Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to assess fertility intentions (planning to have more children in the future) and associated factors among pregnant and postpartum HIV positive women in rural South Africa.

Methods

In a longitudinal study, as part of a prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) intervention trial, 699 HIV positive prenatal women, were systematically recruited and followed up at 6 months and 12 months postpartum (retention rate = 59.5%).

Results

At baseline, 32.9% of the women indicated fertility intentions and at 12 months postnatal, 120 (28.0%) reported fertility intentions. In longitudinal analyses, which included time-invariant baseline characteristics predicting fertility intention over time, not having children, having a partner with unknown/HIV-negative status, and having disclosed their HIV status to their partner, were associated with fertility intentions. In a model with time-varying covariates, decreased family planning knowledge, talking to a provider about a future pregnancy, and increased male involvement were associated with fertility intentions.

Conclusion

Results support ongoing perinatal family planning and PMTCT education.

Introduction

South Africa had an estimated 6,300,000 people living with HIV (PLHIV) in 2013Citation1 and HIV prevalence among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics was 29.7%.Citation1 Antiretroviral therapy (ART)Citation2 and interventions to prevent mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIVCitation3 have greatly reduced the impact of HIV on health and life expectancy for mothers, children, and sexual partners.Citation4 With the appropriate resources and support, having a healthy pregnancy and HIV-negative child are now attainable goals, and understanding and supporting the fertility intentions, that is, desire to have children, of PLHIV can improve linkages to and effectiveness of these services.

Understanding factors related to motivation for childbearing may guide health care providers as they initiate discussions regarding childbearing intentions and may help them to address topics such as safer conception and pregnancy planning. Discussing reproductive desires with a health care provider is an element of the PMTCT guidelines and has been associated with increased fertility intentions,Citation5,Citation6 though PLHIV have reported that reproductive discussions with their health care providers are infrequent.Citation7–Citation9 Many PLHIV also report a lack of trust that their health care providers will provide unbiased information and support.Citation10–Citation12

Conflicting evidence exists regarding the influence of HIV-specific factors on fertility intentions among PLHIV, that is, the length of time since HIV diagnosis,Citation13–Citation16 time since ART initiation,Citation7,Citation14,Citation17 disclosure of HIV serostatus to partners,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 the HIV serostatus of partners,Citation7,Citation18,Citation20,Citation21 level of education,Citation15,Citation22,Citation23 income,Citation24–Citation26 and PMTCT knowledge.Citation11,Citation19,Citation27,Citation28 Similarly, concerns regarding welfare of the family, including potential HIV transmission to infantsCitation21,Citation29,Citation30 or partners,Citation10,Citation21,Citation31 monetary concerns,Citation29,Citation32,Citation33 and fears regarding maternal mortalityCitation10,Citation31,Citation33–Citation35 have been reported as considerations among PLHIV with regard to future pregnancies. Cultural factors, spousal, familial, and societal support, social expectations and attitudes, including stigma, also impact fertility intentions.Citation30 However, these issues underscore the importance of the relationship between fertility intentions and the level of importance the individuals place on these factors.

Relationship factors, such as intimate partner violence (IPV) and male involvement during pregnancy planning and perinatal care, play a potential role in fertility intentions due to their impact on relationship quality. Depression, which has been associated with IPV,Citation36 may also impact fertility intentions, which require future-oriented thinking.Citation37 In addition, HIV and family planning knowledge may influence fertility intentions as concerns with regard to the risk of HIV transmission during pregnancy have been reported.Citation21,Citation29 Factors related to prior pregnancies, including unplanned pregnancy and HIV diagnosis during pregnancy, appear likely to also influence attitudes and plans with regard to future pregnancy.

Despite the volume of research on fertility intentions among PLHIV, studies have neglected the potential changes that occur in intentions following delivery. Rather, the few longitudinal studies of intentions among PLHIV have focused on comparisons between HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women, for example,Citation38 or the relative influence of ART. This study seeks to address this gap in research by exploring factors associated with existing or changing fertility intentions during the antenatal and/or postnatal period, addressing understudied factors associated with relationships, health, and knowledge. Care during the perinatal period provides a window of opportunity for linkage to and uptake of HIV treatment services,Citation39 and information, therefore, regarding intentions assessed throughout the perinatal period may be especially important.

Patients and methods

Study design

This study is drawn from an ongoing longitudinal clinic-randomized PMTCT-controlled trial with 2 assessments prenatally (8–24 and 32 weeks pregnant) and 2 assessments during the postnatal period (6 and 12 months). The trial is aimed at increasing PMTCT uptake, family planning, and male partner participation in the antenatal and postnatal process in 12 randomly selected community health centers in Gert Sibande and Nkangala districts in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Further details about the study design, staff training, subject recruitment, and procedures have been previously reported.Citation40

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Research Ethics Committee (REC), protocol approval number REC4/21/08/13, and the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB ID: 20130238) (CR00006122). Study approval was also obtained from the Department of Health and Welfare, Mpumalanga Provincial Government, South Africa. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sample and procedure

Eligible women were HIV-seropositive pregnant women with partners, between 8 and 24 weeks pregnant, the typical time of entry into antenatal care, and aged ≥18 years. Candidates agreeing to participate were enrolled following provision of written informed consent. There were no exclusions based on literacy as all assessments were administered using an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) system.

After enrollment, all women completed study measures in their preferred language (English, isiZulu, or seSotho) using ACASI to enhance disclosure, accommodate all levels of literacy, and reduce interviewer bias. To familiarize participants with the computer system, assessors completed the demographic component of the questionnaire with participants prior to completion of all other assessments. In addition, an on-site assessor was available to assist where necessary and answer any questions.

Measures

Fertility intentions were assessed with the question, “Are you planning to have more children in the future?” (response option, yes, no). Sociodemographic factors assessed included age, education, income, partner status, and number of children. Reproductive issues assessed included planning of the current pregnancy, talking to a health care provider about future pregnancy, and an 8-item measure of family planning knowledge.Citation40 Family planning knowledge items assessed perception of risk of transmission to the partner during pregnancy as well as knowledge of the fertility cycle and ideal time to conceive, with heterogeneous response options. Knowledge of safer conception practices was also assessed.Citation41 HIV-specific issues assessed included date of HIV diagnosis, a 12-item measure on HIV knowledge (Cronbach’s α=0.69, 0.64, 0.52, and 0.65 at the 2 prenatal and postnatal assessment points, respectively) using an adaptation of the AIDS-Related Knowledge Test to South African context; items reflect information about HIV transmission, reinfection with resistant virus, and condom use knowledge.Citation42 Partner-specific issues assessed included disclosure of HIV status to partner, HIV status of partner, consistency of condom use, and an 11-item male involvement indexCitation40 (Cronbach’s α=0.83, 0.82, 0.84, and 0.82 at the 2 prenatal and postnatal assessment points, respectively). IPV was assessed using an adaptation of the Conflict Tactics Scale 18,Citation43 which included a 9-item partner psychological victimization subscale (Cronbach’s α=0.76, 0.66, 0.83, and 0.83 at the 2 prenatal and postnatal assessment points, respectively), and a 9-item partner physical violence subscale (Cronbach’s α=0.92, 0.89, 0.94, and 0.94 at the 4 assessment points). Emotional status was assessed at baseline with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale 10 (EPDS-10).Citation44 The EPDS-10 is a 10-item instrument asking participants to rate how often they have experienced different symptoms associated with depression in the past 7 days. Scores range from 0 through 30; the validated cut-off score for South African populations is 12.Citation45 Cronbach’s α for the EPDS-10 scale ranged from 0.66 to 0.70 at the different assessment points in this study sample.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics (such as means, SDs, frequencies, and percentages), Student’s t-tests or its non-parametric alternative (Mann–Whitney Z-test), as well as chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. The dependent variable consisted of women living with HIV and whether they had a desire to have more children at baseline, 32 weeks assessment, and 6 and 12 months assessments.

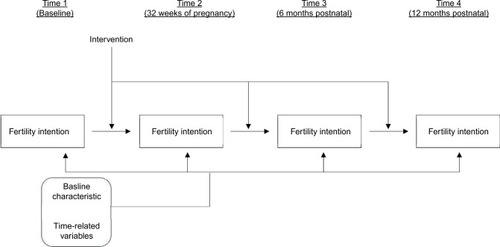

To investigate patterns the participants’ binary responses (yes/no) for fertility intention between 2 adjacent time points (time and time +1), we used the autoregressive model (also known as “Markov chain model”),Citation46 which tested how fertility intention at one time point predicted fertility intention at the next time point. Then, using multigroup test approach, we investigated the effects of intervention on response changes in fertility intention. The hypothesized autoregressive model for fertility intention continuity is presented in . According to this approach, the same autoregressive model was estimated using 2 groups (standard of care vs. enhanced intervention) simultaneously. Multigroup analysis is useful to test for differences (Δ) using the “parameter invariance” method.Citation47 Given the categorical (binary) outcomes, logistic regression coefficients were estimated with odds-ratios (ORs, as effect sizes of logistic coefficients).Citation48 To estimate unique autoregressive associations of fertility intention, the current model used several time-invariant (baseline demographic variables) and varying covariates as control variables. In addition, to account for lack of independence between observations within multiple sites, we used a sandwich estimator to adjust for underestimated standard errors and bias in chi-square computation.Citation49 Missing data were handled using multiple imputationCitation50 after comparing it with inverse-probability treatment weighting, specifying 10 imputed datasets. All data analyses were conducted using Mplus (version 7.4).Citation51

Results

Sample characteristics at baseline

In all, 699 women living with HIV were enrolled during pregnancy (8–24 weeks) and completed assessments at baseline; 61.7% of the sample completed assessments at 32 weeks pregnant; 50.6% postnatal at 6 months; and 59.5% at 12 months. At baseline, 224 women (32.9%) indicated that they were “planning to have more children in the future” (fertility intentions).

Attrition analyses indicated that women with more education, those who already had children, and those who had an HIV-infected infant (OR=0.64, p<0.10) were less likely to drop out of the study over time, and these variables were accounted for in all subsequent analyses. Other demographic and psychosocial variables, such as age, income, HIV-infected partner, disclosure of HIV status to partner, depression, and relationship status were not found to predict missing data over time.

describes baseline characteristics, overall and by fertility intention. Women were, on average, aged 28.4 years, the majority (71.1%) had grade 10–11 education, 51.1% had a household income of ≥600 Rand a month, 20.2% had no children, and 53.0% reported that the current pregnancy had been unplanned. Almost half (47.1%) had talked to their health care provider about trying to get pregnant in the future. Slightly more than half (54.1%) of women had been diagnosed with HIV during this pregnancy. As a requirement of eligibility, all women had a partner; 41.1% were married or cohabiting, 59.0% had disclosed their HIV status to their partners, and 25.1% of their partners were known to be infected with HIV. Fertility intentions were more likely to be reported by younger women, those with more education, those having lower income, those with no children or only one child, those having been diagnosed with HIV during this pregnancy, those having a partner and family with high-fertility desires, and those having less HIV and family planning knowledge ().

Table 1 Fertility intention by socioeconomic, reproductive, HIV, partner and mental health characteristics prenatal at baseline

Transition patterns of fertility intention and moderating effects of intervention across 4 time points

Transition patterns showed that overall; women who reported planning to have children at Time 1 were more likely to report planning to have children in all future time points (see ORs in ). Similar response patterns were detected even after adjusting the effects of all time-invarying (baseline characteristics) and varying covariates (see AORs in ). Next, to examine the intervention effects on the transition frequencies for fertility intention, these ORs were compared by condition. After adjusting for time-varying covariates, participants in the experimental group were less likely to plan to have children in the future from time points 1–2 (AORs=13.17 (standard of care) vs 10.26 (enhanced intervention); Wald-test=6.42, p<0.05) and from time points 3–4 (AORs=4.74 [standard of care] vs 3.99 [enhanced intervention]; Wald-test=4.88, p<0.05) compared with those in control group.

Table 2 Transition frequencies (probabilities) of fertility intention and moderating effects of intervention across four timepoints

Effects of baseline characteristics and time-varying covariates on fertility intention across time

In longitudinal analyses, in Model 1, which included time-invariant predictors (at baseline) of fertility intention assessed over 4 time periods, not having children (AOR=0.61, p<0.001), having a partner with unknown/HIV-negative status (AOR=0.76, p<0.01), and having disclosed their HIV status to their partner (AOR=1.25, p<0.05) were associated with fertility intentions. In Model 2, which included time-varying covariates, decreased family planning knowledge (AOR=0.84, p<0.001), talking to a provider about a future pregnancy (AOR=1.34, p<0.01), and increased male involvement (AOR=1.01, p<0.01) were associated with fertility intentions ().

Table 3 Effects of baseline characteristics and time varying covariates on fertility intention across time (n=699)

Discussion

The study examined fertility intentions among women living with HIV during the pre- and postnatal periods, and found less than one-third of women intended to have more children, as previously found.Citation30 As in earlier studies,Citation14,Citation19,Citation23,Citation30,Citation52 younger age and having fewer or no children were associated with intentions to conceive again in the future.

In contrast with previous research, neither educational levelCitation15,Citation22,Citation53 nor incomeCitation24,Citation26 was associated with reproductive desires. This may have been due to a lack of educational and socioeconomic variability in this rural sample, with a largely low-income sample with the majority having attained 10 or 11 years of education. As found in previous studies,Citation20,Citation21,Citation54,Citation55 partner’s HIV-positive status was negatively associated with fertility intentions. Disclosure of HIV serostatus to partners at the baseline assessment, as found previously,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 was positively associated with fertility intentions. Male involvement was associated with fertility intentions, showing the important role of male partners in fertility desires and the promotion of male involvement in the mother and child care continuum.Citation56 Inconsistent condom use was not associated with fertility intentions in this study, as seen in previous studies.Citation21,Citation57–Citation59 This finding may have been associated with local beliefs that women are less likely to conceive following childbirth or due to concerns about insisting on condom use being associated with HIV, as noted previously.

Furthermore, the study found an association between discussing family planning with a health care provider and fertility intentions, as in previous research.Citation60 These findings have been confirmed in several other studies,Citation5,Citation6 and show the importance of the South African Department of Health guidelines in helping facilitate the initiation of discussions about fertility intentions by health care providers with PLHIV. In contrast, family planning knowledge and participation in an enhanced PMTCT intervention, which included information on family planning, were associated with decreased fertility intention. It is possible that better family planning knowledge and having received information on family planning from interventionists may have heightened awareness of risks of HIV transmission during pregnancy or consideration of other issues associated with pregnancy, such that knowledge may be necessary but not sufficient to arrive at fertility intentions. Surprisingly, IPV during the perinatal period, unplanned pregnancy, time since HIV diagnosis, and depression (analysis not shown) were not associated with fertility intentions, contrary to previous research.Citation60 Future research should examine the relative trade-offs in reproductive decision making among this vulnerable population.

Study limitations

Study follow-up rates were lower than the original target and those previously achieved in our pilot studies, and results may have been influenced by self-selection among women who were followed to 12 months postpartum. The high level of attrition and low clinic attendance may have been related to the need for many women to travel long distances to reach the health facility, migration arising from economic necessity, and culturally condoned migration of women during the perinatal period to their mothers’ homes.Citation61 The inclusion criteria for the study participants were limited to women who had a partner, preventing generalization to women without partners. The content of discussions about fertility and pregnancy between couples and with health care providers was not assessed, and should be considered in future studies to gain more insight in fertility and reproductive intentions and their influence by providers.

Conclusion

This study of pregnant women living with HIV demonstrated declining fertility intentions from the prenatal to postnatal period. PMTCT and family planning knowledge, along with sociodemographic factors, were associated with fertility intentions, and individual discussions between patients, providers, and interventionists were associated with diminished desire for more children. Factors identified related to motivation for childbearing may be useful in helping health care providers to initiate and explore fertility-related discussions, and in developing and providing effective and suitable strategies for contraception, safer conception, and pregnancy planning. Future studies should explore the role of culture in fertility intentions, and potential moderation of its influence in the uptake of clinical guidance by providers.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a collaborative NIH/PEPFAR Grant, R01HD078187-S. Activities were conducted with the support of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Center for AIDS Research, funded by NIH grants, P30AI073961 and K23HD074489.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- National Department of HealthThe 2013 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV Prevalence Survey, South AfricaPretoriaNational Department of Health2015

- MahyMStoverJStaneckiKStoneburnerRTassieJMEstimating the impact of antiretroviral therapy: regional and global estimates of life-years gained among adultsSex Transm Infect201086Suppl 2ii67ii7121106518

- SturtASDokuboEKSintTTAntiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating HIV infection in ART-eligible pregnant womenCochrane Database Syst Rev20103CD008440

- CohenMSChenYQMcCauleyMPrevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapyN Engl J Med2011365649350521767103

- AbbawaFAwokeWAlemuYFertility desire and associated factors among clients on highly active antiretroviral treatment at finoteselam hospital Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional studyReprod Health2015126926260021

- SteinerRJBlackVReesHSchwartzSRLow receipt and uptake of safer conception messages in routine HIV Care: findings from a prospective cohort of women living with HIV in South AfricaJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201672110511326855247

- MyerLMorroniCRebeKPrevalence and determinants of fertility intentions of HIV-infected women and men receiving antiretrovi-ral therapy in South AfricaAIDS Patient Care STDS200721427828517461723

- SherrLBarryNFatherhood and HIV-positive heterosexual menHIV Med20045425826315236614

- WestNSchwartzSPhofaR“I don’t know if this is righ …but this is what I’m offering”: healthcare provider knowledge, practice, and attitudes towards safer conception for HIV-affected couples in the context of Southern African guidelinesAIDS Care201628339039626445035

- CooperDHarriesJMyerLOrnerPBrackenH“Life is still going on”: reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South AfricaSoc Sci Med200765227428317451852

- NobregaAAOliveiraFAGalvaoMTDesire for a child among women living with HIV/AIDS in northeast BrazilAIDS Patient Care STDS200721426126717461721

- SowellRLMisenerTRDecisions to have a baby by HIV-infected womenWest J Nurs Res199719156709030038

- GosselinJTSauerMVLife after HIV: examination of HIV serodiscordant couples’ desire to conceive through assisted reproductionAIDS Behav201115246947820960049

- KaidaALaherFStrathdeeSAChildbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyperendemic settingAm J Public Health2011101235035820403884

- KawalePMindryDStramotasSFactors associated with desire for children among HIV-infected women and men: a quantitative and qualitative analysis from Malawi and implications for the delivery of safer conception counselingAIDS Care201426676977624191735

- OladapoOTDanielOJOdusogaOLAyoola-SotuboOFertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive patients at a suburban specialist centerJ Natl Med Assoc200597121672168116396059

- CooperDMoodleyJZweigenthalVBekkerLGShahIMyerLFertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care servicesAIDS Behav200913Suppl 1384619343492

- MelakuYAZelekeEGKinsmanJAbrahaAKFertility desire among HIV-positive women in Tigray region, Ethiopia: implications for the provision of reproductive health and prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission servicesBMC Womens Health20141413725407330

- PeltzerKChaoLWDanaPFamily planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South AfricaAIDS Behav200913597397918286365

- DemissieDBTebejeBTesfayeTFertility desire and associated factors among people living with HIV attending antiretroviral therapy clinic in EthiopiaBMC Pregnancy Childbirth20141438225410125

- HaddadLBMachenLKCordesSFuture desire for children among women living with HIV in Atlanta, GeorgiaAIDS Care201628445545926702869

- AsfawHMGasheFEFertility intentions among HIV positive women aged 18–49 years in Addis Ababa Ethiopia: a cross sectional studyReprod Health2014113624885318

- BerhanYBerhanAMeta-analyses of fertility desires of people living with HIVBMC Public Health20131340923627965

- KimaniJWarrenCAbuyaTFamily planning use and fertility desires among women living with HIV in KenyaBMC Public Health20151590926381120

- SantosNVentura-FilipeEPaivaVHIV positive women, reproduction and sexuality in São Paulo, BrazilReprod Health Matters19986123140

- WekesaECoastEFertility desires among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Nairobi slums: a mixed methods studyPLoS One201498e10629225171593

- Finocchario-KesslerSSweatMDDariotisJKUnderstanding high fertility desires and intentions among a sample of urban women living with HIV in the United StatesAIDS Behav20101451106111419908135

- NakayiwaSAbangBPackelLDesire for children and pregnancy risk behavior among HIV-infected men and women in UgandaAIDS Behav2006104 SupplS95S10416715343

- AskaMLChompikulJKeiwkarnkaBDeterminants of fertility desires among HIV positive women living in the Western Highlands Province of Papua New GuineaWorld J AIDS20110104198207

- NattabiBLiJThompsonSCOrachCGEarnestJA systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for policy and service deliveryAIDS Behav200913594996819330443

- RichterDLSowellRLPlutoDMFactors affecting reproductive decisions of African American women living with HIVWomen Health2002361819612215005

- AkeloVMcLellan-LemalEToledoLDeterminants and experiences of repeat pregnancy among HIV-positive kenyan women–a mixed-methods analysisPLoS One2015106e013116326120846

- FeldmanRMaposhereCSafer sex and reproductive choice: findings from “Positive Women: Voices and Choices” in ZimbabweReprod Health Matters2003112216217314708407

- KanniappanSJeyapaulMJKalyanwalaSDesire for motherhood: exploring HIV-positive women’s desires, intentions and decision-making in attaining motherhoodAIDS Care200820662563018576164

- SowellRLPhillipsKDMisenerTRHIV-infected women and motivation to add children to their familiesJ Fam Nurs199953316331

- PeltzerKRodriguezVJJonesDPrevalence of prenatal depression and associated factors among HIV-positive women in primary care in Mpumalanga province, South AfricaSAHARA J2016131606727250738

- BjärehedJSarkohiAAnderssonGLess Positive or more negative? Future-directed thinking in mild to moderate depressionCogn Behav Ther2010391374519714541

- TauloFBerryMTsuiAFertility intentions of HIV-1 infected and uninfected women in Malawi: a longitudinal studyAIDS Behav200913Suppl 1202719308718

- Watson-JonesDBaliraRRossDAWeissHAMabeyDMissed opportunities: poor linkage into ongoing care for HIV-positive pregnant women in Mwanza, TanzaniaPLoS One201277e4009122808096

- JonesDLPeltzerKVillar-LoubetOReducing the risk of HIV infection during pregnancy among South African women: a randomized controlled trialAIDS Care201325670270923438041

- KayeKSuellentropKSloupCThe Fog Zone: How Misperceptions, Magical Thinking, and Ambivalence Put Young Adults at Risk for Unplanned PregnancyWashington, DCThe National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy2009

- CareyMPSchroderKEDevelopment and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge QuestionnaireAIDS Educ Prev200214217218212000234

- StrausMAMeasuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scalesJ Marriage Fam1979417588

- CoxJLHoldenJMSagovskyRDetection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression ScaleBr J Psychiatry19871507827863651732

- LawrieTAHofmeyrGJde JagerMBerkMValidation of the Edin-burgh Postnatal Depression Scale on a cohort of South African womenS Afr Med J19988810134013449807193

- KaplanDAn overview of Markov chain methods for the study of stage-sequential developmental processesDev Psychol200844245746718331136

- LubkeGHMuthenBOApplying multigroup confirmatory factor models for continuous outcomes to Likert scale data complicates meaningful group comparisonsStruct Equ Modeling2004114514534

- AllenJLeHAn additional measure of overall effect size for logistic regression modelsJ Educ Behav Stat2008334416441

- LiangKYZegerSLLongitudinal data-analysis using generalized linear-modelsBiometrika19867311322

- AsparouhovTMuthénBMultiple Imputation with MplusMPlus Web Notes2010

- Mplus [computer program]. Version 7.4Los Angeles, CA2014

- AntelmanGMedleyAMbatiaRPregnancy desire and dual method contraceptive use among people living with HIV attending clinical care in Kenya, Namibia and TanzaniaJ Fam Plann Reprod Health Care2015411e125512359

- OlowookereSAAbioye-KuteyiEABamiwuyeSOFertility intentions of people living with HIV/AIDS at Osogbo, Southwest NigeriaEur J Contracept Reprod Health Care2013181616723320934

- SufaAWordofaMAWossenBADeterminants of fertility intention among women living with hiv in western Ethiopia: implications for service deliveryAfr J Reprod Health20141845460

- JoseHMadiDChowtaNFertility Desires and Intentions among People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in Southern IndiaJ Clin Diagn Res2016106OC19OC22

- GutinSANamusokeFShadeSBMirembeFFertility desires and intentions among HIV-positive women during the post-natal period in UgandaAfr J Reprod Health2014183677725438511

- DeeringKNShawSYThompsonLHFertility intentions, power relations and condom use within intimate and other non-paying partnerships of women in sex work in Bagalkot District, South IndiaAIDS Care201527101241124926295360

- FingerJLClumGATrentMEEllenJMAdolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS InterventionsDesire for pregnancy and risk behavior in young HIV-positive womenAIDS Patient Care STDS201226317318022482121

- WagnerGJWanyenzeRFertility Desires and intentions and the relationship to consistent condom use and provider communication regarding childbearing among HIV clients in UgandaISRN Infect Dis201320137

- RodriguezVJCookRRWeissSMPeltzerKJonesDLPsychosocial correlates of patient–provider family planning discussions among HIV-infected pregnant women in South AfricaOpen Access J Contracept201782528626358

- RodriguezVJLaCabeRPPrivetteCKThe Achilles’ heel of prevention to mother-to-child transmission of HIV: Protocol implementation, uptake, and sustainabilitySAHARA J2017141385228922974