Abstract

This review provides an outlook of orthostatic tremor (OT), a rare adult-onset tremor characterized by subjective unsteadiness during standing that is relieved by sitting or walking. Recent case series with a long-time follow-up have shown that the disease is slowly progressive, spatially spreads to the upper limbs, and other neurological disorders may develop in about one-third of the patients. The diagnosis of OT hinges on the typical history of unsteadiness during standing, which is confirmed by electromyographic findings of a 13–18 Hz tremor that is typically absent during tonic activation while the patient is sitting and lying. Although the tremor is generated by a central oscillator, cerebellar and/or basal ganglia dysfunction are needed for its manifestation (double lesion hypothesis). However, functional neuroimaging findings have not consistently implicated the dopaminergic system in its pathogenesis. Drug treatments have been largely disappointing with no sustained benefits, although thalamic deep brain stimulation has helped some patients. Large-scale follow-up studies, more drug trials, and novel therapies are urgently needed.

Introduction

Orthostatic tremor (OT) is a rare form of tremor and is characterized by subjective unsteadiness during standing, which is relieved by sitting or walking. Although Pazzaglia et alCitation1 reported it first, it was HeilmanCitation2 in 1984 who brought the entity to limelight when he described the quivering movements of the legs and trunk during standing, often accompanied by a curious sensation of unsteadiness that was relieved by walking or leaning against an object often described as a tremor of the lower limbs and the trunk, extant evidence however shows that this tremor could involve other parts of the body, especially the upper extremities when they are used to maintain body weight or when they contract isometrically.Citation3 The term Primary Orthostatic Tremor (POT) or idiopathic OT is used when the tremor (whether or not there is upper limb involvement) is not accompanied by additional neurological features.Citation4 Recently, Ganos et alCitation5 have used the term “isolated OT” as a nomenclature for POT; with or without upper extremities involvement. The term orthostatic tremor plus (“OT Plus”) is used when OT is accompanied by other neurological symptoms or conditions.Citation4 The term “Shaky Leg Syndrome” has been suggested by some other authors based on the fact that the tremor is not exclusively orthostatic and that it can also be induced by strong tonic contraction of the leg muscles. The latter terminology fails to reflect the possible involvement of other regions of the body such as the trunk or the upper extremities.Citation6,Citation7 The findings of Boroojerdi et alCitation8 show that while OT is invariably present during stance or other weight-bearing positions, it is, however, not always associated with orthostasis. The term “Orthostasis-independent action tremor” has been suggested for this group of patients.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Classically, the clinical presentation is that of unsteadiness and fear of falling upon standing that has a latency of some seconds or infrequently a few minutes depending on the severity of the disease.Citation4 The unsteadiness increases in intensity until the patient is forced to take a step or sit down to regain balance. When a patient with OT is examined during attempts to stand still, a fine rippling of the muscles of the legs is found. This rippling may be easier to feel than to seeCitation9,Citation10 and sometimes, the tremor may be auscultated using a stethoscope.Citation9 Typically; the diagnosis is reached when patients satisfy the clinical features as defined by the Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor ().Citation11

Table 1 Consensus statement on orthostatic tremor of the Movement Disorders Society

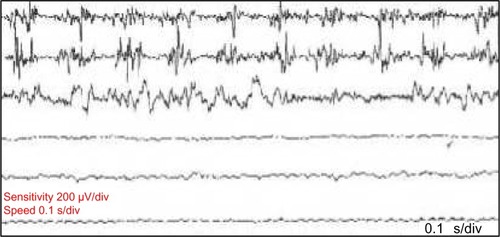

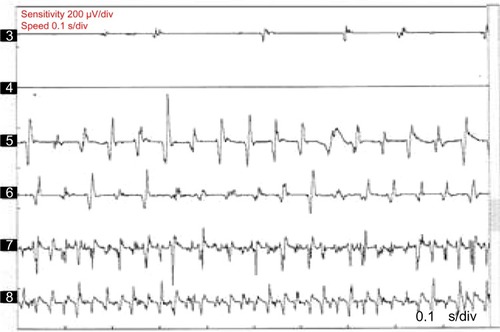

Neurophysiological recording using surface electromyography (EMG) confirms the presence of fast, 13–18 Hz bursts of muscle activities (). Rhythmic activation of upper limbs muscles at the same frequency can be seen if the patient uses the upper limbs to maintain postures such as leaning on a walker or by standing on all fours or when the upper limbs muscles contract isometrically.Citation12 Although high frequency is typical of OT, lower frequency OT characterized by 70–120 ms EMG bursts at frequencies <12 Hz has been recognized.Citation13,Citation14 The occurrence of this low-frequency tremor with orthostasis have occasioned the division of OT into fast OT and slow OT.Citation14,Citation15 Although about a third of patients with OT have underlying disease, it appears that slow OT is often associated with other conditions and may have greater gait involvement and higher likelihood of falls leading to earlier presentation.Citation15 Williams et alCitation16 recently described a patient with cerebellar atrophy and a slow OT (frequency of 9 Hz), while Baker et alCitation17 reported a patient with multiple sclerosis and slow OT (frequency of 4 Hz). Slow OT has also been reported in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD).Citation18 Coffeng et alCitation19 however reported a patient with slow OT (frequency 10–11 Hz) without clinical or imaging evidence of underlying disease, providing proof of the existence of primary slow OT. Although Uncini et alCitation13 had earlier reported a patient with slow OT without underlying disease, the description of the case was so minimal that a secondary origin of the tremor could not be assuredly excluded.Citation19

Figure 1 Polymyographic recordings in a patient with OT.

Abbreviation: OT, orthostatic tremor.

Descriptive demographic and clinical profile of OT patients

Because of its rarity and absence of epidemiological data, incidence and prevalence studies are unknown. Few large case series () are available in the literature; the largest is the recent series of Ganos et al.Citation5 These case series have attempted to profile the demographic characteristics of patients with OT while endeavoring to describe the clinical picture and long-term outcome of the disease.

Table 2 Demography of patients with OT

Demography

The mean age of onset in most studies is in the sixth decade of life while an obvious female preponderance (up to a ratio of four to oneCitation20) is reported by most authors except in the series of Yaltho and OndoCitation21 in which a slight male preponderance was found. When OT Plus syndrome in considered separately, the mean age of onset appears to vary between reports. Gerschlager et alCitation22 found an average age of onset of 61.8, while Yaltho and OndoCitation21 found a younger mean age of onset (55.9 years) in their cohort while Ganos et alCitation5 found an average age of 58.3. This variation notwithstanding, there seems to be a trend toward the older age of onset for OT Plus.

Available studies reveal that most cases are sporadic, and a family history is rare. Among their cohorts of 45 and 68 patients, Yaltho and OndoCitation21 and Ganos et alCitation5 found a positive family history of “Pure OT” in 7% and 1.6%, respectively. A genetic linkage is however suggested by few reports of familial cases such as the reports of OT in monozygotic twinsCitation23 and co-occurrence of OT and ET in two brothers.Citation24 Although a family history of Pure OT is rare, stronger family history of other movement disorders appears to be more common among patients with “OT Plus.” The family history of PD, essential tremor, and other less specified tremor has been documented in first-degree relatives of patients with OT plus. In the series by McManis and Sharbrough,Citation3 24 of the 30 subjects had a family history of movement disorder, and among those, only two had a family member with similar limb tremor even though these relatives were not evaluated by the authors. It is, however, unclear from the study whether the patients had Pure OT or OT Plus.

Clinical profile

In a retrospective review of 41 cases with a clinical diagnosis and electrophysiological diagnosis of OT seen over a 16-year period (1986–2001) at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Gerschlager et alCitation22 profiled the demographic characteristics of their cohort of patients with OT. Of the 41 cases, 28 had been reviewed in the preceding 3 years for a follow-up. Thirty-one (75%) patients were classified as having primary OT. Of these, only seven had leg tremors while the other 24 had accompanying arm tremor. Lack of electrophysiological assessment of the arm tremor in this study limited the ability of the authors to characterize the tremor accurately (the presence of arm tremor among the cohort became apparent during the review). It is unclear whether the postural arm tremor in these OT patients is similar to ET, or whether OT leg tremor in these cases is part of ET, or whether the postural arm tremor is part of OT. Yaltho and OndoCitation21 reported that in a larger case series (n=45), 40/45 (89%) had primary OT with (n=30) or without (n=10) an associated postural arm tremor. In this series, 5/45 (11%) had OT Plus. Of recent, in the largest multicenter cohort of patients with OT,Citation5 a clear female preponderance (76.5%) was demonstrated just like most of the other studies. In this survey, 86.8% of patients presented with isolated OT and 13.2% had additional neurological features. summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics from various studies.

While other neurological disorders can coexist with OT, in some patients, OT may precede other neurological disorders/symptoms, sometimes for as long as 20 years as in the report of dementia with lewy bodies in OT patients by Yaltho and Ondo.Citation21 In the series by Ganos et al,Citation5 seven patients developed new neurological symptoms. One patient developed PD, and five others became slow with gait difficulties, raising the clinical suspicion of PD. However, normal dopamine transporter SPECT scans (DatSCANs) were found in four of them; raising the suspicion that slowness of gait/difficulties could be compensatory to the leg tremor and unsteadiness.Citation5

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological mechanism underlying the development and the manifestation of OT is yet to be fully understood. Available literature has implicated several neuronal circuitry in the cerebellum, brain stem, thalamostriate, and cortico-subcortical pathways.Citation25,Citation26 The cerebello-thalamocortico-spinal loop, in particular, has been implicated.Citation27 It is widely accepted, however, that a central oscillator located in the posterior fossa is responsible for the generation and, probably, the perpetration of OT. The ability to reset OT by electrical stimulation over the posterior fossa further buttresses this theory.Citation28 It has also been suggested that the spinal cord may generate the 16 Hz tremor.Citation29 Spinal cord dorsal column stimulation, typically used for the treatment of medically refractory pain, was beneficial in two patients with OT. Using a stimulation frequency of 50–150 Hz, Krauss et alCitation27 demonstrated both subjective and objective improvement in unsteadiness in patients with OT, suggesting that the spinal cord may be associated with the generation and/or modulation of the tremor. Gerschlager et alCitation22 have proposed a “double lesion” model for the manifestation of OT. According to this model, it is hypothesized that an abnormally active oscillator would have the key role, but OT would only develop if coupled with additional dysfunction at the level of basal ganglia or the cerebellum, resulting in deficient control of the oscillator.

Neurophysiological evaluation of patients has thrown some light on the mechanism of OT generation. In a particular patient, the frequency and timing pattern of the 16 Hz burst of the tremor is the same and fixed, although this fluctuates when such individual assumes a different posture. The high-frequency EMG bursts are time locked and bilateral in arm, leg, truncal, and even facial muscles.Citation26 It has been posited that the abnormally strong peripheral manifestation of the 16 Hz central nervous system oscillation merely unmasks normal central processes rather than a primary pathology of central oscillators the POT. Sharott et alCitation30 postulated that the fast and synchronous tremor might be an exaggeration of physiological postural response under the condition of extreme imbalance since it was shown that a 16 Hz tremor can be recorded in healthy subjects when made extremely unstable either by galvanic vestibular stimulation or by leaning backward.Citation26,Citation30 Objective instability in OT has been confirmed using force platform recordings that demonstrated increased sway path in OT. However, body sway assessment under several conditions has shown a dissociation between objective measurement and subjective feelings of unsteadiness by the patients.Citation31 The authors also suggested that the unsteadiness in OT is caused by a tremulous disruption of proprioceptive afferent activity from the legs causing a cocontraction of the leg muscles to increase stability. The resultant increase in tremor-locked muscles activity further blocks the proprioceptive input, creating a vicious cycle. However, these authors found that the tremor amplitude is independent of objective measures of unsteadiness.Citation31

Although functional neuroimaging studies have yielded inconclusive evidence of nigrostriatal dopaminergic system involvement, reports of early improvement with dopaminergic agents in some OT patients and the association of OT with PD have suggested an involvement of the dopaminergic system. Katzenschlager et alCitation32 have demonstrated a modest bilateral reduction in nigrostriatal dopamine transporter level using 123I-FP-CIT (2-β-carbomethoxy-3-β-(-4-iodophenyl)-N-(3-fluoropropyl)-nortropane) single-photon emission computed tomography in a group of eleven OT patients. In that study, PD was thoroughly screened for (all the patients had normal olfaction on the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test), and no other neurological syndrome was identified, indicating that the mild reduction in nigrostriatal dopaminergic transmission was not due to unidentified PD. In agreement with the previous findings, Spiegel et alCitation33 equally demonstrated an echogenic substantia nigra in six OT patients using transcranial sonography.

In most other functional imaging studies conversely, dopaminergic imaging in patients with Pure OT has largely shown normal nigrostriatal dopamine transporter tracer levels.Citation5,Citation34–Citation37 The absence of appreciable or sustained improvement with dopaminergic agents further supports this observation. Because of this tenuous and rather inconclusive association with the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system, Trocello et alCitation35 have proposed a classification system with separation of high-frequency OT into three different subtypes. Type A corresponds to primary OT without dopaminergic loss; type B consists of OT with mild dopaminergic loss, but no parkinsonian symptoms; and type C consists of OT associated with PD.Citation35 Cerebellar dysfunction (at least subclinically) has also been implicated in the pathophysiology of OT,Citation27,Citation36 and positron emission tomography studies have demonstrated increased blood flow to the cerebellum and the lentiform nuclei in patients with POT.Citation37 Even though florid clinical signs of cerebellar abnormalities are rare, Feil et alCitation38 have documented cerebellar signs such as upper limb dysmetria and intention tremor among a cohort of patients with POT in a recent study on long-term course of OT.Citation38 Albeit, with the history of alcohol consumption in about a third of the cohort, alternative causes of the cerebellar dysfunctions, such as alcoholism, are suspected.

Time course and progression

The absence of a systematic study of the natural history of OT limits the knowledge about its course to available anecdotal reports. The course of OT is often slowly progressive. Although few studies have studied long-time follow-up of patients with OT, the study by Ganos et alCitation5 followed up patients for at least 5 years and found that ∼80% of the cohort reported symptom worsening within the observed timeframe. In the study by Feil et al,Citation38 78% of the patients demonstrated worsening of symptoms. According to Ganos et al,Citation5 patients with clinical worsening had longer disease duration than those without (median 15.5 years vs 10.5 years, respectively). Because the high-frequency tremor that characterizes OT remains unchanged over time (even though amplitude may change), it appears that the observed worsening of body sways over time is not occasioned by the tremor. An alternative hypothesis is that with time, as well as aging, there is a possible alteration of adaptive postural responses with decreased ability to control and minimize center of mass motion.Citation5

Furthermore, some patients may have a spatial spread of the tremor to the trunks and upper extremities as the disease progresses. Although upper limb postural tremor with lower frequency (mimicking ET) may be observed in OTCitation39,Citation40 (), it has been suggested that this slow arm tremor could represent a subharmonic of the leg tremor that has higher frequencies.Citation5 Also, in the course of the disease, patients with OT may proceed to develop other neurological conditions, especially PD and essential tremor. Other neurological disorders that have been documented in patients with OT include dementia with Lewy bodies, ataxic disorders, restless leg syndrome, orofacial dyskinesia, and periodic limb movement in sleep.Citation4,Citation5,Citation21 Patients with OT have been found to have a markedly impaired quality of life as measured by the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).Citation41 Physical functioning, physical role limitations, social functioning, and emotional role limitations were the predominantly impaired domains of quality of life. Among this cohort, depressive symptomatology was also highly prevalent, and it ranges between moderate to severe depression.Citation41

Treatments

Just like the other aspects of this enigmatic illness, there is no large clinical trial to test the efficacy of the commonly used drugs such as clonazepam, gabapentin, primidone, valproate, phenobarbital, levodopa, and pramipexole. Treatment is difficult as the symptoms are often refractory to medication, and in some patients, the initial benefit is followed by loss of efficacy in the long term.Citation4,Citation22

Clonazepam

Clonazepam is usually recommended as first-line drug treatment probably based on the report of Heilman.Citation2 Although it is arguably more beneficial than most other drugs, its side effects may be more. Some authors have recommended the use of gabapentin as the first line.Citation41 Control trial of clonazepam in OT is scarce in the literature.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin, a γ-aminobutyric acid analogue, has been found to be beneficial in patients with OT. Both open-label and cross-over trials have consistently demonstrated the benefit of gabapentin in reducing the tremor amplitude and/or severity, the length of the sway path, and the confidence area of the sway path compared to baseline.Citation42–Citation45

Levodopa and dopamine agonist

In patients with or at risk of parkinsonism, levodopa or dopamine agonist may be helpful.Citation4 In a series by Wills et alCitation46 in which eight patients were treated with levodopa, five patients experienced benefits. One patient had classical OT and developed PD 9 years after its onset. Levodopa improved both parkinsonian symptoms and the high-frequency tremor. Another patient had sustained benefit to levodopa and then developed PD. However, only one patient, out of the eight treated with levodopa,Citation46 had a benefit sustained >24 months.Citation22 An open-label study of levodopa treatment >2 months using 600 mg/d led to some improvement in two of five patients but no significant overall change and no sustained benefit.Citation32 Pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, was effective in a single case report.Citation47 Summarily, dopaminergic agents may be helpful in some patients over a short period of time, particularly those with, or at risk of developing PD.

The trial of levetiracetam in a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study showed a disappointing result.Citation47 Primidone, however, was reported to be beneficial in a patientCitation48 but no available clinical trials yet.

Botulinum toxin

Although it has been suggested that jaw tremor in the frequency of OT may be treated successfully with botox,Citation49 a trial of 200 IU of abobotulinumtoxin A was found to be ineffective in the treatment of OT. Eight patients with electro physiologically confirmed POT were evaluated in this randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Each patient received injections of either 200 mU abobotulinumtoxin A or 0.9% saline in the tibialis anterior bilaterally and then crossed over after 20 weeks. There were no significant differences in the primary outcome measures of time from standing to unsteadiness or symptom diary scores.Citation49

Drug treatment in OT is largely inadequate. Only ∼12% of patients who did not respond to clonazepam and gabapentin would find other medications beneficial.Citation22

Surgical treatment

Surgical intervention has been tried in a few patients with severe, medication-resistant OT.Citation5,Citation22 Bilateral deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the thalamic nucleus ventralis intermedius medialis (Vim) appears to produce sustained clinical improvement.Citation50–Citation52 However, clinical improvement was not sustained in a patient with unilateral thalamic Vim DBS.Citation53 Spinal cord dorsal column stimulation has been beneficial in two patients with OT.Citation27 Thalamic DBS can be complicated by electrode displacement with resultant loss of function and worsening of tremor as in the report by Contarino et al.Citation54

The therapeutic studies that have been undertaken since 1998 are summarized in . In the future, effective therapies are more likely to stem from a better understanding of the fundamental pathophysiology of OT. Larger clinical trials are needed to influence the therapeutic decisions. Although the disease is slowly progressive, development of disease-modifying treatment may be the next quest, especially in view of its association with other neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD.

Table 3 Drug studies in orthostatic tremor

Conclusion

Despite greater awareness in the recent times since its first report, OT still remains enigmatic. Increasing knowledge about its pathophysiology has been assisted by the results of functional neuroimaging and successful therapies such as spinal cord stimulation and thalamic DBS. Because of its rarity, large cohort studies may be a herculean task. The need for such large-scale study is however pressing, if we are to get a better understanding of this disease. Novel therapies are also required in view of the insignificant and inconsistent benefits of the currently available therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Drs Rufus O Akinyemi and Aysegul Gunduz for their helpful comments on the manuscript and also thanks Professor Meral E Kiziltan, who supplied the figures used in this review.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PazzagliaPSabattiniLLugaresiESu di un singolare disturbodeura stazione eretta (osservazione di tri casi) [About a singular disturbance of upright position (observation of three cases)]Riv Freniatr197096450457 Italian

- HeilmanKMOrthostatic tremorArch Neurol19844188808816466163

- McManisPGSharbroughFWOrthostatic tremor: clinical and electrophysiological characteristicsMuscle Nerve199316125412608413379

- GerschlagerWBrownPOrthostatic Tremor – a reviewHandb Clin Neurol201110045746221496602

- GanosCMaugestLApartisEThe long-term outcome of orthostatic tremorJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201687216717225770124

- WalkerFOMcCormickGMHuntVPIsometric features of orthostatic tremor: an electromyographic analysisMuscle Nerve1990139189222233849

- VeilleuxMSharbroughFWKellyJJWestmorelandBFDaubeJRShaky-legs syndromeJ Clin Neurophys19874304305

- BoroojerdiBFerbertAFoltysHKosinskiCMNothJSchwarzMEvidence for a non-orthostatic origin of orthostatic tremorJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry199066284288

- BrownPNew clinical sign for orthostatic tremorLancet19953463063077630259

- BrittonTCThompsonPDvan der KampWPrimary orthostatic tremor: further observations in six casesJ Neurol199223942092171597687

- DeuschlGBainPBrinMConsensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Ad Hoc Scientific CommitteeMov Disord199813suppl 3223

- AdebayoPBGunduzAKiziltanMEKiziltanGUpper limbs spread of orthostatic tremor following hip replacement surgeryNeurol India201462446246325237968

- UnciniAOnofriMBascianiMCutarellaRGambiDOrthostatic tremor: report of two cases and an electrophysiological studyMov Disord1989792119122

- Leu-SemenescuSRozeEVidailhetMMyoclonus or tremor in orthostatism: an under-recognized cause of unsteadiness in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord2007222063206917674413

- RigbyHBRigbyMHCavinessJNOrthostatic tremor: a spectrum of fast and slow frequencies or distinct entities?Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y)2015532426317042

- WilliamsERJonesREBakerSNBakerMRSlow orthostatic tremor can persist when walking backwardMov Disord20102579579720437546

- BakerMFisherKLaiMDuddyMBakerSSlow orthostatic tremor in multiple sclerosisMov Disord2009241550155319441134

- KimJSLeeMCLeg tremor mimicking orthostatic tremor as an initial manifestation of Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord199383973988341313

- CoffengSMHoffJITrompSCA slow orthostatic tremor of primary originTremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y)2013313

- PiboolnurakPYuQPPullmanSLClinical and neurophysiologic spectrum of orthostatic tremor: case series of 26 subjectsMov Disord200520111455146116037915

- YalthoTCOndoWGOrthostatic tremor: a review of 45 casesParkinsonism Relat Disord201420772372524736049

- GerschlagerWMünchauAKatzenschlagerRNatural history and syndromic associations of orthostatic tremor: a review of 41 patientsMov Disord200419778879515254936

- ContarinoMFWelterMLAgidYHartmannAOrthostatic tremor in monozygotic twinsNeurology2006661600160116717234

- BhattacharyyaKBDasDFamilial orthostatic tremor, and essential tremor in two young brothers: a rare entityAnn Indian Acad Neurol201316227627823956583

- SettaFMantoMUOrthostatic tremor associated with a pontine lesion or cerebellar diseaseNeurology199851923

- McAuleyJHBrittonTCRothwellJCFindleyLJMarsdenCDThe timing of primary orthostatic tremor bursts has a task-specific plasticityBrain200012325426610648434

- KraussJKWeigelRBlahakCChronic spinal cord stimulation in medically intractable orthostatic tremorJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2006771013101616735398

- WuYRAshbyPLangAEOrthostatic tremor arises from an oscillator in the posterior fossaMov Disord20011627227911295780

- NortonJAWoodDEDayBLIs the spinal cord the generator of 16-Hz orthostatic tremor?Neurology20046263263414981184

- SharottAMarsdenJBrownPPrimary orthostatic tremor is an exaggeration of a physiological response to instabilityMov Disord20031819519912539215

- FungVSSaunerDDayBLA dissociation between subjective and objective unsteadiness in primary orthostatic tremorBrain200112432233011157559

- KatzenschlagerRCostaDGerschlagerW[123I]-FP-CIT-SPECT demonstrates dopaminergic deficit in orthostatic tremorAnn Neurol20035348949612666116

- SpiegelJBehnkeSFussGBeckerGDillmannUEchogenic substantia nigra in patients with orthostatic tremorJ Neural Transm200511291592015526141

- WegnerFStreckerKBoecklerDIntact serotonergic and dopaminergic systems in two cases of orthostatic tremorJ Neurol20082551840184218821047

- TrocelloJMZanotti-FregonaraPRozeEDopaminergic deficit is not the rule in orthostatic tremorMov Disord2008231733173818661569

- SettaFJacquyJHildebrandJMantoMUOrthostatic tremor associated with cerebellar ataxiaJ Neurol19982452993029617712

- WillsAJThompsonPDFindleyLJBrooksDJA positron emission tomography study of primary orthostatic tremorNeurology1996467477528618676

- FeilKBöttcherNGuriFLong-term course of orthostatic tremor in serial posturographic measurementParkinsonism Relat Disord201521890591026071126

- RaudinoFMusciaFOsioMOrthostatic tremor and I123-FP-CIT-SPECT: report of a caseNeurol Sci20093036536619533286

- FitzGeraldPMJankovicJOrthostatic tremor: an association with essential tremorMov Disord1991660642005923

- GerschlagerWKatzenschlagerRSchragAQuality of life in patients with orthostatic tremorJ Neurol20032502021221512574953

- EvidenteVGAdlerCHCavinessJNGwinnKAEffective treatment of orthostatic tremor with gabapentinMov Disord1998138298319756154

- OnofrijMThomasAPaciCD’AndreamatteoGGabapentin in orthostatic tremor: results of a double-blind crossover with placebo in four patientsNeurology1998518808829748048

- RodriguesJPEdwardsDJWaltersSEGabapentin can improve postural stability and quality of life in primary orthostatic tremorMov Disord20052086587015719416

- RodriguesJPEdwardsDJWaltersSEBlinded placebo crossover study of gabapentin in primary orthostatic tremorMov Disord200621790090516532455

- WillsAJBrusaLWangHCBrownPMarsdenCDLevodopa may improve orthostatic tremor: case report and trial of treatmentJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19996668168410209189

- HellriegelHRaethjenJDeuschlGVolkmannJLevetiracetam in primary orthostatic tremor: a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover studyMov Disord201126132431243421953629

- FinkelMFPramipexole is a possible effective treatment for primary orthostatic tremor (shaky leg syndrome)Arch Neurol2000571519152011030807

- BertramKSirisenaDCoweyMHillAWilliamsDRSafety and efficacy of botulinum toxin in primary orthostatic tremorJ Clin Neurosci201320111503150523931935

- Gonzalez-AlegrePKelkarPRodnitzkyRLIsolated high-frequency jaw tremor relieved by botulinum toxin injectionsMov Disord20062171049105016602105

- YalthoTCOndoWGThalamic deep brain stimulation for orthostatic tremorTremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y)20111

- GuridiJRodriguez-OrozMCArbizuJSuccessful thalamic deep brain stimulation for orthostatic tremorMov Disord200823131808181118671286

- EspayAJDukerAPChenRDeep brain stimulation of the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus in medically refractory orthostatic tremor: preliminary observationsMov Disord200823162357236218759339

- ContarinoMFBourLJSchuurmanPRThalamic deep brain stimulation for orthostatic tremor: clinical and neurophysiological correlatesParkinsonism Relat Disord20152181005100726096797