Abstract

The dire conditions of the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome epidemic and the immense benefits of antiretroviral prophylaxis in prevention of mother-to-child transmission far outweigh the potential for adverse effects and undeniably justify the rapid and widespread use of this therapy, despite incomplete safety data. Highly active antiretroviral therapy has now become standard care, and more than half the validated regimens include protease inhibitors. This paper reviews current knowledge of the safety of these drugs during pregnancy, in terms of maternal and fetal outcomes. Transfer of protease inhibitors across the placenta is known to be minimal, and current data about birth defects and fetal malignancies are reassuring. Maternal liver function and glucose metabolism should be monitored in women treated with protease inhibitor-based regimens, but concerns about the development of maternal resistance, should treatment be discontinued, have been shown to be groundless. Neonates should be screened for hematologic abnormalities, although these are rarely severe or permanent and are not usually related to the protease inhibitor component of the antiretroviral combination. Current findings concerning pre-eclampsia and growth restriction are discordant, and further research is needed to address the question of placental vascular complications. The increased risk of preterm birth attributed to protease inhibitors should be interpreted with caution considering the discrepant results and the multitude of confounding factors often overlooked. Although data are thus far reassuring, further research is needed to shed light on unresolved controversies about the safety of protease inhibitors during pregnancy.

Introduction

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are substrate analogs for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) aspartyl protease enzyme, which is involved in processing viral proteins by cleaving protein molecules into smaller fragments and thus releasing mature viral particles from infected cells. Once bound to their active site, they block the enzyme from further activity, inhibit the viral maturation process, and block formation of functional virions.

PIs were the second class of antiretroviral drugs developed, and saquinavir (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was the first PI approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1995. Since then, PI-based highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens have overtaken other HAART combinations, especially in the last decade.

Tremendous progress has been achieved since the ACTG 076 trialCitation1 and introduction of antiretroviral therapy to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. The estimated annual number of newborns with HIV worldwide has dropped dramatically, falling to 330,000 in 2011,Citation2 and most of these infections occur in resource-poor countries. In developed countries where the use of HAART became widespread in the late 1990s, the transmission rate has decreased to around 1% in recent years.Citation3,Citation4

With the availability of antiretroviral drugs increasing globally, the World Health Organization has expanded its recommendations for their use. These new guidelines will drive rapid growth of antiretroviral use in resource-poor countries. Although the immense benefits of antiretroviral prophylaxis in prevention of mother-to-child transmission and the dire conditions of the HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic far outweigh the potential for adverse effects, there is now an urgent need to document better the safety of antiretroviral therapy.

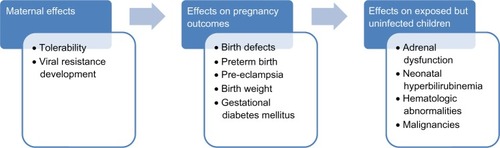

This is certainly a difficult task, especially given that the available literature on potentially rare side effects relies mainly on retrospective and cohort studies. Moreover, the great heterogeneity in populations creates major difficulties in distinguishing the side effects of different classes of antiretroviral drugs from one another and from disease complications. Discriminating class-specific effects is indeed a problem, because current HAART regimens (and thus most of the available literature) are based on combination therapies, including reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTIs). Ongoing studies comparing different single-class regimens might overcome this difficulty. In the meantime, class-specific adverse effects can reasonably be deduced from data from nonpregnant populations and the well documented effects of RTIs.Citation5 summarizes the safety concerns associated with in utero PI exposure.

Protease inhibitor regimens

Based on available data suggesting that transmission rates are similar in women with higher CD4+T cell counts regardless of whether they receive monotherapy or HAART,Citation6 the World Health OrganizationCitation7 recommends both options, without stating any preference for one over the other. However, HAART has been the standard care in high-resource countries and its use for all women is programmatically appealing. The prolonged half-life of non-nucleoside RTIs makes them less suitable as part of a short course of treatment for prevention of mother-to-child transmission only.Citation8 Triple nucleoside RTI regimens have showed similar transmission rates and better viral load suppression than PI-based HAART,Citation9 but higher rates of treatment failure in nonpregnant women have been reported when the baseline viral load is >100,000 HIV RNA copies/mL plasma.Citation10 Based on these data, the British HIV Association recommends that HAART, when indicated to prevent mother-to-child transmission, should be based on boosted PI, in the absence of specific contraindications.Citation8

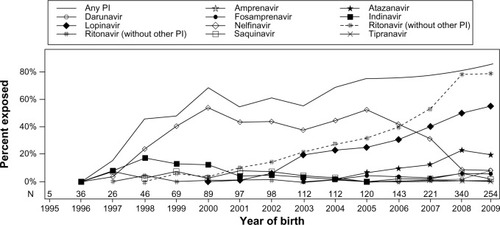

In the US, in utero exposure to PIs rose from 15% in 1997 to 86% in 2009.Citation11 It was estimated that in 2009, in northern countries, 57.6% of regimens during pregnancy were based on ritonavir-boosted PIs (Abbott, North Chicago, IL, USA),Citation12 and 79% of the children were exposed to a ritonavir-boosted PI regimen.Citation11

In 2011, Griner et alCitation11 used data from the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study Surveillance Monitoring for ART Toxicities study, a US-based prospective cohort study of HIV-exposed but uninfected children, to assess temporal trends in the use of antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. PIs were the most common class of drugs observed after triple nucleoside RTIs. The most common PI since 2007 has been lopinavir coformulated with ritonavir (Abbott). In 2009, lopinavir/ritonavir exposure was more than double that of the next most common PI, atazanavir (Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York City, NY, USA) at 55% versus 20%, respectively. Other PIs used included nelfinavir (Roche), the most common PI from 1998 to 2006, and indinavir (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), the second most common PI from 1998 to 2000. Use of amprenavir (GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK), fosamprenavir (GlaxoSmithKline), saquinavir (Roche), tipranavir (Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany), and therapeutic doses of ritonavir were also reported. Ritonavir boosting was generally common in later years (), although it varied according to the other drug.Citation11

Figure 2 Trends for in utero exposure to PI.

Abbreviation: PI, protease inhibitor.

Maternal adverse effects

Development of viral resistance

Current guidelines suggest that antiretroviral therapy should be discontinued after delivery if indicated solely for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission.Citation8 However, significant concerns remain about the possible emergence of resistance and the limitation of future therapeutic options for women receiving short-term antiretroviral therapy. A recent study addressing this question reported no clinically significant resistance 4–8 weeks post partum in 40 women receiving PI-based HAART to prevent mother-to-child transmission.Citation13 Similarly, no clinically significant drug resistance mutations were found a month after discontinuation of therapy in a subpopulation of the Mma Bana cohort.Citation14

The analysis by Briand et al of 1,116 women enrolled in the French National Agency for Research (ANRS) French Perinatal Cohort between 2005 and 2009 showed that PI-based combinations during pregnancy were not any less effective in women previously exposed to various regimens of antiretroviral prevention of mother-to-child transmission, compared with those receiving them for the first time.Citation15 On the other hand, Ellis et al observed high resistance rates among women who stopped suppressive nelfinavir-based antiretroviral therapy after pregnancy.Citation16 These results are limited by the size of the studies and the absence of data about either treatment adherence throughout pregnancy or the clinical significance of the resistance.

Considering their established immunovirologic efficacy, PI-based regimens are likely to prevent the emergence of resistance mutations. Although suboptimal therapy compliance may be partly responsible for resistance development, further studies are needed to investigate whether certain antiretroviral classes and regimens are superior to others in terms of risk of viral resistance.

Maternal tolerability

Although rarely severe, maternal adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy, mainly hepatic and hematologic, are not infrequent. Regardless of severity, better tolerability of antiretroviral regimens is crucial for improving adherence and immunovirologic efficacy. A recent study showed that the tolerability of antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy did not differ by class, but found differences between individual drugs. The PI that women found the least tolerable were nelfinavir.Citation17

Findings concerning hepatotoxicity in HIV-infected pregnant women are discordant and focus mainly on the severe side effects of nevirapine (Boehringer Ingelheim).Citation18–Citation20 High-dose ritonavir (1,200 mg/day) has been associated with an increased risk of hepatotoxicity compared with other antiretroviral regimens.Citation21 However, high-dose ritonavir is no longer used as first-line treatment. Instead, because it is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A4 metabolism, it is increasingly coadministered with other PIs, such as lopinavir, saquinavir, and indinavir, at a very low dose to improve bioavailability and prolong the elimination half-life of these drugs. This strategy makes dosing schedules easier to comply with and enhances efficacy.

In a cohort of nonpregnant patients reported by Sulkowski et al, grade 3 or 4 liver enzyme elevations were observed in 12% of patients starting their first PI-based antiretroviral therapy. Lopinavir/ritonavir was not associated with a significantly higher risk of hepatotoxicity compared with a nelfinavir-based regimen.Citation22 Given our insufficient knowledge of the mechanisms of hepatotoxicity and in the absence of reassuring data, the role of PIs in this finding cannot be ruled out, and liver function should be monitored. Furthermore, it is often difficult to distinguish antiretroviral liver toxicity from pregnancy-related liver disorders.

Atazanavir use is also associated with an increased risk of elevated serum bilirubin as a result of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase 1A1 inhibition,Citation23,Citation24 which has also been reported, albeit to a lesser extent, with indinavir.Citation25 Concerns have also been raised about an increased risk of kidney stones in patients receiving atazanavir, especially if associated with tenofovir.Citation26

Pregnancy outcomes

Birth defects

Due to their high degree of plasma protein binding and their backward transport through P-glycoprotein, placental transfer of PIs is minimal or absent, although the level may differ according to the specific substance (). These findings have been confirmed by studies using an ex vivo placental perfusion model for lopinavir.Citation27,Citation28 Other ex vivo studies have showed that the clearance index is lowest for saquinavir,Citation29 low for ritonavir,Citation30 and higher for amprenavir.Citation31 Likewise, in vivo studies have confirmed the minimal placental transfer of PIs,Citation32–Citation34 except for atazanavir, which has been shown to cross the placenta.Citation35

Table 1 Safety classification and placental transfer of PIs for use in pregnancy

Available data on teratogenicity has been gathered from various sources, including animal studies, therapeutic trials, cohort and surveillance studies, and the US Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry. This registry was established in 1989 to collect data on birth defects after pregnancy exposures to antiretroviral therapy and conforms to FDA guidelines for pregnancy exposure registries. Its data can be considered robust and reliable.

Registry data indicate that the prevalence of birth defects for first trimester and overall prenatal exposure to lopinavir/ritonavir is similar to the population-based comparator rate of 2.67%.Citation36 No pattern of birth defects suggestive of a common etiology has been seen.Citation36 Similarly, according to a study funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb, the prevalence of birth defects for exposure to atazanavir during the first and the second/third trimester, as well as overall exposure, does not differ from the general population rate for birth defects.Citation37

However, the current absence of a statistically significant association between PI exposure and a higher birth defect prevalence should be interpreted cautiously. Because these outcomes are rare, the reassuring data might result simply from the limited sample size. Given that the currently used PIs are in either FDA pregnancy category B or C (), monitoring the potential teratogenic effects of these drugs remains necessary.

Preterm birth

Although numerous studies have addressed the question of a potential association between PI-based HAART and preterm birth, it remains controversial. Since the first European study brought this issue to light in 2000, several others, emphasizing the role of PIs and early onset of therapy, have confirmed the risk.Citation38–Citation40 It has been hypothesized that the physiopathology of preterm birth in the context of PI-based HAART involves immune reconstitution with cytokine shifts that induce the premature onset of labor, rather than any fetal or uteroplacental cause.Citation41,Citation42 This mechanism might explain why the risk of preterm birth is highest when therapy onset is earliest. Another potential pathway is the impact on the maternal and fetal adrenal axes involved in spontaneous preterm delivery through disruption of the glucocorticoid metabolism induced by ritonavir-associated inhibition of cytochrome P450 2A4.Citation43

Another particularity of HAART regimens including PIs is that they were initially a preferential treatment for women with more advanced HIV disease, which in itself is a risk factor for preterm birth. This confounding element might thus account for (some of) the increased risk of prematurity observed in this group.

Studies addressing this problem of confounding by indication have reported no association between preterm birth and PI regimens,Citation44 not even with early exposure to therapy.Citation45,Citation46 More recently a study based on the ANRS French Perinatal Cohort implicated ritonavir boosting. After adjusting for immunovirologic status and known risk factors, Sibiude et al showed that ritonavir-boosted PIs are associated with a higher risk of induced preterm birth and of maternal metabolic and vascular complications, compared with non-boosted PIs. No causal relation was established, but immune restoration cannot entirely explain this effect on induced preterm birth.Citation47

Evidently an answer to this question requires more data. Two randomized trials in limited-resource countries have taken important steps in this direction. The Kesho Bora studyCitation6 randomized 882 HIV-infected women with CD4+ T cell counts of 200–500 cells/mm3 to a PI-based regimen versus zidovudine with a single dose nevirapine at the onset of labor. Antiretroviral therapies (except for a single dose of nevirapine) began between 28 and 36 weeks of gestation. Preterm birth rates did not differ between the two groups. These results, however, were contradicted by those of the Mma Bana trial, which randomized 560 women with CD4+ T cell counts ≥200 cells/mm3 to a PI-based regimen versus a triple nucleoside RTI regimen, both started during the third trimester of gestation. This study reported a higher risk of preterm birth in the PI group, but no increase in rates of infant hospitalization or mortality.Citation48 The later start of HAART in the Kesho Bora study might explain this discrepancy.

Given the conflicting findings of the current studies, it is too early to rush into recommendations without validation from further research. It is currently estimated that for every 100 HIV transmissions prevented with HAART, rather than monotherapy, 63 additional preterm births occur, including 23 before 32 weeks of gestation.Citation49 Interpretation of these findings requires additional information about the morbidity, mortality, and costs associated with these outcomes. Larger multisite international studies could shed further light on this important question.

Birth weight

Observational studies of varying levels of evidence report discordant data about the potential effect of PI-based regimens on birth weight. These discrepancies might be partly explained by the failure to discriminate between infants who are small-for-gestational age (SGA) and those with a low birth weight attributable to preterm birth.

Some authors report statistically significant SGA associated with HAART use (with or without PIs).Citation50–Citation52 Furthermore, in 2011, Parekh et al described an association between prepregnancy HAART continued throughout pregnancy (without specifying PI use) and very SGA neonates (less than the third percentile).Citation53

None of these studies implicated PIs directly, and more specific studies have reported no association between PI-based regimens and SGA.Citation40,Citation54,Citation55 Likewise, the randomized Kesho Bora trial showed no significant increase in low (<2,500 g) or very low (<1,500 g) birth weights in the PI-based HAART arm.Citation6 The results from the ANRS French Perinatal cohort also suggest that HAART during pregnancy does not increase the incidence of SGA infants.Citation56

In 2009, Ivanovic et al reported that birth weight <2,500 g is associated with the ratio of antiretroviral drug concentrations in maternal and cord plasma.Citation57 In view of both this pharmacologic rationale and the low transplacental transfer of PIs (which implies low cord-to-maternal plasma ratios), an association between low birth weight and PI-based regimens seems unlikely. These results suggest that PIs are not specifically associated with increased SGA, but this needs to be confirmed by further research.

Pre-eclampsia

The etiology of pre-eclampsia is multifactorial but the role of the immune system as a causal factor is now well established. Immune modifications induced by HIV might thus intervene in the development of pre-eclampsia. The significantly lower incidence of pre-eclampsia reported in untreated HIV-infected patients than in women treated with HAART led to the suggestion that the immune deficiency induced by HIV infection could prevent the development of pre-eclampsia, but that this “benefit” is lost with treatment.Citation58 Other authors have proposed that HAART causes pre-eclampsia by a direct toxic effect on the liver that impairs the synthesis and secretion of retinol-binding proteins and leads to the reduced serum retinol concentrations that have been associated with pre-eclampsia.Citation59

Since then, contradictory data about this association have been reported. An adequately powered South African study showed no reduction in the risk of pre-eclampsia in untreated HIV patients,Citation60 and a prospective Brazilian study reported a significantly lower rate of pre-eclampsia among treated (HAART or monotherapy) HIV-infected women compared with uninfected controls.Citation61

In contrast, Suy et al reported in 2006 that HIV infection treated with HAART before pregnancy was associated with a significantly higher risk of pre-eclampsia and fetal death and that this risk did not return to baseline with therapy, but actually increased. The relevance of these results is limited by the fact that odd ratios were not adjusted for baseline risk factors such as chronic hypertension or diabetes mellitus.Citation62 More recently, two North American studies found no increase in the pre-eclampsia rates among treated HIV-infected women, regardless of the type of therapy.Citation54,Citation63

These discrepancies may be related to differences in the study populations and their underlying medical morbidities. Nonetheless, the inconsistency of the available results leaves immense uncertainty as to whether HIV lowers or increases the rate of pre-eclampsia and how antiretroviral therapy affects this rate. Further research is needed to answer this question, which might be addressed as a physiopathologic entity conjointly with other placental vascular complications, such as growth restriction.

Gestational diabetes mellitus

PIs have been associated with glucose and lipid metabolism abnormalities in nonpregnant populations, even in the absence of HIV infection. Several studies have demonstrated intraclass differences in the effect of PIs on glucose metabolism.Citation64–Citation66 Analysis of the PACTG 316 study revealed an increased risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in women receiving PI-based HAART before or early in pregnancy.Citation67 Prospective studies have reported similar results.Citation68,Citation69 However, other authors have found no association between PI use and glucose intolerance in either retrospective studiesCitation45,Citation70 or larger prospective trials.Citation71

It is thus too early to reach conclusions, and further investigations are needed to assess the association between PIs and gestational diabetes mellitus. In the meantime, pregnant women receiving PI regimens should be screened for gestational diabetes mellitus and monitored closely during pregnancy. On the other hand, in animal models, fetal and maternal exposure to lopinavir is reduced in subjects with gestational diabetes mellitus. If confirmed in humans, this drug-disease interaction reducing the bioavailability of lopinavir would have to be taken into account and exposure targets monitored carefully in women with gestational diabetes mellitus.Citation72

Uninfected children

Malignancies

Animal studies have found some antiretroviral drugs to be genotoxic,Citation73,Citation74 thus raising concerns about the carcinogenic potential of perinatal exposure to such therapy. Initial results from cohorts of antiretroviral-exposed children report a reassuring lack of malignancies.Citation75 Although no current evidence suggests an increased risk of childhood malignancies, this risk cannot be ruled out, especially given that most of the published studies have investigated the relatively short-term effects of zidovudine. Longer follow-up of exposed and uninfected children until adulthood is needed, but might be very challenging. Collecting information by cross-checking databases is feasible and would be most valuable. Although adequate data discriminating between drug classes are unavailable, PIs appear unlikely to be carcinogenic; indeed, animal studies report nelfinavir, among other PIs, to have anticarcinogenic properties.Citation57,Citation76,Citation77

Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia

Atazanavir is the second most commonly used PI during pregnancy.Citation11 It is known to cause serum bilirubin to rise by inhibiting uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A1,Citation23,Citation24 which indinavir also does, albeit to a lesser extent.Citation25 Atazanavir use during pregnancy might therefore exacerbate physiologic hyperbilirubinemia in neonates and thus create the risk of severe neurologic impairment. Recent studies report elevated serum bilirubin in neonates born to mothers treated with atazanavir.Citation78,Citation79 Whether this neonatal hyperbilirubinemia is due to placental transfer of unconjugated bilirubin from the mother or to the direct effect of transplacental atazanavir on fetal bilirubin metabolism is uncertain, but the cases reported were rarely clinically significant and never severe. These results are consistent with current guidelines, ie, atazanavir is now a preferred PI, which can be continued or initiated during pregnancy, but its use mandates close monitoring of bilirubin levels in mothers and their babies.Citation9

Hematologic abnormalities

A number of studies have reported subclinical hematologic abnormalities in uninfected infants exposed to both HIV and antiretroviral drugs.Citation80–Citation82 The duration of follow-up in these studies has varied, but generally anemia has seemed to be transient, whereas neutropenia and lymphopenia have been more prolonged.Citation83 These abnormalities appear to be negatively related to the duration of exposure, and in utero exposure to combination treatment, compared with monotherapy, was associated with greater depletion than monotherapy.Citation52,Citation54 Combination antiretroviral therapy contained a PI in 19% of cases,Citation52 although the analysis did not consider the composition of the combination.

The clinical significance of these findings is unclear, but further monitoring of antiretroviral therapy-related hematopoietic effects is needed. Complementary research is needed to determine the mechanisms of these effects and whether they are class-dependent.

Adrenal dysfunction

A recent retrospective cross-sectional analysis of the database from the French national screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia and the ANRS French Perinatal Cohort shows that newborns exposed in utero to lopinavir/ritonavir and receiving it as a postnatal treatment were more likely than those receiving zidovudine to have transient adrenal dysfunction with increased 17-OH progesterone levels.Citation84 Further studies are needed to test the hypothesis of whether lopinavir/ritonavir acts as an inhibitor of adrenal steroid synthesis in fetuses and newborns.

Conclusion

This review regarding the adverse effects of PIs during pregnancy highlights the many areas in which discrepancies exist or data are lacking. We must acknowledge that this is a synthetic and not systematic review, and does not apply the specific methodology for systematic reviews or meta-analyses. The increasing exposure to antiretroviral therapy including HAART, in resource-poor countries, calls for a thorough assessment. In these settings, large randomized prospective trials have shed light upon such disputed questions as growth restriction and preterm birth.Citation20,Citation21 Such trials might be the key to improving our knowledge of the safety of antiretroviral drugs, as their power and design might make it possible to discriminate class-related adverse effects, which are a major concern. This issue was appropriately addressed in the French ANRS 135 PRIMEVA trial, the preliminary results of which were presented at the 2011 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.Citation85 In this Phase II/III multicenter trial performed in France, untreated pregnant women with a baseline viral load <30,000 copies/mL and CD4+ T ≥350 cells/μL were randomized to receive one of two possible treatments from 26 weeks of gestation to delivery: open-label lopinavir/ritonavir 400/100 mg twice daily alone (monotherapy group, n = 69) or combined with zidovudine/lamivudine 300/150 mg twice daily (triple therapy group, n = 36). The ongoing analyses within this trial to evaluate the potential benefits of nucleoside-sparing in terms of toxicity could help to isolate the specific effects of PIs.

Assessing the safety of PIs and antiretroviral drugs in general needs further and longer-term monitoring. Because such adverse effects are likely to be rare and might occur later in childhood establishing registries in resource-poor countries and maintaining participation in existing ones is crucial. At this time, based on what we now know, the benefits of PI-based HAART regimens far outweigh the potential side effects. Most PIs can be considered safe for use during pregnancy, although precautions need to be taken with certain patients and newer substances.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ConnorEMSperlingRSGelberRReduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study GroupN Engl J Med199433118117311807935654

- GhanotakisEMillerLSpensleyACountry adaptation of the 2010 World Health Organization recommendations for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIVBull World Health Organ2012901292193123284198

- MandelbrotLLandreau-MascaroARekacewiczCLamivudine-zidovudine combination for prevention of maternal-infant transmission of HIV-1JAMA2001285162083209311311097

- TownsendCLCortina-BorjaMPeckhamCSTookeyPATrends in management and outcome of pregnancies in HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland, 1990–2006BJOG200811591078108618503577

- ThorneCNewellMLSafety of agents used to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV: is there any cause for concern??Drug Saf200730320321317343429

- Kesho Bora StudyGde VincenziITriple antiretroviral compared with zidovudine and single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (Kesho Bora study): a randomised controlled trialLancet Infect Dis201111317118021237718

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Monitoring Framework and Strategy for the Global Plan Towards the Elimination of new HIV infections Among Children by 2015 and Keeping Their Mothers Alive (EMTCT) GenevaSwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2012

- TaylorGPClaydenPDharJBritish HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV infection in pregnant women 2012HIV Med201213Suppl 28715722830373

- ShapiroRLHughesMDOgwuAAntiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in BotswanaN Engl J Med2010362242282229420554983

- WilliamsIChurchillDAndersonJBritish HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2012HIV Med201213Suppl 2185

- GrinerRWilliamsPLReadJSIn utero and postnatal exposure to antiretrovirals among HIV-exposed but uninfected children in the United StatesAIDS Patient Care STDS201125738539421992592

- BaroncelliSTamburriniERavizzaMAntiretroviral treatment in pregnancy: a six-year perspective on recent trends in prescription patterns, viral load suppression, and pregnancy outcomesAIDS Patient Care STDS200923751352019530956

- GingelmaierAEberleJKostBPProtease inhibitor-based antiretroviral prophylaxis during pregnancy and the development of drug resistanceClin Infect Dis201050689089420166821

- SoudaSGaseitsiweSGeorgetteNNo clinically significant drug resistance mutations in HIV-1 subtype C infected women after discontinuation of NRTI-based or PI-based HAART for PMTCT In BotswanaJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr3282013 [Epub ahead of print.]

- BriandNMandelbrotLBlancheSPrevious antiretroviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV does not hamper the initial response to PI-based multitherapy during subsequent pregnancyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201157212613521436712

- EllisGMHuangSHittiJFrenkelLMTeamPSSelection of HIV resistance associated with antiretroviral therapy initiated due to pregnancy and suspended postpartumJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201158324124721765365

- WeinbergAForster-HarwoodJDaviesJSafety and tolerability of antiretrovirals during pregnancyInfect Dis Obst Gynecol2011201186767421603231

- OuyangDWBroglySBLuMLack of increased hepatotoxicity in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving nevirapine compared with other antiretroviralsAIDS201024110911419926957

- LyonsFHopkinsSKelleherBMaternal hepatotoxicity with nevirapine as part of combination antiretroviral therapy in pregnancyHIV Med20067425526016630038

- HittiJFrenkelLMStekAMMaternal toxicity with continuous nevirapine in pregnancy: results from PACTG 1022J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200436377277615213559

- GisolfEHDreezenCDannerSAWeelJLWeverlingGJPrometheus Study GroupRisk factors for hepatotoxicity in HIV-1-infected patients receiving ritonavir and saquinavir with or without stavudine. Prometheus Study GroupClin Infect Dis20003151234123911073757

- SulkowskiMSMehtaSHChaissonREThomasDLMooreRDHepatotoxicity associated with protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral regimens with or without concurrent ritonavirAIDS200418172277228415577540

- TortiCLapadulaGAntinoriAHyperbilirubinemia during atazanavir treatment in 2,404 patients in the Italian atazanavir expanded access program and MASTER CohortsInfection200937324424919471856

- ZhangDChandoTJEverettDWPattenCJDehalSSHumphreysWGIn vitro inhibition of UDP glucuronosyltransferases by atazanavir and other HIV protease inhibitors and the relationship of this property to in vivo bilirubin glucuronidationDrug Metab Dispos200533111729173916118329

- RaynerCREschLDWynnHEEalesRSymptomatic hyperbilirubinemia with indinavir/ritonavir-containing regimenAnn Pharmacother200135111391139511724090

- HamadaYNishijimaTWatanabeKHigh incidence of renal stones among HIV-infected patients on ritonavir-boosted atazanavir than in those receiving other protease inhibitor-containing antiretroviral therapyClin Infect Dis20125591262126922820542

- GavardLGilSPeytavinGPlacental transfer of lopinavir/ritonavir in the ex vivo human cotyledon perfusion modelAm J Obstet Gynecol2006195129630116678781

- CeccaldiPFGavardLMandelbrotLFunctional role of p-glycoprotein and binding protein effect on the placental transfer of lopinavir/ritonavir in the ex vivo human perfusion modelObstet Gynecol Int2009200972659319960055

- ForestierFde RentyPPeytavinGDohinEFarinottiRMandelbrotLMaternal-fetal transfer of saquinavir studied in the ex vivo placental perfusion modelAm J Obstet Gynecol2001185117818111483925

- CaseyBMBawdonREPlacental transfer of ritonavir with zidovudine in the ex vivo placental perfusion modelAm J Obstet Gynecol19981793 Pt 17587619757985

- BawdonREThe ex vivo human placental transfer of the anti-HIV nucleoside inhibitor abacavir and the protease inhibitor amprenavirInfect Dis Obstet Gynecol1998662442469972485

- MarzoliniCRudinCDecosterdLATransplacental passage of protease inhibitors at deliveryAIDS200216688989311919490

- MirochnickMDorenbaumAHollandDConcentrations of protease inhibitors in cord blood after in utero exposurePediatr Infect Dis J200221983583812352805

- ChappuyHTreluyerJMReyEMaternal-fetal transfer and amniotic fluid accumulation of protease inhibitors in pregnant women who are infected with human immunodeficiency virusAm J Obstet Gynecol2004191255856215343237

- RipamontiDCattaneoDMaggioloFAtazanavir plus low-dose ritonavir in pregnancy: pharmacokinetics and placental transferAIDS200721182409241518025877

- RobertsSSMartinezMCovingtonDLRodeRAPasleyMVWoodwardWCLopinavir/ritonavir in pregnancyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200951445646119381099

- EskerSAlbanoJUyJMonitoring the risk of birth defects associated with atazanavir exposure in pregnancyAIDS Patient Care STDS201226630731122404239

- CotterAMGarciaAGDuthelyMLLukeBO’SullivanMJIs antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, or stillbirth? J Infect Dis200619391195120116586354

- KourtisAPSchmidCHJamiesonDJLauJUse of antiretroviral therapy in pregnant HIV-infected women and the risk of premature delivery: a meta-analysisAIDS200721560761517314523

- WattsDHWilliamsPLKacanekDCombination antiretroviral use and preterm birthJ Infect Dis2013207461262123204173

- FioreSFerrazziENewellMLTrabattoniDClericiMProtease inhibitor-associated increased risk of preterm delivery is an immunological complication of therapyJ Infect Dis2007195691491617299724

- Grosch-WoernerIPuchKMaierRFIncreased rate of prematurity associated with antenatal antiretroviral therapy in a German/Austrian cohort of HIV-1-infected womenHIV Med20089161318199167

- YanovskiJAMillerKDKinoTEndocrine and metabolic evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with evidence of protease inhibitor-associated lipodystrophyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19998461925193110372688

- CheshireMKingstonMMcQuillanOGittinsMAre HIV-related factors associated with pre-term delivery in a UK inner city setting? J Int AIDS Soc201215618223

- AzriaEMoutafoffCSchmitzTPregnancy outcomes in women with HIV type-1 receiving a lopinavir/ritonavir-containing regimenAntivir Ther200914342343219474476

- PatelKShapiroDEBroglySBPrenatal protease inhibitor use and risk of preterm birth among HIV-infected women initiating antiretroviral drugs during pregnancyJ Infect Dis201020171035104420196654

- SibiudeJWarszawskiJTubianaRPremature delivery in HIV-infected women starting protease inhibitor therapy during pregnancy: role of the ritonavir boost? Clin Infect Dis20125491348136022460969

- PowisKMKitchDOgwuAIncreased risk of preterm delivery among HIV-infected women randomized to protease versus nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HAART during pregnancyJ Infect Dis2011204450651421791651

- TownsendCLTookeyPANewellMLCortina-BorjaMAntiretroviral therapy in pregnancy: balancing the risk of preterm delivery with prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmissionAntivir Ther201015577578320710059

- TownsendCLCortina-BorjaMPeckhamCSTookeyPAAntiretroviral therapy and premature delivery in diagnosed HIV-infected women in the United Kingdom and IrelandAIDS20072181019102617457096

- ShapiroRLRibaudoHPowisKChenJParekhNExtended antenatal use of triple antiretroviral therapy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 correlates with favorable pregnancy outcomesAIDS201226112012122126816

- ChenJYRibaudoHJSoudaSHighly active antiretroviral therapy and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-infected women in BotswanaJ Infect Dis2012206111695170523066160

- ParekhNRibaudoHSoudaSRisk factors for very preterm delivery and delivery of very-small-for-gestational-age infants among HIV-exposed and HIV-unexposed infants in BotswanaInt J Gynaecol Obstet20111151202521767835

- HaeriSShauerMDaleMObstetric and newborn infant outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women who receive highly active antiretroviral therapyAm J Obstet Gynecol20092013315e311e31519733286

- DolaCPKhanRDeNicolaNCombination antiretroviral therapy with protease inhibitors in HIV-infected pregnancyJ Perinat Med2011401515522044007

- BriandNMandelbrotLLe ChenadecJNo relation between in-utero exposure to HAART and intrauterine growth retardationAIDS200923101235124319424054

- IvanovicJNicastriEAnceschiMMTransplacental transfer of antiretroviral drugs and newborn birth weight in HIV-infected pregnant womenCurrent HIV Res200976620625

- WimalasunderaRCLarbalestierNSmithJHPre-eclampsia, antiretroviral therapy, and immune reconstitutionLancet200236093401152115412387967

- MawsonAREffects of antiretroviral therapy on occurrence of pre-eclampsiaLancet2003361935434734812559889

- FrankKABuchmannEJSchackisRCDoes human immunodeficiency virus infection protect against pre-eclampsia-eclampsia?Obstet Gynecol2004104223824215291993

- MattarRAmedAMLindseyPCSassNDaherSPre-eclampsia and HIV infectionEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2004117224024115541864

- SuyAMartinezECollOIncreased risk of pre-eclampsia and fetal death in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapyAIDS2006201596616327320

- BoyajianTShahPSMurphyKERisk of pre-eclampsia in HIV-positive pregnant women receiving HAART: a matched cohort studyJ Obstet Gynaecol Can201234213614122340062

- NoorMAParkerRAO’MaraEThe effects of HIV protease inhibitors atazanavir and lopinavir/ritonavir on insulin sensitivity in HIV-seronegative healthy adultsAIDS200418162137214415577646

- NoorMAFlintOPMaaJFParkerRAEffects of atazanavir/ritonavir and lopinavir/ritonavir on glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity: demonstrable differences in vitro and clinicallyAIDS200620141813182116954722

- NoorMAThe role of protease inhibitors in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated insulin resistance: cellular mechanisms and clinical implicationsCurr HIV/AIDS Rep20074312613417883998

- WattsDHBalasubramanianRMaupinRTJrMaternal toxicity and pregnancy complications in human immunodeficiency virus-infected women receiving antiretroviral therapy: PACTG 316Am J Obstet Gynecol2004190250651614981398

- El BeitunePDuarteGFossMCEffect of antiretroviral agents on carbohydrate metabolism in HIV-1 infected pregnant womenDiabetes Metab Res Rev2006221596316021650

- Gonzalez-TomeMIRamos AmadorJTGuillenSGestational diabetes mellitus in a cohort of HIV-1 infected womenHIV Med200891086887418983478

- TangJHSheffieldJSGrimesJEffect of protease inhibitor therapy on glucose intolerance in pregnancyObstet Gynecol200610751115111916648418

- HittiJAndersenJMcComseyGProtease inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy and glucose tolerance in pregnancy: AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5084Am J Obstet Gynecol20071964331e331e33717403409

- AngerGJPiquette-MillerMMechanisms of reduced maternal and fetal lopinavir exposure in a rat model of gestational diabetesDrug Metab Dispos201139101850185921742899

- OliveroOAFernandezJJAntiochosBBWagnerJLSt ClaireMEPoirierMCTransplacental genotoxicity of combined antiretroviral nucleoside analogue therapy in Erythrocebus patas monkeysJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200229432332911917235

- OliveroOARelevance of experimental models for investigation of genotoxicity induced by antiretroviral therapy during human pregnancyMutat Res2008658318419018295533

- European Collaborative StudyExposure to antiretroviral therapy in utero or early life: the health of uninfected children born to HIV-infected womenJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200332438038712640195

- GillsJJLopiccoloJTsurutaniJNelfinavir, a lead HIV protease inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum, anticancer agent that induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in vitro and in vivoClin Cancer Res200713175183519417785575

- GillsJJLopiccoloJDennisPANelfinavir, a new anti-cancer drug with pleiotropic effects and many paths to autophagyAutophagy20084110710918000394

- MandelbrotLMazyFFloch-TudalCAtazanavir in pregnancy: impact on neonatal hyperbilirubinemiaEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol20111571182121492993

- ConradieFZorrillaCJosipovicDSafety and exposure of once-daily ritonavir-boosted atazanavir in HIV-infected pregnant womenHIV Med201112957057921569187

- Le ChenadecJMayauxMJGuihenneuc-JouyauxCBlancheSEnquete Perinatale Francaise Study GroupPerinatal antiretroviral treatment and hematopoiesis in HIV-uninfected infantsAIDS200317142053206114502008

- European Collaborative StudyLevels and patterns of neutrophil cell counts over the first 8 years of life in children of HIV-1-infected mothersAIDS200418152009201715577622

- Feiterna-SperlingCWeizsaeckerKBuhrerCHematologic effects of maternal antiretroviral therapy and transmission prophylaxis in HIV-1-exposed uninfected newborn infantsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2007451435117356471

- HeidariSMofensonLCottonMFMarlinkRCahnPKatabiraEAntiretroviral drugs for preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a review of potential effects on HIV-exposed but uninfected childrenJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201157429029621602695

- SimonAWarszawskiJKariyawasamDAssociation of prenatal and postnatal exposure to lopinavir-ritonavir and adrenal dysfunction among uninfected infants of HIV-infected mothersJAMA20113061707821730243

- TubianaRMandelbrotLDelmasSthe Primeva Study GroupLPV/r monotherapy during pregnancy for PMTCT of HIV-1: the PRIMEVA/ANRS 135 randomized trial, pregnancy outcomesPaper presented at the 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic InfectionsBoston, MAFebruary 27 to March 2, 2011