Abstract

Introduction

Our understanding of how comorbid diseases influence health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is limited and in need of improvement. The aim of this study was to examine the associations between comorbidities and HRQL as measured by the instruments EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D) and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT).

Methods

Information on patient characteristics, chronic bronchitis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, renal impairment, musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, depression, and EQ-5D and CAT questionnaire results was collected from 373 patients with Forced Expiratory Volume in one second (FEV1) <50% of predicted value from 27 secondary care respiratory units in Sweden. Correlation analyses and multiple linear regression models were performed using EQ-5D index, EQ-5D visual analog scale (VAS), and CAT scores as response variables.

Results

Having more comorbid conditions was associated with a worse HRQL as assessed by all instruments. Chronic bronchitis was significantly associated with a worse HRQL as assessed by EQ-5D index (adjusted regression coefficient [95% confidence interval] −0.07 [−0.13 to −0.02]), EQ-5D VAS (−5.17 [−9.42 to −0.92]), and CAT (3.78 [2.35 to 5.20]). Musculoskeletal symptoms were significantly associated with worse EQ-5D index (−0.08 [−0.14 to −0.02]), osteoporosis with worse EQ-5D VAS (−4.65 [−9.27 to −0.03]), and depression with worse EQ-5D index (−0.10 [−0.17 to −0.04]). In stratification analyses, the associations of musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, and depression with HRQL were limited to female patients.

Conclusion

The instruments EQ-5D and CAT complement each other and emerge as useful for assessing HRQL in patients with COPD. Chronic bronchitis, musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, and depression were associated with worse HRQL. We conclude that comorbid conditions, in particular chronic bronchitis, depression, osteoporosis, and musculoskeletal symptoms, should be taken into account in the clinical management of patients with severe COPD.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by a limitation of expiratory air flow that is not fully reversible.Citation1 In chronic diseases like COPD, health-related quality of life (HRQL) has been perceived as an important patient-oriented measure. According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommendations, diagnosis and monitoring of COPD should include assessment of health status and symptoms.Citation1

HRQL can be assessed by generic and/or disease-specific instruments.Citation2 The generic instruments 36-item short form health survey (SF-36),Citation3 12-item short form health survey (SF-12),Citation4 and the EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D)Citation5 have all previously been used in COPD patients. Among disease-specific instruments, the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)Citation6 has been considered the gold standard for assessment of HRQL in patients with COPD. However, more recently, the shorter but clinically more useful health status instrument, COPD Assessment Test (CAT),Citation7 has been recommended for assessing the influence of COPD on health status and everyday activities. The outcomes of CAT and SGRQ show a fairly good correlation in patients with COPD.Citation7

Many COPD patients suffer from more than one condition,Citation8 and comorbidities are known to influence mortality, morbidity, and hospitalizations as well as HRQL.Citation9–Citation11 The associations of cardiovascular disease, depression, and underweight with poor HRQL are well documented,Citation12–Citation15 although our understanding of these associations remains limited. The same applies to the associations between COPD and several other comorbidities, which is why further studies of their influence on HRQL in COPD are needed.

In Sweden, the majority of patients with COPD are managed in primary care. Those COPD patients who are managed at the secondary care level, although fewer in number, are more likely to include patients with severe disease, more comorbidities, and worse HRQL.Citation14,Citation16 The main aim of the present study was to determine the HRQL in patients with severe COPD at secondary care respiratory units in Sweden and to characterize the influence of comorbidities on health status, everyday activities, and HRQL in these patients as assessed by the CAT and EQ-5D instruments.

Methods

Data collection

Sweden has 33 hospital-based secondary care respiratory units, including departments of respiratory medicine or sections of respiratory medicine that form parts of departments of internal medicine. All 33 units were invited to participate in the present study. Each respiratory unit was asked to enroll consecutively a maximum of 10 patients with GOLD stage III COPD and five with GOLD stage IV COPDCitation1 during the period from May 12, 2011, to March 28, 2012, approximately matching the distribution of severe and very severe COPD in the general population.Citation14,Citation16 During the patients’ visits, information was collected by the physician responsible for the study center on sex, age, smoking history and habits, body weight and height, influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status, current pharmacological treatment, number of exacerbations, and health care visits within the past year. The responsible physicians also noticed if the patients had symptoms indicating chronic bronchitis, and whether pharmacologically or nonpharmacologically treated cardiovascular disease, diabetes, renal impairment, malnutrition, obesity/overweight, musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, or depression was present. Examples of nonpharmacological treatment are physiotherapy for musculoskeletal symptoms, cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, or diet-treated diabetes.

The information was entered in the study case record form together with data from the most recently performed spirometry. Post-bronchodilator values were used, but pre-bronchodilator values were substituted if post-bronchodilator values were missing. In addition, each patient completed the Swedish versions of EQ-5D and CAT either immediately during the visit or later at home. The basis for choosing EQ-5D and CAT was an intention to investigate brief and clinically convenient instruments and to get a more comprehensive view by using both generic and disease-specific questionnaires. The only exclusion criterion was an inability to complete the study on language grounds.

EuroQol-5 dimension

The EQ-5D questionnaire is a standardized, preference-based instrument intended for use as a general measure of health status.Citation5 As the name implies, it includes five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has three levels, where level 1 indicates no problems, level 2 some problems, and level 3 extreme problems. The answers to the five items constitute a health profile, which can be transformed into a single summary index (EQ-5D index). The present study used weights from the UK algorithm,Citation17 where the EQ-5D index can range from −0.6 to 1.0. The EQ-5D instrument also includes a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100 (EQ-5D VAS) for respondents to self-rate their health, with 100 denoting the best and 0 the worst imaginable health status.

COPD Assessment Test

The CAT form includes eight items describing the presence or absence of cough, mucus production, chest tightness, effort dyspnea, limitation of activities at home, sense of confidence about leaving the home, sleep, and energy. The symptoms are assessed on a six-point scale from 0 to 5. The main outcome measure is the total score, where 0 indicates the absence of any negative influence of disease and 40 the worst imaginable health status.Citation7

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using PASW version 20.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS software version 9.3 for Windows (copyright © 2002–2010; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and classified into groups defined as BMI <22, BMI ≥22 but <30, and BMI ≥30. The cut-off values were chosen based on previous knowledge about the prognostic value of BMI in COPD.Citation18 The number of COPD exacerbations in the preceding 12-month period was classified as 0, 1, 2, or more. The EQ-5D index was calculated. Patient characteristics were tabulated to investigate potential differences between male and female patients. Student’s t-test was used to investigate differences in mean values of age, number of pack years, FEV1 as a percentage of predicted value (FEV1% pred), EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS and CAT, and the χ2 test to investigate differences in sex, smoking status, COPD stage, BMI (three groups), exacerbations (three groups), and comorbidities. The associations between EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score and CAT score, and the number of comorbid conditions (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, renal impairment, musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, and depression) were analyzed. Correlation analyses between EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS and CAT scores were performed. Separate multiple linear regression analyses using chronic bronchitis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, renal impairment, musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, and depression as explanatory variables, and EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score, and CAT score as response variables were performed with adjustment for age, sex, number of pack years, FEV1% pred BMI, and number of exacerbations. Starting from an initial model with all independent variables, stepwise regression resulted in a final model for each response variable including the remaining variables with statistically significant associations with HRQL. Stepwise regression for EQ-5D index as response variable resulted in a final model including sex, age, FEV1% pred chronic bronchitis, musculoskeletal symptoms, depression, and number of exacerbations. Stepwise regression for EQ-5D VAS as response variable resulted in a final model including sex, chronic bronchitis, and osteoporosis. Stepwise regression for CAT as response variable resulted in a final model including sex, FEV1% pred chronic bronchitis, and number of exacerbations. Stratification and interaction analyses were used to investigate differences between the sexes. Separate interaction analyses investigated potential modification of effect by sex for the different HRQL scores, using interaction terms for sex with chronic bronchitis, musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, and depression with adjustment for the variables in the respective final models. In all analyses, a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The study was conducted as a noninterventional trial, in accordance with European Union directive 2001/20/EC and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Umeå University (Dnr 2011-10-31M). Written consent was given by all patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

Data from 27 respiratory units were included in the analyses. Six units declined participation due to lack of resources. In total, data were collected from 383 patients. Of these, 10 patients did not fulfill the inclusion criterion of a FEV1 <50% of predicted value and were excluded from further analyses. Post-bronchodilator values were missing for 161 patients and were replaced with pre-bronchodilator values. Based on the available values and presence of hypoxia, 259 had COPD stage III and 114 had COPD stage IV.Citation1

Patient characteristics including mean values of the HRQL response variables EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score, and CAT score are summarized in . Male patients had a higher cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke (higher number of pack years) and more frequently had cardiovascular disease. Underweight (BMI ≤22), osteoporosis, musculoskeletal symptoms, and depression were more common in female patients. Women also were of younger age and had more frequent exacerbations (≥2 in the past year) and worse HRQL as assessed by EQ-5D index and CAT, compared with men.

Number of comorbidities and HRQL

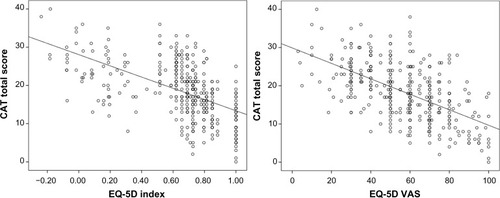

The number of comorbid conditions for which patients were receiving pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatment ranged from 1 to 4. There was a clear association between a larger number of comorbid conditions and worse HRQL, as assessed by all HRQL instruments ().

Figure 1 Comorbidity score and health-related quality of life. Unadjusted mean EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score, and CAT total score in relation to the number of treated comorbid conditions.

Correlation analyses

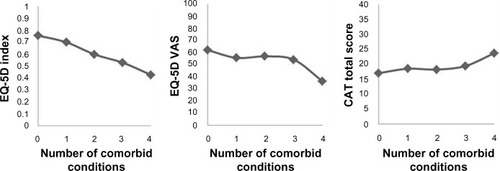

The correlations between EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score, and CAT score were all statistically significant. There was a negative correlation between CAT score and EQ-5D index (r=−0.56, P<0.0001) and between CAT score and EQ-5D VAS (r=−0.58, P<0.0001) (), whereas EQ-5D index and EQ-5D VAS were positively correlated (r=0.50, P<0.0001).

Multiple linear regression analyses

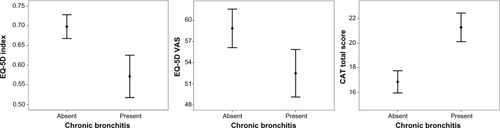

The results of multiple linear regression analysis, with EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score, and CAT score as response variables, are presented in and in the online Supplementary Table S1. Sex (female), high age, lower FEV1% pred, frequent exacerbations, current chronic bronchitis, musculoskeletal symptoms, and depression were associated with a worse HRQL as assessed by the EQ-5D index. Lower FEV1% pred, chronic bronchitis, and osteoporosis were associated with a worse HRQL as assessed by EQ-5D VAS. Sex (female), lower FEV1% pred, frequent exacerbations and chronic bronchitis were related to a lower HRQL as estimated by a higher CAT score. No statistically significant associations with HRQL were found for cardiovascular disease. shows the differences in unadjusted mean values of HRQL as measured by EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS, and CAT in patients with and without chronic bronchitis.

Table 1 Patient characteristics

Table 2 Associations between HRQL response variables and explanatory variables

Figure 3 Chronic bronchitis and health-related quality of life. Unadjusted mean EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score, and CAT total score (with 95% confidence intervals) in patients with and without chronic bronchitis.

Sex-related differences

Sex (female) was associated with worse HRQL as assessed by both EQ-5D-index and CAT. Stratification by sex showed that chronic bronchitis was associated with HRQL as assessed by CAT in both sexes, and with the EQ-5D index assessment in women (). In women, musculoskeletal symptoms and depression were associated with EQ-5D index and osteoporosis with EQ-5D VAS score. However, there were no statistically significant sex-related differences in the associations between comorbidities and HRQL ().

Table 3 Associations between comorbid conditions and HRQL by patient sex

Discussion

The most important finding was that comorbidities influence HRQL in patients with severe and very severe COPD in secondary care, with a clear gradient of worse HRQL in patients with more comorbid conditions. The results show that chronic bronchitis was the only explanatory variable associated with all three HRQL response variables, EQ-5D index, EQ-5D VAS score, and CAT score.

Chronic bronchitis is commonly defined as cough and phlegm most days for at least 3 months during a minimum of 2 consecutive years.Citation1 Chronic bronchitis in COPD patients can be regarded as a comorbid condition or as a specific phenotype of COPD. The rationale for this is that a “COPD phenotype” has been defined as “a single or combination of disease attributes that describe differences between individuals with COPD as they relate to clinically meaningful outcomes”.Citation19 Recently, the existence of three different COPD phenotypes was proposed: the emphysematous phenotype, the chronic bronchitis phenotype, and the COPD–asthma phenotype with a history of asthma.Citation20 In line with this, the COPDGene Study characterized COPD patients with chronic bronchitis as younger, more frequently current smokers, with a history of a higher cumulative exposure, and with a higher segmental airway wall area, compared with COPD patients with no chronic bronchitis.Citation21 In the present study it has, for the first time, clearly been demonstrated that chronic bronchitis is associated with worse HRQL as assessed by EQ-5D and CAT in a well-defined population of COPD patients.

The prevalence of chronic bronchitis in COPD is associated with impaired lung function and increases with disease severity.Citation22 Moreover, several studies have shown that the chronic bronchitis phenotype of COPD is associated with more frequent exacerbationsCitation21 and hospital admissions.Citation23 Mortality risk is also increased in COPD patients with chronic bronchitis compared with the risk in COPD patients with no such symptoms.Citation24 The association of chronic bronchitis with worse HRQL has been shown in patients without COPD using EQ-5D,Citation25 and a similar association between chronic bronchitis and worse HRQL has been shown in COPD patients using the more extensive instruments SGRQCitation22 and SF-12,Citation15,Citation23 but so far this association remains understudied using shorter instruments. Thus, the results from the present study, suggesting that the clinically useful instruments EQ-5D and CAT can identify the association of the chronic bronchitis phenotype with worse HRQL, may be of clinical importance.

An important finding was that musculoskeletal symptoms were significantly associated with worse EQ-5D index. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in COPD influences exercise capacity, fatigue, and activity level,Citation26 and low quadriceps muscle strength is associated with dyspneaCitation27 and mortalityCitation28 in COPD patients. Thus, our finding of an association between musculoskeletal symptoms and worse HRQL could be anticipated, even though it was not previously documented.

The association between osteoporosis and reduced HRQL as assessed by EQ-5D has been well documented in male and female patients from a general population. We have not identified any previous studies showing the specific association of osteoporosis with HRQL in COPD. It is known that the main factor for low HRQL in patients with osteoporosis is osteoporosis-related fractures, of which vertebral fractures seem to have the greatest impact.Citation29 It is also known that the prevalence of vertebral fractures is increased in COPD patients,Citation30 and this may explain the association between osteoporosis and EQ-5D VAS score in our study.

Depression is common in COPD.Citation8 The finding that depression influenced EQ-5D index in our study is consistent with and confirms previous studies, in which depression in COPD was associated with worse HRQL as assessed using EQ-5D,Citation31 SGRQ,Citation32 and Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ).Citation14

Heart disease influences HRQL when estimated by both the generic instrument SF-12 and the disease-specific instrument SGRQ in COPD.Citation12,Citation15 In our study, both generic and disease-specific HRQL instruments were used, but we were not able to identify an association of cardiovascular disease and lower HRQL. Underweight is associated with worse SGRQ score in COPD,Citation13 but no associations with HRQL were found in the present study. As for heart disease, we investigated a population with severe and very severe COPD, where the respiratory disease may outweigh the estimated influence of heart disease and could possibly explain why no associations with heart disease were found. The fact that both SF-36 and SGRQ are more extensive instruments than EQ-5D and CAT may also explain why they are both more suitable for detecting the impact of heart disease. However, the score of another short disease-specific health status instrument, the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ), has been shown to be associated with both heart disease and underweight in COPD patients.Citation14 To our knowledge, the influence of comorbidity and BMI on CAT has not been examined previously, and future comparative studies of CAT and CCQ would therefore be of interest. An additional explanation of the fact that no association was found between cardiovascular disease and HRQL could be that the term “cardiovascular disease” included several conditions such as heart disease, arrhythmia, cerebrovascular disease, and intermittent claudication. It can be speculated that a more specific term such as “heart failure and/or ischemic heart disease” might have been associated with CAT or EQ-5D result.

In addition to the analyses of different comorbid conditions, the findings of the present study suggest that sex (female) is associated with worse HRQL as assessed with EQ-5D index and CAT. This is consistent with previous studies using EQ-5DCitation33 and SGRQ.Citation34 The result of our stratification and interaction analyses is interesting, as it indicates that musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis, and depression are of greater importance in women than in men. A previous study showed that factors influencing HRQL in COPD differ by sex and that the variation in HRQL was more difficult to explain in women.Citation34 Our results might elucidate some differences in how comorbidity influences HRQL in women compared with men. Another explanation of the fact that several associations with HRQL were statistically significant in women but not in men could be limited statistical power in the male group, as the number of women in the study population was higher.

The association of age with worse HRQL as assessed by the EQ-5D index is consistent with some earlier studies that used the EQ-5D VASCitation35 and SF-12.Citation36 The fact that impaired lung function was associated with worse HRQL as measured by all instruments also confirms previous studies in which lung function was associated with EQ-5D,Citation35 CAT,Citation37 SGRQ,Citation35 and SF-12 results.Citation36 The positive association between exacerbation frequency with EQ-5D index and CAT score in our study is also consistent with the findings of several previous studies.Citation12,Citation38

The three pairwise correlations between the evaluated HRQL response variables were statistically significant. Most comorbid conditions were detected by one instrument only, indicating that there is indeed a rationale for using more than one instrument. The benefits of using generic and disease-specific instruments to complement each other have been suggested by other investigators.Citation2 It has been proposed that EQ-5D is suitable for evaluation of chronic conditions and for health utility studies,Citation39 but the ability of the instrument to discriminate between different COPD stagesCitation40,Citation41 and to detect response after pulmonary rehabilitationCitation42 is inferior to that of SGRQ. Because most patients score EQ-5D level 1 or 2, indicating no or only some problems, a “ceiling effect”, where only a few subjects have worse HRQL values, is often demonstrated. This could explain a limited ability to discriminate. Our results support previous suggestions that an improved clinical COPD evaluation strategy would be to assess HRQL using the EQ-5D alongside a disease-specific instrument.Citation43

A strength of this investigation is that it is a multicenter study of patients from almost all the secondary care respiratory units in Sweden with data on several important factors including both a generic and a disease-specific HRQL instrument. The broad definition of present cardiovascular disease, without disease specification, may be a limitation of the study. In previous studies of comorbidities in COPD, “heart disease” has often been used as a comprehensive definitionCitation11,Citation14 and sometimes complemented with ischemic heart disease or heart failure,Citation10,Citation26 which was not the case in the present investigation. It cannot be excluded that the use of a broad definition of cardiovascular disease may have masked an association between cardiovascular disease and HRQL. Another potential limitation is that both pre- and post-bronchodilator values of FEV1 were accepted, which could have resulted in minor misclassifications in COPD stage, but this is expected to have little influence on the HRQL associations. Finally, we would like to emphasize that HRQL is only one dimension of overall disease severity in COPD. The recent GOLD recommendations emphasize that disease severity should include both health status, lung function, and exacerbation frequency, in order to achieve an optimal assessment of severity of disease.Citation1 In addition, several studies have implied that clinical grading by primary care physicians or using a multidimensional instrument such as BODE index, including BMI, obstruction (FEV1% pred), dyspnea (Medical Research Council scale), and exercise capacity measured by 6 minutes walking distance (6MWD), reflect severity of disease better than lung function alone.Citation44,Citation45 However, the aim of our study was to examine the specific associations of comorbidity with HRQL, and not severity of disease.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that in COPD patients treated in secondary care units, several comorbid conditions influence HRQL as measured by EQ-5D and CAT. The results suggest that these two HRQL instruments complement each other. Our study also indicates the novel findings that chronic bronchitis, osteoporosis, and musculoskeletal symptoms are associated with HRQL as reflected by EQ-5D and CAT results. We conclude that the chronic bronchitis phenotype and musculoskeletal symptoms in COPD patients indicate a higher risk of low HRQL. Thus, additional attention should be given to identify these COPD patients and optimize their care.

Acknowledgment

Statistical analyses were performed with help from statistician Gunnar Nordahl, Statistical Support and Solutions Gunnar Nordahl AB.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Associations between explanatory variables and health-related quality of life response variables

Disclosure

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest related to the present study.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease2014 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.orgAccessed October 11, 2014

- EngstromCPPerssonLOLarssonSSullivanMHealth-related quality of life in COPD: why both disease-specific and generic measures should be usedEur Respir J2001181697611510808

- WareJEJrSherbourneCDThe MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selectionMed Care19923064734831593914

- GandekBWareJEAaronsonNKCross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life AssessmentJ Clin Epidemiol19985111117111789817135

- EuroQol GroupEuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of lifeHealth Policy199016319920810109801

- JonesPWQuirkFHBaveystockCMLittlejohnsPA self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St George’s Respiratory QuestionnaireAm Rev Respir Dis19921456132113271595997

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- CazzolaMBettoncelliGSessaECricelliCBiscioneGPrevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration201080211211920134148

- Antonelli IncalziRFusoLDe RosaMCo-morbidity contributes to predict mortality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J19971012279428009493663

- AlmagroPCabreraFJDiezJWorking Group on COPD, Spanish Society of Internal MedicineComorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD: the EPOC en Servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) studyChest201214251126113323303399

- WijnhovenHAKriegsmanDMHesselinkAEde HaanMSchellevisFGThe influence of co-morbidity on health-related quality of life in asthma and COPD patientsRespir Med200397546847512735662

- BurgelPREscamillaRPerezTINITIATIVES BPCO Scientific CommitteeImpact of comorbidities on COPD-specific health-related quality of lifeRespir Med2013107223324123098687

- KatsuraHYamadaKKidaKBoth generic and disease specific health-related quality of life are deteriorated in patients with underweight COPDRespir Med200599562463015823461

- SundhJStallbergBLisspersKMontgomerySMJansonCCo-morbidity, body mass index and quality of life in COPD using the Clinical COPD QuestionnaireCOPD20118317318121513436

- JansonCMarksGBuistSThe impact of COPD on health status: findings from the BOLD studyEur Respir J20134261472148323722617

- KruisALStällbergBJonesRCPrimary care COPD patients compared with large pharmaceutically-sponsored COPD studies: an UNLOCK validation studyPLoS One201493e9014524598945

- DolanPModeling valuations for EuroQol health statesMed Care19973511109511089366889

- LandboCPrescottELangePVestboJAlmdalTPPrognostic value of nutritional status in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med199916061856186110588597

- HanMKAgustiACalverleyPMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPDAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182559860420522794

- Izquierdo-AlonsoJLRodriguez-GonzálezmoroJMde Lucas-RamosPPrevalence and characteristics of three clinical phenotypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Respir Med2013107572473123419828

- KimVHanMKVanceGBCOPDGene InvestigatorsThe chronic bronchitic phenotype of COPD: an analysis of the COPDGene StudyChest2011140362663321474571

- AgustiACalverleyPMCelliBEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigatorsCharacterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Res20101112220831787

- de OcaMMHalbertRJLopezMVThe chronic bronchitis phenotype in subjects with and without COPD: the PLATINO studyEur Respir J2012401283622282547

- Ekberg-AronssonMPehrssonKNilssonJANilssonPMLofdahlCGMortality in GOLD stages of COPD and its dependence on symptoms of chronic bronchitisRespir Res200569816120227

- HungerMThorandBSchunkMMultimorbidity and health-related quality of life in the older population: results from the German KORA-age studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes201195321767362

- PatelARHurstJRExtrapulmonary comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: state of the artExpert Rev Respir Med20115564766221955235

- SeymourJMSpruitMAHopkinsonNSThe prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD and the relationship with disease severityEur Respir J2010361818819897554

- SwallowEBReyesDHopkinsonNSQuadriceps strength predicts mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax200762211512017090575

- RouxCWymanAHoovenFHGLOW InvestigatorsBurden of non-hip, non-vertebral fractures on quality of life in postmenopausal women: the Global Longitudinal study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW)Osteoporos Int201223122863287122398855

- PapaioannouAParkinsonWFerkoNPrevalence of vertebral fractures among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in CanadaOsteoporos Int2003141191391714551675

- ClelandJALeeAJHallSAssociations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patientsFam Pract200724321722317504776

- NgTPNitiMTanWCCaoZOngKCEngPDepressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of lifeArch Intern Med20071671606717210879

- NaberanKAzpeitiaACantoniJMiravitllesMImpairment of quality of life in women with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med2012106336737322018505

- de TorresJPCasanovaCHernándezCGender associated differences in determinants of quality of life in patients with COPD: a case series studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes200647217007639

- StåhlELindbergAJanssonSAHealth-related quality of life is related to COPD disease severityHealth Qual Life Outcomes200535616153294

- MartinARodriguez-Gonzalez MoroJMIzquierdoJLGobarttEde LucasPHealth-related quality of life in outpatients with COPD in daily practice: the VICE Spanish StudyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083468369219283915

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWProperties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European studyEur Respir J2011381293521565915

- AgustíASolerJJMolinaJIs the CAT questionnaire sensitive to changes in health status in patients with severe COPD exacerbations?COPD20129549249822958111

- HeyworthITHazellMLLinehanMFFrankTLHow do common chronic conditions affect health-related quality of life?Br J Gen Pract200959568e353e35819656444

- MennPWeberNHolleRHealth-related quality of life in patients with severe COPD hospitalized for exacerbations – comparing EQ-5D, SF-12 and SGRQHealth Qual Life Outcomes201083920398326

- PickardASYangYLeeTAComparison of health-related quality of life measures in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth Qual Life Outcomes201192621501522

- RingbaekTBrondumEMartinezGLangePEuroQoL in assessment of the effect of pulmonary rehabilitation COPD patientsRespir Med2008102111563156718693003

- WilkeSJanssenDJWoutersEFScholsJMFranssenFMSpruitMACorrelations between disease-specific and generic health status questionnaires in patients with advanced COPD: a one-year observational studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes2012109822909154

- Medinas AmorosMMas-TousCRenom-SotorraFRubi-PonsetiMCenteno-FloresMJGorriz-DolzMTHealth-related quality of life is associated with COPD severity: a comparison between the GOLD staging and the BODE indexChron Respir Dis200962758019411567

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWPatient-centred assessment of COPD in primary care: experience from a cross-sectional study of health-related quality of life in EuropePrim Care Respir J201221332933622885563