Abstract

Different forms of optic neuropathy causing visual impairment of varying severity have been reported in association with a wide variety of infectious agents. Proper clinical diagnosis of any of these infectious conditions is based on epidemiological data, history, systemic symptoms and signs, and the pattern of ocular findings. Diagnosis is confirmed by serologic testing and polymerase chain reaction in selected cases. Treatment of infectious optic neuropathies involves the use of specific anti-infectious drugs and corticosteroids to suppress the associated inflammatory reaction. The visual prognosis is generally good, but persistent severe vision loss with optic atrophy can occur. This review presents optic neuropathies caused by specific viral, bacterial, parasitic, and fungal diseases.

Introduction

Optic nerve involvement with variable visual impairment has been associated with a wide variety of infectious disorders.Citation1–Citation3 It may present as anterior optic neuritis, also called papillitis (swollen optic disc), retrobulbar optic neuritis (normal optic disc), neuroretinitis (optic disc edema with macular star), anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, or as another form of optic neuropathy.

The pathogenesis of infectious optic neuropathies remains speculative. Direct involvement of the optic nerve by a pathogen and indirect involvement with inflammatory, degenerative, or vascular mechanisms might contribute to the development of optic nerve involvement.Citation1–Citation3

The purpose of this article is to review optic neuropathies caused by specific viral, bacterial, parasitic, and fungal diseases.

Viral optic neuropathies

Herpes viruses

Herpes simplex virus (types 1 and 2)

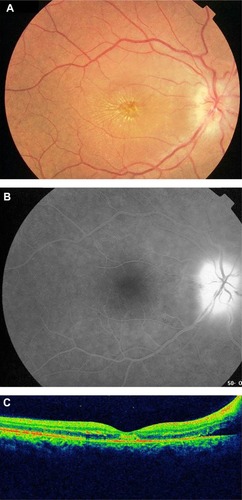

Optic neuropathy can occur in association with herpes simplex virus encephalitis, as well as with acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome. ARN syndrome is defined by a combination of clinical features, including areas of retinal necrosis, occlusive vasculopathy, vitritis, and anterior chamber inflammation. This entity is characterized by a high rate of complications, including retinal detachment, optic nerve or macular involvement, and fellow eye disease.Citation4 Optic neuropathy has been reported in 11%–57% of ARN cases.Citation4–Citation6 Optic nerve involvement in ARN may occur before, after, or simultaneously with retinal necrosis and usually causes a rapid and severe vision loss.Citation7–Citation9 It may present as papillitis (), neuroretinitis, retrobulbar optic neuropathy, or optic disc atrophy that may develop several weeks after acute ARN.Citation4 Several mechanisms have been postulated for the pathogenesis of optic nerve involvement in ARN, including intraneural vasculitis, compressive ischemia of the optic nerve, and inflammation and necrosis due to direct herpes virus infection.Citation4

Figure 1 Fundus photograph of the left eye of a patient with HSV1-associated acute retinal necrosis shows marked optic disc edema associated with peripheral areas of retinal necrosis and retinal hemorrhages.

Acyclovir appears to be efficacious in the treatment of ARN-associated optic neuropathy. The role of systemic corticosteroids in improving visual outcome is not well established. However, it is important to ensure that the infectious disease has been properly covered with antiviral therapy prior to initiation of corticosteroid therapy.Citation4

Varicella zoster virus

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) is responsible for two distinct clinical entities, ie, varicella zoster and herpes zoster. Varicella, often occurring in childhood, is the primary infection, and herpes zoster, most commonly seen among elderly or immunocompromised patients, is due to recurrent disease. Papillitis associated with varicella has been reported to occur in children and adults, during or after the onset of varicella rash.Citation10–Citation16 Visual loss is usually bilateral and can be severe. A few cases of papillitis preceding the onset of varicella rash have been reported.Citation13 Visual outcome of varicella-associated papillitis is generally good, with complete restoration of visual acuity, although there may be residual optic disc pallor.Citation10–Citation13 However, severe persistent visual loss has been reported.Citation14,Citation15

The role of corticosteroid therapy in the management of varicella-associated optic neuritis is controversial. Systemic corticosteroids have been advocated to accelerate visual recovery, but there are reports of patients who recovered spontaneously without corticosteroid therapy or had severe residual visual loss despite corticosteroid therapy.Citation10,Citation14,Citation15 The role of antiviral therapy is not established either.

Optic neuropathy in the form of anterior or retrobulbar optic neuritis is a rare complication of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. It may occur simultaneously to the acute vesicular rash or, more frequently, as a postherpetic complication, weeks to months after disease onset.Citation17–Citation26 Visual acuity may vary from severe bilateral impairment to moderate unilateral impairment, with a normal or edematous optic disc. Good recovery from herpes zoster ophthalmicus optic neuritis with systemic acyclovir and corticosteroid therapy has been reported; however, cases of visual loss due to optic disc atrophy may occur.Citation18 Giant cell arteritis is the main differential diagnosis of VZV-associated optic neuropathy, mainly in elderly patients without skin rash. A normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level along with a negative temporal artery biopsy can rule out giant cell arteritis. Optic nerve involvement in herpes zoster might be caused by direct infection of the nerve or an ischemic process due to inflammatory thrombosis.Citation18 Other VZV-related ocular conditions that may be accompanied by optic nerve involvement include ARN syndrome and progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN). PORN is a necrotizing herpetic retinopathy usually seen in immunocompromised patients and is caused by VZV. Optic nerve involvement has been reported in 17% of eyes with PORN including optic disc edema and optic disc atrophy.Citation24 Retrobulbar optic neuropathy has been reported to precede the development of PORN.Citation25,Citation26 Eyes with PORN-associated optic neuropathy have a poor visual outcome despite aggressive antiviral therapy.

Cytomegalovirus (herpesvirus 5)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) papillitis has been reported in 4%–14% of patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome and CMV retinitis.Citation27–Citation30 Several cases of CMV optic neuropathy in immune-compromised patients unrelated to CMV retinitis have also been described, including isolated optic neuritis, retrobulbar optic neuritis associated with meningoencephalitis and bilateral PORN, and bilateral retrobulbar optic neuritis following haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.Citation31–Citation35 A few cases of bilateral CMV papillitis without associated retinitis have been reported in young immunocompetent patients, with good recovery after antiviral therapy with or without associated corticosteroid therapy.Citation36–Citation38 The prognosis of CMV-associated papillitis remains guarded despite aggressive antiviral therapy with or without associated corticosteroid therapy, with final visual acuity less than 20/68 in almost all patients.Citation27–Citation30

Epstein-Barr virus (herpesvirus 6)

The Epstein-Barr virus causes infectious mononucleosis in childhood and adolescence. It is also associated with Burkitt’s lymphoma, primary cerebral lymphoma in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Optic nerve involvement in Epstein-Barr virus infection is generally bilateral and may include papillitis, retrobulbar optic neuritis, and neuroretinitis.Citation39–Citation41 A few cases of chiasmal involvement have been also reported.Citation42,Citation43 Most cases had a good visual outcome after oral or intravenous corticosteroid therapy.Citation39–Citation41

Human immunodeficiency virus

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus and a member of the genus Lentivirus within the family Retroviridae.Citation2 Primary HIV optic nerve involvement is rare and may be the presenting manifestation of the disease.Citation44 However, it should remain a diagnosis of exclusion to be considered only after ruling out opportunistic infections and neoplastic conditions.

HIV optic neuropathy may be unilateral or bilateral and may present as retrobulbar optic neuropathy, papillitis, ischemic optic neuropathy, or optic disc pallor.Citation2,Citation44–Citation50 Inflammatory, vascular, and degenerative mechanisms have been postulated to play a role in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated optic neuropathy. Histopathologic studies of affected optic nerves have demonstrated axonal degeneration and demyelination, and glial changes involving hypertrophic astrocytes, vacuolated oligodendrocytes, and mononuclear phagocyte series cells.Citation51,Citation52 These findings suggest that optic nerve degeneration may be mediated by HIV-infected macrophages. HIV-associated optic neuropathy may be treated with antiretroviral drugs, corticosteroids, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists.Citation44,Citation45,Citation50

Arboviruses

West Nile virus

West Nile virus (WNV) is an enveloped single-stranded RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus that is transmitted to humans by an infected mosquito vector of the genus Culex, with wild birds serving as its reservoir.Citation53 Most human infections are subclinical or manifest as febrile illness.Citation53 However, severe neurologic disease, frequently associated with advanced age and diabetes, was reported to occur in less than 1% of patients.Citation53 A bilateral or rarely unilateral multifocal chorioretinitis with linear clustering of chorioretinal lesions is the most common finding, occurring in almost 80% of patients with acute WNV infection associated with neurologic illness.Citation54,Citation55

Optic nerve involvement, with or without associated chorioretinitis, has been described in association with WNV infection.Citation2,Citation53–Citation61 It may present in the form of optic neuritis, neuroretinitis, optic disc swelling, optic disc staining on fluorescein angiography, or papilledema due to intracranial hypertension caused by meningoencephalitis.Citation2,Citation53–Citation62

To date, there is no effective treatment for WNV infection. In cases of severe systemic disease, intensive supportive therapy is indicated. The overall prognosis of optic nerve involvement in WNV infection is good, although persistent visual loss may occur due to optic atrophy.

Chikungunya

Chikungunya fever is an emergent infectious disease caused by Chikungunya virus, and transmitted by the bite of the infected Aedes mosquitoes. Systemic involvement includes acute fever with headache, fatigue, myalgia, diffuse maculopapular rash, bleeding from the nose or gums, peripheral edema, joint pain neurological signs, acute hepatic failure, and multiorgan failure.Citation56 Ocular involvement is common, and may include episcleritis, anterior uveitis, retinitis, retinochoroiditis, mild vitritis, occlusive vasculitis, central retinal artery occlusion, exudative retinal detachment, and optic nerve involvement.Citation56 Optic neuropathy is one of the most important causes of acute vision loss in patients with Chikungunya. It may occur simultaneously with systemic infection, suggesting a direct viral mechanism, or later in the course of the disease, suggesting an immune-mediated reaction.Citation63 Various clinical forms of optic neuropathy have been described including unilateral or bilateral papillitis, retrobulbar neuritis, and neuroretinitis.Citation56,Citation63–Citation69 The overall visual outcome of Chikungunya-associated optic neuritis is good, and corticosteroid therapy seems to accelerate recovery when initiated at an early stage of the disease.Citation66,Citation67

Dengue fever

Dengue fever is an arthropod vector-borne disease caused by the Dengue virus, a Flavivirus transmitted by the Aedes mosquito.Citation56 Systemic disease may range from mild febrile illness to life-threatening disease, such as Dengue hemorrhagic fever and Dengue shock syndrome.Citation56 Ocular involvement may include subconjunctival hemorrhage, anterior uveitis, vitritis, retinal hemorrhages, retinal vascular sheathing, yellow subretinal dots, retinal pigment epithelium mottling, foveolitis, retinochoroiditis, choroidal effusion, panophthalmitis, oculomotor nerve palsy, and optic nerve involvement.Citation56,Citation70 Optic nerve involvement may include neuroretinitis, optic disc swelling, and optic neuritis.Citation56,Citation70–Citation78 The reported incidence of optic neuritis ranges from 0% to 1.5%.Citation71 Optic neuritis may be bilateral or unilateral, isolated, or associated with Dengue maculopathy. Spontaneous visual recovery is possible in Dengue fever-associated optic neuritis, but severe permanent visual loss has been reported.Citation72,Citation76 Self-limited single cases of bilateral neuroretinitis and neuromyelitis optica have been also reported.Citation77,Citation78

Rift valley fever

Rift valley fever is an arthropod-borne viral disease caused by Bunyaviridae and transmitted to humans through a bite by infected mosquitoes or through direct contact with infected animals.Citation56 Systemic involvement includes fever with a biphasic temperature curve, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, and gastrointestinal disturbances.Citation56 Severe clinical presentations may include a hemorrhagic fever with liver involvement, thrombocytopenia, icterus and bleeding tendencies, and a neurological involvement with encephalitis after a febrile episode with confusion and coma.Citation56

Ocular involvement includes anterior uveitis, macular or paramacular necrotizing retinitis, retinal hemorrhages, vitritis, retinal vasculitis, and optic nerve involvement.Citation56,Citation79,Citation80 Optic nerve involvement includes optic disc edema, reported in 15% of patients in the acute phase, and optic atrophy, reported in 20% of cases during follow-up.Citation79

Other viruses

Influenza

A few cases of optic neuritis in the setting of influenza infection have been reported. The visual outcome was good after corticosteroid therapy.Citation81–Citation85 Neuroretinitis and neuromyelitis optica with a self-limited course have also been reported.Citation83,Citation85 Optic nerve involvement may be related to direct viral infection or due to an autoimmune event triggered by infection. The association with other neurological complications, including extrapyramidal syndrome, Guillain-Barré syndrome, myelitis and myositis,Citation82 and improvement after systemic corticosteroid therapy may argue in favor of the latter hypothesis.

Mumps

Mumps is an acute contagious viral disease of the parotid salivary glands, characterized by swelling of the affected parts, fever, and pain beneath the ear, which commonly affects children. Optic nerve involvement is rare in mumps, and may include papillitis, retrobulbar optic neuritis, and neuroretinitis.Citation86–Citation90 Optic nerve involvement is usually bilateral and occurs 2–5 weeks after parotiditis.Citation86,Citation87 Visual impairment is usually severe, with recovery during the following month, but there may be permanent vision loss with optic atrophy.Citation86

Rubella

Rubella is a common infectious disease caused by the rubella virus. The disease is generally mild in children but has serious consequences in pregnant women, causing fetal death or congenital rubella syndrome. Symptoms include rash, low fever, nausea, and mild conjunctivitis. The rash, occurring in 50%–80% of cases, starts on the face and neck and then progress down the body. Swollen lymph glands behind the ears and in the neck are the most characteristic clinical feature of rubella infection. Infected adults, more commonly women, may develop arthritis and painful joints that usually last from 3 to 10 days.

A few cases of optic neuritis related to rubella infection have been reported.Citation91–Citation93 A delayed onset of optic neuritis after the initial infection and a prompt response to corticosteroid therapy may suggest involvement of an immune process in the pathogenesis of post-rubella optic neuritis.

Measles

Measles is a highly contagious infection caused by the measles virus. Signs and symptoms of measles include cough, runny nose, sore throat, fever, and a red, blotchy skin rash. Optic nerve involvement, including optic neuritis and retrobulbar optic neuropathy, is a rare complication of measles that may affect children or adults with or without associated encephalomyelitis.Citation94–Citation98 Optic neuritis usually occurs about 1 week after the onset of initial symptoms. The prognosis is generally favorable with recovery of good visual acuity after corticosteroid therapy.Citation94–Citation98

Bacterial optic neuropathies

Cat scratch disease

Cat scratch disease (CSD), or ocular Bartonellosis, is a worldwide zoonotic infectious disease caused by the Gram-negative bacillus Bartonella henselae, and is transmitted to humans by the scratches, licks, or bites of an infected cat, particularly a kitten.Citation99 The systemic illness, which occurs mainly in children and young adults, is typically self-limited and usually presents as a flu-like syndrome and a tender lymphadenitis involving the lymph nodes draining dermal or conjunctival sites of inoculation.Citation100 Ocular involvement can occur in 5%–10% of patients with CSD.Citation101 The eye can be involved either with the primary inoculation complex, resulting in the Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome or by hematogenous spread leading to an array of ocular manifestations, including neuroretinitis, inner retinitis, and occlusive vasculitis.Citation99,Citation101

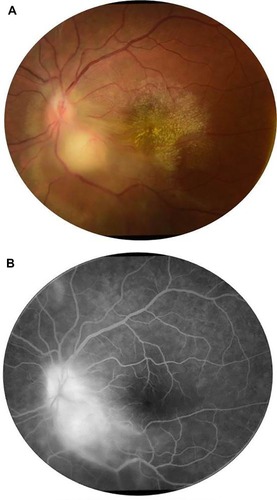

Neuroretinitis was found to be the most characteristic and common posterior segment manifestation of CSD, occurring in 49%–71% of cases.Citation102–Citation105 Conversely, CSD is the most common identifiable cause of neuroretinitis (two thirds of cases).Citation99,Citation100 The ocular condition is usually unilateral, although bilateral cases have also been reported. The onset of visual symptoms usually follows the inoculation by approximately 4 weeks and the systemic symptoms by 2–3 weeks. Typically, the patient presents with decreased vision, with visual acuity ranging from 20/20 to light perception. A relative afferent papillary defect, dyschromatopsia, and a visual field defect are usually seen. Mild anterior chamber and vitreous inflammation is also common. Fundus examination typically shows optic disc edema associated with a partial or complete macular star (). The optic disc edema occurs approximately 1 week prior to the development of stellate maculopathy, which therefore may be absent at the time of initial presentation. The optic nerve involvement leads to peripapillary retinal thickening and, frequently, an exudative retinal detachment.Citation106 Intraretinal hemorrhages or telangiectatic vessels may be seen.Citation102 A multifocal inner retinitis or chorioretinitis, typically juxtavascular in location, may accompany the disc swelling.Citation103,Citation104 Rarely, a large inflammatory mass or exudate of the optic nerve head may be seen.Citation107 Fluorescein angiography shows leakage from the optic disc with no evidence of capillary abnormality in the macular area.Citation108 Optical coherence tomography may be helpful in detecting subclinical serous retinal detachment. Neuroretinitis usually has a self-limited course. Most patients recover excellent visual acuity over a period of several weeks to months (20/40 or better in 65%–80% of eyes).Citation104,Citation105,Citation109,Citation110 However, significant visual morbidity may occur.Citation105 The macular star usually resolves in approximately 8–12 weeks, but it may be present for up to 1 year. A few patients may be left with mild pallor of the optic disc.Citation111 Retinal pigment epithelial changes may also develop after resolution of macular hard exudates. The diagnosis of CSD is based on clinical findings and laboratory tests, including indirect fluorescent antibody test, enzyme-linked immunoassay, Western blot, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays.Citation99,Citation100,Citation112–Citation114

Figure 2 (A) Fundus photograph of the right eye of a patient with cat scratch disease showing optic disc edema and a complete macular star consistent with a diagnosis of neuroretinitis. (B) Late-phase fluorescein angiogram shows optic disc leakage with no abnormalities in the macular area. (C) Optical coherence tomography shows peripapillary serous retinal detachment.

Until now, there are no guidelines for the treatment of CSD or its ocular complications. Treatment is recommended for severe ocular or systemic complications of B. henselae infection. A typical regimen consists of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 4–6 weeks in immunocompetent patients and 4 months in immunocompromised patients.Citation115–Citation117 It seems to shorten the course of infection and hasten visual recovery.Citation104 However, a few other studies suggest that there is no association between final visual acuity and the use of systemic antibiotics.Citation105,Citation110 The role of corticosteroids in the treatment of ocular CSD remains unclear.Citation111 Some authors recommend the early use of corticosteroids as they may hasten recovery and other authors failed to support the use of corticosteroid therapy in CSD optic neuropathy.Citation105,Citation118

Tuberculosis

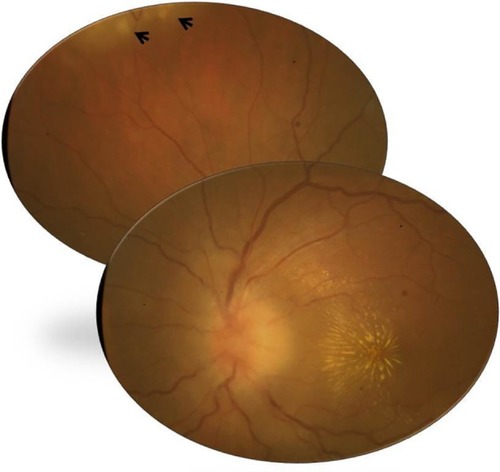

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, mainly affecting the lungs, and is histologically characterized by caseating granulomas. Intraocular TB usually occurs in the absence of evident active systemic disease.Citation119 TB may affect all ocular tissues and may manifest as anterior granulomatous uveitis, choroiditis, retinal vasculitis, subretinal abscess, endophthalmitis, panophthalmitis, or optic neuropathy.Citation119,Citation120 Optic nerve involvement is a common complication of ocular TB. It may result from direct mycobacterial infection, by contiguous spread from the choroid or hematogenous dissemination, or from a hypersensitivity to the infectious agent.Citation120 The clinical spectrum of tuberculous optic neuropathy is wide, with papillitis (51.6%), neuroretinitis (14.5%), and optic nerve tubercle (11.3%; ) being the most common clinical form.Citation121 Associated posterior uveitis or panuveitis may be seen in almost 90% of cases. Extraocular tuberculosis, particularly pulmonary and meningeal, could be associated in more than one third of patients.Citation121 There are reports of compressive optic neuropathy, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, optic atrophy, and optic chiasmatic arachnoiditis.Citation122–Citation132 TB should also be considered in the differential diagnosis of apparently isolated papillitis or neuroretinitis, particularly in patients from endemic areas. In such cases, indocyanine green angiography may show subclinical choroidal involvement.Citation121 Tubercular choroidal lesions may develop later as well in the course of optic neuropathy.Citation127 Unilateral optic disc swelling may be secondary to tubercular posterior scleritis.Citation122 Patients with central nervous system TB, particularly tubercular meningitis (hydrocephalus), optic chiasmatic arachnoiditis, and optochiasmatic tuberculoma, may develop papilledema and, in advanced cases, bilateral optic atrophy.Citation123,Citation124,Citation132

Figure 3 (A) Fundus photograph of the left eye of a patient with ocular tuberculosis shows a juxtapapillary choroidal granuloma with associated papillitis. Note the exudative retinal detachment surrounding the choroidal granuloma and the macular exudates. (B) Late-phase fluorescein angiogram shows leakage of the optic disc and granuloma.

The diagnosis of tuberculous optic neuropathy is often presumptive, based on suggestive ocular features, positive results of ocular or systemic investigations, exclusion of other specific causes of uveitis, and a positive response to anti-tubercular treatment.Citation119

Management of ocular TB involves the use of anti-tubercular treatment for 9–12 months.Citation119 The use of adjunctive systemic corticosteroid therapy may help reduce the inflammatory reaction, but its beneficial effect and safety remains controversial.Citation120,Citation121,Citation133 Tuberculous arachnoiditis may be treated with neurosurgical decompression of the anterior visual pathways.Citation131 Visual outcomes of tuberculous optic neuropathy are generally good, with 76.7% of eyes achieving final visual acuities of 20/40 or better, and complete or partial recovery of visual field defects in 63.2% of eyes.Citation121

Syphilis

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, and is known as “the great mimicker” due to its wide variety of clinical presentations.Citation134,Citation135 A broad spectrum of ophthalmic manifestations may occur in both acquired and congenital syphilis, including uveitis, scleritis, episcleritis, dacyroadenitis, interstitial keratitis, vitritis, chorioretinitis, retinal vasculitis, serous retinal detachment, optic neuropathy, and cranial nerve palsies.Citation135 Ocular involvement is strongly suggestive of central nervous system disease and should be considered synonymous with neurosyphilis.Citation134,Citation135 Unilateral or bilateral optic neuropathy may occur in secondary and tertiary syphilis, often with minimal or no anterior segment inflammation. It may manifest as papillitis, perineuritis, chiasmal syndrome, gumma of the optic disc, neuroretinitis, and optic disc cupping.Citation136–Citation142 Serodiagnosis is usually based on the results of both nontreponemal antigen tests, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and rapid plasma reagin, and specific treponemal antigen tests, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay and T. pallidum particle agglutination test.Citation143 PCR analysis of intraocular and/or cerebrospinal fluid may be useful to confirm syphilitic infection.Citation144 The recommended treatment for ocular syphilis, as for neurosyphilis, involves intravenous penicillin G or intramuscular procaine penicillin for 10–14 days along with oral probenecid.Citation145 Systemic or periocular corticosteroids may be a useful adjunct to antimicrobial agents.Citation146

Lyme disease

Lyme disease (LD) or Lyme borreliosis is an emerging tick-borne infection caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. The spirochete is transmitted to humans by tick bites of the genus Ixodes during the peak season of May to September.Citation147 The disease has a bimodal distribution, with peaks in children aged 5–14 years and in adults aged 50–59 years.Citation147,Citation148 Three clinical stages of LD are described, including early (local), disseminated, and late (persistent) stages.Citation147 A protean of ocular manifestations may occur and vary with each stage. It may include conjunctivitis, keratitis, posterior scleritis, dacryoadenitis, orbital myositis, uveitis, retinal vasculitis, multifocal choroiditis, and neuro–ophthalmic manifestations.Citation148

Optic neuropathy has been reported to occur in the early and disseminated stages of LD, most often with bilateral involvement. Besides papilledema associated with meningoencephalitis in children, optic nerve involvement, including papillitis, neuroretinitis, ischemic optic neuropathy, optic atrophy, and chiasmal syndrome, has been described in patients with positive Lyme serology, but causality links remains controversial.Citation149–Citation156 In endemic areas, where residents are often seropositive for Borrelia but are asymptomatic, a causal relationship between the disease and the optic neuropathy is difficult to establish.Citation156 The diagnosis of LD is based on history, clinical presentation, and supportive serology. Furthermore, other causes of the disease should be excluded. Lack of standardization of cut-off value and cross-reactivity with other spirochetes may lead to false positive and false negative test results. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend a two-step protocol for the diagnosis of active disease or previous infection: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for immunoglobulin (Ig)M and IgG, followed by Western immunoblot testing.Citation157 PCR analysis of a variety of tissues, including ocular fluids, can be useful. Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis with demonstration of intrathecal synthesis of specific antibodies is a mainstay of the diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis in Europe.Citation147 The route and duration of antibiotic treatment for presumed optic nerve involvement in LD has not been established. However, optic neuropathy associated with LD is best regarded as a manifestation of central nervous system involvement and requires intravenous antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone (2 g intravenously once daily) for at least 3 weeks.

Rickettsioses

Rickettsioses are zoonoses due to a group of obligate intracellular small Gram-negative bacteria and are distributed worldwide. Most of them are transmitted to humans by the bite of contaminated arthropods, such as ticks.Citation158 A recent syndromic classification distinguishes three major categories of rickettsial diseases: the exanthematic rickettsioses syndrome with a low probability of inoculation eschar; the rickettsioses syndrome with a probability of inoculation eschar; and their variants.Citation159 Systemic disease is characterized by the triad of high fever, headache, and skin rash, with or without associated inoculation eschar, termed “tache noire” or dark spot.

Ocular involvement in rickettsioses is common, with retinitis, retinal vasculitis, and optic nerve involvement being the most common ocular manifestations.Citation160–Citation164 Other findings have been described, including Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, conjunctivitis, keratitis, non-granulomatous anterior uveitis, panuveitis, cranial nerve palsies, and endophthalmitis.Citation160–Citation164 Rickettsial optic nerve involvement may present in the form of optic disc swelling, optic disc staining on fluorescein angiography, optic neuritis, neuroretinitis (), ischemic optic neuropathy, papilledema, and optic atrophy ().Citation165–Citation171

Figure 4 Fundus photograph of the left eye of a patient with rickettsial disease shows optic disc edema and a macular star. Note the presence of foci of inner retinitis in the superior periphery (arrows).

Figure 5 Fundus photograph of the left eye of a patient with a history of rickettsial infection shows optic disc atrophy secondary to ischemic optic neuropathy.

The exact mechanism of optic neuropathy is unknown, but it may be due to an immune-mediated inflammation or ischemia from endothelial injury and tissue necrosis, reflecting the tropism of rickettsial organisms for optic disc vasculature.Citation170,Citation171 Diagnosis of rickettsial infection is made on the basis of epidemiological data, history, systemic symptoms and signs, and the pattern of ocular involvement. It is usually confirmed by positive indirect immunofluorescent antibody test results. Although ophthalmic manifestations of rickettsial disease have a self-limited evolution in most patients, severe persistent visual loss may occur, mainly due to optic neuropathy.Citation160,Citation170,Citation171 The role of antibiotic therapy, as well as that of oral corticosteroids, in the course of optic neuropathy remains unknown.Citation159,Citation165

Q fever

Q fever is a worldwide zoonosis caused by Coxiella burnetii, an obligate Gram-negative intracellular bacteria.Citation172 Transmission to humans occurs primarily through inhalation of aerosols from contaminated soil or animal waste. Other rare routes of transmission include tick bites, ingestion of unpasteurized milk or dairy products, and human-to-human transmission.Citation172 The disease has several manifestations, and may be acute or chronic.

Ocular involvement, including optic neuropathy, has rarely been described in the course of Q fever.Citation173–Citation180 The mechanism of optic nerve involvement may be an autoimmune or post-infectious phenomenon.Citation179 In most reported cases, optic neuritis was bilateral and occurred either in the acute or chronic stage of the disease. Associated neurological manifestations, including confusion, meningoencephalitis, polyradiculoneuropathy, and cranial nerve palsies, may be seen.Citation179,Citation180 The diagnosis of Q fever can be made on the basis of serological testing. Persistent visual loss has been reported in about half of cases.Citation179,Citation180 The role of antibiotic and steroid therapy in the management of optic neuritis associated with Q fever remains unclear.

Whipple’s disease

Whipple’s disease is a rare chronic multisystem disease caused by a Gram-positive bacillus, the Tropheryma whippleii.Citation181 Ocular involvement, including keratitis, uveitis, retinal vasculitis, cranial nerve palsies, nystagmus, ptosis, and ophthalmoplegia, occurs in about 5% of patients, usually late in the course of the disease.Citation181–Citation183 Other manifestations may include supranuclear gaze palsy and oculomasticatory myoarrhythmia. A few cases of optic neuritis, optic disc edema with subsequent optic atrophy, and orbital involvement with visual loss have been reported.Citation183–Citation185 All ocular signs may occur in the absence of gastrointestinal, neurologic, or other systemic manifestations.Citation182 The diagnosis of Whipple’s disease is challenging, mainly based on cytologic and molecular analysis.Citation183 Untreated, the disease can be fatal. Systemic trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole associated with rifampin, for at least 1 year, is the treatment of choice in central nervous system or ocular Whipple’s disease. A prolonged low-dose antibiotic regimen to prevent relapse, neurologic involvement, and death is recommended.Citation183 Corticosteroids are usually not required to control intraocular inflammation during antibiotic treatment.Citation183

Brucellosis

Brucellosis is a worldwide zoonosis due to facultative intracellular Gram-negative bacteria, Brucella species.Citation186 The disease might be acute or chronic, and a multisystemic involvement occurs in 10%–15% of cases.Citation187 Although ocular involvement is uncommon in brucellosis, any ocular structure may be involved, with a broad spectrum of clinical findings, including keratitis, uveitis, choroiditis, episcleritis, endophthalmitis, dacryoadenitis, and optic neuropathy.Citation188–Citation200 Optic nerve involvement, including optic neuritis and papilledema, has been described in about 10% of patients with ocular brucellosis.Citation189,Citation192,Citation193 It seems that optic neuropathy in brucellosis is secondary to meningeal inflammation (neurobrucellosis) and subsequent axonal degeneration.Citation182,Citation183 Ischemic, vasculitic, and immune-mediated mechanisms have also been suggested.Citation188,Citation199 The diagnosis of brucellosis relies on clinical features supported by microbiological and serological tests.Citation186,Citation187 The visual prognosis of brucella-related optic neuropathy is usually good after an appropriate course of antibiotic and steroid therapy. However, severe cases with permanent visual impairment have been described.Citation199

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a waterborne zoonotic infection caused by a Gram-negative spirochete of the genus Leptospira.Citation201 Humans contract the disease by contact with infected urine, tissues, or water. The systemic disease has a biphasic course, with an initial leptospiremic acute phase followed by the immune phase of illness.Citation201,Citation202 Ocular involvement may occur in both the acute and second phase of the illness. While in the former phase conjunctival chemosis and scleral icterus are the main ocular findings, the latter immune phase has a broad variety of ocular manifestations, including keratitis, nongranulomatous uveitis, retinal vasculitis, cranial nerves palsies, and optic neuropathy.Citation201–Citation207 Optic nerve involvement may present in the form of optic disc hyperemia (seen in 3%–64% of cases), optic neuritis, papillitis, or neuroretinitis.Citation202–Citation204,Citation206,Citation207

Diagnosis can be established on the basis of laboratory tests including microagglutination test, isolation of the organism from body fluids, and serological and PCR-based assays.Citation201–Citation203 Despite the lack of evidence, use of systemic antibiotic therapy is common, whereas corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for ocular involvement.Citation202,Citation203,Citation207

Leprosy

Leprosy is a chronic granulomatous infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae. Ocular involvement may include lagophthalmos, corneal involvement, cataract, uveitis, dacryoadenitis, eyelid involvement, and optic nerve involvement.Citation208 Optic nerve involvement in the form of papillitis or optic atrophy is a rare complication of leprosy.Citation209–Citation211 The pathogenesis of leprosy-associated optic neuropathy is unclear. It might be the result of direct bacterial infection, autoimmune reaction, ischemia, or a combination of these mechanisms.Citation210,Citation211 Treatment of leprosy relies on systemic dapsone and rifampin. Corticosteroids have been used for the management of leprosy-associated optic neuropathy.Citation210

Other bacterial agents

Occasional cases of optic neuropathies have been described in other bacterial infections including Ehrlichiosis, anthrax, typhoid fever, pertussis, beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection, and meningococcal, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia, and Klebsiella pneumoniae infections.Citation212–Citation222

Optic neuropathies associated with orbital infections

The term “orbital infections” refers to an invasive bacterial infection of the periorbital and orbital structures.Citation223 Orbital infections can develop by extension of infection from adjacent paranasal sinuses or upper respiratory infection, ocular and adnexal structures, direct inoculation as a result of trauma or surgery, or hematogenous spread in the setting of bacteremia.Citation224 Optic nerve involvement may occur in the setting of complicated retroseptal infection in the form of orbital abscess or cavernous sinus thrombosis. It may result from direct compression of the optic nerve as well as the nutrient vessels (ischemic optic neuropathy) or dissemination of infection (septic optic neuropathy).Citation225

Clinical findings may include decreased visual acuity, afferent pupillary defect, optic disc swelling, retinal venous dilatation, ptosis, severe directional proptosis, periorbital edema, chemosis, ophthalmoplegia, headache, generalized sepsis, nausea, vomiting, and high fever.Citation223 Cranio-orbital high-resolution contrast-enhanced computed tomography is the gold standard for diagnosis and management of orbital infections. Treatment involves use of systemic broad-spectrum antibiotics, and is associated with surgical therapy in severe forms of postseptal infection.Citation226 The role of corticosteroids in the management of complicated orbital infections remains controversial. The prognosis depends on the rapidity of treatment, but persistent visual loss resulting from rapidly progressing optic neuropathy often occurs.

Parasitic optic neuropathies

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis is an infection caused by the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii and is distributed worldwide. Ocular toxoplasmosis is the most common infectious posterior uveitic entity. It typically presents in the form of active unifocal retinochoroiditis usually associated with adjacent old retinochoroidal scar and significant vitritis. Atypical presentations of ocular toxoplasmosis mainly include multifocal retinochoroiditis, which is common in immunocompromised individuals, punctate outer or inner retinitis, intraocular inflammation without retinochoroiditis, unilateral pigmentary retinopathy simulating retinitis pigmentosa, Fuchs’-like anterior uveitis, and scleritis.Citation227 Reactive optic disc hyperemia usually accompanies active toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Lesions adjacent to the optic disc may produce significant morbidity leading to central vision loss or sectorial visual field defects.Citation224 In fact, scars within one disc diameter of the disc are more likely to be associated with absolute defects breaking out to the periphery. Other clinical forms of toxoplasmic optic neuropathy include neuroretinitis, papillitis causing vision loss associated with a distant active retinochoroidal lesion, and isolated anterior optic neuritis.Citation228–Citation239

The diagnosis of toxoplasmic optic neuritis may be challenging in the absence of an active or inactive retinochoroidal lesion. Diagnosis of toxoplasmic optic neuropathy requires a high index of clinical suspicion and the use of appropriate laboratory investigations. A positive assay for IgG does not confirm the diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis, given the high rate of seropositivity in the normal population in most countries. The presence of high IgM and/or IgA titer or a rising IgG titer indicates recently acquired infection. A negative serology can exclude the diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. The Goldmann-Witmer coefficient and the Western blot technique are used to demonstrate local production of antibodies in aqueous humor or rarely in vitreous fluid. Detection of toxoplasma DNA in ocular fluids by PCR is helpful in atypical cases.

The mechanism of the optic nerve involvement in ocular toxoplasmosis may be the result of direct infection of the optic disc by T. gondii or an indirect inflammatory process.Citation228

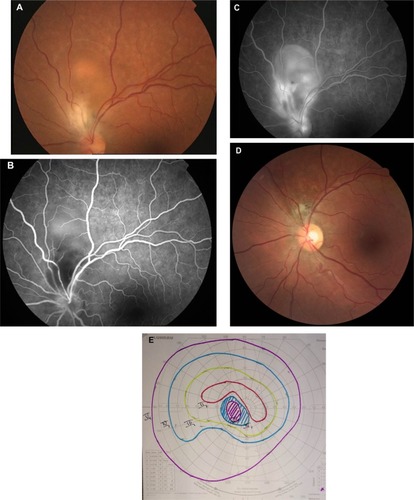

Management of toxoplasmosis-associated optic neuropathy involves the use of a combination of antiparasitic therapy and corticosteroids. The standard treatment includes pyrimethamine, given in a loading dose of 100 mg on day 1 followed by 50 mg daily (25 mg in children) and sulfadiazine 4 g/day.Citation227 Folinic acid (25 mg per os two or three times a week) is added to prevent bone marrow suppression, which may result from pyrimethamine therapy. Other therapeutic alternatives include oral or intravitreal clindamycin, spiramycin, and azithromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The overall visual outcome of toxoplasmosis-associated optic nerve involvement is good after systemic antitoxoplasmosis treatment and corticosteroids.Citation228 However, scars within one disc diameter of the optic disc are more likely to be associated with absolute defects leading to considerable field loss ().Citation240

Figure 6 (A) Fundus photograph of the left eye of a patient with ocular toxoplasmosis shows a juxtapapillary active area of retinochoroiditis adjacent to a pigmented scar with associated serous retinal detachment. (B) Early-phase fluorescein angiogram shows hypofluorescence of both active and old foci. (C) Late-phase fluorescein angiogram shows peripheral hyperfluorescence and persistent central hypofluorescence of the active focus of retinochoroiditis with late pooling of dye in the subretinal space and optic disc hyperfluorescence. (D) Fundus photograph 6 months later shows a small atrophic retinochoroidal scar that replaced the active toxoplasmic lesion with a localized defect of the retinal nerve fiber layer as wedge-shaped area running toward the optic disc. (E) Goldmann perimetry shows a persistent scotoma.

Toxocariasis

Toxocariasis is a zoonotic disease caused by the infestation of humans with second-stage larvae of the dog nematode Toxocara canis or the cat nematode Toxocara cati.Citation241 Ocular involvement typically presents in the form of retinal granuloma in the periphery or posterior pole, but chronic endophthalmitis can also occur.Citation241,Citation242 A few cases of optic neuropathy in the form of papillitis, retrobulbar optic neuritis, or neuroretinitis have been reported in serologically proven toxocariasis.Citation243–Citation247 Optic disc granuloma has been reported to occur in 6%–19% of cases.Citation248,Citation249 It appears as a yellowish lesion overlying the optic nerve with associated vitritis. Diagnosis of toxocariasis relies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay testing, and Goldmann-Witmer coefficient analysis applied to an aqueous humor or vitreous sample may help to establish the diagnosis. Treatment of toxocariasis-associated optic neuropathy involves use of periocular and systemic corticosteroids.Citation245 The role of antihelminthic therapy is still controversial.

Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis

Diffuse unilateral subacute neuroretinitis is an infectious ocular disease caused by an unidentified motile nematode capable of infiltrating the subretinal space, causing inflammation and retinal degeneration leading to profound vision loss.Citation250 Optic disc involvement may be seen in the early stage of the disease, with optic disc edema associated with evanescent, multifocal, yellow-white chorioretinal lesions.Citation250,Citation251 The late stage is characterized by profound visual loss, with optic disc atrophy, retinal vessel narrowing, and focal or diffuse retinal pigment epithelium degeneration.Citation250,Citation251 Treatment options include laser therapy when the nematode is visible and chemotherapy with anthelmintic drugs, such as mebendazole, thiabendazole, or albendazole when a worm cannot be visualized.Citation252 Treatment with corticosteroids has shown transient suppression of the inflammation without altering the final outcome of the disease.

Other parasitic infections

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis, also named river blindness or Robles disease, is a parasitic disease caused by the microfilariae Onchocerca volvulus.Citation253 Ocular involvement includes punctate keratitis, corneal opacity, anterior uveitis, and chorioretinal changes, with early disruption of the retinal pigment epithelium and focal areas of atrophy. Later, severe chorioretinal atrophy occurs predominantly in the posterior pole with sheathing of the retinal vessels and optic disc atrophy.Citation253 Diagnosis of onchocerciasis is made by extraction of microfilariae or adult worms from skin or subcutaneous nodules by biopsy or by identification of live microfilariae in the aqueous humor. The disease is treated with ivermectin, given in a single oral dose of 150 μg/kg.Citation253

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease caused by protists of the genus Plasmodium. Malaria is widespread in tropical regions around the equator, including much of sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and the Americas, and is uncommonly seen in developed countries. Ocular involvement in malaria may include retinal hemorrhages and edema, papilledema, disc pallor, vitreous hemorrhage, and cortical blindness.Citation254 Optic neuritis is a rare presentation of the disease, and its diagnosis is difficult.Citation255–Citation257 The pathogenesis of retrobulbar neuritis is still unknown. It is thought to be possibly the result of tissue hypoxia leading to damage of the optic nerve fibers causing loss of vision. The treatment of optic neuritis due to malaria is not clearly established. Improvement of visual acuity has been reported after malarial treatment associated with corticosteroids.Citation256

Angiostrongyliasis

Angiostrongylus cantonensis is a rare parasitic infection that results in eosinophilic meningitis. The human may be infected by eating raw freshwater snails or other paratenic hosts.Citation258 Ocular angiostrongyliasis is a very rare condition, and may include uveitis (with worms in the anterior chamber or in the vitreous), macular edema, retinal edema, necrotic retinitis, panophthalmitis, papilledema, and optic nerve compression.Citation258 Optic neuritis is very rare, and sporadic cases have been reported.Citation258–Citation262 Optic neuritis caused by A. cantonensis may be treated by surgical removal of the parasites or laser-mediated killing of living worms.Citation258 In addition, oral administration of steroids may improve visual acuity by reducing intraocular inflammation.Citation258 Anthelmintics, such as albendazole, are not recommended because dead parasites may cause serious intraocular inflammation.Citation258 The prognosis for optic neuritis in this condition is not favorable, and only slight improvement of visual acuity occurred after treatment in most cases.Citation258

Echinococcosis

Echinococcosis or hydatid disease is a zoonosis caused by the larval stage of the cestode, genus Echinococcus. Orbital involvement is rare, and the most common symptoms in orbital hydatid cyst are slowly progressive unilateral proptosis, with or without pain, visual deterioration with or without optic disc edema, periorbital pain, headache, and disturbance in ocular mobility.Citation263–Citation265 Ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging are diagnostic imaging techniques. The condition may be treated with albendazole or surgical removal of cysts.Citation263–Citation265

Fungal optic neuropathies

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common cause of fungal optic neuropathy, and is related to the acquired immune deficiency syndrome epidemic. Optic neuritis occurs commonly after cryptococcal meningitis and may be either unilateral or bilateral.Citation266–Citation270 The optic nerve damage might result from direct invasion of the nerve by the organism, inflammation, ischemia from vasculitis, increased intracranial pressure, or a combination of these factors. A rapid onset of a few hours to a few days is attributed to direct invasion of the optic nerve and its inflammation. A retrobulbar optic neuropathy can also occur.Citation270 Commonly, patients are already being treated with amphotericin B and/or fluconazole for cryptococcal meningitis and an increase of the dose can be effective in helping to control the optic nerve involvement. Amphotericin B may be given intravitreally and/or intravenously. A slow onset of visual impairment over a few weeks to a few months was attributed to increased intracranial pressure. Antimicrobial treatment may not be effective in such a situation and optic nerve sheath fenestration may be recommended.Citation271

Candidiasis

Candida species are the most common fungal organisms causing endogenous endophthalmitis in immunocompromised patients. Ocular involvement may include anterior uveitis with multiple, bilateral, white, well circumscribed foci of chorioretinitis.Citation272,Citation273 The chorioretinal lesions may be associated with optic disc edema, vasculitis, retinal hemorrhages, and vitreous exudates with a “string-of-pearls” appearance.Citation272,Citation273 Diagnosis is based on context and clinical findings and confirmed by positive results on blood or vitreous cultures and/or PCR. Treatment relies on systemic and/or intravitreal antifungal agents (amphotericin B, fluconazole, and voriconazole).

Histoplasmosis

Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) is a multifocal chorioretinitis presumed to be caused by infection with Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus with both yeast and filamentous forms early in life. Diagnosis of POHS is based on the clinical triad of multiple white, atrophic choroidal scars (histo spots), peripapillary pigment changes, and a maculopathy caused by choroidal neovascularization in the absence of anterior chamber or vitreous inflammation. Optic nerve involvement in POHS is characterized by a ring of peripapillary atrophy with a narrow inner pigment zone adjacent to the disc edge and a white depigmented zone away from the optic disc.Citation274

Aspergillosis

Aspergillus fumigatus is a ubiquitous and saprophytic agent that becomes pathogenic in case of hypoxic area, which can explain its higher incidence in the paranasal sinuses in immunocompromised patients. A few cases of optic neuritis in the setting of aspergillosis have been reported.Citation275–Citation279 The clinical presentation can mimic nonspecific optic neuritis, with a possible good response to corticosteroid therapy.Citation278 Several cases of orbital apex syndrome secondary to aspergillus are reported.Citation279 The pattern of visual field defect depends on anatomical extension of the infection. The diagnosis of ocular aspergillosis might be difficult especially in the early stage. Repeated radiological examination and orbital biopsy may be required in the event of a high level of clinical suspicion. Management of aspergillosis involves prompt surgical excision of the involved tissue with sinus exenteration. Intensive antifungal therapy with amphotericin B is also recommended.

Mucormycosis

Mucormycosis is an opportunistic fungal infection caused by Mucorales (Mucor, Rhizopus, Absidia, and Cunninghamella).Citation280 It is a potentially lethal infection that generally affects immunocompromised patients; however, cases in immunocompetent and diabetic patients have been reported. Rhino–orbito–cerebral mucormycosis presents with nonspecific complaints such as headache, low-grade fever, facial swelling, sinusitis, proptosis, conjunctival injection, and restricted extraocular motility. Optic nerve involvement in mucormycosis includes optic nerve infarction and necrosis that may result from invasion of the blood vessel walls by the organisms, leading to occlusion or thrombosis of the optic nerve sheath, blood vessels, or ophthalmic artery.Citation281–Citation283 Direct optic nerve infection by mucormycosis may also occur. Treatment involves aggressive surgical debridement of all involved tissues including exenteration of involved orbits, with prolonged administration of amphotericin B.

Post-vaccination optic neuropathies

Optic nerve involvement has been described in association with vaccination against various bacterial and virus infections. These include tuberculosis (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination), influenza virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis A virus, yellow fever, measles/rubella vaccines, mumps, diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, rabies virus, and variola virus.Citation284–Citation301

Post-vaccination optic neuritis is a rare event that may occur hours to weeks after vaccination. The presumed pathogenesis of this event is an immune-mediated mechanism. Most cases are bilateral, and include anterior or retrobulbar optic neuritis and neuroretinitis. The overall prognosis is good, and corticosteroids may hasten visual recovery.Citation284–Citation301

Data from a case-control study show no increased risk of multiple sclerosis or optic neuritis following vaccination against hepatitis B, influenza, tetanus, measles, or rubella.Citation302 Nevertheless, a possible causal relationship between vaccination against virus infection and development of optic neuritis cannot be completely excluded.Citation303

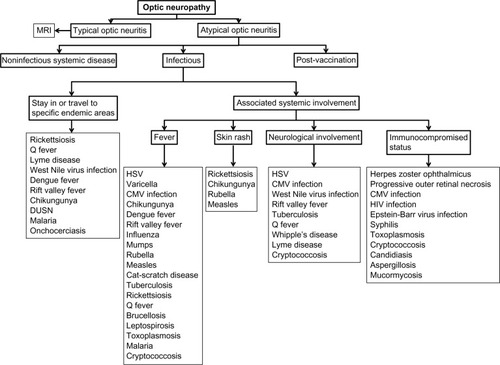

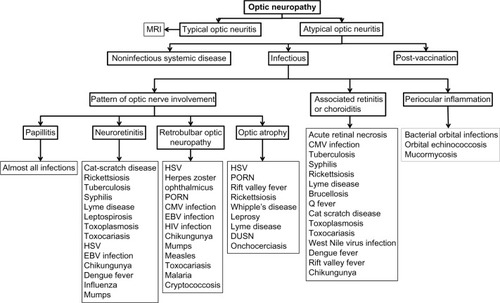

Diagnostic approach to infectious optic neuropathy

Optic neuritis is the most common optic neuropathy, which usually affects young adults. It typically presents as an acute, unilateral inflammatory demyelinating disorder of the optic nerve that can be associated with multiple sclerosis. A gradual recovery of visual acuity with time is characteristic of optic neuritis, and the work-up should be limited to cerebromedullary magnetic resonance imaging. Atypical optic neuritis may be characterized by bilateral involvement, significant ocular inflammatory reaction, atypical clinical course, and associated systemic involvement. Atypical optic neuropathy may be associated with a wide variety of infectious () and noninfectious disorders. Appropriate clinical diagnosis and laboratory work-up of a patient with infectious optic neuropathy are based on epidemiological data, history, the patient’s immunological status, systemic symptoms and signs, and associated inflammatory involvement that may involve the adnexa, anterior segment, vitreous, retina, and choroid, as well as neuro–ophthalmological involvement ( and ).

Figure 7 Practical approach to infectious optic neuropathies according to epidemiologic data and associated systemic involvement.

Figure 8 Practical approach to infectious optic neuropathies according to associated ocular findings.

Table 1 Summary of findings in main infectious optic neuropathies

Evaluation of patients with suspected infectious optic neuropathy may include a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, serological testing, blood cultures, PCR, or antibody assessment in aqueous humor, vitreous, serum, or cerebrospinal fluid, a tuberculin skin test and/or quantiferon, tomodensitometry, and magnetic resonance imaging.

Conclusion

A wide variety of viral, bacterial, parasitic, and fungal agents can cause optic neuropathy, with variable clinical features. Proper clinical diagnosis of any specific infectious condition is based on epidemiological data, history, systemic symptoms and signs, and the pattern of optic nerve involvement and associated ocular findings, which can be confirmed by laboratory testing. Most infectious agents can be effectively treated with specific anti-infectious drugs with or without associated corticosteroid therapy, but visual recovery is highly variable.

Author contributions

MK, RK, NA, IK, AM, HZ, and SZ made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. MK and RK were responsible for drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. MK, RK, NA, IK, AM, HZ, and SZ gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education and Research of Tunisia.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GolnikKCInfectious optic neuropathySemin Ophthalmol2002171111715513450

- BhattiMTOptic neuropathy from viruses and spirochetesInt Ophthalmol Clin2007474376618049280

- VaphiadesMGolnikKCOptic neuropathy from bacteriaInt Ophthalmol Clin2007474253618049279

- LauCHMissottenTSalzmannJLightmanSLAcute retinal necrosis features, management, and outcomesOphthalmology2007114475676217184841

- WitmerMTPavanPRFourakerBDLevy-ClarkeGAAcute retinal necrosis associated optic neuropathyActa Ophthalmol201189759960720645925

- SergottRCBelmontJBSavinoPJFischerDHBosleyTMSchatzNJOptic nerve involvement in the acute retinal necrosis syndromeArch Ophthalmol19851038116011624026646

- FrancisPJJacksonHStanfordMRGrahamEMInflammatory optic neuropathy as the presenting feature of herpes simplex acute retinal necrosisBr J Ophthalmol2003874512514

- KangSWKimSKOptic neuropathy and central retinal vascular obstruction as initial manifestations of acute retinal necrosisJpn J Ophthalmol200145442542811485778

- KojimaMKimuraHYodoiYMatsunagaNOguraYPreceding of optic nerve involvement in acute retinal necrosisRetina200424229729915097893

- StergiouPKKonstantinouIMKaragianniTNKavakiDPrintzaNGOptic neuritis caused by varicella infection in an immunocompetent childPediatr Neurol200737213813917675031

- GalbusseraATagliabueEFrigoMApalePFerrareseCAppollonioIIsolated bilateral anterior optic neuritis following chickenpox in an immunocompetent adultNeurol Sci200627427828016998733

- AzevedoARSimõesRSilvaFOptic neuritis in an adult patient with chickenpoxCase Rep Ophthalmol Med2012201237158423320222

- LeeCCVenketasubramanianNLamMSOptic neuritis: a rare complication of primary varicella infectionClin Infect Dis19972435155169114212

- MillerDHKayRSchonFMcDonaldWIHaasLFHughesRAOptic neuritis following chickenpox in adultsJ Neurol198623331821843723155

- PurvinVHrisomalosNDunnDVaricella optic neuritisNeurology19883855015033347360

- TappeinerCAebiCGarwegJGRetinitis and optic neuritis in a child with chickenpox: case report and review of literaturePediatr Infect Dis J201029121150115220622712

- de Mello VitorBFoureauxECPortoFBHerpes zoster optic neuritisInt Ophthalmol201131323323621626168

- WangAGLiuJHHsuWMLeeAFYenMYOptic neuritis in herpes zoster ophthalmicusJpn J Ophthalmol200044555055411033135

- KotheACFlanaganJTrevinoRCTrue posterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicusOptom Vis Sci199067118458492250894

- HongSMYangYSA case of optic neuritis complicating herpes zoster ophthalmicus in a childKorean J Ophthalmol201024212613020379464

- PakravanMAhmadiehHKaharkaboudiARPosterior ischemic optic neuropathy following herpes zoster ophthalmicusJ Ophthalmic Vis Res200941596223056674

- SalazarRRussmanANNagelMAVaricella zoster virus ischemic optic neuropathy and subclinical temporal artery involvementArch Neurol201168451752021482932

- NagelMARussmanANFeitHVZV ischemic optic neuropathy and subclinical temporal artery infection without rashNeurology201380222022223255829

- EngstromREJrHollandGNMargolisTPThe progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome. A variant of necrotizing herpetic retinopathy in patients with AIDSOphthalmology19941019148815028090452

- NakamotoBKDorotheoEUBiousseVTangRASchiffmanJSNewmanNJProgressive outer retinal necrosis presenting with isolated optic neuropathyNeurology200463122423243515623719

- PatelAOlavarriaEOptic neuritis preceding progressive outer retinal necrosis in an immunocompromised patient after allogeneic stem cell transplantationAnn Hematol201392101427142923404584

- MansourAMCytomegalovirus optic neuritisCurr Opin Ophthalmol1997835558

- MansorAMLiHKCytomegalovirus optic neuritis: characteristics, therapy and survivalOphthalmologica199520952602668570149

- PatelSSRutzenARMarxJLThachABChongLPRaoNACytomegalovirus papillitis in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: visual prognosis of patients treated with ganciclovir and/or foscarnetOphthalmology19961039147614828841309

- GrossJGSadunAAWileyCAFreemanWRSevere visual loss related to isolated peripapillary retinal and optic nerve head cytomegalovirus infectionAm J Ophthalmol198910866916982556923

- IoannidisASBaconJFrithPJuxtapapillary cytomegalovirus retinitis with optic neuritisJ Neuroophthalmol200828212813018562846

- MunteanuGMunteanuMCytomegalovirus retinitis and optic neuropathy in a case of an infectious HIV syndromeOftalmologia19994947881 Romanian11021290

- CackettPWeirCRMcFadzeanRSeatonRAOptic neuropathy without retinopathy in AIDS and cytomegalovirus infectionJ Neuroophthalmol2004241949515206448

- ParkKHBangJHParkWBRetrobulbar optic neuritis and meningoencephalitis following progressive outer retinal necrosis due to CMV in a patient with AIDSInfection200836547547918574556

- ZhengXHuangYWangZYanHPanSWangHPresumed cytomegalovirus-associated retrobulbar optic neuritis in a patient after allogeneic stem cell transplantationTranspl Infect Dis201214217717922093546

- BaglivoELeuenbergerPMKrauseKHPresumed bilateral cytomegalovirus-induced optic neuropathy in an immunocompetent person. A case reportJ Neuroophthalmol199616114178963414

- De SilvaSRChohanGJonesDHuMCytomegalovirus papillitis in an immunocompetent patientJ Neuroophthalmol200828212612718562845

- ChangPYHamamRGiuliariGPFosterCSCytomegalovirus panuveitis associated with papillitis in an immunocompetent patientCan J Ophthalmol2012474e12e1322883854

- AndersonMDKennedyCALewisAWChristensenGRRetrobulbar neuritis complicating acute Epstein-Barr virus infectionClin Infect Dis19941857998018075274

- StraussbergRAmirJCohenHASavirHVarsanoIEpstein-Barr virus infection associated with encephalitis and optic neuritisJ Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus19933042622638410579

- Santos-BuesoESáenz-FrancésFMéndez-HernándezCPapillitis due to Epstein-Barr virus infection in an adult patientArch Soc Esp Oftalmol2014896245249 Spanish24269432

- PurvinVHerrGJDe MyerWChiasmal neuritis as a complication of Epstein-Barr virus infectionArch Neurol19884544584602833208

- BeiranIKrasnitzIZimhoni-EibsitzMGelfandYAMillerBPaediatric chiasmal neuritis – typical of post-Epstein-Barr virus infection?Acta Ophthalmol Scand200078222622710794264

- GoldsmithPJonesREOzuzuGERichardsonJOngELOptic neuropathy as the presenting feature of HIV infection: recovery of vision with highly active antiretroviral therapyBr J Ophthalmol200084555155310847713

- NewmanNJLessellSBilateral optic neuropathies with remission in two HIV-positive menJ Clin Neuroophthalmol1992121151532592

- QuicenoJICapparelliESadunAAVisual dysfunction without retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndromeAm J Ophthalmol199211318131728151

- GautierDRabierVJalletGMileaDVisual loss related to macular subretinal fluid and cystoid macular edema in HIV-related optic neuropathyInt Ophthalmol201232440540822581321

- LarsenMToftPBBernhardPHerningMBilateral optic neuritis in acute human immunodeficiency virus infectionActa Ophthalmol Scand19987667377389881565

- Le CorreARobinAMaaloufTAngioiKRecurrent unilateral optic neuropathy associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)J Fr Ophtalmol2012354272276 French22421033

- BabuKMurthyKRRajagopalanNSatishBVision recovery in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with optic neuropathy treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy: a case seriesIndian J Ophthalmol200957431531819574705

- MahadevanASatishchandraPPrachetKKOptic nerve axonal pathology is related to abnormal visual evoked responses in AIDSActa Neuropathol2006112446146916788820

- SadunAAPeposeJSMadiganMCLaycockKATenhulaWNFreemanWRAIDS-related optic neuropathy: a histological, virological and ultrastructural studyGraefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol199523373873987557502

- GargSJampolLMSystemic and intraocular manifestations of West Nile virus infectionSurv Ophthalmol200550131315621074

- KhairallahMBen YahiaSLadjimiAChorioretinal involvement in patients with West Nile virus infectionOphthalmology2004111112065207015522373

- ChanCKLimstromSATarasewiczDGLinSGOcular features of West Nile virus infection in North America: a study of 14 eyesOphthalmology200611391539154616860390

- KhairallahMKahlounROcular manifestations of emerging infectious diseasesCurr Opin Ophthalmol201324657458024030241

- HershbergerVSAugsburgerJJHutchinsRKMillerSAHorwitzJABergmannMChorioretinal lesions in nonfatal cases of West Nile virus infectionOphthalmology200311091732173613129870

- AnningerWVLomeoMDDingleJEpsteinADLubowMWest Nile virus-associated optic neuritis and chorioretinitisAm J Ophthalmol200313661183118514644244

- VaispapirVBlumASobohSAshkenaziHWest Nile virus meningoencephalitis with optic neuritisArch Intern Med20021625606607

- AnningerWLubowMVisual loss with West Nile virus infection: a wider spectrum of a “new” diseaseClin Infect Dis2004387e55e5615034847

- GiladRLamplYSadehMPaulMDanMOptic neuritis complicating West Nile virus meningitis in a young adultInfection2003311555612590335

- SivakumarRRPrajnaLAryaLKMolecular diagnosis and ocular imaging of West Nile virus retinitis and neuroretinitisOphthalmology201312091820182623642374

- MahendradasPAvadhaniKShettyRChikungunya and the eye: a reviewJ Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect2013313523514031

- LalithaPRathinamSBanushreeKMaheshkumarSVijayakumarRSathePOcular involvement associated with an epidemic outbreak of Chikungunya virus infectionAm J Ophthalmol2007144455255617692276

- MahendradasPRangannaSKShettyROcular manifestations associated with chikungunyaOphthalmology2008115228729117631967

- MittalAMittalSBharatiMJRamakrishnanRSaravananSSathePSOptic neuritis associated with chikungunya virus infection in South IndiaArch Ophthalmol2007125101381138617923547

- RoseNAnoopTMJohnAPJabbarPKGeorgeKCAcute optic neuritis following infection with chikungunya virus in southern rural IndiaInt J Infect Dis2011152e147e15021131222

- MaheshGGiridharAShedbeleAKumarRSaikumarSJA case of bilateral presumed chikungunya neuroretinitisIndian J Ophthalmol200957214815019237792

- NairAGBiswasJBhendeMPA case of bilateral Chikungunya neuroretinitisJ Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect201221394021881835

- BeralLMerleHDavidTOcular complications of Dengue feverOphthalmology200811561100e118519071

- NgAWTeohSCDengue eye diseaseSurv Ophthalmol201560210611425223497

- SanjaySWagleAMAu EongKGDengue optic neuropathyOphthalmology20091161170

- HaritoglouCDotseSDRudolphGStephanCMThurauSRKlaussVA tourist with dengue fever and visual lossLancet20023609339107012383989

- MohindraVKKumariAUnilateral optic neuritis associated with dengue feverDelhi J Ophthalmol201323293294

- PreechawatPPoonyathalangABilateral optic neuritis after dengue viral infectionJ Neuroophthalmol2005251515215756136

- SanjaySWagleAMAu EongKGOptic neuropathy associated with dengue feverEye (Lond)200822572272418344950

- de Amorim GarciaCAGomesAHde OliveiraAGBilateral stellar neuroretinitis in a patient with dengue feverEye (Lond)200620121382138316410810

- Miranda de SousaAPuccioni-SohlerMDias BorgesAFernandes AdornoLPapais AlvarengaMPapais AlvarengaRMPost-dengue neuromyelitis optica: case report of a Japanese-descendent Brazilian childJ Infect Chemother200612639639817235647

- Al-HazmiAAl-RajhiAAAbboudEBOcular complications of Rift Valley fever outbreak in Saudi ArabiaOphthalmology2005112231331815691569

- SiamALMeeganJMGharbawiKFRift Valley fever ocular manifestations: observations during the 1977 epidemic in EgyptBr J Ophthalmol19806453663747192158

- JanuschowskiKWilhelmHOptic neuropathy with concentric visual field constriction following life-threatening H1N1-infectionKlin Monbl Augenheilkd201022711860861 Germany21077018

- VianelloFAOsnaghiSLaiciniEAOptic neuritis associated with influenza B virus meningoencephalitisJ Clin Virol201461346346525308101

- LaiCCChangYSLiMLChangCMHuangFCTsengSHAcute anterior uveitis and optic neuritis as ocular complications of influenza A infection in an 11-year-old boyJ Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus201148 Onlinee30e3321732577

- MansourDEEl-ShazlyAAElawamryAIIsmailATComparison of ocular findings in patients with H1N1 influenza infection versus patients receiving influenza vaccine during a pandemicOphthalmic Res201248313413822572924

- NakamuraYIkedaKYoshiiYInfluenza-associated monophasic neuromyelitis opticaIntern Med201150151605160921804290

- NorthDPOcular complications of mumpsBr J Ophthalmol19533729910113032360

- KhubchandaniRRaneTAgarwalPNabiFPatelPShettyAKBilateral neuroretinitis associated with mumpsArch Neurol200259101633163612374502

- FosterRELowderCYMeislerDMKosmorskyGSBaetz-GreenwaltBMumps neuroretinitis in an adolescentAm J Ophthalmol1990110191932368830

- SugitaKAndoMMinamitaniKMiyamotoHNiimiHMagnetic resonance imaging in a case of mumps postinfectious encephalitis with asymptomatic optic neuritisEur J Pediatr1991150117737751959539

- GnananayagamEJAgarwalIPeterJPrashanthPJohnDBilateral retrobulbar neuritis associated with mumpsAnn Trop Paediatr2005251676815814053

- CansuAAyşeSSengülOKivilcimGTuğbaHLBilateral isolated acute optic neuritis in a child after acute rubella infectionJpn J Ophthalmol200549543143316187052

- YoshidaRHiranoYIzumiTFukuyamaYA case of optic neuritis following rubella encephalitisNo To Hattatsu1993255442446 Japanese8398234

- ConnollyJHHutchinsonWMAllenIVCarotid artery thrombosis, encephalitis, myelitis and optic neuritis associated with rubella virus infectionsBrain19759845835941218369

- InokuchiNNishikawaNFujikadoTOptic neuritis and measles infectionNippon Rinsho1997554861864 Japanese

- NakajimaNUedaMYamazakiMTakahashiTKatayamaYOptic neuritis following aseptic meningitis associated with modified measles: a case reportJpn J Infect Dis201366432032223883844

- AzumaMMorimuraYKawaharaSOkadaAABilateral anterior optic neuritis in adult measles infection without encephalomyelitisAm J Ophthalmol2002134576876912429258

- TotanYCekiçOBilateral retrobulbar neuritis following measles in an adultEye (Lond)199913Pt 3A38338410624445

- TomiyasuKIshiyamaMKatoKBilateral retrobulbar optic neuritis, Guillain-Barré syndrome and asymptomatic central white matter lesions following adult measles infectionIntern Med200948537738119252366

- CunninghamETKoehlerJEOcular bartonellosisAm J Ophthalmol2000130334034911020414

- BiancardiALCuriALCat scratch diseaseOcul Immunol Inflamm201422214815424107122

- CarithersHACat-scratch disease. An overview based on a study of 1,200 patientsAm J Dis Child198513911112411334061408

- BarSSegalMShapiraRSavirHNeuroretinitis associated with cat scratch diseaseAm J Ophthalmol199011067037052248340

- OrmerodLDSkolnickKAMenoskyMMPavanPRPonDMRetinal and choroidal manifestations of cat-scratch diseaseOphthalmology19981056102410319627652

- ReedJBScalesDKWongMTLattuadaCPJrDolanMJSchwabIRBartonella henselae neuroretinitis in cat scratch disease. Diagnosis, management, and sequelaeOphthalmology199810534594669499776

- ChiSLStinnettSEggenbergerEClinical characteristics in 53 patients with cat scratch optic neuropathyOphthalmology2012119118318721959368

- WadeNKLeviLJonesMRBhisitkulRFineLCunninghamETJrOptic disk edema associated with peripapillary serous retinal detachment: an early sign of systemic Bartonella henselae infectionAm J Ophthalmol2000130332733411020412

- CunninghamETJrMcDonaldHRSchatzHJohnsonRNAiEGrandMGInflammatory mass of the optic nerve head associated with systemic Bartonella henselae infectionArch Ophthalmol199711512159615979400801

- LombardoJCat-scratch neuroretinitisJ Am Optom Assoc199970852553010506816

- SolleyWAMartinDFNewmanNJCat scratch disease: posterior segment manifestationsOphthalmology199910681546155310442903

- CuriALMachadoDHeringerGCat-scratch disease: ocular manifestations and visual outcomeInt Ophthalmol201030555355820668914

- OrmerodLDDaileyJPOcular manifestations of cat-scratch diseaseCurr Opin Ophthalmol199910320921610537781

- DaltonMJRobinsonLECooperJUse of Bartonella antigens for serologic diagnosis of cat-scratch disease at a national referral centerArch Intern Med199515515167016767542443

- BarkaNEHadfieldTPatnaikMSchwartzmanWAPeterJBEIA for detection of Rochalimaea henselae reactive IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies in patients with suspected cat-scratch disease (letter)J Infect Dis1993167615038501350

- LabalettePBermondDDedesVSavageCCat-scratch disease neuroretinitis diagnosed by a polymerase chain reaction approachAm J Ophthalmol2001132457557611589885

- MargilethAMAntibiotic therapy for cat-scratch disease: clinical study of therapeutic outcome in 268 patients and a review of the literaturePediatr Infect Dis J19921164744781608685

- RolainJMBrouquiPKoehlerJERecommendations for treatment of human infections caused by Bartonella speciesAntimicrob Agents Chemother20044861921193315155180

- KalogeropoulosCKoumpoulisIMentisAPappaCZafeiropoulosPAspiotisMBartonella and intraocular inflammation: a series of cases and review of literatureClin Ophthalmol2011581782921750616

- MargilethAMCat scratch diseaseAdv Pediatr Infect Dis199381218216999

- GuptaVGuptaARaoNAIntraocular tuberculosis – an updateSurv Ophthalmol200752656158718029267

- GuptaVShoughySSMahajanSClinics of ocular tuberculosisOcul Immunol Inflamm2015231142425615807

- DavisEJRathinamSROkadaAAClinical spectrum of tuberculous optic neuropathyJ Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect20122418318922614321

- GuptaAGuptaVPandavSSGuptaAPosterior scleritis associated with systemic tuberculosisIndian J Ophthalmol200351434734914750624

- AmitavaAKAlarmSHussainRNeuro-ophthalmic features in pediatric tubercular meningoencephalitisJ Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus200138422923411495311

- PoonWSAhujaALiAKOptochiasmatic tuberculoma causing progressive visual failure: when has medical treatment failed?Postgrad Med J1993698081471498506198

- DasJCSinghKSharmaPSinglaRTuberculous osteomyelitis and optic neuritisOphthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging200334540941214509469

- StechschulteSUKimRYCunninghamETJrTuberculous neuroretinitisJ Neuroophthalmol199919320120410494950

- PapadiaMHerbortCPUnilateral papillitis, the tip of the iceberg of bilateral ICGA-detected tuberculous choroiditisOcul Immunol Inflamm201119212412621428752

- HughesEHPetrushkinHSibtainNAStanfordMRPlantGTGrahamEMTuberculous orbital apex syndromesBr J Ophthalmol200892111511151718614572

- SchleraitzauerDAHodgesFJBaganMTuberculoma of the left optic nerve and chiasmArch Ophthalmol197185175784321752

- IraciGGiordanoRGerosaMPardatscherKTomazzoliLTuberculoma of the anterior visual pathwaysJ Neurosurg19805211291336243157

- ScottRMSonntagVKWilcoxLMAdelmanLSRockelTHVisual loss from optochiasmatic arachnoiditis after tuberculous meningitisJ Neurosurg1977464524526845636

- Caire EstévezJPGonzález-Ocampo DortaSSanz SolanaPPapilledema secondary to tuberculous meningitis in a patient with type 1 diabetes mellitusArch Soc Esp Oftalmol20138810403406 Spanish24060305

- AngMHtoonHMCheeSPDiagnosis of tuberculous uveitis: clinical application of an interferon-gamma release assayOphthalmology200911671391139619576501

- ChaoJRKhuranaRNFawziAAReddyHSRaoNASyphilis: reemergence of an old adversaryOphthalmology2006113112074207916935333

- PeelingRWHookEWIIIThe pathogenesis of syphilis: the Great Mimicker, revisitedJ Pathol2006208222423216362988

- BrowningDJPosterior segment manifestations of active ocular syphilis, their response to a neurosyphilis regimen of penicillin therapy, and the influence of human immunodeficiency virus status on responseOphthalmology2000107112015202311054325

- SmithGTGoldmeierDMigdalCNeurosyphilis with optic neuritis: an updatePostgrad Med J200682963363916397078

- MeehanKRodmanJOcular perineuritis secondary to neurosyphilisOptom Vis Sci20108710E790E79620802364

- SacksJGOsherRHElconinHProgressive visual loss in syphilitic optic atrophyJ Clin Neuroophthalmol198331586222079

- ArrugaJValentinesJMauriFRocaGSalomRRufiGNeuroretinitis in acquired syphilisOphthalmology19859222622703982805

- SmithJLByrneSFCambronCRSyphiloma/gumma of the optic nerve and human immunodeficiency virus seropositivityJ Clin Neuroophthalmol19901031751842144534

- MansbergerSLMacKenziePJFalardeauJOptic disc cupping associated with neurosyphilisJ Glaucoma2013222808321946555

- GaudioPAUpdate on ocular syphilisCurr Opin Ophthalmol200617656256617065926