Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective anti-inflammatory and analgesic agents and are among the most commonly used classes of medications worldwide. However, their use has been associated with potentially serious dose-dependent gastrointestinal (GI) complications such as upper GI bleeding. GI complications resulting from NSAID use are among the most common drug side effects in the United States, due to the widespread use of NSAIDs. The risk of upper GI complications can occur even with short-term NSAID use, and the rate of events is linear over time with continued use. Although gastroprotective therapies are available, they are underused, and patient and physician awareness and recognition of some of the factors influencing the development of NSAID-related upper GI complications are limited. Herein, we present a case report of a patient experiencing a gastric ulcer following NSAID use and examine some of the risk factors and potential strategies for prevention of upper GI mucosal injuries and associated bleeding following NSAID use. These risk factors include advanced age, previous history of GI injury, and concurrent use of medications such as anticoagulants, aspirin, corticosteroids, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Strategies for prevention of GI injuries include anti-secretory agents, gastroprotective agents, alternative NSAID formulations, and nonpharmacologic therapies. Greater awareness of the risk factors and potential therapies for GI complications resulting from NSAID use could help improve outcomes for patients requiring NSAID treatment.

Case study

A 53-year-old otherwise healthy female was admitted to the emergency department following two bouts of hematemesis and a single melenic stool. She denied abdominal pain or discomfort and reported no personal or family history of gastric ulcer. The patient reported being prescribed naproxen 500 mg twice daily for the 2 days prior for an ankle sprain. On examination, the patient was hypotensive in the supine position, with a blood pressure of 90/30 mmHg, and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 130 beats per minute. Abdominal examination was benign without tenderness. Hemoglobin was 10.2 g/dL and hematocrit was 33.4%; all other evaluated laboratory values were within normal limits. Endoscopy revealed a 1×1 cm hemorrhagic gastric ulcer in the antrum with a visible vessel (), which was cauterized at the time of endoscopy. Biopsies of the antrum and body were negative for Helicobacter pylori. Cautery was successful, and the patient was treated with an intravenous proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) and remained hospitalized for observation and to evaluate for rebleeding. During hospitalization, the patient was transitioned to an oral PPI. After 2 days without evidence of rebleeding and with the patient’s vital signs returning to normal, she was discharged home with an oral PPI. Her naproxen was not continued.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and incidence of complications

Prevalence of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use

Adequate pain management is a widespread clinical concern, and both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are frequently used for pain relief.Citation1 NSAID use may also be increasing, as indicated by a 2010 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) that found that 12.8% of adults in the United States were taking NSAIDs at least three times a week for 3 months, representing an increase of over 40% compared with the results of a similar interview in 2005.Citation2 This volume of use and the increase represent substantial concerns, which are compounded by the results of telephone surveys indicating that up to 26% of OTC NSAID users take more than the recommended dose.Citation1,Citation3

NSAID-associated gastrointestinal complications

NSAID use has been associated with cardiovascular (CV), renal, and gastrointestinal (GI) complications, and certain patients are at increased risk. NSAID use results in small but consistent increases in the risk of CV events such as myocardial infarction, affected in part by dose and potency of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibition.Citation4,Citation5 NSAID use has also long been associated with kidney disease,Citation6 resulting in both acute and chronic impairments in kidney function.Citation7 These complications prompted the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to release a scientific statement in 2005 emphasizing “the importance of using the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible if treatment with an NSAID is warranted for an individual patient.”Citation8,Citation9

More common than CV and renal complications associated with NSAID use are NSAID-related GI events, which are among the most common drug-related side effects in the United StatesCitation10,Citation11 and occur in both prescription and OTC NSAID users. These complications include bleeding gastric or duodenal ulcers and, to a lesser extent, obstructions and perforations.Citation12 In a retrospective analysis of a rheumatoid arthritis patient database published in 2000, OTC ibuprofen and naproxen users had a relative risk for serious GI complications of approximately 3.5 compared with NSAID nonusers,Citation13 and it is estimated that 1%–2% of continuous NSAID users experience a clinically significant upper GI event per year.Citation14–Citation18 These findings represent a significant clinical concern, as patients taking NSAIDs experience a relative risk of upper GI bleeding and perforations of up to 4.7 compared with nonusers.Citation19

GI complications are generally thought to be mediated primarily through inhibition of mucosal cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and resultant suppression of prostaglandin production.Citation20 However, COX-2 inhibition and other mechanisms, such as changes in the bacterial microbiome in the gut or the generation of free radicals, are also possibly involved.Citation21,Citation22 There is some question regarding the extent to which differential inhibition of COX-1 and -2 affects the GI risks associated with various NSAIDs. NSAIDs exhibit differential COX-1 and -2 inhibition and have been associated with different risks of GI and CV adverse events that vary among patients,Citation20,Citation23 but data sufficient to justify differences in labeling among NSAIDs in the United States have not been established.Citation24,Citation25

In contrast to the acute effects of NSAIDs on the GI tract, there is some evidence that NSAID use may reduce risks of GI cancers, including gastric, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers.Citation26 For example, several studies have found that nonaspirin NSAID treatments are associated with decreased risk of gastric cancerCitation27,Citation28 and, in the case of celecoxib, increased regression of precancerous gastric lesions compared with placebo.Citation29 However, further study is needed to better characterize these potentially protective effects.

Upper GI complications

It is often noted that potentially serious GI complications commonly develop with no clinical warning symptoms suggestive of ulcers or bleeding. However, although NSAID users report increased frequency of various symptoms including reflux, belching, bloating, and/or nausea compared with nonusers,Citation30 these symptoms do not reliably indicate the presence of significant upper GI mucosal injury,Citation31 which includes ulcers, bleeding, perforation, obstruction, and extensive erosions. A prospective observational study found that bleeding complications occurred without typical ulcer symptoms (epigastric pain or dyspepsia) in up to 80% of affected patients.Citation32 In addition, a meta-analysis of studies performed before 1997 and from 1997–2008 found that, while the overall mortality rate from GI bleeds has fallen since the mid-1990s, NSAID users with upper GI bleeding or perforation exhibit a higher mortality rate from these injuries compared with nonusers with comparable clinical scenarios.Citation33 Endoscopic techniques are frequently used to manage peptic ulcer bleeding, but little research has been done to investigate whether NSAID use impacts the rate of successful hemostasis following endoscopic therapy. A retrospective study of only 76 patients found no association between NSAIDs and failure of endoscopy therapy for the treatment of gastric ulcer-associated bleeding, but the sample size was small.Citation34 Interestingly, a randomized controlled trial of 224 patients who developed ulcer complications following NSAID use found that use of a COX-2 selective NSAID (celecoxib) with no effect on platelet aggregation was associated with a lower risk of recurrent bleeding compared with PPI and nonselective NSAID co-therapy; however, both therapies conferred a significant risk of rebleeding.Citation35 These results led to a recommendation by the American College of Physicians that patients with previous ulcer bleeding who require an NSAID be treated with “the combination of a PPI and a COX-2 inhibitor.”Citation36

Lower GI complications

The rate of lower GI complications resulting from NSAID use has not been as widely documented as that of upper GI damage, but such complications have been recognized for decades.Citation37 These injuries include bleeding in the large and small bowel, strictures of the small bowel, or exacerbation of existing illnesses such as inflammatory bowel disease.Citation38 While the incidence of lower GI injury associated with NSAID use is somewhat lower than that of upper GI injury, results from a 2003 prospective study of rheumatoid arthritis patients found that 0.9% of patients taking naproxen 500 mg twice daily developed serious lower GI complications over a 1-year period,Citation39 and a 2005 retrospective study of health records in Spain found that, while the greater incidence of upper GI events results in more fatalities overall, upper and lower GI events have similar mortality rates.Citation40 Video capsule endoscopy assessment of the small bowel has allowed clinicians to better quantify NSAID-related small intestinal mucosal injury,Citation41 as shown by a study that found that healthy volunteers who received either naproxen 500 mg twice daily and omeprazole 20 mg once daily or celecoxib 200 mg twice daily for 2 weeks exhibited significantly more mucosal breaks compared with those receiving placebo.Citation42 Slow-release diclofenac also resulted in new small intestinal mucosal injury compared with baseline after 7 days of use in almost three-quarters of healthy volunteers assessed via capsule endoscopy.Citation43

It is hypothesized that asymptomatic small bowel mucosal injury may lead to occult blood loss over time, resulting in decreases in hemoglobin levels. Results from the CONDOR (celecoxib versus omeprazole and diclofenac in patients with Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid arthritis) study, which compared celecoxib 200 mg twice daily with diclofenac slow-release 75 mg twice daily plus omeprazole (a PPI) 20 mg once daily in arthritis patients at high risk of upper GI complications, support this concept. In that study, investigators found that, while upper GI events did not differ among treatment groups, use of diclofenac and omeprazole resulted in 3.4% of patients exhibiting a ≥2.0 g/L decrease in hemoglobin over approximately 6 months in the absence of overt bleeding.Citation44,Citation45 This finding suggests that GI blood loss may have been more related to slow occult bleeding.Citation46 Together, these studies suggest that lower bowel injuries should be taken into account when considering the risks of NSAID use and when considering managing long-term risk.

Risks of NSAID-associated GI injuries over time

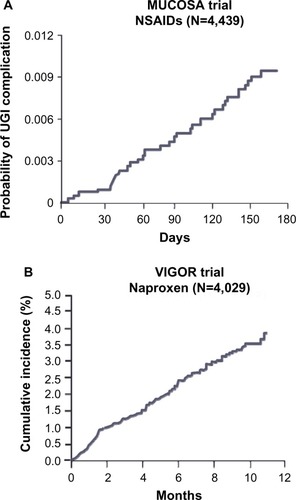

The risk of NSAID-associated GI complications is dose dependent and remains linear over time, based on the results of randomized controlled trials.Citation14,Citation15 The 6-month Misoprostol Ulcer Complication Outcomes Safety Assessment (MUCOSA) study, which investigated the effects of misoprostol coadministration on GI complications associated with NSAID use, and the Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research (VIGOR) study, which compared the GI risks of naproxen with rofecoxib, both found that the cumulative incidence of upper GI events in the nonselective NSAID treatment arms was linear over time ().Citation14,Citation15,Citation47 In addition, two 6-month, double-blind, prospective, randomized clinical trials investigating lower GI injury following NSAID use found that the rate of patients meeting the endpoint of a decrease in hemoglobin >2 g/dL was roughly constant over time.Citation47 Confirming these results in a clinical practice setting was the Gastrointestinal Randomized Event and Safety Open-label Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug Study (GI-REASONS), a randomized, prospective, open-label study comparing celecoxib with nonselective NSAIDs in osteoarthritis (OA) patients, which also found that the cumulative incidence of clinically significant upper and lower GI events was roughly linear over the 6-month trial period.Citation18 Because GI complications associated with NSAID use are dose related and can occur at any time following exposure,Citation32 several international societies, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), have recommended identification of risk factors and prophylaxis independent of the presence or absence of symptoms in patients with moderate-to-high risk of GI complications ().Citation48–Citation50

Figure 2 Incidence of UGI complications with increasing duration of NSAIDs in the MUCOSA and VIGOR trials.

Abbreviations: MUCOSA, Misoprostol Ulcer Complication Outcomes Safety Assessment; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; UGI, upper gastrointestinal; VIGOR, Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients with an elevated risk for NSAID-associated gastrointestinal complications

Risk factors for NSAID-associated GI injury

A variety of patient characteristics are associated with increased risk for NSAID-related GI complications (). Patients with a history of GI injury are at higher risk for GI complications following NSAID use,Citation14,Citation51 and patients with renal failure who are on hemodialysis also exhibit increased risk of GI bleeding with NSAID use.Citation52 Age is an important factor, with risk increasing with increasing age. As the absolute risk varies by age, a threshold of risk based on age is often suggested to be >60 years old.Citation53,Citation54 Patients taking high-dose NSAIDs and those taking NSAIDs with aspirin, even at low, CV-prevention doses (≤325 mg/day), have elevated risks of GI events.Citation55 Certain medications also increase the risk of GI injury when used concurrently with NSAIDs. For example, use of oral corticosteroids coadministered with NSAIDs is associated with an increase in the rate of GI complications as much as twofold compared with patients taking NSAIDs alone.Citation55 Anticoagulants have been found to substantially increase the risk for elderly patients of developing ulcer bleeding when used with NSAIDs.Citation56 Additionally, a Danish study of prescription and hospitalization records of patients ages 16 to 105 years found that anticoagulants and nonsalicylate NSAIDs taken concurrently increased upper GI bleeding more than anticoagulants taken with aspirin or acetaminophen.Citation58 Furthermore, the increased risk of ulcer bleeding due to anticoagulant use may not be mitigated by gastroprotective agents.Citation59 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors also increase risk of upper GI complications when used with NSAIDs, as several studies have shown that concurrent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and NSAID use results in a greater increase in the incidence of GI bleeding than the sum of their independent effects would suggest.Citation61–Citation64 These results suggest that caution should be used when considering prescribing NSAIDs to patients using these agents.

The limited awareness of risk factors results in many patients receiving inadequate preventative therapies. For example, a study of veterans prescribed NSAIDs over a 1-year period showed that nearly three-quarters (73%) of the patients with risk factors for NSAID-related upper GI injury were not receiving appropriate gastroprotective therapy based on evidence-based guidelines.Citation65 In fact, prescription practices may frequently be inappropriate when a patient’s GI and CV history are considered, according to results from a Spanish National Health System study conducted in 2011, which found that 74% of OA patients with elevated risk for GI and CV NSAID-related side effects were receiving nonselective NSAIDs or COX-2 selective NSAIDs.Citation66 These data indicate that not only do NSAIDs represent heightened risks to some patients, but that awareness of the risk factors and of the use of preventative therapy for NSAID-related upper GI injury could be improved.

Approaches to the prevention of GI injuries from NSAIDs

PPIs and histamine-2 (H2) receptor antagonists

Coadministration of NSAIDs with PPIs is a well-documented and effective, although underutilized, approach to reduce endoscopic damage and control dyspeptic symptoms associated with the use of NSAIDs ().Citation65,Citation67–Citation69 Infrequent side effects associated with PPIs have occurred; these may include an increased chance of pneumonia compared with nonusers,Citation12,Citation70 hypomagnesemia,Citation71 and increased incidence of spine and hip fractures,Citation72 as well as an increased chance of contracting Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea compared with PPI-naïve patients.Citation73 H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), which inhibit acid secretion, have also been evaluated for reducing NSAID-associated complications. A meta-analysis of 14 trials found that H2RAs (eg, famotidine and ranitidine) were protective at high doses, but, at commonly prescribed doses, they reduced the risk of duodenal but not gastric ulcers.Citation82 This was demonstrated in a 24-week study of patients requiring chronic NSAID treatment, which showed that coadministration of high-dose (80 mg/day) famotidine with ibuprofen (2,400 mg/day) resulted in significantly fewer gastroduodenal ulcers compared with ibuprofen alone.Citation76 Rare side effects associated with H2RA use include increased risk of pneumonia.Citation68

Table 2 Gastroprotective strategies to prevent gastrointestinal complications associated with NSAID use

Misoprostol

Co-prescribed misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin used to counteract the prostaglandin-inhibitory actions of NSAIDs, decreases NSAID-related upper GI complications by approximately 40% compared with NSAIDs alone.Citation14,Citation83 The single-tablet combination therapy of diclofenac sodium–misoprostol was found to be an effective gastroprotective therapy measured by cost per life-year gained in a study in the Netherlands.Citation84 Of note is that the single-tablet formulation may improve patient adherence, as nonadherence with multiple-pill therapeutic regimens increases the risk of GI events.Citation69,Citation85,Citation86 Unfortunately, misoprostol is not always well tolerated due to diarrhea and abdominal pain, preventing continued use; lower doses of misoprostol with a lesser frequency of side effects may also be less effective at preventing GI events.Citation74 Misoprostol is an abortifacient, contraindicating its use in women who are pregnant or may become pregnant ().Citation75 Rebamipide is a cytoprotective anti-ulcer drug that stimulates prostaglandin production. At a dose of 100 mg three times daily (TID), it was found to be significantly more effective in reducing rates of endoscopic gastric or duodenal ulcer compared with misoprostol 200 mg TID in the Study of NSAID-induced GI Toxicity Prevention by Rebamipide and Misoprostol (STORM), a multicenter, 12-week, randomized controlled trial of patients using NSAIDs. Rebamipide is not approved for use in the United States.Citation87

COX-2 inhibitors

COX-2 selective inhibitors are associated with less risk of GI injury than nonselective NSAIDs due to lesser inhibition of COX-1, which is involved in the maintenance of gastric mucosa integrity. COX-2 selective inhibitor use was associated with a decrease in the risk of symptomatic ulcers and clinically significant ulcer complications compared with nonselective NSAIDs, according to a 2007 meta-analysis.Citation88 In the CONDOR study, while efficacy was similar, fewer patients treated with the COX-2 selective inhibitor celecoxib experienced reductions in hemoglobin or withdrew from the study due to adverse GI events compared with those treated with diclofenac plus omeprazole.Citation44,Citation45 However, use of COX-2 inhibitors at therapeutic doses may increase CV risks.Citation77 Following an FDA warning about the CV risks of COX-2 inhibitors and all nonselective NSAIDs, and the voluntary withdrawals of rofecoxib and valdecoxib from the market,Citation8,Citation89 prescriptions for COX-2 inhibitors decreased by 12% and those for nonselective NSAIDs increased by 47% between 2003 and 2005. However, this trend was not accompanied by an increase in prescriptions of gastroprotective co-therapies.Citation90

Enteric-coated NSAIDs

While at least one study found that enteric-coated NSAIDs reduce upper GI events,Citation91 most data indicate that enteric-coated NSAIDs do not reduce incidence of upper GI events compared with other formulations.Citation92–Citation94 Interestingly, attempts to reduce upper GI symptoms through use of slow-release and enteric-coated formulations may hypothetically increase lower GI complications.Citation95

Topical NSAIDs

Because NSAID-associated GI complications are dose dependent, development of formulations that lower systemic exposure while providing efficacious pain relief may reduce GI injury. Topical NSAID formulations can produce higher concentrations of drug in local tissue with very low systemic exposure as measured via plasma concentrations,Citation96 and use of topical NSAIDs may be associated with fewer GI events ().Citation97–Citation101 Although topical NSAID formulations have been shown to be effective in treatment of acute pain,Citation78 and for short-term use in treating chronic pain, there are conflicting results regarding whether topical NSAIDs provide effective long-term pain relief.Citation102,Citation103 Further study is necessary to determine the long-term benefits and risks of topical NSAID use.

Lower-dose NSAID formulations

New formulations of NSAIDs may reduce risks of adverse events by using lower doses while providing effective analgesia (). There is some evidence that some NSAIDs, such as diclofenac, could provide effective pain relief at lower doses than are currently used, assuming 80% inhibition of COX-2 is necessary for therapeutic efficacy.Citation51 This would hypothetically provide effective pain relief with an improved GI safety profile due to lessened inhibition of COX-1.Citation20

A diclofenac potassium liquid-filled capsuleCitation104 using a formulation designed to deliver diclofenac more rapidly than conventional tablets was approved by the FDA in 2009.Citation105,Citation106 Absorption of the liquid-filled capsules is faster than that of diclofenac potassium immediate-release tablets, and the capsules produce greater pain relief compared with placebo at lower doses of diclofenac (25 mg four times daily) than are generally used;Citation79,Citation105,Citation107 however, it is unclear whether they produce more rapid or effective pain relief than other diclofenac formulations. Lower-dose capsules that contain finely milled, rapidly absorbed NSAID particles may also provide analgesia at lower systemic doses.Citation80,Citation81 Low-dose diclofenac capsules (18 mg or 35 mg TID for mild-to-moderate pain) and indomethacin capsules (20 mg TID or 40 mg two times daily or TID) containing fine-milled particles have been approved by the FDA for treatment of mild-to-moderate acute pain in adultsCitation25,Citation108 and have been found to provide effective relief of acute, postoperative pain in Phase III studies.Citation80,Citation81 Additionally, low-dose diclofenac (35 mg TID) has been shown to provide effective treatment of OA pain in a 12-week study and has been approved by the FDA for management of OA-related pain.Citation109 A low-dose naproxen capsule was also found to effectively relieve postoperative dental pain in a Phase II study.Citation110

H. pylori

Eradicating H. pylori may decrease GI risks in some NSAID users, which could reduce worldwide incidence of NSAID-related GI injury, as H. pylori affects up to 50% of the worldwide population.Citation111 One systematic literature review found that H. pylori eradication in infected patients was as effective as the use of PPIs in preventing GI complications due to NSAID use;Citation57 however, another found that, although H. pylori eradication reduces risk, PPIs provided superior ulcer prevention.Citation112 While it is unclear whether H. pylori eradication is as effective as other strategies, it may provide benefit to some patients.

Nonpharmacologic therapies

Another possibility for reducing the incidence of NSAID-associated GI complications is to reduce NSAID use through adoption of alternative therapies. While assessment of their effectiveness is challenging, therapies such as acupuncture and physical therapy/exercise may provide relief for some patients. While some randomized controlled trials have found acupuncture to be more effective for OA pain relief than sham treatments, a meta-analysis of eleven studies published between 1994 and 2006 found sufficiently heterogeneous results that the authors were unable to draw firm conclusions regarding acupuncture’s efficacy.Citation113 While significant results have been found for use of acupuncture, particularly for knee OA,Citation114 the effect is generally small, and larger studies are needed.Citation115 Exercise and physical therapy may also provide pain relief, as they have been found to improve pain and function in knee OA,Citation116 may delay the need for surgical intervention,Citation117 and may reduce the need for medication.Citation118 Because of these results, the ACR has issued guidelines strongly recommending exercise for knee OA.Citation50 Unfortunately, the effect of exercise on knee OA may be short-term, and the extent of functional improvement is unclear.Citation119 While many approaches for prevention of NSAID-associated GI injury show effectiveness in some studies, practical considerations prevent their universal use.

Cost-effectiveness

The direct cost of preventative strategies to patients and payers and the absolute patient risk for GI complications are the key factors that influence cost-effectiveness. The relative cost of preventing a single complication is high in low-risk populations and is the basis of recommendations from the ACR and other health authorities that indicate that low-risk patients should not receive gastroprotective therapies.Citation49,Citation120,Citation121 The picture becomes more complicated in patients with higher risk for GI injury; as risk increases, the associated costs of prescribing such therapies is increasingly offset by the escalating cumulative costs associated with the adverse events. Net costs/savings are driven by the additional procurement costs of the preventative therapy and the expected frequency of adverse events based on risk.Citation122 Many studies have tried to evaluate cost-effectiveness, but it is difficult to make decisions based on finances given that the cost of PPIs has dramatically declined and that PPIs are now available OTC. Additionally, cost-effectiveness studies do not always adequately take into account the impact of injury on quality of life. An economic model examining PPI use in three large randomized trials, weighted by quality of life, found that use of PPIs with either COX-2 selective inhibitors or nonselective NSAIDs was cost-effective in OA patients, even those at low risk of GI events, with the caveat that the mean age of participants was above 60 years and thus these patients may not be considered to be objectively low risk.Citation123 These studies suggest that the economic picture of how to most cost-effectively decrease NSAID-associated GI injury is not yet clear and that, together, studies considering different risk pools are necessary to determine optimal management of patient subpopulations.

Balancing risks

The CV risks associated with NSAID use have received increased attention recently, such that the American Heart Association released a statement declaring that NSAID use should be “coupled with the realization that effective pain relief may come at the cost of a small but real increase in risk for cardiovascular or cerebrovascular complications.”Citation9 In February 2014, the FDA reviewed the data surrounding the CV complications associated with NSAID use and determined that there were insufficient data to distinguish CV toxicity among individual NSAIDs, including COX-2 selective inhibitors and naproxen, and that this class of agents was associated with an increased risk of ischemic events.Citation25 This attention to the risks associated with NSAIDs and the potential differences among specific NSAIDs represents a growing awareness about the complications associated with this class of drugs.

Conclusion

GI mucosal injury associated with use of NSAIDs is a serious clinical concern, and studies suggest that the rate of complications does not decrease with duration of use. There are several strategies and NSAID drug product formulations that may be associated with decreased GI risk, but there is no one therapy that will provide optimal pain relief and decrease risk for all patients. Also, although nonpharmacological therapies have promise, often they have been inadequately studied compared with pharmacological therapies. Meanwhile, the high cost of GI events to the health care system and to patients’ quality of life necessitates improvement in the risk–benefit profile of NSAIDs or development of alternative medications or therapies. In addition, the CV and renal side effects of NSAIDs must be considered alongside reducing the risk of GI complications. Optimally, developments in pain management will focus on tailoring therapies to the individual patient. Also, in addition to development of new therapies, improvements in patient and provider education and patient adherence are necessary to improve outcomes. Greater awareness of the short-term GI risks of NSAIDs, including potential overuse of OTC NSAIDs and more frequent use of gastroprotection, might have prevented the ulcer in the patient described in the case study at the beginning of this article.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support for this manuscript was provided by Jill See, PhD, and Colville Brown, MD, of AlphaBioCom LLC (King of Prussia, PA, USA). Funding for editorial support was provided by Iroko Pharmaceuticals, LLC (Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Disclosure

JLG has served as an advisory board attendee for Iroko Pharmaceuticals, LLC. BC has served as a consultant for Iroko Pharmaceuticals, LLC; Ritter Pharmaceuticals; Sanofi Pharmaceuticals; Sandoz Pharmaceuticals; and Sucampo, Inc. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WilcoxCMCryerBTriadafilopoulosGPatterns of use and public perception of over-the-counter pain relievers: focus on nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugsJ Rheumatol200532112218222416265706

- ZhouYBoudreauDMFreedmanANTrends in the use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general U.S. populationPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf2014231435023723142

- GoldsteinJLLefkowithJBPublic misunderstanding of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID)-mediated gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity: a serious potential health threatGastroenterology1998114A136

- CaponeMLTacconelliSRodriguezLGPatrignaniPNSAIDs and cardiovascular disease: transducing human pharmacology results into clinical read-outs in the general populationPharmacol Rep201062353053520631418

- García RodríguezLATacconelliSPatrignaniPRole of dose potency in the prediction of risk of myocardial infarction associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general populationJ Am Coll Cardiol200852201628163618992652

- HarirforooshSAsgharWJamaliFAdverse effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update of gastrointestinal, cardiovascular and renal complicationsJ Pharm Pharm Sci201316582184724393558

- ChoudhuryDAhmedZDrug-associated renal dysfunction and injuryNat Clin Pract Nephrol200622809116932399

- Public Health Advisory – FDA Announces Important Changes and Additional Warnings for COX-2 Selective and Non-Selective Non-Steroidal AntiInflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) [webpage on the Internet]Silver Spring, MDUS Food and Drug Administration2005 [updated August 16, 2013; accessed October 10, 2014]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm150314.htmAccessed October 10, 2014

- AntmanEMBennettJSDaughertyAFurbergCRobertsHTaubertKAAmerican Heart AssociationUse of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart AssociationCirculation2007115121634164217325246

- ButtJHBarthelJSMooreRAClinical spectrum of the upper gastrointestinal effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Natural history, symptomatology, and significanceAm J Med1988842A5143279767

- FriesJToward an understanding of NSAID-related adverse events: the contribution of longitudinal dataScand J Rheumatol Suppl1996102388628980

- de JagerCPWeverPCGemenEFProton pump inhibitor therapy predisposes to community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumoniaAliment Pharmacol Ther2012361094194923034135

- SinghGGastrointestinal complications of prescription and over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a view from the ARAMIS database. Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information SystemAm J Ther20007211512111319579

- SilversteinFEGrahamDYSeniorJRMisoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialAnn Intern Med199512342412497611589

- BombardierCLaineLReicinAVIGOR Study GroupComparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study GroupN Engl J Med2000343211520152811087881

- SilversteinFEFaichGGoldsteinJLGastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety StudyJAMA2000284101247125510979111

- LaineLBombardierCHawkeyCJStratifying the risk of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal clinical events: results of a double-blind outcomes study in patients with rheumatoid arthritisGastroenterology200212341006101212360461

- CryerBLiCSimonLSSinghGStillmanMJBergerMFGI-REASONS: a novel 6-month, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint (PROBE) trialAm J Gastroenterol2013108339240023399552

- García RodríguezLAJickHRisk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsLancet199434389007697727907735

- WarnerTDGiulianoFVojnovicIBukasaAMitchellJAVaneJRNonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysisProc Natl Acad Sci U S A199996137563756810377455

- WallaceJLProstaglandins, NSAIDs, and gastric mucosal protection: why doesn’t the stomach digest itself?Physiol Rev20088841547156518923189

- LanasAScarpignatoCMicrobial flora in NSAID-induced intestinal damage: a role for antibiotics?Digestion200673Suppl 113615016498262

- BrunoATacconelliSPatrignaniPVariability in the response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: mechanisms and perspectivesBasic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol20141141566323953622

- Celebrex® (celecoxib) [package insert]New York, NYPfizer2008

- O’RiordanMFDA Advisory Panel Votes Against CV Safety Claim for Naproxen [webpage on the Internet]New York, NYMedscape2014 Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/820470Accessed May 14, 2014

- SahinIHHassanMMGarrettCRImpact of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on gastrointestinal cancers: current state-of-the scienceCancer Lett2014345224925724021750

- LindbladMLagergrenJGarcía RodríguezLANonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancerCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200514244445015734971

- SørensenHTFriisSNørgårdBRisk of cancer in a large cohort of nonaspirin NSAID users: a population-based studyBr J Cancer200388111687169212771981

- WongBCZhangLMaJLEffects of selective COX-2 inhibitor and Helicobacter pylori eradication on precancerous gastric lesionsGut201261681281821917649

- SostresCGargalloCJLanasANonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper and lower gastrointestinal mucosal damageArthritis Res Ther201315Suppl 3S324267289

- ArmstrongCPBlowerALNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and life threatening complications of peptic ulcerationGut19872855275323596334

- SinghGRameyDRMorfeldDShiHHatoumHTFriesJFGastrointestinal tract complications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective observational cohort studyArch Intern Med199615614153015368687261

- StraubeSTramèrMRMooreRADerrySMcQuayHJMortality with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation: effects of time and NSAID useBMC Gastroenterol200994119500343

- SivaRAl ZubaidiGMasoudAKNiharMPredictive factors for failure of endoscopic management therapy in peptic ulcer bleedingSaudi J Gastroenterol200281172119861786

- LaiKCChuKMHuiWMCelecoxib compared with lansoprazole and naproxen to prevent gastrointestinal ulcer complicationsAm J Med2005118111271127816271912

- BarkunANBardouMKuipersEJInternational Consensus Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Conference GroupInternational consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleedingAnn Intern Med2010152210111320083829

- LangmanMJMorganLWorrallAUse of anti-inflammatory drugs by patients admitted with small or large bowel perforations and haemorrhageBr Med J (Clin Res Ed)19852906465347349

- BjorkmanDNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated toxicity of the liver, lower gastrointestinal tract, and esophagusAm J Med19981055A17S21S9855171

- LaineLConnorsLGReicinASerious lower gastrointestinal clinical events with nonselective NSAID or coxib useGastroenterology2003124228829212557133

- LanasAPerez-AisaMAFeuFInvestigators of the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG)A nationwide study of mortality associated with hospital admission due to severe gastrointestinal events and those associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug useAm J Gastroenterol200510081685169316086703

- ChanFKCryerBGoldsteinJLA novel composite endpoint to evaluate the gastrointestinal (GI) effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs through the entire GI tractJ Rheumatol201037116717419884267

- GoldsteinJLEisenGMLewisBGralnekIMZlotnickSFortJGInvestigatorsVideo capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placeboClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20053213314115704047

- MaidenLThjodleifssonBTheodorsAGonzalezJBjarnasonIA quantitative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule enteroscopyGastroenterology200512851172117815887101

- ChanFKLanasAScheimanJBergerMFNguyenHGoldsteinJLCelecoxib versus omeprazole and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (CONDOR): a randomised trialLancet2010376973617317920638563

- KellnerHLLiCEssexMNCelecoxib and diclofenac plus omeprazole are similarly effective in the treatment of arthritis in patients at high GI risk in the CONDOR TrialOpen Rheumatol J201379610024358067

- BowenBYuanYJamesCRashidFHuntRHTime course and pattern of blood loss with ibuprofen treatment in healthy subjectsClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20053111075108216271337

- GoldsteinJLChanFKLanasAHaemoglobin decreases in NSAID users over time: an analysis of two large outcome trialsAliment Pharmacol Ther201134780881621810115

- ConaghanPGDicksonJGrantRLGuideline Development GroupCare and management of osteoarthritis in adults: summary of NICE guidanceBMJ2008336764250250318310005

- LanzaFLChanFKQuigleyEMPractice Parameters Committee of the American College of GastroenterologyGuidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complicationsAm J Gastroenterol2009104372873819240698

- HochbergMCAltmanRDAprilKTAmerican College of RheumatologyAmerican College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and kneeArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201264446547422563589

- Van HeckenASchwartzJIDepréMComparative inhibitory activity of rofecoxib, meloxicam, diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen on COX-2 versus COX-1 in healthy volunteersJ Clin Pharmacol200040101109112011028250

- JankovicSMAleksicJRakovicSNonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and risk of gastrointestinal bleeding among patients on hemodialysisJ Nephrol200922450250719662606

- FriesJFWilliamsCABlochDAMichelBANonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastropathy: incidence and risk factor modelsAm J Med19919132132221892140

- Hernández-DíazSRodríguezLAAssociation between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990sArch Intern Med2000160142093209910904451

- Garcia RodríguezLAHernández-DíazSThe risk of upper gastrointestinal complications associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, acetaminophen, and combinations of these agentsArthritis Res2001329810111178116

- ShorrRIRayWADaughertyJRGriffinMRConcurrent use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral anticoagulants places elderly persons at high risk for hemorrhagic peptic ulcer diseaseArch Intern Med199315314166516708333804

- LeontiadisGISreedharanADorwardSSystematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in acute upper gastrointestinal bleedingHealth Technol Assess20071151iiiiv116418021578

- JohnsenSPSørensenHTMellemkjoerLHospitalisation for upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with use of oral anticoagulantsThromb Haemost200186256356811522004

- LanasAGarcía-RodríguezLAArroyoMTInvestigators of the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG)Effect of anti-secretory drugs and nitrates on the risk of ulcer bleeding associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet agents, and anticoagulantsAm J Gastroenterol2007102350751517338735

- MascleeGMValkhoffVEvan SoestEMCyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or nonselective NSAIDs plus gastroprotective agents: what to prescribe in daily clinical practice?Aliment Pharmacol Ther201338217818923710837

- de AbajoFJRodríguezLAMonteroDAssociation between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and upper gastrointestinal bleeding: population based case-control studyBMJ199931972171106110910531103

- de JongJCvan den BergPBTobiHde Jong-van den BergLTCombined use of SSRIs and NSAIDs increases the risk of gastrointestinal adverse effectsBr J Clin Pharmacol200355659159512814454

- LokeYKTrivediANSinghSMeta-analysis: gastrointestinal bleeding due to interaction between selective serotonin uptake inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsAliment Pharmacol Ther2008271314017919277

- Helin-SalmivaaraAHuttunenTGrönroosJMKlaukkaTHuupponenRRisk of serious upper gastrointestinal events with concurrent use of NSAIDs and SSRIs: a case-control study in the general populationEur J Clin Pharmacol200763440340817347805

- AbrahamNSEl-SeragHBJohnsonMLNational adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the prescription of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugsGastroenterology200512941171117816230071

- LanasAGarcia-TellGArmadaBOteo-AlvaroAPrescription patterns and appropriateness of NSAID therapy according to gastrointestinal risk and cardiovascular history in patients with diagnoses of osteoarthritisBMC Med201193821489310

- SmalleyWSteinCMArbogastPGEisenGRayWAGriffinMUnderutilization of gastroprotective measures in patients receiving nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugsArthritis Rheum20024682195220012209525

- SturkenboomMCBurkeTATangelderMJDielemanJPWaltonSGoldsteinJLAdherence to proton pump inhibitors or H2-receptor antagonists during the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsAliment Pharmacol Ther20031811–121137114714653834

- GoldsteinJLHowardKBWaltonSMMcLaughlinTPKruzikasDTImpact of adherence to concomitant gastroprotective therapy on non-steroidal-related gastroduodenal ulcer complicationsClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20064111337134517088110

- EomCSJeonCYLimJWChoEGParkSMLeeKSUse of acid-suppressive drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysisCMAJ2011183331031921173070

- HessMWHoenderopJGBindelsRJDrenthJPSystematic review: hypomagnesaemia induced by proton pump inhibitionAliment Pharmacol Ther201236540541322762246

- YuEWBauerSRBainPABauerDCProton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of 11 international studiesAm J Med2011124651952621605729

- JanarthananSDitahIAdlerDGEhrinpreisMNClostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and proton pump inhibitor therapy: a meta-analysisAm J Gastroenterol201210771001101022710578

- RostomADubeCWellsGPrevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcersCochrane Database Syst Rev20024CD00229612519573

- TangOSGemzell-DanielssonKHoPCMisoprostol: pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effectsInt J Gynaecol Obstet200799Suppl 2S160S16717963768

- LaineLKivitzAJBelloAEGrahnAYSchiffMHTahaASDouble-blind randomized trials of single-tablet ibuprofen/high-dose famotidine vs. ibuprofen alone for reduction of gastric and duodenal ulcersAm J Gastroenterol2012107337938622186979

- McGettiganPHenryDCardiovascular risk with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review of population-based controlled observational studiesPLoS Med201189e100109821980265

- MasseyTDerrySMooreRAMcQuayHJTopical NSAIDs for acute pain in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev20106CD00740220556778

- LissyMScallionRStiffDDMooreKPharmacokinetic comparison of an oral diclofenac potassium liquid-filled soft gelatin capsule with a diclofenac potassium tabletExpert Opin Pharmacother201011570170820187842

- GibofskyASilbersteinSArgoffCDanielsSJensenSYoungCLLower-dose diclofenac submicron particle capsules provide early and sustained acute patient pain relief in a phase 3 studyPostgrad Med2013125513013824113671

- AltmanRDanielsSYoungCLIndomethacin submicron particle capsules provide effective pain relief in patients with acute pain: a phase 3 studyPhys Sportsmed201341471524231592

- RostomAWellsGTugwellPWelchVDubéCMcGowanJThe prevention of chronic NSAID induced upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a Cochrane collaboration metaanalysis of randomized controlled trialsJ Rheumatol20002792203221410990235

- BocanegraTSWeaverALTindallEADiclofenac/misoprostol compared with diclofenac in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee or hip: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. Arthrotec Osteoarthritis Study GroupJ Rheumatol1998258160216119712107

- AlMJManiadakisNGrijseelsEWJanssenMCosts and effects of various analgesic treatments for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis in the NetherlandsValue Health200811458959918194404

- SturkenboomMCBurkeTADielemanJPTangelderMJLeeFGoldsteinJLUnderutilization of preventive strategies in patients receiving NSAIDsRheumatology (Oxford)200342Suppl 3iii233114585915

- LanasAPolo-TomásMRoncalesPGonzalezMAZapardielJPrescription of and adherence to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastroprotective agents in at-risk gastrointestinal patientsAm J Gastroenterol2012107570771422334248

- ParkSHChoCSLeeOYComparison of prevention of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal complications by rebamipide and misoprostol: a randomized, multicenter, controlled trial-STORM STUDYJ Clin Biochem Nutr200740214815518188417

- RostomAMuirKDubéCGastrointestinal safety of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a Cochrane Collaboration systematic reviewClin Gastroenterol Hepatol200757818828828. e1e517556027

- US Food and Drug AdministrationFDA issues public health advisory on Vioxx as its manufacturer voluntarily withdraws the product [press release]Silver Spring, MDUS Food and Drug Administration2004 [September 30] [updated April 2, 2013; cited October 10, 2014]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2004/ucm108361.htmAccessed October 2, 2014

- GreenbergJDFisherMCKremerJCORRONA InvestigatorsThe COX-2 inhibitor market withdrawals and prescribing patterns by rheumatologists in patients with gastrointestinal and cardiovascular riskClin Exp Rheumatol200927339540119604430

- CaldwellJRRothSHA double blind study comparing the efficacy and safety of enteric coated naproxen to naproxen in the management of NSAID intolerant patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Naproxen EC Study GroupJ Rheumatol19942146896958035394

- Le LoëtXDreiserRLLe GrosVFebvreNTherapeutic equivalence of diclofenac sustained-released 75 mg tablets and diclofenac enteric-coated 50 mg tablets in the treatment of painful osteoarthritisInt J Clin Pract19975163893939489070

- KhongTKDowningMEEllisRPatchettITraynerJMillerAJThe efficacy and tolerability of enteric and non-enteric coated naproxen tablets: a double-blind study in patients with osteoarthritisCurr Med Res Opin19911285405461764957

- BellamyNBeaulieuABombardierCEfficacy and tolerability of enteric-coated naproxen in the treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind comparison with standard naproxen followed by an open-label trialCurr Med Res Opin199212106406511633722

- DaviesNMSustained release and enteric coated NSAIDs: are they really GI safe?J Pharm Pharm Sci19992151410951657

- RolfCEngströmBBeauchardCJacobsLDLe LibouxAIntra-articular absorption and distribution of ketoprofen after topical plaster application and oral intake in 100 patients undergoing knee arthroscopyRheumatology (Oxford)199938656456710402079

- MartensMEfficacy and tolerability of a topical NSAID patch (local action transcutaneous flurbiprofen) and oral diclofenac in the treatment of soft-tissue rheumatismClin Rheumatol199716125319132322

- TugwellPSWellsGAShainhouseJZEquivalence study of a topical diclofenac solution (pennsaid) compared with oral diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trialJ Rheumatol200431102002201215468367

- SimonLSGriersonLMNaseerZBookmanAAZev ShainhouseJEfficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritisPain2009143323824519380203

- BrewerARPierchalaLAYanchickJKMagelliMRovatiSGastrointestinal tolerability of diclofenac epolamine topical patch 1.3%: a pooled analysis of 14 clinical studiesPostgrad Med2011123416817621681001

- PenistonJHGoldMSWiemanMSAlwineLKLong-term tolerability of topical diclofenac sodium 1% gel for osteoarthritis in seniors and patients with comorbiditiesClin Interv Aging2012751752323204844

- LinJZhangWJonesADohertyMEfficacy of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of osteoarthritis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsBMJ2004329746132415286056

- RotherMLavinsBJKneerWLehnhardtKSeidelEJMazgareanuSEfficacy and safety of epicutaneous ketoprofen in Transfersome (IDEA-033) versus oral celecoxib and placebo in osteoarthritis of the knee: multicentre randomised controlled trialAnn Rheum Dis20076691178118317363401

- Zipsor® (diclofenac potassium) [package insert]Newport, KYXanodyne Pharmaceuticals, Inc2009

- DanielsSEBaumDRClarkFGolfMHMcDonnellMEBoesingSEDiclofenac potassium liquid-filled soft gelatin capsules for the treatment of postbunionectomy painCurr Med Res Opin201026102375238420804444

- HershEVLevinLMAdamsonDDose-ranging analgesic study of Prosorb diclofenac potassium in postsurgical dental painClin Ther20042681215122715476903

- KowalskiMStokerDGBonCMooreKABoesingSEA pharmacokinetic analysis of diclofenac potassium soft-gelatin capsule in patients after bunionectomyAm J Ther201017546046819531931

- BelloAEDUEXIS(®) (ibuprofen 800 mg, famotidine 26.6 mg): a new approach to gastroprotection for patients with chronic pain and inflammation who require treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugTher Adv Musculoskelet Dis20124532733923024710

- Zorvolex Highlights of Prescribing Information Available from: https://www.zorvolex.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Zorvolex_Approved_PI.pdfAccessed August 29, 2014

- YoungCLStrandVAltmanRDanielsSA phase 2 study of naproxen submicron particle capsules in patients with post-surgical dental painAdv Ther2013301088589624127200

- CzinnSJHelicobacter pylori infection: detection, investigation, and managementJ Pediatr2005146Suppl 3S21S2615758899

- VergaraMCatalánMGisbertJPCalvetXMeta-analysis: role of Helicobacter pylori eradication in the prevention of peptic ulcer in NSAID usersAliment Pharmacol Ther200521121411141815948807

- ManheimerELindeKLaoLBouterLMBermanBMMeta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the kneeAnn Intern Med20071461286887717577006

- KwonYDPittlerMHErnstEAcupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysisRheumatology (Oxford)200645111331133716936326

- ManheimerEChengKLindeKAcupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritisCochrane Database Syst Rev20101CD00197720091527

- ThomasKSMuirKRDohertyMJonesACO’ReillySCBasseyEJHome based exercise programme for knee pain and knee osteoarthritis: randomised controlled trialBMJ2002325736775212364304

- DeyleGDHendersonNEMatekelRLRyderMGGarberMBAllisonSCEffectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled trialAnn Intern Med2000132317318110651597

- DeyleGDAllisonSCMatekelRLPhysical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures versus a home exercise programPhys Ther200585121301131716305269

- FransenMMcConnellSLand-based exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trialsJ Rheumatol20093661109111719447940

- ScheimanJMThe use of proton pump inhibitors in treating and preventing NSAID-induced mucosal damageArthritis Res Ther201315Suppl 3S524267413

- [No authors listed]Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis GuidelinesArthritis Rheum20004391905191511014340

- RahmeEJosephLKongSXWatsonDJLeLorierJCost of prescribed NSAID-related gastrointestinal adverse events in elderly patientsBr J Clin Pharmacol200152218519211488776

- LatimerNLordJGrantRLO’MahonyRDicksonJConaghanPGNational Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Osteoarthritis Guideline Development GroupCost effectiveness of COX 2 selective inhibitors and traditional NSAIDs alone or in combination with a proton pump inhibitor for people with osteoarthritisBMJ2009339b253819602530