Abstract

Purpose

To assess the safety of duloxetine with regards to bleeding-related events in patients who concomitantly did, versus did not, use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin.

Methods

Safety data from all placebo-controlled trials of duloxetine conducted between December 1993 and December 2010, and post-marketing reports from duloxetine-treated patients in the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), were searched for bleeding-related treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs). The percentage of patients with bleeding-related TEAEs was summarized and compared between treatment groups in all the placebo-controlled studies. Differences between NSAID user and non-user subgroups from clinical trial data were analyzed by a logistic regression model that included therapy, NSAID use, and therapy-by-NSAID subgroup interaction. In addition, to determine if higher duloxetine doses are associated with an increased incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs, and whether the use of concomitant NSAIDs might influence the dose effect if one exists, placebo-controlled clinical trials with duloxetine fixed doses of 60 mg, 120 mg, and placebo were analyzed. Also, the incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs reported for duloxetine alone was compared with the incidence in patients treated with duloxetine and concomitant NSAIDs. Finally, the number of bleeding-related cases reported for duloxetine in the FAERS database was compared with the numbers reported for all other drugs.

Results

Across duloxetine clinical trials, there was a significantly greater incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs in duloxetine- versus placebo-treated patients overall and also in those patients who did not take concomitant NSAIDS, but no significant difference was seen among those patients who did take concomitant NSAIDS. There was no significant difference in the incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs in the subset of patients treated with duloxetine 120 mg once daily versus those treated with 60 mg once daily regardless of concomitant NSAID use. The combination of duloxetine and NSAIDs was associated with a statistically significantly higher incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs compared with duloxetine alone. A similarly higher incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs was seen in patients treated with placebo and concomitant NSAIDs compared with placebo alone. Bleeding-related TEAEs reported in the FAERS database were disproportionally more frequent for duloxetine taken with NSAIDs compared with the full FAERS background, but there was no difference in the reporting of bleeding-related TEAEs when the cases reported for duloxetine taken with NSAIDs were compared against the cases reported for NSAIDs alone.

Conclusion

Concomitant use of NSAIDs was associated with a higher incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs in clinical trials regardless of whether patients were taking duloxetine or placebo; bleeding-related TEAEs did not appear to increase along with duloxetine dose regardless of NSAID use. In spontaneously reported post-marketing data, the combination of duloxetine and NSAID use was not associated with an increased reporting of bleeding-related events when compared to NSAID use alone.

Introduction

Medications that modulate serotoninergic neurotransmission, like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), are commonly prescribed to treat depression, anxiety disorders, and premenstrual dysphoria,Citation1 as well as chronic pain conditions. During the past decade, numerous reports have been published on the risk of abnormal gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding as an infrequent adverse event (AE) associated with serotonin-modulating drugs.Citation2 Patients with musculoskeletal pain conditions, as well as patients with depression and anxiety who experience chronic pain, may also be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) including aspirin, which are also associated with GI bleeding.Citation3,Citation4 Concomitant use of NSAIDs with SSRIs or SNRIs may potentiate bleeding-related AEs.Citation5

The tendency for GI bleeding during treatment with serotonin-modulating drugs is linked to a decrease in blood platelet function that is dependent on serotonin. Platelets release serotonin at sites of vascular injury, which signals vasoconstriction and amplification of platelet aggregation for hemostatic thrombus formation.Citation6 However, platelets accumulate serotonin via transporters.Citation7 Treatment with therapeutic doses of serotonin-modulating agents blocks these transporters,Citation8 ultimately impairing serotonin accumulation and thereby rendering platelets dysfunctional.

Duloxetine (Cymbalta®; Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) is an SNRI that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder and the management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain. Outside of the United States, it is also approved for lower urinary tract disorders in some countries. A safety profile of duloxetine across these indications has been published that analyzed rates of common treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) (defined as AEs that were experienced by 5% or more of duloxetine-treated patients) comparing duloxetine with placebo.Citation9 In those analyses, the frequency of any single bleeding-related event did not meet the threshold for being classified as a common TEAE. The objective of the current analyses was to gain a better understanding of the risk of bleeding-related TEAEs associated with duloxetine treatment in patients who used concomitant NSAIDs. We analyzed the incidence of these TEAEs from placebo-controlled trials of duloxetine across indications. In addition, we analyzed the incidence of these events reported in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), which receives reports from health care professionals, consumers, and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Methods

Characteristics of included studies

Safety data were pooled from all randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of duloxetine conducted between December 1993 and December 2010. All studies were conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. National or institutional review boards at each study site approved the protocols, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to entrance into a study. All patients were at least 18 years of age or older. The acute treatment phase duration of most studies was 3 months or less, and duloxetine doses ranged between 5 mg/day and 120 mg/day. Dosing schedules were fixed or flexible, and the majority of patients received 60 mg/day, 80 mg/day, or 120 mg/day. For all analyses apart from those examining the effect of dosing on bleeding outcomes, duloxetine dose groups were pooled.

Analysis of clinical trial data

Bleeding-related TEAEs were those events that newly occurred or worsened during the treatment phase as compared to the pre-randomization period. These events were coded into a preferred term using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)Citation10 version 12.0, which could then be searched using preferred terms from the Standardized MedDRA Queries (SMQs [version 12.0]),Citation11 that included hemorrhage non-laboratory terms (SMQ20000039) and hemorrhage laboratory terms (SMQ20000040). GI bleeding-related TEAEs were searched using specific GI bleeding-related preferred terms.

During each clinical trial, NSAID (including aspirin) use was recorded on electronic case report forms. The information on these forms lacked consistent comprehensive dose and/or duration of use, so concomitant NSAID use was defined as taking an NSAID at any time during the treatment phase. Patients in both treatment groups were then categorized as an NSAID user or non-user.

Differences in the incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs between NSAID subgroups (user versus non-user) were analyzed by a logistic regression model that included therapy, NSAID use, and therapy-by-NSAID subgroup interaction. A statistically significant treatment-by-NSAID subgroup interaction was defined as P≤0.1. Within-subgroup group comparisons were conducted using Fisher’s exact test and were significant at P≤0.05.

To determine whether higher duloxetine doses were associated with an increased incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs, and also to assess if use of NSAIDs modify the dose effect of duloxetine, if such an effect exists, the 55 clinical trials were searched to identify fixed-dose studies with at least two fixed doses of duloxetine in the same study, allowing a direct comparison of two fixed-dose groups. Eight placebo-controlled clinical trials including fixed duloxetine doses of 60 mg, 120 mg, and placebo were found and analyzed. To examine for the presence or absence of a dose effect of duloxetine on the incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs, duloxetine 60 mg and 120 mg were compared with the Cochran–Mantel– Haenszel test for general association controlling for study. Furthermore, to evaluate if the use of concomitant NSAIDs modify the dose effect of duloxetine, if such an effect exists, a subgroup analysis was conducted using the same logistic regression model that included therapy, NSAID use, and therapy-by-NSAID subgroup interaction, with the exception that three treatment arms instead of two were examined.

Finally, to examine whether patients were exposed to a higher bleeding risk when taking duloxetine together with an NSAID compared with taking duloxetine on its own, the incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs was compared between NSAID user subgroups within treatment groups using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test controlling for study.

FAERS data analysis

The FAERS database was searched through March 31, 2012 to ascertain whether there was disproportional reporting of bleeding-related TEAEs associated with duloxetine treatment and concomitant NSAID use (including aspirin). Bleeding-related TEAEs were combined into two groups based upon preferred terms SMQ (excluding laboratory terms). Upper GI bleeding events were combined into one preferred-term group, and another preferred-term group contained all other bleeding-related events. Among cases with duloxetine or NSAIDs as either suspected or concomitant drug(s), the following case groups were utilized: duloxetine without NSAIDs (duloxetine) and duloxetine + NSAIDs. A disproportionality analysis based on the empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM)Citation12 was employed to analyze the case groups. The number of cases in the duloxetine group for each group of bleeding-related preferred terms was compared against the full FAERS background, which was comprised of the number of cases reported for each group of preferred terms for drugs other than duloxetine. A similar comparison was made for the number of cases in the duloxetine + NSAIDs group. In addition, the duloxetine + NSAIDs group was compared against the number of cases reported for each group of preferred terms for NSAIDs taken alone. The lower bound of a 90% confidence interval of EBGM (EB05) ≥1 was used as the criterion to signify that the disproportionality of the number of cases reported were higher than in the comparison groups.

Results

Placebo-controlled trials

A total of 19,529 patients (duloxetine, N=11,305; placebo, N=8,224) participated in 55 studies across duloxetine indications that included five studies in chronic musculoskeletal pain (three in chronic low back painCitation13–Citation15 and two in osteoarthritis knee painCitation16,Citation17); four in diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain;Citation18–Citation21 five in fibromyalgia;Citation22–Citation26 four in generalized anxiety disorder;Citation27–Citation30 20 in lower urinary tract disorder;Citation31–Citation44 and 17 in major depressive disorder.Citation45–Citation57 Across these trials among NSAID users, 2,580 received placebo and 3,357 received duloxetine; among NSAID non-users, 5,644 received placebo and 7,948 received duloxetine.

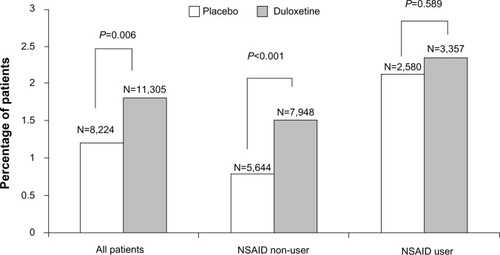

Bleeding-related TEAEs, including GI bleeding-related events, are summarized in . Overall, the proportion of duloxetine-treated patients experiencing at least one bleeding-related TEAE was significantly greater than that in placebo-treated patients (1.8% versus [vs] 1.2%; P=0.006).

Table 1 Bleeding-related treatment-emergent adverse events that occurred in five or more duloxetine-treated patients overall and across NSAID user subgroups

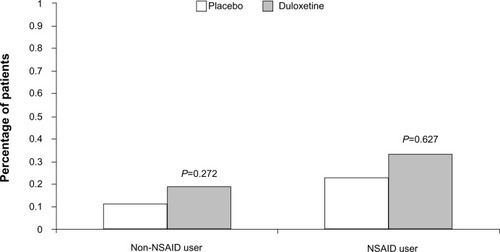

There was a significant treatment-by-NSAID-use subgroup interaction for the occurrence of at least one bleeding event (P=0.029), with a statistically significant duloxetine/placebo difference of 0.71% (1.51% vs 0.80%) in the NSAID non-user group as compared to a nonsignificant 0.22% difference (2.35% vs 2.13%) in the NSAID user group (). This indicates the presence of a smaller duloxetine/placebo difference in patients taking concomitant NSAIDs compared with patients not taking NSAIDs. A significant treatment-by-subgroup interaction was not seen for the group of GI bleeding-related events, with a nonsignificant duloxetine/placebo difference of 0.08% (0.19% vs 0.11%) seen in the NSAID non-user group and a nonsignificant 0.10% duloxetine/placebo difference (0.33% vs 0.23%) seen in the NSAID user group ().

Figure 1 Percentage of patients in the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) user/non-user subgroups that reported any treatment-emergent bleeding-related adverse event during placebo-controlled trials of duloxetine.

Figure 2 Percentage of patients in the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) user/non-user subgroups that reported treatment-emergent gastrointestinal bleeding-related adverse event during placebo-controlled trials of duloxetine.

The dose analyses included eight fixed-dose studies across different disease states; within these studies, 930 patients were randomized to placebo, 913 to duloxetine 60 mg/day, and 904 to duloxetine 120 mg/day. Comparison of the incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs in patients treated with duloxetine 60 mg compared with duloxetine 120 mg revealed no statistically significant differences between the two dose groups for all-bleeding-related TEAEs combined or GI bleeding-related events only. For all-bleeding-related TEAEs combined, there was no statistically significant dose-by-NSAID interaction, indicating that use of NSAIDs did not modify the effect of duloxetine dose. For GI bleeding-related events, a dose-by-NSAID interaction could not be calculated because there were no events reported in at least one treatment arm in each of the NSAID user subgroups.

To examine whether patients were exposed to a higher bleeding risk when taking duloxetine together with an NSAID compared with taking duloxetine on its own, statistical comparisons were conducted for the comparison of duloxetine + NSAID versus duloxetine alone, as well as the comparison of placebo + NSAID versus placebo alone. Regarding all bleeding-related TEAEs, 2.35% of duloxetine-treated patients who used concomitant NSAIDs experienced a bleeding-related event versus 1.51% of duloxetine-treated patients who did not take an NSAID (P<0.044), while 2.13% of placebo-treated patients who also took an NSAID experienced a bleeding-related event versus 0.8% of patients treated with placebo alone. The incidence of GI bleeding-related events within treatment groups was not statistically significantly greater for NSAID users compared with non-users. In duloxetine-treated patients, 0.33% of NSAID users versus 0.19% of NSAID non-users (P=0.536) experienced a GI bleeding-related event, and in placebo-treated patients, 0.23% of NSAID users versus 0.11% of NSAID non-users (P=0.488) experienced a GI bleeding-related event.

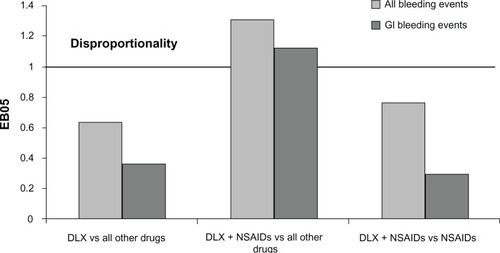

FAERS

Cases for the all-bleeding-related TEAEs and upper GI bleeding-related TEAEs are summarized in . The results of the disproportionality analysis for these events are shown in and . None of the bleeding events, including upper GI bleeding events, were disproportionally reported for duloxetine monotherapy when compared against the full FAERS background that included cases for all other drugs. The reporting of the all-bleeding-related events group (EB05=1.31) and the upper GI bleeding group (EB05=1.12) was more frequent in the cases reported for duloxetine taken with NSAIDs than in the cases reported for drugs other than duloxetine. However, there was no difference in reporting of either group of events when the cases reported for duloxetine taken with NSAIDs were compared against the cases reported for NSAIDs without duloxetine.

Figure 3 FAERS relative reporting of gastrointestinal bleeding events in patients taking duloxetine versus (vs) those not taking duloxetine.

Table 2 Bleeding events from the FAERS up to March 31, 2012 and the results of disproportionality analysis

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate GI and other bleeding-related TEAEs that may be associated with a single SNRI, duloxetine, when taken concomitantly with, and without, NSAIDs. Previous studies have reported on serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a class (SSRIs or SNRIs or both classes combined)Citation5,Citation58–Citation62 without regard to individual differences among these medications with respect to their affinity for the serotonin reuptake receptor, which may affect the level of risk for bleeding-related TEAEs when taken alone or in combination with NSAIDs.Citation63,Citation64

Consistent with duloxetine’s mechanism of action, more duloxetine-treated patients in clinical trials experienced a bleeding-related AE compared with placebo-treated patients. A significantly greater risk of bleeding-related events was seen among duloxetine- versus placebo-treated clinical trial patients who did not use NSAIDs; interestingly, however, while rates of bleeding-related TEAEs were higher in both the duloxetine and placebo treatment groups in patients who also took concomitant NSAIDs, the duloxetine/placebo difference in these rates was smaller than that in the NSAID non-user group and not statistically significant. We hypothesize that the bleeding risk associated with NSAID treatment is greater than that of duloxetine alone, thereby diluting the duloxetine/placebo difference when duloxetine is combined with NSAIDs. These results do not indicate that the combination of duloxetine and NSAIDs significantly increases the bleeding risk beyond the individual risks of each agent.

There was no statistically significant difference between the duloxetine 60 mg and 120 mg doses with respect to the incidence of either all-bleeding-related events or GI bleeding-related events. While this suggests that the use of higher doses of duloxetine is not associated with an increased risk of bleeding events, the results should be interpreted with caution, as relatively few patients were included in the analyses due to the need to include studies with at least two fixed duloxetine-dose arms and a placebo control. There were no duloxetine dose-by-NSAIDs interactions to suggest that the use of concomitant NSAIDs might influence the effect of duloxetine dose.

To address the question of whether patients are exposed to a higher bleeding risk when taking duloxetine together with NSAIDs compared to taking duloxetine alone, between-subgroup comparisons were conducted within treatment groups. The combination of duloxetine and NSAIDs was associated with a statistically significantly higher incidence rate of all bleeding TEAEs compared with duloxetine alone, suggesting an increased risk of bleeding with the combination. Given the well-known risks of bleeding associated with NSAIDs, the finding of a greater incidence of bleeding events for the combination of duloxetine and an NSAID compared with duloxetine alone seems unsurprising. It must, however, be remembered that patients were not randomly assigned to take duloxetine plus NSAIDs or duloxetine alone, so the finding should be treated with caution due to the potential for selection bias.

The results of the disproportionality analysis of bleeding events reported in the FAERS were not significant based on a conservative threshold of EB05 ≥1.0 when duloxetine cases, without NSAIDs as suspected or concomitant drugs, were compared with cases reported for all other drugs. Disproportional reporting was found when duloxetine cases with NSAIDs as suspected or concomitant drugs were compared to cases reported for all other drugs, excluding duloxetine and NSAIDs. However, the disproportionality of reporting for these events disappeared when compared to cases reported for NSAIDs taken alone, suggesting that the finding was driven by concomitant NSAID use rather than by duloxetine. These results are supported by other researchers who did not find an increased risk for bleeding events when NSAIDs were taken with SSRIs, especially when compared to the risk of taking NSAIDs alone.Citation64,Citation65

There are limitations to the analyses of placebo-controlled data. First, the clinical trial data are limited by incomplete information regarding dosing and frequency of concomitant NSAID use. Because of this challenge, we were unable to discern whether patients were taking a therapeutic dose every day or less frequently during the study. Based on what is known about the risk factors for bleeding events, these scenarios could have very different risks. The short duration of most of these studies may also limit the occurrence and detection of bleeding events that develop with prolonged concomitant NSAID use. Regarding the dose analyses, the results should be interpreted with caution – relatively few patients were included in the analyses due to the need to include studies with at least two fixed duloxetine-dose arms and a placebo control.

It is also important to understand the limitations of analyses based on the FAERS data. The rate of spontaneous reporting of any selected TEAE may not reflect the true incidence of that event in the population due to recognized underreporting of these events. In addition, the analyses based on spontaneous datasets like the FAERS are also hampered by duplicate case listings and a large number of false-positive results.

Conclusion

Duloxetine-treated patients in clinical trials had a higher incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs compared with placebo-treated patients, although the duloxetine/placebo difference was smaller in patients using concomitant NSAIDs than it was in non-NSAID users; concomitant use of NSAIDs was associated with a higher incidence of bleeding-related TEAEs in clinical trial patients regardless of whether they were taking duloxetine or placebo. Use of a higher (120 mg once daily) dose of duloxetine was not associated with a higher incidence of bleeding-related events than a lower (60 mg once daily) dose, regardless of concomitant NSAID use; the dose analyses should, however, be treated with caution due to the small sample size. The combination of duloxetine and NSAIDs was associated with a statistically significantly higher incidence rate of all bleeding TEAEs compared with duloxetine alone, suggesting an increased risk of bleeding with the combination. In spontaneously reported post-marketing data, duloxetine and concurrent NSAID use was not associated with significant disproportional reporting of bleeding events when compared with NSAID use alone.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Company, India-napolis, IN, USA. The studies included in the analyses were sponsored and/or supported by Eli Lilly and Company and Boehringer Ingelheim, GmbH.

Disclosure

All authors own stock in and are employees of Eli Lilly and Company or a subsidiary. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GoldbergRJSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: infrequent medical adverse effectsArch Fam Med19987178849443704

- AndradeCSandarshSChethanKBNageshaKSSerotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanismsJ Clin Psychiatry201071121565157521190637

- MacDonaldTMMorantSVRobinsonGCAssociation of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with continued exposure: cohort studyBMJ19973157119133313379402773

- SalvoFFourrier-RéglatABazinFInvestigators of Safety of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: SOS ProjectCardiovascular and gastrointestinal safety of NSAIDs: a systematic review of meta-analyses of randomized clinical trialsClin Pharmacol Ther201189685586621471964

- DaltonSOJohansenCMellemkjærLNørgårdBSørensenHTOlsenJHUse of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding: a population-based cohort studyArch Intern Med20031631596412523917

- De ClerckFThe role of serotonin in thrombogenesisClin Physiol Biochem19908Suppl 340491966729

- LeschKPWolozinBLMurphyDLReidererPPrimary structure of the human platelet serotonin uptake site: identity with the brain serotonin transporterJ Neurochem1993606231923227684072

- SalleeFRHilalRDoughertyDBeachKNesbittLPlatelet serotonin transporter in depressed children and adolescents: 3H-paroxetine platelet binding before and after sertralineJ Am Aad Child Adolesc Psychiatry1998377777784

- BruntonSWangFEdwardsSBProfile of adverse events with duloxetine treatment: a pooled analysis of placebo-controlled studiesDrug Saf201033539340720397739

- BrownEGWoodLWoodSThe medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA)Drug Saf1999220210911710082069

- MozzicatoPStandardised MedDRA queries: their role in signal detectionDrug Saf200730761761917604415

- SzarfmanAMachadoSGO’NeillRTUse of screening algorithms and computer systems to efficiently signal higher-than-expected combinations of drugs and events in the US FDA’s spontaneous reports databaseDrug Saf200225638139212071774

- SkljarevskiVDesaiahDLiu-SeifertHEfficacy and safety of duloxetine in patients with chronic low back painSpine (Phila Pa 1976)20103513E578E58520461028

- SkljarevskiVOssannaMLiu-SeifertHA double-blind, randomized trial of duloxetine versus placebo in the management of chronic low back painEur J Neurol20091691041104819469829

- SkljarevskiVZhangSDesaiahDDuloxetine versus placebo in patients with chronic low back pain: a 12-week, fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind trialJ Pain201011121282129020472510

- ChappellASOssannaMJLiu-SeifertHDuloxetine, a centrally acting analgesic, in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: a 13-week, randomized, controlled trialPain2009146325326019625125

- ChappellASDesaiahDLiu-SeifertHA double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of duloxetine for the treatment of chronic pain due to osteoarthritis of the kneePain Pract2011111334120602715

- GoldsteinDJLuYDetkeMJLeeTCIyengarSDuloxetine vs placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathyPain20051161–210911815927394

- WernickeJFPritchettYLD’SouzaDNA randomized controlled trial of duloxetine in diabetic peripheral neuropathic painNeurology20066781411142017060567

- RaskinJPritchettYLWangFA double-blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic painPain Med20056534635616266355

- GaoYNingGJiaWPDuloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of patients with diabetic neuropathic pain in ChinaChin Med J (Engl)2010123223184319221163113

- ArnoldLMLuYCroffordLJA double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorderArthritis Rheum20045092974298415457467

- ArnoldLMRosenAPritchettYLA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorderPain20051191–351516298061

- RussellIJMeasePJSmithTREfficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder: results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trialPain2008136343244418395345

- ChappellASBradleyLAWiltseCDetkeMJD’SouzaDNSpaethMA six-month double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgiaInt J Gen Med200819110220428412

- ArnoldLMClauwDJWangFFlexible-dosed duloxetine in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Rheumatol201037122578258620843911

- KoponenHAllgulanderCEricksonJEfficacy of duloxetine for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: implications for primary care physiciansPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry20079210010717607331

- HartfordJKorsteinSLiebowitzMDuloxetine as an SNRI treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: results from a placebo and active-controlled trialInt Clin Psychopharmacol200722316717417414743

- RynnMRussellJEricksonJEfficacy and safety of duloxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a flexible-dose, progressive-titration, placebo-controlled trialDepress Anxiety200825318218917311303

- NicoliniHBakishDDuenasHImprovement of psychic and somatic symptoms in adult patients with generalized anxiety disorder: examination from a duloxetine, venlafaxine extended-release and placebo-controlled trialPsychol Med200939226727618485261

- NortonPAZinnerNRYalcinIBumpRCDuloxetine Urinary Incontinence Study GroupDuloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinenceAm J Obstet Gynecol20021871404812114886

- GhoniemGMVan LeeuwenJSElserDMDuloxetine/Pelvic Floor Muscle Training Clinical Trial GroupA randomized controlled trial of duloxetine alone, pelvic floor muscle training alone, combined treatment and no active treatment in women with stress urinary incontinenceJ Urol200517351647165315821528

- CardozoLDrutzHPBayganiSKBumpRCPharmacological treatment for women awaiting surgery for stress urinary incontinenceObstet Gynecol2004104351151915339761

- van KerrebroeckPAbramsPLangeRDuloxetine Urinary Incontinence Study GroupDuloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of European and Canadian women with stress urinary incontinenceBJOG2004111324925714961887

- DmochowskiRRMiklosJRNortonPAZinnerRNYalcinIBumpRCDuloxetine Urinary Incontinence Study GroupDuloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of North American women with stress urinary incontinenceJ Urol20031704 Pt 11259126314501737

- MillardRJMooreKRenckenRYalcinIBumpRCDuloxetine UI Study GroupDuloxetine vs placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a four-continent randomized clinical trialBJU Int200493331131814764128

- KinchenKSObenchainRSwindleRDuloxetine OAB Study GroupImpact of duloxetine on quality of life for women with symptoms of urinary incontinenceInt Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct200516533734415662490

- SteersWDHerschornSKredertKJDuloxetine OAB Study GroupDuloxetine compared with placebo for treating women with symptoms of overactive bladderBJU Int2007100233734517511767

- BentAEGousseAEHendrixSLDuloxetine compared with placebo for the treatment of women with mixed urinary incontinenceNeurourol Urodyn200827321222117580357

- Castro-DiazDPalmaPCBouchardCDuloxetine Dose Escalation Study GroupEffect of dose escalation on the tolerability and efficacy of duloxetine in the treatment of women with stress urinary incontinenceInt Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct200718891992917160693

- LinATSunMJTaiHLDuloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of women with stress predominant urinary incontinence in Taiwan: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trialBMC Urol20088218221532

- MahSYLeeKSChooMSDuloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of Korean women with stress predominant urinary incontinenceKorean J Urol200647527535

- CardozoLLangeRVossSShort- and long-term efficacy and safety of duloxetine in women with predominant stress urinary incontinenceCurr Med Res Opin201026225326119929591

- Schagen van LeeuwenJHLangeRRJonassonAFChenWJViktrupLEfficacy and safety of duloxetine in elderly women with stress urinary incontinence or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinenceMaturitas200860213814718547757

- GoldsteinDJMallinckrodtCLuYDemitrackMADuloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a double-blind clinical trialJ Clin Psychiatry200263322523111926722

- NemeroffCBSchatzbergAFGoldsteinDJDuloxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorderPsychopharmacol Bull200236410613212858150

- GoldsteinDJLuYDetkeMJWiltseCMallinckrodrCDemitrackMADuloxetine in the treatment of depression: a double-blind placebo-controlled comparison with paroxetineJ Clin Psychopharmacol200424438939915232330

- DetkeMJWiltseCGMallinckrodtCHMcNamaraRKDemitrackMABitterIDuloxetine in the acute and long-term treatment of major depressive disorder: a placebo- and paroxetine-controlled trialEur Neuropsychopharmacol200414645747015589385

- PerahiaDGSWangFMallinckrodtCHWalkerDJDetkeMJDuloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a placebo- and paroxetine-controlled trialEur Psychiatry200621636737816697153

- DetkeMJLuYGoldsteinDJHayesJRDemitrackMADuloxetine, 60 mg once daily for major depressive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trialJ Clin Psychiatry200263430831512000204

- DetkeMJLuYGoldsteinDJMcNamaraRKDemitrackMADuloxetine 60 mg once daily dosing versus placebo in the acute treatment of major depressionJ Psychiatr Res200236638339012393307

- RaskinJWiltseCGSiegalAEfficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialAm J Psychiatry2007164690090917541049

- BrannanSKMallinckrodtCHBrownEBWohlreichMMWatkinJGSchatzbergAFDuloxetine 60 mg once-daily in the treatment of painful physical symptoms in patients with major depressive disorderJ Psychiatr Res2005391435315504423

- NierenbergAAGreistJHMallinckrodtCHDuloxetine versus escitalopram and placebo in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder: onset of antidepressant action, a non-inferiority studyCurr Med Res Opin200723240141617288694

- BrechtSCourtecuisseCDebieuvreCEfficacy and safety of duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of pain in patients with major depressive disorder and at least moderate pain of unknown etiology: a randomized controlled trialJ Clin Psychiatry200768111707171618052564

- OakesTMMyersALMarangellLBAssessment of depressive symptoms and functional outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder treated with duloxetine versus placebo: primary outcomes from two trials conducted under the same protocolHum Psychopharmacol2012271475622241678

- MundtJCDebrotaDJGreistJHAnchoring perceptions of clinical change on accurate recollection of the past: memory enhanced retrospective evaluation of treatment (MERET)Psychiatry (Edgmont)200743394520805909

- de AbajoFJRodriguezLAMonteroDAssociation between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and upper gastrointestinal bleeding: population-based case-control studyBMJ199931972171106110910531103

- de JongJCvan den BergPBTobiHde Jong-van den BergLTCombined use of SSRIs and NSAIDs increases the risk of gastrointestinal adverse effectsBr J Clin Pharmacol200355659159512814454

- Helin-SalmivaaraAHuttunenTGrönroosJMKlaukkaTHuupponenRRisk of serious upper gastrointestinal events with concurrent use of NSAIDs and SSRIs: a case-control study in the general populationEur J Clin Pharmacol200763440340817347805

- van WalravenCMamdaniMMWellsPSWilliamsJIInhibition of serotonin reuptake by antidepressants and upper gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly patients: retrospective cohort studyBMJ2001323731465565811566827

- WessingerSKaplanMChoiLIncreased use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in patients admitted with gastrointestinal haemorrhage: a multicentre retrospective analysisAliment Pharmacol Ther200623793794416573796

- LewisJDStromBLLocalioARModerate and high affinity serotonin reuptake inhibitors increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal toxicityPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200817432833518188866

- VidalXIbáñezLVendrellLConfortiALaporteJRSpanish-Italian Collaborative Group for the Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal BleedingRisk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and the degree of serotonin reuptake inhibition by antidepressants: a case-control studyDrug Saf200831215916818217791

- TargownikLEBoltonJMMetgeCJLeungSSareenJSelective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are associated with a modest increase in the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleedingAm J Gastroenterol200910461475148219491861