Abstract

The treatment of sarcoidosis is not standardized. Because sarcoidosis may never cause significant symptoms or organ dysfunction, treatment is not mandatory. When treatment is indicated, oral corticosteroids are usually recommended because they are highly likely to be effective in a relative short period of time. However, because sarcoidosis is often a chronic condition, long-term treatment with corticosteroids may cause significant toxicity. Therefore, corticosteroid sparing agents are often indicated in patients requiring chronic therapy. This review outlines the indications for treatment, corticosteroid treatment, and corticosteroid sparing treatments for sarcoidosis.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown cause. The disease most commonly affects the lung, but any organ can be involved.Citation1 Sarcoidosis has a variable natural course from an asymptomatic state to a progressive disease, that, on occasion, may be life threatening. Treatment decisions concerning sarcoidosis are problematic for many reasons. First, treatment is often associated with significant side effects. Therefore, treatment may cause more harm than the disease, especially since sarcoidosis may never cause significant symptoms. Second, although sarcoidosis is often well controlled with corticosteroids, many corticosteroid side effects result from chronic use. Therefore, even when sarcoidosis is well controlled with corticosteroids, corticosteroid-sparing medications may be required over time. Third, the treatment of sarcoidosis varies, to some degree, depending on the organ or organs that may be involved. Fourth, because sarcoidosis is not a common disease, minimal evidence-based data exist on which to support treatment decisions. This paper will discuss the decision to treat, drug therapies, and drug toxicities for sarcoidosis. Emphasis will be placed on emerging potential therapies for this disease.

The decision to treat sarcoidosis

The decision to treat sarcoidosis is a complex one. As mentioned, the disease is often self-limiting and sarcoidosis pharmacotherapy is associated with significant side effects. In this section, some general points concerning the decision to treat sarcoidosis will be addressed.

The treatment of asymptomatic sarcoidosis

In general, asymptomatic sarcoidosis should not be treated.Citation2,Citation3 Many of these patients have minimal physiologic impairment from sarcoidosis; that is the explanation for the disease causing no symptoms. These patients often have an excellent prognosis and never develop symptomatic disease or significant organ dysfunction. The risks of subjecting such patients to anti-sarcoidosis therapy, particularly, corticosteroid therapy, usually outweigh the benefits of treatment. It is important to carefully monitor untreated patients for the development of significant symptoms or organ dysfunction that would necessitate therapy. In general, preemptive therapy is not indicated because the granulomatous inflammation from sarcoidosis is often completely reversible, with or without therapy. A potential criticism of this approach is that unchecked granulomatous inflammation can lead to fibrosis and scar formation that is usually irreversible. Although, theoretically, preemptive therapy could avoid such fibrosis, practically speaking, such fibrosis usually requires some months of active disease that usually causes significant symptoms. Specifically, asymptomatic lung, liver, splenic, bone, intrathoracic, and intraabdominal lymph node sarcoidosis involvement very rarely requires treatment.

There are some exceptions to the premise of avoiding treatment of asymptomatic sarcoidosis. Asymptomatic ocular sarcoidosis, especially in the form of sarcoid uveiits, should be treated because it may lead to permanent vision impairment.Citation4 For this reason, all patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis should undergo an ophthalmologic evaluation, even if they have no eye symptoms.Citation1 Asymptomatic disorders of calcium dysregulation from sarcoidosis could also be considered for treatment. The pathological lesion of sarcoidosis is the granuloma that contains antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages.Citation5 These APCs contain the enzyme, 1-alpha hydroxylase, which hydroxylates 25-hydroxy vitamin D to 1, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D, the active form of the vitamin that can lead to hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and renal insufficiency.Citation6,Citation7 Asymptomatic nephrolithiasis and renal insufficiency from sarcoidosis should be treated. Mild hypercalcemia that causes no symptoms should probably also be treated, although, often, the serum calcium will return to the normal range with adequate hydration and avoidance of a high-calcium diet.Citation8 Asymptomatic hypercalciuria from sarcoidosis does not necessarily require treatment if there is no evidence of hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, or renal insufficiency. Certainly, such patients are at increased risk of developing renal problems, and they should be adequately hydrated, avoid excessive calcium intake, and have their renal function carefully monitored. The treatment of asymptomatic cardiac sarcoidosis and neurosarcoidosis is very controversial, as these two forms of sarcoidosis are potentially life-threatening. One study of cardiac sarcoidosis patients found that those without symptoms had an excellent prognosis. However, very few such patients were identified.Citation9 Although there is inadequate medical evidence to support a specific approach, we believe that it is not a mandatory requirement to treat asymptomatic cardiac or neurosarcoidosis. We believe that each patient should be evaluated individually, with the decision to treat based on the specific clinical findings (eg, cardiac: presence/absence of sustained ventricular tachycardia/malignant arrhythmias, myocardial performance; neurologic: change in the size of the lesion[s]).

The treatment of multiple organs

Sarcoidosis often involves multiple organs that may cause treatment decisions to appear complex. We believe that it is essential that treatment decisions concerning sarcoidosis should focus on the treatment indications for each organ in isolation. It is our experience that clinicians may be “overwhelmed” by the number of organs involved, and, in this situation, administer treatment for “systemic sarcoidosis” when a careful analytic approach would suggest there is no specific indication for treatment. When a decision is made to treat sarcoidosis based on specific criteria for specific organ involvement, endpoints for each of these organs should be determined so that therapy can be adjusted in a rational way.

The relationship of disease activity to treatment

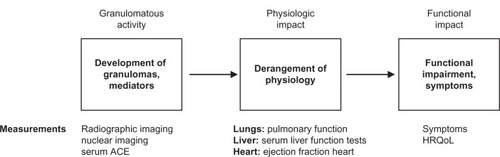

The presence of granulomas from sarcoidosis defines the disease as active. These granulomas deposit in various organs and have the potential to cause organ dysfunction. However, these granulomas may spontaneously remit or cause minimal organ damage, leaving the patient’s quality of life unaffected. outlines the general schema of how the granulomatous inflammation of sarcoidosis may affect patients. Many laboratory tests are available to assess disease activity in sarcoidosis, including serum angiotensin-converting enzyme levels and various body scanning techniques. However, in general, the presence of disease activity is a necessary but insufficient criterion on which to base therapy of sarcoidosis.Citation3 Rather, the treatment of sarcoidosis should be focused on improving the patient’s quality of life.Citation3 Therefore, the results of these aforementioned tests of disease activity should not be used to guide therapy. Despite the insufficiency of these tests to determine the need for therapy, evidence of granulomatous inflammation is a necessary requirement for therapy. This is because some sarcoidosis patients have an impaired quality of life from previously active sarcoidosis, which has resulted in permanent fibrosis but without evidence of active granulomatous inflammation. Such patients do not require therapy as there is no remaining active disease to treat.

Figure 1 The pathway from granulomatous inflammation to symptoms in sarcoidosis.

Adapted with permission from Judson MA. The treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2012;106(10):1351–1361.Citation3

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

The decision to treat pulmonary sarcoidosis

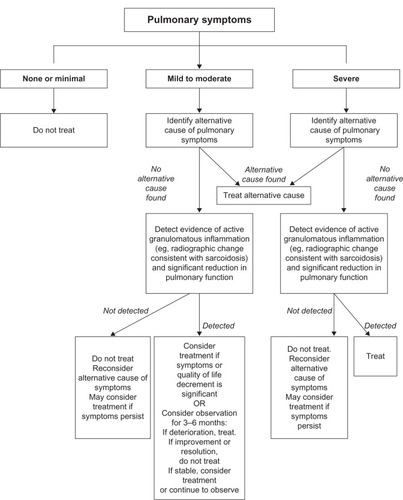

Because the lung is the most common organ involved with sarcoidosis and is the most common reason to treat sarcoidosis, the decision to treat pulmonary sarcoidosis in relation to will be discussed. Pulmonary sarcoidosis is problematic to assess, because the appropriate endpoints on which to initiate and adjust therapy are unclear. As mentioned previously, pulmonary symptoms may be discordant with tests reflective of granulomatous inflammation (eg, lung imaging studies) and physiologic impairment (eg, pulmonary function testing) (). It is our opinion that treatment should be based primarily on pulmonary symptoms that are thought to be reflective of pulmonary sarcoidosis.Citation3 Measurement of pulmonary function tests may be important to support that pulmonary symptoms are caused by pulmonary sarcoidosis. Since chest imaging reflects the granuloma burden, which usually correlates poorly with physiologic change and symptoms related to pulmonary sarcoidosis,Citation10 it is not routinely used to determine when to initiate therapy. However, chest imaging should be performed to assess the need for therapy of pulmonary sarcoidosis mainly to exclude alternative cardiopulmonary conditions that could be causing the pulmonary symptoms.Citation3 Our general approach to the decision to treat pulmonary sarcoidosis is outlined in .

Figure 2 The general approach to the decision to treat pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Adapted with permission from Judson MA. The treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2012;106(10):1351–1361.Citation3

Corticosteroid therapy

Corticosteroid therapy is considered first line therapy for acute and chronic sarcoidosis in which a decision is made to treat.Citation1–Citation3 Despite the nearly universal opinion that corticosteroids are the drug of choice for almost all forms of sarcoidosis, no pharmacologic treatments for sarcoidosis have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Corticosteroids act mainly by repression of inflammatory genes including interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha that are important cytokines in the development of the sarcoid granuloma.Citation11,Citation12 A number of additional inflammatory cytokines that are involved in granuloma formation and maintenance are responsive to the anti-inflammatory properties of corticosteroids.Citation12

There is no prospective data to guide the dose, duration, or tapering of corticosteroids in sarcoidosis. Guiding principles are offered in the official sarcoidosis consensus statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS)/World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases (WASOG).Citation1

Pulmonary sarcoidosis

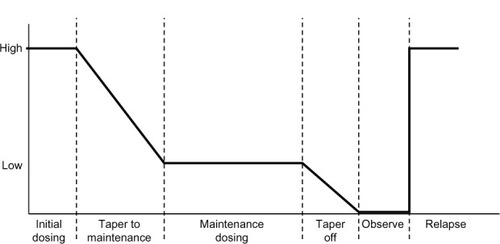

A Delphi study of sarcoidosis experts reached a consensus that corticosteroids are the drug of choice for pulmonary sarcoidosis.Citation13 The ATS/ERS/WASOG consensus recommends a daily prednisone equivalent of 20–40 mg for the initial treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis. This dose should be continued for at least 1–3 months and then tapered to a 5–10 mg/day maintenance dose for a total of 1 year of treatment before discontinuing.Citation1 The rationale for a 1-year regimen is empiric and based on the unproven assumption that relapses are common with shorter-course regimens. This approach to treatment has been described as “the six phases of treatment for pulmonary sarcoidosis:” initial dosing, taper to maintenance, maintenance dosing, taper off, observation, treatment of relapse ().Citation2 The suggested corticosteroid doses and dosing intervals are described in the text of . Several variations of treatment have been suggested such as: total duration of therapy for 6 months, maintenance phase where alternate day therapy is used to decrease side effects, and a lower initial dose and shorter initial phase.Citation3 In general, in contrast to other organs involved with sarcoidosis (vide infra), pulmonary sarcoidosis is usually very sensitive to corticosteroid therapy.

Figure 3 Corticosteroid (six-phase) treatment for pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Reproduced with permission from Judson MA. An approach to the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis with corticosteroids: the six phases of treatment. Chest. 1999;115(4):1158–1165.Citation2

Although treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) has been studied, these data are inconclusive. ICS have been advocated for sarcoidosis associated cough, although definite improvement of this symptom has not been demonstrated.Citation14 In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 189 patients with recent-onset pulmonary sarcoidosis, subjects received either 3 months of systemic corticosteroids (20 mg/day of prednisolone tapering to 10 mg/day) followed by 15 months of high-dose inhaled budesonide (800 μg twice daily), or matching oral and inhaled placebos. After 5 years, statistically more patients in the placebo group had evidence of chest radiographic changes and more frequently required oral corticosteroids.Citation15 Although this study was well designed, these results are discordant with several studies suggesting that corticosteroid treatment of sarcoidosis is associated with a greater risk of relapse.Citation16–Citation19 In addition, this was not a “pure ICS” study in that the treatment group also initially received 3 months of oral corticosteroids. Finally, the dose of ICS used in this trial was budesonide 800 μg twice daily, which is costly within the US. A meta-analysis concerning ICS treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis did not clearly demonstrate a benefit.Citation20 The aforementioned Delphi study of sarcoidosis experts reached a consensus that ICS should not be used routinely to treat pulmonary sarcoidosis.Citation13 ICS could be considered on an individual basis for pulmonary sarcoidosis patients with significant cough, or possibly, as an oral corticosteroid sparing agent.

Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis

Corticosteroids are also the initial drug of choice to treat most forms of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. As a general rule, 20–40 mg of daily prednisone equivalent is an adequate initial dose for most forms of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. The corticosteroid dose should then be tapered to the lowest effective dose, with a specific clinically relevant endpoint in mind (). Some nuances in the exact dosing schedules and type of corticosteroid, depending on the specific organ that is treated, will be discussed in the next section.

Eye

Sarcoidosis may cause an isolated anterior uveitis confined to the anterior chamber. Because topical corticosteroids (corticosteroid eyedrops) can penetrate into the anterior chamber, they can be used without oral corticosteroids in this instance.Citation21 If there is an associated intermediate and/or posterior uveitis, topical corticosteroids will be inadequate and oral corticosteroids will be required. Intraocular corticosteroid injections may be given when eye sarcoidosis extends deeper than the anterior chamber.Citation4 There is minimal evidence to support a specific approach, but most recommend a shorter course (eg, 3–6 months) of monotherapy with corticosteroids for sarcoid uveitis because both the disease itself and corticosteroid therapy can lead to cataracts and glaucoma. Therefore, corticosteroid-sparing agents are considered earlier than with other forms of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis may cause an acute optic neuritis which is vision-threatening. A sarcoidosis patient who develops sudden loss of vision or color vision should have this diagnosis immediately confirmed via a fundoscopic examination. If an acute sarcoid optic neuritis is confirmed, high dose intravenous corticosteroids (eg, 1 g daily of methylprednisolone sodium succinate for 3–5 days) should be strongly considered.

Cardiac

Although some have recommended high initial corticosteroid doses for cardiac sarcoidosis,Citation22 many recommend 30 mg of daily prednisone equivalent based on a Japanese series that found no difference in long-term survival between those who received at least 40 mg of prednisone daily compared with those receiving 30 mg/day or less.Citation23 A Delphi study of cardiac sarcoidosis experts reached consensus that 30–40 mg of daily prednisone equivalent be the initial treatment dose cardiac sarcoidosis.Citation24

Neurosarcoidosis

Neurosarcoidosis is relatively refractory to corticosteroids. There are case series demonstrating up to 71 percent of patients being refractory to corticosteroidsCitation25 and relapses being common at 20–25 mg of daily prednisone equivalent.Citation26 For these reasons, some have recommended that the initial corticosteroid dose for neurosarcoidosis should be 40–80 mg of daily prednisone equivalent.Citation27

Skin

Cutaneous sarcoidosis almost never causes significant medical problems, and is, therefore, treated only if it is of cosmetic importance to the patient. The initial corticosteroid dose is 20–40 mg of daily prednisone equivalent. For one or a few small lesions, intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide are often effective.Citation28,Citation29 Topical corticosteroid creams may be used in this case, although they are probably not as effective as intralesional injections.Citation29 Lupus pernio is a disfiguring facial form of cutaneous sarcoidosis. Although lupus pernio lesions usually improve on corticosteroid therapy, these lesions usually require infliximab therapy (vide infra) for significant resolution.

Joint

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be used prior to consideration of corticosteroid or other immunosuppressive therapy.

Monitoring

Patients receiving chronic corticosteroids need to be monitored for potential side effects. This includes monitoring weight and nutrition, blood pressure, cortical bone density, eye examinations (for the development of cataracts and/or glaucoma), diabetes mellitus/hyperglycemia, and mood changes. Prophylaxis against infection with Pneumocystis jirovecii is somewhat controversial as some experts have recommended therapy but this seems to be a rare event.Citation30

Additional anti-sarcoidosis agents

When to consider additional agents

Although corticosteroids are the initial drug of choice for almost all forms of sarcoidosis, additional agents are very commonly required. It is unusual for sarcoidosis to be unresponsive to corticosteroids. This may occasionally occur in cases of neurosarcoidosis,Citation25 but almost never with pulmonary sarcoidosis or other forms of sarcoidosis. It is much more common for additional medications to be required because of the development of significant corticosteroid side effects. These corticosteroid side effects may present acutely with initial high dose corticosteroid treatment, such as mood and behavioral changes. Most commonly, these corticosteroid side effects develop slowly, as most of these side effects are the result of cumulative toxicity (eg, osteoporosis, weight gain). Therefore, patients with chronic sarcoidosis who need anti-sarcoidosis medication for long periods are at particular risk for corticosteroid toxicity, even if their sarcoidosis is being controlled on a relatively low dose of corticosteroids. A Delphi study of sarcoidosis experts reached a consensus that a maintenance dose of greater than 10 mg of daily prednisone equivalent was unacceptable, implying that corticosteroid sparing agents should be considered in such situations.Citation13

In most situations, additional agents are added to corticosteroid therapy as corticosteroid sparing agents with the goal of reducing the chronic corticosteroid dose. Additional agents are infrequently sufficient to control sarcoidosis without the addition of at least small doses of corticosteroids. Corticosteroids are usually tapered to the lowest effective dose once these agents have been added. With the possible exception of infliximab,Citation31 most of these additional agents take several months to be maximally effective. Therefore, too rapid a corticosteroid taper after additional agents have been added may falsely label these drugs as ineffective as corticosteroid sparing medications. Unless the corticosteroid side effects are major, it is recommended that corticosteroids not be tapered for at least 1 month after the addition of a second agent. As the above implies, complete discontinuation of corticosteroids is much less likely to be successful than tapering corticosteroids to a lower maintenance dose.

The rationale for selecting a specific additional drug for the treatment of sarcoidosis is problematic, as these data are limited, usually consist of uncontrolled case reports or case series, and have almost never involved head to head comparisons or randomized controlled trials. This decision is often based on the following factors: (1) the organ that is being treated, as some case reports and case series have involved specific sarcoidosis organ involvement; (2) the risk of drug toxicity in the individual patient; (3) ease of use; (4) cost. Although not evidence-based, two Delphi studies of sarcoidosis experts suggested favored drug choices for the treatment of pulmonaryCitation13 and cardiacCitation24 sarcoidosis.

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is the most studied alternative medication to corticosteroids for the treatment of sarcoidosis. In a recent Delphi study of sarcoidosis experts, a consensus was reached that methotrexate was the preferred corticosteroid sparing agent for pulmonary sarcoidosis.Citation13 Methotrexate acts by inhibiting the metabolism of folic acid.

Methotrexate has been found to have efficacy for most forms of sarcoidosis including lung, eye, skin, and neurologic involvement.Citation32 Approximately two-thirds of sarcoidosis patients will respond to treatment.Citation33 We believe that methotrexate is most useful in sarcoidosis as a corticosteroid sparing agent when corticosteroids have either been inadequate to completely control the disease and/or caused significant side effects. In approximately one-quarter of cases, sarcoidosis patients receiving methotrexate and corticosteroids can be weaned off the latter drug.Citation32

The standard dose of methotrexate is from 10–25 mg weekly, although most clinicians use the lower end of that range (10–15 mg/week).Citation34 Folic acid is often administered concomitantly.Citation35

Nausea, malaise, and leucopenia are the most common adverse effects of methotrexate. Hepatotoxicity causing hepatic fibrosis, pulmonary toxicity, and opportunistic infections may also occur with this drug. The pregnancy risk of methotrexate is category X: it should not be used during pregnancy.

Antimalarials

Antimalarial agents such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have immunomodulating properties, and they have been found to be effective in the treatment of sarcoidosis. The proposed mechanism of action includes the impairment of release of several cytokines and impaired antigen presentation by monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells to CD4-positive helper T-cells.Citation36 Chloroquine has shown benefit in the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis but the data are quite limited.Citation37 Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine appear particularly effective for cutaneous sarcoidosis where they have been used as monotherapy or in combination with corticosteroids.Citation38 Since the antimalarials may take several months to be maximally effective, we recommend using them for cutaneous sarcoidosis along with corticosteroids as the latter drug usually works much more rapidly. Attempts can be made to taper, if not discontinue corticosteroids over several months. Sarcoidosis-induced hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria have also been reported to respond to antimalarials,Citation39–Citation41 although in our experience, corticosteroids work more reliably for this problem. Antimalarials are also useful for the treatment of sarcoidosis-related arthritis.Citation42

The major side effect of the antimalarials, especially chloroquine, is retinopathy. Therefore, a baseline eye exam and follow-up exam every 6–12 months is requisite. Additional side effects include nausea, agranulocytosis, and hemolysis in patients with glucose-6-phosphate deficiency. Hydroxychloroquine has a much smaller risk of retinal toxicity compared with chloroquine, but the latter drug appears more effective.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is an anti-metabolite drug, which has been reported to be useful in the treatment of sarcoidosis. Azathioprine is a prodrug that is converted in vivo to the active metabolite, 6-mercaptopurine by the enzyme, thiopurine-S-methyltransferase. As a purine analog, azathioprine acts to inhibit purine synthesis necessary for the proliferation of cells, especially B and T lymphocytes. Cellular immunity is suppressed to a greater degree than humoral immunity.

Azathioprine’s strong suppressive effect on T-lymphocytes makes it an attractive treatment option for sarcoidosis, in which activated T-cells play a critical role. However, the usefulness of azathioprine for sarcoidosis has yet to be examined through a randomized controlled clinical trial. Most reports of azathioprine for the treatment of sarcoidosis have involved open label case series with a small number of patients. We believe that azathioprine is most likely to be useful in sarcoidosis as a corticosteroid sparing agent when corticosteroids have either been inadequate to completely control the disease and/or caused significant side-effects.

Azathioprine is usually initiated at a dose of 50 mg per day. Increasing the dose by 25 mg/day every 2–3 weeks reduces the likelihood of gastrointestinal side effects. The typical maintenance dose is 2 mg/kg with a maximum of 200 mg/day. Dosing adjustments are made for renal insufficiency and/or adverse effects such as leukopenia. An initial clinical response usually occurs within 2–4 months.Citation43

The major adverse effects of azathioprine include hematologic, gastrointestinal, and hepatotoxicity, a hypersensitivity syndrome, and carcinogenic and teratogenic risks. Women of childbearing age must use a reliable method of contraception during azathioprine therapy. Gastrointestinal upset, rash, fever, and malaise are the most common symptoms reported by patients. Azathioprine-induced hepatotoxicity is generally reversible following discontinuance of the drug. Complete blood counts and serum liver tests should be regularly monitored for drug toxicity.

Leflunomide

Leflunomide was originally developed as an analogue to methotrexate with less toxicity. It has been suggested to be useful for sarcoidosis in several case series. The active metabolite of leflunomide (A77 1726) exhibits anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and causes immunomodulation via its inhibition of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, an enzyme responsible for de novo synthesis of pyrimidines.Citation44 Ultimately, the drug prevents the expansion of activated lymphocytes via interference with cell cycle progression. Leflunomide also suppresses TNF-α signaling.

Limited clinical data suggest that leflunomide may be as effective as methotrexate in patients with chronic sarcoidosis, but with less toxicity.Citation45 The drug could be considered in sarcoidosis as a corticosteroid sparing agent when corticosteroids have either been inadequate to completely control the disease and/or caused significant side-effects. We suspect that it would be particularly useful in a sarcoidosis patient who received a beneficial response from methotrexate but developed a side effect from this drug.

The initial dose of leflunomide is typically 20 mg per day. The dosage may be decreased to 10 mg/day in patients who develop toxicity. Some have recommended administering a loading dose of 100 mg daily for 3 days as the drug has a long half-life (typically 14–15 days) and takes a long time to achieve steady state levels.Citation46 However, a loading dose is often omitted due to a greater incidence of side effects, especially in patients who are receiving the drug because of previous hepatic or hematologic toxicity from methotrexate use.Citation47

As mentioned, previous trials (in rheumatoid arthritis) demonstrated that leflunomide had a superior side effect profile compared to methotrexate.Citation48 Significant hepatic toxicity requiring drug withdrawal occurred at half the rate in the leflunomide group compared to those receiving methotrexate. Interstitial pneumonitis did not occur with leflunomide whereas it was seen in 5/320 (1.6%) patients who received methotrexate that resulted in one death.Citation48 The most common side effects of leflunomide are nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain, rash, alopecia, and peripheral neuropathy. Anemia occurs in 1%–10%. Leflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy (category X). Pregnancy must be excluded prior to initiating treatment. Contraception is required in both males and females of childbearing potential. Because the drug has a typical half-life of 14–15 days, if significant leflunomide toxicity develops, elimination may need to be enhanced by the administration of cholesytramine.Citation49

Mycophenolate

Mycophenolate mofetil is a reversible inhibitor of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase in purine biosynthesis that is necessary for the growth of T cells and B cells. It is a prodrug of mycophenolic acid.

Mycophenolate has not been used extensively for the treatment of sarcoidosis. It may be most useful for the treatment of neurosarcoidosisCitation50 and cutaneous sarcoidosis.Citation51 It may also be useful for other forms of sarcoidosis, although the data are quite limited.Citation51,Citation52 We believe that the data concerning this drug are so minimal for the treatment of sarcoidosis that it should be considered as a third-line drug in sarcoidosis as a corticosteroid sparing agent when (a) corticosteroids have either been inadequate to completely control the disease and/or caused significant side-effects, and (b) other standard corticosteroid sparing agents have failed or have caused significant side effects. Mycophenolate might be more highly considered for cases of neurosarcoidosis.

The maintenance mycophenolate dose in sarcoidosis is usually 1000–1500 mg given twice daily (2–3 g total daily dose).Citation50,Citation51 The dose is often escalated toward this maintenance dose while monitoring for toxicity such as cytopenias of serum liver enzyme elevations.Citation50

The most common side effects of this drug are hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia and GI side-effects such as diarrhea and vomiting. Bone marrow suppression and hepatic dysfunction may occur. Mycophenolate is contraindicated in pregnancy as it is associated with fetal loss and congenital birth defects.

Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent that prevents cell division by cross-linking DNA strands and decreasing DNA synthesis. Its immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects arise from a decrease in lymphocyte number and function.

Because of the risk of severe toxicity (vide infra) cyclophosphamide is used to treat sarcoidosis only in severe cases that have been refractory to corticosteroids and, usually, additional agents. In particular, cyclophosphamide has been used to treat neurosarcoidosisCitation25,Citation53 and cardiac sarcoidosisCitation54,Citation55 because these forms of sarcoidosis may be life threatening. Even in some of these cases, infliximab is preferred and probably superior to cyclophosphamide.Citation56

Cyclophosphamide is usually given intravenously rather than orally as the side effect profile is better with the former route of administration. Intravenous regimens are associated with approximately 50% less cumulative cyclophosphamide than oral daily dosing and therefore less toxicity.Citation57 The usual intravenous dose is 500–1000 mg administered over 30–60 minutes once every 2–4 weeks.Citation25,Citation53 Alternatively, a body surface area approach may be used with 0.5 gm/m2 of body surface area administered intravenously every 4 weeks.Citation57

Cyclophosphamide may cause toxicity of the hematologic, dermatologic, metabolic, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems. Cyclophosphamide therapy, especially when oral and long-term, is associated with hemorrhagic cystitis as well as the development of transitional-cell carcinoma bladder. Cyclophosphamide interferes with oogenesis and spermatogenesis and may cause sterility in both men and women. Cyclophosphamide may also be teratogenic. Women of childbearing age must use a reliable method of contraception while receiving cyclophosphamide.Citation58

Tumor necrosis alpha antagonists

Over the past several years, various series and clinical trials have reported efficacy of TNF-α antagonists for the treatment of sarcoidosis.Citation31,Citation59–Citation62 There is a sound rationale for this therapy because TNF-α is secreted by macrophages in patients with active sarcoidosis,Citation63 and TNF-α is thought to be integrally involved in the development of the sarcoid granuloma.Citation64

In a randomized, double-blinded clinical trial, infliximab was shown to be effective for pulmonaryCitation31 and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis.Citation65 It may be particularly effective for lupus pernioCitation66 (disfiguring facial sarcoidosis) and for neurosarcoidosis.Citation56 Unlike almost all other second-line agents for sarcoidosis which typical require several months to reach maximum efficacy, infliximab often shows a therapeutic response within a few weeks.Citation31

Despite the promising results of infliximab for the treatment of sarcoidosis, its expense and the fact that it requires regular intravenous infusions prevent the drug from being the drug of choice for most forms of sarcoidosis. We would position infliximab as a third-line agent after corticosteroids plus a corticosteroid sparing agent have failed to provide an adequate treatment response. As the limited data suggest, the drug is very effective for sarcoidosis, it could be considered in cases of severe sarcoidosis as a second line agent or given initially with corticosteroids in that situation. As mentioned, infliximab could be considered as a second line for the treatment of lupus pernio or neurosarcoidosis as the limited data suggest that it may be particularly effective for those forms of sarcoidosis.

The typical dosing of infliximab for sarcoidosis is 3–5 mg/kg with loading doses at weeks 0, 2, 6, and then every 6 weeks thereafter.Citation31 The maintenance dosing interval may then be adjusted according to the patient’s response. As most of the patients who receive infliximab have a history of chronic, recalcitrant severe disease, most patients will relapse if the drug is discontinued.Citation67 Therefore, infliximab therapy usually needs to be continued unless the patient is converted to another anti-sarcoidosis agent.

The side effects of infliximab include allergic reactions. Infliximab is a chimeric antibody with a murine-derived portion that is often the source of these allergic reactions. Although these reactions are rarely life threatening, the drug must be permanently discontinued if such reactions occur. These allergic reactions are often related to antibody formation against the murine portion of infliximab. Such antibody formation may also diminish the drug’s efficacy. To prevent such antibody formation, some have advocated routinely using concomitant immunosuppressive medications (eg, low-dose methotrexate) whenever infliximab is used. Additional infliximab side effects include leukopenia and immunosuppression. In particular, latent tuberculosis infection can be reactivated by use of infliximab that may be life threatening.Citation68 Therefore, all patients receiving the drug must be screened for tuberculosis with a tuberculin skin test or blood interferon release assay. Evidence of infliximab worsening congestive heart failure has prohibited the use of the drug with New York Heart Association Class 3 and 4 heart failure. Although controversial,Citation69 the drug appears to be associated with an increased risk of malignancy, especially lymphoma.Citation70 Neurologic complications including demyelination syndromes may rarely occur with infliximab.Citation71

Other TNF-α antagonist biologicals have been used to treat sarcoidosis, with mixed results. Adalimumab appears to be useful for the treatment of sarcoidosis. It has advantages over infliximab is that it is a fully humanized antibody so that allergic reactions may be less frequent. Also, because adalimumab in given subcutaneously instead of intravenously, it is less cumbersome to use. Although medical evidence is limited, adalimumab often requires a relatively high dose (eg, 40 mg subcutaneously every week)Citation72 and a relatively long time period compared to infliximab to reach maximum efficacy. Etanercept appears not to be particularly useful for the treatment of sarcoidosis.Citation73,Citation74 Although all TNF-α antagonists may rarely induce exacerbations of sarcoidosis, this most commonly occurs with etanercept.Citation75–Citation78 It has been postulated that TNF-α antagonist-induced sarcoidosis may occur via stimulation of IFN-γ production leading to the development of granulomatous inflammation.Citation75 Oral TNF-α antagonist drugs such as thalidomide and apremilast may have some activity in sarcoidosis, although they do not appear to be very potent for this condition.Citation59,Citation79,Citation80

Other drugs

Numerous other drugs have been reported to be effective for sarcoidosis in case reports and small case series. These include rituximab,Citation81,Citation82 tetracyclines (especially for skin sarcoidosis),Citation83 and cyclosporine (although the drug was found not to be effective in a randomized trial for pulmonary sarcoidosis,Citation84 it may be beneficial for neurosarcoidosisCitation85).

, adapted from a previously published paper,Citation86 lists the drug recommendations for various forms of sarcoidosis. shows general drug dosing recommendations for sarcoidosis.

Table 1 Drugs for the treatment of sarcoidosis

Table 2 Drug dosing of treatment of sarcoidosis

Potential therapies for sarcoidosis

Ideally, pharmacotherapy for sarcoidosis should be based on a complete understanding of disease immunopathogenesis, with compounds developed that target specific portions of relevant inflammatory pathways. Unfortunately, the immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis is not completely understood.

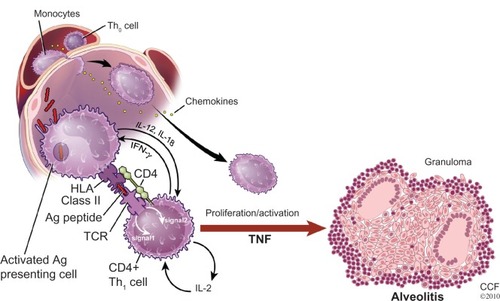

shows the proposed general schema leading to the development of the sarcoid granuloma. It is thought the process starts with the presentation of an antigen to an antigen-presenting cell (APC). The antigen is then processed by the APC and presented to a T-cell receptor by means of a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecule. The T-cells involved are usually of the CD+4 class. Such binding involves the secretion of numerous cytokines from various cells as well as the formation of additional bridging molecules, only a handful of which are depicted in . These cytokines and bridging molecules cause polarization of T-cells to a T-helper-1 (Th1) phenotype, T-cell proliferation, recruitment of monocytes that are differentiated into macrophages leading to the formation of the sarcoid granuloma.Citation34

Figure 4 A proposed basic scenario for the immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis.

Reprinted with permission from Baughman RP, Culver DA, Judson MA. A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(5):573–581.Citation34

Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2013 American Thoracic Society.

Abbreviations: CCF, Cleveland Clinic Foundation; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; IL, interleukin; TCR, T cell receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Most pharmacotherapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis has not targeted specific portions of this inflammatory process. Corticosteroids inhibit the expression of many inflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-11, IL-12, IL-19, IFN-γ, and TNF-α.Citation87 Corticosteroids also inhibit aracidonic acid metabolism, downregulate T-cell immunity, diminish T-cell activation, and enhance apoptosis of activated T-cells.Citation87,Citation88 The mechanisms relevant to suppression of the granulomtous inflammation in sarcoidosis may involve all of these effects.Citation87 Many other anti-sarcoidosis therapies such as methotrexate, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide affect DNA and RNA production, and therefore, nonspecifically inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and function.

TNF-α antagonists represent a specific therapy targeted against an important building block of the sarcoid granuloma. Future therapies may target other specific inflammatory mediators involved in granuloma formation. Other potential therapies could be directed against the formation of the (APC)–(HLA molecule)–(processed antigen)–(T-cell receptor)–(T-cell) structure (). This could be achieved by competitive inhibitors or by blocking molecules. This structure is thought to be required in order for T-cell activation, proliferation, and monocyte recruitment to occur, resulting in the sarcoid granuloma. Disruption of T-cell signaling may also disturb this model and would be a promising therapy for sarcoidosis. Finally, recent data suggest that sarcoidosis may be the result of continuous exposure of antigen to the immune system resulting in T-cell exhaustion. This may be precipitated by the presence of an amyloid substance that not only presents the sarcoid antigen but prevents it from being cleared via normal immune clearance mechanisms.Citation89 Perhaps an “anti-amyloid therapy” would result in degradation of the sarcoid antigen such that granulomatous inflammation would cease. As Toll-like receptor 2 may be involved with this amyloid formation,Citation89 drugs directed against this inflammatory molecule may be beneficial.

Conclusion

The treatment of sarcoidosis is not standardized. It is primarily driven by the effect of sarcoidosis upon the patient’s symptoms and quality of life. In a large percentage of sarcoidosis patients, treatment is not indicated. Corticosteroids are the drug of choice for most forms of sarcoidosis. When corticosteroids are required chronically, corticosteroid sparing agents should be strongly considered.

Disclosure

Drs Beegle, Barba, and Gobunsuy have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr Judson is a consultant for Janssen and Celgene.

References

- Hunninghake GW Costabel U Ando M ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999 16 2 149 173 10560120

- Judson MA An approach to the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis with corticosteroids: the six phases of treatment Chest 1999 115 4 1158 1165 10208222

- Judson MA The treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis Respir Med 2012 106 10 1351 1361 22495110

- Ohara K Judson MA Baughman RP Clinical aspects of ocular sarcoidosis Eur Respir Mon 2005 10 188 209

- Rosen Y Pathology of sarcoidosis Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2007 28 1 36 52 17330191

- Bell NH Stern PH Pantzer E Sinha TK DeLuca HF Evidence that increased circulating 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D is the probable cause for abnormal calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis J Clin Invest 1979 64 1 218 225 312811

- Burke RR Rybicki BA Rao DS Calcium and vitamin D in sarcoidosis: how to assess and manage Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010 31 4 474 484 20665397

- Sharma OP Renal sarcoidosis and hypercalcemia Eur Respir Mon 2005 32 220 232

- Smedema JP Snoep G van Kroonenburgh MP Cardiac involvement in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis assessed at two university medical centers in The Netherlands Chest 2005 128 1 30 35 16002912

- Judson MA Gilbert GE Rodgers JK Greer CF Schabel SI The utility of the chest radiograph in diagnosing exacerbations of pulmonary sarcoidosis Respirology 2008 13 1 97 102 18197917

- Iannuzzi MC Rybicki BA Teirstein AS Sarcoidosis N Engl J Med 2007 357 21 2153 2165 18032765

- Grutters JC van den Bosch JM Corticosteroid treatment in sarcoidosis Eur Respir J 2006 28 3 627 636 16946094

- Schutt AC Bullington WM Judson MA Pharmacotherapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a Delphi consensus study Respir Med 2010 104 5 717 723 20089389

- Baughman RP Iannuzzi MC Lower EE Use of fluticasone in acute symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2002 19 3 198 204 12405489

- Pietinalho A Tukiainen P Haahtela T Persson T Selroos O Early treatment of stage II sarcoidosis improves 5-year pulmonary function Chest 2002 121 1 24 31 11796428

- Gottlieb JE Israel HL Steiner RM Triolo J Patrick H Outcome in sarcoidosis. The relationship of relapse to corticosteroid therapy Chest 1997 111 3 623 631 9118698

- Eule H Weinecke A Roth I Wuthe H The possible influence of corticosteroid therapy on the natural course of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Late results of a continuing clinical study Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986 465 695 701 3524366

- Izumi T Sarcoidosis in Kyoto (1963–1986) Sarcoidosis 1988 5 2 142 146 3227188

- Rodrigues SC Rocha NA Lima MS Factor analysis of sarcoidosis phenotypes at two referral centers in Brazil Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2011 28 1 34 43 21796889

- Paramothayan NS Lasserson TJ Jones PW Corticosteroids for pulmonary sarcoidosis Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005 2 CD001114 15846612

- Baughman RP Lower EE Kaufman AH Ocular sarcoidosis Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010 31 4 452 462 20665395

- Nunes H Freynet O Naggara N Cardiac sarcoidosis Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010 31 4 428 441 20665393

- Yazaki Y Isobe M Hiroe M Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone Am J Cardiol 2001 88 9 1006 1010 11703997

- Hamzeh NY Wamboldt FS Weinberger HD Management of cardiac sarcoidosis in the United States: a Delphi study Chest 2012 141 1 154 162 21737493

- Lower EE Broderick JP Brott TG Baughman RP Diagnosis and management of neurological sarcoidosis Arch Intern Med 1997 157 16 1864 1868 9290546

- Zajicek JP Scolding NJ Foster O Central nervous system sarcoidosis – diagnosis and management QJM 1999 92 2 103 117 10209662

- Sharma OP Neurosarcoidosis: a personal perspective based on the study of 37 patients Chest 1997 112 1 220 228 9228380

- Marchell RM Judson MA Cutaneous sarcoidosis Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010 31 4 442 451 20665394

- Haimovic A Sanchez M Judson MA Prystowsky S Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. Cutaneous disease J Am Acad Dermatol 2012 66 5 699 e691 e618 quiz 717–698 22507585

- Lazar CA Culver DA Treatment of sarcoidosis Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010 31 4 501 518 20665400

- Baughman RP Drent M Kavuru M Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement Am J Respir Critl Care Med 2006 174 7 795 802

- Lower EE Baughman RP Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis Arch Intern Med 1995 155 8 846 851 7717793

- Baughman RP Costabel U du Bois RM Treatment of sarcoidosis Clin Chest Med 2008 29 3 533 548 ix x 18539243

- Baughman RP Culver DA Judson MA A concise review of pulmonary sarcoidosis Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011 183 5 573 581 21037016

- Morgan SL Baggott JE Vaughn WH Supplementation with folic acid during methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Ann Intern Med 1994 121 11 833 841 7978695

- Kalia S Dutz JP New concepts in antimalarial use and mode of action in dermatology Dermatol Ther 2007 20 4 160 174 17970883

- Baltzan M Mehta S Kirkham TH Cosio MG Randomized trial of prolonged chloroquine therapy in advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis Am Journal Respir Crit Care Med 1999 160 1 192 197 10390399

- Jones E Callen JP Hydroxychloroquine is effective therapy for control of cutaneous sarcoidal granulomas J Am Acad Dermatol 1990 23 3 Pt 1 487 489 2212149

- Adams JS Diz MM Sharma OP Effective reduction in the serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and calcium concentration in sarcoidosis-associated hypercalcemia with short-course chloroquine therapy Ann Internal Med 1989 111 5 437 438 2764407

- Barre PE Gascon-Barre M Meakins JL Goltzman D Hydroxychloroquine treatment of hypercalcemia in a patient with sarcoidosis undergoing hemodialysis Am J Med 1987 82 6 1259 1262 3605143

- O’Leary TJ Jones G Yip A Lohnes D Cohanim M Yendt ER The effects of chloroquine on serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis N Engl J Med 1986 315 12 727 730 3755800

- Sweiss NJ Patterson K Sawaqed R Rheumatologic manifestations of sarcoidosis Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2010 31 4 463 473 20665396

- Baughman RP Lower EE Steroid-sparing alternative treatments for sarcoidosis Clin Chest Med 1997 18 4 853 864 9413663

- Ruckemann K Fairbanks LD Carrey EA Leflunomide inhibits pyrimidine de novo synthesis in mitogen-stimulated T-lymphocytes from healthy humans J Biol Chem 1998 273 34 21682 21691 9705303

- Sahoo DH Bandyopadhyay D Xu M Effectiveness and safety of leflunomide for pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis Eur Respir J 2011 38 5 1145 1150 21565914

- Baughman RP Lower EE Leflunomide for chronic sarcoidosis Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2004 21 1 43 48 15127974

- Smolen JS Emery P Kalden JR The efficacy of leflunomide monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis: towards the goals of disease modifying antirheumatic drug therapy J Rheumatol Suppl 2004 71 13 20 15170903

- Emery P Breedveld FC Lemmel EM A comparison of the efficacy and safety of leflunomide and methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000 39 6 655 665 10888712

- van Riel PL Smolen JS Emery P Leflunomide: a manageable safety profile J Rheumatol Suppl 2004 71 21 24 15170904

- Androdias G Maillet D Marignier R Mycophenolate mofetil may be effective in CNS sarcoidosis but not in sarcoid myopathy Neurology 2011 76 13 1168 1172 21444902

- Kouba DJ Mimouni D Rencic A Nousari HC Mycophenolate mofetil may serve as a steroid-sparing agent for sarcoidosis Br J Dermatol 2003 148 1 147 148 12534610

- Bhat P Cervantes-Castaneda RA Doctor PP Anzaar F Foster CS Mycophenolate mofetil therapy for sarcoidosis-associated uveitis Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2009 17 3 185 190 19585361

- Doty JD Mazur JE Judson MA Treatment of corticosteroid-resistant neurosarcoidosis with a short-course cyclophosphamide regimen Chest 2003 124 5 2023 2026 14605084

- Chapelon-Abric C de Zuttere D Duhaut P Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases Medicine 2004 83 6 315 334 15525844

- Demeter SL Myocardial sarcoidosis unresponsive to steroids. Treatment with cyclophosphamide Chest 1988 94 1 202 203 3383636

- Sodhi M Pearson K White ES Culver DA Infliximab therapy rescues cyclophosphamide failure in severe central nervous system sarcoidosis Respir Med 2009 103 2 268 273 18835147

- Haubitz M Schellong S Gobel U Intravenous pulse administration of cyclophosphamide versus daily oral treatment in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and renal involvement: a prospective, randomized study Arthritis Rheum 1998 41 10 1835 1844 9778225

- Somers EC Marder W Christman GM Ognenovski V McCune WJ Use of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for protection against premature ovarian failure during cyclophosphamide therapy in women with severe lupus Arthritis Rheum 2005 52 9 2761 2767 16142702

- Judson MA Silvestri J Hartung C Byars T Cox CE The effect of thalidomide on corticosteroid-dependent pulmonary sarcoidosis Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2006 23 1 51 57 16933470

- Zabel P Entzian P Dalhoff K Schlaak M Pentoxifylline in treatment of sarcoidosis Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997 155 5 1665 1669 9154873

- Doty JD Mazur JE Judson MA Treatment of sarcoidosis with infliximab Chest 2005 127 3 1064 1071 15764796

- Baughman RP Lower EE Infliximab for refractory sarcoidosis Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2001 18 1 70 74 11354550

- Fehrenbach H Zissel G Goldmann T Alveolar macrophages are the main source for tumour necrosis factor-alpha in patients with sarcoidosis Eur Respir J 2003 21 3 421 428 12661995

- Zissel G Muller-Quernheim J Sarcoidosis: historical perspective and immunopathogenesis (Part I) Respir Med 1998 92 2 126 139 9616502

- Judson MA Baughman RP Costabel U Efficacy of infliximab in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: results from a randomised trial Eur Respir J 2008 31 6 1189 1196 18256069

- Stagaki E Mountford WK Lackland DT Judson MA The treatment of lupus pernio: results of 116 treatment courses in 54 patients Chest 2009 135 2 468 476 18812454

- Panselinas E Rodgers JK Judson MA Clinical outcomes in sarcoidosis after cessation of infliximab treatment Respirology 2009 14 4 522 528 19386069

- Keane J Gershon S Wise RP Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent N Engl J Med 2001 345 15 1098 1104 11596589

- Lopez-Olivo MA Tayar JH Martinez-Lopez JA Risk of malignancies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologic therapy: a meta-analysis JAMA 2012 308 9 898 908 22948700

- Cush JJ Dao KH Malignancy risks with biologic therapies Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2012 38 4 761 770 23137581

- Nozaki K Silver RM Stickler DE Neurological deficits during treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists Am J Med Sci 2011 342 5 352 355 21876428

- Erckens RJ Mostard RL Wijnen PA Schouten JS Drent M Adalimumab successful in sarcoidosis patients with refractory chronic non-infectious uveitis Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2012 250 5 713 720 22119879

- Baughman RP Lower EE Bradley DA Raymond LA Kaufman A Etanercept for refractory ocular sarcoidosis: results of a double-blind randomized trial Chest 2005 128 2 1062 1047 16100213

- Utz JP Limper AH Kalra S Etanercept for the treatment of stage II and III progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis Chest 2003 124 1 177 185 12853521

- Louie GH Chitkara P Ward MM Relapse of sarcoidosis upon treatment with etanercept Ann Rheum Dis 2008 67 6 896 898 18474661

- van der Stoep D Braunstahl GJ van Zeben J Wouters J Sarcoidosis during anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy: no relapse after rechallenge J Rheumatol 2009 36 12 2847 2848 19966199

- Verschueren K Van Essche E Verschueren P Taelman V Westhovens R Development of sarcoidosis in etanercept-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients Clin Rheumatol 2007 26 11 1969 1971 17340045

- Burns AM Green PJ Pasternak S Etanercept-induced cutaneous and pulmonary sarcoid-like granulomas resolving with adalimumab J Cutan Pathol 2012 39 2 289 293 21899592

- Baughman RP Judson MA Teirstein AS Moller DR Lower EE Thalidomide for chronic sarcoidosis Chest 2002 122 1 227 232 12114363

- Baughman RP Judson MA Ingledue R Craft NL Lower EE Efficacy and safety of apremilast in chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis Arch Dermatol 2012 148 2 262 264 22004880

- Lower EE Baughman RP Kaufman AH Rituximab for refractory granulomatous eye disease Clin Ophthalmol 2012 6 1613 1618 23055686

- Bomprezzi R Pati S Chansakul C Vollmer T A case of neurosarcoidosis successfully treated with rituximab Neurology 2010 75 6 568 570 20697110

- Bachelez H Senet P Cadranel J Kaoukhov A Dubertret L The use of tetracyclines for the treatment of sarcoidosis Arch Dermatol 2001 137 1 69 73 11176663

- Wyser CP van Schalkwyk EM Alheit B Bardin PG Joubert JR Treatment of progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis with cyclosporin A. A randomized controlled trial Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997 156 5 1371 1376 9372647

- Stern BJ Schonfeld SA Sewell C Krumholz A Scott P Belendiuk G The treatment of neurosarcoidosis with cyclosporine Arch Neurol 1992 49 10 1065 1072 1329698

- Judson MA The management of sarcoidosis by the primary care physician Am J Med 2007 120 5 403 407 17466647

- Petrache I Moller DR Mechanism of therapy for sarcoidosis Baughman RP Sarcoidosis New York, NY Taylor and Francis Group 2006 210 671 687

- Khalil N Whitman C Zuo L Danielpour D Greenberg A Regulation of alveolar macrophage transforming growth factor-beta secretion by corticosteroids in bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation in the rat J Clinical Invest 1993 92 4 1812 1818 7691887

- Chen ES Song Z Willett MH Serum amyloid A regulates granulomatous inflammation in sarcoidosis through Toll-like receptor-2 Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010 181 4 360 373 19910611