications/GARD_Manual/en/Accessed March 11, 2014

- AgustiACalverlyPCelliBEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigatorsCharacterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Res20101112220831787

- HuertasAPalangePCOPD: a multifactorial systemic diseaseTher Adv Respir Dis2011521722421429981

- JenkinsCRodriguez-RoisinRQuality of life, stage severity and COPDEur Respir J20093395395519407046

- BakasTMcMlennonSCarpenterJSystematic review of health- related quality of life outcomesHealth Qual Life Outcomes20121013423158687

- MoriartyDZackMKobauRThe Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Health Days Measures – population tracking of percieved physical and mental health over timeHealth Qual Life Outcomes200313714498988

- CurtisJPatrickDThe assessment of health status among patients with COPDEur Respir J20032136s45s

- JonesPBrusselleGDal NegroRHealth-related quality of life in patients by COPD severity within primary care in EuropeRespir Med2011105576620932736

- WeatherallMMarshSShirtcliffePWilliamsMTraversJBeaslyRQuality of life measured by the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire and spirometryEur Respir J2009331025103019164350

- MonteagudoMRodriguez-BlancoTLlagosteraMFactors associated with changes in quality of life of COPD patients: a prospective study in primary careRespir Med20131071589159723786889

- GarridoPCde Miguel DiezJGutierrezJRNegative impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on the health-related quality of life of patients. Results of the EPIDEPOC studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes200643116719899

- DonaldsonGCWilkinsonTMAHurstJRPereraWRWedzichaJAExacerbations and time spent outdoors in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200517144645115579723

- AlmagroPBarreiroBOchoa de EchaguenARisk factors for hospital readmissions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration20067331131716155352

- GudmundssonGGislasonTJansonCRisk factors for rehospitalistion in COPD: role of health status, anxiety and depressionEur Respir J20052641441916135721

- OsmanIGoddenDFriendJLeggeJDouglasJQuality of life and hospital re-admission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax19975267719039248

- AlmagroPCalboEOchoa de EchaguenAMortality after admission for COPDChest20021211441144812006426

- Domingo-SalvanyALamarcaRFerrerMHealth-related quality of life and mortality in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200216668068512204865

- CrockettACranstonJMossJAlpersJThe impact of anxiety, depression and living alone in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseQual Life Res20021130931612086116

- Al-shairKDockryRMallia-MilanesBKolsomUSinghDVetsboJDepression and its relationship with poor exercise capacity, BODE index and muscle wasting in COPDRespir Med20091031572157919560330

- Martinez FrancesMTorderaMFusterAMartinez MoragonETorreroLImpact of baseline and induced dyspnea on the quality of life of patients with COPDArch Bronconeumol200844127134 Spanish18361883

- QuintJBaghai-RavaryRDonaldsonGWedzichaJRelationship between depression and exacerbations in COPDEur Respir Rev2008325360

- Di MarcoFVergaMReggenteMAnxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severityRespir Med20061001767177416531031

- PeruzzaSSergiGVianelloAChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in elderly subjects: impact on functional status and quality of lifeRespir Med20039761261712814144

- BalcellsEGeaJFerrerJFactors affecting the relationship between psychological status and quality of life in COPD patientsHealth Qual Life Outcomes2010810820875100

- TsiligianniIKocksJTzanakisNSiafakasNvan der MolenTFactors that influence disease-specific quality of life or health status in patients with COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis or Pearson correlationsPrim Care Respir J20112025726821472192

- IguchiASenjyuHHayashiYRealtionship between depression in patients with COPD and the percent of predicted FEV1, BODE index, and health-related quality of lifeRespir Care20135833433922782453

- BorosPLubinskiWHealth state and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Poland: a study using the EuroQoL-5D questionnairePol Arch Med Wewn2012122738122354456

- StewartAHaysRWareJThe MOS Short Form General Health SurveyMed Care1988267247353393032

- KimHKunikMMolinariVFunctional impairment in COPD patients: the impact of anxiety and depressionPsychosomatics20004146547111110109

- FelkerBKatonWHedrickSThe association between depressive symptoms and health status in patients with chronic pulmonary diseaseGen Hosp Psychiatry200123566111313071

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statementBMJ2009339b253519622551

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease2010 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLDReport_April112011.pdfAccessed March 11, 2014

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination University of YorkSystematic ReviewsCRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care2009 Available from: http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdfAccessed March 11, 2014

- ThomosBCiliskaDDobbinsMMicucciSA process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventionsWorldviews Evid Based Nurs2004117618417163895

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMThe St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireRespir Med19918525311759018

- HedgesLOlkinIStatistical Methods for Meta-AnalysisOrlando, FL, USAAcademic Press1985

- BorensteinMHedgesLHigginsJRothsteinHIntroduction to Meta-Analysis1st edNew York, NY, USAWiley2009

- LipseyMWilsonDPractical Meta-AnalysisLondon, UKSage Publications2001

- OgaTNishimuraKTsukinoMSatoSHajiroTMishimaMLongitudinal deteriorations in patient reported outcomes in patients with COPDRespir Med200710114615316713225

- CoventryPGemmellIToddCPsychosocial risk factors for hospital readmission in COPD patients on early discharge services: a cohort studyBMC Pulm Med2011114922054636

- HigginsJThompsonSDeeksJAltmanDMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysisBMJ200332755756012958120

- NgTNitiMTanWCaoZOngKEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med2007167606717210879

- AndenaesRMoumTKalfossMWahlAChanges in health status, psychological distress, and quality of life in COPD patients after hospitalisationQual Life Res20061524925716468080

- EngstromCPerssonLLarssonSSullivanMHealth related quality of life in COPD: why both disease-specific and generic measures should be usedEur Respir J200118697611510808

- GraydonJRossEWebsterPGoldsteinRAvendanoMPredictors of functioning of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHeart Lung1995243693758567301

- GuyattGHBermanLBTownsendMPugsletSOChamberLWA measure of quality of life for clinical trials in chronic lung diseaseThorax1987427737783321537

- GilsonBGilsonJBergnerMThe sickness impact profile. Development of an outcome measure of health careAm J Public Health197565130413101200192

- ZigmondASnaithRThe Hospital Anxiety and Depression ScaleActa Psychiatr Scand1983673613706880820

- DerogatisLRLipmanRSRickelsKUhlenhuthEHCoviLThe Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventoryBehav Sci1974191154808738

- McNairDMLorrMDropplemanLFProfile of Mood StatesSan Diego, CA, USAEducational and Industrial Testing Service1981

- PatelMDokuVTennakoonLChallenges in recruitment of research participantsAdv Psychiatr Treat20039229238

- KontopantelisESpringateDReevesDA re-analysis of the Cochrane Library data: the dangers of unobserved heterogeneity in meta-analysisPLoS One201387e6993023922860

- DickersinKPublication bias: recognizing the problem, understanding its origins and scope, and preventing harmRothsteinHSuttonABorensteinMPublication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and AdjustmentsNew York, NY, USAWiley2005

- EggerMDavey-SmithGSchneiderMMinderCBias in meta- anlaysis detected by a simple, graphical testBMJ19973156296349310563

- KontopantelisEReevesDPerformance of statistical methods for meta-analysis when true study effects are non-normally distributed: a simulation studyStat Methods Med Res20122140942621148194

- LivermoreNSharpeLMcKenzieDPrevention of panic attacks and panic disorder in COPDEur Respir J20103555756319741029

- WillgossTYohannesAAnxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewRespir Care20135885886622906542

- DavidoffJChistensenSKhaliliDNguyenJIshakWQuality of life in panic disorder: looking beyond symptom remissionQual Life Res20122194595921935739

- SherbourneCWellsKJuddLFunctioning and well-being of patients with panic disorderAm J Psychiatry19961532132188561201

- Muller-TaschTFrankensteinLHolzapfelNPanic disorder in patients with chronic heart failureJ Psychosom Res20086429930318291245

- LudmanEKatonWRussonJPanic episodes among patients with diabetesGen Hosp Psychiatry20062847548117088162

- DowsonCKuijerRTownIMulderRImpact of panic disorder upon self-management educational goals in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChron Respir Dis20107839020299537

- YellowleesPAlpersJBowdenJBryantGRuffinRPsychiatric morbidity in patients with chronic airflow obstructionMed J Aust19871463053073821636

- MooreCZebbBFunctional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the moderating effects of panicInt J Rehabil Health199848393

- EffingTMonninkhofEvan der ValkPZeilhuisGvn der PalenJZwerinkMSelf-management education in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Cochrane Database Syst Rev20074CD00299017943778

- McGeochGWillsmanKDowsonCSelf-management plans in the primary care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology20061161161816916335

- CoventryPBowerPKeyworthCThe effect of complex interventions on depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS One20138e6053223585837

- KatonWLinEVon KorffMCollaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnessN Engl J Med20103632611262021190455

- FanVGazianoMLewRA comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized controlled trialAnn Intern Med201215667368322586006

- BoersmaSMaesSJoekesKDusseldorpEGoal processes in relation to goal attainment: prediciting health-related quality of life in myocardial infarction patientsJ Health Psychol20061192794117035264