Abstract

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) refers to a spectrum of conjunctival and corneal epithelial tumors including dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma. In this article, we discuss the current perspectives of OSSN associated with HIV infection, focusing mainly on the epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of these tumors in patients with HIV. Upsurge in the incidence of OSSN with the HIV pandemic most severely affected sub-Saharan Africa, due to associated risk factors, such as human papilloma virus and solar ultraviolet exposure. OSSN has been reported as the first presenting sign of HIV/AIDS in 26%–86% cases, and seropositivity is noted in 38%–92% OSSN patients. Mean age at presentation of OSSN has dropped to the third to fourth decade in HIV-positive patients in developing countries. HIV-infected patients reveal large aggressive tumors, higher-grade malignancy, higher incidence of corneal, scleral, and orbital invasion, advanced-stage T4 tumors, higher need for extended enucleation/exenteration, and increased risk of tumor recurrence. Current management of OSSN in HIV-positive individuals is based on standard treatment guidelines described for OSSN in the general population, as there is little information available about various treatment modalities or their outcomes in patients with HIV. OSSN can occur at any time in the disease course of HIV/AIDS, and no significant trend has been discovered between CD4 count and grade of OSSN. Furthermore, the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on OSSN is controversial. The current recommendation is to conduct HIV screening in all cases presenting with OSSN to rule out undiagnosed HIV infection. Patient counseling is crucial, with emphasis on regular follow-up to address high recurrence rates and early presentation to an ophthalmologist for of any symptoms in the unaffected eye. Effective evidence-based interventions are needed to allow early diagnosis and treatment, as well as prevention of the disease.

Introduction

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) refers to a spectrum of conjunctival and corneal epithelial tumors including dysplasia, carcinoma-in-situ and invasive carcinoma (squamous cell carcinoma) which may or may not be associated with intraocular or orbital extension.Citation1,Citation2 OS malignancies, such as OSSN, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, are notably expressed in people with HIV/AIDS, among which OSSN is known to occur in 4%–8% of patients.Citation3,Citation4

Although there has been a decline in the incidence of HIV in recent years, there has been a surge in the incidence of OSSN in the population with HIV, due to its linear relationship with the HIV pandemic in the last few decades.Citation5–Citation18 This dramatic rise in HIV infection during the pandemic has resulted in gradual drift in the age of presentation, clinical course, and management of patients with OSSN.Citation5,Citation19 HIV not only increases risk of OSSN but also influences the severity of disease and its prognosis.

Incidence and risk of OSSN with HIV infection

According to a World Health Organization report, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS worldwide was 36.7 million at the end of 2016. While the burden of the epidemic continues to vary substantially between countries and regions, sub-Saharan Africa remains most severely affected and accounts for almost two-thirds of the total new HIV infections globally.Citation20 The geographical distribution of OSSN all over the world is also affected by the HIV pandemic.Citation10,Citation11,Citation21

HIV infection is recognized as a risk factor for the development of OSSN in various studies from sub-Saharan Africa.Citation13,Citation22–Citation26 The Kampala Cancer Registry in Uganda recorded a sixfold increase in the incidence of conjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma: from an average of six per million per year in 1988 to 35 per million per year in 1992.Citation10 Various studies have observed a three- to 30-fold increased risk of OSSN developing in HIV infected individuals.Citation7,Citation27–Citation29

Although a strong association between HIV and OSSN has been established by numerous studies, some patients with OSSN are not aware of their HIV status until HIV screening confirms the seropositivity. In studies from sub-Saharan Africa where HIV screening was done in all patients with OSSN, seropositivity was detected in 49%–92% cases, indicating a high association between OSSN and HIV status in African countries.Citation5,Citation7–Citation12,Citation14,Citation15,Citation30 In Africa, OSSN has been reported as the first presenting sign of HIV/AIDS in 50%–86% cases.Citation8–Citation12,Citation31 This trend is now well documented in many African countries, and with increasing migration it is appreciated in other developing and developed countries as well. In studies from India by Kaliki et al and Kamal et al, HIV positivity was noticed in 38%–41% of diagnosed OSSN patients, of which 70% were unaware of their status prior to screening.Citation32,Citation33 In 26% of patients, OSSN was the first and only evident manifestation of HIV.Citation32

There are limited data from the US, which shows a higher incidence of OSSN among people with HIV than the general population. Guech-Ongey et al noted a significant 12-fold risk of OSSN in people with HIV/AIDS.Citation6 Frish et al also noticed similar results while studying relative risk of human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated cancers in HIV-infected individuals.Citation34 Goedert and Coté observed that the risk of OSSN among people with HIV changed with duration from diagnosis of AIDS, with an exponential rise in squamous-cell carcinoma in HIV patients 2 years after the diagnosis of AIDS.Citation35 In a study by Karp et al among younger patients (<50 years) with OSSN, 50% were HIV-positive, 33% of whom were unaware of their HIV infection.Citation16 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies, it was revealed that HIV infection augmented the risk of OSSN, with an overall relative risk estimate of 8.06 (95% CI 5.29–12.3).Citation18

Epidemiology

Mean age at presentation

The epidemiology of OSSN has changed over the last few decades, especially in developing countries. Although once considered an uncommon tumor occurring in the elderly,Citation36 it is becoming more common and more likely to affect young populations.Citation12,Citation14,Citation32,Citation37–Citation40 It has been observed that the mean age at presentation of OSSN has dropped to the third to fourth decade in HIV-positive patients from the sixth decade in HIV-negative patients.Citation7,Citation11,Citation12,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42 The mean age at presentation of OSSN in people with HIV/AIDS in various studies is approximately 35–41 years.Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation12,Citation14,Citation15,Citation32,Citation39–Citation41 In developed countries, patients with OSSN have a different disease profile and continue to present in elderly in both the general populationCitation36,Citation38,Citation43,Citation44 and in HIV-infected individuals.Citation6

Sex predisposition

Studies from Africa have reported a striking feature of either a female preponderanceCitation7,Citation10,Citation14,Citation39,Citation41,Citation45 or no sex differenceCitation3 in HIV-positive OSSN patients, while others have noted dominance by elderly males.Citation8,Citation15,Citation45 This predilection may result from the presence of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, high HPV exposure, and solar radiation in the region.Citation45 In developed countries, males are more commonly affected than females in the general population,Citation36,Citation38,Citation43,Citation44 as well as in people with HIV.Citation6 Studies from Australia, Britain, and San Francisco have found that 70%–80% of patients with OSSN are males,Citation36,Citation38,Citation46 with rare occurrence of HIV seropositivity.

Etiology

The cause of OSSN is multifactorial, but the precise etiopathogenesis is unknown. HIV,Citation10,Citation11 HPV,Citation11,Citation13,Citation47 and solar ultraviolet exposureCitation14,Citation48 are postulated risk factors for the development of OSSN.Citation6,Citation17 An association between OSSN and cigarette smoking, vitamin A deficiency, and allergic eye disease has also been described. It is suggested that the increase in incidence of OSSN in sub-Saharan Africa is related to the coexistence of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, infection with HPV, and exposure to solar radiation in the region.Citation45,Citation49 The overlap of these factors in parts of the world with rapidly rising incidence of OSSN indicates that they possibly interact with one another. Therefore, it is difficult to describe a single one as the causative factor.Citation50

It is considered that HIV infection causes the breakdown of immunosurveillance of malignant cells as a result of suppression of cell-mediated immunoresponse.Citation51 The relationship between HPV and OSSN is controversial, with variable results about the two types of HPV.Citation52 Studies have established no association between mucosal HPV types and OSSN, while others found an uncertain role of cutaneous HPV type in OSSN.Citation53,Citation54 A systematic review by Carreira et al suggested that only the cutaneous HPV subtypes were associated with an increased risk of OSSN.Citation18 Studies suggest that HPV alone may be a contributing factor to OSSN, but is unlikely to cause it.Citation11,Citation27 Karp et al hypothesized that HIV predisposes to OSSN by creating a “permissive environment” for activation of oncogenic HPV, which subsequently act as a cofactor in the development of neoplasia.Citation16,Citation55 This also explains the increased prevalence of HPV in immunosuppressed individuals with HIV disease.Citation11,Citation56–Citation58

Clinical features

Symptoms

Symptoms in patients with OSSN may range from none at all to severe pain and/or visual loss.Citation1 The most common presentations are a red eye, ocular irritation,Citation46 or appearance of a mass lesion in the eye.Citation14,Citation32 OSSN presents as a slowly growing lesion in the general population,Citation38,Citation59 while it behaves aggressively in HIV-infected individuals in both developingCitation10,Citation16,Citation33 and developed countries.Citation55 It often presents with large and unsightly disfiguring lesions in late disease.Citation45 In HIV-infected individuals, longer duration between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of tumor is noted in a few studies from Africa,Citation7,Citation33,Citation39 with a mean history of 3 months at presentation.Citation28,Citation37 Such longer duration and largeness of the lesion imply that many patients either do not seek medical care early or receive long-term conservative treatment for other ocular conditions due to misdiagnosis.Citation60 Satisfactory training of eye-health care professionals is necessary for active participation to rule out malignancy clinically, to consider incisional biopsy for histopathological confirmation in doubtful cases, and to follow up closely.Citation3

Signs

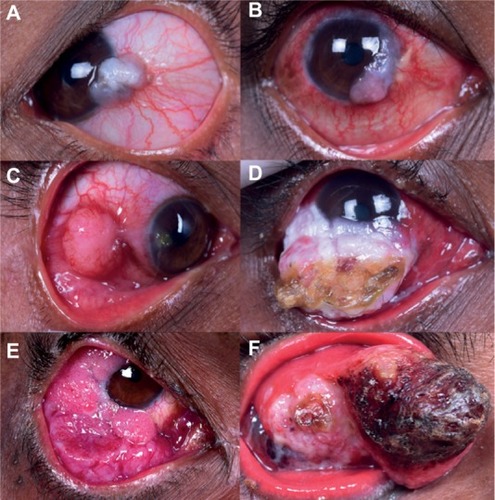

OSSN commonly affects the interpalpebral conjunctiva, and frequently arises from the nasal limbus.Citation1,Citation16 It can present either as a solitary growth or with diffuse involvement of the OS. Solitary tumors can be nodular, noduloulcerative, gelatinous, leukoplakic, placoid, or papillary in morphologyCitation61 (). Makupa et al noted higher incidence of leukoplakia and feeder vessels,Citation7 while Kabra et al mentioned large lesions with fornicial extensionCitation62 at the time of presentation in HIV-infected patients.

Figure 1 Clinical presentation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients.

The majority of cases are unilateral;Citation3 however, 15% of cases present with bilateral involvement, and multifocal lesions are noted in 3% of cases.Citation32 Bilateral presentation can be simultaneous or sequential, as highlighted in a series of four patients in seropositive patients by Masanganise et al.Citation63 Finances and fear of losing the only eye were the possible reasons for delayed follow-up and advanced disease requiring enucleation or orbital exenteration.

Studies from the sub-Saharan region have established that HIV-infected patients have larger tumors, higher-grade malignancy, and increased risk of tumor recurrence.Citation7,Citation12 Kaliki et al found significant differences between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, including larger tumors, higher incidence of corneal, scleral, and orbital invasion, advanced stage T4 American Joint Committee on Cancer tumors, and higher need for extended enucleation/orbital exenteration in HIV-positive cases.Citation32,Citation33 Similar findings of aggressive and invasive OSSN in individuals with HIV were described in a study by Shields et al.Citation55 The invasive nature of the tumor may be correlated with longer duration of symptoms.Citation33

Rarely, this tumor can present as necrotizing scleritis with scleral perforation and prolapse of uveal tissue as a manifestation of intraocular extension.Citation64 Early identification of corneal, scleral invasion, intraocular or orbital extension clinically or with ancillary investigations is crucial. This will reduce morbidity and will result in better anatomical outcomes in terms of globe salvage and cosmesis.Citation65 An unusual case in a seropositive male has been described who presented with widespread metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma after the primary OSSN in the lower palpebral conjunctiva had been misdiagnosed and treated conservatively as chalazion.Citation66 OSSN can often extend to regional lymph nodes, surrounding paranasal sinuses and the brain in HIV-positive individuals. Death may result from regional or distant metastases, as well as intracranial spread.Citation55,Citation67 Therefore, antiretroviral therapy (ART)-center referral is mandatory in every single OSSN patient with positive serology for a complete systemic examination, counseling, and management. The published literature on OSSN and HIV is summarized in .

Table 1 Review of literature including human immunodeficiency virus affected patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia

Diagnosis

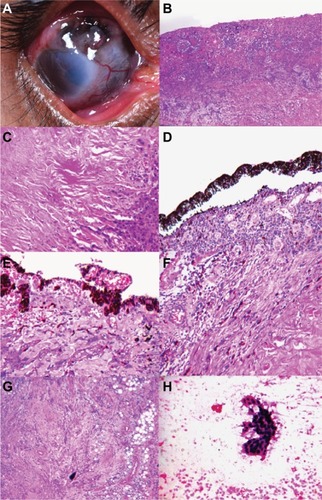

Although OSSN is predominantly a clinical diagnosis, overlap between the clinical features of OSSN and benign lesions sometimes causes difficulty in differentiating between the two.Citation14 Additionally, the occurrence of malignant features on histopathology in pterygia and other benign lesionsCitation68,Citation69 shows that histopathological confirmation is indispensable for a definitive diagnosis of OSSNCitation46 (). Investigative modalities, such as ultrasound biomicroscopy, anterior-segment optical coherence tomography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging, of the orbit are necessary to rule out stromal invasion, corneal/scleral involvement, and intraocular/orbital extension of the tumor.

Figure 2 Clinicopathological correlation of noduloulcerative variant of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients.

Management

Although the management of OSSN in the general population has been well elaborated in numerous studies, current clinical practice in treatment of OSSN in HIV-positive individuals is based on limited medical literature. There is little information about various treatment modalities currently used against this tumor or their outcomes in patients with HIV. The treatment of OSSN in patients with HIV/AIDS depends on the tumor laterality, extent, invasion into adjacent structures, and overall systemic status. The most commonly performed treatment modality for resectable tumors (fewer than two quadrants) with well-defined lesions is surgical management by wide excision. The main objective of surgical excision is complete removal of the tumor to minimize recurrence.Citation70 Wide excision biopsy is executed by a “no-touch” technique with 4 mm tumor-free margins for conjunctival component and alcohol keratoepitheliectomy with 2 mm tumor-free margins for corneal component, followed by adjunct double-freeze–thaw cryotherapy to the surrounding resected conjunctival margins and OS reconstruction by direct closure or amniotic membrane graft, based on the size of the surgical defect.Citation32,Citation70,Citation71

Partial lamellar sclerectomy is needed in cases with clinical evidence of scleral invasion. Adjunctive cryotherapy is applied to the tumor bed after tumor excision in cases with episcleral fixity, scleral invasion on imaging, or adherence of lesion to the base during the surgery.Citation32 Concomitant primary simple limbal epithelial transplantation after wide excisional biopsy for OSSN involving >3 clock hours prevents LSCD in cases requiring extensive corneoscleral limbal dissection ≥6 clock hours during surgery.Citation72

Diffuse tumors (≥three quadrants of the OS) and large annular lesions can be managed by chemoreduction/chemotherapy with topical agents, such as mitomycin-C, cidofovir, and 5-fluorouracil,Citation74–Citation77 or immunoreduction/immunotherapy with topical and perilesional injection IFNα2b.Citation73,Citation77,Citation78 Chemoprevention with topical chemotherapeutic agents or immunoprevention with topical IFNα2b can be considered in patients with microscopic tumor residue.Citation72,Citation74

Extended enucleation with cryotherapy to the resected conjunctival margins is ideal for tumors with intraocular extension or those with entire OS involvement, including fornices. Orbital exenteration is needed for tumors with orbital extension based on computed-tomography scan of the orbit.Citation33,Citation45,Citation72,Citation79 Secondary treatment with plaque radiotherapy is considered in cases with microscopic residual tumors with positive tumor base on histopathology.Citation22,Citation32,Citation40,Citation80,Citation81 External-beam radiotherapy can be used as an alternative for diffuse lesions.Citation1,Citation44,Citation67 Proton-beam therapy is also suggested as a substitute to enucleation for the treatment of OSSN with intraocular invasion.Citation82

Immunotherapy in OSSN and related concerns in HIV patients

IFNα2b is used in medical treatment of OSSN due to its antiviral and oncostatic effects, as well as its property to activate natural killer cells, which further recognize and destroy tumor cells.Citation83 An intact immune system could be an important connection between IFNα2b therapy and tumor resolution. Therefore, topical IFNα2b may not be an ideal choice for patients with underlying immunosuppression, and it is preferred to switch the treatment to a nonimmunomodulating agent, such as 5-fluorouracil or mitomycin C in this patient population.Citation84 Moreover, in patients with HIV, treatment response could be paradoxical, and lesions may increase in size following the use of IFNα2b. Therefore, serology for HIV is recommended in patients with OSSN before commencing treatment with topical IFNα2b.Citation85

Histopathology

Higher-grade malignancy in the form of stromal, corneal, and scleral invasion has been noted in HIV-positive OSSN patients.Citation7,Citation33 Invasive squamous-cell carcinoma has been noted in 55%–80% of patients with OSSN and HIV, and is associated with reduced prognosis.Citation3,Citation11,Citation32 It is noted that OSSN in HIV-positive patients has higher-grade malignancy with increased tumor invasion, irrespective of the size of lesion or age at presentation.Citation7

Recurrence of OSSN in HIV population

Recurrence rates after complete surgical excision of OSSN in the general population vary between 5% and 33% in various studies from Australia, the US, and Canada.Citation36,Citation38,Citation44,Citation45,Citation65,Citation86,Citation87 In a study from the US, a recurrence rate of 28.5% was noted with simple excisional biopsy, which decreased to 7.7% when combined with cryotherapy.Citation87 About 43% of patients experienced recurrence after treatment with topical medications.Citation75,Citation86

Furthermore, HIV-positive OSSN patients have also shown high recurrence after surgical excision.Citation1,Citation6–Citation15,Citation17,Citation19,Citation31,Citation33,Citation42,Citation49,Citation50,Citation55,Citation88 Recurrence rates of 3%–43% were noted postsurgery in several studies from Africa,Citation3,Citation4,Citation7,Citation11,Citation21,Citation39,Citation45,Citation56 frequently occurring during 6 months of follow-up. High recurrence rates in Africa may be due to late presentation, poor surgery with incomplete or simple excision, and unavailability of adjunctive therapies, such as cryotherapy and chemotherapy, and amniotic membranes.Citation45 However, a study from India also documented high recurrence of 30% in HIV-positive patients compared to 20% in HIV-negative patients, despite adjunctive cryotherapy following wide surgical excision of OSSN.Citation33

The standardized surgical procedure for conjunctival tumors described by Shields et al is fundamental in minimizing recurrences, irrespective of HIV status.Citation55,Citation70 Combined treatment with surgical excision and topical IFNα2b might reduce the risk of recurrence or new tumors in eyes with advanced disease.Citation55,Citation89 It is not clear whether these interventions have different efficacy in people with HIV infection. However, postoperative topical 5-FU drops have been shown to reduce the recurrence of OSSN in HIV patients.Citation52,Citation90

Moreover, accurate documentation of histopathology reports, including interpretations about the base and margins of the tumor, is mandatory. Tabin et al validated the importance of excision margins at the time of surgery in predicting recurrence. They observed that recurrence was 33% in completely excised tumors, but 56% in incompletely excised lesions with mild–severe dysplasia in surgical margins.Citation65 They described that in intraepithelial lesions, the most important factor for tumor recurrence was incomplete tumor excision, not histologic depth of the lesion.Citation60 It has been noted that disease prognosis depends on the grades and types of OSSN, with worse prognosis in mucoepidermoid and spindle-cell carcinoma, but recurrence rates have not been compared with them.Citation91

Cases with poor response or tumor recurrence after topical mitomycin C treatment and residual/recurrent tumors after excisional biopsy require appropriate secondary treatment. Protocol for positive margins includes repeated surgical resection or topical IFNα2b (1 million IU/mL).Citation71 Despite aggressive treatment, patients with advanced disease or multiple recurrences are prone to develop intraocular invasion, with subsequent need for enucleation or orbital exenteration.Citation71,Citation92

Posttreatment follow-up

As the majority of tumors recur within 6 months of treatment, frequent follow-up is recommended post-operatively at 1 week, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months, and subsequently at 6-monthly intervals till 2 years after treatment.Citation45 Recurrent lesions have slow growth and malignant potential, and thus lifelong annual follow-up is mandatory for all patients with a history of OSSN.Citation65 Patient counseling is crucial, with an emphasis on regular follow-up and early presentation to an ophthalmologist for any symptoms in the unaffected eye.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy and OSSN

The effect of highly active ART (HAART) on OSSN is controversial.Citation45 According to a study by Guech-Ongey et al, HAART does not reduce the incidence of OSSN.Citation93 However, complete regression of invasive OSSN with HAART alone has been reported in a patient 6 months after initiation of treatment,Citation94 though anecdotal evidence suggests that in patients who develop the malignancy prior to commencing HAART, HAART does not interrupt tumor growth or recurrence.Citation63

With the introduction of HAART, HIV/AIDS has gradually transformed from an acute and fatal disease into a treatable chronic condition with increased survival. This may lead to a possible increase in the disease burden of OSSN, as well as prevalence of bilateral OSSN.Citation63 Strategies for the long-term management of ophthalmic disorders for HAART responders are important. In developed regions, especially the US and Europe, most patients experience a rise in CD4 lymphocytes during the first few months of HAART. This is followed by reduction in opportunistic infections involving the posterior segment, which frequently occur in advanced HIV/AIDS.Citation95,Citation96 On the other hand, the majority of HIV-infected people have no access to HAART in developing countries, and hence develop other HIV-related ocular complications before reaching levels of immunosuppression so as to cause Cytomegalovirus retinitis.Citation37 Therefore, anterior-segment involvement by HIV appears to predominate in the HAART era, and thus attention should be focused on these disorders for early diagnosis and treatment.Citation97

Association with CD4 counts

OSSN can occur at any time in the disease course of HIV/AIDS. It is hypothesized that altered tumor surveillance on the OS in addition to decreased circulating CD4 T cells can aid in the development of conjunctival and corneal lesions. However, no significant trend has been discovered between CD4 count and grade of OSSN.Citation5,Citation7,Citation20 It is speculated that immunosuppression resulting from HIV plays a role in the etiopathogenesis of OSSN. Therefore, CD4 monitoring is recommended in all OSSN patients affected by HIV. A CD4 lymphocyte count <200 cells/mm3 has been noted in 85%–100% patients at the time of OSSN detection.Citation7,Citation11,Citation42 These cell counts indicate that a majority of HIV-positive patients with OSSN are significantly immunosuppressed at presentation. However, a linear relationship between OSSN presentation and CD4 lymphocyte count or initiation of HAART has not been confirmed.Citation5,Citation6 It is suggested that OSSN be considered a criterion to commence AR treatment in HIV-positive patients in African countries with financial and technological restraints when CD4 counts are not accessible.Citation7,Citation29

Serotesting for HIV in OSSN patients

Previously, HIV screening was advised in patients presenting with OSSN at a younger age (<40 years) and with a history of rapid tumor growth (<6 months). The current recommendation is to conduct HIV screening in all cases presenting with OSSN to rule out undiagnosed HIV infection, especially in those <60 years, atypical conjunctival lesions at presentation, large lesions, bilateral or multifocal tumors, and history of aggressive tumor growth.Citation32 In an era of increasing global travel, young patients from countries with high HIV prevalence and high ultraviolet B-radiation exposure should be given a low threshold for serotesting and excision biopsy.Citation66

Comments and recommendations

Africa is the global epicenter of the HIV/AIDS pandemic,Citation98 a region with the highest prevalence of HPV in the world and high solar ultraviolet exposure year-round.Citation99 In the presence of this triad of risk factors, the number of cases of OSSN is expected to stay high. After the introduction of HAART, HIV/AIDS has progressively changed into a nonfatal chronic disease with increased life expectancy. This may lead to a possible increase in the burden of patients living with HIV and OSSN prevalence subsequently in countries with limited resources.Citation5,Citation19,Citation63,Citation100

Large unsightly lesions in the eye expose affected persons to the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV infection, and untreated tumors threaten survival. Without an orbital prosthesis, the cosmetic outcome of advanced disease after orbital exenteration is very poor, which leads to facial disfigurement and limited social interaction subsequently. Orbital prosthesis and facilities for periocular reconstruction are often unavailable in low-income countries.

Treatment of opportunistic tumors in HIV/AIDS is a very important component in HIV care. HIV/AIDS research should focus on treatment of this tumor. Further understanding of the correlation between HIV and OSSN would be of great significance, because of the potential to reduce the spread of HIV with early diagnosis and to reduce morbidity in already immunosuppressed individuals. It is imperative to improve our understanding of this condition so that we can identify and manage it better as it becomes more common.

Effective evidence-based interventions are needed to allow early diagnosis and treatment. Active search for early manifestations of OSSN, early and complete surgical excision, and close follow-up to address current high recurrence rates is recommended. No randomized controlled trials on the effectiveness of interventions against OSSN in HIV-infected individuals were identified in this review. The majority of studies from the developed world have small samples, due to the rarity of the condition. More studies need to be conducted in regions with high disease prevalence so that results can be extrapolated. There is a need to explore the alternative methods like the use of topical antimetabolites alone or in combination with surgery in early OSSN. Efficacy of new techniques used in the developed world, such as amniotic membrane transplant and photodynamic therapy, need to be assessed.

Practical and inexpensive ways of preventing OSSN in the HIV population should be recognized in view of the gradual rise in incidence of the disease. Interventions to reduce the mutagenic effects of solar ultraviolet B radiation, such as protective sunglasses, and the scope for development of HPV vaccination for oncogenic viruses associated with this disease need to be identified.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided by the Operation Eyesight Universal Institute for Eye Cancer (SK) and Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation (SK), Hyderabad, India.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LeeGAHirstLWOcular surface squamous neoplasiaSurv Ophthalmol19953964294507660300

- BastiSMacsaiMSOcular surface squamous neoplasia: a reviewCornea200322768770414508267

- ChisiSKKollmannMKKarimurioJConjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection seen at two hospitals in KenyaEast Afr Med J200683526727016866221

- NkomazanaOTshitswanaDOcular complications of HIV infection in sub-Sahara AfricaCurr HIV/AIDS Rep20085312012518627660

- GichuhiSSagooMSWeissHABurtonMJEpidemiology of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in AfricaTrop Med Int Health201318121424144324237784

- Guech-OngeyMEngelsEGoedertJBiggarRMbulaiteyeSElevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva among adults with AIDS in the United StatesInt J Cancer2008122112590259318224690

- MakupaIISwaiBMakupaWUWhiteVALewallenSClinical factors associated with malignancy and HIV status in patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, TanzaniaBr J Ophthalmol201296448248422075543

- OsahonAIUkponmwanCUUhunmwanghoOMPrevalence of HIV seropositivity among patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctivaAsian Pac J Trop Biomed20111215015323569747

- MahomedAChettyRHuman immunodeficiency virus infection, Bcl-2, p53 protein, and Ki-67 analysis in ocular surface squamous neoplasiaArch Ophthalmol2002120555455812003603

- Ateenyi-AgabaCConjunctival squamous-cell carcinoma associated with HIV infection in Kampala, UgandaLancet199534589516956967885126

- WaddellKMLewallenSLucasSBAtenyi-AgabaCHerringtonCSLiombaGCarcinoma of the conjunctiva and HIV infection in Uganda and MalawiBr J Ophthalmol19968065035088759259

- PorgesYGroismanGMPrevalence of HIV with conjunctival squamous cell neoplasia in an African provincial hospitalCornea20032211412502938

- NewtonRZieglerJAteenyi-AgabaCThe epidemiology of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in UgandaBr J Cancer200287330112177799

- GichuhiSMachariaEKabiruJClinical presentation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in KenyaJAMA Ophthalmol2015133111305131326378395

- SteeleKTSteenhoffAPBissonGPNkomazanaOOcular surface squamous neoplasia among HIV-infected patients in BotswanaS Afr Med J2015105537938326242668

- KarpCLScottIUChangTSPflugfelderSCConjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia: a possible marker for human immunodeficiency virus infection?Arch Ophthalmol199611432572618600883

- KarciogluZAWagonerMDDemographics, etiology, and behavior of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in the 21st centuryOphthalmology2009116112045204619883851

- CarreiraHCoutinhoFCarrilhoCLunetNHIV and HPV infections and ocular surface squamous neoplasia: systematic review and meta-analysisBr J Cancer201310971981198824030075

- KheirWJTetzlaffMTPfeifferMLEpithelial, non-melanocytic and melanocytic proliferations of the ocular surfaceSemin Diagn Pathol201633312213227021909

- World Health OrganizationHIV/AIDS2017 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/enAccessed October 12, 2017

- MasanganiseRRusakanikoSMakunikeRA historical perspective of registered cases of malignant ocular tumors in Zimbabwe (1990 to 1999): is HIV infection a factor?Cent Afr J Med2008545–8283221650077

- BelfortRJrThe ophthalmologist and the global impact of the AIDS epidemic: LV Edward Jackson Memorial LectureAm J Ophthalmol200012911810653405

- WabingaHRParkinDMWabwire-MangenFNamboozeSTrends in cancer incidence in Kyadondo County, Uganda, 1960–1997Br J Cancer20008291585159210789729

- ParkinDMWabingaHNamboozeSWabwire-MangenFAIDS-related cancers in Africa: maturation of the epidemic in UgandaAIDS199913182563257010630526

- OremJOtienoMWRemickSCAIDS-associated cancer in developing nationsCurr Opin Oncol200416546847615314517

- ChokunongaELevyLMBassettMTAIDS and cancer in Africa: the evolving epidemic in ZimbabweAIDS199913182583258810630528

- NewtonRA review of the aetiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctivaBr J Cancer19967410151115138932327

- TorneselloMLDuraturoMLWaddellKMEvaluating the role of human papillomaviruses in conjunctival neoplasiaBr J Cancer200694344644916404433

- ChinogureiTSMasanganiseRRusakanikoSSibandaEOcular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) and human immunodeficiency virus at Sekuru Kaguvi Eye Unit in Zimbabwe: the role of operational research studies in a resource poor environment?Cent Afr J Med2006525–6565818254456

- KestelynPHStevensAMNdayambajeAHanssensMvan de PerrePHHIV and conjunctival malignanciesLancet199033687065152

- SpitzerMSBatumbaNHChiramboTOcular surface squamous neoplasia as the first apparent manifestation of HIV infection in MalawiClin Exp Ophthalmol200836542242518939345

- KalikiSKamalSFatimaSOcular surface squamous neoplasia as the initial presenting sign of human immunodeficiency virus infection in 60 Asian Indian patientsInt Ophthalmol Epub2016118

- KamalSKalikiSMishraDKBatraJNaikMNOcular surface squamous neoplasia in 200 patients: a case-control study of immunosuppression resulting from human immunodeficiency virus versus immunocompetencyOphthalmology201512281688169426050538

- FrischMBiggarRJGoedertJJHuman papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndromeJ Natl Cancer Inst200092181500151010995805

- GoedertJCotéTConjunctival malignant disease with AIDS in USALancet19953468969257258

- LeeGAHirstLWRetrospective study of ocular surface squamous neoplasiaAust N Z J Ophthalmol19972532692769395829

- PooleTRConjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in TanzaniaBr J Ophthalmol199983217717910396194

- McKelviePADaniellMMcNabALoughnanMSantamariaJDSquamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: a series of 26 casesBr J Ophthalmol200286216817311815342

- KaimboDWParys-van GinderdeurenRMissottenLConjunctival squamous cell carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia in AIDS patients in Congo KinshasaBull Soc Belge Ophtalmol19982681351419810095

- TimmAStropahlGSchittkowskiMSinzidiCKayembeDGuthoffRAssociation of malignant tumors of the conjunctiva and HIV infection in Kinshasa (DR Congo): first resultsOphthalmologe20041011010111016 German15185119

- PolaECMasanganiseRRusakanikoSThe trend of ocular surface squamous neoplasia among ocular surface tumour biopsies submitted for histology from Sekuru Kaguvi Eye Unit, Harare between 1996 and 2000Cent Afr J Med2003491–21414562592

- PradeepTGGangasagaraSBSubbaramaiahGBSureshMBGangashettappaNDurgappaRPrevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection in patients with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in a tertiary center in Karnataka, south IndiaCornea201231111282128422673850

- SunECFearsTRGoedertJJEpidemiology of squamous cell conjunctival cancerCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev19976273779037556

- CervantesGRodríguezAALealAGSquamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: clinicopathological features in 287 casesCan J Ophthalmol2002371142011865953

- GichuhiSIrlamJJInterventions for squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva in HIV-infected individualsCochrane Database Syst Rev20072CD00564317443606

- TuncMCharDHCrawfordBMillerTIntraepithelial and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: analysis of 60 casesBr J Ophthalmol19998319810310209445

- NakamuraYMashimaYKameyamaKMukaiMOguchiYDetection of human papillomavirus infection in squamous tumours of the conjunctiva and lacrimal sac by immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridisation, and polymerase chain reactionBr J Ophthalmol19978143083139215061

- Ateenyi-AgabaCDaiMle CalvezFTP53 mutations in squamous-cell carcinomas of the conjunctiva: evidence for UV-induced mutagenesisMutagenesis200419539940115388813

- GichuhiSMachariaEKabiruJRisk factors for ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya: a case-control studyTrop Med Int Health201621121522153027714903

- KiireCADhillonBThe aetiology and associations of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasiaBr J Ophthalmol200690110911316361679

- WinwardKECurtinVTConjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infectionAm J Ophthalmol198910755545552712140

- GichuhiSEpidemiology and Management of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia in Kenya [doctoral thesis]LondonLondon School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine2016

- Ateenyi-AgabaCFranceschiSWabwire-MangenFHuman papillomavirus infection and squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctivaBr J Cancer2010102226226719997105

- de KoningMNWaddellKMagyeziJGenital and cutaneous human papillomavirus (HPV) types in relation to conjunctival squamous cell neoplasia: a case-control study in UgandaInfect Agent Cancer200831218783604

- ShieldsCLRamasubramanianAMellenPLShieldsJAConjunctival squamous cell carcinoma arising in immunosuppressed patients (organ transplant, human immunodeficiency virus infection)Ophthalmology2011118112133213721762990

- LewallenSShroyerKRKeyserRBLiombaGAggressive conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in three young AfricansArch Ophthalmol199611422152188573029

- MacleanHDhillonBIronsideJSquamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid and the acquired immunodeficiency syndromeAm J Ophthalmol199612122192218623898

- SafaiBLynfieldRLowenthalDAKozinerBCancers-associated with HIV infectionAnticancer Res198775B105510673324937

- LeeGAHirstLWIncidence of ocular surface epithelial dysplasia in metropolitan Brisbane: a 10-year surveyArch Ophthalmol199211045255271562262

- CackettPGilliesMLeenCDhillonBConjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia in association with HIV infectionAIDS200519335135215718850

- KalikiSFreitagSKChodoshJNodulo-ulcerative ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 6 patients: a rare presentationCornea201736332232627749454

- KabraRCKhaitanIAComparative analysis of clinical factors associated with ocular surface squamous neoplasia in HIV infected and non HIV patientsJ Clin Diagn Res201595NC01NC03

- MasanganiseRMukomeADariJMakunike-MutasaRBilateral HIV related ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a paradigm shiftCent Afr J Med2010565–8232623457846

- KimRYSeiffSRHowesELO’DonnellJJNecrotizing scleritis secondary to conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in acquired immunodeficiency syndromeAm J Ophthalmol199010922312332301539

- TabinGLevinSSnibsonGLoughnanMTaylorHLate recurrences and the necessity for long-term follow-up in corneal and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasiaOphthalmology199710434854929082277

- De SilvaDJTumuluriKJoshiNConjunctival squamous cell carcinoma: atypical presentation of HIVClin Exp Ophthalmol200533441942016033363

- TabbaraKFKerstenRDaoukNBlodiFCMetastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctivaOphthalmology19889533183213173999

- OellersPKarpCLShethAPrevalence, treatment, and outcomes of coexistent ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygiumOphthalmology2013120344545023107578

- HirstLWAxelsenRASchwabIPterygium and associated ocular surface squamous neoplasiaArch Ophthalmol20091271313219139334

- ShieldsJAShieldsCLde PotterPSurgical management of conjunctival tumors: the 1994 Lynn B McMahan LectureArch Ophthalmol199711568088159194740

- TsatsosMKarpCLModern management of ocular surface squamous neoplasiaExpert Rev Ophthalmol201383287295

- KalikiSMohammadFATahilianiPSangwanVSConcomitant simple limbal epithelial transplantation after surgical excision of ocular surface squamous neoplasiaAm J Ophthalmol2017174Suppl C687527832940

- ShieldsCLKalikiSKimHJInterferon for ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 81 cases: outcomes based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer classificationCornea201332324825622580436

- ShieldsCLNaseripourMShieldsJATopical mitomycin C for extensive, recurrent conjunctival-corneal squamous cell carcinomaAm J Ophthalmol2002133560160611992855

- MidenaEAngeliCDValentiMde BelvisVBoccatoPTreatment of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma with topical 5-fluorouracilBr J Ophthalmol200084326827210684836

- ShermanMDFeldmanKAFarahmandSMMargolisTPTreatment of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma with topical cidofovirAm J Ophthalmol2002134343243312208255

- BesleyJPappalardoJLeeGAHirstLWVincentSJRisk factors for ocular surface squamous neoplasia recurrence after treatment with topical mitomycin C and interferon α2BAm J Ophthalmol2014157228729324184223

- KarpCLGalorAChhabraSBarnesSDAlfonsoECSubconjunctival/perilesional recombinant interferon α2B for ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a 10-year reviewOphthalmology2010117122241224620619462

- ShieldsJAShieldsCLSuvarnamaniCTantisiraMShahPOrbital exenteration with eyelid sparing: indications, technique, and resultsOphthalmic Surg19912252922971852385

- Walsh-ConwayNConwayRMPlaque brachytherapy for the management of ocular surface malignancies with corneoscleral invasionClin Exp Ophthalmol20093765778319702707

- ArepalliSKalikiSShieldsCLEmrichJKomarnickyLShieldsJAPlaque radiotherapy in the management of scleral-invasive conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma: an analysis of 15 eyesJAMA Ophthalmol2014132669169624557333

- RamonasKMConwayRMDaftariIKCrawfordJBO’BrienJMSuccessful treatment of intraocularly invasive conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma with proton beam therapyArch Ophthalmol2006124112612816401797

- LakeDFBriggsADAkporiayeETImmunopharmacologyKatzungBGBasic and Clinical Pharmacology9th edBostonMcGraw-Hill2004931957

- AshkenazyNKarpCLWangGAcostaCMGalorAImmunosuppression as a possible risk factor for interferon nonresponse in ocular surface squamous neoplasiaCornea201736450651028129301

- MataEConesaECastroMMartínezLde PabloCGonzálezMLConjunctival squamous cell carcinoma: paradoxical response to interferon eyedropsArch Soc Esp Oftalmol2014897293296 Spanish24269461

- Frucht-PeryJSugarJBaumJMitomycin C treatment for conjunctival-corneal intraepithelial neoplasia: a multicenter experienceOphthalmology199710412208520939400769

- SudeshSRapuanoCJCohenEJEagleRCJrLaibsonPRSurgical management of ocular surface squamous neoplasms: the experience from a cornea centerCornea200019327828310832683

- FoglaRBiswasJKumarSKKumarasamyNMadhavanHNSolomonSSquamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva as initial presenting sign in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) due to human immunodeficiency virus type-2Eye (Lond)200014224624710845028

- SiedleckiANTappSTostesonANSurgery versus interferon α2B treatment strategies for ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a literature-based decision analysisCornea201635561361826890663

- GichuhiSMachariaEKabiruJTopical fluorouracil after surgery for ocular surface squamous neoplasia in Kenya: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet Glob Health201646e378e38527198842

- MittalRRathSVemugantiGKOcular surface squamous neoplasia: review of etio-pathogenesis and an update on clinico-pathological diagnosisSaudi J Ophthalmol201327317718624227983

- ShieldsJAShieldsCLGunduzKEagleRCThe 1998 Pan American Lecture: Intraocular invasion of conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma in five patientsOphthal Plast Reconstr Surg1999153153160

- Guech-OngeyMEngelsEAGoedertJJBiggarRJMbulaiteyeSMElevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva among adults with AIDS in the United StatesInt J Cancer2008122112590259318224690

- HolkarSMudharHSJainARegression of invasive conjunctival squamous carcinoma in an HIV-positive patient on antiretroviral therapyInt J STD AIDS2005161278278316336757

- ForrestDMSeminariEHoggRSThe incidence and spectrum of AIDS-defining illnesses in persons treated with antiretroviral drugsClin Infect Dis1998276137913859868646

- PalellaFJDelaneyKMMoormanACDeclining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infectionN Engl J Med1998338138538609516219

- JengBHHollandGNLowderCYDeeganWFRaizmanMBMeislerDMAnterior segment and external ocular disorders associated with human immunodeficiency virus diseaseSurv Ophthalmol200752432936817574062

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDSGlobal report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic — 2010 Available from: http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/globalreport.htm2010Accessed October 12, 2017

- CliffordGMGallusSHerreroRWorldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: a pooled analysisLancet2005366949099199816168781

- ReynoldsJWPfeifferMLOzgurOEsmaeliBPrevalence and severity of ocular surface neoplasia in African nations and need for early interventionsJ Ophthalmic Vis Res201611441542127994810