Abstract

Background and objective

Early readmissions of frail elderly patients after an episode of hospital care are common and constitute a crucial patient safety outcome. Our purpose was to study the impact of medications on such early rehospitalizations.

Patients and methods

This is a clinical, prospective, observational study on rehospitalizations within 30 days after an acute hospital episode for frail patients over the age of 75 years. To identify adverse drug reactions (ADRs), underuse of evidence-based treatment and avoidability of rehospitalizations, the Naranjo score, the Hallas criteria and clinical judgment were used.

Results

Of 390 evaluable patients, 96 (24.6%) were rehospitalized. The most frequent symptoms and conditions were dyspnea (n = 25) and worsened general condition (n = 18). The most frequent diagnoses were heart failure (n = 17) and pneumonia/acute bronchitis (n = 13). By logistic regression analysis, independent risk predictors for rehospitalization were heart failure (odds ratio [OR] = 1.8; 95% CI = 1.1–3.1) and anemia (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.3–4.0). The number of rehospitalizations due to probable ADRs was 13, of which two were assessed as avoidable. The number of rehospitalizations probably due to underuse of evidence-based drug treatment was 19, all of which were assessed as avoidable. The number of rehospitalizations not due to ADRs or underuse of evidence-based drug treatment was 64, of which none was assessed as avoidable.

Conclusion

One out of four frail elderly patients discharged from hospital was rehospitalized within 1 month. Although ADRs constituted an important cause of rehospitalization, underuse of evidence-based drug treatment might be an even more frequent cause. Potentially avoidable rehospitalizations were more frequently associated with underuse of evidence-based drug treatment than with ADRs. Efforts to avoid ADRs in frail elderly patients must be balanced and combined with evidence-based drug therapy, which can benefit these patients.

Introduction

Background

Frailty is a biological syndrome, implying reduced physiological reserves and vulnerability to stressors.Citation1,Citation2 Frailty is highly associated with functional decline, activity limitations and prolonged recovery for the individual. It also predicts a high risk of being institutionalized and dying within a short time.Citation3–Citation5 Frail elderly patients constitute a high percentage of individuals treated in specialized acute care units, and they are characterized by high use of health care resources.Citation6,Citation7

Early readmissions of frail elderly patients after an episode of hospital care are commonCitation8,Citation9 and constitute a crucial patient safety outcome and risk predictor. Early rehospitalization rates have been reported to be associated with age, comorbidity, length of hospital stay, polypharmacy, worsening of functional status,Citation10 severe morbidities at discharge, preadmis-sion activities of daily living (ADL), malignant disease, dementia, high educational level,Citation11 frailtyCitation12 and discharge from hospital based on patient’s own request.Citation13 The most frequent diagnosis-related causes are cardiovascular disease and pulmonary disease.Citation14 Several risk prediction models for hospital readmission have been described,Citation15,Citation16 and strategies to reduce readmissions have been outlined.Citation17 In a systematic review, however, most such interventions were reported to have limited, if any, effect.Citation18

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are defined as “any noxious, unintended, and undesired effect of a drug, excluding therapeutic failures, intentional and accidental poisoning, and drug abuse.”Citation19 Causality assessment scales have been widely used to determine the likelihood that an individual patient’s condition indeed is an ADR, i.e., that a drug caused the undesirable condition.Citation20,Citation21 There are also sets of criteria to assess the avoidability of an identified ADR.Citation22 Despite the presence of these scales, it can be very difficult to decide whether an adverse clinical event is really an ADR or due to worsening of the patient’s disease.Citation23,Citation24

Of all hospital admissions in older patients, several studies have reported 6–12% to be due to ADRs.Citation23,Citation25–Citation27 However, in a recent large study, 3.3% of admissions of patients aged 65 years or older were reported to be ADR related,Citation28 while in another study it was 18%.Citation29 Some ADR-related hospitalizations are unavoidable, but a substantial proportion of hospital admissions for ADRs has been judged to be avoidable,Citation29–Citation31 including ADRs due to missed contraindications, improper dosage, foreseeable drug interactions or reexposure of patients who have known drug allergies or other medication errors.Citation32 The main risk factors for ADR-related hospitalizations in older patients have been identified as advanced age, many drugs, multimorbidity and potentially inappropriate medications.Citation23,Citation33

ADRs are more frequently identified in frail elderly patients than in younger patients,Citation34,Citation35 and they are more likely to cause hospitalizations.Citation36 This is attributed to somatic age-related changes in the metabolism, i.e., the capacity of elimination of drugs, polypharmacy and morbidity implying an increased vulnerability in various organs. ADR risk also increases with a larger comorbidity burden, inappropriate prescribing and suboptimal monitoring of drugs.Citation37 The drugs that most frequently are reported to have caused an ADR are cardiovascular drugs, drugs with central nervous effects, anticoagulants and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The most common clinical manifestations are falls, orthostatic hypotension, bleeding, delirium and renal failure.Citation37

It has been pointed out that polypharmacy might be appropriate in some clinical contexts.Citation28,Citation38 Most studies have focused on overuse, or inappropriate use of drug treatments. However, the opposite can also be of significant importance. In one study, 13% of hospital admissions were assessed to be medication related, and including also underuse of evidence-based regimens.Citation39 Of these admissions, 20% were classified as preventable. Underuse of drugs in an elderly care context has been reported, even when there is reasonable evidence for beneficial effects also for elders, e.g., regarding anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation,Citation40,Citation41 Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and beta-blockers in heart failureCitation42,Citation43 and anti-dementia drugs.Citation44 Focusing on avoiding ADRs might lead to reductions in the potential benefits of drug therapy.Citation45

Importance

Early rehospitalizations of frail elderly patients are common and constitute a problem for the individual patient as well as for the health care system from a socioeconomic perspective. Polypharmacy is common for these patients, and ADRs have been pointed out as an important cause of admissions. However, there are also data indicating that underuse of evidence-based drug treatments in the elderly might be common even when clearly indicated. From a patient safety perspective, it is important to give a balanced description of the causes of early readmissions of frail elderly patients, including the role of medications.

Goals of the investigation

Our aim was to study the causes of early rehospitalizations of frail elderly patients, particularly in the context of medications, including both over- and underuse of evidence-based treatments.

Patients and methods

Study design and setting

This is a clinical, prospective, observational study. It was carried out at the NU County Hospital Group in the Västra Götaland region in Sweden between March 2013 and July 2015 within the study entitled “Is the treatment of frail elderly patients effective in an elderly care unit (TREEE).” The TREEE study was approved by the independent ethics committee at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden (8883-12, 20121212) and registered at the Swedish National Database of Research and Development; identifier 113021 (http://www.researchweb.org/is/vgr/project/113021; November 4, 2012).

Selection of participants

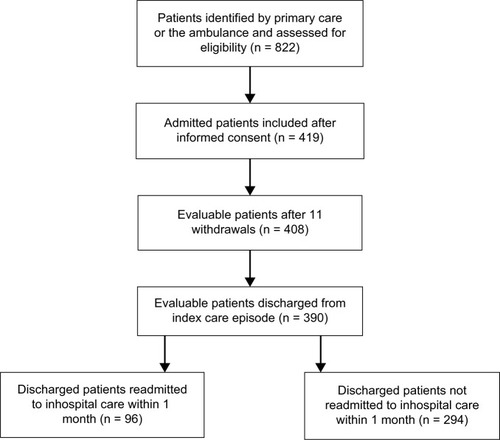

The selection of participants and primary data collection has been previously described.Citation46 In summary, a total of 419 patients were included, 408 of whom could be evaluated. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥75 years, screened as frail according to the validated FRail Elderly Support ResearcH (FRESH) group screening instrumentCitation47 and assessed as being in need of inpatient care. Two or more of the following criteria in the FRESH screening instrument implied frailty: tiredness from a short walk, general fatigue, frequent falls/anticipation of falls, dependence in shopping and three or more visits to the emergency ward during the past 12 months. Exclusion criteria included patients in acute need of care at an organ-specific medical unit, e.g., patients with an acute myocardial infarction or a strong suspicion of stroke. During the index care episode, 18 out of the 408 patients died before discharge. Thus, 390 patients who were discharged alive could be studied regarding early rehospitalizations and their causes (). All patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Methods and measurements

Clinical characteristics, hospital care consumption, rehospitalizations and mortality

The following data were collected from patients, medical records and registers during the index care episode and at the 3-month follow-up visit: age, gender, housing, diabetes mellitus, renal function, heart failure, other comorbidities, number of inhospital care days, rehospitalizations and mortality. ADL independence/dependence was assessed by using the ADL staircase before discharge.Citation48 The patient’s total burden of morbidity was measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index.Citation49 The degree of frailty was determined using the FRESH screening instrument.Citation47 The risk of malnutrition was assessed by the Mini Nutritional Assessment – short form (MNA-SF).Citation50 Polypharmacy was defined as 10 or more drugs in one patient.

Classification and characteristics of early rehospitalizations

Early rehospitalization was defined as occurring within 30 days from index hospitalization discharge. Classification of cause and characteristics of early rehospitalizations were made retrospectively from medical records by clinical judgment and through scoring scales. Two senior clinicians independently classified the early rehospitalization cases into one of three categories based on the most probable main cause: 1) probably due to ADR according to clinical judgment and/or Naranjo scoring; 2) probably due to underuse of evidence-based drug treatment according to clinical judgment; and 3) probably not due to ADRs or underuse of evidence-based drug treatment. When the clinical judgment was discordant, a third clinician performed a final judgment.

The classification included the Naranjo score to identify an ADR as the cause of the condition.Citation20,Citation21 A condition was classified as ADR if deemed probable or definite, i.e., if the Naranjo score was >4. Similarly probable avoidability of the rehospitalization was assessed by clinical judgment and, when an ADR was identified, the Hallas criteria.Citation22 If the Hallas criteria pointed out the ADR to be definitely avoidable, it was deemed to be avoidable in our study.

Early rehospitalization was classified as due to underuse of drug treatment when the absence of evidence-based treatment constituted the probable cause of the rehospitalization, and the indication was known at discharge and there was no absolute or relative contraindication.

Statistical analysis

The data were computerized and analyzed using the SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data are presented as mean, one SD and median (range). The Student’s t-test was used to calculate the 95% CI of the mean. Categorical data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test, and the continuous data were compared using Student’s t-test. When there was a significant difference, the Bonferroni post hoc test was used. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Regarding adjusted analysis of factors predicting early rehospitalizations, a logistic regression model was used.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

Of 390 evaluable patients discharged from the index care episode, 96 patients (24.6%) were rehospitalized within 30 days, while 294 patients were not (75.4%). Baseline characteristics of both groups are presented in . In unadjusted analysis, the groups did not differ significantly in terms of age, gender, total morbidity burden, living in residential care, own living with home help services, marital status, ADL, MNA, frailty score, duration of index hospital stay and most of the studied diagnoses (all p > 0.05). These data also indicate that disabilities, i.e., dependence or difficulty carrying out personal or instrumental ADL, were common among the participants in both groups. Both groups were heavily affected by diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease. The exceptions were that the early rehospitalized participants had a significantly higher baseline prevalence of chronic heart failure (p = 0.017), ane-mia (p = 0.001) and a higher prevalence of polypharmacy (p < 0.001). By logistic regression analysis, independent predictors for early rehospitalization were anemia (p = 0.0031) and chronic heart failure (p = 0.024), and none of the other baseline variables (p > 0.05).

Table 1 Baseline (index care episode) clinical and demographic characteristics of early readmitted patients (n=96) and patients not readmitted early (n=294), unadjusted analysis

Main results

Admission characteristics of early rehospitalized patients are presented in . The symptoms and conditions which most frequently caused readmissions were dyspnea (n = 25), worsened general condition/tiredness (n = 18), pain (n = 15), suspected infection (n = 14) and vertigo/falling (n = 10). The admission route was the ambulance for all these patients (n = 96). The four most frequent primary diagnoses at the index care episode for these patients in need of rehospitalization were pneumonia/exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/acute bronchitis (n = 21), heart failure (n = 19), urinary tract infection (n = 11) and other infectious disease (n = 9). The four most frequent primary diagnoses at the early rehospitalization episode were heart failure (n = 17), pneumonia/exacerbation of COPD/acute bronchitis (n = 13), other infectious disease (n = 10) and urinary tract infection (n = 8).

Table 2 Admission characteristics of early readmissions (n = 96)

Early rehospitalizations probably due to ADRs according to clinical judgment and/or Naranjo scoring (n = 13) are presented in . The number of ADRs according to clinical judgment was 13, and according to the Naranjo score was 9. The nine patients with ADRs according to the Naranjo score were included in the 13 clinical judgment patients. Of these early rehospitalizations probably due to an ADR, two were classified as probably avoidable by clinical assessment. The same two patients were classified as probably avoidable by the Hallas score. None of these 13 patients died.

Table 3 Early rehospitalizations probably due to ADRs according to clinical judgment and/or Naranjo scoringTable Footnote§

Early rehospitalizations identified through clinical judgment as probably due to underuse of evidence-based drug treatment, i.e., despite known indication at the index care episode and without known contraindication (n = 19), are presented in . The most frequently identified indications, not treated with evidence-based drug treatment, were heart failure (n = 11) and atrial fibrillation (n = 3). Of these 19 early rehospitalizations probably due to underuse of evidence-based drug treatment, all were classified as probably avoidable by clinical assessment. None of these 19 patients died.

Table 4 Early rehospitalization probably due to drug underuse, according to clinical judgmentTable Footnote§

Early rehospitalizations identified through clinical judgment as probably not due to ADRs or underuse of evidence-based drug treatment (n = 64) are presented in Table S1. None of these rehospitalizations were assessed as probably avoidable. Of these patients, eight died during the rehospitalization.

Regarding the comparison of the proportions of patients rehospitalized due to underuse of evidence-based drug treatment (19/96) and patients rehospitalized due to ADRs (13/96), there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.333). Regarding the comparison of the proportions of patients rehospitalized due to underuse of evidence-based drug treatment, assessed to be avoidable (19/96), and patients rehospitalized due to ADRs, assessed to be avoidable (2/96), there was a statistically significant difference (p < 0.0001).

Discussion

In this study, one out of four frail elderly patients was rehospitalized within 1 month after discharge from a hospitalization episode. The most frequently reported symptoms causing rehospitalization were dyspnea and tiredness, and the most frequently reported diagnoses were heart failure and infectious disease. Independent risk predictors for rehospitalization were heart failure and anemia at index hospitalization discharge.

ADRs were reported to be the main cause in 13 of the 96 (13.5%) rehospitalizations when assessment was performed through clinical judgment, and in nine of the 96 (9.4%) rehospitalizations when the Naranjo scale was used. In two of the 96 (2.1%) rehospitalizations, avoidable ADRs were assessed to be the main cause, according to clinical judgment as well as according to the Hallas avoidability criteria. The drugs most frequently reported to have caused an ADR were warfarin, digoxin and antidepressants. The most common clinical manifestations were bleeding, gastrointestinal symptoms and falls.

Underuse of evidence-based drug treatment, i.e., no treatment at discharge despite the known presence of an indication and the absence of contraindication, was assessed through clinical retrospective judgment to be the main probable cause of rehospitalization in 19 of the 96 (19.8%) patients. All of these undertreatment cases were assessed as potentially avoidable. The diagnoses most frequently associated with underuse of evidence-based drug treatment were heart failure and atrial fibrillation. The drugs that consequently most frequently were reported to be underused were ACE inhibitors/ARBs, beta-blockers and anticoagulants.

The rate of early rehospitalizations in this study is higher compared to most previous reports.Citation8,Citation9 This is most probably due to the characteristics of our study population including high age, multimorbidity and frailty, which are all considered to predict rehospitalizations.

ADRs constituted the probable main cause of readmission for 9.4–13.5% of the patients, which resembles the percentages reported in previous studies.Citation23 Only two avoidable ADRs as main cause of readmission were identified, i.e., 15.4% (2/13) up to 22.2% (2/9) of all ADRs causing rehospitalizations. This proportion is lower than reported in some previous studies,Citation30,Citation31 although similar to the percentage avoidable ADRs reported in a recent study.Citation29 Furthermore, extrapolating this proportion of rehospitalizations due to avoidable ADRs to a clinical population of frail elderly would imply that many patients are affected.

Underuse of evidence-based drug treatment was assessed to be the main probable cause in as much as 19.8% of rehospitalizations in our study, and all of these were assessed to be potentially avoidable. This was based on the presumption that the symptoms causing rehospitalizations, e.g., dyspnea from heart failure, might have been prevented or delayed by evidence-based drug therapy. This estimate might even be conservative, since in cases of a relative, rather than an absolute, contraindication we did not classify the rehospitalization as due to underuse of drug treatment. To our knowledge, very few trials have studied early rehospitalizations from this viewpoint. However, in one study, 13% of hospital admissions were assessed to be medication related including underuse of evidence-based regimens. Of these admissions, 20% were classified as preventable.Citation39

Evidence-based use of drugs has a definite potential to benefit also elderly patients, in some cases even more than in younger patients, since the disease-related risk usually is higher. Despite that the majority of publications focus on drug overuse in the elderly, there are also indications of underuse of drugs, even when there is reasonable evidence for beneficial effects also for elders, e.g., regarding atrial fibrillation (anticoagulants) and heart failure (ACE inhibitors/ARBs and beta-blockers). Powerful efforts to avoid all possible ADRs might switch the benefit–risk balance and lead to suboptimal use of evidence-based drug therapy.Citation45

It is a strength that our study included very frail elderly patients with a heavy comorbidity burden, while these patients would be excluded in most clinical trials. Further, most previous trials studying rehospitalizations of elderly have focused on ADRs, while our aim to describe both ADRs and underuse of drugs, i.e., a balanced perspective, comes closer to the considerations and trade-offs which have to be made in the daily clinical work. Moreover, it is a strength that we combined clinical assessment of ADRs and underuse of drugs with the use of two of the most common assessment scales, including judgment of the avoidability.

One limitation of the study is that it is based on secondary analyses, although in fact outlined in the original study protocol. Further, although the clinical assessments were made in an assessor-blinded fashion, the filling up of the assessment scales was not blinded. On the other hand, the latter assessments did not differ markedly from the former ones, which points to a limited risk of bias. The study sample was mid-sized, and a larger number of patients would have strengthened the results. Further, an even broader approach regarding drug therapy could be valuable in future research.Citation51–Citation53 We were not able to specifically investigate the effects of possible drug interactions in this study population. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that such interactions could have been involved in a few of the reported rehospitalizations.

Powerful patient safety efforts to avoid ADRs might lead to underestimation of the potential benefits of evidence-based drug therapy. This might have negative consequences for the elderly patients, and for the health care system as well. There is a need for larger studies of frail elderly patients, including evaluating rehospitalizations, which take both the perspective of underuse of drugs and ADRs into account.

Conclusion

In this study, one out of four frail elderly patients discharged from hospital were rehospitalized within 1 month. Independent risk predictors for rehospitalization were heart failure and anemia. Although ADRs constituted an important cause of rehospitalizations, assessed underuse of evidence-based drug treatment might be an even more frequent cause. Moreover, potentially avoidable rehospitalizations were more frequently associated with underuse of evidence-based drug treatment than with ADRs, although this finding should be interpreted with caution, since the number of avoidable ADR readmissions was small in this study. Reasonable patient safety efforts made to avoid ADRs in frail elderly patients must be balanced and combined with evidence-based drug therapy which can benefit these patients. This implies a need for intensified educational efforts regarding drug therapy for frail elderly patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the Healthcare Subcommittee, Region Västra Götaland; Department of Research and Development, NU Hospital Group and the Fyrbodal Research and Development Council, Region Västra Götaland, Sweden. We acknowledge Göran Östberg and Maria Johansson for valuable discussions regarding clinical judgments in the study.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Early rehospitalizations probably not due to ADRs or underuse of evidence-based drug treatment

Disclosure

Björn W Karlson is an employee of AstraZeneca. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BergmanHFerrucciLGuralnikJFrailty: an emerging research and clinical paradigm. Issues and controversiesJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200762773173717634320

- ChenXMaoGLengSXFrailty syndrome: an overviewClin Interv Aging2014943344124672230

- FriedLPTangenCMWalstonJCardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research GroupFrailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotypeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2001563146156

- RockwoodKSongXMacKnightCA global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly peopleCMAJ2005173548949516129869

- ButaBJWalstonJDGodinoJGFrailty assessment instruments: systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instrumentsAgeing Res Rev201626536126674984

- WoodardJGladmanJConroySFrail older people at the interfaceAge Ageing201039S1i36

- EdmansJBradshawLFranklinMGladmanJConroySSpecialist geriatric medical assessment for patients discharged from hospital acute assessment units: randomised controlled trialBMJ2013347f587424103444

- DharmarajanKHsiehAFLinZDiagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumoniaJAMA2013309435536323340637

- BrennanJJChanTCKilleenJPCastilloEMInpatient readmissions and emergency department visits within 30 days of a hospital admissionWest J Emerg Med20151671025102926759647

- MorandiABellelliGVasilevskisEEPredictors of rehospitalization among elderly patients admitted to a rehabilitation hospital: the role of polypharmacy, functional status and length of stayJ Am Med Dir Assoc2013141076176723664484

- ZanocchiMMaeroBMartinelliEEarly re-hospitalization of elderly people discharged from a geriatric wardAging Clin Exp Res2006181636916608138

- HubbardREO’MahonyMSWoodhouseKWCharacterising frailty in the clinical setting: a comparison of different approachesAge Ageing200938111511919008304

- MahmoudiSTaghipourHRJavadzadehHRGhaneMRGoodarziHKalantar MotamediMHHospital readmission through the emergency departmentTrauma Mon2016212e3513927626018

- FabbianFBoccafogliADe GiorgiAThe crucial factor of hospital readmissions: a retrospective cohort study of patients evaluated in the emergency department and admitted to the department of medicine of a general hospital in ItalyEur J Med Res2015201625623952

- KansagaraDEnglanderHSalanitroARisk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic reviewJAMA2011306151688169822009101

- AlassaadAMelhusHHammarlund-UdenaesMBertilssonMGillespieUSundströmJA tool for prediction of risk of rehospitalisation and mortality in the hospitalised elderly: secondary analysis of clinical trial dataBMJ Open201552e007259

- KripalaniSTheobaldCNAnctilBVasilevskisEEReducing hospital readmission: current strategies and future directionsAnnu Rev Med20146547148524160939

- LinertováRGarcía-PérezLVázquez-DíazJRLorenzo-RieraASarría-SantameraAInterventions to reduce hospital readmissions in the elderly: in-hospital or home care. A systematic reviewJ Eval Clin Pract20111761167117520630005

- World Health OrganizationInternational Drug Monitoring: The Role of the HospitalGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health OrganizationWHO Tech Rep Ser No. 4251966

- NaranjoCABustoUSellersEMA method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactionsClin Pharmacol Ther19813022392457249508

- BelhekarMNTaurSRMunshiRPA study of agreement between the Naranjo algorithm and WHO-UMC criteria for causality assessment of adverse drug reactionsIndian J Pharmacol201446111712024550597

- HallasJHarvaldBGramLFDrug related hospital admissions: the role of definitions and intensity of data collection, and the possibility of preventionJ Intern Med1990228283902394974

- Parameswaran NairNChalmersLPetersonGMBereznickiBJCastelinoRLBereznickiLRHospitalization in older patients due to adverse drug reactions –the need for a prediction toolClin Interv Aging20161149750527194906

- HamiltonHJGallagherPFO’MahonyDInappropriate prescribing and adverse drug events in older peopleBMC Geriatr20099519175914

- MarcumZAAmuanMEHanlonJTPrevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veteransJ Am Geriatr Soc2012601344122150441

- ConfortiACostantiniDZanettiFMorettiUGrezzanaMLeoneRAdverse drug reactions in older patients: an Italian observational prospective hospital studyDrug Healthc Patient Saf20124758022888275

- ChanSLAngXSaniLLPrevalence and characteristics of adverse drug reactions at admission to hospital: a prospective observational studyBr J Clin Pharmacol20168261636164627640819

- PedrósCFormigaFCorbellaXArnauJMAdverse drug reactions leading to urgent hospital admission in an elderly population: prevalence and main featuresEur J Clin Pharmacol201672221922626546335

- RydbergDMHolmLEngqvistIAdverse drug reactions in a tertiary care emergency medicine ward – prevalence, preventability and reportingPLoS One2016119e016294827622270

- ChanMNicklasonFVialJHAdverse drug events as a cause of hospital admission in the elderlyIntern Med J200131419920511456032

- Bénard-LaribièreAMiremont-SalaméGPérault-PochatMCNoizePHaramburuFEMIR Study Group on Behalf of the French Network of Pharmacovigilance CentresIncidence of hospital admissions due to adverse drug reactions in France: the EMIR studyFundam Clin Pharmacol201529110611124990220

- VazinAZamaniZHatamNFrequency of medication errors in an emergency department of a large teaching hospital in southern IranDrug Healthc Patient Saf2014617918425525391

- PedrósCQuintanaBRebolledoMPortaNVallanoAArnauJMPrevalence, risk factors and main features of adverse drug reactions leading to hospital admissionEur J Clin Pharmacol201470336136724362489

- MangoniAAPredicting and detecting adverse drug reactions in old age: challenges and opportunitiesExpert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol20128552753022512705

- DaviesEAO’MahonyMSAdverse drug reactions in special populations – the elderlyBr J Clin Pharmacol201580479680725619317

- BudnitzDSPollockDAWeidenbachKNMendelsohnABSchroederTJAnnestJLNational surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug eventsJAMA2006296151858186617047216

- LavanAHGallagherPPredicting risk of adverse drug reactions in older adultsTher Adv Drug Saf201671112226834959

- PayneRAAbelGAAveryAJMercerSWRolandMOIs polypharmacy always hazardous? A retrospective cohort analysis using linked electronic health records from primary and secondary careBr J Clin Pharmacol20147761073108224428591

- KalischLMCaugheyGEBarrattJDPrevalence of preventable medication-related hospitalizations in Australia: an opportunity to reduce harmInt J Qual Health Care201224323924922495574

- PughDPughJMeadGEAttitudes of physicians regarding anti-coagulation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic reviewAge Ageing201140667568321821732

- FoodyJMReducing the risk of stroke in elderly patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a practical guide for cliniciansClin Interv Aging20171217518728182166

- KomajdaMHanonOHochadelMContemporary management of octogenarians hospitalized for heart failure in Europe: Euro Heart Failure Survey IIEur Heart J200930447848619106198

- Díez-VillanuevaPAlfonsoFHeart failure in the elderlyJ Geriatr Cardiol201613211511727168735

- AllegriNRossiFDel SignoreFDrug prescription appropriateness in the elderly: an Italian studyClin Interv Aging20171232533328228653

- BudnitzDSLovegroveMCShehabNRichardsCLEmergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older AmericansN Engl J Med2011365212002201222111719

- EkerstadNKarlsonBWDahlin-IvanoffSIs the acute care of frail elderly patients in a comprehensive geriatric assessment unit superior to conventional acute medical care?Clin Interv Aging2017121928031704

- EklundKWilhelmssonKLandahlSIvanoff-DahlinSScreening for frailty among older emergency department visitors: validation of the new FRESH-screening instrumentBMC Emerg Med20161612727449526

- SonnUHulter-ÅsbergKAssessment of activities of daily living in the elderlyScand J Rehabil Med19912341932021785028

- CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCRA new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validationJ Chronic Dis19874053733833558716

- RubensteinLZHarkerJOSalvàAGuigozYVellasBScreening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF)J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2001566M366M37211382797

- Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC)The Patient-Centered Medical Home: Integrating Comprehensive Medication Management to Optimize Patient Outcomes. Resource Guide2nd edWashington, DCPatient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative2012

- ForsterAJMurffHJPetersonJFGandhiTKBatesDWThe incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospitalAnn Intern Med2003138316116712558354

- ForsterAJMurffHJPetersonJFGandhiTKBatesDWAdverse drug events occurring following hospital dischargeJ Gen Intern Med200520431732315857487