Abstract

Microbicides, primarily used as topical pre-exposure prophylaxis, have been proposed to prevent sexual transmission of HIV. This review covers the trends and challenges in the development of safe and effective microbicides to prevent sexual transmission of HIV Initial phases of microbicide development used such surfactants as nonoxynol-9 (N-9), C13G, and sodium lauryl sulfate, aiming to inactivate the virus. Clinical trials of microbicides based on N-9 and C31G failed to inhibit sexual transmission of HIV. On the contrary, N-9 enhanced susceptibility to sexual transmission of HIV-1. Subsequently, microbicides based on polyanions and a variety of other compounds that inhibit the binding, fusion, or entry of virus to the host cells were evaluated for their efficacy in different clinical setups. Most of these trials failed to show either safety or efficacy for prevention of HIV transmission. The next phase of microbicide development involved antiretroviral drugs. Microbicide in the form of 1% tenofovir vaginal gel when tested in a Phase IIb trial (CAPRISA 004) in a coitally dependent manner revealed that tenofovir gel users were 39% less likely to become HIV-infected compared to placebo control. However, in another trial (VOICE MTN 003), tenofovir gel used once daily in a coitally independent mode failed to show any efficacy to prevent HIV infection. Tenofovir gel is currently in a Phase III safety and efficacy trial in South Africa (FACTS 001) employing a coitally dependent dosing regimen. Further, long-acting microbicide-delivery systems (vaginal ring) for slow release of such antiretroviral drugs as dapivirine are also undergoing clinical trials. Discovering new markers as correlates of protective efficacy, novel long-acting delivery systems with improved adherence in the use of microbicides, discovering new compounds effective against a broad spectrum of HIV strains, developing multipurpose technologies incorporating additional features of efficacy against other sexually transmitted infections, and contraception will help in moving the field of microbicide development forward.

Introduction

AIDS is an immunological disorder characterized by abnormalities of immunoregulation and opportunistic infections caused by HIV. At the end of 2010, there were an estimated 34 million people living with HIV infection across the world, and approximately 1.8 million people died from HIV/AIDS in the year 2010.Citation1 Approximately 2.6 million new infections were reported during the same year. In Africa, AIDS remains the main cause of death. Sub-Saharan Africa is most rigorously affected, with over 22.5 million people living with HIV/AIDS. In Asia, an estimated 4.9 million people were living with HIV infection in the year 2009. According to a Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS 2011 update, the overall growth of the global AIDS epidemic appears to have stabilized, and the number of new infections has been falling. However, the overall level of new infections is still high, and with signifi-cant reduction in mortality, the number of people living with HIV infection worldwide has increased.Citation1

In the majority of cases, HIV infection occurs through homo- or heterosexual routes; however, the transmission of HIV from infected mother to child and through blood transfusion is also on the rise. “Safe sex” has been proposed as one of the major approaches to prevent sexual transmission of HIV. The use of male condoms greatly reduces the chances of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV infection, and in addition provides protection against conception. However, the usage of condoms by males is very low, as its use is perceived to reduce sexual pleasure. Female condoms have been developed to overcome this problem. Due to objections from the male partners and higher cost, their use is many times lower than male condoms.Citation2 Currently, highly active antiretroviral (HAART) drugs belonging to four general categories – nucleoside/nucleotide viral reverse-transcriptase (RT) inhibitors (NRTIs), nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors, and fusion (or entry) inhibitors – are the mainstream drugs to prevent and cure HIV infection.Citation3 Usage of HAART drugs as a treatment option for HIV infection has expanded during the past few years.Citation4 Treatment with a HAART triple-drug cocktail of two nucleoside inhibitors and one protease inhibitor can reduce the blood virus load below the detectable level (<50 copies of viral RNA/mL of plasma) in HIV-infected patients.Citation5 Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) using a combination of two drugs, namely emtricitabine and tenofovir (TFV) disoproxil fumarate (TDF), showed an estimated efficacy of 44% against HIV infection in men who had sex with men, which is quite encouraging.Citation6 Long-term usage of available antiretroviral drugs leads to the issue of drug resistance and severe side effects, such as diarrhea, nausea, lipodystrophy, hyperglycemia, liver toxicity, pancreatitis, and neuropathy.Citation4,Citation7,Citation8

To prevent HIV infections, attempts are also being made to develop vaccines, which are at different stages of development and clinical trials. Several vaccines using a variety of vectors, such as canarypox, adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5), adeno-associated virus, and modified vaccinia virus Ankara strain, incorporating varieties of HIV proteins, aiming to generate either neutralizing antibodies or HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells, have been evaluated in humans without significant success.Citation9–Citation13 DNA vaccines against HIV have also been proposed, primarily as a prime-boost strategy, whereby priming is done with DNA vaccine followed by a vector-based vaccine. An alternate prime-boost strategy also comprises priming with live vector-based vaccine followed by booster with recombinant protein subunit vaccine. The RV144 vaccine, a combination of two genetically engineered vaccines (a “prime” vaccine called ALVAC-HIV [CCP1521] with a boost of the AIDSVAX gp120 vaccine, an envelope-protein segment from HIV subtypes B and E), showed protective efficacy of 31.2% when tested on more than 16,000 human volunteers in Thailand.Citation14 The recent discontinuation of HVTN505 clinical trials by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is a setback to the area of vaccine development. This vaccine comprised of priming with DNA vaccine followed by booster with Ad5-expressing surface and structural proteins of three major HIV clades. The vaccine regimen neither prevented HIV infection compared to the placebo group nor reduced the viral load. Since neutralizing antibodies have provided the best correlate of vaccine efficacy, it is imperative to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies. As estimated, 10%–25% of HIV-infected individuals develop broadly neu-tralizing antibodies and monoclonal antibodies from these subjects have been successfully developed.Citation15 Attempts to develop vaccines incorporating multiple epitopes recognized by broadly neutralizing antibodies are under way, with the aim to have better efficacy against HIV infection.Citation16,Citation17 Keeping in view that a vaccine for prevention of HIV infection with proven efficacy is still awaited, it is imperative to explore alternate prophylactic and therapeutic options.

Microbicides for prevention of HIV

To prevent homo- or heterosexual transmission of HIV, microbicides have been proposed. Microbicides are formulations that can be applied topically to the vagina or rectum for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV or other pathogens.Citation18 Microbicides can be formulated as semisolid gel, cream, vaginal film, or tablet. Topical microbicides can provide excellent potential for a female-controlled, preventive option, which would not require negotiation, consent, or even knowledge of the partner. Both women and men would benefit, as these can be bidirectional.Citation19 Microbicides will also be very useful for prevention of HIV infection in those cases that have multiple sex partners.

An ideal microbicide should effectively inhibit transmission of pathogens causing STIs while resulting in minimal disruption to the structural integrity and function of the healthy cervicovaginal epithelium without inhibiting vaginal Lactobacillus, the most prevalent component of the reproductive tract’s dynamic ecosystem. These beneficial bacteria help protect the vagina from pathogenic microbes.Citation20 An ideal microbicide should be:

Safe: it should preserve the natural anatomy of the female reproductive tract (does not lead to lesion and aberration in epithelial layer), produce no proinflammatory response, and protect the natural vaginal microecological system, including lactobacilli

Acceptable: applicable hours before sex; not messy or ‘leaky’; rapid and even-spreading properties; long-acting; not smelly and taste OK

Effective against HIV and a wide range of pathogens causing STIs, eg, Trichomonas vaginalis, Neisseria gon-orrhoeae, Treponema pallidum, Chlamydia trachomatis, and herpes simplex virus (HSV).

Such a microbicide would lead to the empowerment of susceptible receptive partners to adopt an independent and effective measure for their own protection without the other partner’s consent or knowledge compared to the usage of condoms. In the direction of multipurpose technologies (MPTs), attempts are also being made to develop microbicides with an added component of contraceptive efficacy. This review provides an update on clinical usage of vaginal or rectally applied microbi-cides and identifies the critical challenges to their progress.

Mechanism of action of microbicides

Advances made in our understanding of the basic biology of HIV and its transmission has led to the development of microbicides aiming to interfere at different stages of the virus life cycle. HIV infects vital cells of the human immune system, such as T helper cells (specifically CD4+ T cells), macrophages, and dendritic cells. HIV entry into the host cell is initiated by the binding of the envelope protein gp120 to a set of molecules present over the host cell surface, comprising the primary receptor CD4 and a coreceptor, usually either CCR5 or CXCR4.Citation21–Citation23 HIV preferentially uses CCR5 during the acute phase of infection, but switches to CXCR4 later as the disease progresses in approximately 50% of patients.Citation24 After the initial binding of gp120 with the CD4 receptor present on the target cells, it is further stabilized by the heparan sulfate proteoglycans present on the host cell surface. This binding induces a conformational change in the gp120, exposing sites that interact with the chemokine receptor (CCR5 or CXCR4). The virus-fusion protein (gp41) then gets uncovered and undergoes a conformational change. Glycoprotein gp41 inserts itself into the membrane of the host cell to initiate the fusion of the two bilayers.

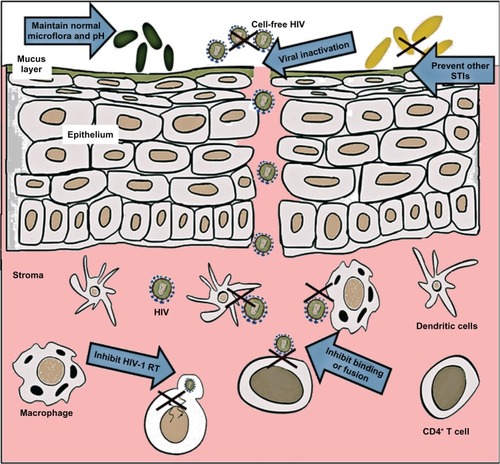

Viral RNA released into the cytoplasm undergoes reverse transcription with the help of the RT enzyme and is converted into DNA. This viral DNA enters the host cell nucleus, where it integrates in the host genetic material by the integrase enzyme. The integrated genome of HIV may lay dormant, until cellular transcription factors enhance transcription of the viral genome and trigger the production of viral proteins. HIV gene transcription from the integrated viral DNA (known as provirus) requires several host and viral proteins. The assembly and release (known as budding) of HIV from the host occurs in a series of organized steps that are driven by the viral gag protein.Citation25 Once the immature and noninfectious virus particles are released from the cell, further processing of gag polyproteins by HIV protease leads to the generation of mature infectious virus particles. Microbicides have been developed aiming to interfere at various stages of HIV-1 virus life cycle, as shown in .

Figure 1 Targeted modes of action of vaginally administered microbicides. To prevent HIV-1 infection, microbicides enabling vaginal milieu protection, such as lactobacilli or agents maintaining acidic pH of cervicovaginal fluid, have been developed. Microbicides based on surfactants are virucidal and inactivate cell-free virus. Microbicides can also be developed based on compounds that prevent binding, fusion or entry of HIV-1 to the host cells, such as CD4+ T cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. Among the more target-specific microbicides are those based on antiviral drugs, including inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT).

The establishment of infection at the portal of entry and timing of dissemination might also be affected by the number and types of cells that are initially infected. During male-to-female sexual transmission of HIV, following ejaculation, HIV is believed to remain infectious in semen for several hours, although the precise duration is not known.Citation26 During this time, diffusion is likely to be a principle mechanism of HIV transport from semen to vaginal epithelial surfaces. HIV-infected cells present in the semen can also cross the epithelial barrier, leading to transmission of HIV infection (transmigration). The available data suggest that susceptibility to HIV can be enhanced in the presence of an ulcerative STI, either through mucosal disruption or through increased number or activation of cells susceptible to HIV.Citation27 Nonulcerative infections have also been linked to increased susceptibility to HIV infection by triggering the proinflammatory responses that enhance viral replication or by proliferation of HIV-susceptible cells.Citation28

Based on their active properties, microbicides can be broadly classified into four categories: (1) inactivation of the virus; (2) inhibition of virus binding, fusion, or entry to the susceptible host cell; (3) inhibition of HIV replication in the host cells; and (4) maintenance or enhancement of the vaginal defense (). summarizes some of the microbicides that have undergone clinical trials in humans and the outcome of their efficacy to inhibit sexual transmission of HIV-1.

Table 1 Outcome of clinical trials in humans of some selected microbicides acting at different stages of the HIV life cycle

Inactivation of the virus

This class of inhibitors leads to disruption of the outer viral lipid membrane or acts by a tight and irreversible binding to the HIV envelope and hence inactivates the virus. Therefore, complete or even incomplete inactivation of cell-free or cell-associated HIV, or both, in semen by appropriate micro-bicides would prevent or markedly decrease the probability of virus transmission. Detergents or surfactants that destroy the integrity of the viral envelope by solubilizing membrane lipids or by denaturing viral proteins have been categorized under this class. Nonoxynol-9 (N-9), an anionic surfactant initially developed in the 1960s as a spermicide, was the first vaginal microbicide to be studied.Citation29 It has virucidal activity by disrupting the viral envelope. In a macaque vaginal challenge model, administration of N-9 led to reduction in transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus.Citation30 However, a Phase III multicentric randomized placebo-controlled trial (COL1492) in commercial sex workers showed that N-9 failed to prevent HIV transmission.Citation31 In fact, the transmission rate was marginally higher in the N-9 group compared to placebo control group. This may have been due to the development of lesions in the female reproductive tract as a consequence of its use.Citation32

C31G (Savvy; Cellegy Pharmaceutical, Quakertown, PA, USA), an equimolar mixture of two surface-active ampho-teric agents (cetyl betaine and myristamine oxide) buffered with citric acid, has shown in vitro safety and broad-spectrum activity against different bacteria and viruses, including C. trachomatis, HSV, and HIV.Citation33,Citation34 However, Phase III clinical studies in three countries revealed that C31G failed to demonstrate any protection against HIV-1 transmission.Citation35,Citation36 Further, its safety was a concern, as several adverse events associated with reproductive tract were reported.Citation35,Citation36 Sodium lauryl sulfate (Invisible Condom; Université Laval, Quebec, Canada), another surfactant has been shown to disrupt both nonenveloped and enveloped viruses.Citation37 A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled Phase II study in Cameroonian women revealed that the Invisible Condom gel formulation was well tolerated and acceptable.Citation38 Further phases of clinical development of Invisible Condom as a potential micro-bicide to prevent sexual transmission of HIV are awaited. Following the disappointment of microbicides based on nonspecific surfactant, attempts have been made to develop microbicides incorporating compounds that may interfere with HIV binding, fusion, or entry into the host cells and their subsequent replication.

Inhibition of virus binding, fusion, or entry to the susceptible host cell

Another broad class of microbicide agents are the fusion or entry inhibitors that block either attachment of HIV-1 to the host cells, the fusion of virus and host cell membranes, or the entry of HIV-1 into the host cells. Through their negative charge, a variety of anionic polymers inhibit the HIV adsorption and fusion process, and hence further infection. Pro 2000 (naphthalene sulfonate; Endo Health Solutions, Malvern, PA, USA) is a sulfonated polymer that interacts not only with viral gp120 but also with CD4 and CXCR4 receptors on the cell surface, and hence interferes with virus attachment or fusion with CD4+ T cells.Citation39 It possesses in vitro activity against both X4 and R5 strains of HIV, C. trachoma-tis, N. gonorrhoeae, and HSV.Citation40 However, the MDP-301 trials demonstrated conclusively that Pro 2000 was not effective in preventing HIV infection.Citation41 The Population Council (www.popcouncil.org) has developed Carraguard™, a sulfated poly-saccharide formulation, which is basically derived from red seaweed (Gigartina skottsbergii).Citation42 It blocks HIV-1 infection of cervical epithelial cells and trafficking of HIV-infected macrophages from the vagina to lymph nodes by binding to the HIV-1 envelope.Citation43 A large study in South Africa sponsored by the Population Council showed that the Carraguard gel was safe. Further Phase III trials revealed no difference in HIV incidence between users of Carraguard gel and placebo groups.Citation44 Another polyanion, Ushercell (cellulose sulfate; Polydex Pharmaceuticals, Toronto, ON, Canada), a contraceptive product possessing anti-HIV activity by binding to the V3 loop of gp120 of the HIV-1 envelope can inhibit the entry of both CXCR4 and CCR5-tropic virus.Citation45 However, different clinical trials indicated that it has no beneficial effect in curtailing the risk of HIV transmission and its use may increase the risk of HIV infection, possibly owing to toxicity of the active ingredient or the hyperosmolar gel vehicle (iso-osmolar placebo).Citation46,Citation47

Cellulose acetate phthalate (CAP) blocks gp120- and gp41-binding sites and has shown virucidal activity against HIV-1, HSV-1, and HSV-2.Citation48 CAP blocks infection of both cell-free and cell-associated HIV as well as blocks CXCR4 and CCR5-tropic virus types in tissue explants.Citation49 Its preclinical evaluation to date has shown neither any increase in the production of proinflammatory mediators during or after exposure, nor did it modify the epithelial resistance to leukocytes.Citation50 The micronized form of CAP (∼1 μm diameter) leads to disintegration and loss of infectivity of HIV-1, and its lack of systemic absorption increases its bioavailability to the topical surface.Citation51 However, due to heavy vaginal discharge in all the recipients of the CAP-based microbicide, the clinical trials were halted.Citation52

The CCR5 inhibitor PSC-RANTES (recombinant chemokine analogs), exhibits in vitro antiviral activity against most of the HIV clades and inhibits HIV-1 infection of Langerhans cells.Citation53 CCR5 inhibitors fully protect against simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) infection in the rhesus vaginal challenge model and are amenable to low-cost production, representing promising new additions to the microbicide pipeline.Citation54 TAK-779, a nonpeptide compound, binds specifically to the CCR5 coreceptor, and thereby selectively inhibits R5 HIV-1 entry and replication in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.Citation55 CMPD167, a cyclopentane-based compound, has been recently shown to protect macaques from vaginal challenge of CCR5-using SHIV162P3 and act synergistically or additively with other cell-entry inhibitors.Citation56 Maraviroc, a small-molecule drug that binds the CCR5 coreceptor and impedes HIV-1 entry into cells, has also been evaluated as a vaginal microbi-cide, and provided a dose-dependent protection against CCR5-using virus in rhesus macaques.Citation57 The bicyclam AMD3100 binds selectively to the CXCR4 coreceptor and inhibits entry of T-tropic HIV-1 and HIV-2.Citation58 TAK-779 and AMP3100, which block CCR5 and CXCR4 corecep-tors, respectively, may provide incomplete protection, as infection by migratory dendritic cells may still take place. However, inclusion of monoclonal antibody (mAb) b12 and CD4-immunoglobulin G2, both of which target gp120, reduced infection of T cells and migratory dendritic cells by more than 95% in activated cervical explant tissues.Citation59,Citation60 Hence, simultaneously blocking the pathways that lead to localized infection as well as viral dissemination represents better prevention from HIV-1 infection.

Carbohydrate-binding agents (CBAs) that bind to the HIV glycoprotein (gp120), facilitate the neutralization of a broad variety of HIV clades, including HIV-2 strains.Citation61 Examples of such CBAs are cyanobacterial cyanovirin-N (CV-N) purified from Nostoc ellipsosporum and several other plant lectins, including BanLec isolated from Musa acuminata (banana).Citation62,Citation63 CV-N demonstrated potent in vitro activity in the low nanomolar range against free as well as cell-associated HIV-1.Citation64 Additionally, it also inhibited infection of ectocervi-cal explants by HIV-1 as well as its dissemination by tissue-migratory cells.Citation64 Evaluation of CV-N gel (either 1% or 2%) as a topical rectal microbicide in male macaques (Macaca fascicularis) showed complete protection when challenged with SHIV89.6P.Citation65 Further, CV-N gel also showed protection in female macaques when challenged with SHIV89.6P, suggesting that it may be a suitable candidate for development of both rectal and vaginal microbicides.Citation66 Further, human vaginal commensal bacteria like Lactobacillus jensenii have been engineered to produce CV-N, and potent anti-HIV activity was exhibited by Lactobacillus-derived CV-N.Citation67 L. jensenii bacteria have also been engineered to secrete the anti-HIV-1 chemokine RANTES as well as C1C5 RANTES as a proof of concept for the use of L. jensenii-produced C1C5 RANTES to block HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells and macrophages, hence moving towards the development of a live anti-HIV-1 microbicide.Citation68 Since most cells of human origin have glycoproteins expressed on their surface, highly selective CBA should be designed, and side effects of CBA should be evaluated carefully.Citation69

Interaction with either CCR5 or CXCR4 coreceptors triggers a rearrangement of the transmembrane subunit of the envelope glycoprotein gp41, which leads to fusion between the virus and cell membrane, and hence inhibiting gp41-mediated virus–cell fusion is also a promising approach. A proof of concept for this approach has been established with the use of enfuvirtide (T-20 peptide), which blocks virus entry at the stage of HIV-envelope fusion with the cell membrane by targeting gp41.Citation70 It was the first antiretroviral agent to act by inhibiting the fusion of HIV-1 with CD4+ T cells to be approved by the US FDA, in 2003. It possesses potent antiviral activity, but has two critical drawbacks: high cost of production and short in vivo half-life.Citation71 C52L, a peptide that also inhibits gp41-mediated virus–cell fusion, is another potent and broad inhibitor of viral infection that remains fully active against T-20-resistant HIV-1.Citation72

Dendrimers are highly branched macromolecules syn-thesized from a polyfunctional core, with interior branches and terminal surface groups adapted to specific targets. The first dendrimer formulated and tested as a microbicide gel clinically was SPL7013 (VivaGel; Starpharma, Melbourne, Australia). SPL7013, a lysine-based dendrimer with naphthalene disulfonic acid surface groups, was optimized and found potent against HIV and HSV.Citation73 In a Phase I clinical trial, it was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy women, with no evidence of systemic toxicity or absorption.Citation74

Neutralizing mAbs to gp120 (surface glycoprotein of HIV envelope) and gp41 (the fusion transmembrane gly-coprotein) have broad neutralizing activity against primary HIV-1 isolates. Moreover, researchers have recently shown that a combination of different mAbs (b12, 2G12, 2F5, and 4E10) showed neutralization synergy.Citation75

Inhibition of HIV replication in the host cells

Once in the intracellular environment, HIV infection can only be stopped through inhibition of the virus-encoded RT or integrase. TDF is one of the important compounds being used in HAART drug regimens. TFV 1% gel either alone or in combination with emtricitabine (5% gel) showed its efficacy to prevent sexual transmission of SHIV in pigtailed macaques.Citation76,Citation77 After careful pharmacokinetic and safety studies, TFV 1% gel was evaluated in Phase IIb studies in women for its efficacy to prevent sexual transmission of HIV.Citation78 The Centre for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA) 004 study for the first time indicated that PrEP with TFV was successful in prevention against HIV infection.Citation79 The dosing regimen comprised using gel within 12 hours before coitus and a second dose as soon as possible after coitus but not exceeding 24 hours of the first dose. The success of this study has buoyed the microbicide field, providing the first proof of principle that vaginal microbicide gels can successfully function in a clinical trial setting to reduce the rate of HIV transmission. The TFV gel users were 39% less likely to become infected with HIV than other women, who received a placebo gel. TFV gel also reduced the rate of new genital herpes infections.Citation80

The Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) conducted another Phase IIb safety and efficacy trial – the Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic (VOICE) study – that tested two different HIV-prevention methods, oral PrEP (Viread and Truvada®) and a vaginal microbicide gel (1% TFV), with both pills and gel used daily regardless of sexual activity. Both the oral Viread and Truvada arms failed to show any effective decrease in HIV transmission. Further, HIV incidence was almost identical in women using TFV gel and the ones using placebo gel. As a result, both the TFV-gel and placebo-gel arms have now been stopped. The reasons for the differential efficacy of TFV 1% gel to prevent HIV transmission in the CAPRISA 004 and VOICE studies are not clear. One of the possible reasons may be the adherence towards usage of microbicides as advised.Citation81 Prior to the announcement of VOICE results, another Phase III efficacy trial of TFV 1% gel was initiated in South Africa – Follow-on African Consortium for Tenofovir Studies (FACTS) 001 – using the same dosing regimen as in the CAPRISA 004 trial. The study is likely to be completed in 2014 ().

Table 2 Microbicides in the pipeline undergoing Phase III clinical trial for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1

HIV-1-specific NNRTIs compared to NRTIs have the advantage of a very high therapeutic index and acting directly (without metabolization) against the virus replication. Two NNRTI-based microbicides, TMC120 (dapivirine) and UC781, are the most advanced in clinical trials as potential topical microbicides, and usually require at least two mutations before viral resistance occurs.Citation82,Citation83 These small molecules with low solubility in water or physiological fluids have the potential to form a long-lasting “depot” at sites susceptible to cervicovaginal HIV infection. This could allow application of the microbicide well before sexual intercourse.Citation84 However, the extremely poor water solubility of UC781 leads to a great challenge for its formulation development. A beta-cyclodextran-based drug-delivery system is being developed to enhance the aqueous solubility of UC781.Citation85 Recently, an ongoing, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, Phase IIb clinical trial concluded that lersivirine (UK-453,061), a next generation NNRTI, is safe and displayed comparable efficacy to efavirenz in the treatment of naïve HIV-1-infected patients.Citation86

Among the integrase inhibitors, raltegravir was the first to be approved by the FDA, in 2007, to overcome the problem of multidrug resistance in AIDS patients. In August 2012, elvitegravir was also approved by the FDA as the second integrase inhibitor.Citation87 Subsequently, Stribild®, a single daily tablet comprising elvitegravir, cobicistat (pharmaco-enhancing agent), emtricitabine (NRTI), and TDF (NRTI), was formulated by Gilead Sciences for treatment of naïve HIV-infected human subjects.Citation88 A Phase III trial revealed that Stribild is effective in decreasing the viral load (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL blood) in naïve HIV-infected subjects.Citation89

Maintenance or enhancement of the vaginal defense

The other broad class of microbicides under development is vaginal milieu protectors that work to maintain, restore, or enhance the natural protective mechanisms within the vagina. The pH in cervicovaginal fluid is acidic (3.5–4.5), and is important for innate immunity against STI-causing pathogens, including HIV. The alkaline nature of semen (pH 7.1–8.0), after coming in contact with the vagina, leads to an increase in the pH, thereby diminishing the natural defense mechanisms. Hence, the compounds that preserve the acidic pH in the vaginal environment, thereby increasing the instability of the virus particles, are the main compounds in this category. To re-acidify the vaginal environment, Lactobacillus suppositories or “probiotics” that maintain the acidic pH, primarily due to the production of lactic acid and H2O2, can be used. A pH between 4.0 and 5.8 has been shown to inactivate HIV. Colonization of exogenous lactobacilli has been shown to correlate with decreased HIV proliferation.Citation20,Citation90

A polyacrylic acid, Carbopol® 974P (BufferGel®; ReProtect, Baltimore, MD, USA), which buffers twice its volume of semen to a pH of 5.0 or less, has been shown to be spermicidal and virucidal to HIV, HSV, C. trachomatis, and human papillomavirus. However, during clinical trials, BufferGel was found to have no effect on preventing HIV infection.Citation91 Acidform (Amphora; Evofem, San Diego, CA, USA) is currently approved as a sexual lubricant gel. Its acid-buffering and bioadhesive properties make it a suitable candidate for microbicide development. A Phase I study revealed that Acidform was well tolerated when used alone, but produced vaginal irritation when combined with N-9.Citation92 Naturally occurring acidic compounds, such as lime juice, have also been found to be effective against HIV infection, but clinical trials of formulations based on lime juice have shown toxicity.Citation93

Use of microbicides: acceptability and adherence

Acceptability studies in a range of countries, such as Brazil, India, South Africa, Thailand, the US, and Zimbabwe, have revealed that women by and large show a positive attitude towards the use of microbicides for prevention of sexually transmitted HIV infection. Further, men are also supportive of the idea of use of microbicide.Citation94 Vaginal microbicides have been found to be acceptable to adolescent girls, women, and heterosexual men, and rectal microbicides were acceptable to men who have sex with men.Citation95 The biggest advantage of microbicides is their ease of use, hence providing privacy. Consumer product-preference studies conducted on 526 sexually active women in Burkina Faso, Tanzania, and Zambia revealed that 80% of women liked using all three forms of products, namely vaginal tablets, film, and soft-gel capsules.Citation96 However, compared to vaginal tablets, film and soft-gel capsules were preferred, and was not associated with age of the participants, socioeconomic status, or marital status.Citation96 A Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Pune, India of a vaginal polyherbal tablet microbicide used in a coitally dependent manner revealed that 70.5% of participants showed 100% adherence.Citation97 Undesirable sexual experience and odor of the product were major barriers to its adherence. In another study done in couples in Mexico, it was suggested that use of microbicides by the female partner could imply mistrust/infidelity in the mind of the male partner within their intimate relationship.Citation98

Consideration of microbicides for prevention of HIV transmission should take into account intimate relationship dynamics, which may be a potential barrier to their acceptability and adherence; therefore, the involvement of male partners and promoting risk-communication skills are important for better compliance in the use of microbicides.Citation98 One of the reasons for low adherence in women of PrEP vaginal microbicides may be the perception that they do not see themselves at risk of HIV infection. The use of topical PrEP vaginal microbicide in a coitally dependent manner may be easier for women to adhere to compared to coitally independent once-daily dosing. To improve acceptability and adherence of topical PrEP microbicide, either long-acting microbicides or MPTs have been proposed.

Long-acting microbicide

Intravaginal rings (IVRs) incorporating antiretroviral drugs have been designed with the premise that the drug will be slowly released over a long period of time, thereby increasing compliance/adherence.Citation99,Citation100 An IVR for contraception, namely NuvaRing (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), has been well accepted by women.Citation101 The majority of the participants were willing to use IVRs for HIV-1 prevention in a study from Kenya involving men and at-risk women. However, the risk of its covert use by women and discovery by the male partner may have an impact on its use.Citation102 IVRs based on hydrophilic polyurethanes have been developed for long-term release (over 90 days) of polar drugs such as TFV or TDF.Citation103,Citation104 An IVR based on DPV, a potent NNRTI, has also been designed.Citation105 An IVR incorporating DPV is currently undergoing two different Phase III clinical trials: ASPIRE (A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use), conducted by the MTN in several sub-Saharan countries, and the Ring Study (IPM 027), the outcome of which will be known in 2015. Additionally, IVR incorporating DPV and the CCR5 inhibitor maraviroc has also been formulated, which is undergoing Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic studies (MTN 013).Citation106

Multipurpose technologies

To enhance the acceptability and adherence of vaginal/rectal microbicides, MPTs are being developed that aim simultaneously to inhibit HIV-1 infections and other STIs. In this direction, the Population Council is developing MPTs that may be effective against HIV-1, human papilloma virus, and HSV-2 using a combination of MIV-150, carrageenan, and zinc acetate.Citation107,Citation108 Various combinations of MIV-150, car-rageenan, and zinc acetate have shown efficacy in preventing both vaginal and rectal transmission of RT-SHIV and HSV-2.Citation109,Citation110 Further, MPTs that are capable of preventing sexual transmission of HIV-1 and also have contraceptive efficacy are being developed, and will have greater acceptability among women.Citation111,Citation112

Challenges in microbicide development

Several microbicide clinical trials based on the successful in vitro anti-HIV efficacy of the microbicide candidates, however, have failed to demonstrate in vivo efficacy, presenting (except the CAPRISA 004 trial) the discrepancies between the in vitro and in vivo data. A reevaluation of the current microbicide-development paradigm and a renewed approach for preclinical testing systems that can predict negative outcomes of microbicide clinical trials is necessary. There are at least two important issues: (1) the microbicide should not have any effect on vaginal mucosa, and (2) the microbicide should not generate any proinflammatory response. To determine preclinical efficacy as well as safety of the candidate topical microbicides, human cervical and colorectal explant cultures have been developed.Citation113,Citation114 Further, a three-dimensional in vitro human vaginal epithelial cell model has been developed that mimics human stratified squamous epithelium with microvilli, tight junctions, micro-folds, and mucus.Citation115 Using this model, N-9 treatment led to an increase in tumor necrosis factor-associated apoptosis as well as biomarkers of cervicovaginal inflammation.Citation115 There is a need to develop additional cell-based and explant-based models for discovering new biomarkers of cervicovaginal inflammation for assessment of microbicide safety before clinical evaluation can be initiated.Citation116

For testing the safety and efficacy of the microbicide candidates, the absence of a validated animal model is a major obstacle. The animal models used currently (the mouse HSV-2 model, the rabbit vaginal irritation index, and the macaque SIV model) have substantial differences from humans. However, recent advances include the development of humanized murine models, which allow better vaginal and rectal HIV efficacy-challenge studies.Citation117 To evaluate proin-flammatory response and disruption of mucosal integrity by a candidate microbicide that may facilitate transepithelial viral penetration as well as replication, a Th17-based mouse model has been developed for preclinical assessment.Citation118 The sheep cervicovaginal tract, which comprises stratified squamous epithelium similar to humans supplemented with optical coherence tomography, may also constitute one of the large animal models before testing the microbicides in either nonhuman primates or humans.Citation119 A lack of markers for the biological activity of the microbicides as well as correlates of protection also poses a big hindrance. Hence, the development of surrogate markers of the efficacy of microbicides will help in moving forward in this area.

A candidate microbicide’s efficacy is underestimated if the placebo itself provides a certain degree of protection against HIV-1 infection. On the other hand, a placebo leading to epithelial toxicity that increases susceptibility towards HIV-1 infection may result in false efficacy to prevent HIV-1 infection of the microbicide undergoing clinical trial. Hence, the development of an inert universal placebo that is stable, safe, and acceptable is also an important issue while conducting clinical trials of microbicides. A hydroxy-ethyl cellulose placebo formulation has been developed that appeared to be safe and acceptable when used twice daily for 14 days.Citation120,Citation121

The VOICE clinical trials of PrEP of vaginal 1% TFV gel used once daily regardless of sexual activity revealed that adherence to the use of microbicide can also be an important issue. It is imperative to develop new quantitative measures to monitor adherence. Used applicators can be tested by staining methods or by ultraviolet light to know if they have come in contact with the vaginal surface.Citation122 The participation of multiple countries in microbicide clinical trials has its own unique challenges. Both ethical and regulatory approvals not only in the country of the trial sponsor but also in each country where the trial will be held need to be granted. Recruiting the required number of women and ensuring their stay in the trial is also challenging; maintaining the tracing mechanisms and databases to keep track of the participants is also one of the major challenges. A difficult but important issue in HIV trials is the care of people who seroconvert during the study. The formation of a coordination body that would help facilitate harmonizing across a number of areas, including protocol design, monitoring, and decision-making for next-generation candidate microbicides, has been convened by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Alliance for Microbicide Development. summarizes the microbicides that are undergoing thorough Phase III clinical trials including stribild and VivaGel (SPL-7013).Citation123,Citation124 The outcome of these trials is eagerly awaited, and will facilitate the next generation of microbicides.

New information and essential lessons have emerged in this field as a result of each of these challenges. These have also resulted in a momentous increase in microbicide-development efforts focusing on compounds with highly potent and HIV-specific mechanisms of action, combination products, novel formulations, and carefully designed pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluations, all of which are reasons for renewed confidence that a safe and effective microbicide is achievable. The development of MPTs that can simultaneously address the issue of sexual transmission of HIV-1 and contraception may be acceptable with increased adherence.

Conclusion

To prevent sexual transmission of HIV-1, topical micro-bicides have been proposed. In spite of good anti-HIV-1 activity in various in vitro assays and challenge experiments in macaques, clinical trials of microbicides based on surfactants and polyanions failed to inhibit sexual transmission of HIV-1. Unfortunately, microbicides based on N-9 enhanced the susceptibility of sexual transmission of HIV-1. Microbicides based on antiretroviral drugs such as TFV (1% gel) showed moderate efficacy in the CAPRISA 004 clinical trial, but failed to inhibit sexual transmission of HIV-1 in the VOICE Phase IIb clinical trial. Though the reasons for these contradictory observations are not clear, pharmacodynamic studies suggest that poor adherence may be responsible for the lack of efficacy in the VOICE study. The ongoing efficacy trials of microbicides based on antiretroviral drugs, namely TFV and dapivirine, will help in establishing their utility or otherwise in preventing sexual transmission of HIV-1. The next generation of microbicides will comprise MPTs, which are effective not only against HIV-1 but also against other STIs. Development of long-acting (up to 90 days) delivery systems for the microbicides will act as an impetus for the development of this field.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge financial support from the Department of Biotechnology and the Indian Council of Medical Research, Government of India. The authors thank Ms Shruti Upadhyay for help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDSWorld AIDS Day Report – 2011GenevaUNAIDS2011 Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/jc2216_worldaidsday_report_2011_en.pdfAccessed August 26, 2013

- RossDABehavioural interventions to reduce HIV risk: what works?AIDS201024Suppl 4S4S1421042051

- De ClercqEThe history of antiretrovirals: key discoveries over the past 25 yearsRev Med Virol200919528729919714702

- EsteJACihlarTCurrent status and challenges of antiretroviral research and therapyAntiviral Res2010851253320018390

- DybulMFauciASBartlettJGKaplanJEPauAKGuidelines for using antiretroviral agents among HIV-infected adults and adolescentsAnn Intern Med20021375 Pt 238143312617573

- GrantRMLamaJRAndersonPLPreexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with menN Engl J Med2010363272587259921091279

- HofmanPNelsonAMThe pathology induced by highly active anti-retroviral therapy against human immunodeficiency virus: an updateCurr Med Chem200613263121313217168701

- AgwuALindseyJCFergusonKAnalyses of HIV-1 drug-resistance profiles among infected adolescents experiencing delayed antiretroviral treatment switch after initial nonsuppressive highly active antiretroviral therapyAIDS Patient Care STDS200822754555218479228

- KeeferMCGrahamBSBelsheRBStudies of high doses of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 recombinant glycoprotein 160 candidate vaccine in HIV type 1 seronegative humans. The AIDS Vaccine Clinical Trials NetworkAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses19941012171317237888231

- McElrathMJCoreyLGreenbergPDHuman immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection despite prior immunization with a recombinant envelope vaccine regimenProc Natl Acad Sci U S A1996939397239778633000

- GilbertPBPetersonMLFollmannDCorrelation between immunologic responses to a recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine and incidence of HIV-1 infection in a phase 3 HIV-1 preventive vaccine trialJ Infect Dis2005191566667715688279

- RussellNDGrahamBSKeeferMCPhase 2 study of an HIV-1 canarypox vaccine (vCP 1452) alone and in combination with rgp 120: negative results fail to trigger a phase 3 correlates trialJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200744220321217106277

- BuchbinderSPMehrotraDVDuerrAEfficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trialLancet200837296531881189319012954

- de SouzaMSRatto-KimSChuenaromWThe Thai phase III trial (RV144) vaccine regimen induces T-cell responses that preferentially target epitopes within the V2 region of HIV-1 envelopeJ Immunol2012188105166517622529301

- WalkerLMPhogatSKChan-HuiPYBroad and potent neutral-izing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine targetScience2009326595028528919729618

- KwongPDMascolaJRNabelGJRational design of vaccines to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med201111a00727822229123

- WalkerLMHuberMDooresKJBroad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodiesNature2011477736546647021849977

- DoncelGMauckCVaginal microbicides: a novel approach to preventing sexual transmission of HIVCurr HIV/AIDS Rep200411253216091220

- ZewdieDHolschneiderSExpanding on preventing options: the role of the international community in providing an enabling environment of microbicidesAIDS200115Suppl 1S5S611293386

- KlebanoffSJCoombsRWVirucidal effect of Lactobacillus aci-dophilus on human immunodeficiency virus type 1: possible role in heterosexual transmissionJ Exp Med199117412892921647436

- KlatzmannDChampagneEChamaretST-lymphocyte T4 molecule behaves as the receptor for human retrovirus LAVNature198431259967677686083454

- AlkhatibGCombadiereCBorderCCCC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, MIP-1beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1Science19962725270195519588658171

- FengYBroderCCKennedyPEBergerEAHIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptorScience199627252638728778629022

- BergerEAMurphyPMFarberJMChemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and diseaseAnnu Rev Immunol19991765770010358771

- FreedEOHIV-1 gag protein: diverse functions in the virus life cycleVirology199825111159813197

- HaaseATPerils at mucosal front lines for HIV and SIV and their hostsNat Rev Immunol200551078379216200081

- GuthrieBLKiarieJNMorrisonSSexually transmitted infections among HIV-1-discordant couplesPLoS One2009412e827620011596

- LagaMManokaAKivuvuMNon-ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV-1 transmission in women: results from a cohort studyAIDS199371951028442924

- BourinbaiarASFruhstorferECThe efficacy of nonoxynol-9 from an in vitro point of viewAIDS19961055585598724057

- MillerCJAlexanderNJGettieAHendrickxAGMarxPAThe effect of contraceptives containing nonoxynol-9 on the genital transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus in rhesus macaquesFertil Steril1992575112611281315297

- Van DammeLRamjeeGAlaryMEffectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trialLancet2002360933897197712383665

- StaffordMKWardHFlanaganASafety study of nonoxynol-9 as a vaginal microbicide: evidence of adverse effectsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol19981743273319525433

- WyrickPBKnightSTGerbigDGJrThe microbicidal agent C31G inhibits Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity in vitroAntimicrob Agents Chemother1997416133513449174195

- KrebsFCMillerSRCataloneBJSodium dodecyl sulfate and C31G as microbicidal alternatives to nonoxynol 9: comparative sensitivity of primary human vaginal keratinocytesAntimicrob Agents Chemother20004471954196010858360

- PetersonLNandaKOpokuBKSAVVY (C31G) gel for prevention of HIV infection in women: a phase 3, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in GhanaPLoS One2007212e131218091987

- FeldblumPJAdeigaABakareRSAVVY vaginal gel (C31G) for prevention of HIV infection: a randomized controlled trial in NigeriaPLoS One200831e147418213382

- PiretJDesormeauxABergeronMGSodium lauryl sulfate, a microbi-cide effective against enveloped and nonenveloped virusesCurr Drug Targets200231173011899262

- Mbopi-KeouFXTrottierSOmarRFA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II extended safety study of two invisible condom formulations in Cameroonian womenContraception2010811798520004278

- HuskensDVermeireKProfyATScholsDThe candidate sulfonated microbicide, PRO 2000, has potential multiple mechanisms of action against HIV-1Antiviral Res2009841384719664662

- KellerMJZerhouni-LayachiBCheshenkoNPRO2000 gel inhibits HIV and herpes simplex virus infection following vaginal application: a double-blind placebo-controlled trialJ Infect Dis20061931273516323128

- AbdoolKarimSSResults of effectiveness trials of PRO2000 gel: lessons for future microbicide trialsFuture Microbiol20105452752920353292

- SchaefferDJKrylovVSAnti-HIV activity of extracts and compounds from algae and cyanobacteriaEcotoxicol Environ Saf200045320822710702339

- PerottiMEPirovanoAPhillipsDMCarrageenan formulation prevents macrophage trafficking from vagina: implications for microbicide developmentBiol Reprod200369393393912773428

- Skoler-KarpoffSRamjeeGAhmedKEfficacy of Carraguard for prevention of HIV infection in women in South Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet200837296541977198719059048

- Scordi-BelloIAMosoianAHeCCandidate sulfonated and sulfated topical microbicides: comparison of anti-human immunodeficiency virus activities and mechanisms of actionAntimicrob Agents Chemother20054993607361516127029

- FuchsEJLeeLATorbensonMSHyperosmolar sexual lubricant causes epithelial damage in the distal colon: potential implication for HIV transmissionJ Infect Dis2007195570371017262713

- HalpernVOgunsolaFObungeOEffectiveness of cellulose sulfate vaginal gel for the prevention of HIV infection: results of a phase III trial in NigeriaPLoS One2008311e378419023429

- NeurathARStrickNLiYYWater dispersible microbicidal cellulose acetate phthalate filmBMC Infect Dis200332714617380

- LuHZhaoQWallaceGCellulose acetate 1,2-benzenedicarboxylate inhibits infection by cell-free and cell-associated primary HIV-1 isolatesAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses200622541141816706617

- FichorovaRNZhouFRatnamVAnti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 microbicide cellulose acetate 1,2-benzenedicarboxylate in a human in vitro model of vaginal inflammationAntimicrob Agents Chemother200549132333515616312

- NeurathARStrickNLiYYLinKJiangSDesign of a “microbi-cide” for prevention of sexually transmitted diseases using “inactive” pharmaceutical excipientsBiologicals1999271112110441398

- LaceyCJWoodhallSQiZUnacceptable side effects associated with a hyperosmolar vaginal microbicide in a phase 1 trialInt J STD AIDS2010211071471721139151

- KawamuraTGuldenFOSugayaMR5 HIV productively infects Langerhans cells, and infection levels are regulated by compound CCR5 polymorphismsProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2003100148401840612815099

- VeazeyRSLingBGreenLCTopically applied recombinant chemokine analogues fully protect macaques from vaginal simian-human immunodeficiency virus challengeJ Infect Dis2009199101525152719331577

- BabaMNishimuraOKanzakiNA small-molecule, nonpeptide CCR5 antagonist with highly potent and selective anti-HIV-1 activityProc Natl Acad Sci U S A199996105698570310318947

- VeazeyRSKlassePJSchaderSMProtection of macaques from vaginal SHIV challenge by vaginally delivered inhibitors of virus-cell fusionNature200543870649910216258536

- VeazeyRSKetasTJDufourJProtection of rhesus macaques from vaginal infection by vaginally delivered maraviroc, an inhibitor of HIV-1 entry via the CCR5 co-receptorJ Infect Dis2010202573974420629537

- HatseSPrincenKGerlachLOMutation of Asp(171) and Asp(262) of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 impairs its coreceptor function for human immunodeficiency virus-1 entry and abrogates the antagonistic activity of AMD3100Mol Pharmacol200160116417311408611

- AllawayGPDavis-BrunoKLBeaudryGAExpression and characterization of CD4-IgG2, a novel heterotetramer that neutralizes primary HIV type 1 isolatesAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses19951155335397576908

- BurtonDRPyatiJKoduriREfficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibodyScience19942665187102410277973652

- BalzariniJVan LaethemKHatseSCarbohydrate-binding agents cause deletions of highly conserved glycosylation sites in HIV GP120: a new therapeutic concept to hit the Achilles heel of HIVJ Biol Chem200528049410054101416183648

- BoydMRGustafsonKRMcMohanJBDiscovery of cyanovirin-N, a novel human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein that binds viral surface envelope glycoprotein gp120: potential applications to microbicide developmentAntimicrob Agents Chemother1997417152115309210678

- SwansonMDWinterHCGoldsteinIJMarkovitzDMA lectin isolated from bananas is a potent inhibitor of HIV replicationJ Biol Chem2010285128646865520080975

- BuffaVStiehDMamhoodNHuQFletcherPShattockRJCyanovirin-N potently inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in cellular and cervical explant modelsJ Gen Virol200990Pt 123424319088294

- TsaiCCEmauPJiangYCyanovirin-N gel as a topical micro-bicide prevents rectal transmission of SHIV89.6P in macaquesAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses200319753554112921090

- TsaiCCEmauPJiangYCyanovirin-N inhibits AIDS virus infections in vaginal transmission modelsAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses2004201111815000694

- LiuXLagenaurLALeePPXuQEngineering of a human vaginal Lactobacillus strain for surface expression of two-domain CD4 moleculesAppl Environ Microbiol200874154626463518539799

- VangelistaLSecchiMLiuXEngineering of Lactobacillus jensenii to secrete RANTES and a CCR5 antagonist analogue as live HIV-1 blockersAntimicrob Agents Chemother20105472994300120479208

- BalzariniJTargeting the glycans of gp120: a novel approach aimed at the Achilles heel of HIVLancet Infect Dis200551172673116253890

- WildCTShugarsDCGreenwellTKMcDanalCBMatthewsTJPeptides corresponding to a predictive alpha-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infectionProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19949121977097747937889

- KilbyJMEronJJNovel therapies based on mechanisms of HIV-1 cell entryN Engl J Med2003348222228223812773651

- KetasTJSchaderSMZuritaJEntry inhibitor-based microbicides are active in vitro against HIV-1 isolates from multiple genetic subtypesVirology2007364243144017428517

- TyssenDHendersonSAJohnsonAStructure activity relationship of dendrimer microbicides with dual action antiviral activityPLoS One201058e1230920808791

- O’LoughlinJMillwoodIYMcDonaldHMPriceCFKaldorJMPaullJRSafety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of SPL7013 gel (VivaGel): a dose ranging, phase I studySex Transm Dis201037210010419823111

- ZwickMBWangMPoignardPNeutralization synergy of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates by cocktails of broadly neutralizing antibodiesJ Virol20017524121981220811711611

- ParikhUMDobardCSharmaSComplete protection from repeated vaginal simian-human immunodeficiency virus exposures in macaques by a topical gel containing tenofovir alone or with emtricitabineJ Virol20098320103581036519656878

- DobardCSharmaSMartinADouble protection from vaginal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection in macaques by tenofovir gel and its relationship to drug levels in tissuesJ Virol201286271872522072766

- MayerKHMaslankowskiLAGaiFSafety and tolerability of tenofovir vaginal gel in abstinent and sexually active HIV-infected and uninfected womenAIDS200620454355116470118

- Abdool KarimQAbdool KarimSSFrohlichJAEffectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in womenScience201032959961168117420643915

- TanDPotential role of tenofovir vaginal gel for reduction of risk of herpes simplex virus in femalesInt J Womens Health2012434135022927765

- Van der StratenAVan DammeLHabererJEBangsbergDRUnraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV preventionAIDS2012267F13F1922333749

- Van HerrewegeYMichielsJVan RoeyJIn vitro evaluation of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors UC-781 and TMC120-R147681 as human immunodeficiency virus microbicidesAntimicrob Agents Chemother200448133733914693562

- FletcherPHarmanSAzijnHInhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by the candidate microbicide dapivirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitorAntimicrob Agents Chemother200953248749519029331

- Di FabioSVan RoeyJGianniniGInhibition of vaginal transmission of HIV-1 in hu-SCID mice by the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor TMC120 in a gel formulationAIDS200317111597160412853741

- YangHParniakMAIsaacsCEHillierSLRohanLCCharacterization of cyclodextrin inclusion complexes of the anti-HIV non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor UC781AAPS J200810460661319089644

- VernazzaPWangCPozniakAEfficacy and safety of lersivirine (UK-453,061) versus efavirenz in antiretroviral treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: week 48 primary analysis results from an ongoing, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase IIb trialJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201362217117923328090

- WainbergMAMesplèdeTQuashiePKThe development of novel HIV integrase inhibitors and the problem of drug resistanceCurr Opin Virol20122565666222989757

- MarchandCThe elvitegravir Quad pill: the first once-daily dual-target anti-HIV tabletExpert Opin Investig Drugs2012217901904

- ZolopaASaxPEDeJesusEA randomized double-blind comparison of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 96 resultsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20136319610023392460

- MartinHLRichardsonBANyangePMVaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisitionJ Infect Dis199918061863186810558942

- Abdool KarimSSRichardsonBARamjeeGSafety and effectiveness of BufferGel and 0.5% PRO2000 gel for the prevention of HIV infection in womenAIDS201125795796621330907

- AmaralEFaúndesAZaneveldLWallerDGargSStudy of the vaginal tolerance to Acidform, an acid-buffering, bioadhesive gelContraception199960636136610715372

- HemmerlingAPottsMWalshJYoung-HoltBWhaleyKStefanskiDALime juice as a candidate microbicide? An open-label safety trial of 10% and 20% lime juice used vaginallyJ Womens Health (Larchmt)20071671041105117903081

- RamjeeGMorarNSBraunsteinSFriedlandBJonesHvan de WijgertJAcceptability of Carraguard, a candidate microbicide and methyl cellulose placebo vaginal gels among HIV-positive women and men in Durban, South AfricaAIDS Res Ther200742017900337

- ColyAGarbachPMMicrobicide acceptability research: recent findings and evolution across phases of product developmentCurr Opin HIV AIDS20083558158619373025

- NelAMMitchnickLBRishaPMuungoLTNorichPMAcceptability of vaginal film, soft-gel capsule and tablet as potential microbicide delivery methods among African womenJ Womens Health (Larchmt)20112081207121421774672

- JoglekarNSJoshiSNDeshpandeSSParkheANKattiURMehendaleSMAcceptability and adherence: findings from a phase II study of a candidate vaginal microbicide, ‘Praneempolyherbal tablet’, in Pune, IndiaTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg2010104641241520096909

- RobertsonAMSyvertsenJLMartinezGAcceptability of vaginal microbicides among female sex workers and their intimate male partners in two Mexico-US border cities: a mixed methods analysisGlob Public Health20138561963323398385

- KiserPFJohnsonTJClarkJTState of the art in intravaginal ring technology for topical prophylaxis of HIV infectionAIDS Rev2012141627722297505

- MalcolmKFetherstonSMMcCoyCFBoydPMajorIVaginal rings for delivery of HIV microbicidesInt J Womens Health2012459560523204872

- NovakAde la LogeCAbetzLvan der MeulenEAThe combined contraceptive vaginal ring, NuvaRing: an international study of user acceptabilityContraception200367318719412618252

- ClarkJTJohnsonTJClarkMRQuantitative evaluation of a hydrophilic matrix intravaginal ring for the sustained delivery of tenofovirJ Control Release2012163224024822981701

- JohnsonTJClarkMRAlbrightTHA 90-day tenofovir reservoir intravaginal ring for mucosal HIV prophylaxisAntmicrob Agents Chemother2012561262726283

- MesquitaPMRastogiRSegarraTJIntravaginal ring delivery of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of HIV and herpes simplex virus infectionJ Antimicrob Chemother20126771730173822467632

- SmithDJWakasiakaSHoangTDBwayoJJDel RioCPriddyFHAn evaluation of intravaginal rings as a potential HIV prevention device in urban Kenya: Behaviors and attitudes that might influence uptake within a high-risk populationJ Womens Health (Larchmt)20081761025103418681822

- FetherstonSMBoydPMcCoyCFA silicon elastomer vaginal ring for HIV prevention containing two microbicides with different mechanisms of actionEur J Pharm Sci201248340641523266465

- ArensMTravisSZinc salts inactivate clinical isolates of herpes simplex virus in vitroJ Clin Microbiol20003851758176210790094

- BuckCBThompsonCDRobertsJNMüllerMLowyDRSchillerJTCarrageenan is a potent inhibitor of papillomavirus infectionPLoS Pathog200627e6916839203

- SingerRDerbyNRodriguezAThe nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor MIV-150 in carrageenan gel prevents rectal transmission of simian/human immunodeficiency virus infection in macaquesJ Virol201185115504551221411526

- Fernández-RomeroJAAbrahamCJRodriguezAZinc acetate/carrageenan gels exhibit potent activity in vivo against high-dose herpes simplex virus 2 vaginal and rectal challengeAntimicrob Agents Chemother201256135836822064530

- FriendDRDoncelGFCombining prevention of HIV-1, other sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies: development of dual-protection technologiesAntiviral Res201088Suppl 1S47S5421109068

- BallCKrogstadEChaowanachanTWoodrowKADrug-eluting fibers for HIV-1 inhibition and contraceptionPLoS One2012711e4979223209601

- FletcherPSElliottJGrivelJCEx vivo culture of human colorectal tissue for the evaluation of candidate microbicidesAIDS20062091237124516816551

- CumminsJEJrGuarnerJFlowersLPreclinical testing of candidate topical microbicides for anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity and tissue toxicity in a human cervical explant cultureAntimicrob Agents Chemother20075151770177917353237

- HzelmBEBertaANNickersonCAArntzenCJHerbst-KralovetzMMDevelopment and characterization of a three-dimensional organotypic human vaginal epithelial cell modelBiol Reprod201082361762720007410

- CumminsJEJrDoncelGFBiomarkers of cervicovaginal inflammation for the assessment of microbicide safetySex Transm Dis200936Suppl 3S84S9119218890

- DentonPWEstesJDSunZAntiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis prevents vaginal transmission of HIV-1 in humanized BLT micePLoS Med200851e1618198941

- LiLZYangYYuanSHEstablishing a Th17 based mouse model for preclinical assessment of the toxicity of candidate microbicidesChin Med J (Engl)2010123233381338822166518

- VincentKLBoumeNBellBAHigh resolution imaging of epithelial injury in the sheep cervicovaginal tract: a promising model for testing safety of candidate microbicidesSex Transm Dis200936531231819295469

- TienDSchnaareRLKangFIn vitro and in vivo characterization of a potential universal placebo designed for use in vaginal microbicide clinical trialsAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses2005211084585316225411

- SchwartzJLBallaghSAKwokCFourteen-day safety and acceptability study of the universal placebo gelContraception200775213614117241844

- MoenchTRO’HanlonDConeEEvaluation of microbicide gel adherence monitoring methodsSex Transm Dis201239533534022504592

- News-Medical.net [website on the Internet]FDA approves Gilead’s Stribild to treat HIV-1 infection2012 Available from: http://www.news-medical.net/news/20120828/FDA-approves-Gileade28099s-Stribild-to-treat-HIV-1-infection.aspxAccessed August 26, 2013

- Femail.com.au [website on the Internet]VivaGel new clinical trial commences Available from: http://www.femail.com.au/vivagel-new-clinical-trial-commences.htmAccessed August 26, 2013