Abstract

More than one third of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience comorbid symptoms of depression and anxiety. This review aims to provide an overview of the burden of depression and anxiety in those with COPD and to outline the contemporary advances and challenges in the management of depression and anxiety in COPD. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD lead to worse health outcomes, including impaired health-related quality of life and increased mortality risk. Depression and anxiety also increase health care utilization rates and costs. Although the quality of the data varies considerably, the cumulative evidence shows that complex interventions consisting of pulmonary rehabilitation interventions with or without psychological components improve symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD. Cognitive behavioral therapy is also an effective intervention for managing depression in COPD, but treatment effects are small. Cognitive behavioral therapy could potentially lead to greater benefits in depression and anxiety in people with COPD if embedded in multidisciplinary collaborative care frameworks, but this hypothesis has not yet been empirically assessed. Mindfulness-based treatments are an alternative option for the management of depression and anxiety in people with long-term conditions, but their efficacy is unproven in COPD. Beyond pulmonary rehabilitation, the evidence about optimal approaches for managing depression and anxiety in COPD remains unclear and largely speculative. Future research to evaluate the effectiveness of novel and integrated care approaches for the management of depression and anxiety in COPD is warranted.

Introduction

Prevalence and symptoms of depression and anxiety

Depression is a common mental health problem accompanied by a high degree of emotional distress and functional impairment.Citation1 The two main symptoms of major depression include depressed mood and loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities. Additional symptoms of depression include fatigue or loss of energy, significant changes in weight, appetite and sleep, guilt/worthlessness, lack of concentration, pessimism about the future, and suicidality. According to the Fifth Edition of the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a diagnosis of major depression is assigned if at least one of two main symptoms and five symptoms in total are present for at least 2 weeks and cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.Citation2,Citation3 Major depressive disorder accounted for 8.2% of years living with disability in 2010, making it the second leading direct cause of global disease burden.Citation4

Anxiety is also a common mental health problem and is associated with physical and psychological discomfort. All the anxiety disorders share common symptoms, such as fear, anxiety, and avoidance. Other anxiety-related symptoms include fatigue, restlessness, irritability, sleep disturbances, reduced concentration and memory, and muscle tension.Citation3 Among the anxiety disorders, the most common are specific or social phobias and generalized anxiety disorder.Citation5

Depression and anxiety often co-occur; it is estimated that at least half of people with depression also have anxiety. In fact, there is evidence that a mixed state of depression and anxiety is more prevalent than depression alone.Citation6 The prevalence of depression and anxiety is two to three times higher in people with chronic (long-term) medical conditions.Citation7 People with a long-term condition and depression/anxiety have worse health status than people with depression/anxiety alone, or people with any combination of long-term conditions without depression.Citation8

Prevalence of depression and anxiety in COPD

A recent meta-analysis that included 39,587 individuals with COPD and 39,431 controls found that one in four COPD patients experienced clinically significant depressive symptoms compared with less than one in eight of the controls (24.6%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 20.0–28.6 versus 11.7%, 95% CI 9.0–15.1).Citation9 These estimates are consistent with the findings of previous qualitative and quantitative reviews that assessed the prevalence of depressive symptoms in COPD.Citation10–Citation12 Clinical anxiety has also been recognized as a significant problem in COPD, with an estimated prevalence of up to 40%.Citation12,Citation13 Additionally, COPD patients are ten times more likely to experience panic disorder or panic attacks compared with general population samples.Citation14 Of note, the great variability of methods used to assess depression and anxiety in the literature makes it difficult to reach a consensus about the prevalence of depression and anxiety in COPD. Future research should quantify whether prevalence rates for depression and anxiety in COPD are significantly different among samples identified by self-rated or standardized interview methods.

The causes of depression and anxiety in COPD are likely to be multifactorial, but importantly disease severity does not appear to affect the levels of anxiety and depression in COPD patients.Citation15 Rather, subjective ratings of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), dyspnea, and reduced exercise capacity potentially underlie the development of symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD.Citation16,Citation17 Additionally, depression and anxiety are more often reported in women than in men with COPD, but differences in perceived symptom control and severity of dyspnea symptoms appear to account for this finding.Citation18,Citation19 The meta-analysis by Zhang et al showed no differences in the prevalence of depression in COPD between studies of Western and non-Western populations.Citation9 However, there is evidence that certain subgroups of British South Asians have higher rates of depression, but it is not clear what contribution somatic, genetic, or lifestyle factors play in accounting for health differentials between different ethnic groups.Citation20–Citation22 Further research is needed to examine the effects of ethnicity and nationality on the prevalence rates of depression and anxiety in COPD.

Impact of depression and anxiety on health-related quality of life

HRQoL is a multifaceted concept that is uniquely linked to health or illness, and includes a number of distinct domains corresponding to the physical, social, and psychological impact of illness.Citation23 A considerable number of published empirical studies and systematic reviews offer robust evidence that symptoms of depression and anxiety are associated with poorer HRQoL in COPD.Citation24–Citation26 However, this evidence is mainly derived from cross-sectional studies, which preclude any temporal or causal inferences being made about the association between HRQoL and depression and anxiety in COPD. A recent systematic review by Blakemore et al has examined the longitudinal impact of depression and anxiety on HRQoL. This review found that both depression and anxiety at baseline are significantly associated with worsening levels of HRQoL at 1 year follow-up (pooled r=0.48, 95% CI 0.37–0.57, P<0.001; pooled r=0.36, 95% CI 0.23–0.48, P<0.001; for depression and anxiety, respectively).Citation27 The findings of this review suggest that HRQoL may be a worthwhile target for interventions aiming to improve the psychological health of people with COPD.Citation27

Impact of depression and anxiety on health care utilization

Comorbid depression and anxiety in COPD is associated with a disproportionate increase in health care utilization rates and costs. A population-based study among people with six chronic conditions (including COPD) showed that comorbid depression doubled the likelihood of health care utilization, functional disability, and work absence.Citation28 Similarly, a US study among a managed care population showed that COPD patients with comorbid depression were 77% more likely to have a COPD-related hospitalization, 48% more likely to have an emergency room visit, and 60% more likely to have a hospitalization/emergency room visit compared with COPD patients without comorbid depression.Citation29 Other studies in this area suggest that depression in COPD leads to excessive health care utilization rates and costs, including longer hospital stay after acute exacerbation,Citation30 increased risk of exacerbation and hospital admission,Citation31,Citation32 and hospital readmission.Citation33 Comorbid anxiety and panic disorder in COPD is also associated with increased risk of exacerbations, relapse within 1 month of receiving emergency treatment,Citation34 and hospital readmission.Citation35

Evidence from systematic reviews and empirical studies suggests that the presence of mental health problems (including depression and anxiety) inflates the costs of care for long-term conditions by at least 45% after controlling for severity of physical illness.Citation36–Citation41 In COPD in particular, a recent study showed that comorbid depression and anxiety significantly inflated average annual all-cause health care costs ($23,759 versus $17,765 per patient, P<0.001) and COPD total health care costs ($3,185 versus $2,680 per patient; P<0.001).Citation29 Moreover, Howard et al found that the addition of a psychological component in a breathlessness clinic for COPD led to savings of £837 per patient 6 months after the intervention (which were mainly attributed to lower emergency room visits and fewer hospital bed days).Citation42

Impact of depression and anxiety on mortality in COPD

COPD is the fourth leading cause of morbidity worldwide and is expected to be the third leading cause of mortality by 2020.Citation43 The bulk of studies exploring mortality in patients with COPD have mainly focused on physiologic prognostic factors.Citation44 In the past decade, an increasing number of prognostic studies have indicated that mental health problems also contribute significantly to mortality risk in COPD. Depression is a particularly strong predictor for mortality in COPD (odds ratios ranging from 1.9 to 2.7)Citation30,Citation45,Citation46 and its predictive ability persists over and above the effects of other prognostic factors, including physiological factors, demographic factors, and disease severity.Citation47,Citation48 Moreover, preliminary evidence suggests that depression and anxiety interact with other risk factors (eg, physiological factors and smoking) to produce stronger combined effects on mortality risk in COPD.Citation49 On these grounds, the risk for death in COPD might be better ascertained by the simultaneous consideration of physiological and psychological prognostic factors and the awareness that the impact of these factors on mortality could be cumulative.

Managing depression and anxiety in COPD

There is a growing consensus in respiratory medicine that the therapeutic focus in COPD should move beyond disease modification and survival alone, and include assessment and improvement of patient-centered outcomes, including health status and psychological health.Citation50,Citation51 Likewise, in recognition of the increased health and economic burden associated with aging populations with long-term conditions, governments and policymakers are equally keen to promote approaches that integrate physical and mental health care, leading to improved patient outcomes, reduced unscheduled care, and reduced health care costs.Citation52 In the UK, for example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has published clinical guidelines that recommend the use of stepped approaches to psychological and/or pharmacological treatment of depression in adults in primary care;Citation53 similar guidelines have been published to underpin comparable approaches for managing depression in people with long-term conditions.Citation54 Treatments include psychological therapies based on a cognitive and behavioral framework with or without antidepressant medication.Citation55 But while there is good evidence that psychological therapies are as effective as antidepressants,Citation56 and that patients prefer psychological therapies,Citation57 treatment of depression and anxiety in people with long-term conditions is not as optimal as it could be. This is especially true in primary care where the majority of COPD patients are managed. Time-limited consultations that prioritize physical health mean that depression and anxiety remain underdetected and undertreated in people with COPD.Citation58

Outside of general practice-led primary care, the most promising intervention to meet the challenges of managing depression in people with COPD is pulmonary rehabilitation. There is growing evidence that pulmonary rehabilitation can not only improve HRQoL and exercise capacity,Citation59,Citation60 but depression and anxiety too.Citation61 The next section of this overview offers a detailed summary of the comparative effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation and other non-pharmacological interventions for managing depression in people with COPD.

Multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation

Coventry et al recently conducted a systematic review with meta-analysis that examined the comparative effects of a broad range of psychological and/or lifestyle interventions on depression and anxiety in COPD.Citation62 Interventions were divided into four subgroups: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions, multicomponent interventions with an exercise component, relaxation techniques, and self-management education. This meta-analysis included 29 randomized controlled trials and 2,063 participants, and demonstrated that the pooled effects of psychological and/or lifestyle interventions led to small but significant reductions in symptoms of depression (standardized mean difference [SMD] 0.28, 95% CI −0.41, −0.14) and anxiety (SMD −0.23, 95% CI −0.38, −0.09). When grouped according to intervention components, the only intervention associated with significant improvements in symptoms of depression (SMD −0.47, 95% CI −0.66, −0.28) and anxiety (SMD −0.45, 95% CI −0.71, −0.18) was multicomponent pulmonary rehabilitation. Cognitive and behavioral treatment approaches and relaxation techniques were associated with small but not significant reductions in depression and anxiety. Self-management interventions that included disease education did not have an effect on depression or anxiety symptoms.

When the analysis was restricted to the five trials that included both psychological and exercise components, the effect size increased to 0.64 for depression and to 0.59 for anxiety, suggesting that complex interventions containing a combination of psychological techniques and exercise training have the greatest effects on depression and anxiety.Citation62

This meta-analysis observed a great variability in the methods used to assess depression and anxiety across the studies included in the meta-analysis; some of the studies included patients with a diagnosis of depression and anxiety, while others measured symptoms of depression and anxiety (some of which did not report above threshold levels of depression). Coventry et al showed that the effectiveness of psychological and/or lifestyle interventions for reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety is equivalent across studies with confirmed depressed or above threshold samples (SMD −0.29 and −0.21 for depression and anxiety, respectively) and studies with unknown levels of depression and anxiety at baseline (SMD −0.24 and −0.27 for depression and anxiety, respectively).Citation62 Better reporting of severity of depression at baseline in clinical trials will aid more informed assessment of the impact of symptom severity on treatment outcomes.

Updated systematic review

In recognition of the expanding evidence base and the clinical importance of this area, we updated the systematic review completed by Coventry et al in 2013.Citation62

Methods

The methods used to search, select, extract, and analyze data resembled that reported in the original systematic review.Citation62 To avoid repetition, we will only briefly present some key methodological aspects of this updated systematic review.

Data sources and search strategy

All searches were initially carried out from inception to April 2012Citation62 and were updated in April 2014. The following electronic databases were searched: Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Cinahl, Web of Science, and Scopus. The above searches were complemented by hand searches of the reference lists of the included studies.

Eligibility criteria

Studies had to fulfill the following criteria to be included in the review (see Coventry et alCitation62 for more details):

Study design – cluster or individual randomized controlled trials

Population – individuals with COPD confirmed by post-bronchodilator spirometry of forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio of 70%, and a forced expiratory volume in 1 second of 80%

Intervention – single or multiple component interventions that include psychological and/or lifestyle components

Comparators – any control (eg, waiting list, usual care, attention or active control)

Outcomes – standardized measure of depression and/or anxiety.

Study selection and data extraction

The titles/abstracts and the full texts of potentially relevant studies were screened by four reviewers independently. Data were extracted using a standardized data extraction form. Extracted data included characteristics of patients, interventions, outcomes, and quality appraisal of the studies. Study authors were contracted to retrieve data not available in published reports. Any disagreements during the process of study selection and data extraction were resolved by consensus in group meetings with all review authors.

Data analysis

Meta-analyses using random effects models were undertaken to assess the effectiveness of different types of complex interventions on reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety in those with COPD. Effect sizes were expressed as the SMD; an SMD of 0.56–1.2 is large, SMD 0.33–0.55 is moderate, and SMD of <0.32 is small.Citation63 Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2, which provides a quantitative measure of the degree of between-study differences caused by factors other than sampling error; higher I2 rates indicate higher heterogeneity.Citation64

Results

The updated searches yielded 736 citations excluding duplicates. Of these, 714 citations were excluded at the title and abstract screening stage. The full texts for 22 citations were retrieved and checked against the eligibility criteria of the review. Following full-text screening, we identified five additional studies (providing six relevant comparisons) as eligible for inclusion in the review.

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 34 studies that provided 36 relevant comparisons (n=2,577) were included in the updated meta-analysis. The COPD patients had a median age of 66 years with an equal sex distribution. The severity of COPD ranged from moderate to severe across the majority of the studies (see for patient characteristics).

Table 1 Characteristics of the study populations

The majority of studies (80%) evaluated complex interventions that included both psychological and lifestyle components, while six included only psychological components, and four lifestyle interventions alone. Among the five trials identified from the new searches, two studies (including three comparisons) comprised multicomponent exercise interventionsCitation65,Citation66 and three studies comprised CBT interventions.Citation67–Citation69 None of the new trials evaluated relaxation techniques or self-management interventions (see for intervention characteristics).

Table 2 Characteristics of the interventions

Effects of different types of complex interventions on depression and anxiety

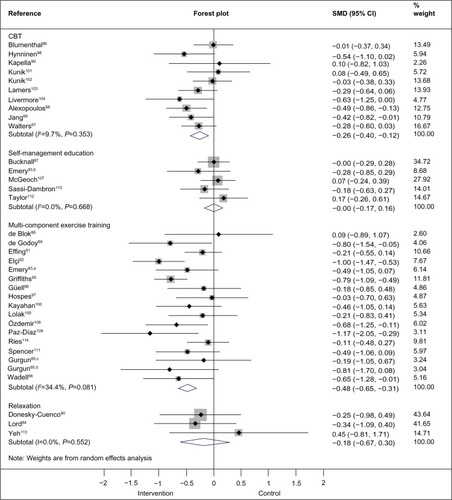

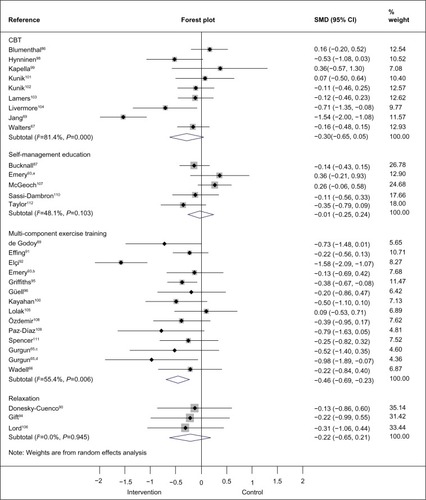

Thirty-four trials reported data on depression and 30 trials reported data on anxiety. As with the results of the original review,Citation62 the pooled effects of the interventions indicated small but significant improvements in depression (SMD −0.30, 95% CI −0.41, −0.19) and in anxiety (SMD −0.31, 95% CI −0.49, −0.10). Subgroup analysis showed that CBT interventions were associated with small and significant improvements in depression. The results for the subgroup of multicomponent exercise training interventions were unchanged; multicomponent exercise training interventions were associated with the largest treatment effects in favor of a reduction in depression and anxiety (forest plot, and ).

Figure 1 Effects of subgroups of complex interventions on self-reported depression at post-treatment.

Note: Random-effects model was used. aIndependent comparison 1, exercise, education, and stress management; bindependent comparison 2, education and stress management; cindependent comparison 1, pulmonary rehabilitation and nutritional support; dindependent comparison 2, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive and behavioral therapy; CI, confidence interval; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Figure 2 Effects of subgroups of complex interventions on self-reported anxiety at post-treatment.

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive and behavioral therapy; CI, confidence interval; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Implications for practice and research

Multicomponent exercise training with or without psychological support is associated with the greatest improvements in symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD compared with other nonpharmacological approaches. Components of pulmonary rehabilitation vary, but typically include prescribed supervised exercise training and self-management advice as well as multidisciplinary education about COPD and nutrition for a minimum of 6 weeks. Psychological and behavioral interventions may also be provided in the context of self-management advice, with an emphasis on promoting adaptive behaviors such as self-efficacy.Citation51 However, psychological interventions are rarely provided alongside or integrated within pulmonary rehabilitation.Citation70 Future research could address whether mental health professionals, in collaboration with multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation teams, could play important roles in the delivery of psychological interventions for common mental health problems in COPD patients attending pulmonary rehabilitation.

Interventions based on a CBT format are also potentially effective for managing depression in COPD. These results are consistent with other meta-analyses showing that psychological interventions that include CBT significantly reduce symptoms of depression in people with long-term conditions.Citation71,Citation72 However, the size of the treatment effects associated with CBT in populations with long-term conditions are small and possibly of trivial importance for patients. Existing evidence about the beneficial effects of CBT in anxiety disordersCitation73 and in other long-term conditionsCitation74 implies that unique features of COPD might account for the relatively small treatment effects for CBT in this patient group. For instance, the use of CBT techniques to counter ruminative thinking and avoidance behaviors might not be acceptable to COPD patients when these behaviors are triggered as a response to real and meaningful COPD symptoms such as dyspnea.Citation62 Alternative or “third wave” psychological therapies that target the process of thoughts (rather than their content, as in CBT) and help people to become aware of their thoughts and accept them in a nonjudgmental way are equally effective for depression as CBT.Citation75 Mindfulness meditation is associated with longer-term mental health benefits when compared with relaxation aloneCitation76 and is acceptable among people with long-term conditions,Citation77 but its effectiveness among COPD patients has not yet been confirmed.Citation78

Other explanations for why stand-alone interventions such as CBT may only confer modest benefits in people with COPD point to the need to embed psychological interventions within collaborative and multidisciplinary frameworks that promote proactive case management of patients and supervision of psychological therapists. Collaborative care is a complex intervention that typically involves a case manager working in conjunction with the patient’s physician (usually their primary care physician), often with the support and supervision of a mental health specialist (a psychiatrist or psychologist). When compared with usual care, collaborative care is associated with significant improvement in depression and anxiety outcomes over the short-, medium-, and long-term.Citation75 There is also evidence that collaborative care can improve both physical and mental health in people with long-term conditions.Citation79 However, there is less evidence that collaborative interventions are effective in COPD, and trials to date have focused on self-management interventions to reduce exacerbations and improve medication adherence in acute illness, not on reducing depression or anxiety.Citation80,Citation81

In this overview, we have focused on the benefits of non-pharmacological interventions for the management of depression and anxiety in COPD. Psychological interventions are as effective as drug therapies for improving the psychological ill health of patients with COPD and are rated as preferable to drug therapies by patients.Citation57,Citation82 Additionally, psychological interventions with or without medication have been recommended for managing depression and anxiety in COPD.Citation55 To date, the levels of evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological interventions in reducing depression and anxiety in COPD are limited. Two recent reviews suggested that no firm conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants) in reducing depression in COPD because there are only a small number of published trials in this area, many of which have important methodological limitations, such as small sample sizes, and high dropout rates.Citation83,Citation84

Conclusion and future directions

There is ample research evidence that depression and anxiety are important determinants of health outcomes and health care utilization in COPD. Health care policy has highlighted the need to manage depression and anxiety in long-term conditions, including COPD, but finding effective and innovative ways of implementing existing treatments remains a major challenge. Contemporary research suggests that complex psychological and/or lifestyle interventions which include a pulmonary rehabilitation component have the greatest effects on depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. However, further work is needed to understand how exercise improves anxious and depressed moods in COPD. Additionally, CBT appears to be effective in improving depression in COPD, but its benefits could be enhanced if embedded within collaborative care models that integrate physical and mental health care. Collaborative care models that focus on building partnerships between mental health and other professionals to foster integration of care for people with complex morbidities present a fruitful framework for the management of mental health in COPD. In particular, the integration of pulmonary rehabilitation and psychological therapies such as CBT has the potential to lead to significant patient benefits. Moreover, further research into ways to target markers of psychological health such as HRQoL could advance the clinical management of mental health in COPD.

In conclusion, finding ways to strengthen the delivery of effective mental health care within the context of innovative chronic disease management programs such as pulmonary rehabilitation in primary care offer opportunities to meet the challenge set out by the World Health Organization that there can be “no health without mental health”.Citation85

Acknowledgments

PC is funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Greater Manchester. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research, National Health Service, or the Department of Health. We thank Liz Baker and Dr Cassandra Kenning for supporting searches and the data extraction included in the updated review presented in this paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Ayuso-MateosJLVazquez-BarqueroJLDowrickCDepressive disorders in Europe: prevalence figures from the ODIN studyBr J Psychiatry200117930831611581110

- UherRPayneJLPavlovaBPerlisRHMajor depressive disorder in DSM-5: implications for clinical practice and research of changes from DSM-IVDepress Anxiety201431645947124272961

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders5th edArlington, VA, USAAmerican Psychiatric Publishing2013

- FerrariAJCharlsonFJNormanREBurden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010PLoS Med20131011e100154724223526

- KesslerRCPetukhovaMSampsonNAZaslavskyAMWittchenHUTwelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United StatesInt J Methods Psychiatr Res201221316918422865617

- TyrerPThe case for cothymia: mixed anxiety and depression as a single diagnosisBr J Psychiatry200117919119311532793

- KatonWJEpidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illnessDialogues Clin Neurosci201113172321485743

- MoussaviSChatterjiSVerdesETandonAPatelVUstunBDepression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health SurveysLancet2007370959085185817826170

- ZhangMWHoRCCheungMWFuEMakAPrevalence of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regressionGen Hosp Psychiatry201133321722321601717

- van EdeLYzermansCJBrouwerHJPrevalence of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewThorax199954868869210413720

- ManninoDMBuistASGlobal burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trendsLancet2007370958976577317765526

- KunikMERoundyKVeazeyCSurprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disordersChest200512741205121115821196

- WillgossTGYohannesAMAnxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic reviewRespir Care201358585886622906542

- LivermoreNSharpeLMcKenzieDPanic attacks and panic disorder in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cognitive behavioral perspectiveRespir Med201010491246125320457513

- WagenaEJArrindellWAWoutersEFvan SchayckCPAre patients with COPD psychologically distressed?Eur Respir J200526224224816055871

- LouPZhuYChenPPrevalence and correlations with depression, anxiety, and other features in outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a cross-sectional case control studyBMC Pulm Med2012125322958576

- HananiaNAMullerovaHLocantoreNWDeterminants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183560461120889909

- Di MarcoFVergaMReggenteMAnxiety and depression in COPD patients: The roles of gender and disease severityRespir Med2006100101767177416531031

- LaurinCLavoieKLBaconSLSex differences in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and psychological distress in patients with COPDChest2007132114815517505033

- BhuiKBhugraDGoldbergDSauerJTyleeAAssessing the prevalence of depression in Punjabi and English primary care attenders: the role of culture, physical illness and somatic symptomsTranscult Psychiatry200441330732215551723

- GaterRTomensonBPercivalCPersistent depressive disorders and social stress in people of Pakistani origin and white Europeans in UKSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200944319820718726242

- WeichSNazrooJSprostonKCommon mental disorders and ethnicity in England: the EMPIRIC studyPsychol Med20043481543155115724884

- BakasTMcLennonSMCarpenterJSSystematic review of health-related quality of life modelsHealth Qual Life Outcomes20121013423158687

- Martinez FrancesMEPerpina TorderaMBelloch FusterAMartinez MoragonEMCompte TorreroLImpact of baseline and induced dyspnea on the quality of life of patients with COPDArch Bronconeumol2008443127134 Spanish18361883

- BalcellsEGeaJFerrerJFactors affecting the relationship between psychological status and quality of life in COPD patientsHealth Qual Life Outcomes2010810820875100

- TsiligianniIGvan der MolenTA systematic review of the role of vitamin insufficiencies and supplementation in COPDRespir Res20101117121134250

- BlakemoreADickensCGuthrieEDepression and anxiety predict health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014950151224876770

- SteinMBCoxBJAfifiTOBelikSLSareenJDoes co-morbid depressive illness magnify the impact of chronic physical illness? A population-based perspectivePsychol Med200636558759616608557

- DalalAAShahMLunacsekOHananiaNAClinical and economic burden of depression/anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients within a managed care populationCOPD20118429329921827298

- NgTPNitiMTanWCCaoZOngKCEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med20071671606717210879

- LaurinCMoullecGBaconSLLavoieKLImpact of anxiety and depression on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation riskAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012185991892322246177

- XuWColletJPShapiroSIndependent effect of depression and anxiety on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations and hospitalizationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178991392018755925

- CoventryPAGemmellIToddCJPsychosocial risk factors for hospital readmission in COPD patients on early discharge services: a cohort studyBMC Pulm Med2011114922054636

- DahlenIJansonCAnxiety and depression are related to the outcome of emergency treatment in patients with obstructive pulmonary diseaseChest200212251633163712426264

- GudmundssonGGislasonTJansonCRisk factors for rehos-pitalisation in COPD: role of health status, anxiety and depressionEur Respir J200526341441916135721

- HochlehnertANiehoffDWildBJungerJHerzogWLoweBPsychiatric comorbidity in cardiovascular inpatients: costs, net gain, and length of hospitalizationJ Psychosom Res201170213513921262415

- HutterNSchnurrABaumeisterHHealth care costs in patients with diabetes mellitus and comorbid mental disorders – a systematic reviewDiabetologia201053122470247920700575

- GilmerTPO’ConnorPJRushWAPredictors of health care costs in adults with diabetesDiabetes Care2005281596415616234

- SimonGEKatonWJLinEHCost-effectiveness of systematic depression treatment among people with diabetes mellitusArch Gen Psychiatry2007641657217199056

- CiechanowskiPSKatonWJRussoJEDepression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costsArch Intern Med2000160213278328511088090

- NaylorCParsonageMMcDaidDKnappMFosseyMGaleaALong-Term Conditions and Mental Health. The Cost of Co-MorbiditiesLondon, UKThe Kings Fund2012

- HowardCDupontSHaseldenBLynchJWillsPThe effectiveness of a group cognitive-behavioural breathlessness intervention on health status, mood and hospital admissions in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychol Health Med201015437138520677076

- ManninoDMKirizVAChanging the burden of COPD mortalityInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20061321923318046859

- EstebanCQuintanaJMMorazaJBODE-Index vs HADO-score in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: which one to use in general practice?BMC Med201082820497527

- GroenewegenKHScholsAMWoutersEFMortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPDChest2003124245946712907529

- AlmagroPCalboEOchoa de EchaguenAMortality after hospitalization for COPDChest200212151441144812006426

- FanVSRamseySDGiardinoNDSex, depression, and risk of hospitalization and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med2007167212345235318039994

- de VoogdJNWempeJBKoëterGHDepressive symptoms as predictors of mortality in patients with COPDChest2009135361962519029432

- LouPChenPZhangPEffects of smoking, depression, and anxiety on mortality in COPD patients: a prospective studyRespir Care2014591546123737545

- RocheNWhere current pharmacological therapies fall short in COPD: symptom control is not enoughEur Respir Rev20071698104

- SpruitMASinghSJGarveyCAn Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20131888e13e6424127811

- PrinceMPatelVSaxenaSNo health without mental healthLancet2007370959085987717804063

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceThe Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition)NICE Clinical Guidelines, No 90Leicester, UKBritish Psychological Society2010 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63748/Accessed September 19, 2014

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceDepression in adults with a chronic physical health problem. Treatment and managementLondon, UKNational Institute for Health and Care Excellence2009 Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg91Accessed September 19, 2014

- Department of HealthAn outcomes strategy for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma in EnglandLondon, UKDepartment of Health2011 Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/an-outcomes-strategy-for-people-with-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd-and-asthma-in-englandAccessed September 19, 2014

- CuijpersPSijbrandijMKooleSLAnderssonGBeekmanATReyn-oldsCF3rdThe efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of direct comparisonsWorld Psychiatry201312213714823737423

- McHughRKWhittonSWPeckhamADWelgeJAOttoMWPatient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic reviewJ Clin Psychiatry201374659560223842011

- CoventryPAHaysRDickensCTalking about depression: a qualitative study of barriers to managing depression in people with long term conditions in primary careBMC Fam Pract20111012

- LacasseYGoldsteinRLassersonTJMartinSPulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20064CD00379317054186

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (update)Clinical guideline 101London, UKNational Institute for Health and Care Excellence2010 Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101Accessed September 19, 2014

- CoventryPADoes pulmonary rehabilitation reduce anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?Curr Opin Pulm Med200915214314919532030

- CoventryPABowerPKeyworthCThe effect of complex interventions on depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS One201384e6053223585837

- LipseyMWWilsonDBThe efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment. Confirmation from meta-analysisAm Psychol19934812118112098297057

- HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDGMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysesBMJ2003327741455756012958120

- GurgunADenizSArginMKarapolatHEffects of nutritional supplementation combined with conventional pulmonary rehabilitation in muscle-wasted chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective, randomized and controlled studyRespirology201318349550023167516

- WadellKWebbKAPrestonMEImpact of pulmonary rehabilitation on the major dimensions of dyspnea in COPDCOPD201310442543523537344

- WaltersJCameron-TuckerHWillsKEffects of telephone health mentoring in community-recruited chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on self-management capacity, quality of life and psychological morbidity: a randomised controlled trialBMJ Open201339e003097

- AlexopoulosGSKiossesDNSireyJAPersonalised intervention for people with depression and severe COPDBr J Psychiatry2013202323523623391728

- JiangXHeGEffects of an uncertainty management intervention on uncertainty, anxiety, depression, and quality of life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease outpatientsRes Nurs Health201235440941822511399

- RobertsCStoneRPurseyNPotterJO’ReillyJThe national chronic obstructive pulmonary disease resources and outcomes project (NCROP)London, UK2010 Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/ncrop-re-survey-report-nov-2010_0.pdfAccessed September 19, 2014

- HarknessEMacdonaldWValderasJCoventryPGaskLBowerPIdentifying psychosocial interventions that improve both physical and mental health in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysisDiabetes Care201033492693020351228

- DickensCCherringtonAAdeyemiICharacteristics of psychological interventions that improve depression in people with coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-regressionPsychosom Med201375221122123324874

- ButlerACChapmanJEFormanEMBeckATThe empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analysesClin Psychol Rev2006261173116199119

- BeltmanMWVoshaarRCSpeckensAECognitive-behavioural therapy for depression in people with a somatic disease: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsBr J Psychiatry20101971111920592427

- ArcherJBowerPGilbodySCollaborative care for depression and anxiety problemsCochrane Database Syst Rev201210CD00652523076925

- JainSShapiroSLSwanickSA randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distractionAnn Behav Med2007331112117291166

- KeyworthCKnoppJRoughleyKDickensCBoldSCoventryPA Mixed-methods pilot study of the acceptability and effectiveness of a brief meditation and mindfulness intervention for people with diabetes and coronary heart diseaseBehav Med2013402536424754440

- MularskiRAMunjasBALorenzKARandomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based therapy for dyspnea in chronic obstructive lung diseaseJ Altern Complement Med200915101083109019848546

- KatonWJLinEHVon KorffMCollaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnessesN Engl J Med2010363272611262021190455

- FanVSGazianoJMLewRA comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trialAnn Intern Med20121561067368322586006

- RiceKLDewanNBloomfieldHEDisease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182789089620075385

- YohannesAMConnollyMJBaldwinRCA feasibility study of antidepressant drug therapy in depressed elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200116545145411376459

- FritzscheAClamorAvon LeupoldtAEffects of medical and psychological treatment of depression in patients with COPD – a reviewRespir Med2011105101422143321680167

- HegerlUMerglRDepression and suicidality in COPD: understandable reaction or independent disorders?Eur Respir J201444373474324876171

- World Health OrganizationMental health: facing the challenges, building solutionsReport from the WHO European Ministerial ConferenceCopenhagen, Denmark2005 Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/96452/E87301.pdfAccessed September 19, 2014

- BlumenthalJABabyakMAKeefeFJTelephone-based coping skills training for patients awaiting lung transplantationJ Consult Clinical Psychol200674353554416822110

- BucknallCEMillerGLloydSMGlasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trialBMJ2012344e106022395923

- de BlokBMde GreefMHten HackenNHSprengerSRPostemaKWempeJBThe effects of a lifestyle physical activity counseling program with feedback of a pedometer during pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: a pilot studyPatient Educ Couns2006611485516455222

- de GodoyDVde GodoyRFA randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Phys Med Rehabil20038481154115712917854

- Donesky-CuencoDNguyenHQPaulSCarrieri-KohlmanVYoga therapy decreases dyspnea-related distress and improves functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot studyJ Altern Complement Med200915322523419249998

- EffingTZielhuisGKerstjensHvan der ValkPvan der PalenJCommunity based physiotherapeutic exercise in COPD self-management: a randomised controlled trialRespir Med2011105341842620951018

- ElçiABörekçiSOvayoluNElbekOThe efficacy and applicability of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme for patients with COPD in a secondary-care community hospitalRespirology200813570370718713091

- EmeryCFScheinRLHauckERMacIntyreNRPsychological and cognitive outcomes of a randomized trial of exercise among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychol1998173232240

- GiftAGMooreTSoekenKRelaxation to reduce dyspnea and anxiety in COPD patientsNurs Res19924142422461408866

- GriffithsTLResults at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trialLancet20003559211128010770337

- GuellRResquetiVSangenisMImpact of pulmonary rehabilitation on psychosocial morbidity in patients with severe COPDChest2006129489990416608936

- HospesGBossenbroekLten HackenNHvan HengelPde GreefMHEnhancement of daily physical activity increases physical fitness of outclinic COPD patients: results of an exercise counseling programPatient Educ Couns200975227427819036552

- HynninenMJBjerkeNPallesenSBakkePSNordhusIHA randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in COPDRespir Med2010104798699420346640

- KapellaMCHerdegenJJPerlisMLCognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia comorbid with COPD is feasible with preliminary evidence of positive sleep and fatigue effectsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011662563522162648

- KayahanBKarapolatHAtýntoprakEAtaseverAOztürkOPsychological outcomes of an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med200610061050105716253496

- KunikMEBraunUStanleyMAOne session cognitive behavioural therapy for elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychol Med200131471772311352373

- KunikMEVeazeyCCullyJACOPD education and cognitive behavioral therapy group treatment for clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD patients: a randomized controlled trialPsychol Med200838338539617922939

- LamersFJonkersCCBosmaHChavannesNHKnottnerusJAvan EijkJTImproving quality of life in depressed COPD patients: effectiveness of a minimal psychological interventionCOPD20107531532220854045

- LivermoreNSharpeLMcKenzieDPrevention of panic attacks and panic disorder in COPDEur Respir J201035355756319741029

- LolakSConnorsGLSheridanMJWiseTNEffects of progressive muscle relaxation training on anxiety and depression in patients enrolled in an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programPsychother Psychosom200877211912518230945

- LordVMCavePHumeVJSinging teaching as a therapy for chronic respiratory disease - a randomised controlled trial and qualitative evaluationBMC Pulm Med2010104120682030

- McGeochGRBWillsmanKJDowsonCASelf-management plans in the primary care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespirology200611561161816916335

- OzdemirEPSolakOFidanFThe effect of water-based pulmonary rehabilitation on anxiety and quality of life in chronic pulmonary obstructive disease patients. Turk Klin Tip BilimJun2010303880887

- Paz-DiazHMontes de OcaMLópezJMCelliBRPulmonary rehabilitation improves depression, anxiety, dyspnea and health status in patients with COPDAm J Phys Med Rehabil2007861303617304686

- Sassi-DambronDEEakinEGRiesALKaplanRMTreatment of dyspnea in COPD. A controlled clinical trial of dyspnea management strategiesChest199510737247297874944

- SpencerLMAlisonJAMcKeoughZJMaintaining benefits following pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trialEur Respir J201035357157719643944

- TaylorSJCSohanpalRBremnerSADevineAEldridgeSGriffithsCJPilot randomised controlled trial of a 7-week disease-specific self-management programme for patients with COPD: BELLA (Better Living with Long term Airways disease study)Thorax200964A95A97

- YehGYRobertsDHWaynePMDavisRBQuiltyMTPhillipsRSTai chi exercise for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot studyRespir Care201055111475148220979675

- RiesALKaplanRMLimbergTMPrewittLMEffects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Int Med1995122118238327741366