Abstract

Urinary tract infections are more common, more severe, and carry worse outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. They are also more often caused by resistant pathogens. Various impairments in the immune system, poor metabolic control, and incomplete bladder emptying due to autonomic neuropathy may all contribute to the enhanced risk of urinary tract infections in these patients. The new anti-diabetic sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors have not been found to significantly increase the risk of symptomatic urinary tract infections. Symptoms of urinary tract infection are similar to patients without diabetes, though some patients with diabetic neuropathy may have altered clinical signs. Treatment depends on several factors, including: presence of symptoms, severity of systemic symptoms, if infection is localized in the bladder or also involves the kidney, presence of urologic abnormalities, accompanying metabolic alterations, and renal function. There is no indication to treat diabetic patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Further studies are needed to improve the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes and urinary tract infections.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by variable degrees of insulin resistance, impaired insulin secretion, and increased glucose production. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus are at increased risk of infections, with the urinary tract being the most frequent infection site.Citation1–Citation4 Various impairments in the immune system,Citation5,Citation6 in addition to poor metabolic control of diabetes,Citation7,Citation8 and incomplete bladder emptying due to autonomic neuropathyCitation9,Citation10 may all contribute in the pathogenesis of urinary tract infections (UTI) in diabetic patients. Factors that were found to enhance the risk for UTI in diabetics include age, metabolic control, and long term complications, primarily diabetic nephropathy and cystopathy.Citation11

The spectrum of UTI in these patients ranges from asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) to lower UTI (cystitis), pyelonephritis, and severe urosepsis. Serious complications of UTI, such as emphysematous cystitis and pyelonephritis, renal abscesses and renal papillary necrosis, are all encountered more frequently in type 2 diabetes than in the general population.Citation12,Citation13 Type 2 diabetes is not only a risk factor for community-acquired UTI but also for health care-associated UTI,Citation14 catheter-associated UTI,Citation15 and post-renal transplant-recurrent UTI.Citation16 In addition, these patients are more prone to have resistant pathogens as the cause of their UTI, including extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive Enterobacteriaceae,Citation17 fluoroquinolone-resistant uropathogens,Citation18 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,Citation19 and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci.Citation20 Type 2 diabetes is also a risk factor for fungal UTI, mostly caused by Candida.Citation21 Diabetes is also associated with worse outcomes of UTI, including longer hospitalizations and increased mortality.

The increased risk of UTI among diabetic patients, coupled with the increase in the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus worldwide in recent years, may impose a substantial burden on medical costs.Citation22 In addition, the high rates of antibiotic prescription, including broad-spectrum antibiotics, for UTI in these patients may further induce the development of antibiotic-resistant urinary pathogens.Citation23

In this review, we will focus on the various types of UTI in this population, their frequency, risk factors, diagnosis, prognosis, and when and what treatment should be administered.

The risk of UTI in type 2 diabetes mellitus

All types of UTI are more frequent in patients with type 2 diabetes. Various studies have reported the overall incidence of UTI among these patients. An observational study of all patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK general practice research database found that the incidence rate of UTI was 46.9 per 1,000 person-years among diabetic patients and 29.9 for patients without diabetes.Citation24 Women with previously diagnosed diabetes had a higher risk of UTI than those with recently diagnosed diabetes (within 6 months) (91.9/1,000 person-years; 95% confidence interval [CI] 84.3–99.4, vs 70.5/1,000 person-years; 95% CI 68.2–72.8).Citation24 A cohort study of over 6,000 patients enrolled in ten clinical trials found an incidence rate of 91.5 per 1,000 person-years in women and 28 per 1,000 person-years in men, and a cumulative incidence of 2% during 6 months.Citation25 A recent American study performed on a health service data base with more than 70,000 patients with type 2 diabetes found that 8.2% were diagnosed with UTI during 1 year (12.9% of women and 3.9% of men, with incidence increasing with age).Citation22 Another American database study from 2014 found that a UTI diagnosis was more common in men and women with diabetes than in those without diabetes (9.4% vs 5.7%, respectively) among 89,790 matched pairs of patients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus.Citation26

ASB is more prevalent in women, due to a short urethra that is in proximity to the warm, moist, vulvar, and perianal areas that are colonized with enteric bacteria. ASB increases with age, and is also associated with urinary tract abnormalities or foreign bodies (urethral catheters, stents, etc).Citation27,Citation28 Many studies have reported an increased prevalence of ASB in diabetic patients, with estimates ranging from 8%–26%.Citation7,Citation8,Citation29,Citation30 A meta- analysis of 22 studies, published in 2011, found a point prevalence of 12.2% of ASB among diabetic patients versus 4.5% in healthy control subjects.Citation31 The point prevalence of ASB was higher both in women and men, was higher in patients with a longer duration of diabetes, and was not associated with glycemic status, as evaluated by glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).Citation31 A recent prospective study of inpatients at an Indian hospital found a 30% prevalence rate of ASB among diabetic patients.Citation32

Pyelonephritis was found to be 4.1 times more frequent in pre-menopausal diabetic women than in women without diabetes in a case control study of a Washington State health group.Citation33 In a Canadian study, diabetic women (type 1 and 2, identified by receipt of oral hypoglycemic or insulin therapy) were 6–15 times more frequently hospitalized (depending upon age group) for acute pyelonephritis than non-diabetic women, and diabetic men were hospitalized 3.4–17 times more than non-diabetic men.Citation34 A Danish study reported patients with diabetes mellitus were 3 times more likely to be hospitalized with pyelonephritis, as compared to subjects without diabetes.Citation35

In men, risk of acute bacterial prostatitis, prostatic abscess, progression to chronic prostatitis, and infections following prostatic manipulations, such as trans-rectal prostate biopsy, is increased in patients with diabetes mellitus.Citation36,Citation37

Pathogenesis, risk factors, and pathogens of UTI in patients with diabetes

Pathogenesis and risk factors

Multiple potential mechanisms unique to diabetes may contribute to the increased risk of UTI in diabetic patients.Citation38 Higher glucose concentrations in urine may promote the growth of pathogenic bacteria.Citation8,Citation39 However, several studies did not find an association between HbA1c level, which serves as a proxy for glycosuria, and risk of UTI among diabetic patients; also, sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, which increase glycosuria, were not found to increase the rate of UTI.Citation3,Citation40 High renal parenchymal glucose levels create a favorable environment for the growth and multiplication of microorganisms, which might be one of the precipitating factors of pyelonephritis and renal complications such as emphysematous pyelonephritis.Citation30,Citation41 Various impairments in the immune system, including humoral, cellular, and innate immunity may contribute in the pathogenesis of UTI in diabetic patients.Citation5,Citation6,Citation42 Lower urinary interleukin-6 and -8 levels were found in patients with diabetes with ASB, compared to those without diabetes with ASB.Citation41 Autonomic neuropathy involving the genitourinary tract results in dysfunctional voiding and urinary retention, decreasing physical bacterial clearance through micturition, thereby facilitating bacterial growth.Citation9,Citation10,Citation43 Bladder dysfunction occurs in 26%–85% of diabetic women, depending on age extent of neuropathy and duration of diabetic disease,Citation44 and thus should be considered in all diabetic patients with UTI.

A paper from Saudi Arabia found the following factors to be associated with an increased risk of UTI among patients with diabetes: female sex (relative risk [RR] 6.1), hypertension (RR 1.2), insulin therapy (RR 1.4), body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 (RR 1.72), and nephropathy (RR 1.42).Citation45 The release of new anti-diabetic sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, which increase glycosuria, caused concern of a possible increase in UTIs,Citation46 though a recent meta-analysis found similar incidences of UTI in patients treated with canagliflozin as compared with control groups.Citation47 Dapagliflozin was associated with a slight increase in UTI (4.8% vs 3.7%), though no increase in pyelonephritis was found.Citation48

Pathogens

The most common pathogens isolated from urine of diabetic patients with UTI are Escherichia coli, other Enterobacteriaceae such as Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Enterobacter spp., and Enterococci.Citation49 Patients with diabetes are more prone to have resistant pathogens as the cause of their UTI, including extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive Enterobacteriaceae,Citation17,Citation50 fluoroquinolone-resistant uropathogens,Citation18 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae,Citation19 and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci.Citation20 This might be due to several factors, including multiple courses of antibiotic therapy that are administered to these patients, frequently for asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic UTI, and increased incidence of hospital-acquired and catheter-associated UTI, which are both associated with resistant pathogens. Type 2 diabetes is also a risk factor for fungal UTI.Citation21

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of UTI should be suspected in any diabetic patient with symptoms consistent with UTI. These symptoms are: frequency, urgency, dysuria, and suprapubic pain for lower UTI; and costovertebral angle pain/tenderness, fever, and chills, with or without lower urinary tract symptoms for upper UTI. Diabetic patients are prone to have a more severe presentation of UTI,Citation12 though some patients with diabetic neuropathy may have altered clinical signs. A recent multi-center study from South Korea of women with community-acquired acute pyelonephritis found that significantly fewer of the diabetic patients had flank pain, costovertebral angle tenderness, and symptoms of lower UTI as compared to non-diabetic women.Citation51 Patients with type 2 diabetes and UTI might present with hypo- or hyperglycemia, non-ketotic hyperosmolar state, or even ketoacidosis, all of which prompt a rapid exclusion of infectious precipitating factors, including UTI.Citation8,Citation52

Once the diagnosis of UTI is suspected, a midstream urine specimen should be examined for the presence of leukocytes, as pyuria is present in almost all cases of UTI.Citation8,Citation53 Pyuria can be detected either by microscopic examination (defined as ≥10 leukocytes/mm3), or by dipstick leukocyte esterase test (sensitivity of 75%–96% and specificity of 94%–98%, as compared with microscopic examination, which is the gold standard).Citation54 An absence of pyuria on microscopic assessment can suggest colonization, instead of infection, when there is bacteriuria.Citation54 Microscopic examination allows for visualizing bacteria in urine. A dipstick also tests for the presence of urinary nitrite. A positive test indicates the presence of bacteria in urine, while a negative test can be the product of low count bacteriuria or bacterial species that lack the ability to reduce nitrate to nitrite (mostly Gram-positive bacteria).Citation55 Microscopic or macroscopic hematuria is sometimes present, and proteinuria is also a common finding.Citation56

A urine culture should be obtained in all cases of suspected UTI in diabetic patients, prior to initiation of treatment. The only exceptions are cases of suspected acute cystitis in diabetic women who do not have long term complications of diabetes, including diabetic nephropathy, or any other complicating urologic abnormality.Citation8 However, even in these cases, if empiric treatment fails or there is recurrence within 1 month of treatment, a culture should be obtained. The preferred method of obtaining a urine culture is from voided, clean-catch, midstream urine.Citation56 When such a specimen cannot be collected, such as in patients with altered sensorium or neurologic/urologic defects that hamper the ability to void, a culture may be obtained through a sterile urinary catheter inserted by strict aseptic technique, or by suprapubic aspiration. In patients with long-term indwelling catheters, the preferred method of obtaining a urine specimen for culture is replacing the catheter and collecting a specimen from the freshly placed catheter, due to formation of biofilm on the catheter.Citation57,Citation58

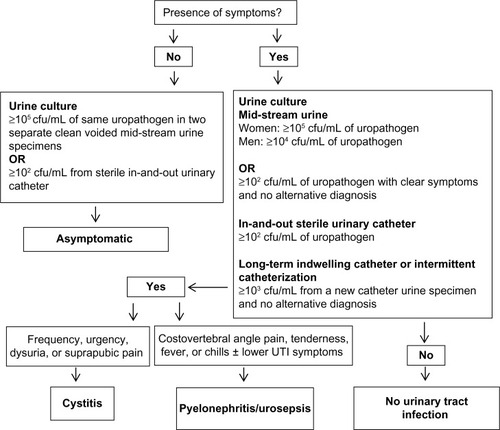

The definition of a positive urine culture

The definition of a positive urine culture depends on the presence of symptoms and the method of urinary specimen collection, as follows and as depicted in . For the diagnosis of cystitis or pyelonephritis in women, a midstream urine count ≥105 cfu/mL is considered diagnostic of UTI.Citation59 However, in diabetic women with good metabolic control and without long-term complications who present with acute uncomplicated cystitis, quantitative counts <105 colony-forming units [cfu]/mL are isolated from 20%–25% of premenopausal women and about 10% of postmenopausal women.Citation8 Only 5% of patients with acute pyelonephritis have lower quantitative counts isolated.Citation8 Lower bacterial counts are more often encountered in patients already on antimicrobials and are thought to result from impaired renal concentrating ability or diuresis, which limits the dwell time of urine in the bladder.Citation8,Citation60 Thus, in symptomatic women with pyuria and lower midstream urine counts (≥102 cfu/mL), a diagnosis of UTI should be suspected.

Figure 1 Flow chart for the diagnosis of urinary tract infection in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

For the diagnosis of UTI in men, a midstream urine colony count of ≥104 cfu/mL is indicative. However, when coli-form bacteria (eg, E. coli) are isolated, lower colony counts might also represent significant bacteriuria.Citation61

From an in-and-out catheter specimen, growth of ≥102 cfu/mL, in the presence of urinary symptoms, is diagnostic of UTI.Citation62 In patients with long-term indwelling catheters or intermittent catheterization, growth of ≥103 cfu/mL from a single new catheter urine specimen indicates UTI; in a midstream voided urine specimen from a patient whose urethral, suprapubic, or condom catheter that has been removed within the previous 48 hours, and has no other identified source of infection, similar numbers would also indicate UTI.Citation57

The diagnosis of ASB can be made based on a growth of ≥105 cfu/mL of the same uropathogen (up to two pathogens) in two consecutive clean voided mid-stream urine specimens, or ≥102 cfu/mL in a specimen collected through a sterile in-and-out urinary catheter, in the absence of signs or symptoms of urinary infection.Citation63 As many as 70% of diabetic women with ASB have accompanying pyuria. Thus, the presence of pyuria is not useful for differentiating between symptomatic or asymptomatic UTI.Citation64

Outcomes and complications

Outcomes

Patients with diabetes have worse outcomes of UTI than those without diabetes.Citation13,Citation65 Diabetes was found to be risk factor for early clinical failure after 72 hours of antibiotic treatment in women with community-onset acute pyelonephritis.Citation66 Diabetes is also associated with longer hospitalization, bacteremia, azotemia, and septic shock in patients with UTI.Citation12 Mortality from UTI is 5 times higher in patients with diabetes aged 65 and older, as compared to elderly control patients.Citation12 Relapse and reinfection are also more common in diabetic patients (7.1% and 15.9%, respectively, vs 2.0% and 4.1%, respectively, in women without diabetes) according to a Dutch study of diabetic women with UTI.Citation67 Another study also found higher rates of recurrence of UTI in patients with type 2 diabetes of 1.6%, vs 0.6% in non-diabetic patients.Citation26

Complications

Over 90% of cases of emphysematous pyelonephritisCitation41 and 67% of episodes of emphysematous cystitisCitation68 occur in patients with diabetes mellitus. Renal and perinephric abscesses occur far more frequently in diabetic patients as well.Citation13 Urosepsis and bacteremia are also more frequent in patients with diabetes. A Greek study from 2009 found that within a group of hospitalized elderly patients with acute pyelonephritis, 30.7% of patients with diabetes had bacteremia compared to 11% of patients without diabetes.Citation12

Management

Treatment of UTI in patients with type 2 diabetes depends on several factors, including: presence of symptoms, if infection is localized in the bladder (lower UTI) or also involves the kidney (upper UTI), presence of urologic abnormalities, severity of systemic symptoms, accompanying metabolic alterations, and renal function.Citation8 As a general rule, treatment of UTI in diabetic patients is similar to that of UTI in non-diabetic patients. Antibiotic choice should also be guided by local susceptibility patterns of uropathogens. Treatment should also involve correction of metabolic complications caused by the infectious process. First-line treatment options for various types of UTI are detailed in .

Table 1 First-line antibiotic treatment of urinary tract infection in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

There is no indication to treat ASB in diabetic patients.Citation69 Though earlier studies raised the concern that bacteriuria may be associated with progression to symptomatic UTI and with deteriorating renal function in patients with diabetes,Citation7,Citation70 later studies found that diabetic women with ASB do not have an increased risk for a faster decline in renal function,Citation71 and that there are no short- or long-term benefits from the treatment of ASB in diabetic women.Citation72 A placebo-controlled, randomized prospective study of 105 women with diabetes mellitus found that during a mean follow-up period of 27 months, antibiotic treatment did not affect the rate of symptomatic UTI, pyelonephritis, or hospitalizations for UTI.Citation72 A study from 2006 found that ASB by itself is not associated with an increased rate of progression to renal impairment or long term complications during 6 years of follow-up in patients with diabetes.Citation71 Another study that followed diabetic women with ASB for up to 3 years found that bacteriuria persists or recurs in most women, is benign, and seldom permanently eradicable.Citation73 All the above studies found that women with ASB received multiple courses of antibiotic therapy, which may result in increased antibiotic resistance.

Acute cystitis in women with good glucose control and without long-term diabetes complications may be managed as uncomplicated lower UTI,Citation8 and treated empirically with one of the following:Citation74 nitrofurantoin 100 mg three times daily for 5 days, fosfomycin trometamol 3 g single dose, or trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole 960 mg twice daily for 3 days (can be administered empirically only if resistance prevalence is known to be less than 20% and medication was not used in previous 3 months). Quinolones and β-lactams are other, alternative second-line treatments. Treatment should be tailored according to culture results, if obtained.

Other cases of lower UTI in diabetic patients are mostly considered complicated lower UTI and should be treated with antibiotics. In patients with a chronic indwelling catheter, UTI prompts exchange of the urinary catheter.Citation57 The wide variety of potential infecting organisms and increased likelihood of resistance make uniform recommendations for empirical therapy problematic.Citation75 Whenever possible, antimicrobial therapy should be delayed pending results of urine culture and organism susceptibility, so specific therapy can be directed at the known pathogen. Therapeutic options include fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and β-lactames ().

Pyelonephritis in patients with type 2 diabetes may be treated with oral antibiotics in patients with mild–moderate symptoms,Citation74 with no alterations in gastrointestinal absorption, such as gastric emptying impairment or chronic diarrhea caused by diabetic neuropathy. However, diabetic patients with severe symptoms, hemodynamic instability, metabolic alterations, or symptoms that preclude administration of oral medication (nausea, vomiting) should be hospitalized for initial intravenous antibiotic therapy.Citation8,Citation74 Treatment with empiric antibiotics, using broad-spectrum cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, piperacillin–tazobactam, or carbapenems should be initiated ().Citation74,Citation76 Patients presenting with severe sepsis or those known to harbor resistant uropathogens or that have received multiple antibiotic courses should receive broad- spectrum coverage, guided by recent urinary cultures. Treatment should be tailored when culture results are available.

Recommended duration of antibiotic treatment for UTI is depicted in , and is similar to that of non-diabetic patients. Though some argue that patients with diabetes mellitus should receive longer antibiotic treatment than patients without diabetes mellitus,Citation77 randomized controlled trials are lacking.

Emphysematous pyelonephritis was historically treated by nephrectomy or open drainage, along with systemic antibiotics. In a more recent report, successful management with systemic antibiotics together with percutaneous catheter drainage of gas and purulent material, as well as relief of urinary tract obstruction, if present, has been described.Citation78

The choice of antibiotics in patients with diabetes mellitus should also take into consideration possible drug interactions between antimicrobials and antidiabetics or antihypertensive agents, and impaired glucose homeostasis that may be caused by certain antibiotics.Citation79 Dosage adjustment is required in diabetic patients with renal impairment for some antimicrobials agents. Due to their nephrotoxic effect, aminoglycosides should be used with caution in patients with renal failure, and nitrofurantoin should be avoided in patients with renal failure, due to drug accumulation that is associated with peripheral neuropathy.Citation80

Management of recurrent episodes of UTI is similar to non-diabetic patients.Citation8 In young women without diabetic complications, post-coital or daily low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis may be offered.Citation74 In patients with renal failure, complex urologic abnormalities, or highly resistant bacteria, long-term antibiotic prophylaxis is less effective.Citation8 In patients requiring catheterization due to incomplete bladder voiding, intermittent catheterization is preferred over a chronic indwelling catheter.Citation57

Conclusion

UTI are common among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. In these patients, UTI are more severe, caused by more resistant pathogens, and is associated with worse outcomes than in patients without diabetes. Treatment should be offered only to symptomatic cases, as ASB is a common finding, and antibiotic treatment in such cases serves mostly to increase bacterial resistance. Treatment should be tailored according to severity of infection and culture results. Further studies are needed to improve the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes and UTI.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PattersonJEAndrioleVTBacterial urinary tract infections in diabetesInfect Dis Clin North Am1997113735 7509378933

- JoshiNCaputoGMWeitekampMRKarchmerAWInfections in patients with diabetes mellitusN Engl J Med1999341251906 191210601511

- BoykoEJFihnSDScholesDAbrahamLMonseyBRisk of urinary tract infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria among diabetic and nondiabetic postmenopausal womenAm J Epidemiol20051616557 56415746472

- ShahBRHuxJEQuantifying the risk of infectious diseases for people with diabetesDiabetes Care2003262510 51312547890

- DelamaireMMaugendreDMorenoMLe GoffMCAllannicHGenetetBImpaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patientsDiabet Med199714129 349017350

- ValeriusNHEffCHansenNENeutrophil and lymphocyte function in patients with diabetes mellitusActa Med Scand19822116463 4676981286

- GeerlingsSEStolkRPCampsMJAsymptomatic bacteriuria can be considered a diabetic complication in women with diabetes mellitusAdv Exp Med Biol2000485309 31411109121

- FünfstückRNicolleLEHanefeldMNaberKGUrinary tract infection in patients with diabetes mellitusClin Nephrol201277140 4822185967

- TruzziJCAlmeidaFMNunesECSadiMVResidual urinary volume and urinary tract infection – when are they linked?J Urol20081801182 18518499191

- HoskingDJBennettTHamptonJRDiabetic autonomic neuropathyDiabetes197827101043 1055359387

- BrownJSWessellsHChancellorMBUrologic complications of diabetesDiabetes Care2005281177 18515616253

- KofteridisDPPapadimitrakiEMantadakisEEffect of diabetes mellitus on the clinical and microbiological features of hospitalized elderly patients with acute pyelonephritisJ Am Geriatr Soc200957112125 212820121956

- MnifMFKamounMKacemFHComplicated urinary tract infections associated with diabetes mellitus: pathogenesis, diagnosis and managementIndian J Endocrinol Metab2013173442 44523869299

- DattaPRaniHChauhanRGombarSChanderJHealth-care-associated infections: risk factors and epidemiology from an intensive care unit in Northern IndiaIndian J Anaesth201458130 3524700896

- LeeJHKimSWYoonBIHaUSSohnDWChoYHFactors that affect nosocomial catheter-associated urinary tract infection in intensive care units: 2-year experience at a single centerKorean J Urol201354159 6523362450

- LimJHChoJHLeeJHRisk factors for recurrent urinary tract infection in kidney transplant recipientsTransplant Proc20134541584 158923726625

- InnsTMillershipSTeareLRiceWReacherMService evaluation of selected risk factors for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Escherichia coli urinary tract infections: a case-control studyJ Hosp Infect2014882116 11925146227

- WuYHChenPLHungYPKoWCRisk factors and clinical impact of levofloxacin or cefazolin nonsusceptibility or ESBL production among uropathogens in adults with community-onset urinary tract infectionsJ Microbiol Immunol Infect2014473197 20323063776

- SchechnerVKotlovskyTKazmaMAsymptomatic rectal carriage of blaKPC producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: who is prone to become clinically infected?Clin Microbiol Infect2013195451 45622563800

- Papadimitriou-OlivgerisMDrougkaEFligouFRisk factors for enterococcal infection and colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci in critically ill patientsInfection20144261013 102225143193

- SobelJDFisherJFKauffmanCANewmanCACandida urinary tract infections – epidemiologyClin Infect Dis201152Suppl 6S433 S43621498836

- YuSFuAZQiuYDisease burden of urinary tract infections among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in the USJ Diabetes Complications2014285621 62624929797

- VenmansLMHakEGorterKJRuttenGEIncidence and antibiotic prescription rates for common infections in patients with diabetes in primary care over the years 1995 to 2003Int J Infect Dis2009136e344 e35119208491

- HirjiIGuoZAnderssonSWHammarNGomez-CamineroAIncidence of urinary tract infection among patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD)J Diabetes Complications2012266513 51622889712

- HammarNFarahmandBGranMJoelsonSAnderssonSWIncidence of urinary tract infection in patients with type 2 diabetes. Experience from adverse event reporting in clinical trialsPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf201019121287 129220967764

- FuAZIglayKQiuYEngelSShankarRBrodoviczKRisk characterization for urinary tract infections in subjects with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetesJ Diabetes Complications2014286805 81025161100

- ColganRNicolleLEMcGloneAHootonTMAsymptomatic bacteriuria in adultsAm Fam Physician2006746985 99017002033

- NicolleLEAsymptomatic bacteriuriaCurr Opin Infect Dis201427190 9624275697

- ZhanelGGNicolleLEHardingGKPrevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria and associated host factors in women with diabetes mellitus. The Manitoba Diabetic Urinary Infection Study GroupClin Infect Dis1995212316 3228562738

- SchneebergerCKazemierBMGeerlingsSEAsymptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infections in special patient groups: women with diabetes mellitus and pregnant womenCurr Opin Infect Dis2014271108 11424296584

- RenkoMTapanainenPTossavainenPPokkaTUhariMMeta-analysis of the significance of asymptomatic bacteriuria in diabetesDiabetes Care2011341230 23520937688

- AswaniSMChandrashekarUShivashankaraKPruthviBClinical profile of urinary tract infections in diabetics and non-diabeticsAustralas Med J20147129 3424567764

- ScholesDHootonTMRobertsPLGuptaKStapletonAEStammWERisk factors associated with acute pyelonephritis in healthy womenAnn Intern Med2005142120 2715630106

- NicolleLEFriesenDHardingGKRoosLLHospitalization for acute pyelonephritis in Manitoba, Canada, during the period from 1989 to 1992; impact of diabetes, pregnancy, and aboriginal originClin Infect Dis19962261051 10568783709

- BenfieldTJensenJSNordestgaardBGInfluence of diabetes and hyperglycaemia on infectious disease hospitalisation and outcomeDiabetologia2007503549 55417187246

- BiloHJSusceptibility to infection in patients with diabetes mellitusNed Tijdschr Geneeskd200615010533 534 Dutch16566414

- WenSCJuanYSWangCJEmphysematous prostatic abscess: case series study and reviewInt J Infect Dis2012165e344 e34922425493

- ChenSLJacksonSLBoykoEJDiabetes mellitus and urinary tract infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis and proposed studies in animal modelsJ Urol20091826 SupplS51 S5619846134

- WangMCTsengCCWuABBacterial characteristics and glycemic control in diabetic patients with Escherichia coli urinary tract infectionJ Microbiol Immunol Infect201346124 2922572000

- BoykoEJFihnSDScholesDChenCLNormandEHYarbroPDiabetes and the risk of acute urinary tract infection among postmenopausal womenDiabetes Care200225101778 178312351477

- Soo ParkBLeeSJWha KimYSik HuhJIl KimJChangSGOutcome of nephrectomy and kidney-preserving procedures for the treatment of emphysematous pyelonephritisScand J Urol Nephrol2006404332 33816916776

- GeerlingsSEBrouwerECVan KesselKCGaastraWStolkRPHoepelmanAICytokine secretion is impaired in women with diabetes mellitusEur J Clin Invest20003011995 100111114962

- KaplanSATeAEBlaivasJGUrodynamic findings in patients with diabetic cystopathyJ Urol19951532342 3447815578

- Frimodt-MøllerCDiabetic cystopathy: epidemiology and related disordersAnn Intern Med1980922 Pt 2318 3217356221

- Al-RubeaanKAMoharramOAl-NaqebDHassanARafiullahMRPrevalence of urinary tract infection and risk factors among Saudi patients with diabetesWorld J Urol2013313573 57822956119

- NicolleLECapuanoGFungAUsiskinKUrinary tract infection in randomized phase III studies of canagliflozin, a sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitorPostgrad Med201412617 1724393747

- YangXPLaiDZhongXYShenHPHuangYLEfficacy and safety of canagliflozin in subjects with type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysisEur J Clin Pharmacol201470101149 115825124541

- PtaszynskaAJohnssonKMParikhSJde BruinTWApanovitchAMListJFSafety profile of dapagliflozin for type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of clinical studies for overall safety and rare eventsDrug Saf20143710815 82925096959

- GeerlingsSEMeilandRvan LithECBrouwerECGaastraWHoepelmanAIAdherence of type 1-fimbriated Escherichia coli to uroepithelial cells: more in diabetic women than in control subjectsDiabetes Care20022581405 140912145242

- ColodnerRRockWChazanBRisk factors for the development of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in nonhospitalized patientsEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis2004233163 16714986159

- KimYWieSHChangUIComparison of the clinical characteristics of diabetic and non-diabetic women with community-acquired acute pyelonephritis: a multicenter studyJ Infect2014693244 25124854421

- CartonJAMaradonaJANuñoFJFernandez-AlvarezRPérez-GonzalezFAsensiVDiabetes mellitus and bacteraemia: a comparative study between diabetic and non-diabetic patientsEur J Med199215281 2871341610

- StammWEMeasurement of pyuria and its relation to bacteriuriaAm J Med1983751B53 586349345

- LittlePTurnerSRumsbyKDipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative studyHealth Technol Assess20091319iii ivix xi1 7319364448

- GiesenLGCousinsGDimitrovBDvan de LaarFAFaheyTPredicting acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signsBMC Fam Pract2010117820969801

- BennettJEDoliRBlaserMJMandell, Douglas, and Bennetts Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases8th edElsevier Inc2015

- HootonTMBradleySFCardenasDDInfectious Diseases Society of AmericaDiagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of AmericaClin Infect Dis2010505625 66320175247

- KuninCMChinQFChambersSIndwelling urinary catheters in the elderly: relation of “catheter life” to formation of encrustations in patients with and without blocked cathetersAm J Med198782405 4113826097

- KassEHAsymptomatic infections of the urinary tractTrans Assoc Am Physicians19566956 6413380946

- KuninCMWhiteLVHuaTHA reassessment of the importance of “low-count” bacteriuria in young women with acute urinary symptomsAnn Intern Med19931196454 4608357110

- RubinRHShapiroEDAndrioleVTDavisRJStammWEEvaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of urinary tract infection. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Food and Drug AdministrationClin Infect Dis199215Suppl 1S216 S2271477233

- StarkRPMakiDGBacteriuria in the catheterized patient. What quantitative level of bacteriuria is relevant?N Engl J Med19843119560 5646749229

- RazRAsymptomatic bacteriuria. Clinical significance and managementInt J Antimicrob Agents200322Suppl 245 4714527770

- ZhanelGGHardingGKNicolleLEAsymptomatic bacteriuria in patients with diabetes mellitusRev Infect Dis1991131150 1542017615

- PertelPEHaverstockDRisk factors for a poor outcome after therapy for acute pyelonephritisBJU Int2006981141 14716831159

- WieSHKiMKimJClinical characteristics predicting early clinical failure after 72 h of antibiotic treatment in women with community-onset acute pyelonephritis: a prospective multicentre studyClin Microbiol Infect20142010721 729

- GorterKJHakEZuithoffNPHoepelmanAIRuttenGERisk of recurrent acute lower urinary tract infections and prescription pattern of antibiotics in women with and without diabetes in primary careFam Pract2010274379 38520462975

- ThomasAALaneBRThomasAZRemerEMCampbellSCShoskesDAEmphysematous cystitis: a review of 135 casesBJU Int2007100117 2017506870

- NicolleLEBradleySColganRRiceJCSchaefferAHootonTMInfectious Diseases Society of AmericaAmerican Society of ephrologyAmerican Geriatric SocietyInfectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adultsClin Infect Dis2005405643 65415714408

- BatallaMABalodimosMCBradleyRFBacteriuria in diabetes mellitusDiabetologia197175297 3015134251

- MeilandRGeerlingsSEStolkRPNettenPMSchneebergerPMHoepelmanAIAsymptomatic bacteriuria in women with diabetes mellitus: effect on renal function after 6 years of follow-upArch Intern Med2006166202222 222717101940

- NicolleLEZhanelGGHardingGKMicrobiological outcomes in women with diabetes and untreated asymptomatic bacteriuriaWorld J Urol200624161 6516389540

- HardingGKZhanelGGNicolleLECheangMManitoba Diabetes Urinary Tract Infection Study GroupAntimicrobial treatment in diabetic women with asymptomatic bacteriuriaN Engl J Med2002347201576 158312432044

- GuptaKHootonTMNaberKGInfectious Diseases Society of America; European Society for Microbiology and Infectious DiseasesInternational clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious DiseasesClin Infect Dis2011525e103 e12021292654

- DielubanzaEJMazurDJSchaefferAJManagement of non-catheter-associated complicated urinary tract infectionInfect Dis Clin North Am2014281121 13424484579

- NicolleLEUncomplicated urinary tract infection in adults including uncomplicated pyelonephritisUrol Clin North Am20083511 1218061019

- GeerlingsSEUrinary tract infections in patients with diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatmentInt J Antimicrob Agents200831Suppl 1S54 718054467

- LinWRChenMHsuJMWangCHEmphysematous pyelonephritis: patient characteristics and management approachUrol Int201493129 3324135457

- ChanJCCockramCSCritchleyJADrug-induced disorders of glucose metabolism. Mechanisms and managementDrug Saf1996152135 1578884164

- MunarMYSinghHDrug dosing adjustments in patients with chronic kidney diseaseAm Fam Physician200775101487 149617555141