Abstract

Melanoma is an immunogenic cancer. However, the ability of the immune system to eradicate melanoma tumors is affected by intrinsic negative regulatory mechanisms. Multiple immune-modulatory therapies are currently being developed to optimize the immune response to melanoma tumors. Two recent Phase III studies using the monoclonal antibody ipilimumab, which targets the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA-4), a negative regulator of T-cell activation, have demonstrated improvement in overall survival of metastatic melanoma patients. This review highlights the clinical trial data that supports the efficacy of ipilimumab, the immune-related response criteria used to evaluate clinical response, and side-effect profile associated with ipilimumab treatment.

Keywords:

Introduction

It has long been understood that among cancer types, melanoma is potentially treatable using immunologically-based therapies. Infiltrating lymphocytes are often present in tumors, demonstrating an immune response to melanoma tumors. However, infiltrating T-cells fail to be sufficiently activated to result in tumor reduction. Methods to enhance the T-cell response to melanoma tumors have shown promise. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with high dose interleukin-2 (IL-2), which stimulates T-cell activity, results in objective response rates of approximately 15% and durable complete response rates in up to 6% of cases.Citation1,Citation2 Adoptive T-cell Transfer (ACT), in which tumor-reactive lymphocytes are stimulated ex vivo and expanded before being re-introduced into the patient, has shown objective response rates of 50%–70%.Citation3,Citation4 Recent data indicates that ACT using lymphodepleting preparative regimens can result in durable complete responses in up to ~20% of patients in a highly selected population.Citation5 Finally, a fully human IgG4 antibody that blocks programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitory receptor on activated T-cells has shown encouraging results in early clinical trials, with 15 of 46 evaluable melanoma patients achieving objective responses in a Phase II study.Citation6 All of these patients remained on trial at the time of presentation, suggesting potential durable responses are obtainable with anti-PD-1 treatment. Despite the potential of enhancing the native immune response to metastatic melanoma tumors, it is clear that there are complexities of the immune response that thwart the ability of T-cells to sufficiently attack melanoma tumors in most patients.

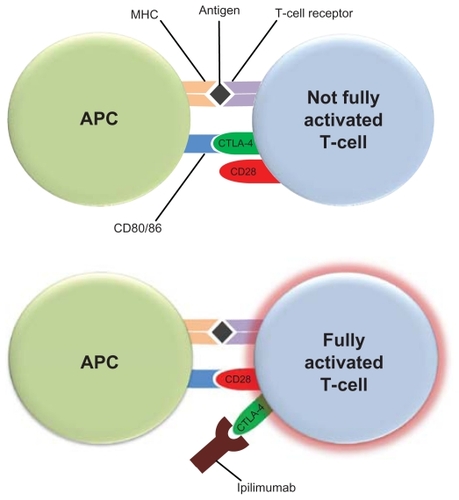

T-cell activation requires costimulatory signals. Melanoma antigens that are bound to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) require the costimulation of CD28 receptor on T-cells by CD80 or CD86 ligands on APCs for T-cell activation (). The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) can bind with greater affinity to CD80 and CD86, and thus disrupt the necessary costimulatory signal provided by APCs. This led to the hypothesis that blockade of CTLA-4 function may allow for optimal costimulation of CD28 receptors on T-cells by APC CD80/86, and enhanced T-cell activation. Ipilimumab (Yervoy™ Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY) is a recombinant human IgG1κ monoclonal antibody that binds to CTLA-4 and blocks binding to CD80 or CD86 on APCs. Multiple elegant pre-clinical and early phase clinical studies demonstrated the proof of principle of this approach,Citation7,Citation8 and ipilimumab is now the first treatment in a randomized study to demonstrate a clear overall survival benefit in metastatic melanoma.Citation9

Figure 1 Ipilimumab blocks the costimulatory signal required for T-cell activation. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) present melanoma antigens bound to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) to T-cells. Costimulation of CD28 receptor on T-cells by CD80 or CD86 ligands on APCs is also required for optimal T-cell activation. The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) on T-cells can bind with greater affinity to CD80 and CD86, and thus disrupt the necessary costimulatory signal provided by APCs. Ipilimumab binds to CTLA-4 and blocks its binding to CD80 or CD86 on APCs allowing for costimulation of CD28 receptors on T-cells by APC CD80/86, and optimal T-cell activation.Citation9,Citation10

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Ipilimumab belongs to a class of immunomodulatory agents which alters the inherent balance of the immune system. It is a monoclonal antibody targeting the immune protein cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA-4). CTLA-4 is a negative regulator of T-cell activation and is expressed on activated T-cells as well as on T-regulatory cells. When T-cells bind to APCs, a costimulatory signal is needed to potentiate T-cell activation. This costimulatory signal takes the form of CD28, present on the T-cell, binding to the B7 family of receptors expressed by APC. CTLA-4 is also capable of binding to B7 receptors and, in doing so, inhibits costimulation and activation of T-cells.Citation10,Citation11 CTLA-4 knockout mice universally experience a fatal syndrome of lymphoproliferation which provides evidence for the key function of CTLA-4 as a negative regulator of the immune system.Citation12–Citation14 Interestingly, blockade of CTLA-4 does not lead to nonspecific T-cell activation but it does appear to augment immune responses in mice.Citation11 Ipilimumab was developed with a transgenic murine model to create a monoclonal antibody with human immunoglobulin genes that binds CLTA-4, and blocks its interactions with B7.Citation15,Citation16

Physical properties

Ipilimumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody with two heavy chains and two kappa light chains linked together by way of disulfide bonds. The molecular weight is approximately 148 kDa and it exists in solution at a physiologic pH of 7.0.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic data was originally generated in mouse and cynomolgus monkey models.Citation15,Citation17 After infusion of a 10 mg/kg dose, the steady-state volume of distribution of ipilimumab was similar to the plasma volume of ipilimumab in cynomolgus monkeys. This implies that ipilimumab remains within the vasculature and does not undergo tissue distribution.Citation18 Ipilimumab is systemically cleared and is not affected by hepatic or renal organ function in patients with a creatinine clearance of ≥29 mL/minute.Citation19 Additionally, it is not metabolized via cytochrome P450 pathways; it is expected to undergo degradation into small peptides and amino acids and undergo excretion via normal protein catabolism. The half-life of the drug is 14.7 days and steady state is established by the third dose when administered every 3 weeks. Pursuant to these studies, a Phase I trial evaluated ipilimumab at 0.3 mg/kg, 1 mg/kg, and 3 mg/kg.Citation20,Citation21

Clinical applications

Phase I trials

The first human clinical studies were initiated at doses of 0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg and studied across a variety of solid tumors.Citation21–Citation23 The 3 mg/kg dose was selected for further testing in humans based upon trough levels. Early studies did not establish a maximum tolerated dose and further clinical studies pushed the dose up to 10 mg/kg. Nonetheless, doselimiting toxicities were noted in nearly all early studies of ipilimumab.Citation21,Citation24 These studies also noted that multiple-dose induction regimens given every 3 weeks improved disease control rates over single-dose induction regimens.Citation25 The most notable responses were seen repeatedly in metastatic melanoma.

Phase II trials in melanoma demonstrate dose-dependent responsiveness

In a Phase II dose-finding study of ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma, responses were noted in a dose-dependent fashion when ipilimumab was dosed at 0.3 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, and 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four doses and analyzed using a statistical trend test.Citation26 Ipilimumab was noted to be clinically active at doses of 3 mg/kg and higher. In a Phase II study of ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg every 4 weeks for four doses alone or in combination with dacarbazine 250 mg/m2/day for 5 days for up to six courses, there was no statistically significant difference in response rate between the two arms (5.4% vs 14.3%, respectively).Citation27 Without a significant increase in toxicity, further studies of ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg showed best overall response rates by WHO modified criteria in the range of 5.8%–15.8%.Citation28,Citation29 An ongoing Phase II single-institution trial (NCT01119508) seeks to further evaluate ipilimumab 10 mg/kg in combination with temozolomide. The primary endpoint of this study is the rate of 6-month progression-free survival with a secondary endpoint of overall response rate. These Phase II studies also evaluated the use of ipilimumab in a maintenance setting after four doses of induction ipilimumab. Patients who did not experience progressive disease after the induction period or toxicity requiring discontinuation of therapy were treated every 12 weeks in a maintenance setting and were continued on therapy until disease progression or unmanageable toxicity occurred (9%–20% of patients).

Phase III trial shows improvement in overall survival in metastatic melanoma

The largest Phase III study completed to date with ipilimumab enrolled 676 patients with previously treated metastatic melanoma and HLA-A*0201-positive class I major histocompatibility complex proteins. The reason for HLA status prerequisite was due to the presence of glycoprotein 100 (gp100) vaccine arms. Gp100 is one of the most common of the melanosomal proteins and is highly immunogenic. Its ability to stimulate tumor-reactive T-cells has been well-described and it was hypothesized that the addition of gp100 peptide vaccine to ipilimumab may enhance T-cell regulation and thus response rate compared with ipilimumab alone.Citation30,Citation31 The gp100 epitope is presented to the immune system in the context of HLA-A*0201 restricted peptides. As a result, patients were randomized in a 3:1:1 fashion to receive either ipilimumab 3 mg/kg plus gp100 peptide vaccine (n = 403), ipilimumab 3 mg/kg alone (n = 137), or gp100 vaccine alone (n = 136). A retrospective analysis of previously published ipilimumab trials in metastatic melanoma noted similar median overall survival rates regardless of HLA status.Citation32 Treatment was administered every 3 weeks for four doses in an induction setting. The primary endpoint of this study was initially designed to evaluate best overall response rate. After emergence of the Phase II data, and in coordination with another Phase III study, the primary endpoint was amended to overall survival (OS). For patients in the ipilimumab arms (alone or with gp100), median OS was 10.1 and 10.0 months, respectively, which was statistically significant compared to median OS of 6.4 months in the gp100 vaccine arm. This study allowed for re-induction ipilimumab in the originally assigned treatment regimen in patients who completed four doses of induction therapy and experienced stable disease or better at week 12 with subsequent disease progression. Thirty-one patients were treated with re-induction ipilimumab (23 with ipilimumab plus gp100 vaccine; eight with ipilimumab alone); 21 patients (67.7%) achieved a response or stable disease with re-induction. On March 25, 2011, on the basis of this Phase III study, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg for four induction doses to treat patients with metastatic melanoma. Due to previously published work, which noted no difference in overall survival or response rate based on HLA status, results of the Phase III trial can be extrapolated to ipilimumab-treated HLA-A*0201-negative patients.Citation32 Another large, international, multi-center Phase III trial (NCT00324155) recently closed to enrollment and sought to compare OS, progression-free survival, and best overall response rate in dacarbazine plus ipilimumab 10 mg/kg vs dacarbazine plus placebo. Eligible patients (n = 502) were treated in the front-line metastatic setting with ipilimumab plus dacarbazine or placebo plus dacarbazine every 3 weeks for four doses followed by maintenance therapy. Although the overall response rate was not notably different between the two groups, the cohort receiving ipilimumab plus dacarbazine had a statistically significant improvement in the primary endpoint of OS compared to placebo plus dacarbazine (11.2 months vs 9.1 months).Citation33

Immune-related response criteria

Patterns of response to immunotherapy such as ipilimumab have historically varied from traditional responses seen with classical cytotoxic therapies. Stabilization of disease or slow regressions of tumors are expected responses; in addition, responses to ipilimumab have been demonstrated after initial tumor flare or tumor inflammation resulting in progressive disease. Likewise, the development of new lesions, while traditionally considered criteria for termination of other treatments, does not always preclude a decrease in overall tumor burden in patients treated with ipilimumab. As such, traditional response criteria (WHO or RECIST) may underestimate the late responses seen with ipilimumab and deem treatment a clinical failure. The immunotherapy community, led by the Cancer Immunotherapy Consortium, previously the Cancer Vaccine Consortium, thereby led a process to review responses to immune-based treatments and establish new criteria which account for delayed response to therapy. This innovative set of criteria is known as immunerelated response criteria (irRC) and is a derivation of WHO criteria ().Citation34 Approximately 8%–10% of patients evaluated in the early Phase II ipilimumab trials had their responses changed from progressive disease to immune-related partial response using irRC.Citation28,Citation29 The Phase III studies of ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma established irRC as the method of response evaluation.

Table 1 Immune-related response criteria

Safety profile

Immune-related adverse events

Ipilimumab induces autoimmune-like adverse events in treated patients. Across early studies, the most commonly encountered immune-mediate effects were dermatitis, hepatitis, enterocolitis, hypophysitis, and uveitis.Citation24,Citation25 These effects are termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs). They appear most often during the induction phase of ipilimumab and were dose-related in early dose-escalation studies.Citation26 Up to 80% of patients on clinical studies of ipilimumab reported irAEs, and 10%–17% of these are grade 3 or higher. The median time to resolution of immune-related adverse events was evaluated in one study and determined to be 6.3 weeks. In the Phase III trial of ipilimumab and gp100, there were 14 deaths overall; eight in the ipilimumab plus gp100 arm, four in the ipilimumab alone arm, and two in the gp100 alone arm. Seven of these 14 were considered to be immune-related and the deaths which have been attributed to ipilimumab involved the gastrointestinal tract (bowel perforation, enterocolitis, liver failure) and the nervous system (Guillain Barré syndrome). The FDA was tasked with balancing safety and adverse events of ipilimumab and created a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program for ipilimumab upon approval. This program educates prescribing healthcare professionals about the risk of potentially severe irAEs that can occur while using ipilimumab.

Correlation between immune-related adverse events and response

Several studies have explored the theory that occurrence of irAE correlates with disease response. The earliest findings noted that patients with autoimmune toxicity were more likely to have tumor regression than patients who did not exhibit autoimmune toxicity (P = 0.008).Citation23 In the Phase I/II study by Weber et al, all four objective responders also had an irAE.Citation24 Additionally, 13 of 14 (93%) patients in this study who experienced stable disease had an irAE. Although the rate of irAE of any grade was 76%, there was no significant correlation between irAEs and response in this study. On further analysis, there was a significant correlation between grade 3 or 4 irAE and response in patients receiving ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg (P = 0.03). Another study found that patients with objective responses were noted to have more severe irAEs, and this finding was significant (P = 0.0004).Citation35 Although many patients with grade 0–2 irAEs experience clinical benefit either via disease stabilization or tumor regression, the disease control rate is higher in patients with grade 3–4 irAEs.Citation29 It should be noted that the correlation between severe irAEs and response is most notable when ipilimumab is administered at 10 mg/kg and this correlation was not described in the Phase III trial which administered ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg.

Side effect management

Bristol-Myers Squibb has developed guidelines to assist health care professionals in the management of immune-mediated adverse reactions based upon affected body region.Citation36 Gastrointestinal toxicity is frequently cited as an irAE that requires management and manifests as diarrhea or enterocolitis. If symptoms are considered moderate, 4–6 stools per day over baseline or associated with abdominal pain, blood or mucus in the stool, ipilimumab should be withheld and antidiarrheal medications utilized until symptoms regress to at least a grade 1. If severe or life-threatening symptoms are present, ≥7 stools per day over baseline or associated with fever, ileus, or suspected bowel perforation, ipilimumab should be permanently discontinued and corticosteroids initiated at 1–2 mg/kg/day prednisone or methylprednisolone tapered slowly over 1 month. Concurrently, consideration of endoscopy is recommended, when appropriate. Systemic steroids should also be considered for the patient experiencing moderate gastrointestinal effects whose symptoms do not respond after 1 week of supportive care.

For patients with immune-mediated dermatitis, nonlocalized rash or diffuse rash ≤50% of skin surface can be managed by withholding ipilimumab and dispensation of topical or systemic corticosteroids. For severe dermatological effects such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, necrotic, bullous, or hemorrhagic desquamation, or full-thickness ulceration, ipilimumab should be permanently discontinued and systemic corticosteroids administered at 1–2 mg/kg/day of prednisone equivalent.

Management of other irAEs such as endocrinopathies driven by hypophysitis, neuropathies, respiratory and ocular manifestations, and hepatitis are also outlined in supplemental information provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb. In general, moderate irAEs can often be managed by withholding ipilimumab with or without supportive care while severe or life-threatening irAEs often warrant permanent discontinuation of ipilimumab along with concurrent immunosuppressive therapy, most often in the form of systemic corticosteroids.

Conclusion

Melanoma is an immunogenic cancer, however, the immune system lacks the inherent capacity to eradicate melanoma tumors in most cases. Methods to enhance the ability of the immune system to attack melanoma have traditionally had marginal success, and served to remind us of the immense complexity of the balance between activating and inhibiting regulators of the immune system. Thus, it is noteworthy that the first randomized study to demonstrate a clear overall survival benefit in metastatic melanoma uses an immune-modulating agent. The effect of ipilimumab on metastatic melanoma is very encouraging and presents many intriguing further questions.

The use of ipilimumab has reinforced the need for oncologists to evaluate “tumor response” in a different manner than that used when using chemotherapeutic agents. Clinical responses can take months to appear given the need for an immune response to self-antigen to develop. Thus criteria, as presented in this review, are now being proposed to account for the difference seen when using immunologically-based therapies. The nature of response criteria will certainly have to be reviewed as new immune-based agents and combination therapies are developed.

Apart from the increase in median survival (approximately 4 months) seen with the use of ipilimumab, is the very encouraging durable complete responses (>5 years) that have been observed in some of the earliest melanoma patients to be treated with ipilimumab. It is clear that immunotherapies (eg, high dose IL-2, adoptive T-cell transfer, anti-PD-1, and anti-CTLA-4) have the capacity to induce a durable complete response in a small subset of patients. It is unclear if patients who have a durable response to one immunotherapy would be more likely to have the same response to another immunotherapy, or if different immune-modulating agents can have a beneficial effect in different populations of patients. The development of markers that predict which patients will respond to treatment and which will not, will also serve to optimize the use of these immune-modulating agents while limiting unnecessary toxicity.

The identification of activating gene mutations (eg, BRAF, NRAS, KIT, GNAQ, GNA11) in different subtypes of melanoma has created the opportunity to identify and inhibit activated growth and survival signaling pathways within melanoma tumor cells.Citation37,Citation38 It will be intriguing to see if the combination of immunotherapies with agents that target particular signaling pathways will enhance clinical response and overall survival, and most importantly long-term survival. Results from recent clinical trials have shown the efficacy of using small molecule inhibitors to target particular signaling pathway molecules. Vemurafenib, a BRAF mutant specific inhibitor recently gained FDA approval for use in advanced melanoma harboring the V600 mutation.Citation39 Multiple reports have demonstrated clinical responses using a variety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib, dasatinib, sunitinib) in KIT mutant melanoma.Citation40–Citation43 Likewise, early reports suggest that small molecule MEK inhibitors that are currently being evaluated in clinical trials may have efficacy in different subtypes of melanoma.Citation44

The recent FDA-approval of ipilimumab for unresectable or metastatic melanoma is a major advance in the treatment of melanoma, and will undoubtedly serve as the foundation of future treatment regimens.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AtkinsMBLotzeMTDutcherJPHigh-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993J Clin Oncol19991772105211610561265

- SmithFODowneySGKlapperJATreatment of metastatic melanoma using interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with vaccinesClin Cancer Res200814175610561818765555

- DudleyMEYangJCSherryRAdoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimensJ Clin Oncol200826325233523918809613

- BesserMJShapira-FrommerRTrevesAJClinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short-term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patientsClin Cancer Res20101692646265520406835

- RosenbergSAYangJCSherryRMDurable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma Using T cell transfer immunotherapyClin Cancer Res201117134550455721498393

- SznolMPowderlyJDSmithDCSafety and antitumor activity of biweekly MDX-1106 (Anti-PD-1, BMS-936558/ONO-4538) in patients with advanced refractory malignancies [abstract]J Clin Oncol20102815s2506

- WeberJImmune checkpoint proteins: a new therapeutic paradigm for cancer – preclinical background: CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockadeSemin Oncol201037543043921074057

- CurranMAMontalvoWYagitaHAllisonJPPD-1 and CTLA-4 combination blockade expands infiltrating T cells and reduces regulatory T and myeloid cells within B16 melanoma tumorsProc Natl Acad Sci U S A201010794275428020160101

- HodiFSO’DaySJMcDermottDFImproved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanomaN Engl J Med2010363871172320525992

- LeeKMChuangEGriffinMMolecular basis of T cell inactivation by CTLA-4Science19982825397226322669856951

- EgenJGKuhnsMSAllisonJPCTLA-4: new insights into its biological function and use in tumor immunotherapyNat Immunol20023761161812087419

- TivolEABorrielloFSchweitzerANLynchWPBluestoneJASharpeAHLoss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4Immunity1995355415477584144

- WaterhousePPenningerJMTimmsELymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4Science199527052389859887481803

- ChambersCASullivanTJAllisonJPLymphoproliferation in CTLA-4-deficient mice is mediated by costimulation-dependent activation of CD4+ T cellsImmunity1997768858959430233

- KelerTHalkEVitaleLActivity and safety of CTLA-4 blockade combined with vaccines in cynomolgus macaquesJ Immunol2003171116251625914634142

- MorseMATechnology evaluation: ipilimumab, Medarex/Bristol-Myers SquibbCurr Opin Mol Ther20057658859716370382

- PalmisanoGLTazzariPLCozziEExpression of CTLA-4 in nonhuman primate lymphocytes and its use as a potential target for specific immunotoxin-mediated apoptosis: results of in vitro studiesClin Exp Immunol2004135225926614738454

- Anonymous (Study No. DS06064: BMS-663513 and BMS-734016 (MDX-010): One-month Intravenous Combination Toxicity Study in MonkeysBristol-Myers Squibb Company2007

- KohnDBDottiGBrentjensRCARs on track in the clinicMol Ther201119343243821358705

- SandersonKScotlandRLeePAutoimmunity in a phase I trial of a fully human anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 monoclonal antibody with multiple melanoma peptides and Montanide ISA 51 for patients with resected stages III and IV melanomaJ Clin Oncol200523474175015613700

- MakerAVPhanGQAttiaPTumor regression and autoimmunity in patients treated with cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and interleukin 2: a phase I/II studyAnn Surg Oncol200512121005101616283570

- PhanGQYangJCSherryRMCancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanomaProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2003100148372837712826605

- AttiaPPhanGQMakerAVAutoimmunity correlates with tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4J Clin Oncol200523256043605316087944

- WeberJSO’DaySUrbaWPhase I/II study of ipilimumab for patients with metastatic melanomaJ Clin Oncol200826365950595619018089

- MakerAVYangJCSherryRMIntrapatient dose escalation of anti-CTLA-4 antibody in patients with metastatic melanomaJ Immunother200629445546316799341

- WolchokJDNeynsBLinetteGIpilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging studyLancet Oncol201011215516420004617

- HershEMO’DaySJPowderlyJA phase II multicenter study of ipilimumab with or without dacarbazine in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced melanomaInvest New Drugs201129348949820082117

- O’DaySJMaioMChiaron-SileniVEfficacy and safety of ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a multicenter single-arm phase II studyAnn Oncol20102181712171720147741

- WeberJThompsonJAHamidOA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of ipilimumab administered with or without prophylactic budesonide in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanomaClin Cancer Res200915175591559819671877

- ParkhurstMRSalgallerMLSouthwoodSImproved induction of melanoma-reactive CTL with peptides from the melanoma antigen gp100 modified at HLA-A*0201-binding residuesJ Immunol19961576253925488805655

- KawakamiYRobbinsPFWangXIdentification of new melanoma epitopes on melanosomal proteins recognized by tumor infiltrating T lymphocytes restricted by HLA-A1, -A2, and -A3 allelesJ Immunol199816112698569929862734

- WolchokJDWeberJSHamidOIpilimumab efficacy and safety in patients with advanced melanoma: a retrospective analysis of HLA subtype from four trialsCancer Immun201010920957980

- RobertCThomasLBondarenkoIIpilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanomaN Engl J Med2011364262517252621639810

- WolchokJDHoosAO’DaySGuidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteriaClin Cancer Res200915237412742019934295

- DowneySGKlapperJASmithFOPrognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockadeClin Cancer Res20071322 Pt 16681668817982122

- YERVOY™ (ipilimumab) Immune-mediated Adverse Reaction Management GuideFDA-approved REMS Available at: http://www.yervoy.com/hcp/index.aspxAccessed November 23, 2011

- FlahertyKTFisherDENew strategies in metastatic melanoma: oncogene-defined taxonomy leads to therapeutic advancesClin Cancer Res201117154922492821670085

- WoodmanSEDaviesMATargeting KIT in melanoma: a paradigm of molecular medicine and targeted therapeuticsBiochem Pharmacol201080556857420457136

- FlahertyKTPuzanovIKimKBInhibition of Mutated, Activated BRAF in Metastatic MelanomaN Engl J Med2010363980981920818844

- CarvajalRDAntonescuCRWolchokJDKIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanomaJAMA2011305222327233421642685

- WoodmanSETrentJCStemke-HaleKActivity of dasatinib against L576P KIT mutant melanoma: molecular, cellular, and clinical correlatesMol Cancer Ther2009882079208519671763

- KlugerHMDudekAZMcCannCA phase 2 trial of dasatinib in advanced melanomaCancer2010117102202220821523734

- SatzgerIKuttlerUVolkerBSchenckFKappAGutzmerRAnal mucosal melanoma with KIT-activating mutation and response to imatinib therapy – case report and review of the literatureDermatology20102201778119996579

- AdjeiAACohenRBFranklinWPhase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in Patients With Advanced CancersJ Clin Oncol200826132139214618390968