Abstract

With the increasing obesity rates in Western countries, an effective lifestyle intervention for fat reduction and metabolic benefits is needed. High-intensity intermittent exercise (HIIE), Mediterranean eating habits (Mediet), and fish oil (ω-3) consumption positively impact metabolic health and adiposity, although the combined effect has yet to be determined. A 12-week lifestyle intervention on adiposity, insulin resistance, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels of young overweight women was administered. Thirty women with a body mass index of 26.6±0.5 kg/m2, blood pressure of 114/66±1.9/1.5 mmHg, and age of 22±0.8 years were randomly assigned to either an intervention group receiving Mediet advice, daily ω-3 supplementation, and HIIE 3 days/week for 12 weeks or a control group. The group receiving Mediet advice, daily ω-3 supplementation, and HIIE experienced a significant reduction in total body fat mass (P<0.001), abdominal adiposity (P<0.05), waist circumference (P<0.001), systolic blood pressure (P<0.05), fasting plasma insulin (P<0.05), IL-6 (P<0.001), and triglycerides (P<0.05). The greatest decreases in fasting plasma insulin (P<0.05) and IL-6 (P<0.001) occurred by week 6 of the intervention. Significant improvements in eating habits (P<0.05) and aerobic fitness (P<0.001) were also found following the intervention. A multifaceted 12-week lifestyle program comprising a Mediet, ω-3 supplementation, and HIIE induced significant improvements in fat loss, aerobic fitness, and insulin and IL-6 levels, positively influencing metabolic health.

Keywords:

Introduction

In the US, 23% of American adults have been diagnosed with metabolic syndrome (MetS),Citation1,Citation2 whereas in Australia the MetS prevalence is 29%.Citation3 Factors causing MetS are complex but include a physically inactive lifestyle, an unhealthy diet made up of saturated fat and processed foods, and inherited influences.Citation1 MetS is considered a significant risk factor for heart diseaseCitation1,Citation3 and type 2 diabetes (T2DM).Citation1 Clinical markers of MetS include obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, hyperinsulinemia, and elevated glucose levels.Citation3 Inflammation induced by proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-6 [IL-6]) and an elevated fasting insulin, also known as insulin resistance (IR), have been implicated as early MetS markers,Citation4 and IR has been found in young adults free of other metabolic abnormalities.Citation5

Unfortunately, regular aerobic exercise (walking and jogging) has not resulted in significant reductions in MetS criteria (fat loss), and long-duration exercise programs have poor adherence rates and are unpopular among overweight adults.Citation6 High-intensity intermittent exercise (HIIE) is an alternative exercise protocol that is short in duration, resulting in reduced subcutaneous and abdominal adiposityCitation7 and decreased IR.Citation8–Citation10 Previous research has found greater reductions in fat mass and fasting insulin following HIIE compared with steady state exerciseCitation9 in a healthy young female population at 16 weeks in MetS patients.Citation8 Thus, there is evidence to suggest that exposure to chronic HIIE produces improvements in body composition and IR, leading to possible reductions in inflammation, more specifically IL-6.

It has not been determined, however, whether the addition of diet modification to an HIIE program increases fat mass loss and metabolic health. For example, consuming a 2-year Mediterranean diet (Mediet) high in fibre, omega-3 (ω-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids, and fruits and vegetables and low in red meat and saturated and trans fats has been shown to be beneficial,Citation11,Citation12 more specifically to decrease IR and body weight.Citation13 In addition, after controlling for weight loss, inflammation declined and MetS prevalence was reduced by halfCitation13 following the intervention. The ingestion of ω-3, abundant in the Mediet in the form of fish oils, also has beneficial effects on MetS criteria.Citation14,Citation15 Studies have found significant reductions in triglycerides,Citation16 improved insulin signaling, stabilization of glucose homeostasis,Citation15 and a reduction in fat mass when ω-3 supplementation is combined with exercise.Citation17 Several aspects of the MetS may be improved by increased intake of ω-3Citation14 and adherence to the Mediet.Citation18 However, it has been suggested that a multi-intervention approach includes the adoption of a Mediet and regular exercise involvement.Citation14,Citation17,Citation19

The combined effects of HIIE, a Mediet, and ω-3 ingestion on fat mass loss and metabolic health have not been examined. Consequently, the focus of this study was to investigate the effect of the combination of HIIE, a Mediet, and ω-3 ingestion on fat mass loss, IR, and IL-6 in overweight women.

Subjects and methods

Participants

Volunteer premenopausal and recreationally active but untrained overweight women were recruited from a university population. Thirty-two participants were randomly allocated into one of two groups – fish oil, exercise, and a Mediet (FEM) or control (CON) – by picking a paper marked “FEM” or “CON” out of a hat. Age (24±1.0 years; 22±0.6 years) and body mass index (BMI) (27.6±0.8 kg/m2; 25.7±0.5 kg/m2) were similar for both groups. Approval for the study was granted by the University of New South Wales Research Ethics Committee, and all participants signed the approved informed consent prior to study commencement. Previous HIIE only studies in femalesCitation9 and malesCitation20 were conducted separately in our laboratory.

Procedures

Participants, who were advised to avoid strenuous activity and caffeine for 24 hours prior to testing, came into the laboratory after a 12-hour overnight fast. All tests were completed at the same time of day to avoid diurnal variation. Participants were screened for contraindications to exercise and regularity of their menstrual cycle, and personal/familial medical history was assessed.

Blood pressure and cardiorespiratory fitness

Resting blood pressure was assessed with a Colin Jentow monitor (Model 7000; Colin Medical, Japan) for pre- and post-test systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure levels in the laboratory. On a separate day, cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed using a TrueMax 2400 Metabolic Cart (ParvoMedics Inc., USA), and heart rate (HR) was recorded during this session using a Polar S810I telemetry system (Polar, Finland). After a 3-minute warm-up at 30 watts (W) with a set pedal frequency of 60 revolutions per minute (RPM), the initial load was set at 45 W and was increased 15 W every minute until voluntary cessation and/or pedal frequency could not be maintained. All sessions were performed on an electronically braked Monark cycle ergometer, 839E (Monark, Sweden), using a two-way breathing valve and nose clip (Hans Rudolph, USA). Due to the strenuous nature of the exercise session, not all participants achieved the criteria for VO2max,Citation21 so VO2peak was accepted as an indicant of aerobic power.

Dietary intake

All participants were asked to complete a pre- and post-24-hour diet diary recall of food consumed on 3 separate days consisting of 2 week days and 1 weekend day. The diets were analyzed using dietary analysis software (Foodworks 2007, version 5.00; Xyris Software). Women assigned to the intervention group (FEM) ate a low glycemic Mediet and ingested three 1,100 mg fish oil (ω-3) capsules per day for 12 weeks. Each capsule contained 550 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid per 1,100 mg capsule (YourHealth Group, Australia). The FEM women were given an overview of the healthy eating plan and recipes, along with a Mediterranean pyramid. After the initial diet sessions, FEM women were provided with feedback from their previous 1-day diet diary (every 3 weeks), and guidance was given for ways to progress toward the recommended Mediet. Use of a Mediet score (MDS) provided adherence information on a scale of 0 (least adherent) to 9 (total adherence).Citation22 Scoring was based on the median values calculated from mean scores for all women in the FEM group. The CON group was asked to maintain their normal dietary habits.

Body composition

Participants completed a total body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan using a Lunar Prodigy scanner (software version 7.51; GE Corporation, USA) pre- and postintervention only, as the researchers did not have access to the equipment at the 6-week time point. Therefore, body fat was also assessed at baseline, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks using bioimpedance (Tanita, Japan) in order to obtain a 6-week measurement. Total body, whole body fat, and fat-free mass were measured. Central (abdominal) adiposity through DXA was measured by a standard technique previously describedCitation23 and by trunk fat obtained from regional analysis of the standard Lunar software. All DXA assessments were conducted by a trained technician blinded to the randomized groups. Participants were tested in the fasted state with no liquid 2 hours prior, for standardization purposes. BMI was calculated by dividing weight by height squared (kg/m2). Waist circumference (WC) was measured according to the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry protocolCitation24 between the lower costal border (last rib) and the iliac crest at the narrowest point.

Exercise sessions

Women who were randomly assigned to the FEM group (n=15) completed 20 minutes of exercise (8-second sprint, 12-second recovery) on a manual cycle ergometer, 828E (Monark, Sweden), for each session three times a week for 12 weeks. The CON group was asked to maintain their normal exercise habits throughout the duration of the study. For the FEM women, the HIIE workload was set at 80%–85% of the individual’s peak HR throughout each session, with a cadence between 100 RPM and 130 RPM, and recovery was set at the same amount of resistance but at a cadence of 30 RPM. The participants’ average HR for a given HIIE session fell within their individual peak HR percent range, and intensity was increased when their HR fell below their peak HR percent range. All sessions were supervised, and participants performed a 5-minute warm-up and cool-down on the bike prior to and following each session. A rating of perceived exertionCitation25 was assessed every 5 minutes, and participants cycled to a prerecorded compact disc counting down each HIIE sprint in a 3–2–1 fashion.

Fasting blood specimens

Fasting blood (total 300 mL) was drawn at baseline and weeks 6 and 12 from an antecubital vein into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) vacutainers. Whole blood lipid profiles including triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and glucose concentrations were quantified by automated enzymatic methods (Cholestech LDX, USA). The remaining whole blood in EDTA tubes was spun immediately in a chilled centrifuge (Model Megafuge 1.0R, Heraeus, Germany) at 4°C and frozen at −86°C for later analysis.

MetS score

Based on the clinical International Diabetes Federation (IDF) definition for MetS,Citation26 the participants were given a point for each of the variables listed by the International Diabetes Federation and scored out of a total of 5.

Specimen analysis

Insulin, IL-6, and adiponectin were measured using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. The degree of enzymatic turnover of the substrate was determined by dual wavelength absorbance measurement for insulin (DSL 10-1600, USA), adiponectin (R&D DRP300, USA), and IL-6 (R&D HS600B, USA). Although C-reactive protein has clinical relevance regarding inflammation, IL-6 has been shown on a molecular level to increase levels of C-reactive protein in the liver and circulating blood.Citation27 The Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as follows: HOMA-IR = [fasting insulin (μLU/mL) × fasting blood glucose (mmol/L)]/22.5.

Statistics

Data analysis was completed with the Statistical Package for Social Science for Windows software (SPSS 18.1; USA). Student’s t-tests were used to examine differences between the two groups at baseline and on the delta score between pre- and post-testing. Body composition measurements (percent body fat, WC) from Tanita, insulin, HOMA-IR, and IL-6 (pre, week 6, and post) were analyzed by one- and two-way repeated-measures analysis with variance, and a post hoc Bonferroni test was administered. Due to skewness, adiponectin values were log transformed for analysis. Pearson correlation analysis was used to determine associations between all variables on crude and log-transformed values. Spearman’s rank order correlation was performed on values that remained skewed after log transformation. All results are expressed as mean and standard error. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Thirty-two women were recruited and 30 completed the study, with one woman unable to tolerate the ω-3 and the other lost to follow-up. No significant differences were seen at baseline between the two groups. The FEM women (n=15) had significant increases in both absolute VO2peak (15.0%, P<0.001) and relative VO2peak (17.9%, P<0.001) and a significant reduction in SBP (8%, P<0.05) following the intervention compared with the CON group ().

Table 1 Body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness before and after the 12-week lifestyle intervention

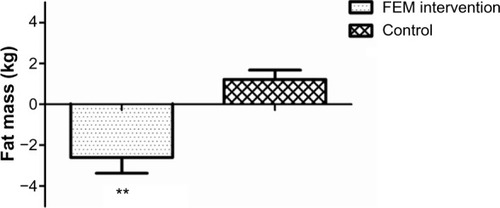

In the FEM group, total body mass (1.9 kg, 3%, P<0.001), fat mass (2.6 kg, 8.3%, P<0.001), and percent body fat (measured by bioimpedance) (F [2, 22]=7.95, P<0.05) were significantly lower ( and ) following the intervention. Abdominal adiposity (P<0.05) significantly decreased by 0.12 kg (5.0%), trunk fat by 1.2 kg (9.2%), and WC by 3.7 cm (4.7%, P<0.001) in the FEM group compared with the CON group ().

Table 2 Regional body composition measures before and after the 12-week lifestyle intervention

Figure 1 Total fat mass (kg) loss following the 12-week lifestyle intervention for the FEM intervention and control groups.

Abbreviation: FEM, intervention group receiving fish oil, exercise, and a Mediterranean diet.

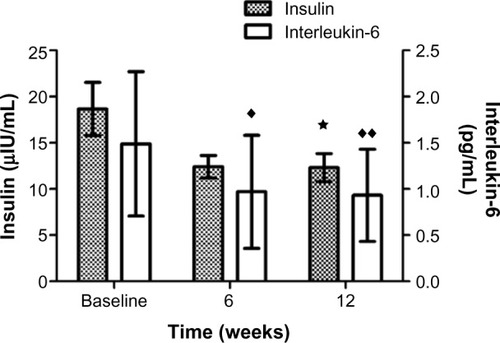

Fasting plasma insulin significantly decreased (F [1.26, 17.58] =6.72, P<0.05) in the FEM group by 34%, and a trend in fasting HOMA-IR was found (F [1.12, 15.64] =4.33, P=0.05 [36%]) in the FEM group ( and ). The reductions in insulin and IL-6 (F [2, 28] =21.09, P<0.001) levels were highly correlated with baseline values (r=−0.85, P<0.001, and r=−0.83, P<0.001), and the loss in fat mass was significantly associated with the reduction in fasting insulin (r=0.46, P<0.05). Glucose did not change significantly between groups ().

Table 3 IL-6, glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, adiponectin, and lipids before and after the 12-week lifestyle intervention

Figure 2 Insulin (μIU/mL) and interleukin-6 (pg/mL) levels for the FEM Intervention group at baseline, week 6, and week 12.

Abbreviation: FEM, fish oil, exercise, and a Mediterranean diet.

Insulin, HOMA-IR, and IL-6 at week 6 had significantly (P<0.001) decreased by 33%, 34%, and 35%, whereas no significant difference from week 6 to the post-test existed ( and ). Thus, the greatest decrease in insulin, HOMA-IR, and IL-6 occurred just 6 weeks into the 12-week intervention. No significant change in adiponectin (10%) after the intervention was found.

There was a significant decrease in triglyceride (18.1%, P<0.05; ) levels for FEM women compared with CON women, which was significantly correlated with baseline levels (r=−0.67, P=0.006, ). All other lipid levels and the score based on the MetS IDF definition were lower following FEM but not significantly different.

illustrates the average daily dietary patterns of the two groups. The FEM group significantly decreased their energy intake (P<0.05), meat, poultry, and egg (P<0.05) and cholesterol in the diet (P<0.05) and significantly increased their fruit and nut consumption (P<0.05). It was found that the FEM group significantly increased their MDS from 2.5±1.1 to 4.8±1.4 (P<0.001), representing adherence to the Mediet. No significant increase in ω-3 levels or a decrease in the omega-6 (ω-6) to ω-3 ratio in the FEM group was noted by examining diet alone. However, when the consumption of ω-3 (capsule) was added to the analysis, the ω-6:ω-3 ratio in the FEM group was significantly lower (P<0.001) at the end of the intervention compared with the CON group.

Table 4 Dietary intake before and after the 12-week lifestyle intervention

Discussion

After the intervention, the FEM women, compared with the CON women, significantly reduced their fat mass and abdominal adiposity, WC, insulin, IL-6, SBP, and triglyceride levels. The majority of change in insulin and IL-6 had occurred by week 6 of the intervention. The FEM women conformed more to a Mediet, as confirmed by an increase in MDS and a significant reduction in saturated fat. A multifaceted lifestyle program comprising a Mediet, ω-3 supplementation, and HIIE induced significant fat mass and abdominal adiposity loss after 12 weeks and produced lower insulin and IL-6 levels after 6 weeks and 12 weeks. These results support the study hypothesis by showing that this type of intervention can significantly improve MetS risk factors.

Although the women did not meet the criteria for MetS, they were overweight (BMI =28 kg/m2) at baseline, and following the intervention a reduction in fat mass of 2.6 kg (0.12 kg abdominal adiposity) and WC (3.7 cm) was observed. These results support our previous laboratory findings involving 15 weeks of HIIE where a 2.5 kg reduction in fat mass (0.15 kg in abdominal adiposity) was found.Citation9 Therefore, a shorter intervention in individuals with greater disease risk offered similar benefits. An 8-week study involving older T2DM males found no change in body mass. However, abdominal adiposity was decreased by 44%,Citation28 and longer-duration HIIE (16 weeks) has provided body composition improvements in middle-aged obese women meeting the IDF definition of MetS.Citation7 The mechanism(s) underlying the HIIE fat reduction effect is undetermined at this time. However, visceral fat exhibits higher catecholamine-induced lipolysis through increased expression of catecholamine receptors.Citation29 Prior research in our laboratory noted that catecholamine levels increased significantly after a bout of HIIE.Citation30 Collectively, these results indicate that HIIE protocols conducted for 12 weeks and longer result in significant decreases in fat mass and abdominal adiposity, reducing the risk of obesity and MetS.

Although the effect of HIIE on muscle mass has not been extensively examined, studies using DEXA have found that leg and trunk muscle mass were significantly increased in females by 0.6 kg and by 1.2 kg in males after 15 weeks and 12 weeks of HIIE.Citation9,Citation20 The 0.6 kg increase in leg and trunk muscle mass found after HIIE in the present study confirms the ability of this type of exercise to increase muscle mass. This effect may be important for fat loss programs, as muscle mass is typically decreased after dietary restrictionCitation31 and is typically unchanged after aerobic exercise training.Citation32

In 2011, Esposito et alCitation33 found improvements in body composition in overweight and obese men, some of whom met the criteria for MetS following long-term consumption (with or without caloric restriction) of a Mediet. The benefits found in the current study of young sedentary but otherwise healthy women represent the combined benefits of HIIE and a Mediet. One possible mechanism may be due to the fact that the triglyceride levels were significantly lower following FEM compared with CON, which was most likely due to the Mediet because triglyceride improvements were not found in a prior interval sprinting training study.Citation9 Total kilojoules (13%), fat (5%), saturated fat (3%), and cholesterol intake (27%) decreased in the FEM group compared with the CON group (). These results have been previously demonstrated following a 2-year Mediet (calorie reduction) and physical activity intervention in an obese population of premenopausal healthy women.Citation34 The average two-point increase in MDS throughout the literature is considered substantial, as an increase of MDS as little as one point was found to significantly reduce mortality rates in populations by one-fifth.Citation35 More specifically, fiber (25%) and fruit and nut (41%) consumption significantly increased, while a significant decrease (39%) in meat, poultry, and egg was found. These dietary improvements are believed to contribute to a significant increase (22%) in the MDS score, representing adherence to the Mediet, which was associated with an improved fat mass and MetS variables seen previously,Citation11 along with a reduction in diabetes risk.Citation36 The system incorporated in the FEM investigation (MDS medians used) may have strengthened the association, as no relation to BMI in either men or women was found in a large Greek epidemiological study.Citation22 Specific alterations within the dietary components of Mediet (less meat, poultry, and egg and greater legume intake) favorably impacted metabolic variables, lipids, and body composition following the 12-week intervention. Therefore, the combination of a Mediet (verified through an MDS) and HIIE offered additional benefits that the HIIE alone could not offer in relation to body composition and fasting whole blood triglyceride levels.

Fasting insulin decreased significantly by 32% ( and ) following the intervention and was similar to the reduction (31%) demonstrated by Trapp et al.Citation9 This dramatic reduction in IR appears to be a feature of HIIE, and in healthy, nondiabetic individuals the improvement in fasting insulin and IR ranged from 23% to 33%,Citation9,Citation10 whereas in individuals possessing T2DM two studies have reported greater insulin sensitivity improvements of 46% and 58%.Citation28,Citation37 The increase in insulin sensitivity may be the result of alterations in the skeletal muscleCitation38 signaling pathways and glucose metabolism enhancing sensitivity to insulin, the lower inflammatory markers, or changes to adipocytokines and hormones.Citation39,Citation40 Increased insulin sensitivity has also been shown with the consumption of the Mediet.Citation36 As previously mentioned, the increase in fiber and nut consumption along with an increase in the MDS may have contributed to the metabolic improvements currently found that were slightly better than with HIIE alone in women.Citation9

The anti-inflammatory response (33% reduction in IL-6, ) after 6 weeks and 12 weeks in the FEM group is similar to the results of a study performed in T2DM, obese, and lean men for 12 weeks involving 60 minutes of exercise daily with a 55%, 17%, and 32% reduction in IL-6.Citation41 Similarly, studies assessing the short-term consumption of the Mediet have shown reductions in low-grade systemic inflammation,Citation42 which may be due to an increase in antioxidant consumption, an anti-inflammatory effect related to training, or improvements in other metabolic factors associated with low-grade systemic inflammation.Citation42–Citation44

Cardiorespiratory fitness levels increased significantly by 15% in the intervention group and the CON women showed no change (). Similar HIIE protocols (same laboratory, varying duration) resulted in a 15%–24% increase in VO2peak.Citation9,Citation20 More intense HIIE programs (12–24 weeks) have noted large increases in VO2max Citation37,Citation45,Citation46 of 41% in T2DMCitation37 and older cardiac rehabilitation patients.Citation46 The effect of HIIE on cardiorespiratory fitness is impressive, given that the most intense component of HIIE is anaerobic exercise, and possible mechanisms may involve enhanced cardiac contractility,Citation45 increased skeletal muscle buffering capacity, increased mitochondrial biogenesis, and oxidative capacity.Citation47 Also, repeated bouts of HIIE have been shown to result in a progressive increase in adenosine triphosphate generation, so that by halfway through a bout of intense HIIE, the majority of adenosine triphosphate was generated oxidatively.Citation48 Significant oxidative adaptations in the exercising muscle underlie the significant increases in maximal oxygen uptake documented previously after regular HIIE.Citation49

The calculated MetS score based on the IDF definition for MetSCitation3 decreased for the FEM women and increased for the CON women, although not significantly. Despite no significant reductions in the calculated MetS score within the FEM women, the improvements found in body composition, inflammation, and cardiorespiratory fitness are related to a lower risk for disease.Citation7,Citation11

A limitation of this study may involve postintervention testing and menstrual cycle. All post-testing sessions were conducted in the days immediately following, with a minimum of 24 hours between the last session and the first post-test. Due to variations in the menstrual cycle between participants, not all women were measured during the same phase of the menstrual cycle (pre and post), and some variability in water weight gain with cycle phase should be considered.

Following a 12-week multicomponent intervention, significant reductions in body composition, IR, inflammation, and triglyceride levels were found. The greatest decrease in insulin, HOMA-IR, and IL-6 had occurred by week 6 of the intervention. Therefore, an intervention trial incorporating HIIE, Mediet, and ω-3 consumption improved a number of MetS criteria in young premenopausal overweight women.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants who donated their time to the study; Dr Joachim Fleuher at YourHealth, Manly, Australia, for the donation of the ω-3 supplements; Christian Kennel for creating the LifeSprint exercise music; and Darren Irvine and Jennifer Mann for help with data collection.

Disclosure

All authors declare no conflicts of interest in any company or organization sponsoring the research currently or at the time the research was done. No funding was received for this work.

References

- Eckel RH Grundy SM Zimmet PZ The metabolic syndrome Lancet 2005 365 9468 1415 1428 15836891

- Beltran-Sanchez H Harhay MO Harhay MM McElligott S Prevalence and trends of metabolic syndrome in the adult US population, 1999–2010 J Am Coll Cardiol 2013 62 8 697 703 23810877

- Alberti KG Zimmet P Shaw J Metabolic syndrome – a new worldwide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes Federation Diabet Med 2006 23 5 469 480 16681555

- Colca JR Insulin sensitizers may prevent metabolic inflammation Biochem Pharmacol 2006 14 72 2 125 131 16472781

- Dvorak RV DeNino WF Ades PA Poehlman ET Phenotypic characteristics associated with insulin resistance in metabolically obese but normal-weight young women Diabetes 1999 48 11 2210 2214 10535456

- Inelmen EM Toffanello ED Enzi G Predictors of drop-out in overweight and obese outpatients Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 29 1 122 128 15545976

- Irving BA Davis CK Brock DW Effect of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008 40 11 1863 1872 18845966

- Tjonna AE Lee SJ Rognmo O Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome: a pilot study Circulation 2008 118 4 346 354 18606913

- Trapp EG Chisholm DJ Freund J Boutcher SH The effects of high-intensity intermittent exercise training on fat loss and fasting insulin levels of young women Int J Obes (Lond) 2008 32 4 684 691 18197184

- Tjonna AE Stolen TO Bye A Aerobic interval training reduces cardiovascular risk factors more than a multitreatment approach in overweight adolescents Clin Sci (Lond) 2009 116 4 317 326 18673303

- Esposito K Kastorini CM Panagiotakos DB Giugliano D Mediterranean diet and metabolic syndrome: an updated systematic review Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2013 14 3 255 263 23982678

- Di Daniele N Petramala L Di Renzo L Body composition changes and cardiometabolic benefits of a balanced Italian Mediterranean diet in obese patients with metabolic syndrome Acta Diabetol 2013 50 3 409 416 23188216

- Esposito K Marfella R Ciotola M Effect of a Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial JAMA 2004 292 12 1440 1446 15383514

- Carpentier YA Portois L Malaisse WJ n-3 fatty acids and the metabolic syndrome Am J Clin Nutr 2006 83 Suppl 6 1499S 1504S 16841860

- Engler MM Engler MB Omega-3 fatty acids: role in cardiovascular health and disease J Cardiovasc Nurs 2006 21 1 17 24 16407732

- Harris WS n-3 fatty acids and serum lipoproteins: human studies Am J Clin Nutr 1997 65 Suppl 5 1645S 1654S 9129504

- Hill AM Buckley JD Murphy KJ Howe PR Combining fish-oil supplements with regular aerobic exercise improves body composition and cardiovascular disease risk factors Am J Clin Nutr 2007 85 5 1267 1274 17490962

- Kesse-Guyot E Ahluwalia N Lassale C Hercberg S Fezeu L Lairon D Adherence to Mediterranean diet reduces the risk of metabolic syndrome: a 6-year prospective study Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2013 23 7 677 683 22633793

- Landaeta-Diaz L Fernandez JM Da Silva-Grigoletto M Mediterranean diet, moderate-to-high intensity training, and health-related quality of life in adults with metabolic syndrome Eur J Prev Cardiol 2013 20 4 555 564 22496276

- Heydari M Freund J Boutcher SH The effect of high-intensity intermittent exercise on body composition of overweight young males J Obes 2012 2012 480467 22720138

- Day JR Rossiter HB Coats EM Skasick A Whipp BJ The maximally attainable VO2 during exercise in humans: the peak vs. maximum issue J Appl Physiol 2003 95 5 1901 1907 12857763

- Trichopoulou A Naska A Orfanos P Trichopoulos D Mediterranean diet in relation to body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio: the Greek European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study Am J Clin Nutr 2005 82 5 935 940 16280422

- Carey DG Jenkins AB Campbell LV Freund J Chisholm DJ Abdominal fat and insulin resistance in normal and overweight women: direct measurements reveal a strong relationship in subjects at both low and high risk of NIDDM Diabetes 1996 45 5 633 638 8621015

- Norton K Olds T Anthropometrica: A Textbook of Body Measurement for Sports and Health Courses Sydney, Australia UNSW Press 1996

- Borg G Psychological aspects of physical activities Larson LA Fitness, Health and Work Capacity New York, USA MacMillan 1974 141 163

- Alberti G Zimmet P Shaw J Grundy S The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome Brussels, Belgium International Diabetes Foundation 2006 Available from: http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/MetS_def_update2006.pdf Accessed August 7, 2014

- Eklund CM Proinflammatory cytokines in CRP baseline regulation Adv Clin Chem 2009 48 111 136 19803417

- Boudou P Sobngwi E Mauvais-Jarvis F Vexiau P Gautier JF Absence of exercise-induced variations in adiponectin levels despite decreased abdominal adiposity and improved insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic men Eur J Endocrinol 2003 149 5 421 424 14585088

- Ostman J Arner P Engfeldt P Kager L Regional differences in the control of lipolysis in human adipose tissue Metabolism 1979 28 12 1198 1205 229383

- Trapp EG Chisholm DJ Boutcher SH Metabolic response of trained and untrained women during high-intensity intermittent cycle exercise Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007 293 6 R2370 R2375 17898114

- Saris W The role of exercise in the dietary-treatment of obesity Int J Obes 1993 17 S17 S21

- Stiegler P Cunliffe A The role of diet and exercise for the maintenance of fat-free mass and resting metabolic rate during weight loss Sports Med 2006 36 3 239 262 16526835

- Esposito K Di Palo C Maiorino MI Long-term effect of Mediterranean-style diet and calorie restriction on biomarkers of longevity and oxidative stress in overweight men Cardiol Res Pract 2011 2011 293916 21197397

- Esposito K Pontillo A Di Palo C Effect of weight loss and lifestyle changes on vascular inflammatory markers in obese women: a randomized trial JAMA 2003 289 14 1799 1804 12684358

- Osler M Schroll M Diet and mortality in a cohort of elderly people in a north European community Int J Epidemiol 1997 26 1 155 159 9126515

- Georgoulis M Kontogianni MD Yiannakouris N Mediterranean diet and diabetes: prevention and treatment Nutrients 2014 6 4 1406 1423 24714352

- Mourier A Gautier JF De Kerviler E Mobilization of visceral adipose tissue related to the improvement in insulin sensitivity in response to physical training in NIDDM. Effects of branched-chain amino acid supplements Diabetes Care 1997 20 3 385 391 9051392

- Richards JC Johnson TK Kuzma JN Short-term sprint interval training increases insulin sensitivity in healthy adults but does not affect the thermogenic response to beta-adrenergic stimulation J Physiol 2010 588 15 2961 2972 20547683

- Abete I Parra D Crujeiras AB Goyenechea E Martinez JA Specific insulin sensitivity and leptin responses to a nutritional treatment of obesity via a combination of energy restriction and fatty fish intake J Hum Nutr Diet 2008 21 6 591 600 18759956

- Balagopal P George D Yarandi H Funanage V Bayne E Reversal of obesity-related hypoadiponectinemia by lifestyle intervention: a controlled, randomized study in obese adolescents J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005 90 11 6192 6197 16131584

- Dekker MJ Lee S Hudson R An exercise intervention without weight loss decreases circulating interleukin-6 in lean and obese men with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus Metabolism 2007 56 3 332 338 17292721

- Estruch R Anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet: the experience of the PREDIMED study Proc Nutr Soc 2010 69 3 333 340 20515519

- Richard C Couture P Desroches S Lamarche B Effect of the Mediterranean diet with and without weight loss on markers of inflammation in men with metabolic syndrome Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013 21 1 51 57 23505168

- Mitjavila MT Fandos M Salas-Salvado J The Mediterranean diet improves the systemic lipid and DNA oxidative damage in metabolic syndrome individuals. A randomized, controlled, trial Clin Nutr 2013 32 2 172 178 22999065

- Helgerud J Hoydal K Wang E Aerobic high-intensity intervals improve VO2max more than moderate training Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007 39 4 665 671 17414804

- Wisloff U Stoylen A Loennechen JP Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study Circulation 2007 115 24 3086 3094 17548726

- Gibala MJ McGee SL Metabolic adaptations to short-term high-intensity interval training: a little pain for a lot of gain? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2008 36 2 58 63 18362686

- Putman CT Jones NL Lands LC Bragg TM Hollidge-Horvat MG Heigenhauser GJ Skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase activity during maximal exercise in humans Am J Physiol 1995 269 3 Pt 1 E458 E468 7573423

- Harmer AR Chisholm DJ McKenna MJ Sprint training increases muscle oxidative metabolism during high-intensity exercise in patients with type 1 diabetes Diabetes Care 2008 31 11 2097 2102 18716051