Abstract

Background

Lifestyle Intervention for Weight Loss (LIFE-8) is developed as a structured, group-based weight management program for Emiratis with obesity and type 2 diabetes. It is a 3-month program followed by a 1-year follow-up. The results from the first 2 years are presented here to indicate the possibility of its further adaptation and implementation in this region.

Methodology

We recruited 45 participants with obesity and/or type 2 diabetes based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. The LIFE-8 program was executed by incorporating dietary modification, physical activity, and behavioral therapy, aiming to achieve up to 5% weight loss. The outcomes included body weight, fat mass, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose (FBG), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and nutritional knowledge at 3 months and 12 months.

Results

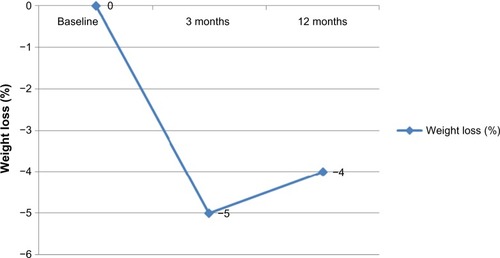

We observed a reduction of 5.0% in body weight (4.8±2.8 kg; 95% CI 3.7–5.8), fat mass (−7.8%, P<0.01), and waist circumference (Δ=4±4 cm, P<0.01) in the completed participants (n=28). An improvement (P<0.05) in HbA1c (7.1%±1.0% vs 6.6%±0.7%) and FBG (8.2±2.0 mmol/L vs 6.8±0.8 mmol/L) was observed in participants with obesity and type 2 diabetes after the program. Increase in nutritional knowledge (<0.01) and overall evaluation of the program (9/10) was favorable. On 1-year follow-up, we found that the participants could sustain weight loss (−4.0%), while obese, type 2 diabetic participants sustained HbA1c (6.6%±0.7% vs 6.4%±0.7%) and further improved (P<0.05) the level of FBG (6.8±0.8 mmol/L vs 6.7±0.4 mmol/L).

Conclusion

LIFE-8 could be an effective, affordable, acceptable, and adaptable lifestyle intervention program for the prevention and management of diabetes in Emiratis. It was successful not only in delivering a modest weight loss but also in improving glycemic control in diabetic participants.

Keywords:

Introduction

Obesity is an important public health problem around the world, and in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) approximately one in every three adults is obese.Citation1 Rapid urbanization leading to lifestyle factors such as overconsumption of calories and decreased physical activity offers a reasonable explanation for this.Citation2 More than 80% individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) are obese, indicating a strong correlation between obesity and T2D.Citation3 Obesity not only impedes the management of T2D by increasing insulin resistance and blood glucose concentration but is also reported to be an independent risk factor associated with dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.Citation4,Citation5 A moderate weight loss of 5% body weight is associated with the prevention of T2D progression in at-risk patients.Citation6 It is also reported to improve insulin action and decrease the fasting blood glucose (FBG) concentrations in patients with T2D.Citation7

Evidence-based guidelines for the management of obesity suggest a multidisciplinary approach, including a combination of diet, physical activity, and behavioral therapy.Citation8 The effectiveness of low-fat, low-energy diets in combination with activity and lifestyle counseling has been demonstrated to result in 5%–10% weight loss and the reduction or prevention of comorbidities such as diabetes and/or hypertension.Citation9 Recent guidelines also recommend group-based interventions in weight management, as they are cost efficient and show increased effectiveness in specific behavior-change strategies.Citation10

Landmark studies such as the Diabetes Prevention Program and Look AHEAD have presented a strong role of lifestyle intervention in the prevention and management of T2D.Citation7,Citation11 One of the most challenging aspects is the implementation of these positive results from clinical trials into usual care due to deficiency of resources and expertise in the area of lifestyle management in this region. Translation of these programs in Arabia is scarce. Ali et al explored the barriers to weight management for Emirati women and suggested the need for culturally acceptable, community-based interventions for the prevention and management of obesity among UAE women.Citation12 A review of the demographic, social welfare, and behavioral variables and overweight prevalence in Arab countries has suggested that Arab women comprise a particularly vulnerable subgroup and the governments should act within religious and cultural parameters to provide environments that are conducive to a negative energy balance.Citation13

We, at the Rashid Centre for Diabetes and Research, aimed at developing a well-conceived, professionally implemented, multidisciplinary, and group-based partial meal replacement/weight management program called Lifestyle Intervention for Weight Loss (LIFE-8). This ongoing program’s overview and results for the first 2 years (October 2012 to December 2014) are presented here to indicate the possibility of its further adaptation and implementation to this region.

Methodology

Program overview

The LIFE-8 program was developed by the Lifestyle Clinic at Rashid Centre for Diabetes and Research, a tertiary care center of diabetes and obesity in Ajman, UAE. Since this paper describes the structure and preliminary results of an evidence based clinical care program, ethical approval was not sought.LIFE-8 was designed to deliver weight loss through lifestyle modification combining diet therapy, physical activity, and behavioral modification. The multidisciplinary team included dietitians, an exercise therapist, a nurse coordinator, and a physician. This weight management program approach has evolved from previous lifestyle programs reported from similar conditions. The goals of this program were adapted on the basis of the available evidence, recommendation, and clinical experience of local dietary patterns of Emiratis.

Our main objective was to assess the weight change after LIFE-8 program; however, the secondary objectives were to assess the changes in fat mass, FBG, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and the knowledge score.

LIFE-8 program was designed to introduce and emphasize the following goals:

Limit cereal intake to 5–7 servings/d.

Increase vegetable intake to 3–4 servings/d.

Achieve physical activity of 7,000 steps/d–10,000 steps/d.

Encourage self-management skills for weight management.

Furthermore, the goals were individualized according to the need of the participant by a registered dietitian. This program was conveyed in eight sessions, ie, five groups and three individual sessions (). Individual sessions were utilized for the initial assessment, individualization of goals, and follow-up. Group sessions were utilized for education and participatory cooking. This program strongly emphasized empowering the participants to make the right choices and adapting to behavioral changes. A structured approach was used for the session execution; core topics were discussed with the help of a standardized presentation. Each session lasted between 60 minutes and 120 minutes with six to ten participants.

Table 1 Contents of each session in the Lifestyle Intervention for Weight Loss (LIFE-8)

Participants

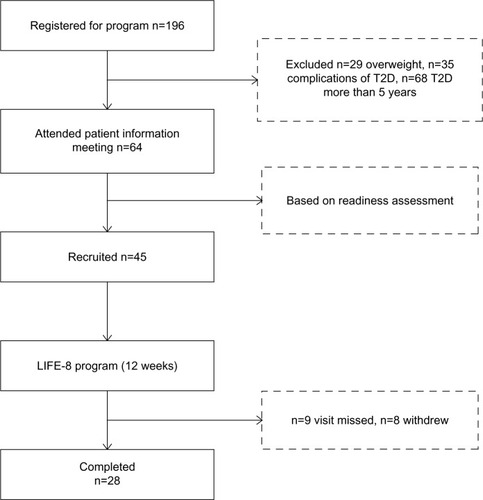

Our program was conducted in the Lifestyle Clinic, an outpatient setting attached to an educational kitchen. Participants were registered through internal referrals and from other health care facilities in the Northern Emirates. The registrants were screened based on the following inclusion–exclusion criteria: men and women of UAE nationality, age between 18 years and 50 years, obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2) or obesity and with T2D (duration of diagnosis ≤5 years), and committed for a 3-month program. Participants were excluded if they had been diagnosed with T2D-associated complications or type 1 diabetes as well as pregnant or lactating women. Although 196 participants registered for this program, only 45 were recruited based on inclusion–exclusion criteria and their readiness to be assessed (). Potential participants attended a group information meeting where the program details were discussed and readiness was assessed by a readiness assessment questionnaire adapted from the American Medical Association (2003),Citation14 which recorded the reason to lose weight, family support interest, and readiness for a lifestyle change.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the program from screening to completion of LIFE-8.

Eligible participants gave written consent of their participation in the program, and an initial nutritional assessment (60 minutes) was done to assess their FBG, HbA1c, blood pressure, body composition, waist circumference, usual dietary intake, and physical activity habits. The program was offered as a part of clinical care program, and there was no cost to the participant.

Dietary intervention

The initial assessment session included dietary recall (usual dietary recall), semistructured food frequency questionnaire, identification of individualized goals, and the handing over of the instructional material (diet plan, goal chart, food log, program schedule) developed by the registered dietitian. The suggested diet plan (1,200–1,500 cal/d) consisted of a combination of conventional balanced diet options as suggested by ADA guidelines and meal replacement as individualized by the dietitian. Two of the three main meals were replaced with a commercial meal replacement (Glucerna SR; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) for 6 weeks, which contributed to 500 cal/d, followed by one meal replacement of 250 cal/d for the following 6 weeks. Participants were advised on an equal calorie meal if they found the meal replacements unpalatable.

Another essential component of the program was group sessions conducted by a registered dietitian. The participants were provided with instructions on healthy eating and diet planning. They were educated on food groups, sources of carbohydrate, portion sizes, cereal exchanges, vegetable portions, ideal plate model, improvisation of local recipes, food labels, and conscious eating.Citation15 Hands-on interactive learning during the healthy cooking sessions was offered by dietitians, which facilitated the learning process by allowing group interaction, engaging discussion, sharing cooking experiences, and the development of improvised healthy local recipes ().

Physical activity intervention

Improving physical activity was a strong focus of the program. All the participants were provided with a pedometer as a mobile tool and could be tracked online by the participant/counselor. A physical therapist provided a structured exercise session twice a week (45 minutes) focusing on aerobic exercises, strength training, and stretching exercises. Participants were encouraged to incorporate moderate-intensity physical activity between 150 minutes/wk and 250 minutes/wk or a step count of 7,000–10,000 per day.Citation16 However, the recommendations were individualized based on the physical fitness and medical condition of the participant.

Behavioral modification intervention

Behavioral therapy helps the participants to make long term, sustainable changes in their eating pattern, physical activity, and control the environmental cues that stimulate eating.Citation17 Food diaries and pedometer activity records were advocated to inculcate the practice of self-monitoring. Additional emphasis was laid on recording the portions of cereals and vegetables. Educational sessions on the identification of appetite, hunger, and environmental cues for trigger eating were discussed as a stimulus control tool. The LIFE-8 program emphasized the need of specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals for weight loss, since goal setting has been reported to encourage the adoption of behavioral change and offer as a tool for self-evaluation.Citation18 Motivational interviewing strategies of empathy, self-efficacy, and rolling with resistance were adapted during the counseling sessions ().

Participant educational material

Educational material was developed on the topics discussed during the sessions to support and reinforce the information. Diet diaries, goal charts, tips on the identification of environmental cues, physical activity, and healthy traditional recipes were made available for the participants.

Outcome measures

A pretested questionnaire was used to collect sociodemographic data, duration of diabetes, other medical conditions, and the history of weight loss. The outcomes were measured at 3 months on completion of the program. Nutritional knowledge was assessed by a pretested questionnaire before and after the program. Anthropometric measurements of height, weight, waist circumference, and body composition were taken with participants wearing light clothing and without shoes by the same person. Body weight and height were recorded using an electronic balance with stadiometer (SECA, Germany) to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. Body composition was assessed by bioelectric impedance using an InBody-230 instrument (Biospace, Dogok-dong, South Korea) under standardized conditions. The BMI (calculated as weight [kg]/heightCitation2 [m2]) was also estimated.

Statistical analysis

All the data were subjected to descriptive analysis, normal distribution was confirmed by histogram plots, and the data were presented as mean ± SD. Differences between pre-and postintervention data were assessed using paired t-test. Primary analysis was conducted similar to the intention to treat for all recruited participants as well as for program completers. Inferences for comparison were tested at the 5% level of significance. All analyses were carried out with the Stata Statistical Software: Release 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Screening of participants, enrollment, and the follow-up sequence are shown in , while the baseline characteristics are described in . The participants were divided based on obesity versus obesity with T2D, and no significant difference was recorded between these subgroups at baseline. Eighty-four percent of participants were reasonably educated, and the purpose of seeking the weight loss program was largely to improve health and the quality of life in both subgroups. Ninety-eight percent of total participants tried to lose weight through dietary restriction and exercises, with no success in weight maintenance.

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of participants at baseline

presents the changes in measures of body weight, fat mass, FBG, and HbA1c during the LIFE-8 program. On analyzing the data for completers (n=28), we found a significant (P<0.01) weight loss of 4.8±2.8 kg (5.0%) (95% CI 3.7–5.8), fat loss 3.8±3.0 kg (7.8%) (95% CI 2.6–5.1), and reduction in waist circumference 4±4 cm (95% CI 1.8–5.6) after the 3-month program. On comparing the two subgroups, we observed that both showed a significant (P<0.01) reduction in body weight, BMI, and fat mass. A significant improvement (P<0.01) in glycemic control (HbA1c and FBG) was observed in participants with obesity and T2D.

Table 3 Effect of LIFE-8 program on anthropometric parameters and glycemic control in completers

After 1-year follow-up of the completers (n=28), we found that they could maintain 4.0% weight loss (<0.001) compared to baseline (). Participants with type 2 diabetes (n=9) showed a sustained glycemic control after 12 months with FBG ().

Table 4 Effect of LIFE-8 on the glycemic control of type 2 diabetic participants (n=9)

Participant feedback

Since evaluation and feedback are the key to learn and improve, all the participants were encouraged to fill a standardized knowledge questionnaire before and after the program, the purpose of which was to study the changes in the nutritional knowledge, ie, self-monitoring, portion control, appetite control, common mistakes occurring during dietary intervention, food exchanges, ideal plate, food labeling, healthy cooking, and myths about weight loss. The average score had increased from 4/10 to 7/10 after the program (P<0.01). The sessions on weight maintenance, healthy cooking, and food labeling scored the highest. Visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 10 measured the overall acceptance of the program and was observed as 9/10. The cost of the program to the clinic was ~US$160 per participant. However, this excluded the cost of meal replacements and the pedometer.

Discussion

These results indicate that the LIFE-8 program was successful in translating evidence-based guidelines for weight management in clinical practice in the UAE. The outcome of this program encourages us to appreciate its benefits not only for contributing to weight loss and fat loss but also in improving the glycemic control inT2D participants.

This program was offered to participants with obesity and T2D after a thorough screening process based on the inclusion–exclusion criteria and readiness assessment. As reported earlier, assessing the readiness to change not only adds an extra step in facilitating the weight loss process but also indicates patient compliance.Citation19–Citation21 Although the program was developed and open for registration for both sex, very few male participants were registered, inadequate to form a group of 6–8. We observed that women seemed to more enthusiastic about participation unlike men, which could be due to the time demanded for this program, as it was offered during morning time on working days. Men were unable to confirm their attendance to the educational sessions at the clinic. The participants were divided into homogenous groups based on their age, educational level, and medical condition. The educational material and the teaching techniques varied marginally based on the conception of the participants in each group. The LIFE-8 program could deliver an average weight loss of 4.8±2.8 (5.0%) (program completers, n=28) and 3.2±2.8 (3.2%) (recruited, n=45). This weight loss was comparable to the average weight loss reported in the systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studies applying the findings of the Diabetes Prevention Program across diverse settings and population, which showed a 4%–5% weight loss that was maintained for a follow-up period of 9 months.Citation22 The weight loss was reflective of decreased (P<0.01) fat mass and waist circumference in the participants (7.8% and 3.7%). These observations are in consonance with the results of a meta-analysis of 56 studies in class II and III obese individuals showing that lifestyle interventions incorporating physical activity improved not only weight loss but also various cardiometabolic risk factors.Citation23 A significant improvement in the glycemic control was not only observed in the subgroup of participants with obesity and T2D () but also in a small subgroup (n=6) with obesity and prediabetes, showing a substantial improvement (P=0.04) in HbA1c after the 3-month program (5.8% vs 5.5%). This could be attributed to clinically relevant health benefits of weight loss on glucose metabolism.Citation24

This program could deliver equally effective results in eight sessions compared to programs offering more than eight sessions (~4%) as described in a meta-analysis.Citation22 Although a few studies have reported that the magnitude of weight loss is related to the number and frequency of sessions,Citation25,Citation26 some have shown that programs of longer duration result in a higher dropout rate.Citation27 Although we could not refer similar programs in the Emirates, a 12-month intensive intervention in Arab women in this region has reported decrease of 2.4±0.4 kg body weight, which is comparable to the results of this program.Citation28 One of the major reasons for not having “translated” lifestyle intervention programs into routine clinical practice is the cost incurred. Nevertheless, this program could be adapted in other clinical settings with a reasonable budget. With increased emphasis on the behavioral modification throughout this program, we observed changes in participant perception and attitude toward eating behavior and physical activity.

One-year follow-up

A significant change (P<0.01) in body weight was observed after 1 year compared to baseline (~4%). This result comparable to the meta-analysis of 22 translational studies where the intervention arms showed a weight loss of 2.3 in 12 months.Citation29 Emiratis women participating in LIFE-8 could maintain their weight loss for 1 year, probably in part because they were more familiar, competent, and comfortable with the know-how of weight management and were to practice it in grocery purchase, food preparation, portioning, increasing physical activity, and recognition cues for overeating. We believe that these changes improve the possibility of lasting weight loss. While the program delivered a modest weight loss, it could not continue further weight loss after the cessation of the intensive program.

A subgroup analysis of glycemic control in T2D participants (n=9) showed a significant improvement (P<0.05) in fasting plasma glucose (8.2±2.0 mmol/L vs 6.6±0.8 mmol/L) and HbA1c (7.1%±1.0% vs 6.3%±0.7%) even after 1 of the program. Haimoto et al have reported a significant improvement in HbA1c after 2 years in patients with T2D on loose restriction of carbohydrate intake compared to conventional diet. However, whether the improvement in glycemic control is a result of weight loss or changes in total energy and nutrient intake is still being investigated.Citation30 The National Health Interview Survey studied 1,401 overweight diabetic patients and reported that individuals trying to lose weight had 23% lower mortality rate than others, suggesting that eating less may have a beneficial effect in the long term even if weight loss is not achieved.Citation31

The strength of this study is that this is one of the first evaluations of a lifestyle intervention program for obese and diabetic participants in this region. The program was developed based on available evidence and comprehensive clinical experience with the local Emirati community. However, the limitations to this study are the small sample size and its nonrandomized, pragmatic service assessment. The program has not been systematically compared with a control intervention program, and the sample included only women. Further evidence is required from a randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the short-term and long-term clinical advantages and cost-effectiveness of the LIFE-8 program in this region. Since this is an ongoing program, further studies with a larger sample size could increase the generalizability of the program.

Conclusion

With a high prevalence of obesity and diabetes in the UAE, an effective, affordable, acceptable, and adaptable lifestyle intervention program could add to the efforts essential for the prevention and management of diabetes. The LIFE-8 program was successful in not only delivering a modest weight loss but also inducing improvement in glycemic control in diabetic participants. In addition, participants also maintained their body weight after a 12-month follow-up. However, there is a need for further analysis on a larger number of participants and execute the program in other health care facilities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and clinical staff for their support and cooperation. This program was supported by grants from the Rashid Center for Diabetes and Research and the Global Health Partner (Gothenburg, Sweden).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Malik M Bakir A Saab BA King H Glucose intolerance and associated factors in the multi-ethnic population of the United Arab Emirates: results of a national survey Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005 69 188 195 16005369

- Hajat C Harrison O Shather Z A profile and approach to chronic disease in Abu Dhabi Global Health 2012 8 18 22738714

- Kelley DE Managing obesity as first-line therapy for diabetes mellitus Nutr Clin Care 1998 1 38 43

- Virtanen KA Iozzo P Hällsten K Increased fat mass compensates for insulin resistance in abdominal obesity and type 2 diabetes: a positron-emitting tomography study Diabetes 2005 54 9 2720 2726 16123362

- Maggio CA Pi-Sunyer FX The prevention and treatment of obesity. Application to type 2 diabetes Diabetes Care 1997 20 11 1744 1766 9353619

- Van Gaal LF Mertens IL Ballaux D What is the relationship between risk factor reduction and degree of weight loss? Eur Heart J Suppl 2005 7 suppl L L21 L26

- Knowler WC Barrett-Connor E Fowler SE Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin N Engl J Med 2002 346 6 393 403 11832527

- Evidence Analysis Library [webpage on the Internet] Adult Weight Management Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline, Evidence Analysis Library, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics ADA Evidence Analysis Library Available from: http://andevidencelibrary.com/topic.cfm?format_tables=0&cat=3014&auth=1 Accessed March 21, 2013

- Unick JL Beavers D Jakicic JM Look AHEAD Research Group Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions for individuals with severe obesity and type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD trial Diabetes Care 2011 34 10 2152 2157 21836103

- Paulweber B Valensi P Lindström J A European evidence-based guideline for the prevention of type 2 diabetes Horm Metab Res 2010 42 Suppl 1 S3 S36 20391306

- Neiberg RH Wing RR Bray GA Look AHEAD Research Group Patterns of weight change associated with long-term weight change and cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Look AHEAD Study Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012 20 10 2048 2056 22327053

- Ali HI Bernsen RM Baynouna LM Barriers to weight management among Emirati women: a qualitative investigation of health professionals’ perspectives Int Q Community Health Educ 2008–2009 29 2 143 159 19546089

- Kahan D Prevalence and correlates of adult overweight in the Muslim world: analysis of 46 countries Clin Obes 2015 5 2 87 98 25755091

- LSU Hospitals [webpage on the Internet] Assessing Patient Readiness for Change and Making Treatment Options Available from: http://www.lsuhospitals.org/cmo/hcet/docs/obesityclinical/Patient_Readiness.pdf Accessed January 27, 2016

- Evert AB Boucher JL Cypress M Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes Diabetes Care 2014 37 Suppl 1 S120 S143 24357208

- Donnelly JE Blair SN Jakicic JM American College of Sports Medicine American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009 41 2 459 471 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333 19127177 Erratum Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009 41 7 1532

- Bray GA [webpage on the Internet] Obesity in adults: behavioral therapy Available from http://www.uptodate.com/contents/obesity-in-adults-behavioral-therapy?source=search_result&search=obesity+in+adults+behavioral+therapy&selectedTitle=1~150 Accessed January 27, 2016

- Cullen KW Baranowski T Smith SP Using goal setting as a strategy for dietary behavior change J Am Diet Assoc 2001 101 5 562 566 11374350

- Rao G Burke LE Spring BJ American Heart Association Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism Council on Clinical Cardiology Council on Cardiovascular Nursing Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease Stroke Council New and emerging weight management strategies for busy ambulatory settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association endorsed by the Society of Behavioral Medicine Circulation 2011 124 10 1182 1203 21824925

- Simkin-Silverman LR Gleason KA King WC Predictors of weight control advice in primary care practices: patient health and psychosocial characteristics Prev Med 2005 40 1 71 82 15530583

- Ward SH Gray AM Paranjape A African Americans’ perceptions of physician attempts to address obesity in the primary care setting J Gen Intern Med 2009 24 5 579 584 19277791

- Ali MK Echouffo-Tcheugui J Williamson DF How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 31 1 67 75 22232096

- Baillot A Romain AJ Boisvert-Vigneault K Effects of lifestyle interventions that include a physical activity component in class II and III obese individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis PLoS One 2015 10 4 e0119017 25830342

- Aucott LS Influences of weight loss on long-term diabetes outcomes Proc Nutr Soc 2008 67 1 54 59 18234132

- Kramer MK Kriska AM Venditti EM Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program: a comprehensive model for prevention training and program delivery Am J Prev Med 2009 37 6 505 511 19944916

- Graffagnino CL Falko JM La Londe M Effect of a community-based weight management program on weight loss and cardiovascular disease risk factors Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006 14 2 280 288 16571854

- Pekarik G The effects of program duration on continuance in a behavioral weight loss program Addict Behav 1987 12 4 381 384 3687523

- Kalter-Leibovici O Younis-Zeidan N Atamna A Lifestyle intervention in obese Arab women: a randomized controlled trial Arch Intern Med 2010 170 11 970 976 20548010

- Dunkley AJ Bodicoat DH Greaves CJ Diabetes prevention in the real world: effectiveness of pragmatic lifestyle interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes and of the impact of adherence to guideline recommendations: a systematic review and meta-analysis Diabetes Care 2014 37 4 922 933 10.2337/dc13-2195 24652723 Review Erratum Diabetes Care 2014 37 6 1775 1776

- Haimoto H Iwata M Wakai K Umegaki H Long-term effects of a diet loosely restricting carbohydrates on HbA1c levels, BMI and tapering of sulfonylureas in type 2 diabetes: a 2-year follow-up study Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008 79 2 350 356 17980451

- Gregg EW Gerzoff RB Thompson TJ Williamson DF Trying to lose weight, losing weight, and 9-year mortality in overweight U.S. adults with diabetes Diabetes Care 2004 27 3 657 662 14988281