Abstract

Background:

The US Food and Drug Administration has issued warnings about a potential link between leukotriene receptor-modifying agents (LTMA) and suicide. These warnings are based on case reports and there is controversy about the association. While spontaneous reporting of suicide-related events attributed to LTMA has risen dramatically, these data may be biased by the warnings. The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between LTMA and suicide deaths using event data preceding the Food and Drug Administration warnings.

Methods:

We conducted a mixed-effects Poisson regression analysis of the association between LTMA prescriptions dispensed and suicide deaths at the county level. Counts of suicide deaths in each US county, stratified by race, age group, gender, and year were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics for the period January 1, 1999 to December 31, 2006. Counts of LTMA prescriptions dispensed in each US county were obtained from IMS Health Incorporated. The model estimated the overall suicide rate conditional on LTMA use, adjusted for age, gender, race, year, and antidepressant utilization. We also assessed the intracounty and intercounty associations.

Results:

There were 249,872 suicides in the US between 1999 and 2006, and the annual suicide rate ranged from 11.17 to 11.92 per 100,000 population. There were 118.63, 11.68, and 0.12 million prescriptions dispensed for montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton, respectively, between 1999 and 2006. The mean rate of LTMA prescriptions dispensed by county was 42.91 (95% confidence interval [CI] 42.78–43.04), 4.82 (95% CI 4.81–4.84), and 0.05 (95% CI 0.05–0.05) per 1000 for montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton, respectively. We found a negative within-county association between the rate of total LTMA prescriptions dispensed and the suicide rate by county (P = 0.0296). This association was primarily driven by montelukast.

Conclusion:

Our results, while subject to certain limitations, provide preliminary evidence that the association between LTMA and suicide could be different (ie, reduced risk) than that which might be anticipated based on previous warnings. Patient-level research is needed to understand more clearly the association between LTMA and suicide.

Introduction

In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning about a potential link between montelukast (Singulair®, Merck & Co Inc, Whitehouse Station, NJ) and suicide.Citation1 Later, the warning was expanded to all leukotriene receptor-modifying agents (LTMA).Citation2,Citation3 These warnings were based primarily on information from case reports. Subsequently, several retrospective evaluations of clinical trial data were conducted, but these found no elevated risk of suicide or other behavior-related adverse events in those treated with LTMA compared with placebo.Citation3–Citation6 As a result there was, and remains, controversy about the proposed association.Citation7

Following the initial FDA warning, there was a sharp increase in the number of suicide-related events reported to the FDA’s Adverse Events Reporting System where LTMA were considered the suspect drug.Citation8 Over 800 such events were reported in 2008 and 2009, while only 33 were reported during the 10 years prior to the FDA warnings. The timing of these “spontaneous reports” in relation to FDA warnings makes it difficult to make conclusions about the association using these data.

In the case of suicides, other sources of data are available that may be used to investigate drug-event associations, while avoiding the limitations associated with spontaneously reported adverse events data. Gibbons et al used data from the National Center for Health Statistics, a division of the Centers for Disease Control of the US Department of Health and Human Services, to obtain the number of suicides by county in the US. These data were combined with prescription rates for antidepressants to examine the association between antidepressants and suicides.Citation9,Citation10 Here we apply the same methodology to explore further the potential association between LTMA and suicide.

Methods

We conducted a mixed-effects Poisson regression analysis of the association between LTMA prescriptions dispensed and suicides at the county level (ie, county was the clustering variable). Annual counts of suicide deaths occurring in each county of the US were obtained from the Compressed Mortality File available from the National Center for Health Statistics for the period January 1, 1999 to December 31, 2006 (most recent available).Citation11 Mortality data in the Compressed Mortality File are based on information from all death certificates filed in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, excluding deaths of nonresidents (eg, deaths of nonresident aliens, nationals residing abroad, and residents of Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, and other territories of the US) and fetal deaths. The suicide counts we obtained for each county were stratified by race (black or nonblack), age group (5–14, 15–24, 25–44, 45–64, and 65 years and older), gender, and year. The population of each county for these same subgroups was also obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics.

We obtained counts of the number of LTMA prescriptions dispensed in each county of the US from the Xponent™ database, IMS Health Incorporated, for the same time period. These data were based on total dispensed prescriptions from retail (chain, independent, food stores, and mass merchandisers) pharmacies in the US. These data were not available for the demographic subgroups as were the Centers for Disease Control data. Further, these data do not provide information on whether the prescriptions were taken by patients, nor do they provide information on the number of patients taking the medications. Nevertheless, these data are commonly used for measuring prescription dispensations and are a reliable representation of total prescriptions dispensed in the US. Because antidepressant use has been associated with suicide, we also obtained counts of antidepressant prescriptions dispensed by county from the IMS database to use as a covariate in our analysis.

To relate LTMA prescription use to suicide rate, adjusting for county-specific sociodemographic characteristics, we used a mixed-effects Poisson regression model in a manner similar to that of Gibbons et al.Citation9,Citation10 The model estimated the overall suicide rate conditional on age, gender, race, year, and LTMA use. We also included antidepressant drug prescriptions dispensed as a covariate. In one model, LTMA were combined into a single variable, and in another each LTMA (montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton) was included separately to examine individual drug effects. To account for differential population sizes across counties, counts of LTMA and antidepressant prescriptions dispensed were divided by the population of each county in each year. To decompose the overall relationship between suicides and LTMA prescriptions dispensed into intracounty and intercounty components, we included in the models, variables representing the county mean drug prescriptions and a yearly deviation from the mean for each LTMA. In the models, age, gender, race, year, anti-depressant prescriptions dispensed, and LTMA prescriptions dispensed were considered fixed effects, while the intercept (ie, county) was treated as a random effect.

Results

There were 249,872 suicides in the US between 1999 and 2006 (inclusive). As shown in , the annual suicide rate for the entire population ranged from 11.17 per 100,000 (in 2000) to 11.92 per 100,000 (in 2006), with an average of 11.61 per 100,000 for the entire time period. The rate varied widely by age group, race, and gender, with nonblack males having the highest rates (20.18 per 1000) and black females the lowest (1.80 per 1000). We also calculated suicide rates at the county level. These varied widely with an average county-level suicide rate over the entire time period of 11.42 per 100,000 (95% confidence interval [CI] 11.40–11.45).

Table 1 Observed suicide rates by age, race, and gender for each year (1999–2006). The rates shown in this table were calculated using the number of suicide deaths and the population by group, both of which were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics, for the period January 1, 1999 to December 31, 2006

There were 118.63, 11.68, and 0.12 million prescriptions dispensed for montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton, respectively, between 1999 and 2006. Adjusted for the population, the rate of prescriptions was 55.10, 5.19, and 0.05 per 1000, as shown in . These rates varied by year. The mean LTMA prescription dispensing rate by county was 42.91 per 1000 (95% CI 42.78–43.04) for montelukast, 4.82 per 1000 (95% CI 4.81–4.84) for zafirlukast, and 0.05 (95% CI 0.053–0.054) per 1000 population for zileuton.

Table 2 Observed rate of prescriptions dispensed for leukotriene-modifying agents by year. The rates shown were calculated using the number of prescriptions dispensed for each leukotriene-modifying agent, which was obtained from the Xponent™ database, IMS Health Incorporated (all rights reserved), January 1, 1999 to December 31, 2006; and along with the population data which were obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics, for the same period

Adjusting for county-specific sociodemographic characteristics and antidepressant use, we found a negative within-county association between the rate of total LTMA prescriptions dispensed and the suicide rate. Specifically, we observed that within a given county a one unit increase in prescriptions dispensed for LTMA (ie, one prescription per 1000 population) was associated with a 0.03% decrease in the suicide rate (maximum marginal likelihood estimate = −0.0003, P = 0.0296). The between-county effect was not significant. To determine whether the observed association was specific to only certain drugs in the LTMA class, we fit a model containing each of the individual drugs. Here we found a statistically significant negative (within-county but not between-county) association for montelukast (maximum marginal likelihood estimate = −0.0003, P = 0.0217), but not zafirlukast (maximum marginal likelihood estimate = −0.0016, P = 0.1687) or zileuton (maximum marginal likelihood estimate = −0.0022, P = 0.8890), although the direction of the effect was consistent across all three drugs. The estimated rate multiplier for the montelukast within-county effect was 0.9997 (95% CI 0.9994–0.9999), which means that for every unit increase in montelukast prescriptions (ie, one prescription per 1000 population) there is a corresponding decrease in the rate of suicides by 0.03%.

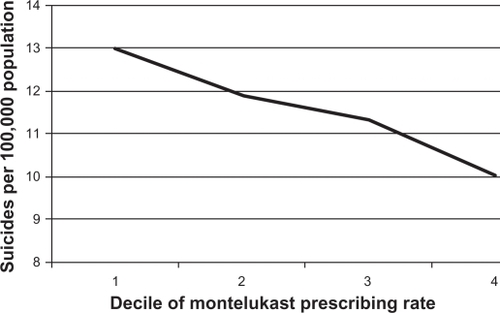

shows graphically the relationship between county-level rate of montelukast prescriptions dispensed and the county-level suicide rate. The horizontal axis is montelukast prescriptions dispensed per 1000 population in quartiles, while the corresponding mean suicide rate per 100,000 is shown on the vertical axis. For example, the mean suicide rate for counties in the lowest quartile of montelukast prescriptions dispensed per 1000 population was 12.97, while the rate was 10.02 in the highest quartile. shows visually the negative association described above.

Figure 1 Relationship between county-level montelukast prescribing rate per 1000 population and county-level suicide rate per 100,000 population, 1999–2006. The horizontal axis is montelukast prescriptions dispensed per 1000 population in quartiles, while the corresponding mean suicide rate per 100,000 is shown on the vertical axis. For example, the mean suicide rate for counties in the lowest quartile of montelukast prescriptions dispensed per 1000 population was 12.97, while the mean rate was 10.02 for counties in the highest quartile. The number of suicide deaths by county and the population by county were obtained from the National Center For Health Statistics, for the period January 1, 1999 to December 31, 2006, and was used to calculate the suicide rate. The number of prescriptions for montelukast by county was obtained from the Xponent™ database, IMS Health Incorporated (all rights reserved), for the same time period, and along with the population data was used to calculate the rate of montelukast prescriptions dispensed per 1000 population.

Discussion

Our analysis was performed by combining county-level data on suicide deaths with data on prescriptions dispensed for LTMA, and as such was intended to be exploratory. Our main observation, ie, that as the number of prescriptions dispensed for montelukast increases within a given county the rate of suicides decreases, is contrary to that which one might anticipate, given the FDA warnings about LTMA and the subsequent increase in spontaneous reports of suicides linked to montelukast. Such a finding does not necessarily negate the importance of the FDA warning, which is intended to alert prescribers and the public about the possibility that the development of suicidal thoughts or actions may occur in some patients. After all, it is possible that in some patients the drug(s) increase risk while in others risk is mitigated. Nevertheless, because such warnings can result in important drugs being withheld from patients who might otherwise benefit from them, it is important to conduct research that might better inform clinical decision-making.

It is not clear how montelukast may reduce suicides, if indeed that is the case. However, both asthma and allergic rhinitis, ie, the two FDA-approved indications for montelukast, are associated with increased risk for suicide and related behavior. Asthma has also been associated with a 2–3 times higher risk for suicidal ideation,Citation12–Citation14 and more than four times higher likelihood of suicide attempts.Citation14,Citation15 Some data suggest that asthma symptoms, including “breathlessness”, pain, and functional limitations, may contribute to suicide, possibly via depression.Citation16 Similarly, higher rates of suicide have been observed in those with allergic rhinitis and other allergic disorders, and seasonal variation in suicide rates has been linked to corresponding peaks in disease.Citation17–Citation19 It is proposed that seasonal increases in pollen may result in onset of symptoms of the disease which then lead to worsening mood or depression, ie, the most common risk factor for suicide.Citation20 Allergic conditions have also been associated with anxiety, depression, hostility/aggression, and sleep disturbance, all of which in turn may be associated with suicide.Citation21–Citation25

Better control of asthma or allergic rhinitis results in reduced symptoms of disease. Therefore, a reasonable explanation of our finding could be that LTMA, because they are effective in reducing symptoms, reduce the risk of suicide. Still, our results should be considered in the context of the limitations present in our data and in our study design. This was an ecologic study that, like all such studies, had certain limitations that could have confounded our results. These are described in the following paragraphs.

We obtained data on suicides from the National Center for Health Statistics. These data are derived from death certificates. Biases associated with miscoding on death certificates have been previously discussed.Citation26 However, the sensitivity and specificity of coding of deaths due to suicide has been shown to be very high (>90%).Citation27 Nevertheless, some uncontrolled variability may exist due to differences at the county level in qualifications of coroners or medical examiners, frequency and extent of case investigations, and definitions of suicide, which may lead to differential suicide rates. The population estimates for subgroups (by age, gender, race) within counties were also obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics Compressed Mortality File. These estimates are projected based on previous census figures and may not be accurate in counties where demographics are changing rapidly.

In our analysis we also used data on retail prescriptions for LTMA dispensed in the US. While the retail distribution channel from which these data come likely captured a majority of the use of these drugs, some utilization may occur in hospitals, mail order pharmacies, or other settings not included in these data. Further, while the data we used are projected to account for 100% of the market, the accuracy of such projections at the county level is unknown. It is also true that prescriptions dispensed are not necessarily the same as exposure because of the inability to measure patient adherence. However, there is substantial literature validating the use of prescription claims as a measure of drug exposure.Citation28,Citation29 Last, while there was substantial use of montelukast across the US in our data, the lower overall rate of prescriptions for zafirlukast and zileuton may have limited our power to detect an association with these drugs if one had existed.

Finally, while we controlled for a number of factors that could confound our results, the data sources we used did not contain many variables that could help us to adjust for confounding in the relationship between LTMA use and suicide. For example, we did not control for county-level prevalence of asthma or allergic rhinitis, or for other diseases (ie, mental disorders), behaviors (ie, drug abuse or alcoholism), or socioeconomic factors that have been shown to increase the risk of suicide. Nor did we control for homicide or fatal accident rates, availability of mental health services, or use of prescription drugs other than antidepressants that may be associated with suicide.

Because our study was ecologic in nature, we are not able to draw any causal inferences from these data. Nevertheless, these results raise questions about the potential LTMA-suicide relationship and provide preliminary evidence, at least for montelukast, that for some patients the association may actually be in the opposite direction (ie, reduced risk) of that anticipated from the warnings. Clearly, additional patient-level research is needed to establish the presence of an association between LTMA and suicide more definitively, and to understand better if there might be subgroups of patients that differ with respect to level of risk or even direction of effect.

Disclosure

No funding was received for the conduct of this study. Dr Lee has served as a consultant for Merck and has been an investigator on a grant funded in part by Astra Zeneca – both of which are manufacturers of drugs included in this study. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. All persons who made substantial contributions to the work are included as authors. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from the following IMS Health Incorporated information service(s): Xponent™, January 1999 – December 2009, IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. Such statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions are not necessarily those of IMS Health Incorporated or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities. Similarly, data from the National Center for Health Statistics as used in this analysis. All analysis, interpretations, and conclusions reached from these data are those of the authors and not the National Center for Health Statistics.

References

- US Food and Drug AdministrationEarly communication about an ongoing safety review of montelukast (Singulair), 2009 Postmarket drug safety information for patients and providers. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/drugsafetyinformationforhealthcareprofessionals/ucm070618.htm. Accessed June 24, 2011.

- US Food and Drug AdministrationUpdated information on leukotriene inhibitors: Montelukast (marketed as Singulair), zafirlukast (marketed as Accolate), and zileuton (marketed as Zyflo and Zyflo CR), 2009 Post-market drug safety information for patients and providers. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/drugsafetyinformationforhealthcareprofessionals/ucm165489.htm. Accessed June 24, 2011.

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFollow-up to the March 27, 2008 communication about the ongoing safety review of montelukast (Singulair), 2009 Postmarket drug safety information for patients and providers. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/drugsafetyinformationforhealthcareprofessionals/ucm079523.htm. Accessed June 24, 2011.

- BisgaardHSkonerDBozaMLSafety and tolerability of montelukast in placebo-controlled pediatric studies and their open-label extensionsPediatr Pulmonol200944656857919449366

- PhilipGHustadCNoonanGReports of suicidality in clinical trials of montelukastJ Allergy Clin Immunol2009124469169619815114

- PhilipGHustadCMMaliceMPAnalysis of behavior-related adverse experiences in clinical trials of montelukastJ Allergy Clin Immunol2009124469970619815116

- [No authors listed].Joint statement on FDA investigation of Singulair from the ACAAI and AAAAIEur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol200840264

- SchumockGTLeeTAJooMJValuckRJStaynerLTGibbonsRDAssociation between leukotriene-modifying agents and suicide: What is the evidence?Drug Saf201134753354421663330

- GibbonsRDHurKBhaumikDKMannJJThe relationship between antidepressant medication use and rate of suicideArch Gen Psychiatry200562216517215699293

- GibbonsRDHurKBhaumikDKMannJJThe relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicideAm J Psychiatry2006163111898190417074941

- National Center for Health StatisticsCompressed Mortality File, 1999–2006Hyattsville, MDNational Center for Health Statistics2009

- GoodwinRDOlfsonMSheaSAsthma and mental disorders in primary careGen Hosp Psychiatry200325647948314706414

- GoodwinRDMarusicAAsthma and suicidal ideation among youth in the communityCrisis20042539910215387235

- GoodwinRDEatonWWAsthma, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts: Findings from the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area follow-upAm J Public Health200595471772215798135

- DrussBPincusHSuicidal ideation and suicide attempts in general medical illnessesArch Intern Med2000160101522152610826468

- HarwoodDMHawtonKHopeTHarrissLJacobyRLife problems and physical illness as risk factors for suicide in older people: A descriptive and case-control studyPsychol Med20063691265127416734947

- TimonenMViiloKHakkoHIs seasonality of suicides stronger in victims with hospital-treated atopic disorders?Psychiatry Res2004126216717515123396

- MassingWAngermeyerMCThe monthly and weekly distribution of suicideSoc Sci Med19852144334414049013

- ChewKSMcClearyRThe spring peak in suicides: A cross-national analysisSoc Sci Med19954022232307899934

- PostolacheTTStillerJWHerrellRTree pollen peaks are associated with increased nonviolent suicide in womenMol Psychiatry200510323223515599378

- PostolacheTTKomarowHTonelliLHAllergy: A risk factor for suicide?Curr Treat Options Neurol200810536337618782509

- GoodwinRDCastroMKovacsMMajor depression and allergy: Does neuroticism explain the relationship?Psychosom Med2006681949816449417

- TimonenMJokelainenJHervaAZittingPMeyer-RochowVBRasanenPPresence of atopy in first-degree relatives as a predictor of a female proband’s depression: Results from the northern Finland 1966 birth cohortJ Allergy Clin Immunol200311161249125412789225

- TimonenMJokelainenJHakkoHAtopy and depression: Results from the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort studyMol Psychiatry20038873874412888802

- TimonenMJokelainenJSilvennoinen-KassinenSAssociation between skin test diagnosed atopy and professionally diagnosed depression: A Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort studyBiol Psychiatry200252434935512208642

- RosenbergHImproving cause-of-death statisticsAm J Public Health19897955635642705587

- MoyerLABoyleCAPollockDAValidity of death certificates for injury-related causes of deathAm J Epidemiol19891305102410322683747

- AndradeSEKahlerKHFrechFChanKAMethods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databasesPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200615856557416514590

- LauHSDe BoerABeuningKSPorsiusAValidation of pharmacy records in drug exposure assessmentJ Clin Epidemiol19975056196259180655