Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is associated with depressive symptoms, and comorbid depression in those with T2DM has been associated with adverse clinical profiles. Recognizing and addressing psychological symptoms remain significant clinical challenges in T2DM. Possible mediators of the reciprocal relationship between T2DM and depression may include physical activity levels, effectiveness of self-management, distress associated with a new T2DM diagnosis, and frailty associated with advanced diabetes duration. The latter considerations contribute to a “J-shaped” trajectory from the time of diagnosis. There remain significant challenges to screening for clinical risks associated with psychological symptoms in T2DM; poorer outcomes may be associated with major depressive episodes, isolated (eg, anhedonic), or subsyndromal depressive symptoms, depressive-like symptoms more specific to T2DM (eg, diabetes-related distress), apathy or fatigue. In this review, we discuss current perspectives on depression in the context of T2DM with implications for screening and management of these highly comorbid conditions.

Introduction

The likelihood of depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is approximately double that found in the general population.Citation1–Citation3 The cardinal symptoms of a major depressive episode according to Diagnostic And Statistical Manual Of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition criteria are sadness and/or anhedonia with additional symptoms of decreased energy, changes in thinking, appetite changes, disrupted sleep, or suicidality.Citation4,Citation5 These symptoms may occur together or in isolation in people with T2DM. Depression or depressive symptoms have been associated with adverse clinical profiles, including poorer glycemic control, eating habits,Citation6,Citation7 and exercise adherenceCitation8 in those with T2DM. Despite their importance, recognizing and addressing psychological symptoms in T2DM remain significant clinical challenges.

There has been considerable debate over the past decade about the most important symptom clusters, psychological constructs, and screening tools. Clinical outcomes have been associated with specific symptoms of major depression (eg, anhedonia),Citation9,Citation10 isolated or subsyndromal depressive symptoms that are not part of a depressive episode,Citation7 fatigue, or depressive-like symptoms more specific to the burden of T2DM (ie, diabetes-related distress).Citation2,Citation9,Citation11 Recent studies suggest that duration of diabetes may be an important factor in the temporal trend of depressive symptoms at the population level, likely due to the development and severity of diabetes-related distress and frailty.Citation12–Citation15 In this review, we discuss current perspectives on diabetes and depression with implications for screening and management of these highly comorbid conditions. Our primary aims were to summarize temporal trends in depressive symptoms, overlapping psychosocial constructs and the instruments used to assess them, possible implications for pharmacotherapy, and the impact of comorbid diabetes and depression on longer-term outcomes.

Depression and diabetes: a reciprocal causal relationship?

Questions remain concerning causality in the reciprocal relationships identified between diabetes and depression.Citation15,Citation16 Epidemiological studies indicate that depression is a risk factor for future diabetesCitation17,Citation18 and that diabetes is a risk factor for future depression.Citation19 It has been proposed that depressive symptoms act as mediators of subsequent metabolic disruptions due to their effects on activity levels and other health behaviors.Citation20,Citation21

Some evidence that T2DM can cause depression has been gleaned from Mendelian randomization studies,Citation22–Citation24 in which single-nucleotide polymorphisms known to predispose T2DM were also predictors of anhedonic, interpersonal, somatic, and other depressive symptoms – suggesting that diabetes can cause depressive symptoms.Citation25 It has been suggested that distress associated with a new T2DM diagnosis might precipitate or exacerbate depressive symptomsCitation19 as in other newly diagnosed chronic diseases.Citation16,Citation26 That view would be consistent with elevated depressive symptoms in patients diagnosed clinically with diabetes compared to those with undiagnosed diabetes.Citation27 Both a diagnosis of diabetesCitation19 and treatment for diabetesCitation16,Citation28,Citation29 have been associated with an increased likelihood of depression.

Depression, distress, and other discontent in T2DM

About 18%–25% of people with T2DM will meet DSM criteria for a major depressive episode using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Axis-I Disorders (SCID), a prevalence at least double that is found in the general population.Citation30–Citation32 Most clinicians would agree that when identified, treatment should be offered for major depressive disorder (MDD); however, depression is a heterogeneous condition,Citation33 and not all symptoms of MDD are related to diabetes outcomes in the same way. Of particular interest, anhedonia can occur as a cardinal symptom of a major depressive episode, as an isolated symptom, as a personality trait, or as a neuroendocrine symptom of T2DM.Citation9 According to the DSM-5, anhedonia is characterized by the “lack of enjoyment from, engagement in, and energy for life experiences”.Citation34 Anhedonia has been associated with suboptimal glucose control, increasing the odds of having HbA1c levels ≥7 by 30%.Citation10 Moreover, in a prospective study, anhedonia specifically (not dysphoria) increased the risk of mortality, and this was mediated by physical activity.Citation35 Given that this cardinal depressive symptom can occur in patients with T2DM, in constellation with other depressive symptoms that might meet criteria for a diagnosis of MDD, it might be useful to consider that some cases might be more reflective of a diabetes-related depressive syndrome rather than MDD per se. Basic neuroscience studies suggest different neuroanatomical and neurochemical underpinnings of different facets of anhedonia (eg, consummatory, decisional, motivational, and anticipatory),Citation36 which are not generally discerned in structured clinical interviews. Motivational and/or decisional aspects of anhedonia may link dopaminergic dysfunction with diabetes-related distress, major depression, and fatigue, which might interfere with the management of diabetes.Citation9

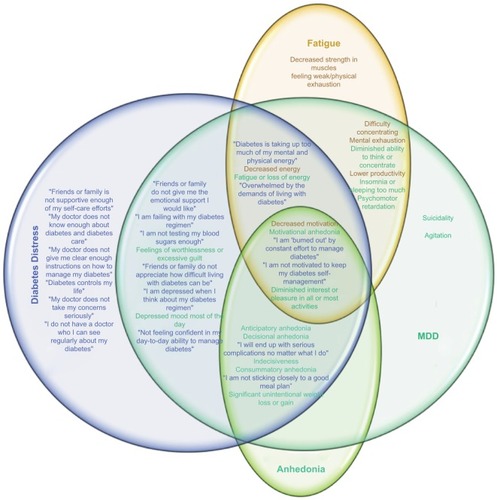

Depression heightens the psychological impact of a diagnosis of diabetes, resulting in increased diabetes-related distress.Citation37 Diabetes-related distress is a construct more specific to the psychological burden of a diagnosis of diabetes and its management,Citation2,Citation38 and many of its tenets overlap with the symptoms of major depression.Citation39,Citation40 As shown in , the constructs of depression and distress capture elements of fatigue,Citation4,Citation41 anhedonia, and dysphoria.Citation2,Citation42 These constellations of symptoms may result in functional impairment, problems in self-management, poorer glycemic control, increased risk of diabetes complications, and poorer quality of life.Citation2

Figure 1 Venn diagram exploring intersections between symptoms of MDD (teal), diabetes-related distress (blue), fatigue (orange), and anhedonia (green).

Abbreviations: DDS, Diabetes Distress Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder.

One specific domain of diabetes-related distress relates to the burden of management. Patients prescribed a multi-factorial treatment plan show more distress in their first year following diagnosis, but patients undergoing less intensive treatments may not develop distress for several years after diagnosis.Citation43 As the burden of management increases, so do symptoms of distress; in a Chinese population-based study, burden of insulin use, but not depression, correlated with the duration of diabetes.Citation44 Conceivably, the need to use insulin can lead to negative health perceptions, resulting in increased distress. Accordingly, in another study, diabetes-related distress, but not depression, correlated with HbA1c.Citation45 This might be expected since unlike depression, diabetes-related distress is defined by specific, contextual stressors relating to diabetes, also indexing the impact of depression.Citation38

Fatigue is associated with poorer day-to-day functioning attributable to symptoms of tiredness, lack of energy, or exhaustion.Citation41 It is differentiated from an acute state of tiredness (which can occur normally) as a chronic state whereby the body is nonresponsive to rest. Fatigue is a barrier to participation in physical activities and to engagement in self-care activities in T2DM.Citation41 Both DSM depression criteria and many screening tools for depressive symptoms, such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), include symptoms of fatigue. Notably, in a recent validation of the CES-D in T2DM, the fatigue item was found, in differential item functioning testing, to be non-invariant with respect to glycemic control, suggesting that fatigue in T2DM was more closely related to symptoms of T2DM than symptoms of depression per se.Citation46 This might inflate depressive symptom estimates, particularly “somatic symptoms” in T2DM, and affect the accuracy of screening. Similarly, the probability to endorse the item “feeling that diabetes is taking up too much of my mental and physical energy every day” on the Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS)Citation47 is likely to be related to fatigue and also to an inability to apply self-care strategies. In patients with T2DM with an HbA1c >7%, fatigue is associated with pain and inflammation.Citation47 Anhedonia and fatigue have been related to inflammation,Citation48 and they may be convergent constructs in T2DM. One study, aiming to understand complications associated with newly diagnosed patients with T2DM, found that fatigue was reported by 61% of patients. In that study, fatigue was significantly associated with fasting plasma glucose but not with HbA1c.Citation49 Another construct closely related to anhedonia and fatigue is apathy, which can be screened using the Apathy Evaluation Scale or diagnosed based on a clinical assessment.Citation50 Symptoms of apathy are more common in T2DM, and they are related to depression, poorer glycemic control, and cognitive decline.Citation51

Duration of diabetes and depression

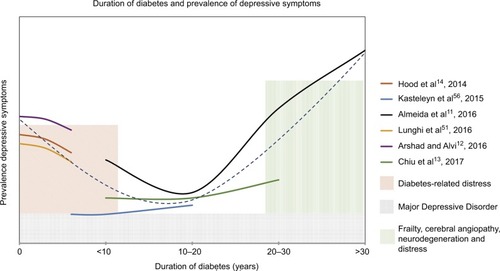

For many of the reasons mentioned earlier, duration of diabetes influences depressive symptoms, contributing to a “J-shaped” curve over time in T2DM as shown in . In general, depressive symptoms elevate immediately following diagnosis and then decrease over several years, increasing again with longer duration. In one study using a cutoff of 7 on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), durations of diabetes <10 years or >30 years were associated with increased odds of depression, whereas durations such as 10–30 years were not.Citation12 The increase in depression with longer durations of diabetes was shown to be mediated by increased frailty scores.Citation12

Figure 2 Temporal trend in depressive symptoms with duration of diabetes.

Abbreviation: MDD, major depressive disorder.

In another T2DM population, about 40% of the study population was depressed according to the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 with shorter duration of diabetes predicting increased occurrence of depression.Citation13 However, in a study examining the relationship between various chronic conditions and depressive symptoms, no increase in depressive symptoms was observed after initial diagnosis of diabetes;Citation14 instead, specific to diabetes, there was a gradual increase in these symptoms over time, consistent with the latter portion of the J-shaped model. In another study, a peak in depressive symptoms, as measured by the CES-D, was observed at baseline, with a gradual decrease over the next 6 years, also consistent with the proposed J-shaped model of depressive symptoms in T2DM.Citation15 Although not specifically tested, these, the initial increase in depressive symptoms in shorter durations, might be related to distress associated with a diagnosis and newly imposed management regimes (eg, additional medications, checking blood sugar, dieting, and exercise).Citation49 An increased incidence of depression has been observed within the first year of initiation of an oral antidiabetic medication.Citation50 After an adjustment to management and/or remaining generally asymptomatic with respect to diabetes complications, depressive symptoms may then subside. Some studies have suggested that older adults with T2DM have been more successful in meeting T2DM outcome standards when compared to younger adults, and this was not due to either increased disease knowledge or shorter disease duration.Citation53–Citation55 In these studies, the duration of diabetes of the older patients falls within the dip in our proposed J-shaped curve, supporting the suggestion that this relatively longer duration of T2DM may be associated with adjustment to diabetes-related lifestyle changes. With further increased duration of diabetes, cerebral microvascular complications may contribute to symptoms such as anhedonia and apathy.Citation56 Both macrovascular and microvascular complications have been associated with an increase in incident depressive symptoms.Citation57 In addition, more taxing management regimes may increase distress;Citation58 for instance, the need for insulin injection may lead to a negative outlook on overall health.Citation59–Citation61 Moreover, at longer durations of diabetes, other chronic comorbidities typically accumulate, resulting in increased frailty, which is characterized by decreased physical capability, increased exhaustion, and poorer weight loss outcomesCitation62,Citation63 in T2DM. Because depression is a heterogeneous condition, more data on temporal trends in individual depressive symptom domains will be important to discern in future studies.

Depression screening and diagnosis

Depression is diagnosed in a structured clinical interview, such as the SCID.Citation64,Citation65 Other interviews include the following: the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). However, these interviews vary in length and they can be time-consuming and increasing patient burden, and depression can be screened accurately using as few as two questions (eg, the PHQ-2).

The high rate of comorbid depression in T2DM, and the heterogeneity of its symptoms, necessitates some additional considerations in this population. The accuracy of the tests can vary between populations, necessitating comparison against the gold standard interviews to determine optimal cutoff scores to detect depression. In addition, psychometric evaluation is required to determine the suitability of the individual items and overall construct validity specifically in T2DM.Citation66 The properties of various screening instruments and their validities in T2DM remain an ongoing area of study.Citation67 Differential item functioning is one analysis that can be used to determine whether the questions on each are non-invariant with respect to T2DM and/or T2DM characteristics to ensure that they accurately measure depressive symptoms rather than symptoms of T2DM.Citation68,Citation69 Self-report screening questionnaires used in T2DM include the following: the CES-D,Citation46 Beck Depression Inventory (BDI),Citation70 World Health Organization (WHO) Well-Being Index,Citation71 PHQ,Citation72 and Edinburg Depression Scale (EDS), among others.Citation67 The self-report scales used most commonly in T2DM, and studies assessing their validity, have been reviewed recently.Citation67

One of the most commonly used and best supported questionnaires to screen for depression is the CES-D,Citation67 which contains 20 items and is used to assess depressive symptoms that occur in the previous week with individual item scores ranging from 0 to 3. Scores can range from 0 to 60 with higher scores indicating the presence of more depressive symptoms, and a cutoff of 16 or greater is suggested to indicate significant depressive symptoms in the general population. Although this cutoff was appropriate to predict non-completion of exercise in patients with coronary artery disease,Citation73 a cutoff of 10 was found to predict non-completion of exercise in T2DM.Citation7 An abridged (14-item) version of the CES-D was proposed based on invariance testing,Citation74 and the 14-item version was validated for use in patients with T2DM,Citation46 although optimal cutoffs to detect a major depressive episode, and risks of non-adherent behaviors, remain to be determined. The subdomains capture anhedonia, sadness, and somatic symptoms, the latter two almost perfectly correlated, and all of the items are best viewed as a single measure of depression overall.Citation46

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was originally designed to capture the severity of depression using 21 items indicating psychological and somatic symptoms in the previous week with four ordered response categories. The cutoff for the general population using the BDI-I is a summed score of 13 or greater, but a cutoff of 16 or greater was suggested to be more accurate in diabetes.Citation70,Citation75 Using this cutoff, there is an overall prevalence of 32.8% in diabetes.Citation76 The BDI has been revised (BDI-II), although the psychometric properties of the scale and possible subdomains remain to be explored in-depth in T2DM.Citation77–Citation79

The WHO Well-Being Index is unique in that it contains five positively worded items that assess the absence of positive mood during the previous 2 weeks. It utilizes a 6-point frequency scale resulting in a well-being score that can range from 0 to 25.Citation80,Citation81 A higher well-being score is considered to be an overall indicator of positive mental health, but items do not quantify any specific subdomains of depression.Citation82 The cutoff for the general population that indicates “poor” well-being is 13 or lower, but the ideal cutoff for patients with T2DM was found to be 10 or lower.Citation80 Approximately 79.5% of respondents with T2DM were correctly described to have an absence of depressive symptoms based on this cutoff score.Citation80,Citation81

Another effective screening tool is Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9, which contains nine items that measure the frequency of depressive symptoms with a 4-point Likert scale. In this review, the scale items capture anhedonia, depressed mood, insomnia, and energy level. A total score of 10 or greater is indicative of depression in the general population, but for patients with T2DM, a cutoff of 12 or greater was found to be more effective.Citation72 It has been suggested that just two questions (the PHQ-2), which probe the two cardinal symptoms of MDD, can also detect MDD with high accuracy in other populations.Citation83

The EDS is a unidimensional questionnaire consisting of 10 items with a 4-point rating scale. The presence of major depression is determined by a score of 12 or 13, whereas scores ranging from 9 to 11 indicate the presence of mild depression. An advantage of using this as a screening tool for depression is the absence of bias by somatic symptoms caused by diabetes itself. Because this test was originally developed to measure postnatal depression, bias by gender-related symptoms may be a concern when summing the scores.Citation81,Citation84 Using the EDS, 9.8% of men with diabetes showed symptoms of mild depression and 8.1% showed severe depressive symptoms, while 16.5% of females showed symptoms of mild depression and 16.2% showed symptoms of severe depression.Citation84 While some have reported that the EDS is multidimensional (quantifying anhedonia, anxiety, and depression),Citation85,Citation86 confirmatory factor analysis has shown that EDS is unidimensional and measures a general depression factor.Citation84

Interventions for comorbid depression and diabetes

Studies suggest that the treatment of comorbid depression and T2DM is more effective when embedded in an integrated approach, in which both conditions are addressed together.Citation87 Pharmacological treatment with antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to be effectiveCitation88 and to prevent the recurrence of depression in patients with diabetes.Citation89 Bupropion, a norepinephrine and dopamine (DA) reuptake inhibitor, would seem to be at least equally effective as SSRIs in T2DM;Citation90 however, it has not been compared head to head with an SSRI in a randomized trial. Treatment with SSRIs or bupropion can help patients achieve better glycemic control.Citation90 No antidepressant therapy has been specifically indicated based on a comorbid diagnosis of T2DM nor have been any particular antidiabetic regimens that might have varying effects on mood indicated for comorbid depression in the setting of T2DM. For instance, in animal models, the glucagon-like peptide 1 agents appear to have antidepressant properties,Citation91 warranting further studies in human beings.

DA plays an important role in both depression and T2DM. There is evidence that a decrease in DA signaling in the striatum occurs in T2DM, and in rodent models of obesity, which could result in decreased psychomotor activity, motivation, and dysfunction of reward systems.Citation92 Apart from its antidepressant properties, DA enhances glycemic control and insulin sensitivity.Citation93 DA agonists (ie, bromocriptine) can decrease food intake and increase locomotor activity.Citation94 Another dopaminergic agent, methylphenidate, has been shown to be effective against symptoms of apathy.Citation95,Citation96 Therefore, agents that increase DA may be more helpful in the management of depression in the context of T2DM compared to other pharmacological agents, as they may improve apathy, depressive symptoms, and glycemic control, and they may also assist with cognition and motivation to improve lifestyle factors.

Anti-inflammatory agents are under investigation for depression in the setting of inflammatory comorbidity and treatment-resistant depression. A bidirectional relationship between inflammation and T2DM has been observed, and depression is associated with inflammation in T2DM,Citation97,Citation98 suggesting that anti-cytokineCitation99,Citation100 or other anti-inflamamtoryCitation101,Citation102 approaches may be useful as additional or adjunctive therapies.

Non-pharmacological interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),Citation103 interpersonal therapy,Citation104 and exercise intervention programs,Citation8,Citation105,Citation106 can be prescribed. CBT utilizes behavioral strategies, problem-solving procedures, and cognitive techniques in treatment.Citation103 Alongside diabetes education, CBT was found to be effective, with 58.3% of patients in the CBT group achieving remission vs 25.9% who received diabetes education alone.Citation103 In that study, glycemic control was improved; however, in a more recent study, CBT showed no benefit on glycemic control and less effectiveness than sertraline on glycemic control.Citation107

Interpersonal therapy is a personalized approach that recognizes cultural, social, and psychological contexts that may affect adherence to medication or treatment.Citation104 Discussion of treatment options and education can be integrated into this framework to optimize medication use.Citation108 In one study, the intervention of an integrated care manager had significant effects on clinical outcomes for both depression and diabetes, which was due to increased adherence to medications and treatment recommendation.Citation104

Exercise improves depressive symptoms,Citation106,Citation109 glucose disposal, insulin sensitivity, and glycemic control.Citation105,Citation110 This may be partially attributed to recruitment of DA and striatal circuits for reward and stress resistance.Citation111 However, a systematic review highlighted heterogeneity in the effects of exercise on psychological outcomes in T2DM.Citation112 Although many benefits of exercise appear to occur regardless of exercise modality,Citation105,Citation110 that work suggests the need to identify optimal regimes and/or predictors of response.

Multiple approaches were utilized in a three-phase collaborative primary team model designed for patients with comorbid diabetes and depression. The three phases included the following: improvement in depressive symptoms; improvement in blood glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol; and improvement in self-care behaviors. This collaborative care model was found to have benefit in both diabetes and depression outcomes, emphasizing the benefit of a holistic approach.Citation113

Clinical sequelae of depression in diabetes

As discussed, depression in T2DM has been associated with poorer glycemic control in some,Citation6,Citation30 but not allCitation13,Citation114 studies. Moreover, treatment for depression improves glycemic control in some,Citation90,Citation93,Citation103,Citation110 but not allCitation115,Citation116 studies. One study investigating the effect of bupropion on depressed patients with T2DM found mood-related reductions in HbA1c, independent of changes in diabetes self-care practices.Citation117 Some discrepancies between studies may have to do with the symptoms assessed or heterogeneity in depression diagnoses. For instance, anhedonic symptoms may correlate more closely with glycemic control than other depressive symptomsCitation9,Citation10,Citation35,Citation118,Citation119 and with prospective mortality risk due to their effects on physical activity.Citation35 Depression in people with diabetes increases the risks of stroke, cardiovascular mortality,Citation120 and all-cause mortality.Citation121–Citation123

Both T2DM and depression are associated with a decline in cognitive function due to multiple effects on the brain. For instance, diabetes is associated with an increased rate of cortical atrophy,Citation124 microvascular brain disease, and deficits in cerebral blood flow.Citation125,Citation126 A population-based study found that having the two conditions together was associated with a more-than-additive effect in increasing the risk of dementia.Citation127 Diabetes and depression co-occurring in a post-stroke population also had a cumulative impact on executive function and on the risk of severe vascular cognitive impairment.Citation128 It is conceivable that diabetes and depression co-contribute a neural environment that places the brain at risk for dementia due to inflammation,Citation98 neuroendocrine changes associated with chronic stress,Citation129 microangiopathic changes, and an increased propensity for subcortical infarcts.Citation130 Notably, educational attainment has been found to decrease the risk of depression in people with T2DM,Citation13,Citation131 which might bolster cognitive reserve against brain loss. Sophisticated mediation modeling has been used to examine relationships between diabetes, depression, and cognitive outcomes over time, demonstrating a direct effect of T2DM on cognition, and an indirect effect that is mediated by depression.Citation132 Studies of this type might also be useful to disentangle the temporal relationships between diabetes and depression themselves.

Conclusion

Although there is debate surrounding the bidirectional relationship between diabetes and depression, it is clear that the two conditions occurring together can make both conditions more difficult to manage, and contribute additively to adverse long-term sequelae such as mortality, stroke, and dementia. There are challenges in identifying the most harmful symptoms of depression in the context of diabetes with subsyndromal symptoms and depression-like symptoms posing considerable barriers to effective management. Due to overlap in the multiple relevant psychological symptoms, it will be important to examine further the properties of different psychometrics, including those designed to capture more specific subdomains, in T2DM, with careful attention to how these constructs may uniquely predict different aspects of the management of diabetes and clinical outcomes over the different epochs of duration of diabetes. It may be particularly important to recognize and distinguish between diabetes-related distress, frailty, fatigue, apathy, anhedonia, and clinical depression in studies assessing the effectiveness of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment modalities for T2DM. Particular attention should be paid to manage T2DM and psychological conditions together.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Mommersteeg PMC Herr R Pouwer F Holt RIG Loerbroks A The association between diabetes and an episode of depressive symptoms in the 2002 World Health Survey: an analysis of 231 797 individuals from 47 countries Diabet Med 2013 30 6 e208 e214 23614792

- Fisher L Skaff MM Mullan JT Clinical depression versus distress among patients with type 2 diabetes: not just a question of semantics Diabetes Care 2007 30 3 542 548 17327318

- Nouwen A Winkley K Twisk J Type 2 diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for the onset of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis Diabetologia 2010 53 12 2480 2486 20711716

- Lopez Molina MA Jansen K Drews C Pinheiro R Silva R Souza L Major depressive disorder symptoms in male and female young adults Psychol Health Med 2014 19 2 136 145 23651450

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th ed Arlington, VA American Psychiatric Publishing 2013

- Lin EHB Katon W Von Korff M Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care Diabetes Care 2004 27 9 2154 2160 15333477

- Gonzalez JS Peyrot M McCarl LA Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis Diabetes Care 2008 31 12 2398 2403 19033420

- Swardfager W Yang P Herrmann N Depressive symptoms predict non-completion of a structured exercise intervention for people with type 2 diabetes Diabet Med 2016 33 4 529 536 26220364

- Carter J Swardfager W Mood and metabolism: anhedonia as a clinical target in type 2 diabetes Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016 69 123 132 27088371

- Nefs G Pouwer F Denollet J Kramer H Wijnands-van Gent CJ Pop VJ Suboptimal glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a key role for anhedonia? J Psychiatr Res 2012 46 4 549 554 22284972

- Naicker K Øverland S Johnson JA Symptoms of anxiety and depression in type 2 diabetes: associations with clinical diabetes measures and self-management outcomes in the Norwegian HUNT study Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017 84 116 123 28704763

- Almeida OP McCaul K Hankey GJ Duration of diabetes and its association with depression in later life: the Health in Men Study (HIMS) Maturitas 2016 86 3 9 26921921

- Arshad AR Alvi KY Frequency of depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus and an analysis of predictive factors J Pak Med Assoc 2016 66 4 425 429 27122269

- Chiu CJ Hsu YC Tseng SP Psychological prognosis after newly diagnosed chronic conditions: socio-demographic and clinical correlates Int Psychogeriatr 2017 29 2 281 292 27804908

- Hood KK Beavers DP Yi-Frazier J Psychosocial burden and glycemic control during the first 6 years of diabetes: results from the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study J Adolesc Health 2014 55 4 498 504 24815959

- Tabák AG Akbaraly TN Batty GD Kivimäki M Depression and type 2 diabetes: a causal association? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014 2 3 236 2452 24622754

- Rotella F Mannucci E Depression as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies J Clin Psychiatry 2013 74 1 31 37 23419223

- Eaton WW Armenian H Gallo J Pratt L Ford DE Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes: a prospective population-based study Diabetes Care 1996 19 10 1097 1102 8886555

- Rotella F Mannucci E Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for depression. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2013 99 2 98 104 23265924

- Moulton CD Pickup JC Ismail K The link between depression and diabetes: the search for shared mechanisms Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015 3 6 461 471 25995124

- Renn BN Feliciano L Segal DL The bidirectional relationship of depression and diabetes: a systematic review Clin Psychol Rev 2011 31 8 1239 1246 21963669

- Lawlor DA Harbord RM Tybjaerg-Hansen A Using genetic loci to understand the relationship between adiposity and psychological distress: a Mendelian Randomization study in the Copenhagen General Population Study of 53 221 adults J Intern Med 2011 269 5 525 537 21210875

- Hung CF Rivera M Craddock N Relationship between obesity and the risk of clinically significant depression: Mendelian randomisation study Br J Psychiatry 2014 205 1 24 28 24809401

- Hartwig FP Bowden J Loret De Mola C Tovo-Rodrigues L Davey Smith G Horta BL Body mass index and psychiatric disorders: a Mendelian randomization study Sci Rep 2016 6 32730 27601421

- Brewster P Gross A Gibbons LE Mukherjee S Crane PK Glymour MM The structure of depression in relation to type II diabetes: a Mendelian randomization analysis Gerontologist 2015 55 525 525

- Almeida OP Vascular depression: myth or reality? Int Psychogeriatrics 2008 20 4 645 652

- Nouwen A Nefs G Caramlau I Prevalence of depression in individuals with impaired glucose metabolism or undiagnosed diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) research consortium Diabetes Care 2011 34 3 752 762 21357362

- Kivimki M Batty GD Jokela M Antidepressant medication use and risk of hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus-a noncausal association? Biol Psychiatry 2011 70 10 978 984 21872216

- Wahlqvist ML Lee MS Chuang SY Increased risk of affective disorders in type 2 diabetes is minimized by sulfonylurea and metformin combination: a population-based cohort study BMC Med 2012 10 150 23194378

- Papelbaum M Moreira RO Coutinho W Depression, glycemic control and type 2 diabetes Diabetol Metab Syndr 2011 3 1 26 21978660

- De Groot M Jacobson AM Samson JA Welch G Glycemic control and major depression in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus J Psychosom Res 1999 46 5 425 435 10404477

- Pibernik-Okanovic M Peros K Szabo S Begic D Metelko Z Depression in Croatian type 2 diabetic patients: prevalence and risk factors. A Croatian survey from the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) Research Consortium Diabet Med 2005 22 7 942 945 15975112

- Goldberg D The heterogeneity of “major depression” World Psychiatry 2011 10 3 226 228 21991283

- American Psychiatric Association DSM-V Washington, DC APA 2013

- Nefs G Pop VJM Denollet J Pouwer F Depressive symptoms and all-cause mortality in people with type 2 diabetes: a focus on potential mechanisms Br J Psychiatry 2016 209 2 142 149 26846613

- Treadway MT Zald DH Reconsidering anhedonia in depression: lessons from translational neuroscience Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011 35 3 537 555 20603146

- Fisher L Skaff MM Mullan JT Arean P Glasgow R Masharani U A longitudinal study of affective and anxiety disorders, depressive affect and diabetes distress in adults with type 2 diabetes Diabet Med 2008 25 9 1096 1101 19183314

- Fisher L Gonzalez JS Polonsky WH The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision Diabet Med 2014 31 7 764 772 24606397

- Katon WJ Russo JE Heckbert SR The relationship between changes in depression symptoms and changes in health risk behaviors in patients with diabetes Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010 25 5 466 475 19711303

- Fisher L Hessler DM Polonsky WH Mullan J When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful? Establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress Scale Diabetes Care 2012 35 2 259 264 22228744

- Fritschi C Quinn L Fatigue in patients with diabetes: a review J Psychosom Res 2010 69 1 33 41 20630261

- Snoek FJ Bremmer MA Hermanns N Constructs of depression and distress in diabetes: time for an appraisal Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015 3 6 450 460 25995123

- Ismail K Moulton CD Winkley K The association of depressive symptoms and diabetes distress with glycaemic control and diabetes complications over 2 years in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study Diabetologia 2017 60 10 2092 2102 28776084

- Sun JC Xu M Lu JL Associations of depression with impaired glucose regulation, newly diagnosed diabetes and previously diagnosed diabetes in Chinese adults Diabet Med 2015 32 7 935 943 25439630

- Fisher L Mullan JT Arean P Glasgow RE Hessler D Masharani U Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses Diabetes Care 2010 33 1 23 28 19837786

- Carter J Cogo-Moreira H Herrmann N Validity of the center for epidemiological studies Depression Scale in type 2 diabetes J Psychosom Res 2016 90 91 97 27772565

- Park H Park C Quinn L Fritschi C Glucose control and fatigue in type 2 diabetes: the mediating roles of diabetes symptoms and distress J Adv Nurs 2015 71 7 1650 1660 25690988

- Swardfager W Rosenblat JD Benlamri M McIntyre RS Mapping inflammation onto mood: inflammatory mediators of anhedonia Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016 64 148 166 26915929

- Drivsholm T de Fine ON Nielsen AB Siersma V Symptoms, signs and complications in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients, and their relationship to glycaemia, blood pressure and weight Diabetologia 2005 48 2 210 214 15650820

- Marin RS Biedrzycki RC Firinciogullari S Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale Psychiatry Res 1991 38 2 143 162 1754629

- Bruce DG Nelson ME Mace JL Davis WA Davis TME Starkstein SE Apathy in older patients with type 2 diabetes Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015 23 6 615 621 25458810

- Lunghi C Moisan J Gregoire JP Guenette L Incidence of depression and associated factors in patients with type 2 diabetes in Quebec, Canada: a population-based cohort study Medicine 2016 95 21 e3514 27227919

- Sajatovic M Gunzler D Einstadter D Clinical characteristics of individuals with serious mental illness and type 2 diabetes Psychiatr Serv 2015 66 2 197 199 25642615

- Sajatovic M Gunzler D Einstadter D A preliminary analysis of individuals with serious mental illness and comorbid diabetes Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2016 30 2 226 229 26992875

- Cebul RD Love TE Jain AK Hebert CJ Electronic health records and quality of diabetes care N Engl J Med 2011 365 825 833 21879900

- Lavretsky H Zheng L Weiner MW The MRI brain correlates of depressed mood, anhedonia, apathy, and anergia in older adults with and without cognitive impairment or dementia Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008 23 10 1040 1050 18412291

- Deschênes SS Burns RJ Pouwer F Schmitz N Diabetes complications and depressive symptoms: prospective results from the montreal diabetes health and well-being study Psychosom Med 2017 79 5 603 612 28060138

- Kasteleyn MJ de Vries L van Puffelen AL Diabetes-related distress over the course of illness: results from the diacourse study Diabet Med 2015 32 12 1617 1624 25763843

- Leigh Gibson E Emotional influences on food choice: sensory, physiological and psychological pathways Physiol Behav 2006 89 1 53 61 16545403

- Leventhal AM Relations between anhedonia and physical activity Am J Health Behav 2012 36 6 860 872 23026043

- Holmes-Truscott E Skinner TC Pouwer F Speight J Explaining psychological insulin resistance in adults with non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: the roles of diabetes distress and current medication concerns. Results from diabetes MILES – Australia Prim Care Diabetes 2016 10 1 75 82 26150327

- Almeida OP Hankey GJ Yeap BB Golledge J Norman PE Flicker L Depression, frailty, and all-cause mortality: a cohort study of men older than 75 years J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015 16 4 296 300 25499429

- Morley JE Diabetes, sarcopenia, and frailty Clin Geriatr Med 2008 24 3 455 469 18672182

- Tanenbaum ML Ritholz MD Binko DH Baek RN Erica Shreck MS Gonzalez JS Probing for depression and finding diabetes: a mixed-methods analysis of depression interviews with adults treated for type 2 diabetes J Affect Disord 2013 150 2 533 539 23453278

- Lobbestael J Leurgans M Arntz A Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID I) and axis II disorders (SCID II) Clin Psychol Psychother 2011 18 1 75 79 20309842

- Thombs BD Rice DB Sample sizes and precision of estimates of sensitivity and specificity from primary studies on the diagnostic accuracy of depression screening tools: a survey of recently published studies Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2016 25 2 145 152 27060912

- van Dijk SEM Adriaanse MC van der Zwaan L Measurement properties of depression questionnaires in patients with diabetes: a systematic review Qual Life Res 2018 27 6 1415 1430 29396653

- Teresi JA Ramirez M Lai J-S Silver S Occurrences and sources of Differential Item Functioning (DIF) in patient-reported outcome measures: description of DIF methods, and review of measures of depression, quality of life and general health Psychol Sci Q 2008 50 4 538 20165561

- Gunzler DD Morris N A tutorial on structural equation modeling for analysis of overlapping symptoms in co-occurring conditions using MPlus Stat Med 2015 34 24 3246 3280 26045102

- Lustman PJ Clouse RE Griffith LS Carney RM Freedland KE Screening for depression in diabetes using the beck depression inventory Psychosom Med 1997 59 1 24 31 9021863

- Bech P Gudex C Staehr Johansen K The who (ten) well-being index: validation in diabetes Psychother Psychosom 1996 65 4 183 190 8843498

- Van Steenbergen-Weijenburg KM De Vroege L Ploeger RR Validation of the PHQ-9 as a screening instrument for depression in diabetes patients in specialized outpatient clinics BMC Health Serv Res 2010 10 235 20704720

- Swardfager W Herrmann N Marzolini S Major depressive disorder predicts completion, adherence, and outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation: a prospective cohort study of 195 patients with coronary artery disease J Clin Psychiatry 2011 72 9 1181 1188 21208573

- Carleton RN Thibodeau MA Teale MJN The center for epidemiologic studies Depression Scale: a review with a theoretical and empirical examination of item content and factor structure PLoS One 2013 8 3 e58067 23469262

- Hermanns N Caputo S Dzida G Khunti K Meneghini LF Snoek F Screening, evaluation and management of depression in people with diabetes in primary care Prim Care Diabetes 2013 7 1 1 10 23280258

- Anderson RJ Freedland KE Clouse RE Lustman PJ The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis Diabetes Care 2001 24 6 1069 1078 11375373

- Wang YP Gorenstein C Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: a comprehensive review Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2013 35 4 416 431 24402217

- Beck AT Steer RA Carbin MG Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation Clin Psychol Rev 1988 8 1 77 100

- Wang Y-P Gorenstein C Assessment of depression in medical patients: a systematic review of the utility of the beck depression inventory-II Clinics 2013 68 9 1274 1287 24141845

- Aujla N Skinner TC Khunti K Davies MJ The prevalence of depressive symptoms in a white European and South Asian population with impaired glucose regulation and screen-detected type 2 diabetes mellitus: a comparison of two screening tools Diabet Med 2010 27 8 896 905 20653747

- Hajos TRS Pouwer F Skovlund SE Psychometric and screening properties of the WHO-5 well-being index in adult outpatients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus Diabet Med 2013 30 2 e63 e69 23072401

- Jahoda M Current Concepts of Positive Mental Health 61 1958 New York Basic Books

- Manea L Gilbody S Hewitt C Identifying depression with the PHQ-2: a diagnostic meta-analysis J Affect Disord 2016 203 382 395 27371907

- De Cock ESA Emons WHM Nefs G Pop VJM Pouwer F Dimensionality and scale properties of the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDS) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the DiaDDzoB study BMC Psychiatry 2011 11 141 21864349

- Brouwers EPM van Baar AL Pop VJM Does the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale measure anxiety? J Psychosom Res 2001 51 5 659 663 11728506

- Tuohy A McVey C Subscales measuring symptoms of non-specific depression, anhedonia, and anxiety in the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale Br J Clin Psychol 2008 47 2 153 169 17761026

- van der Feltz-Cornelis CM Nuyen J Stoop C Effect of interventions for major depressive disorder and significant depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010 32 4 380 395 20633742

- Lustman PJ Clouse RE Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control J Diabetes Complications 2005 19 2 113 122 15745842

- Lustman PJ Clouse RE Nix BD Sertraline for prevention of depression recurrence in diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006 63 5 521 529 16651509

- Markowitz S Gonzalez JS Wilkinson JL Safren SA Treating depression in diabetes: emerging findings Psychosomatics 2011 52 1 1 18 21300190

- Anderberg RH Richard JE Hansson C Nissbrandt H Bergquist F Skibicka KP GLP-1 is both anxiogenic and antidepressant; divergent effects of acute and chronic GLP-1 on emotionality Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016 65 54 66 26724568

- Sharma S Fulton S Diet-induced obesity promotes depressive-like behaviour that is associated with neural adaptations in brain reward circuitry Int J Obes 2013 37 3 382 389

- Scranton R Cincotta A Bromocriptine – unique formulation of a dopamine agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes Expert Opin Pharmacother 2010 11 2 269 279 20030567

- Davis LM Michaelides M Cheskin LJ Bromocriptine administration reduces hyperphagia and adiposity and differentially affects dopamine D2 receptor and transporter binding in leptin-receptor-deficient Zucker rats and rats with diet-induced obesity Neuroendocrinology 2009 89 2 152 162 18984941

- Padala PR Padala KP Lensing SY Methylphenidate for apathy in community-dwelling older veterans with mild Alzheimer’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial Am J Psychiatry 2018 175 2 159 168 28945120

- Rosenberg PB Lanctôt KL Drye LT Safety and efficacy of methylphenidate for apathy in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial J Clin Psychiatry 2013 74 8 810 816 24021498

- Stuart MJ Baune BT Depression and type 2 diabetes: inflammatory mechanisms of a psychoneuroendocrine co-morbidity Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2012 36 1 658 676 22020230

- Laake J-PS Stahl D Amiel SA The association between depressive symptoms and systemic inflammation in people with type 2 diabetes: findings from the South London Diabetes Study Diabetes Care 2014 1 1 7

- Kappelmann N Lewis G Dantzer R Jones P Khandaker G Antidepressant activity of anti-cytokine treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of chronic inflammatory conditions Mol Psychiatry 2018 23 2 335 343 27752078

- Raison CL Rutherford RE Woolwine BJ A randomized controlled trial of the Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha antagonist infliximab in treatment resistant depression: role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers JAMA Psychiatry 2013 70 1 31 41 22945416

- Almeida OP Flicker L Yeap BB Alfonso H McCaul K Hankey GJ Aspirin decreases the risk of depression in older men with high plasma homocysteine Transl Psychiatry 2012 2 e151 22872164

- Mendlewicz J Kriwin P Oswald P Souery D Alboni S Brunello N Shortened onset of action of antidepressants in major depression using acetylsalicylic acid augmentation: a pilot open-label study Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2006 21 4 227 231 16687994

- Lustman PJ Griffith LS Cognitive behavior therapy for depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus Ann Intern Med 1998 129 8 613 621 9786808

- Bogner HR Morales KH de Vries HF Cappola AR Integrated management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression treatment to improve medication adherence: a randomized controlled trial Ann Fam Med 2012 10 1 15 22 22230826

- Madden KM Evidence for the benefit of exercise therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2013 6 233 239 23847428

- Mota-Pereira J Silverio J Carvalho S Ribeiro JC Fonte D Ramos J Moderate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder J Psychiatr Res 2011 45 8 1005 1011 21377690

- Petrak F Herpertz S Albus C Cognitive behavioral therapy versus sertraline in patients with depression and poorly controlled diabetes: the Diabetes and Depression (DAD) Study: a randomized controlled multicenter trial Diabetes Care 2015 38 5 767 775 25690005

- Bauer AM Parker MM Schillinger D Associations between antidepressant adherence and shared decision-making, patient-provider trust, and communication among adults with diabetes: diabetes study of northern California (DISTANCE) J Gen Intern Med 2014 29 8 1139 1147 24706097

- Rethorst CD Wipfli BM Landers DM The antidepressive effects of exercise Sport Med 2009 39 6 491 511

- Snowling NJ Hopkins WG Effects of different modes of exercise training on glucose control and risk factors for complications in type 2 diabetic patients: a meta-analysis Diabetes Care 2006 29 11 2518 2527 17065697

- Herrera JJ Fedynska S Ghasem PR Neurochemical and behavioural indices of exercise reward are independent of exercise controllability Eur J Neurosci 2016 43 9 1190 1202 26833814

- van der Heijden MM van Dooren FE Pop VJ Pouwer F Effects of exercise training on quality of life, symptoms of depression, symptoms of anxiety and emotional well-being in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review Diabetologia 2013 56 6 1210 1225 23525683

- Johnson JA Al Sayah F Wozniak L Controlled trial of a collaborative primary care team model for patients with diabetes and depression: rationale and design for a comprehensive evaluation BMC Health Serv Res 2012 12 258 22897901

- Khamseh ME Baradaran HR Javanbakht A Mirghorbani M Yadollahi Z Malek M Comparison of the CES-D and PHQ-9 depression scales in people with type 2 diabetes in Tehran, Iran BMC Psychiatry 2011 22 11 1619 1623

- Georgiades A Zucker N Friedman KE Changes in depressive symptoms and glycemic control in diabetes mellitus Psychosom Med 2007 69 3 235 241 17420441

- van der Ven NC Hogenelst MH Tromp-Wever AM Short-term effects of cognitive behavioural group training (CBGT) in adult type 1 diabetes patients in prolonged poor glycaemic control. A randomized controlled trial Diabet Med 2005 22 11 1619 1623 16241932

- Lustman PJ Williams MM Sayuk GS Nix BD Clouse RE Factors influencing glycemic control in type 2 diabetes during acute- and maintenance-phase treatment of major depressive disorder with bupropion Diabetes Care 2007 30 3 459 466 17327305

- Moskowitz JT Epel ES Acree M Positive affect uniquely predicts lower risk of mortality in people with diabetes Health Psychol 2008 27 1S S73 S82 18248108

- Tsenkova VK Love GD Singer BH Ryff CD Coping and positive affect predict longitudinal change in glycosylated hemoglobin Health Psychol 2008 27 2S S163 S171 18377158

- Cummings DM Kirian K Howard G Consequences of comorbidity of elevated stress and/or depressive symptoms and incident cardiovascular outcomes in diabetes: results from the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study Diabetes Care 2016 39 1 101 109 26577418

- Katon WJ Rutter C Simon G The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes Diabetes Care 2005 28 11 2668 2672 16249537

- Lin EHB Heckbert SR Rutter CM Depression and increased mortality in diabetes: unexpected causes of death Ann Fam Med 2009 7 5 414 421 19752469

- Park M Katon WJ Wolf FM Depression and risk of mortality in individuals with diabetes: a meta-analysis and systematic review Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013 35 3 217 225 23415577

- Moran C Phan TG Chen J Brain atrophy in type 2 diabetes: regional distribution and influence on cognition Diabetes Care 2013 36 12 4036 4042 23939539

- Novak V Last D Alsop DC Cerebral blood flow velocity and periventricular white matter hyperintensities in type 2 diabetes Diabetes Care 2006 29 7 1529 1534 16801574

- Tiemeier H Bakker SLM Hofman A Koudstaal PJ Breteler MMB Cerebral haemodynamics and depression in the elderly J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002 73 1 34 39 12082042

- Katon WJ Lin EHB Williams LH Comorbid depression is associated with an increased risk of dementia diagnosis in patients with diabetes: a prospective cohort study J Gen Intern Med 2010 25 5 423 429 20108126

- Swardfager W MacIntosh BJ Depression, type 2 diabetes, and poststroke cognitive impairment Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2017 31 1 48 55 27364648

- Raison CL Miller AH When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders Am J Psychiatry 2003 160 9 1554 1565 12944327

- Pruzin JJ Schneider JA Capuano AW Diabetes, hemoglobin A1C, and regional Alzheimer disease and infarct pathology Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2017 31 1 41 47 27755004

- Katon W Von Korff M Ciechanowski P Behavioral and clinical factors associated with depression among individuals with diabetes Diabetes Care 2004 27 4 914 920 15047648

- Schmitz N Deschênes SS Burns RJ Cardiometabolic dysregulation and cognitive decline: potential role of depressive symptoms Br J Psychiatry 2018 212 2 96 102 29436332

- Polonsky WH Fisher L Earles J Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale Diabetes Care 2005 28 626 631 15735199