Dear editor

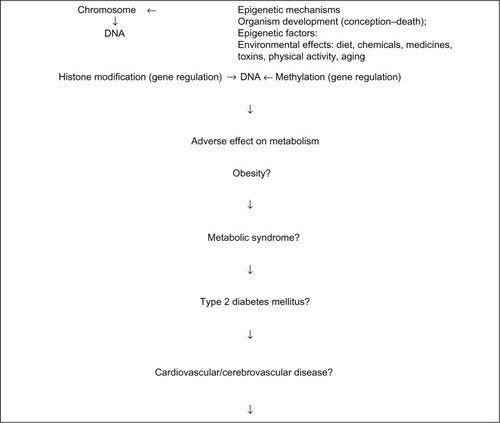

Epigenetics can be defined as the study of heritable changes that affect gene function without modification of the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence.Citation1 The transfer of epigenetic marks through generations is not well understood, and their transmission is in dispute.Citation2 Epigenetic marks are tissue-specific and include DNA methylation and histone modifications that mediate biological processes, such as imprinting (). Many imprinted genes are regulators of gene expression controlling growth. Imprinting disorders often feature obesity as one of their characteristics.Citation3

Figure 1 Epigenetic mechanisms.

Abbreviation: DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid.

Genomic imprinting determines expression of alleles, creating an equilibrium between the expression of the parental alleles influencing growth and metabolism.Citation4

The identification of susceptible loci, and finding the causal genes and variants in each locus for obesity may allow molecular and physiological investigations. However, the knowledge of the mechanisms through which these contribute to susceptibility to obesity will not necessarily provide the requisite management strategies.

Geneticists have long since identified the obesity gene (FTO)Citation5 and a low-fat gene (APOA5),Citation6 and that variations in the adiponectin gene (single nucleotide polymorphism [SNP] 276 G allele) can lead to hypoadiponectinemia, which then results in insulin resistance, the metabolic syndrome, increased atherosclerosis, morbidity, and ultimately, premature mortality.Citation7 Using exome sequencing, a low-frequency coding variant has been identified in the SYPL2 gene associated with morbid obesity.Citation8 This gene may be involved in the development of excess body fat.

Hypokinesis, in conjunction with excess caloric intake over expenditure, leads to obesity, which can then result in the metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease (CVD), coronary heart disease, and cerebrovascular accident, or “stroke”.Citation9–Citation12

Obesity is also believed to predispose to certain types of cancer,Citation13 such as breastCitation14 and colon cancer.Citation15

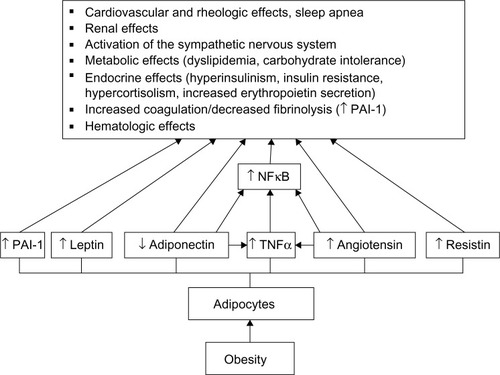

However, the assertion that the complete absence of fat cells (adipocytes) is metabolically advantageous is a fallacy. Adipocytes play an important role in health by their hormonal role in the regulation of energy intake and fat storage, and function as an endocrine gland ().Citation16,Citation17 Adipocytes secrete approximately 50 adipokines with diverse functional roles.Citation18

Figure 2 The endocrine function of an adipocyte.

The average human phenotype contains 30 billion fat cells, weighing approximately 13.5 kg.Citation19 To establish the dynamics within the stable population of adipocytes in adults, adipocyte turnover can be measured by analyzing the integration of 14C derived from nuclear bomb tests in genomic DNA. If excess weight is gained as an adult, fat cells increase approximately fourfold in size before dividing and increasing the absolute number of fat cells present. However, even after marked weight loss, the number of fat cells stays constant in adulthood in lean and obese individuals, indicating that the number of adipocytes is set during childhood and adolescence.Citation19 Approximately 10% of fat cells die and are replaced annually. The expansion of the fat cell population and the final number of adipocytes in the adult body appears to occur at an earlier age in obese people. Fatter people experience a period of rapid adipoctye production around the age of 2 years and reach their adult number of fat cells when they are approximately 16.5 years old.Citation19 Lean people, however, recruit fat cells most rapidly at approximately 6 years old, with their fat cell population reaching its adult size at approximately 18.5 years. Obese people have as many as twice the number of adipocytes as lean people.Citation19

Scientific evidence supports the concept that gene expression in our physically active ancestors reduced adverse physiological effects that may occur with a sedentary lifestyle. To prevent the development of these adverse physiological effects, children who experience appropriate nutrition and regular exercise during their growing years display healthy patterns of physical maturation consistent with their genetic potential.Citation20 However, a genetic explanation cannot explain how humans have become so fat over such a short time frame.Citation21 Heredity can only explain 67% of the population variance in obesity.Citation22

Genetics are unlikely to account fully for the prevalence of obesity – it must be due to the declining rates of physical activity and an increase in the consumption of energy-dense foods.Citation23,Citation24

The differences in phenotypes and physiology between two geographically separate but genetically similar Pima Indian tribes suggests the importance of the environmental effect, especially physical activity, on the genome.Citation25 The Mexican Pima Indians were found to expend 2,100–2,520 kJ day−1 more in physical activity than did their obese Arizonian Pima equivalents, to have had a diet lower in fat and higher in fiber content, and to weigh 26 kg less.Citation25 As a consequence, the Mexican Pima Indians did not have the diabetes prevalence of the Arizonian Pima Indians.Citation26

Children of pregnant women exposed to the Dutch famine of 1944 were more susceptible to diabetes, obesity, CVD, renal disease, and other health problems.Citation27 The children of the women who were pregnant during the famine were smaller, and when these children grew up and had children, those children were also smaller than average.Citation28 This suggested that the famine experienced by the mothers caused epigenetic changes that were passed down to the next generation.

Genetic predisposition is the primary cause of most of the rare diseases that affect one in 17 people.Citation29,Citation30 Every human possesses approximately three million sequence variants of which approximately 400 can predispose to pathology, in adverse environmental circumstances.Citation31

Could lifestyle assessments and avoidance of potential risks have beneficial effects on a person’s health despite genetic variants? This question can only truly be answered if we are able to sequence individual genomes on demand and then, only if it is cost effective.

The general public should be concerned with prevention rather than the management of obesity and its sequelae. Despite considerable financial investment, the pharmaceutical industry has provided only palliation of obesity rather than cure.

Physical activity should be the main agenda of the Department of Health and the responsibilities for its effective prescription and assessments placed in the hands of appropriate health professionals. More consideration should be given to effective exercise prescription rather than the premature introduction of prescription medicines, such as the latest insulin analog or glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist (GLP-1 agonist), to type 2 diabetics, which appears to be only palliating the disease state and elevating the public purse’s annual budget.Citation32

In the UK in 1998 the anti-obesity drugs’ bill was £20,000.00 and in 2005 it was £38 million, with increased prescribing of drugs such as orlistat and sibutramine.Citation33 In 2010 it was £50 million.Citation34

The annual drugs bill in the UK is currently around £12 billion, which equates to just approximately 10% of National Health Service (NHS) expenditure, having risen around 3.5% a year between 2007 and 2013.

When the NHS was launched in 1948 it had a budget of £437 million (circa £9 billion at today’s value). For 2015 it is predicted to be £115.4 billion.Citation35

The obesity epidemic that we are experiencing is a global phenomenon. In 2005 more than 1.6 billion adults over the age of 15 years, were overweight and 400 million were obese. By 2015 it has been predicted that more than 2.3 billion adults over the age of 15 years, will be overweight and at least 700 million will be obese.Citation36 With global projections, more than 2.16 billion will be overweight and 1.12 billion will be obese individuals by 2030.Citation36

Watson and Crick discovered the structure of DNA in 1953,Citation37 and Sanger identified the amino acid sequence of insulin in 1955, and nucleic acid sequencing becoming a major target of early molecular scientists.Citation38

However, we are no nearer to eradicating the most basic of diseases, associated with obesity.

Have we really had a single or series of genetic mutations to account for a 21.4% and a 24% increase in obesity in males and females respectively, in a mere third of a century?

Sequencing the first human genome took 13 years and was completed in 1986 at a cost of £2 billion.Citation39 Today we can sequence a complete human genome in two days at a cost of approximately £4,000.00.Citation39

Bulk sequencing all 20–25,000 human protein coding genes, the exome, now costs less than £500.Citation29

Targeting the screening of a specific panel of genes known to be associated with a particular phenotype, as opposed to screening mutations, would appear necessary in the belief that eating five pieces of fruit and vegetables a day will keep us slim, healthy, and disease free.Citation40 Scientists are required to identify variants in genes, known to be pathogenic in an effort to decide on preventative, curative or palliative action.

The investment continues as the government’s decision to gene sequence 100,000 whole genomes at a cost to the public purse of £100 million hoping to identify the reason for the current obesity pandemic, pursuant to the work of the Wellcome Trust’s Sanger Institute initiating the Human Genome Project.Citation29,Citation41 However, will such an investment stimulate the general population to cease eating refined processed foods and commence exercising?

The fact there is so much money available for such a resource is surprising. Should not that money be available to employ more exercise scientists, who can advise these obese phenotypes that eating the correct diet and performing even limited amounts of exercise can bring about positive transgenerational epigenetic changes to the major CVD risk factors.Citation42,Citation43

Currently the vast sums of money spent in researching pharmacotherapy alone appear to be having very little effect. A greater investment should be applied to promoting exercise in conjunction with exome sequencing and epigenetic research.

Human growth hormone (hGH) which controls the body’s ability to metabolize carbohydrate, fat, and protein and deposit any excess fat in the appropriate site, commences a downward spiral, after full adult growth has been attained.Citation44 It decreases by 14% per decade from the age of 20 years.Citation44 Exercising for more than 10–20 minutes at an oxygen uptake (VO2max) of 70%, stimulates pituitary release of hGH by five- to tenfold.Citation45 Protein consumption stimulates pituitary release of hGH.Citation46 Carbohydrate and fat ingestion inhibit pituitary release of hGH.Citation47 Also obesity causes a blunted response to hGH compounding the adverse situation.Citation48

Physical activity can ultimately prevent many problems associated with obesity.Citation43 There is a lower cancer incidence rates among the adult Amish population, compared with non-Amish population, due to increased physical activity.Citation49 Physical activity differences can be identified in childhood in the Amish compared with non-Amish population and accounts for Amish children being approximately 3.3 times less likely to be overweight compared to non-Amish children.Citation50 The average American would aspire to walk approximately 10,000 steps per day to maintain a healthy body mass. In one study the average number of steps walked per day was 18,425 for Amish men versus 14,196 for Amish women, who have a very low incidence of obesity. The Old Order Amish refrain from driving cars, using electrical appliances, and employing other modern conveniences. Labor-intensive farming is still the preferred occupation.Citation51

Conclusion

Obesity is a consequence of a high saturated fat, a refined carbohydrate diet, and an increased input over expenditure, combined with reduced exercise. Proactive research scientists are working to identify explanations, at the molecular level, relating exercise to health improving epigenetic changes.

Prevention must always be better than cure. When a large segment of the population adopts modest improvements in health behaviors, the overall disease burden in the population is likely to be reduced more dramatically than if a modest segment of the population adopts large changes.Citation52

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this communication.

References

- BirdAPerceptions of epigeneticsNature20074477143396 39817522671

- ChongSYoungsonNAWhitelawEHeritable germline epimutation is not the same as transgenerational epigenetic inheritanceNat Genet2007395574 575 author reply 57517460682

- HerreraBMKeildsonSLindgrenCMGenetics and epigenetics of obesityMaturitas201169141 4921466928

- SmithFMGarfieldASWardARegulation of growth and metabolism by imprinted genesCytogenet Genome Res20061131–4279 29116575191

- FraylingTMTimpsonNJWeedonMNA common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesityScience20073165826889 89417434869

- CorellaDLaiCQDemissieSAPOA5 gene variation modulates the effects of dietary fat intake on body mass index and obesity risk in the Framingham Heart StudyJ Mol Med (Berl)2007852119 12817211608

- González-SánchezJLZabenaCAMartínez-LarradMTAn SNP in the adiponectin gene is associated with decreased serum adiponectin levels and risk for impaired glucose toleranceObes Res2005135807 81215919831

- JiaoHArnerPGerdhemPExome sequencing followed by genotyping suggests SYPL2 as a susceptibility gene for morbid obesityEur J Hum Genet Epub201411 19

- RathmannWGianiGGlobal prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030Diabetes Care200427102568 2569 author reply 256915451946

- LiZBowermanSHeberDHealth ramifications of the obesity epidemicSurg Clin North Am2005854681 701 v16061080

- Van GaalLFMertensILDe BlockCEMechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular diseaseNature20064447121875 88017167476

- KahnHSObesity and risk of myocardial infarction: the INTERHEART studyLancet200636795161053 105416581396

- AndersonASCaswellSObesity management – an opportunity for cancer preventionSurgeon200975282 28519848061

- MorimotoLMWhiteEChenZObesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative (United States)Cancer Causes Control2002138741 75112420953

- LarssonSCWolkAObesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studiesAm J Clin Nutr2007863556 56517823417

- FraynKNKarpeFFieldingBAMacdonaldIACoppackSWIntegrative physiology of human adipose tissueInt J Obes2003278875 888

- LiYFrommeTSchweizerSSchöttlTKlingensporMTaking control over intracellular fatty acid levels is essential for the analysis of thermogenic function in cultured primary brown and brite/beige adipocytesEMBO Rep201415101069 107625135951

- GreenbergASObinMSObesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolismAm J Clin Nutr2006832461S 465S16470013

- SpaldingKLArnerEWestermarkPODynamics of fat cell turnover in humansNature20084537196783 78718454136

- BoothFWChakravarthyMVSpangenburgEEExercise and gene expression: physiological regulation of the human genome through physical activityJ Physiol2002543Pt 2399 41112205177

- ToyeAADumasMEBlancherCSubtle metabolic and liver gene transcriptional changes underlie diet-induced fatty liver susceptibility in insulin-resistant miceDiabetologia20075091867 187917618414

- MaesHHNealeMCEavesLJGenetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposityBehav Genet1997274325 3519519560

- BrownsonRCBoehmerTKLukeDADeclining rates of physical activity in the United States: what are the contributors?Annu Rev Public Health200526421 44315760296

- LedikweJHBlanckHMKettel KhanLDietary energy density is associated with energy intake and weight status in US adultsAm J Clin Nutr20068361362 136816762948

- EsparzaJFoxCHarperITDaily energy expenditure in Mexican and USA Pima indians: low physical activity as a possible cause of obesityInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord200024155 5910702751

- PratleyREGene-environment interactions in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus: lessons learned from the Pima IndiansProc Nutr Soc1998572175 1819656318

- RoseboomTde RooijSPainterRThe Dutch famine and its long-term consequences for adult healthEarly Hum Dev2006828485 49116876341

- PainterRCOsmondCGluckmanPHansonMPhillipsDIRoseboomTJTransgenerational effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on neonatal adiposity and health in later lifeBJOG2008115101243 124918715409

- BurnJShould we sequence everyone’s genome? YesBMJ2013346f313323694691

- Department of HealthThe 2009 Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer The 2009 Annual Report of the Chief Medical OfficerLondonDepartment of Health2010

- XueYChenYAyubQ1000 Genomes Project ConsortiumDeleterious- and disease-allele prevalence in healthy individuals: insights from current predictions, mutation databases, and population-scale resequencingAm J Hum Genet20129161022 103223217326

- ScholzGHFleischmannHBasal insulin combined incretin mimetic therapy with glucagon-like protein 1 receptor agonists as an upcoming option in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a practical guide to decision makingTher Adv Endocrinol Metab20145595 12325419451

- PadwalRLiSKLauDCLong-term pharmacotherapy for obesity and overweightCochrane Database Syst Rev20043CD00409415266516

- Dramatic rise in slimming drugs prescriptions leaves NHS with £50 m billThe Daily Mail20109 20 Available from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-1313362/Slimming-drugs-cost-NHS-50m.htmlAccessed January 3, 2015

- nhs.uk [homepage on the Internet]The NHS in England: About the National Health Service (NHS)National Health Service2015 [updated January 7, 2015; cited January 3, 2015]. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/thenhs/about/Pages/overview.aspxAccessed February 11, 2015

- FontvieilleAMRavussinEMetabolic rate and body composition of Pima Indian and Caucasian childrenCrit Rev Food Sci Nutr1993334–5363 3688357498

- WatsonJDCrickFHA structure for deoxyribose nucleic acidNature19531714356737 73813054692

- StrettonAOWThe first sequence. Fred Sanger and insulinGenetics20021622527 53212399368

- FlinterFShould we sequence everyone’s genome? NoBMJ2013346f313223694690

- KeysAAndersonJTAresuMPhysical activity and the diet in populations differing in serum cholesterolJ Clin Invest195635101173 118113367213

- WrightCFMiddletonABurtonHPolicy challenges of clinical genome sequencingBMJ2013347f684524270507

- BuchanDSYoungJDBoddyLMBakerJSIndependent associations between cardiorespiratory fitness, waist circumference, BMI, and clustered cardiometabolic risk in adolescentsAm J Hum Biol201426129 3524136895

- DenhamJMarquesFZO’BrienBJCharcharFJExercise: putting action into our epigenomeSports Med2014442189 20924163284

- IranmaneshALizarraldeGVeldhuisJDAge and relative adiposity are specific negative determinants of the frequency and amplitude of growth hormone (GH) secretory bursts and the half-life of endogenous GH in healthy menJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19917351081 10881939523

- FelsingNEBraselJACooperDMEffect of low and high intensity exercise on circulating growth hormone in menJ Clin Endocrinol Metab1992751157 1621619005

- RootAWRootMJClinical pharmacology of human growth hormone and its secretagoguesCurr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord20022127 5212477295

- MasudaAShibasakiTNakaharaMThe effect of glucose on growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone-mediated GH secretion in manJ Clin Endocrinol Metab1985603523 5263919046

- ScacchiMPincelliAICavagniniFGrowth hormone in obesityInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord1999233260 27110193871

- KatzMLFerketichAKBroder-OldachBPhysical activity among Amish and non-Amish adults living in Ohio AppalachiaJ Community Health2012372434 44021858689

- HairstonKGDucharmeJLTreuthMSComparison of BMI and physical activity between old order Amish children and non-Amish childrenDiabetes Care2013364873 87823093661

- BassettDRSchneiderPLHuntingtonGEPhysical activity in an Old Order Amish communityMed Sci Sports Exerc200436179 8514707772

- RoseGEnvironmental factors and disease: the man made environmentBr Med J (Clin Res Ed)19872946577963 965