Abstract

COPD is associated with different comorbid diseases, and their frequency increases with age. Comorbidities severely impact costs of health care, intensity of symptoms, quality of life and, most importantly, may contribute to life span shortening. Some comorbidities are well acknowledged and established in doctors’ awareness. However, both everyday practice and literature searches provide evidence of other, less recognized diseases, which are frequently associated with COPD. We call them underrecognized comorbidities, and the reason why this is so may be related to their relatively low clinical significance, inefficient literature data, or data ambiguity. In this review, we describe rhinosinusitis, skin abnormalities, eye diseases, different endocrinological disorders, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Possible links to COPD pathogenesis have been discussed, if the data were available.

Introduction

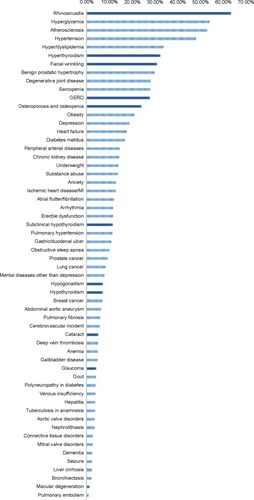

COPD is a complex, multicomponent disease associated with pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations.Citation1,Citation2 More than 30% of patients have one additional chronic disease, and another 40% have two or more comorbidities.Citation2,Citation3 Comorbid diseases prolong hospitalization and are risk factors of short- and long-term unfavorable prognoses.Citation4 They are undeniably related to increased health care costsCitation5,Citation6 and decreased quality of life.Citation3,Citation7 Depression, anxiety, peripheral artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and symptomatic heart failure have been defined as those concurrent conditions that most severely impact patients health status.Citation8 Some COPD-associated diseases are well recognized and are listed in official documents on COPD, such as the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). They include: cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) (ischemic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, hypertension); osteoporosis (frequently associated with weight loss and sarcopenia); anxiety and depression; lung cancer; infections; metabolic syndrome and diabetes; bronchiectasis; and impaired cognitive function.Citation9 and shows the prevalence of different chronic conditions, including underrecognized comorbidities discussed in this paper in patients suffering from COPD, on the basis of the available literature.

Figure 1 The prevalence of comorbidities in COPD (prevalence >2%).

Notes: The diseases that are the topic of this study are marked in dark blue. Prevalence was calculated as a weighted average based on the study’s sample size. When the data in a manuscript were unclear, the researchers contacted the corresponding author of the manuscript.Citation8,Citation18,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33,Citation39,Citation52,Citation62,Citation82,Citation83,Citation86,Citation89–Citation91,Citation95–Citation104 The calculations were performed and the graph was made in Microsoft Excel 2013.

Abbreviations: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

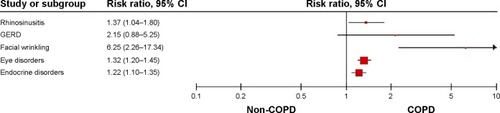

Figure 2 Graph presents the risk ratio with the 95% CI of comorbidities, or groups of comorbidities, that constitute the topic of this study, as based on multiple studies.Citation39,Citation68,Citation91

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The links between COPD and other concomitant diseases are still a subject of debate. In some cases, COPD complications (like hypoxemia/hypercapnia or pulmonary hypertension) may be responsible for certain extrapulmonary symptoms. Comorbidities, like the mere index disease, may represent accelerated aging processes with shared pathological mechanisms, when chronic systemic inflammation and oxidative stress result in telomere dysfunction and DNA damage.Citation10–Citation13 Inflammatory local response to inhaled particles and gases (mostly tobacco smoking) may spread out of the respiratory tract (the “spill-over” theory) or, alternatively, one common trigger (like cigarette smoking) induces systemic inflammation first, and different organ manifestations result from this common root.Citation2,Citation10 In COPD, systemic inflammation with chronic low-grade elevation of circulating proinflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and interleukin (IL)-6 is associated with emphysema,Citation14 accelerated disease progression characterized by acute exacerbations, COPD-related hospitalization, and rapid decline of force expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).Citation15–Citation17 The same markers of systemic inflammation are also associated with aging and comorbid diseases, such as CVD, obesity, and diabetes, and are believed to actively participate in the pathogenesis of these conditions.Citation18–Citation20 Of note, according to some studies, not all COPD patients present increased levels of inflammatory mediators in the blood. Garcia-Aymerich et alCitation20 identified a “systemic COPD” subtype characterized by increased levels of inflammatory mediators in the blood only in a subgroup of less than one-third of the cohort. These patients were also at greater risk of having obesity, CVD, and diabetes.Citation20 Therefore, other mechanisms may be also involved in the pathogenesis of COPD and its comorbidities.

According to García-Olmos et alCitation21 COPD most frequently clusters with obesity, osteoporosis, deafness and hearing loss, malignant neoplasms, degenerative joint disease, benign prostatic hypertrophy, generalized atherosclerosis, glaucoma, chronic liver disease, dementia and delusions, chronic skin ulcer, cardiac valve disease, and Parkinson’s disease. It is worth noting that some of these diseases are not always recognized by medical professionals as frequent COPD comorbidities.

Several publications, as well as everyday clinical observations, also suggest the frequent coexistence of other conditions and manifestations, as well as involvement of organs other than those defined by GOLD.Citation9 These conditions may not be fully recognized either due to their relatively low clinical significance, inefficient literature data, or data ambiguity. Therefore, the aim of this review is to describe and discuss underrecognized extrapulmonary COPD manifestations. The term underrecognized is used in this paper to define diseases that are not listed in the updated edition of GOLD, but for which publications showing such coexistence exist. The list of exclusion and inclusion criteria is provided in . The diseases that comprise the aforementioned criteria are symptoms from the upper respiratory tract (rhinosinusitis), skin changes and accelerated aging of the skin, eye diseases, endocrine disorders (other than obesity and diabetes), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The aim of this review is to discuss the clinical and epidemiological data on the coexistence of these diseases with COPD, as well as to provide (when possible) an explanation of such frequent coexistence.

Table 1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria for underrecognized COPD comorbidities

Search methodology

The initial search was conducted using PubMed with the subject headings “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease” (or “COPD”) and “comorbidities” (or “comorbidity” or “comorbidities”). Detailed headings in the area of: rhinosinusitis; skin abnormalities; eye diseases; endocrinological disorders; and gastroesophageal disease (GERD) were used. The comorbidities were selected on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria, as shown in . Only English articles with available abstracts were retrieved. For relevant titles, the abstracts were reviewed and, if still relevant, the full version of the article was obtained. References within the selected articles were also reviewed for their relevance. shows the number of hits and final selection for each thematic area. The most relevant papers for this selection (showing frequent coexistence of these diseases with COPD), along with the strength of the patients cohorts, are provided in .

Table 2 The process of the PubMed search in selected areas

Table 3 List of the most relevant papers per condition

Rhinosinusitis in COPD

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) may be defined according to the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps (EP3OS) by presentation of symptoms and either endoscopic evidence of polyps or radiological evidence by computed tomography (CT).Citation22 These criteria may be difficult to fulfill in population-based studies. That is why in the majority of such studies, the definition of CRS is based on the sole symptoms and/or the patient’s reported physician-made diagnosis. The symptom-based diagnosis may be biased by several factors, leading to CRS overdiagnosis;Citation23 however, in the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GACitation2 LEN) study,Citation24 in which 57,128 responders from 12 countries were recruited, the value of a postal questionnaire was verified against nasal endoscopy in a subgroup of over 300 patients, and symptom-based diagnosis was proved reliable. In this large study, the overall prevalence of CRS in Europe was estimated as 10.9%, and it was more common in smokers (odds ratio [OR] =1.7). The age group found to be at the highest risk of having CRS was 55–64 years.Citation25 CRS (both with and without nasal polyps) is more frequent in asthma (18%), atopic dermatitis (7%), inflammatory bowel disease (3.5%), autoimmune disorders (up to 5.9%), and the frequency of CRS associated with polyps was higher in the first three instances.Citation26

The term “common airway disease” is used to describe the frequent coexistence of asthma and upper airway diseases – most frequently, allergic and nonallergic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. It has been estimated that approximately 90% of patients suffering from allergic asthma present with signs and symptoms of rhinitis, and about one-third of patients with rhinitis may have asthma.Citation27 This well-recognized association led to the formation of theories on the common pathogenesis of these concomitant diseases.Citation28

Several authors reported on the higher incidence of CRS in COPD patients.Citation29–Citation33 The figures depend mostly on the definition of CRS applied in a study. Upper airway symptom frequency among COPD patients may be as high as 88%,Citation33 but when more objective tests were applied for CRS diagnosis (like CT scans), lower numbers were reported (53%).Citation31 Smoking should be considered the most important risk factor of CRS. Young smokers with normal lung function present with signs of upper airway inflammation, like increased nasal lavage cell number (the cellular pattern composed mainly of macrophages, ciliated, and goblet cells) and increased concentration of myeloperoxidase, suggestive of neutrophil recruitment and activation.Citation34 Smoking habit decreases the quality of life related to rhinosinusitis symptoms.Citation35 Smokers without evidence of pulmonary pathology also have more pathological changes in their sinus CT scans.Citation36 Many in vitro studies confirm the deleterious effect of cigarette smoke (CS) on nasal epithelial cells.Citation37,Citation38 Despite these experimental studies, in vivo data on the role of smoking in COPD-associated rhinosinusitis are scarce. Only COPD smokers (but not the entire COPD group) were shown to have reduced mucociliary clearance and increased concentration of 8-isoprostane (a marker of oxidative stress) in nasal lavage when compared to healthy nonsmoking controls. However, no relation to smoking history and current smoking status were found for the severity of symptoms and intensity of mucosal changes.Citation39

CRS symptoms significantly impair COPD patients’ quality of life, which is usually assessed by dedicated questionnaires (Sino–Nasal Outcome Test [SNOT]-20, SNOT-22, or Sino–Nasal Assessment Questionnaire [SNAQ]-11).Citation31–Citation33,Citation39 However CRS symptoms do not impact the disease-specific quality of life, as scored by the use of St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, suggesting that symptoms from the lower and upper respiratory tract influence the quality of life in an independent manner.Citation31,Citation39 The most frequently reported symptom is rhinorrhea.Citation31 Mucosal abnormalities were reported in endoscopyCitation31,Citation39 and CT.Citation33 The symptoms were more intensive, and CT changes were more frequent in patients with more severe obstruction (grade III and IV),Citation33 but this regularity was not confirmed by other authors.Citation39 In concordance with the “common airway” concept, the most important would be to show the identity of inflammation in the lower and upper airways. Piotrowska et alCitation39 have not found any differences in the number or percentage of neutrophils, nor differences in the concentration of LTB4 – an eicosanoid related to neutrophilic inflammation – in nasal lavages between COPD and controls. This is contrary to other authors, who found neutrophilic response in the nasal mucosa of stable COPD patients. Hurst et alCitation40 found elevated IL-8 concentrations in the nasal lavage of COPD patients, and a positive correlation with sputum IL-8. Interestingly, Hens et alCitation32 reported elevated concentrations of eotaxin (an eosinophilic marker), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and interferon-γ in the nasal lavage of COPD patients; moreover, the very same cytokines were found to be elevated in lavages of patients with asthma. Vachier et alCitation41 reported higher numbers of CD8+ and neutrophils in the nasal biopsies of COPD patients. This is the only study so far, with the use of nasal biopsy, to prove the typical signs of COPD inflammation in the nose. No relation to systemic inflammation, defined as elevated serum C-reactive protein concentration, was found.Citation39,Citation40

Skin in COPD

A typical “smokers’ face” is characterized by prominent wrinkles, gauntness of facial features, gray appearance of the skin, and a swollen complexion. The association between smoking habit, its intensity, and skin wrinkling was documented many years ago.Citation42 Skin wrinkling supposedly reflects accelerated skin aging. CS induces low-grade skin inflammation mediated by reactive oxygen species, which leads to alterations in extracellular matrix turnover. Collagen I and collagen III content in smokers’ skin is decreased, which may result from decreased collagen biosynthesis and/or increased degradation. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases ([MMP]-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, and MMP-8) and decreased expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 have been reported.Citation43–Citation47 The skin inflammation induced by smoking may resemble that related to chronic exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation – also referred to as photodamage or photoaging. This type of damage is associated with skin infiltration with mast cells, macrophages, CD4+CD45RO+ T-cells, and CD1a+ dendritic cells.Citation48–Citation50 It was shown, that smoking accelerates skin photoaging, whereas smoking cessation may slow down this process.Citation51

The skin of COPD patients also shows signs of accelerated aging, but only in those parts related to the smoking habit. Patel et alCitation52 were the first to prove the susceptibility of smokers with facial wrinkling to COPD. According to these authors, facial wrinkling was not only related to COPD risk (OR =5.0), but its intensity also correlated with the extent of emphysema on CT scans. Other authors have shown that COPD patients have increased skin elastin degradation when compared to smoking-matched control subjects. It was more pronounced in the areas exposed to solar radiation when compared to areas protected from the sun. Of much interest, the intensity of elastin degradation in skin biopsies was correlated with emphysema severity, as assessed by chest CT, and it was shown to be related to messenger RNA expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9.Citation53 This finding is aligned with the results of another group of authors, who found an association between elastin fiber abnormalities in the reticular dermis and lung function impairment of an obstructive pattern.Citation54 However, skin fibroblasts do not show the same “senescent” as the emphysema-derived pulmonary fibroblast phenotype.Citation55

Advanced glycation end products (AGE) are generated by the glycation and oxidation of proteins. AGE accumulate in the tissues and thus may impair the function of different organs. Moreover, when attached to cellular receptors (RAGE), they induce a cascade of events leading to the activation of nuclear factor kappa B, which result in the generation of proinflammatory cytokines. AGE and RAGE have been associated with the pathogenesis of many diseases with underlying systemic inflammation, such as diabetes, heart insufficiency, chronic kidney disease and, recently, COPD.Citation56–Citation58 Serum AGE and cellular RAGE expression were both elevated in COPD,Citation59 and sRAGE, a circulating soluble decoy receptor, was shown to be decreased in COPD, which was inversely correlated with the degree of emphysema.Citation60 The skin of COPD patients accumulate AGE, which can be detected by skin autofluorescence.Citation61,Citation62 In none of these studies does skin autofluorescence intensity correlate with COPD severity.

Eyes in COPD

Hypoxia and vascular mediators may be involved in the etiology of some eye disorders. A constant supply of oxygen is crucial to maintain adequate organ function – in particular, in tissues with high energy demand, such as the retina. Thus, it does not come as a surprise that even small alterations in retinal oxygen tension may lead to tissue hypoxia and neuronal death.Citation63 New instruments allow for the noninvasive measurement of retinal oxygen saturation in humans.Citation63 Celik et alCitation64 evaluated the hemodynamic changes in the extraocular orbital vessels of COPD using color Doppler ultrasonography and showed that severe (stage 3) COPD is associated with impaired retrobulbar hemodynamics.

Glaucoma and cataract may be assigned to side effects of COPD treatment. Topical and systemic corticosteroids are well known to raise intraocular pressure, while the effect of inhaled corticosteroids on the risk of glaucoma remains uncertain. In a large cohort of elderly patients treated for airways disease, neither current nor continuous use of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids resulted in an increased risk of glaucoma or raised intraocular pressure requiring treatment.Citation65 COPD, like glaucoma and cataract, is a common disease in the elderly. In those individuals above the age of 70 years, glaucoma prevalence is close to 4%.Citation66 A population-based cohort study with nested case–control analysis using the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database did not find an association between glaucoma and obstructive airway diseases.Citation67 Quite the contrary, Soriano et alCitation68 in a large cohort of COPD patients (number [n] =2,699) from the same database, found that COPD compared to non-COPD patients are at higher risk of glaucoma within the first year after COPD diagnosis (risk ratio [RR] =1.3). Of note, 2% of COPD patients had a record of their cataracts, but this rate was not different than that of the non-COPD cohort.Citation68

It was also shown that individuals with neovascular age-related macular degeneration are significantly more likely to have emphysema and COPD. Also, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, atherosclerosis, arthritis, coronary heart disease, cataract, glaucoma, and myopia were found to be more frequent in these patients.Citation69 Independently of smoking, a history of emphysema, respiratory symptoms, and lung function impairment are modestly, but inconsistently, associated with the incidence and progression of age-related macular degeneration.Citation70

Significant decreases in endothelial cell density, hexagonality, corneal thickness, and a significant increase in the endothelial cell size coefficient of variation were found in COPD patients. They also presented with a significant decrease in serum antioxidant enzyme paraoxonase (PON)1 activity, but not in PON1 concentration. Serum PON1 activity showed a significant direct association with endothelial cell density and an inverse association with corneal thickness. Therefore, the authors suggest that PON1 may be involved in the pathophysiology of corneal endothelial alterations in patients with COPD.Citation71

Endocrinological disorders in COPD patients

Diabetes mellitus type 2, osteoporosis, and metabolic syndrome are well-known endocrinological comorbidities in COPD.Citation9 In some patients, COPD is associated with muscle wasting and weakness, and thus many reports are focused on anabolic hormones, thyroid function, and the adrenal glands.Citation72 A range of mechanisms, including systemic inflammation, neurohormones, blood gas disturbances, and glucocorticoid administration, contribute to the anabolic/catabolic imbalance and impaired whole-body metabolism in COPD.Citation73–Citation76

Some studies show that thyroid diseases are more frequent among patients with COPD. In a big population-based study performed in the city of Madrid, Spain, it was shown that the prevalence of a thyroid disease was higher in COPD patients (14.21%) than the expected standardized prevalence of chronic diseases (11.06%).Citation21 A strong positive correlation between the total T3/total T4 ratio and PaO2 in patients with respiratory insufficiency was described.Citation75 Increased free (F)T3 concentrations have been reported in stable COPD, with a positive association to PaCO2,Citation76 while others reported lower total T3, FT3, and totalT3/totalT4 ratios in patients with severe hypoxemia.Citation77 Mancini et alCitation78 evaluated thyroid hormones and antioxidant defense – the lipophilic coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) and total antioxidant capacity–in COPD patients to reveal the presence of a low-T3 syndrome in COPD and to investigate the correlation between thyroid hormones, lung function parameters, and antioxidants. They found significantly lower FT3 and FT4 levels and significantly higher thyroid-stimulating hormone levels in COPD patients versus controls.Citation78 Their research seems to indicate an increased oxidative stress in low FT3 COPD and a role of FT3 in modulating antioxidant defense. These data might suggest the need for thyroid replacement therapy in a low-T3 syndrome in COPD patients.Citation78

Many studies have shown that middle-aged and elderly COPD patients may develop hypogonadism.Citation79–Citation82 The prevalence of hypogonadism in men with COPD can range from 22%–69%, and it has been associated with several other systemic manifestations including osteoporosis, depression, and muscle weakness.Citation79 However, the relationship between hypogonadism and COPD still remains poorly understood. The current literature is, at best, circumstantial.Citation79,Citation82 A sex hormone deficiency in men can be correlated with COPD stages and disease progression.Citation83 There are only a few long-term trials evaluating the effects of androgens on the parameters of respiratory function in patients with COPD.Citation79,Citation83,Citation84 Changes of testosterone levels in patients with COPD correlate with FEV1, hypoxemia, and hypercapnia levels.Citation79,Citation84 Glucocorticosteroids exacerbate androgen deficiency in patients with COPD, and the use of hormone replacement therapy with testosterone in these patients is justified. Androgens, especially the testosterone depot, can be effectively used in the treatment and rehabilitation of patients with COPD.Citation85 Testosterone replacement therapy may result in modest improvements in fat-free mass and limb muscle strength, but its therapeutic efficacy in COPD patients still remains controversial.Citation79

Adrenal insufficiency (AI) is an uncommon but life-threatening disorder if it progresses to adrenal crisis. In some COPD patients, previous glucocorticosteroid intake may be responsible for the occurrence of AI. The annual incidence of AI in Taiwan has continuously increased in recent years, and elderly patients accounted for the majority of the increase. The most common comorbidity for AI was pneumonia (6.4%), followed by urinary tract infection (6.4%), diabetes mellitus (6.2%), electrolyte imbalance (4.8%), and COPD (4.5%).Citation85

It has been suggested that COPD patients have abnormal circadian rhythms, and they suffer from cognitive function, mood/anxiety, and sleep abnormalities because of disturbances in corticosterone release – an adrenal steroid that plays a considerable role in stress and anti-inflammatory responses.Citation74

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

The frequent coexistence of GERD among patients with COPD has been described before.Citation86 Treatment with bronchodilators (such as theophylline or beta-agonists) has been considered as causative factors; however, the literature data on the possible causative links are ambiguous.Citation87 Obstructive sleep apnea, a frequent comorbidity of COPD, may also exacerbate diaphragm and lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction and increase the propensity for and severity of GERD.Citation88 It may not be excluded that mere COPD symptoms (like frequent and severe cough) increase the intrathoracic pressure, thus contributing to reflux occurrence; however, the data confirming this hypothesis are lacking. GERD was present in almost one-third of elderly COPD patients and it shows female predominance.Citation89 It was shown to be associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular comorbidity.Citation90 It significantly impacts the severity of symptomsCitation89,Citation90 and quality of life.Citation89,Citation90 Coexistent GERD significantly increases health care costs.Citation90 GERD symptoms were also shown to be associated with a higher risk of exacerbations (RR =6.5).Citation91 The presence of GERD symptoms does not influence the inflammatory response in the airways;Citation92 therefore, other mechanisms by which GERD affects COPD exacerbations should be sought. The increase in bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with GERD could explain the impact on COPD symptoms and the increased risk of exacerbations; however, it was shown that the treatment of patients with severe hyperresponsiveness (both asthma and COPD) and coexisting GERD with a high-dose proton pump inhibitor for a period of 3 months did not alleviate respiratory symptoms, nor did it decrease the threshold of bronchial hyperreactivity.Citation92

Other underrecognized manifestations

Little was known about the relationships between COPD and liver diseases until population-based surveys demonstrated that COPD patients have a substantially elevated risk of gallbladder disease, pancreatic disease, and asymptomatic elevations of hepatic transaminases unrelated to right heart failure.Citation93 The same survey and retrospective study revealed that renal complications of COPD are common, especially among patients with hypoxemia and hypercarbia. Renal–endocrine mechanisms, tissue hypoxia, and vascular rigidity play roles in the pathophysiology, but a causal relationship is not precisely recognized.Citation93

Conclusion

Not all is known about COPD comorbidities. Many symptoms may be overlooked or belittled by physicians. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between COPD complications, drug-related symptoms and treatment complications, and real comorbidities. Quality of life is one of the main indications of well-being and it may be severely impaired by still underrecognized manifestations. Some of these comorbidities may even be life threatening. Common pathways may be involved in the pathogenesis of COPD and its comorbidities. Therefore, better recognition of these complicated relationships between different diseases may be important for the knowledge on the COPD itself. Improved management of these conditions may result in improved quality of life and health care-related cost reduction.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by the Healthy Ageing Research Centre project (REGPOT-2012-2013-1, 7FP).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AgustiASobradilloPCelliBAddressing the complexity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: from phenotypes and biomarkers to scale-free networks, systems biology, and P4 medicineAm J Respir Crit Care Med201118391129113721169466

- BarnesPJCelliBRSystemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20093351165118519407051

- BorosPWLubińskiWHealth state and the quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Poland: a study using the Euro-QoL-5D questionnairePol Arch Med Wewn20121223738122354456

- Antonelli IncalziRFusoLDe RosaMCo-morbidity contributes to predict mortality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J19971012279428009493663

- GlynnLGValderasJMHealyPThe prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and costFam Pract201128551652321436204

- BustacchiniSChiattiCFurneriGLattanzioFMantovaniLGThe economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderly: results from a systematic review of the literatureCurr Opin Pulm Med201117Suppl 1S35S4122209929

- McDaidOHanlyMJRichardsonKKeeFKennyRASavvaGMThe effect of multiple chronic conditions on self-rated health, disability and quality of life among the older populations of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland: a comparison of two nationally representative cross-sectional surveysBMJ Open201336e002571

- FreiAMuggensturmPPutchaNFive comorbidities reflected the health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the newly developed COMCOLD indexJ Clin Epidemiol201467890491124786594

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [homepage on the Internet]Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPDGlobal Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)2015Leuven (Belgium), Marburg (Germany) Available from: http://web.archive.org/web/20150227051533/http://www.goldcopd.orgAccessed February 27, 2015

- ItoKBarnesPJCOPD as a disease of accelerated lung agingChest2009135117318019136405

- AmsellemVGary-BoboGMarcosETelomere dysfunction causes sustained inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011184121358136621885626

- ItoKColleyTMercadoNGeroprotectors as a novel therapeutic strategy for COPD, an accelerating aging diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012764165223055713

- BarnesPJMechanisms of development of multimorbidity in the elderlyEur Respir J201545379080625614163

- PapaioannouAIMaziotiAKiropoulosTSystemic and airway inflammation and the presence of emphysema in patients with COPDRespir Med2010104227528219854037

- SalanitroAHRitchieCSHovaterMInflammatory biomarkers as predictors of hospitalization and death in community-dwelling older adultsArch Gerontol Geriatr2012543e387e39122305611

- MoyMLTeylanMDanilackVAGagnonDRGarshickEAn index of daily step count and systemic inflammation predicts clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Am Thorac Soc201411214915724308588

- ManninoDMValviDMullerovaHTal-SingerRFibrinogen, COPD and mortality in a nationally representative U.S. cohortCOPD20129435936622489912

- VanfleterenLESpruitMAGroenenMClusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187772873523392440

- FuJJMcDonaldVMGibsonPGSimpsonJLSystemic inflammation in older adults with asthma-COPD overlap syndromeAllergy Asthma Immunol Res20146431632424991455

- Garcia-AymerichJGómezFPBenetMPAC-COPD Study GroupIdentification and prospective validation of clinically relevant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) subtypesThorax201166543043721177668

- García-OlmosLSalvadorCHAlberquillaÁComorbidity patterns in patients with chronic diseases in general practicePLoS One201272e3214122359665

- FokkensWJLundVJMullolJEPOS 2012: European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. A summary for otorhinolaryngologistsRhinology201250111222469599

- HalawiAMSmithSSChandraRKChronic rhinosinusitis: epidemiology and costAllergy Asthma Proc201334432833423883597

- TomassenPNewsonRBHoffmansRReliability of EP3OS symptom criteria and nasal endoscopy in the assessment of chronic rhinosinusitis – a GA2 LEN studyAllergy201166455656121083566

- HastanDFokkensWJBachertCChronic rhinosinusitis in Europe – an underestimated disease. A GA2 LEN studyAllergy20116691216122321605125

- ChandraRKLinDTanBChronic rhinosinusitis in the setting of other chronic inflammatory diseasesAm J Otolaryngol201132538839120832903

- LeynaertBNeukirchFDemolyPBousquetJEpidemiologic evidence for asthma and rhinitis comorbidityJ Allergy Clin Immunol20001065 SupplS201S20511080732

- NutkuETodaMHamidQARhinitis, nasal polyposis and asthma: pathological aspectsWallaertBChanezPGodardPThe Nose and Lung Diseases. European Respiratory Monograph20016115142

- ChenYDalesRLinMThe epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in CanadiansLaryngoscope200311371199120512838019

- RobertsNJLloyd-OwenSJRapadoFRelationship between chronic nasal and respiratory symptoms in patients with COPDRespir Med200397890991412924517

- HurstJRWilkinsonTMDonaldsonGCWedzichaJAUpper airway symptoms and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Respir Med200498876777015303642

- HensGVanaudenaerdeBMBullensDMSinonasal pathology in nonallergic asthma and COPD: ‘united airway disease’ beyond the scope of allergyAllergy200863326126718053011

- KelemenceAAbadogluOGumusCBerkSEpozturkKAkkurtIThe frequency of chronic rhinosinusitis/nasal polyp in COPD and its effect on the severity of COPDCOPD20118181221299473

- NicolaMLCarvalhoHBYoshidaCTYoung “healthy” smokers have functional and inflammatory changes in the nasal and the lower airwaysChest20141455998100524307008

- LachanasVATseaMTsiouvakaSExarchosSTSkoulakisCEBizakisJGThe effect of active cigarette smoking on Sino-Nasal Outcome Test in 127 subjects without rhinologic disease. A prospective studyClin Otolaryngol2015401565925314243

- UhliarovaBAdamkovMSvecMCalkovskaAThe effect of smoking on CT score, bacterial colonization and distribution of inflammatory cells in the upper airways of patients with chronic rhinosinusitisInhal Toxicol201426741942524862976

- PaceEFerraroMDi VincenzoSOxidative stress and innate immunity responses in cigarette smoke stimulated nasal epithelial cellsToxicol In Vitro201428229229924269501

- VirginFWAzbellCSchusterDExposure to cigarette smoke condensate reduces calcium activated chloride channel transport in primary sinonasal epithelial culturesLaryngoscope201012071465146920564721

- PiotrowskaVMPiotrowskiWJKurmanowskaZMarczakJGórskiPAntczakARhinosinusitis in COPD: symptoms, mucosal changes, nasal lavage cells and eicosanoidsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2010510711720631813

- HurstJRWilkinsonTMPereraWRDonaldsonGCWedzichaJARelationships among bacteria, upper airway, lower airway, and systemic inflammation in COPDChest200512741219122615821198

- VachierIVignolaAMChiapparaGInflammatory features of nasal mucosa in smokers with and without COPDThorax200459430330715047949

- DaniellHWSmoker’s wrinkles. A study in the epidemiology of “crow’s feet”Ann Intern Med19717568738805134897

- YinLMoritaATsujiTAlterations of extracellular matrix induced by tobacco smoke extractArch Dermatol Res2000292418819410836612

- LahmannCBergemannJHarrisonGYoungARMatrix metalloproteinase-1 and skin ageing in smokersLancet2001357926093593611289356

- KnuutinenAKokkonenNRisteliJSmoking affects collagen synthesis and extracellular matrix turnover in human skinBr J Dermatol2002146458859411966688

- JustMRiberaMMonsóELorenzoJCFerrándizCEffect of smoking on skin elastic fibres: morphometric and immunohistochemical analysisBr J Dermatol20071561859117199572

- OrtizAGrandoSASmoking and the skinInt J Dermatol201251325026222348557

- BossetSBonnet-DuquennoyMBarréPPhotoageing shows histological features of chronic skin inflammation without clinical and molecular abnormalitiesBr J Dermatol2003149482683514616376

- IddamalgodaALeQTItoKTanakaKKojimaHKidoHMast cell tryptase and photoaging: possible involvement in the degradation of extra cellular matrix and basement membrane proteinsArch Dermatol Res2008300Suppl 1S69S7617968569

- KaukinenAFitzgibbonAOikarinenAHinkkanenLViinikanojaMHarvimaITIncreased numbers of tryptase-positive mast cells in the healthy and sun-protected skin of tobacco smokersDermatology2014229435335825376107

- ChungJHLeeSHYounCSCutaneous photodamage in Koreans: influence of sex, sun exposure, smoking, and skin colorArch Dermatol200113781043105111493097

- PatelBDLooWJTaskerADSmoking related COPD and facial wrinkling: is there a common susceptibility?Thorax200661756857116774949

- MaclayJDMcAllisterDARabinovichRSystemic elastin degradation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax201267760661222374923

- JustMMonsóERiberaMLorenzoJCMoreraJFerrandizCRelationships between lung function, smoking and morphology of dermal elastic fibresExp Dermatol2005141074475116176282

- MüllerKCPaaschKFeindtBIn contrast to lung fibroblasts – no signs of senescence in skin fibroblasts of patients with emphysemaExp Gerontol200843762362818295997

- BuckleySTEhrhardtCThe receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and the lungJ Biomed Biotechnol2010201091710820145712

- LeeEJParkJHReceptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE), its ligands, and soluble RAGE: potential biomarkers for diagnosis and therapeutic targets for human renal diseasesGenomics Inform201311422422924465234

- MorbiniPVillaCCampoIZorzettoMInghilleriSLuisettiMThe receptor for advanced glycation end products and its ligands: a new inflammatory pathway in lung disease?Mod Pathol200619111437144516941014

- WuLMaLNicholsonLFBlackPNAdvanced glycation end products and its receptor (RAGE) are increased in patients with COPDRespir Med2011105332933621112201

- SmithDJYerkovichSTTowersMACarrollMLThomasRUphamJWReduced soluble receptor for advanced glycation end-products in COPDEur Respir J201137351652220595148

- GopalPReynaertNLScheijenJLPlasma advanced glycation end-products and skin autofluorescence are increased in COPDEur Respir J201443243043823645408

- HoonhorstSJLo Tam LoiATHartmanJEAdvanced glycation end products in the skin are enhanced in COPDMetabolism20146391149115625034386

- PalkovitsSLastaMToldRRetinal oxygen metabolism during normoxia and hyperoxia in healthy subjectsInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20145584707471325015353

- CelikCTokgözOSerifoğluLTorMAlpayAErdemZColor Doppler evaluation of the retrobulbar hemodynamic changes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: COPD and retrobulbar hemodynamic changesUltrason Imaging201436317718624894868

- GonzalezAVLiGSuissaSErnstPRisk of glaucoma in elderly patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids for chronic airflow obstructionPulm Pharmacol Ther2010232657019887116

- NesherRIsrael Glaucoma Screening GroupPrevalence of increased intraocular pressure and optic disk cupping: multicenter glaucoma screening in Israel during the 2009 and 2010 World Glaucoma WeeksIsr Med Assoc J201416848348625269338

- HuertaCGarcía RodríguezLAMöllerCSArellanoFMThe risk of obstructive airways disease in a glaucoma populationPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200110215716311499855

- SorianoJBVisickGTMuellerovaHPayvandiNHansellALPatterns of comorbidities in newly diagnosed COPD and asthma in primary careChest200512842099210716236861

- ZlatevaGPJavittJCShahSNZhouZMurphyJGComparison of comorbid conditions between neovascular age-related macular degeneration patients and a control cohort in the medicare populationRetina20072791292129918046240

- KleinRKnudtsonMDKleinBEPulmonary disease and age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye StudyArch Ophthalmol2008126684084618541850

- SolerNGarcía-HerediaAMarsillachJParaoxonase-1 is associated with corneal endothelial cell alterations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20135485852585823900603

- DoehnerWHaeuslerKGEndresMAnkerSDMacNeeWLainscakMNeurological and endocrinological disorders: orphans in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med2011105Suppl 1S12S1922015080

- CreutzbergECCasaburiREndocrinological disturbances in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J Suppl20034676s80s14621109

- SundarIKYaoHHuangYSerotonin and corticosterone rhythms in mice exposed to cigarette smoke and in patients with COPD: implication for COPD-associated neuropathogenesisPLoS One201492e8799924520342

- DimopoulouIIliasIMastorakosGMantzosERoussosCKoutrasDAEffects of severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on thyroid functionMetabolism200150121397140111735083

- OkutanOKartalogluZOndeMEBozkanatEKunterEPulmonary function tests and thyroid hormone concentrations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMed Princ Pract200413312612815073423

- KaradagFOzcanHKarulABYilmazMCildagOCorrelates of non-thyroidal illness syndrome in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med200710171439144617346957

- ManciniACorboGMGaballoARelationship between plasma antioxidants and thyroid hormones in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseExp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes20121201062362823073919

- BalasubramanianVNaingSHypogonadism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: incidence and effectsCurr Opin Pulm Med201218211211722234275

- KarakouEGlynosCSamaraKDMsaouelPKoutsilierisMVassilakopoulosTProfile of endocrinological derangements affecting PSA values in patients with COPDIn Vivo201327564164923988900

- CorboGMDi Marco BerardinoAManciniASerum level of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and IGF-1 during an acute exacerbation of COPD and their relationships with inflammatory and prognostic indices: a pilot studyMinerva Med2014105428929424844347

- LaghiFAntonescu-TurcuACollinsEHypogonadism in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence and quality of lifeAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171772873315657463

- MousaviSAKouchariMRSamdani-FardSHGilvaeeZNArabiMRelationship between serum levels of testosterone and the severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseTanaffos2012113323525191426

- VertkinALMorgunovLIuShakhmanaevKhAHypogonadism and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseUrologiia20135116118120122 Russian24437255

- ChenYCLinYHChenSHEpidemiology of adrenal insufficiency: a nationwide study of hospitalizations in Taiwan from 1996 to 2008J Chin Med Assoc201376314014523497966

- MartinezCHOkajimaYMurraySCOPDGene InvestigatorsImpact of self-reported gastroesophageal reflux disease in subjects from COPDGene cohortRespir Res2014156224894541

- HardingSMGuzzoMRRichterJE24-h esophageal pH testing in asthmatics: respiratory symptom correlation with esophageal acid eventsChest1999115365465910084471

- EmilssonOIJansonCBenediktsdóttirBJúlíussonSGíslasonTNocturnal gastroesophageal reflux, lung function and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea: Results from an epidemiological surveyRespir Med2012106345946622197048

- MiyazakiMNakamuraHChubachiSKeio COPD Comorbidity Research (K-CCR) GroupAnalysis of comorbid factors that increase the COPD assessment test scoresRespir Res2014151324502760

- AjmeraMRavalADShenCSambamoorthiUExplaining the increased health care expenditures associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease among elderly Medicare beneficiaries with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cost-decomposition analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014933934824748785

- TeradaKMuroSSatoSImpact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease symptoms on COPD exacerbationThorax2008631195195518535116

- BoereeMJPetersFTPostmaDSKleibeukerJHNo effects of high-dose omeprazole in patients with severe airway hyperresponsiveness and (a)symptomatic gastro-oesophageal refluxEur Respir J1998115107010749648957

- MapelDRenal and hepatobiliary dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCurr Opin Pulm Med201420218619324370540

- TerzanoCRomaniSPaoneGContiVOrioloFCOPD and thyroid dysfunctionsLung2014192110310924281671

- DivoMCoteCde TorresJPBODE Collaborative GroupComorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186215516122561964

- KimJLeeJHKimYAssociation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a national cross-sectional cohort studyBMC Pulm Med2013135123927016

- FergusonGTCalverleyPMAndersonJAPrevalence and progression of osteoporosis in patients with COPD: results from the TOwards a Revolution in COPD Health studyChest200913661456146519581353

- CurkendallSMDeLuiseCJonesJKCardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Saskatchewan Canada cardiovascular disease in COPD patientsAnn Epidemiol2006161637016039877

- KellerCAShepardJWChunDSVasquezPDolanGFPulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Multivariate analysisChest19869021851923731890

- FinkelsteinJChaEScharfSMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidityInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009433734919802349

- GudmundssonGGislasonTJansonCDepression, anxiety and health status after hospitalisation for COPD: a multicentre study in the Nordic countriesRespir Med20061001879315893921

- HananiaNAMüllerovaHLocantoreNWEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study investigatorsDeterminants of depression in the ECLIPSE chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183560461120889909

- MapelDWPicchiMAHurleyJSUtilization in COPD: patient characteristics and diagnostic evaluationChest20001175 Suppl 2346S53S10843975

- KühlKSchürmannWRiefWMental disorders and quality of life in COPD patients and their spousesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083472773619281087