Abstract

Dyspnea, exercise intolerance, and activity restriction are already apparent in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, patients may not seek medical help until their symptoms become troublesome and persistent and significant respiratory impairment is already present; as a consequence, further sustained physical inactivity may contribute to disease progression. Ventilatory and gas exchange impairment, cardiac dysfunction, and skeletal muscle dysfunction are present to a variable degree in patients with mild COPD, and collectively may contribute to exercise intolerance. As such, there is increasing interest in evaluating exercise tolerance and physical activity in symptomatic patients with COPD who have mild airway obstruction, as defined by spirometry. Simple questionnaires, eg, the modified British Medical Research Council dyspnea scale and the COPD Assessment Test, or exercise tests, eg, the 6-minute or incremental and endurance exercise tests can be used to assess exercise performance and functional status. Pedometers and accelerometers are used to evaluate physical activity, and endurance tests (cycle or treadmill) using constant work rate protocols are used to assess the effects of interventions such as pulmonary rehabilitation. In addition, alternative outcome measurements, such as tests of small airway dysfunction and laboratory-based exercise tests, are used to measure the extent of physiological impairment in individuals with persistent dyspnea. This review describes the mechanisms of exercise limitation in patients with mild COPD and the interventions that can potentially improve exercise tolerance. Also discussed are the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation and the potential role of pharmacologic treatment in symptomatic patients with mild COPD.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable, and treatable disease, characterized by chronic inflammation of the airways and lungs, persistent airflow limitation, and, in many, a progressive decline in lung function. It is associated with significant morbidity and increased mortality,Citation1,Citation2 even in patients with mild airflow obstruction. Despite this prospect, the disease often goes undiagnosed and untreated until it has progressed to a point where lung function and quality of life are severely compromised.Citation3,Citation4

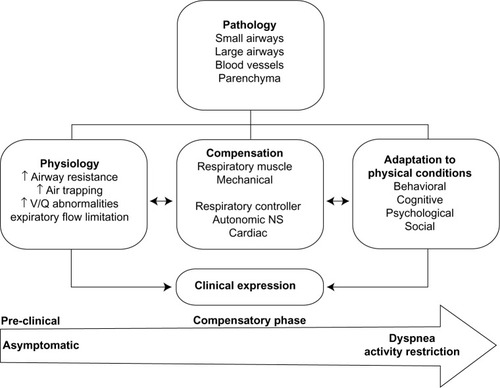

The clinical expression of COPD in its early phase of development depends on the integration of several factors, which include: the nature and extent of the physiological impairment; the compensatory responses mobilized to maintain effective pulmonary gas exchange; and the subjective behavioral response to encroachment of the respiratory reserve (eg, activity avoidance) (). In the current review, the main focus is on smokers with apparently mild airway obstruction but who report persistent activity-related dyspnea.

Figure 1 Characterization of mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Physical inactivity is often the consequence of troublesome dyspnea and is considered to be a major contributor to the progression of COPD, which, in turn, has been associated with the development of comorbidities, increased risk for hospitalization and associated health care costs, and increased rates of mortality.Citation5,Citation6 Physical inactivity is also considered by some to cause systemic inflammation, which leads to development of comorbidities, such as COPD.Citation7,Citation8 By contrast, regular physical activity is known to reduce rates of hospitalization and all-cause and respiratory mortality in patients with COPD,Citation6,Citation9 although the impact of physical activity in mild disease is less well understood.

In the past, there has been a perception that mild airway obstruction, as defined by spirometry (ie, post-bronchodilator forced expiratory flow in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity <0.7 and FEV1 >80 % predicted), has few clinical consequences and does not require intervention.Citation10 However, there is mounting evidence that mild airflow obstruction is associated with a reduction in exercise capacity in patients with COPD.Citation5,Citation11,Citation12 Even before patients are aware of their illness, they often habitually restrict some of their more strenuous activities to avoid unpleasant symptoms, such as dyspnea. Over time, this can lead to a spiral of worsening symptoms, deconditioning, and exercise intolerance as patients become progressively more sedentary,Citation13 and provides a compelling rationale for consideration of early intervention.

Smoking cessation is the pivotal and most effective intervention in patients with COPD.Citation14,Citation15 It is also well established that pharmacologic treatment, together with nonpharmacologic interventions, can effectively reduce the intensity of dyspnea and improve exercise capacity in moderate-to-severe COPD,Citation1,Citation16,Citation17 although this is not well documented in mild disease.

This review summarizes the importance and benefits of encouraging physical activity and exercise in mild COPD, with a focus on alternative outcome measurements, such as small airway dysfunction and exercise abnormalities, which are already apparent in the mild stage of the disease.Citation10,Citation11,Citation18,Citation19 Also discussed are the potential benefits for patients with mild COPD of smoking cessation, regular physical activity, and pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), in combination with pharmacologic treatment, which have already been shown to improve dyspnea, quality of life, exercise endurance, and functional capacity of patients with more advanced disease.Citation20

Exercise abnormalities in COPD

Exercise and activity limitation are already apparent in patients at the mild stage of COPD (Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] 1),Citation1,Citation10,Citation11,Citation18 with exercise tolerance becoming increasingly compromised with disease progression.Citation5,Citation21 Exertional dyspnea and leg discomfort are common exercise-limiting symptoms in patients with COPD, including symptomatic patients with mild airflow obstruction.Citation11,Citation18 Both symptoms result from a complex interaction of factors, such as baseline respiratory mechanical dysfunction,Citation22 individual susceptibility to leg muscle fatigue,Citation23 type of exercise,Citation24–Citation26 and bronchodilation status,Citation27–Citation29 the consequences of which vary from patient to patient. As dyspnea and leg fatigue worsen, the patient leads a more sedentary lifestyle in order to avoid these symptoms, resulting in skeletal muscle deconditioning, exercise intolerance, and poor quality of life.Citation13

Mechanisms of exercise limitation in mild symptomatic COPD

Patients with mild COPD exhibit a diverse range of structural abnormalities of the lungs and airways, including airway wall thickening, pulmonary gas trapping, emphysema, and vascular dysfunction.Citation30–Citation32 As a result, these patients display substantial heterogeneity in airways resistance and conductance, pulmonary gas trapping, resting (static) lung hyperinflation, and integrity of the alveolar–capillary gas exchange interface.Citation33 Recent evidence has also shown that dynamic hyperinflation (during exercise) occurs in many patients with mild COPD, independently of whether patients have resting hyperinflation.Citation34 Understanding the structure–function relationships in the lungs and airways may assist understanding of exercise limitations in COPD.

Small airway dysfunction

The small airways, ie, those <2 mm in diameter, are the major sites of obstruction in patients with COPD.Citation35 Narrowing, occlusion, and loss of small airways have been confirmed from resected lung specimens, even in patients with mild COPD, using quantitative computed tomography,Citation19,Citation35,Citation36 and are associated with enhanced inflammatory and repair responses, as well as a build-up of inflammatory mucus exudates in some patients.Citation36 Recent findings suggest that these changes precede the onset of centrilobular emphysema.Citation19

Persistent expiratory flow limitation (EFL) is the defining feature of COPD. It occurs when expiratory flow cannot be increased because it is already at maximum during spontaneous tidal breathing at that lung volume. EFL arises due to the combined effects of airway narrowing, diminished lung elastic recoil, airway–parenchyma uncoupling, and dynamic airway collapse.Citation37–Citation39 The relative contribution of each of these factors to EFL in patients with mild COPD varies from patient to patient and is difficult to quantify conclusively.Citation38,Citation40

Ventilation/perfusion (VA/Q) abnormalities

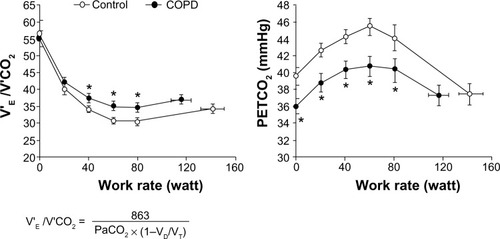

Patients with mild-to-moderate COPD commonly exhibit abnormal VA/Q mismatch while breathing at rest, despite a largely preserved FEV1.Citation41–Citation43 Resting alveolar-to-arterial oxygen tension gradient has been shown to be abnormally widened (>15 mmHg) in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD who have regional low VA/Q ratios.Citation41,Citation42 In patients with emphysematous destruction, high VA/Q ratios (and wasted ventilation) may be dominant. Such patients exhibit a decreased surface area for gas exchange, as evidenced by a reduced diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, and small vessel disease, both of which have been demonstrated in patients with mild COPD.Citation30,Citation41–Citation44 These abnormalities likely contribute to a higher ventilatory requirement during exercise in patients with mild COPD ().

Figure 2 Ventilatory insufficiency in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. V’E/V’CO2 (left) and PETCO2 (right) in response to symptom-limited incremental cycle exercise in patients with mild COPD and healthy controls (Mean ± SE) at rest, 20, 40, 60, and 80 watt during exercise and at peak exercise (*P<0.05) COPD versus control at a standardized work rate (watt).

Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2013 American Thoracic Society. Ofir D, Laveneziana P, Webb KA, Lam YM, O’Donnell DE. Mechanisms of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(6):622–629. Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society.Citation11

Responses to exercise in mild COPD

High ventilatory demand

Peak oxygen consumption (V’O2) and minute ventilation (V’E) are reduced, and perceived dyspnea is increased during incremental exercise to tolerance in patients with mild COPD compared with healthy controls.Citation10,Citation11,Citation18,Citation45,Citation46 By contrast, ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide (V’E/V’CO2) output is consistently higher during cycleCitation10,Citation11,Citation18 and treadmill exercise testCitation46 in this patient population. This abnormality may reflect an impaired ability to reduce higher physiologic dead space during exercise in patients with mild COPD, an altered set-point for arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, or a combination of the two. However, significant arterial O2 desaturation (>5%) has not been reported during incremental cycle exercise,Citation10,Citation11,Citation18,Citation45 suggesting that compensatory increases in V’E, and normal increase in cardiac output, ensure an improved VA/Q relationship during exercise in these patients.Citation41,Citation42,Citation47 In some patients, earlier metabolic acidosis, as a result of skeletal muscle deconditioning, provides an added stimulus to V’E during exercise.Citation11,Citation18

Impairment of dynamic respiratory mechanics

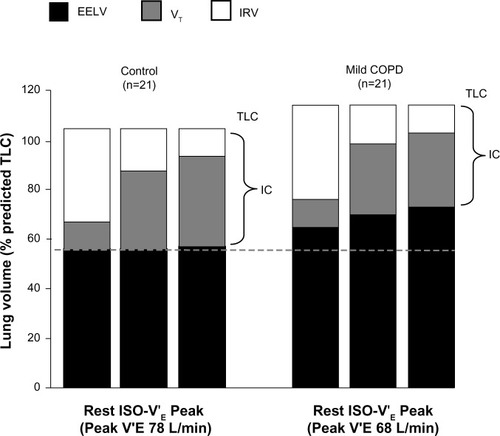

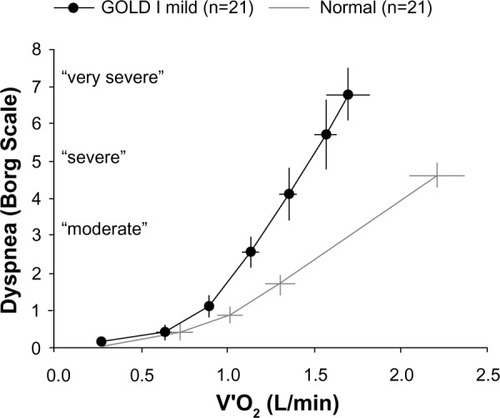

In addition to higher ventilatory requirements, dynamic gas trapping and mechanical constraints on tidal volume (VT) expansion may contribute to reduced peak V’O2 and V’E in patients with mild COPD.Citation10,Citation11,Citation18,Citation45 Exercise-induced gas trapping occurs through a combination of tachypnea and EFL: end-expiratory lung volume (EELV) increases and inspiratory capacity decreases (), which is reflected in the dyspnea slope that was significantly (P<0.05) steeper in patients with GOLD 1 COPD compared with normal healthy controls ().Citation11 Thus, expiratory time becomes insufficient to allow EELV to decline to its natural relaxation volume between breaths and becomes dynamically (rather than statically) determined.

Figure 3 Operating lung volumes during exercise.

Note: Data from Ofir D, Laveneziana P, Webb KA, Lam YM, O’Donnell DE. Mechanisms of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(6):622–629. Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society.Citation11

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; EELV, end-expiratory lung volume; IC, inspiratory capacity; IRV, inspiratory reserve volume; ISO-V’E, isotime minute ventilation; TLC, total lung capacity; VT, tidal volume.

Figure 4 Exertional dyspnea intensity

Abbreviations: GOLD, Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; V’O2, oxygen consumption.

Previous studies in healthy individuals have shown that selective stressing of the respiratory system, by adding dead space to the breathing apparatus, results in significant increases in peak VT and V’E and a preservation of exercise capacityCitation49–Citation51. By contrast, the ability of patients with advanced COPD to increase V’E in response to such added chemostimulation is markedly diminished,Citation52 and suggests that impaired respiratory mechanics represent the proximate limitation to exercise in COPD. These findings were recently extended to patients with mild COPD.Citation18 In this latter group, an inability to further increase end-inspiratory lung volume, VT, and V’E at the peak of exercise in response to dead space loading indicated that the respiratory system had reached its physiological limits at the end of exercise. Moreover, this abnormality occurred in a setting of adequate cardiac reserve. Such critical mechanical constraints on VT expansion during added dead space breathing were associated with an earlier onset of intolerable dyspnea in patients with mild COPD but not in healthy controls.Citation18

Mechanical studies have also confirmed that dynamic lung compliance is decreased and pulmonary resistance, rest-to-peak changes in EELV, intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressures, and oxygen cost and work of breathing are increased in symptomatic patients with mild COPD compared with healthy controls.Citation11,Citation45

Cardiocirculatory impairment

As smoking history is a common risk factor for both COPD and cardiovascular disease, it is not surprising that patients with COPD display a range of cardiocirculatory abnormalities. Historically, it was widely believed that cardiovascular complications occurred only in patients with advanced disease as a consequence of chronic hypoxemia, eg, pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale. More recently, however, it is recognized that cardiovascular dysfunction is a common comorbidity in mild-to-moderate COPD.Citation53–Citation59

In a large Danish population study, the presence of dyspnea and mild airway obstruction was shown to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality.Citation60 Preclinical, mild airflow obstruction is associated with smaller left ventricular end-diastolic volumes and decrements in stroke volume and cardiac output.Citation53,Citation54 Minor, increased emphysema is also associated with impaired left ventricular diastolic function and reduced cardiac output.Citation54,Citation55 Emphysematous destruction of lung parenchyma and pulmonary capillary beds, endothelial dysfunction, reduced pulmonary blood flow, and increased pulmonary vascular resistance have been suggested as possible underlying mechanisms responsible for these abnormalities.Citation53,Citation54

Skeletal muscle dysfunction

Activity limitation inevitably leads to deconditioning and skeletal muscle dysfunction, manifested as marked declines in muscle mass and strength, which contribute to impaired mobility, poor health status, and further exercise intolerance.Citation1,Citation61 There is a growing appreciation that structural and functional abnormalities of the skeletal muscles can develop in patients with mild COPD.Citation62–Citation65 Skeletal muscle impairment may, in turn, lead to reduced exercise capacity.Citation12 Muscle injury,Citation62 loss of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity, and diminished enduranceCitation63 have been reported in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD and appear to develop in the absence of significant muscle wasting.Citation12

Physical inactivity and deconditioning are thought to contribute to skeletal muscle dysfunction, and the initiation of exercise training programs has been shown to improve muscle function;Citation66 however, physical inactivity is not thought to be the sole determinant of muscle impairment in mild-to-moderate COPD.Citation63 Muscle impairment worsens with progressive lung function, suggesting the involvement of oxidative stress.Citation63 Active smoking may also play a significant role due to its negative impact on muscle bioenergetics and protein synthesis.Citation63

Assessment of exercise tolerance

Due to the detrimental role of physical inactivity in COPD, a complete patient assessment should include both assessment of usual activity levels and measurement of lung function. Clinical trials of interventions for COPD frequently assess physical activity using either subjective methods, including patient diaries and questionnaires,Citation67 or objective methods, eg, pedometersCitation68 or accelerometers.Citation67 Subjective methods are inexpensive, easy to administer, and represent the patients’ perspective on their functional status. A wide variety of simple questionnaires for quantifying physical activity has been reviewed.Citation67 These methods do have their limitations, such as the potential for erroneous reporting, recall bias, and interpretation issues.Citation69

Simple assessment of physical activity and symptoms may help reveal the impact of COPD on patients’ daily lives. Pedometers count the number of steps taken by detecting vertical movements, but can underestimate slow walking, such as in elderly patients,Citation70 and provide no information about the time spent in individual activities or the intensity of the activities performed.Citation67 Accelerometers are more technologically advanced than pedometers, and multiaxial devices are able to detect movement in multiple planes of motion.Citation71 Unlike pedometers, accelerometers are also generally capable of recording and storing information on exercise intensity. Newer devices, incorporating multiaxial accelerometers and multiple physiological sensors, are able to estimate energy expenditure even at the slow walking pace typical of elderly patients with COPD.Citation72,Citation73 The significance of assessing physical activity was demonstrated in a recent study, which found that all-cause mortality in patients with COPD was best predicted using objective measures of physical activity.Citation74

Endurance tests using constant work rate (CWR) protocols, ie, cycle ergometer or treadmill, are often used to assess the effects of PR because exercise training has little effect on maximal exercise capacity but can improve endurance.Citation75 Furthermore, CWR protocols are gaining popularity because they are able to assess improvements in endurance as a result of PRCitation75 and are responsive to the beneficial effects of bronchodilators on symptoms that limit exercise tolerance.Citation45,Citation76–Citation79

Simple assessment of physical activity

Simple assessment of physical activity in patients with COPD is by the use of tools or questionnaires designed to assess a patient’s ability to accomplish basic and instrumental activities of daily living,Citation80 eg, the well-established London Chest Activity of Daily Living scale (LCADL), which assesses dyspnea during a patient’s activities.Citation81 Interestingly, a recent systematic review has concluded that assessment of activities of daily living should be used more often as a clinical outcome in the management of patients with COPD.Citation82

The modified British Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scaleCitation83 and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT© 2009; GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, UK)Citation84 are used by the GOLD guidelines for symptom/risk evaluation.Citation1 Together, these questionnaires represent valuable tools for pulmonologists that can help to provide a clear assessment of an individual’s disease severity. The mMRC dyspnea scale uses a simple grading system to assess a patient’s level of dyspnea from 0 (only breathless with strenuous exercise) to 4 (too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing).Citation83 The majority of patients with mild (FEV1 >80% predicted) airflow obstruction provide a score of 0–1 on the mMRC dyspnea scale.Citation12,Citation85 The mMRC dyspnea scale is also used to help calculate the dyspnea arm of the BODE Index: body mass index (B), airflow obstruction (O), dyspnea (D), and exercise tolerance (E),Citation86 which is used to predict mortality in COPD. Validation of the BODE Index has shown that a BODE score of 3–4 and mild-to-moderate airflow limitation (FEV1 >50%) are associated with a similar survival probability (~0.7).Citation87

The CAT is a questionnaire used to measure the overall impact of COPD on a patient’s life. It consists of eight items, each scored 0 (no impact) to 5 (very severe impact), giving a total score range of 0–40, where a higher CAT score indicates that COPD is having a more severe impact on a patient’s life. In a recent European cross-sectional study, Jones et alCitation85 proposed that a CAT score ≥10 is clinically meaningful, and showed that patients with mild airflow obstruction already display significant health status impairment (CAT score ~16). While the total CAT score does not provide a specific evaluation of dyspnea and activity limitation, it can help to identify patients in whom these two symptoms are perceived as problematic.

6-minute walking distance test (6MWT)

The 6MWT is a practical method of assessing exercise tolerance and tracking functional changes in patients with COPD. Requiring little more than a 100-foot hallway and a stopwatch, the 6MWT measures the distance that a patient can walk on a flat, hard surface over 6 minutes. In contrast to tests that focus on a single component of physical function, the 6MWT evaluates the integrated response of pulmonary, cardiovascular, and muscular components.

Because the 6MWT is self-paced and dependent on patient motivation, the test measures submaximal exercise tolerance rather than exercise capacity.Citation88 However, because most activities are performed at submaximal levels, the 6MWT is believed to provide useful information regarding activities of daily living, in that patients with a severely impaired 6-minute walking distance are likely to have very low physical activity levels in daily life.Citation21 It is also better tolerated than other walking tests.Citation89

Results of the 6MWT have been correlated with health status, dyspnea at rest, maximum exercise capacity, and mortality.Citation90–Citation92 The 6MWT distance speed is generally similar between patients with mild COPD and healthy controls.Citation93 However, Díaz et alCitation12 recently showed that the 6MWT distance is significantly reduced in dyspneic patients with mild COPD, compared with non-dyspneic patients and smoker controls.

Incremental (ISWT) and endurance (ESWT) shuttle walking tests

Similar to the 6MWT, the ISWT is a field-based walking test, which does not require expensive equipment. However, unlike the 6MWT, the ISWT is externally paced and walking speed is incrementally increased each minute until the patient is limited by symptoms. The ISWT was developed to provide a field-based equivalent of the more advanced laboratory-based tests that measure peak exercise capacity.Citation94,Citation95 A variation of the ISWT, the ESWT is conducted at a constant pace (80%–85% of peak effort based on a prior ISWT) and continues until the patient is limited by symptoms.Citation96 A number of studies have demonstrated that the ESWT is responsive to the effects of bronchodilators on exercise toleranceCitation26,Citation97,Citation98 and may have better discriminative properties than the 6MWT.Citation97

There is a paucity of studies that have evaluated ISWT and ESWT in patients with mild COPD. In one small study, Boer et alCitation99 suggest that there is no significant difference in ISWT distance between patients with mild COPD and smoker controls, despite a significant difference between patients with moderate COPD and smoker controls.

Laboratory cardiopulmonary exercise testing

Although laboratory tests of exercise performance are not widely available, they can be very useful in evaluating the nature and extent of physiological impairment on an individual basis and can help in the planning of personalized treatment. Incremental cycle and treadmill tests represent the gold standard for the evaluation of integrated physiological responses to the stress of physical activity. These tests are particularly valuable for the investigation of disproportionate dyspnea and/or unexplained exercise intolerance in patients with mild airway obstruction. Consistent abnormalities in mild COPD include: increased dyspnea and leg discomfort ratings (as measured using the Borg ScaleCitation48); decreased peak oxygen uptake and work rate; increased ventilatory inefficiency; increased gas trapping (as measured by serial inspiratory capacity measurements); and a relatively rapid shallow breathing pattern with an early plateau of VT.Citation10,Citation11,Citation18,Citation45,Citation100 In some patients, cardiac abnormalities or increased arterial oxygen desaturation are uncovered.

Therapy of COPD

At present, smoking cessation is the only intervention that has been conclusively shown to slow the progression of COPDCitation14,Citation15 and should be implemented in all patients as early as possible,Citation1 but a recent systematic review of studies in mild-to-moderate COPD (patients with FEV1 ≥50 % predicted) has shown that, in addition to smoking cessation, pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment initiated in the early stages of the disease can also have a beneficial effect on disease symptoms and prognosis.Citation101 Nonetheless, relieving symptoms and improving exercise tolerance are increasingly recognized as important goals of treatment for COPD, and benefits can be achieved using both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.Citation1,Citation16,Citation17

Pharmacologic therapy

Maintenance therapy of COPD with long-acting bronchodilators can significantly reduce the impact of the disease.Citation102–Citation104 In patients with COPD and persistent activity-related dyspnea, it is important to first achieve sustained bronchodilation and lung deflation to reduce dyspnea, allowing patients to engage more in activities of daily living.

The GOLD guidelinesCitation1 assign patients with COPD to four separate groups (A–D) on the basis of combined assessment of airflow limitation, symptoms, and exacerbation risk, and provide recommendations for initial pharmacologic treatment based on these groups (). To date, there is insufficient evidence for recommendations for the pharmacologic treatment of patients with few symptoms and at low risk (group A).

Table 1 Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease recommendations for initial pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

For patients with spirometrically confirmed COPD who report persistent activity-related dyspnea, the initial goal is to reduce EFL in order to address lung hyperinflation and dyspnea. By virtue of their ability to relax airway smooth muscle tone, all classes of bronchodilators enhance lung emptying and increase inspiratory capacity.Citation27,Citation105–Citation107 The majority of clinical studies of bronchodilators for COPD have been conducted in patients with more severe airflow limitation (GOLD 3 and GOLD 4, groups C and D), and their efficacy in improving lung function, symptoms, and exercise tolerance is well established in these patients.Citation27–Citation29,Citation76–Citation78,Citation106 However, there is an increasing body of evidence on the pharmacological treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate COPD that supports treatment at the early stages of the disease.Citation108,Citation109

The effects of short-acting bronchodilators on exercise tolerance have been examined in symptomatic patients with mild airflow limitation (equivalent to group B).Citation45,Citation110 Despite modest improvements in airway function, operating lung volumes, and dyspnea intensity, short-acting agents yield no significant improvements in exercise endurance. Correspondingly, the GOLD guidelinesCitation1 view long-acting bronchodilators as superior to short-acting bronchodilators for patients in group B; however, this recommendation is based on expert consensus opinion rather than evidence from clinical trials.

The results from a study by Casaburi et al; unpublished data, 2014 ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT1072396) indicated that tiotropium significantly improved exercise duration compared with placebo in patients with GOLD 2 COPD (although not in patients with GOLD 1 COPD), and this improvement was associated with significant improvements in dynamic lung hyperinflation. This study has the largest cohort to date on which the effects of bronchodilator treatment in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD (48 patients with GOLD 1 COPD and 78 patients with GOLD 2 COPD) have been assessed. Further investigations are clearly warranted into the benefits of bronchodilator treatment in mild COPD and the long-term effects of bronchodilators on physical activity.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Every effort should be made to inform patients with COPD about the benefits of physical activity due to its correlation with all-cause mortality. Exercise training improves skeletal muscle function to reduce ventilatory requirements, leading to reductions in dynamic hyperinflation and exertional dyspnea.Citation20 Thus, exercise training may interrupt the cycle of decline leading to inactivity. Exercise training serves as the cornerstone of PR, which also includes patient assessment, self-management education, nutritional intervention, and psychosocial support.Citation111 Multiple guidelines for COPD recommend PR for all symptomatic patients, regardless of disease severity.Citation1,Citation17,Citation20 These recommendations are based on evidence for improvement in dyspnea, quality of life, exercise endurance, and functional capacity, for which PR is stronger than almost any other therapy in COPD;Citation20 PR has also been shown to have a beneficial effect in reducing levels of anxiety and depression, which are common comorbidities also seen in mild-to-moderate COPD.Citation1,Citation112,Citation113

Despite these recommendations, there have been few studies to evaluate the benefits of PR in patients with mild COPD. The findings of an early systematic review suggested that physical activity can significantly improve physical fitness in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD.Citation114 However, no improvements to health-related quality of life or dyspnea were reported. A more recent systematic review indicated there were significant, positive effects of PR on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with mild COPD.Citation115 Nevertheless, the impact of PR on health care resource use and lung function in patients was inconclusive. Together, these findings suggest that patients with mild COPD may benefit from PR programs as a part of their disease management, but further prospective studies are required.

Conclusion

Accumulating evidence suggests that pathological changes leading to exercise limitation are present even in symptomatic patients with mild COPD, and such patients show evidence of impairment in the form of increased exertional dyspnea and leg discomfort.Citation1,Citation10,Citation11,Citation18 Although the mechanisms of this impairment are multifactorial, abnormal ventilatory mechanics linked to EFL, lung hyperinflation, ventilatory inefficiency, and exertional dyspnea are central to the process.Citation5,Citation10–Citation12,Citation18,Citation19 Patients adapt to exertional dyspnea by decreasing physical activity, beginning with nonessential leisure activities, and progressing to include basic activities of daily living. This reduction in physical activity leads to deconditioning, which not only worsens dyspnea, but also negatively affects health status and prognosis.Citation13

Pulmonologists have a range of tools, including the 6MWT, ISWT, ESWT, laboratory-based tests including the CWR test, and physical activity assessments (eg, questionnairesCitation80,Citation83,Citation86,Citation116 and pedometers and accelerometersCitation67,Citation68,Citation71–Citation73) by which to measure levels of physical activity in symptomatic mild COPD patients. In addition, a range of pharmacologicCitation27,Citation76–Citation78,Citation106 and nonpharmacologic (smoking cessation, exercise training, and PR) treatments are available to manage COPD,Citation1,Citation16,Citation17 although their potential benefits in mild disease are inconclusive. This review highlights recent evidence that exercise intolerance and activity limitation are apparent even in mild disease,Citation10,Citation11,Citation18 with the reasonable hope that early intervention can help reduce disease progression in these patients, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality and, consequently, the need for hospitalizations and associated health care costs. Additional prospective clinical trials are urgently needed to determine if earlier introduction of pharmacotherapy is effective in patients with mild COPD.

Acknowledgments

The authors meet the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and were involved at all stages of manuscript development. This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI) and Pfizer Inc. Writing, editorial support, and formatting assistance was provided by Gill Sperrin CBiol MSB CMPP and Neil M Thomas PhD, of Envision, which was contracted and compensated by BIPI and Pfizer Inc. for these services.

Disclosure

Dr O’Donnell has received grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline, and personal fees from AstraZeneca. Dr Gebke has received personal fees from Pfizer and Boehringer Ingelheim. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPDGlobal initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) updated 2014. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/Accessed January 27, 2014

- Morbidity and Mortality: 2009 Chart Book on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood DiseasesBethesda, MDNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute2009 Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/2009_ChartBook.pdfAccessed January 27, 2014

- MapelDWDalalAABlanchetteCMPetersenHFergusonGTSeverity of COPD at initial spirometry-confirmed diagnosis: data from medical charts and administrative claimsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011657358122135490

- BednarekMMaciejewskiJWozniakMKucaPZielinskiJPrevalence, severity and underdiagnosis of COPD in the primary care settingThorax20086340240718234906

- TroostersTSciurbaFBattagliaSPhysical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-studyRespir Med20101041005101120167463

- Garcia-AymerichJLangePBenetMSchnohrPAntóJMRegular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort studyThorax20066177277816738033

- ten HackenNHPhysical inactivity and obesity: relation to asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?Proc Am Thorac Soc2009666366720008872

- BruunsgaardHPhysical activity and modulation of systemic low-level inflammationJ Leukoc Biol20057881983516033812

- Garcia-AymerichJFarreroEFélezMAIzquierdoJMarradesRMAntóJMEstudi del Factors de Risc d’Agudització de la MPOC investigatorsRisk factors of readmission to hospital for a COPD exacerbation: a prospective studyThorax20035810010512554887

- GuenetteJAJensenDWebbKAOfirDRaghavanNO’DonnellDESex differences in exertional dyspnea in patients with mild COPD: physiological mechanismsRespir Physiol Neurobiol201117721822721524719

- OfirDLavenezianaPWebbKALamYMO’DonnellDEMechanisms of dyspnea during cycle exercise in symptomatic patients with GOLD stage I chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177662262918006885

- DíazAAMoralesADíazJCCT and physiologic determinants of dyspnea and exercise capacity during the six-minute walk test in mild COPDRespir Med201310757057923313036

- ZuWallackRHow are you doing? What are you doing? Differing perspectives in the assessment of individuals with COPDCOPD2007429329717729076

- AnthonisenNRConnettJEMurrayRPSmoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 yearsAm J Respir Crit Care Med200216667567912204864

- AnthonisenNRSkeansMAWiseRAManfredaJKannerREConnettJEThe effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality: a randomized clinical trialAnn Intern Med200514223323915710956

- QaseemAWiltTJWeinbergerSEAmerican College of PhysiciansAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansAmerican Thoracic SocietyEuropean Respiratory SocietyDiagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory SocietyAnn Intern Med201115517919121810710

- O’DonnellDEAaronSBourbeauJCanadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – 2007 updateCan Respir J200714Suppl B5B32B

- ChinRCGuenetteJAChengSDoes the respiratory system limit exercise in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?Am J Respir Crit Care Med20131871315132323590271

- McDonoughJEYuanRSuzukiMSmall-airway obstruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20113651567157522029978

- NiciLDonnerCWoutersEATS/ERS Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing CommitteeAmerican Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20061731390141316760357

- PittaFTroostersTSpruitMAProbstVSDecramerMGosselinkRCharacteristics of physical activities in daily life in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200517197297715665324

- O’DonnellDEVentilatory limitations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Sci Sports Exerc200133S647S65511462073

- SaeyDMichaudACouillardAContractile fatigue, muscle morphometry, and blood lactate in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20051711109111515735055

- ManWDSolimanMGGearingJSymptoms and quadriceps fatigability after walking and cycling in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200316856256712829456

- PalangePForteSOnoratiPManfrediFSerraPCarloneSVentilatory and metabolic adaptations to walking and cycling in patients with COPDJ Appl Physiol (1985)2000881715172010797134

- PepinVSaeyDWhittomFLeBlancPMaltaisFWalking versus cycling: sensitivity to bronchodilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20051721517152216166613

- MaltaisFHamiltonAMarciniukDImprovements in symptom-limited exercise performance over 8 h with once-daily tiotropium in patients with COPDChest20051281168117816162703

- O’DonnellDEFlügeTGerkenFEffects of tiotropium on lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in COPDEur Respir J20042383284015218994

- O’DonnellDEVoducNFitzpatrickMWebbKAEffect of salmeterol on the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200424869415293609

- MatsuokaSWashkoGRDransfieldMTQuantitative CT measurement of cross-sectional area of small pulmonary vessel in COPD: correlations with emphysema and airflow limitationAcad Radiol201017939919796970

- RambodMPorszaszJMakeBJCrapoJDCasaburiRSix-minute walk distance predictors, including CT scan measures, in the COPDGene cohortChest201214186787521960696

- YuanRHoggJCParéPDPrediction of the rate of decline in FEV(1) in smokers using quantitative computed tomographyThorax20096494494919734130

- DeesomchokAWebbKAForkertLLung hyperinflation and its reversibility in patients with airway obstruction of varying severityCOPD2010742843721166631

- GagnonPGuenetteJALangerDPathogenesis of hyperinflation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014918720124600216

- HoggJCMacklemPTThurlbeckWMSite and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung diseaseN Engl J Med1968278135513605650164

- HoggJCChuFUtokaparchSThe nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20043502645265315215480

- BlackLFHyattREStubbsSEMechanism of expiratory airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with 1-antitrypsin deficiencyAm Rev Respir Dis19721058918995032709

- LeaverDGTatterfieldAEPrideNBContributions of loss of lung recoil and of enhanced airways collapsibility to the airflow obstruction of chronic bronchitis and emphysemaJ Clin Invest197352211721284727452

- MitznerWEmphysema – a disease of small airways or lung parenchyma?N Engl J Med20113651637163922029986

- CorbinRPLovelandMMartinRRMacklemPTA four-year follow-up study of lung mechanics in smokersAm Rev Respir Dis1979120293304475151

- BarberaJARamirezJRocaJWagnerPDSanchez-LloretJRodriguez-RoisinRLung structure and gas exchange in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm Rev Respir Dis19901418959012327653

- BarberàJARiverolaARocaJPulmonary vascular abnormalities and ventilation-perfusion relationships in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19941494234298306040

- Rodríguez-RoisinRDrakulovicMRodríguezDARocaJBarberàJAWagnerPDVentilation-perfusion imbalance and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease staging severityJ Appl Physiol (1985)20091061902190819372303

- SantosSPeinadoVIRamírezJCharacterization of pulmonary vascular remodelling in smokers and patients with mild COPDEur Respir J20021963263811998991

- O’DonnellDELavenezianaPOraJWebbKALamYMOfirDEvaluation of acute bronchodilator reversibility in patients with symptoms of GOLD stage I COPDThorax20096421622319052054

- O’DonnellDEMaltaisFPorszaszJLung function and exercise impairment in patients with GOLD stage I and II COPDAm J Respir Crit Care MedConference18–23 May, 2012San Francisco, California, USA Abstr. No. D80

- PeinadoVIBarberaJARamirezJEndothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arteries of patients with mild COPDAm J Physiol1998274L908L9139609729

- BorgGAPsychophysical bases of perceived exertionMed Sci Sports Exerc19821453773817154893

- McParlandCMinkJGallagherCGRespiratory adaptations to dead space loading during maximal incremental exerciseJ Appl Physiol (1985)19917055622010409

- O’DonnellDEHongHHWebbKARespiratory sensation during chest wall restriction and dead space loading in exercising menJ Appl Physiol (1985)2000881859186910797151

- SyabbaloNCZintelTWattsRGallagherCGCarotid chemoreceptors and respiratory adaptations to dead space loading during incremental exerciseJ Appl Physiol (1985)199375137813848226554

- BrownSEKingRRTemerlinSMStansburyDWMahutteCKLightRWExercise performance with added dead space in chronic airflow obstructionJ Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol198456102010266427144

- BarrRGBluemkeDAAhmedFSPercent emphysema, airflow obstruction, and impaired left ventricular fillingN Engl J Med201036221722720089972

- GrauMBarrRGLimaJAPercent emphysema and right ventricular structure and function: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis-Lung and Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis-Right Ventricle StudiesChest201314413614423450302

- MalerbaMRagnoliBSalamehMSub-clinical left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in early stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Biol Regul Homeost Agents20112544345122023769

- ManninoDMDohertyDESonia BuistAGlobal Initiative on Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classification of lung disease and mortality: findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) studyRespir Med200610011512215893923

- SabitRBoltonCEFraserAGSub-clinical left and right ventricular dysfunction in patients with COPDRespir Med20101041171117820185285

- SmithBMKawutSMBluemkeDAPulmonary hyperinflation and left ventricular mass: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis COPD StudyCirculation20131271503151123493320

- ThomashowMAShimboDParikhMAEndothelial microparticles in mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013188606823600492

- LangePMarottJLVestboJPrediction of the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, using the new GOLD classification: a study of the general populationAm J Respir Crit Care Med201218697598122997207

- RoigMEngJJMacIntyreDLRoadJDReidWDDeficits in muscle strength, mass, quality, and mobility in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev20113112012421037481

- Orozco-LeviMCoronellCRamírez-SarmientoAInjury of peripheral muscles in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseUltrastruct Pathol20123622823822849524

- van den BorstBSlotIGHellwigVALoss of quadriceps muscle oxidative phenotype and decreased endurance in patients with mild-to-moderate COPDJ Appl Physiol (1985)20131141319132822815389

- ClarkCJCochraneLMMackayEPatonBSkeletal muscle strength and endurance in patients with mild COPD and the effects of weight trainingEur Respir J200015929710678627

- SeymourJMSpruitMAHopkinsonNSThe prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD and the relationship with disease severityEur Respir J201036818819897554

- VogiatzisIZakynthinosSThe physiological basis of rehabilitation in chronic heart and lung diseaseJ Appl Physiol (1985)2013115162123620491

- PittaFTroostersTProbstVSSpruitMADecramerMGosselinkRQuantifying physical activity in daily life with questionnaires and motion sensors in COPDEur Respir J2006271040105516707399

- MooreRBerlowitzDDenehyLJacksonBMcDonaldCFComparison of pedometer and activity diary for measurement of physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev200929576119158589

- MaltaisFExercise and COPD: therapeutic responses, disease-related outcomes, and activity-promotion strategiesPhys Sportsmed201341668023445862

- Le MasurierGCTudor-LockeCComparison of pedometer and accelerometer accuracy under controlled conditionsMed Sci Sports Exerc20033586787112750599

- PittaFTroostersTSpruitMADecramerMGosselinkRActivity monitoring for assessment of physical activities in daily life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Phys Med Rehabil2005861979198516213242

- PatelSABenzoRPSlivkaWASciurbaFCActivity monitoring and energy expenditure in COPD patients: a validation studyCOPD2007410711217530503

- WatzHWaschkiBMeyerTMagnussenHPhysical activity in patients with COPDEur Respir J20093326227219010994

- WaschkiBKirstenAHolzOPhysical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort studyChest201114033134221273294

- LacasseYMartinSLassersonTJGoldsteinRSMeta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A Cochrane systematic reviewEura Medicophys20074347548518084170

- WorthHFörsterKErikssonGNihlénUPetersonSMagnussenHBudesonide added to formoterol contributes to improved exercise tolerance in patients with COPDRespir Med20101041450145920692140

- MaltaisFCelliBCasaburiRAclidinium bromide improves exercise endurance and lung hyperinflation in patients with moderate to severe COPDRespir Med201110558058721183326

- O’DonnellDECasaburiRVinckenWEffect of indacaterol on exercise endurance and lung hyperinflation in COPDRespir Med20111051030103621498063

- BorelBProvencherSSaeyDMaltaisFResponsiveness of various exercise-testing protocols to therapeutic interventions in COPDPulm Med2013201341074823431439

- BelferMHReardonJZImproving exercise tolerance and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Am Osteopath Assoc200910926827819451260

- GarrodRBestallJCPaulEAWedzichaJAJonesPWDevelopment and validation of a standardized measure of activity of daily living in patients with severe COPD: the London Chest Activity of Daily Living scale (LCADL)Respir Med20009458959610921765

- Janaudis-FerreiraTBeauchampMKRoblesPGGoldsteinRSBrooksDMeasurement of activities of daily living in patients with COPD: a systematic reviewChest201414525327123681416

- DohertyDEBelferMHBruntonSAFromerLMorrisCMSnaderTCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: consensus recommendations for early diagnosis and treatmentJ Fam Pract Clinical update200655SupplS1S8

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J20093464865419720809

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWProperties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European studyEur Respir J201138293521565915

- PowrieDJThe BODE index: a new grading system in COPDThorax200459427

- CelliBRCoteCGMarinJMThe body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20043501005101214999112

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function LaboratoriesATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk testAm J Respir Crit Care Med200216611111712091180

- SolwaySBrooksDLacasseYThomasSA qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domainChest200111925627011157613

- GolpeRPérez-de-LlanoLAMéndez-MaroteLVeres-RacamondeAPrognostic value of walk distance, work, oxygen saturation, and dyspnea during 6-minute walk test in COPD patientsRespir Care2013581329133423322886

- CasanovaCCoteCMarinJMDistance and oxygen desaturation during the 6-min walk test as predictors of long-term mortality in patients with COPDChest200813474675218625667

- Pinto-PlataVMCoteCCabralHTaylorJCelliBRThe 6-min walk distance: change over time and value as a predictor of survival in severe COPDEur Respir J200423283314738227

- IlginDOzalevliSKilincOSevincCCimrinAHUcanESGait speed as a functional capacity indicator in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Thorac Med2011614114621760846

- MorganMDSinghSJAssessing the exercise response to a bronchodilator in COPD: time to get off your bike?Thorax20076228128317387209

- SinghSJMorganMDScottSWaltersDHardmanAEDevelopment of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstructionThorax199247101910241494764

- RevillSMMorganMDSinghSJWilliamsJHardmanAEThe endurance shuttle walk: a new field test for the assessment of endurance capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax19995421322210325896

- PepinVBrodeurJLacasseYSix-minute walking versus shuttle walking: responsiveness to bronchodilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax20076229129817099077

- BrouillardCPepinVMilotJLacasseYMaltaisFEndurance shuttle walking test: responsiveness to salmeterol in COPDEur Respir J20083157958418057052

- BoerLMAsijeeGMvan SchayckOCSchermerTRHow do dyspnoea scales compare with measurement of functional capacity in patients with COPD and at risk of COPD?Prim Care Respir J20122120220722453664

- O’DonnellDEMaltaisFPorszaszJThe continuum of physiological impairment during treadmill walking in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD: patient characterization phase of a randomized clinical trialPLoS ONE201495e9657424788342

- MaltaisFDennisNChanCKRationale for earlier treatment in COPD: a systematic review of published literature in mild-to-moderate COPDCOPD2013107910323272663

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med200735677578917314337

- DecramerMCelliBKestenSLystigTMehraSTashkinDPUPLIFT investigatorsEffect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomised controlled trialLancet20093741171117819716598

- JenkinsCRJonesPWCalverleyPMEfficacy of salmeterol/fluticasone propionate by GOLD stage of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: analysis from the randomised, placebo-controlled TORCH studyRespir Res2009105919566934

- BelmanMJBotnickWCShinJWInhaled bronchodilators reduce dynamic hyperinflation during exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19961539679758630581

- O’DonnellDESciurbaFCelliBEffect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on lung hyperinflation and exercise endurance in COPDChest200613064765616963658

- PetersMMWebbKAO’DonnellDECombined physiological effects of bronchodilators and hyperoxia on exertional dyspnoea in normoxic COPDThorax20066155956716467067

- RaghavanNGuenetteJAO’DonnellDEThe role of pharmacotherapy in mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseTher Adv Respir Dis2011524525421357348

- FergusonGTMaintenance pharmacotherapy of mild and moderate COPD: what is the evidence?Respir Med20111051268127421353516

- GagnonPSaeyDProvencherSWalking exercise response to bronchodilation in mild COPD: a randomized trialRespir Med20121061695170522999808

- NiciLLareauSZuWallackRPulmonary rehabilitation in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm Fam Physician20108265566020842995

- TselebisABratisDPachiAA pulmonary rehabilitation program reduces levels of anxiety and depression in COPD patientsMultidiscip Respir Med201384123931626

- BratåsOEspnesGARannestadTWalstadRPulmonary rehabilitation reduces depression and enhances health-related quality of life in COPD patients – especially in patients with mild or moderate diseaseChron Respir Dis2010722923721084547

- ChavannesNVollenbergJJvan SchayckCPWoutersEFEffects of physical activity in mild to moderate COPD: a systematic reviewBr J Gen Pract20025257457812120732

- JácomeCIMarquesASPulmonary rehabilitation for mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic reviewRespir Care2014459458859424106321

- MartinezFJRaczekAESeiferFDCOPD-PS Clinician Working GroupDevelopment and initial validation of a self-scored COPD Population Screener Questionnaire (COPD-PS)COPD20085859518415807