Abstract

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is increasingly applied in adults with acute refractory respiratory failure that is deemed reversible. Bleeding is the most frequent complication during ECMO support. Severe pre-existing bleeding has been considered a contraindication to ECMO application. Nevertheless, there are cases of successful ECMO application in patients with multiple trauma and hemorrhagic shock or head trauma and intracranial hemorrhage. ECMO has proved to be life-saving in several cases of life-threatening respiratory failure associated with pulmonary hemorrhage of various causes, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s disease). We successfully applied ECMO in a 65-year-old woman with acute life-threatening respiratory failure due to diffuse massive pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis, manifested as severe pulmonary-renal syndrome. ECMO sustained life and allowed disease control, together with plasmapheresis, cyclophosphamide, corticoids, and renal replacement therapy. The patient was successfully weaned from ECMO, extubated, and discharged home. She remains alive on dialysis at 17 months follow-up.

Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is used to preserve life in acute (de novo or decompensation of chronic) cardiac and/or respiratory failure, when optimal conventional therapy fails. Offering temporary support, veno-arterial ECMO is used in cardiac or cardiorespiratory failure, while veno-venous (VV) ECMO is used in respiratory failure without cardiac compromise. Respiratory ECMO is almost uniformly used as a bridge to recovery, thus it is indicated only when the respiratory failure is deemed reversible, while treatment of the underlying disease is essential.Citation1–Citation11

According to the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO)Citation12 General Guidelines, ECMO treatment is considered when the expected mortality with conventional treatment is higher than 50% and is usually indicated when it is higher than 80%.

According to the 2004 ELSO Registry Report,Citation1 ECMO had been mainly applied for neonatal respiratory failure (with 77% survival to discharge or transfer), while the adult respiratory group was the smallest group treated with ECMO, having a survival to discharge of 53%. After the encouraging results of the randomized CESAR (Conventional ventilation or ECMO for Severe Adult Respiratory failure) trialCitation2 and the ECMO treatment for acute respiratory failure associated with the influenza A H1N1 viral infection, ECMO application for adult respiratory failure has been tremendously increased.Citation9 According to the ELSOCitation12 International Summary (January 2013), the adult respiratory ECMO cases outnumber the adult cardiac cases and have a survival to discharge or transfer of 55%. In our hospital the ratio of adult respiratory versus adult cardiac cases is 10:1.

Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG), renamed “granulomatosis with polyangiitis” (GPA), is an antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, characterized by multifocal vascular necrotizing inflammation and granulomas. Genetic and microbial factors may play a role in induction and expression of the autoimmune process. GPA is a multisystem disease that can affect any organ/system, having a variable clinical presentation. Nevertheless, it is most frequently manifested as small vessel vasculitis affecting the upper and lower respiratory tract and the kidneys. In ANCA-associated vasculitis, including GPA, alveolar hemorrhage, and concomitant glomerulonephritis causing renal insufficiency (pulmonary-renal syndrome) are associated with high mortality.Citation5,Citation7–Citation11,Citation13–Citation22

Case report

A 65-year-old woman was transferred from an associated hospital (after 2 days of hospitalization) with acute renal and respiratory failure after repeated episodes of hemoptysis.

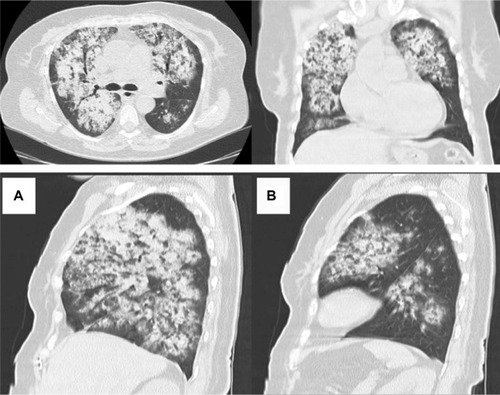

She had been treated for chronic sinusitis the year before, had history of gross hematuria for 16 days, and repeated hemoptysis the 2 days before admission to our hospital. Lesions characteristic of GPA were found on nasal endoscopy, fresh blood originating from all segmental orifices was revealed on two bronchoscopies. Massive bilateral pulmonary opacities, consolidations attributed to alveolar infiltrations, and a few small cavitary lesions were revealed on computed tomography, which were performed at the referring hospital (, and ). Therefore the first prednisolone pulse of 500 mg intravenous (IV) was given in the referring hospital.

Figure 1 Chest computed tomography on admission showing bilateral opacities attributed to alveolar infiltrations as well as a few small cavitary lesions. (A) left lung, (B) right lung.

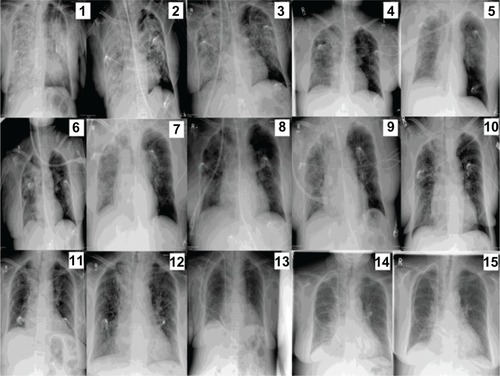

Figure 2 Sequential dates of radiographic presentation.

The gross hematuria was followed by severe oliguria and periods of anuria. Numerous erythrocytes containing approximately 20% acanthocytes were revealed in the urinary sediment, as well as red blood cell casts. The creatinine rapidly increased in the 48 hours after the first episode of hemoptysis, being 5.9 mg/dL on admission to our hospital. The diagnosis of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis was made based on clinical observations.

Her respiratory function continued to deteriorate. She became progressively dyspneic, and after the first night on referral, became tachypneic. Furthermore, she was severely desaturated (PaO2 49 mmHg), and was fitted with a face mask with 10 liters of oxygen per minute. She had up to 30 episodes of hemoptysis daily for 3 consecutive days. She was semi-electively intubated the day after her admission.

The first 3 hours after intubation, 200 mL/hour of blood was suctioned from the endotracheal tube. On repeated bronchoscopies, there was continued massive diffuse bleeding, originating from all segmental orifices (more prominent on the right side). The ventilator settings had to be elevated (biphasic positive airway pressure) from 28/10 cm H2O to 35/15 cm H2O, with steadily reduced inspiratory to expiratory ratio, resulting in ratios near to 1:1. Fractional inspired oxygen was increased from 60% to 100%, but hypoxemia persisted (PaO2 52.4 mmHg before ECMO initiation). Continued hemoptysis resulted not only in reduced alveolar diffusion capacity but also in repeated airway obstruction. Despite severe respiratory compromise, she remained hemodynamically stable, with good ventricular function on echocardiography, and without requirement of inotropes and/or vasoconstrictors. Twelve hours after intubation, her Horowitz-index was 50, and a VV-ECMO by the Cardiohelp System of Maquet (MAQUET Cardiopulmonary AG, Hirrlingen, Germany), including the HLS Set Advanced 5.0 (MAQUET Cardiopulmonary AG, Hirrlingen, Germany) for application of a maximal flow of 5 L/minute, was semi-electively inserted percutaneously, with inflow cannula to right femoral vein (21 catheter) and outflow cannula to the right internal jugular vein (19 catheter). The ECMO flow was initially set to 4 L/minute, biphasic positive airway pressure and fractional inspired oxygen levels were drastically decreased, while blood gases were dramatically improved (). Because of high ANCA levels (proteinase 3-ANCA 150 U/mL; normal lab range <4 U/mL), the presence of acanthocytosis with red blood cell casts, together with acute renal failure and diffuse hemorrhagic alveolar infiltrates, the diagnosis of GPA presenting as pulmonary-renal syndrome was made. Additionally, both anti-double-stranded DNA antibodies and anti-glomerular-basement antibodies were negative, making both lupus erythematodes and Goodpasture’s syndrome improbable.

Table 1 Patient parameters

Immunosuppression with prednisolone (500 mg IV daily) that had been started at the referring hospital was continued and supported by plasmapheresis to reduce the level of ANCA-autoantibodies after inserting a Shaldon catheter into the left jugular vein 9 hours before ECMO initiation. Because of anuria and fluid overload, continuous VV hemofiltration through the Shaldon catheter was started during the first 24 hours of ECMO support in order to replace the missing kidney function. As cyclophosphamide is removed by hemofiltration pulse, cyclophosphamide was delayed until day 2, following the second plasmapheresis and the second hemofiltration.

To reduce the risk of bleeding, citrate was used as anticoagulation regimen for plasmapheresis, which enabled an intracorporeal activated clotting time (ACT) of 160–200, without changes in systemic coagulation. For the same reasons, citrate hemofiltration with neutralization of systemic citrate by calcium perfusion was used for the first and second hemofiltration. Later, heparin was used for the following two hemofiltrations, but due to suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia type II, argatroban was adapted thereafter with a targeted ACT range between 160–200. The length of hemofiltration was limited to approximately 5 to 6 hours to reduce the risk of bleeding. No anticoagulation was administered during ECMO, except the registered ACT fluctuated between 160–200 and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) between 41–66 seconds. The platelet count fluctuated between 38,000–245,000 uL. Platelets were transfused with counts decreasing below 50,000 uL during ECMO ().

Table 2 Citrate hemofiltration was started to reduce the risk of systemic anticoagulation

Hemoptysis progressively decreased and stopped 6 days after ECMO initiation. Clinical, radiological, bronchoscopical, and laboratory findings showed progressive improvement that allowed ECMO weaning and discontinuation after 10 days of support, and extubation on the following day, after 11 days of mechanical ventilation. The weaning process is described in ().

Continuous VV hemofiltration was continued daily for 20 days, and replaced by hemodialysis three times a week due to terminal renal failure. Plasmapheresis was performed daily for 15 days (with administration of 31 units of fresh frozen plasma) and continued every second day for 21 more days (with administration of human albumin 4.2%), effectively reducing the proteinase 3 titers.

The patient made a remarkable recovery, maintained good respiratory function, and was discharged home after 46 days of hospitalization and chronic dialysis.

Pulse cyclophosphamide was administered for a total of 3 months, up to a total dose of 4.73 gm, followed by azathioprine (100 mg orally, daily) and prednisolone (tapered to 5 mg orally daily). At 17 month follow-up, she had no relapses maintaining good respiratory function.

Discussion

ECMO requires systemic anticoagulation with continuous heparin infusion to maintain an ACT of about 1.5 times that of normal. Bleeding is the most common complication during ECMO support, attributed to anticoagulation and thrombocytopathia that are accelerated by the oxygenator-related blood trauma. The risk of systemic bleeding with anticoagulation is a relative contraindication to ECMO.Citation3,Citation5,Citation9,Citation11,Citation12,Citation23 Furthermore, preexisting severe bleeding has been considered a contraindication.Citation5,Citation9,Citation24,Citation25 Nevertheless, good results have been reported in ECMO recipients with severe respiratory failure associated with trauma and hemorrhagic shock,Citation24 intracranial bleeding,Citation25 and severe pulmonary bleeding of various causes.Citation4–Citation11,Citation17–Citation22

In 1994, Siden et al reported ECMO application in four cases of acute, severe pulmonary hemorrhage in infancy.Citation26 Kolovos et al,Citation4 in 2002, reported 100% survival with VV or vino-arterial ECMO in a case series of nine children with severe acute respiratory failure caused by pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to sepsis or autoimmune diseases including GPA. Reviewing the ELSO database they reported 72% and 67% survival among 18 neonates and three children, respectively, who received ECMO for the treatment of pulmonary hemorrhage. Subsequently, ECMO has been successfully applied to children with severe respiratory failure due to pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis,Citation27 fulminant Wilson disease,Citation28 nodose polyarteritis,Citation29 Goodpasture’s syndrome,Citation6 and ANCA-related vasculitis, including severe microscopic polyangiitis,Citation5,Citation8 and GPA.Citation7,Citation9

ECMO has been successfully applied to adults with respiratory failure due to pulmonary hemorrhage attributed to various causes, including autoimmune vasculitis. There are case reports of successful ECMO application to adults with refractory life-threatening respiratory failure due to warfarin-exacerbated diffuse alveolar hemorrhage,Citation30 massive pulmonary hemorrhage after lobar lung transplantation,Citation31 massive lung bleeding with airway blood clot obstruction after pulmonary endarterectomy,Citation32,Citation33 pulmonary hemorrhage related with right middle lobe bronchiectasis,Citation34 and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage after silicone embolism.Citation35

There are several case reports of ECMO application in adult patients with refractory acute respiratory failure associated with severe pulmonary bleeding secondary to autoimmune vasculitis, including ANCA-associated vasculitis. Initial improvement and weaning from ECMO has been reported in an adult patient with Goodpasture’s-like pulmonary-renal syndrome, who subsequently died after rebleeding.Citation36 There are at least seven case reports of VV ECMO applied to adults with acute refractory respiratory failure secondary to Wegener’s granulomatosis, most of which had severe preexisting pulmonary hemorrhage.Citation11,Citation18–Citation22,Citation37

Measures to normalize the coagulation status applied in ECMO recipients treated for pulmonary bleeding include reduced heparin administration, transfusions of platelets, fresh frozen plasma, and specific clotting factors according to deficiencies, and administration of ε-aminocaproic acid in fibrinolysis.Citation3,Citation5,Citation9,Citation12,Citation23 Nafamostat mesylate as anticoagulant is also rarely reported.Citation31,Citation36 Heparin infusion to maintain an ACT of 160–180Citation4,Citation5 or 130–150 seconds (instead of the institutional standard of 180–220) and a modified ECMO circuit with two oxygenators placed in parallel (one primed in-line to allow quick change in case of clotting)Citation9 have been reported in pediatric patients with pulmonary hemorrhage due to GPA.

Thrombo-resistant coated circuits (heparin-bonded, nitric oxide-treated)Citation4 may allow withholding heparin for a period of time with less risk of clotting, particularly if flow is kept high. Initially, heparin-free or prolonged heparin-free ECMO has been applied in multiple trauma and intracranial bleeding patients, respectively.Citation24,Citation25 Heparin administration after the first 48 hours,Citation11,Citation21 initial heparin anticoagulation, and later conversion to lepirudin after complication by heparin induced thrombocytopeniaCitation20 have been reported in adult patients with pulmonary hemorrhage due to GPA.

ECMO proved life-saving in our patient. It maintained oxygenation necessary due to massive pulmonary hemorrhage obstruction and alveolar diffusion problems with less ventilator induced trauma, and it supported the patient until resolution of her respiratory failure, providing time for treatment and control of the underlying disease by plasmapheresis and immunosuppression. Thrombo-resistant circuits were used, and regional anticoagulation was administered to plasmapheresis. Systemic anticoagulation for hemofiltration was reduced to a minimum by either using citrate hemofiltration or by time restriction using heparin or argatroban with ranges of ACT between 160–200 and aPTT between 41–66 seconds. Pulmonary bleeding stopped completely within 6 days of ECMO support. There was minor extrapulmonary bleeding (eg, nose, insertion points of catheters) until day 8 after ECMO initiation and no clotting complications.

ECMO application in adult respiratory failure has been questioned;Citation38 nevertheless, it is gaining an increasing role,Citation39 and most contraindications to its use are becoming weaker. Respiratory ECMO is applied as a rescue therapy offering respiratory support to maintain life, as a bridge to recovery in reducing the ventilator-induced lung injury (oxygen toxicity and barotrauma) and allowing pulmonary rest,Citation4,Citation9 as a supportive therapy providing time for diagnosis and treatment of the underlying causative disease until its control or resolution, and rarely as a bridge to lung transplantation.Citation40,Citation41 ECMO treatment in respiratory failure associated with severe pulmonary bleeding imposes a management dilemma. Although limited, the reported experience of successful ECMO application in acute respiratory failure associated with pulmonary bleeding continues to accumulate,Citation4–Citation11,Citation17–Citation22,Citation26–Citation37 thus encouraging consideration of its application.Citation39

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Conrad SA Rycus PT Dalton H Extracorporeal life support registry report 2004 ASAIO J 2005 51 1 4 10 15745126

- Peek GJ Mugford M Tiruvoipati R CESAR trial collaboration Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial Lancet 2009 374 9698 1351 1363 19762075

- Pitsis AA Visouli AN Mechanical assistance of the circulation during cardiogenic shock Curr Opin Crit Care 2011 17 5 425 438 21897218

- Kolovos NS Schuerer DJ Moler FW Extracorporeal life support for pulmonary hemorrhage in children: a case series Crit Care Med 2002 30 3 577 580 11990918

- Agarwal HS Taylor MB Grzeszczak MJ Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and plasmapheresis for pulmonary hemorrhage in microscopic polyangiitis Pediatr Nephrol 2005 20 4 526 528 15714314

- Dalabih A Pietsch J Jabs K Hardison D Bridges BC Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a platform for recovery: a case report of a child with pulmonary hemorrhage, refractory hypoxemic respiratory failure, and new onset goodpasture syndrome J Extra Corpor Technol 2012 44 2 75 77 22893987

- Hernandez ME Lovrekovic G Schears G Acute onset of Wegener’s granulomatosis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage treated successfully by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation Pediatr Crit Care Med 2002 3 1 63 66 12793925

- Di Maria MV Hollister R Kaufman J Case report: severe microscopic polyangiitis successfully treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and immunosuppression in a pediatric patient Curr Opin Pediatr 2008 20 6 740 742 19005344

- Joseph M Charles AG Early extracorporeal life support as rescue for Wegener granulomatosis with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a case report and literature review Pediatr Emerg Care 2011 27 12 1163 1166 22158275

- Guo Z Li X Jiang LY Xu LF Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the management of respiratory failure caused by diffuse alveolar hemorrhage J Extra Corpor Technol 2009 41 1 37 40 19361031

- Ahmed SH Aziz T Cochran J Highland K Use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a patient with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage Chest 2004 126 1 305 309 15249477

- Extracorporeal Life Support Organization ELSO Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Extracorporeal Life Support Ann Arbor, MI 2009 Available from: http://www.elso.med.umich.edu/WordForms/ELSO%20Guidelines%20General%20All%20ECLS%20Version1.1.pdf

- Falk RJ Gross WL Guillevin L Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s): an alternative name for Wegener’s granulomatosis Arthritis Rheum 2011 63 4 863 864 21374588

- Jennette JC Nomenclature and classification of vasculitis: lessons learned from granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis) Clin Exp Immunol 2011 164 Suppl 1 7 10 21447122

- Chung SA Xie G Roshandel D Meta-analysis of genetic polymorphisms in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) reveals shared susceptibility loci with rheumatoid arthritis Arthritis Rheum 2012 64 10 3463 3471 22508400

- Kallenberg CG Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitides Ann Rheum Dis 2011 70 Suppl 1 i59 i63 21339221

- Matsumoto T Ueki K Tamura S Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for the management of respiratory failure due to ANCA-associated vasculitis Scand J Rheumatol 2000 29 3 195 197 10898076

- Hartman A Nordal K Svennevig J Successful use of artificial lung (ECMO) and kidney in the treatment of a 20 year-old female with Wegener’s syndrome Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994 9 3 316 319 8052441

- Rosengarten A Elmore P Epstein J Long distance road transport of a patient with Wegener’s Granulomatosis and respiratory failure using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2002 14 2 181 187 12147115

- Balasubramanian SK Tiruvoipati R Chatterjee S Sosnowski A Firmin RK Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with lepirudin anticoagulation for Wegener’s granulomatosis with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia ASAIO J 2005 51 4 477 479 16156317

- Gay SE Ankney N Cochran JB Highland KB Critical care challenges in the adult ECMO patient Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2005 24 4 157 162 quiz 163–164 16043975

- Barnes SL Naughton M Douglass J Murphy D Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with plasma exchange in a patient with alveolar haemorrhage secondary to Wegener’s granulomatosis Intern Med J 2012 42 3 341 342 22432990

- Pitsis AA Visouli AN Update on ventricular assist device management in the ICU Curr Opin Crit Care 2008 14 5 569 578 18787451

- Arlt M Philipp A Voelkel S Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in severe trauma patients with bleeding shock Resuscitation 2010 81 7 804 809 20378236

- Muellenbach RM Kredel M Kunze E Prolonged heparin-free extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in multiple injured acute respiratory distress syndrome patients with traumatic brain injury J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012 72 5 1444 1447 22673280

- Siden HB Sanders GM Moler FW A report of four cases of acute, severe pulmonary hemorrhage in infancy and support with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation Pediatr Pulmonol 1994 18 5 337 341 7898974

- Sun LC Tseng YR Huang SC Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to rescue profound pulmonary hemorrhage due to idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis in a child Pediatr Pulmonol 2006 41 9 900 903 16850442

- Son SK Oh SH Kim KM Successful liver transplantation following veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a child with fulminant Wilson disease and severe pulmonary hemorrhage: a case report Pediatr Transplant 2012 16 7 E281 E285 22093921

- Keller R Torres S Iölster T Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and plasmapheresis in the treatment of severe pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to nodose polyarteritis Arch Argent Pediatr 2012 110 4 e80 e85 Spanish 22859338

- Lee JH Kim SW Successful management of warfarin-exacerbated diffuse alveolar hemorrhage using an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation Multidiscip Respir Med 2013 8 1 16 23442499

- Kotani K Ichiba S Andou M Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with nafamostat mesilate as an anticoagulant for massive pulmonary hemorrhage after living-donor lobar lung transplantation J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002 124 3 626 627 12202881

- Kolníková I Kunstýrˇ J Lindner J Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation used in a massive lung bleeding following pulmonary endarterectomy Prague Med Rep 2012 113 4 299 302

- Yıldızeli B Arslan O Taş S Management of massive pulmonary hemorrhage following pulmonary endarterectomy Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012

- Grimme I Winter R Kluge S Petzoldt M Hypoxic cardiac arrest in pregnancy due to pulmonary hemorrhage BMJ Case Rep 2012 2012

- Mongero LB Brodie D Cunningham J Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and severe hypoxemic respiratory failure from silicone embolism Perfusion 2010 25 4 249 252 discussion 253–254 20566586

- Daimon S Umeda T Michishita I Wakasugi H Genda A Koni I Goodpasture’s-like syndrome and effect of extracorporeal membrane oxygenator support Intern Med 1994 33 9 569 573 8000112

- Loscar M Hummel T Haller M ARDS and Wegener granulomatosis Anaesthesist 1997 46 11 969 973 German 9490585

- Kirby RR Lobato EB Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and pulmonary disease Chest 2005 127 1 413 15654013

- Weber TR Extending the uses of ECMO Chest 2004 126 1 9 10 15249434

- Bermudez CA Rocha RV Zaldonis D Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplant: midterm outcomes Ann Thorac Surg 2011 92 4 1226 1231 discussion 1231–1232 21872213

- Toyoda Y Bhama JK Shigemura N Efficacy of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to lung transplantation J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013 145 4 1065 1070 discussion 1070–1071 23332185