Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B and C need immediate worldwide attention as the infection rates are too high. More than 240 million people have chronic (long-term) liver infections. Every year, about 600,000 people die globally due to the acute or chronic consequences of hepatitis B and more than 350,000 people die from hepatitis C-related liver diseases.

Methods

Our study was designed as a case-control, descriptive study. It was conducted through formal interviews by using structured questionnaires. A total of 100 cases were included, with four controls for each case.

Results

This study confirms household contact, history of dental work, history of surgery, sexual contact, and history of transfusion (blood and its components) as the main risk factors which are responsible for the increased prevalence of hepatitis.

Conclusion

The important risk factors, responsible for the high prevalence of hepatitis B and C in our society are household contact, history of dental work, history of surgery, sexual contact, and history of transfusion (blood and its components). The odds ratio of probability for these risk factors are: 4.2 for household contact history, 4.1 for history of dental work, 3.9 for sexual contact, 2.7 for history of surgery, and 2.1 for history of transfusion. Associations of other predictor variables (diabetes status, education level, profession, contact sports, intravenous drug abuse, residence, immunosuppression, and skin tattoos) were not statistically significant.

Introduction

Hepatitis B and C viruses can lead to hepatocellular carcinomaCitation1,Citation2 and cirrhosis-related end-stage liver disease,Citation2,Citation3 which are potentially life-threatening liver diseases.Citation4 Hepatitis B and C need immediate worldwide attention as the infection rates are too high.Citation5 More than 240 million people globally have chronic (long-term) liver infections. Every year, about 600,000 people die because of the acute or chronic consequences of hepatitis B,Citation6 and more than 350,000 people die from hepatitis C-related liver diseases worldwide.Citation7

In the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, an estimated 2%–5% of the general population is chronically infected with hepatitis B.Citation6 Countries with the highest reported prevalence rates of hepatitis C are located in Africa and Asia; areas with lower prevalence rates of hepatitis C include industrialized nations in North America and Northern and Western Europe.Citation8 StudiesCitation9–Citation25 have been conducted in Pakistan to assess the prevalence as well as identify the various risk factors associated with hepatitis B and C. A meta-analysisCitation26 indicates that the prevalence of hepatitis B and C in the general population in Pakistan is 2.4% (range, 1.4%–11.0%) and 3.0% (range, 0.3%–31.9%), respectively.

In most of these studies, however, very few risk factors were included in one study at a time. Many risk factors have been identified worldwide, eg, blood transfusion,Citation27 IV drug abuse,Citation28 profession (health care workers, barbers, etc),Citation29 household contact,Citation30 sexual contact,Citation31 surgical procedures,Citation32 dental procedures,Citation33 immune-compromisedCitation34,Citation35 hemodialysis,Citation36 skin tattoos,Citation37 etc, but the ones responsible for the high prevalence of hepatitis B and C in our cities need to be identified. For this purpose, this study takes into account 13 variables (potential risk factors) all at once to find the association as well as the probability odds ratio.

Research design and methodology

Study design

Our study was designed as a case-control, descriptive study, and was conducted through formal interviews using structured questionnaires. A total of 100 cases (either hepatitis B or hepatitis C positive) were included, with four controls for each case.

Study population

Both outpatients and inpatients of Khyber Teaching Hospital, Peshawar, KPK, Pakistan, were included in the study.

Sampling method

For cases

Inclusion criteria were: aged 18 years and above; diagnosed for either hepatitis B or C through ICT/ELISA. Exclusion criteria were: anyone not in the Khyber Teaching Hospital, Peshawar.

For controls

Inclusion criteria were: aged: 18 years and above; Hepatitis B and C negative. Exclusion criteria were: anyone not in the Khyber Teaching Hospital, Peshawar.

Data collection

Data were collected from respondents (patients) in Khyber Teaching Hospital using a questionnaire over a 5-month period (from October 2013 to February 2014). After verbal consent was obtained, a structured questionnaire was used to conduct face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire had closed-ended questions. It was translated into the mother tongue of the respondent and then retranslated into English, and due corrections were made.

Defining variables

Profession

Based on the established facts, professions were categorized as:

Health care professionals

Barbers

Sewage cleaners

Others

Education level

The respondents were grouped into the following categories based on educational level.

0–4th grade: below primary

5th–9th grade: primary

10th grade: matric

11th–14th grade: above matric

15th grade or above: higher education

Diabetes

Respondents were considered to have diabetes if they had been told by a health care professional that they were diabetic. The criteria for this was to ask the individual respondents themselves and to cross-question them about the time of appearance of the symptoms and when the health care professional had diagnosed their diabetic condition. Accordingly, the respondents were categorized as:

Diabetics

Nondiabetics

Transfusion history

It included transfusion of whole blood or any of its components, eg, fresh frozen plasma.

Accordingly, they were categorized as:

Transfusion history – positive

Transfusion history – negative

Surgical history

In this category, only major surgeries that involve general anesthesia and respiratory assistance were considered.

They were categorized as:

Surgical history– positive

Surgical history – negative

Dental history

Anyone who had done professional cleansing, tooth filling, or tooth extraction, or had undergone dental surgery was considered as having positive dental history.

They were categorized as:

Dental history – positive

Dental history – negative

Contact sports

A contact sport is a sport such as football, hockey, or boxing that involves physical contact between players as part of normal play. Those who had a history of contact sports in the past 5 years were considered as having positive contact sports history.

Intravenous drug abuse

Anyone who disclosed a positive history of drug abuse was then assessed for injection drug abuse, and categorized as:

Injection drug abuse – yes

Injection drug abuse – no

Household contact

If someone had a family member (other than spouse) who was hepatitis B or C positive, then household contact was considered positive; otherwise negative.

Sexual contact

If someone’s spouse was infected with hepatitis B or C, sexual contact was considered positive; otherwise negative.

Rural/urban

Rural areas are places away from cities/towns. On the other hand, towns/cities are called urban areas. Depending on where the respondents lived, they were categorized as:

Those living in places away from cities/towns – rural inhabitants

Those living in cities/towns – urban inhabitants

Sex

People were categorized as either male or female.

Immunosuppression

Respondents were considered immunosuppressed, if they had obvious signs and symptoms of immunosuppression (eg, opportunistic infections) and the following blood counts.

Neutrophils <1,000 cells/µL of bloodCitation38 or

CD4 T-lymphocytes <350 cells/µL of bloodCitation39

Skin tattoos

Tattoos are designs on the skin made with needles and colored ink. The criterion was to ask and then see the skin tattoo objectively.

Statistical analysis

The data were sampled and entered into the SPSS worksheet for analysis. The alpha criterion was set at 0.05 (95% confidence interval [CI]). After constructing a 2×2 contingency table, chi-square without Yates correction was used to find the association between the potential risk factors and hepatitis status.

Whenever the assumption (of expected count being not less than five in each cell) did not meet the chi-square without Yates correction, Fischer’s exact test was used to find the association. Binary logistic regression was used (after meeting the assumptions) to find the influence of each statistically significant predictor variable in terms of the “odds ratio of probability”.

Results

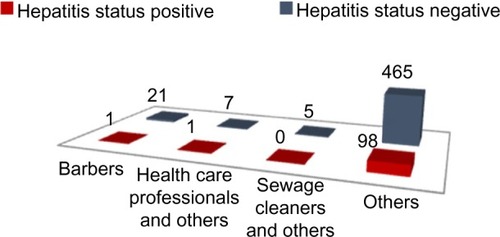

The two-tailed P-value for Fischer’s exact test of profession: “Barber and others” and “hepatitis status” equals 0.061. Thus, the association between professions: “Barber and others” and “hepatitis status” is not considered to be statistically significant (, and ). The two-tailed P-value for Fischer’s exact test of profession: “health care professionals and others” and “hepatitis status” equals 1. Thus, the association between professions: “health care professionals and others” and “hepatitis status” is not considered to be statistically significant (, and ). The two-tailed P-value for Fischer’s exact test of profession: “savage cleaners and others” and “hepatitis status” equals 0.59. Thus, the association between professions: “savage cleaners and others” and “hepatitis status” is not considered to be statistically significant ( and –).

Table 1 Collinearity diagnostics for ruling out related predictor variables

Table 2 Variables in the equation for the binary logistic regression

Table 3 Variables having no association with the Hepatitis B/C as per this study

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on education level: “illiterate and primary” and “hepatitis status” shows chi-square equals 0.69 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals 0.41. Thus, the association between education level: “illiterate and primary” and “hepatitis status” is not considered to be statistically significant. Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on education level: “illiterate and matric” and “hepatitis status” shows chi-square equals 1.74 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals 0.19. Thus, the association between education level: “illiterate and matric” and “hepatitis status” is not considered to be statistically significant (, , and ). Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on education level: “illiterate and above matric” and “hepatitis status” showed chi-square equals 10.05 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals 0.002. Thus, the association between education level: “illiterate and above matric” and “hepatitis status” is considered to be statistically significant (, , and ). Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on education level: “illiterate and higher education” and “hepatitis status” showed chi-square equals 2.61 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals 0.11. Thus, the association between education level: “illiterate and higher education” and “hepatitis status” is not considered to be statistically significant (, , and ).

Table 4 Education level versus hepatitis level

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on diabetes and hepatitis showed chi-square equals 1.42 with 1 degree of freedom and the two-tailed P-value equals 0.23. Thus, the association between diabetes and hepatitis status is not statistically significant (–, and ).

Table 5 Diabetes mellitus status versus hepatitis status

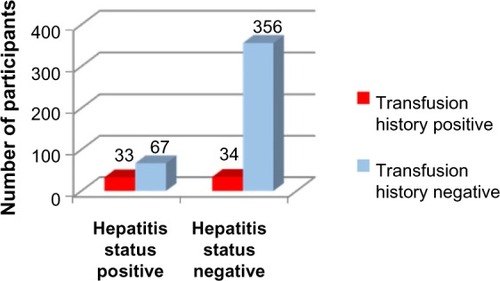

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on transfusion history and hepatitis status shows chi-square equals 29.72 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals less than 0.001. Thus, the association between transfusion history and hepatitis status is considered to be statistically significant with an odds ratio of 3.98 (95% CI: 2.36–6.71) (, , , and ).

Table 6 Significant variables

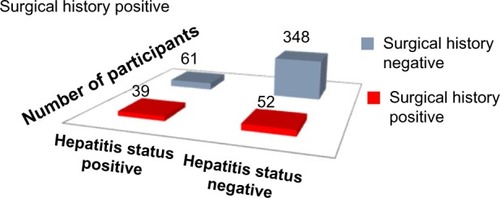

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on surgical history and hepatitis status shows chi-square equals 36.32 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals less than 0.001. Thus, the association between surgical history and hepatitis status is considered to be statistically significant with an odds ratio of 4.28 (95% CI: 2.60–7.03) (, , , and ).

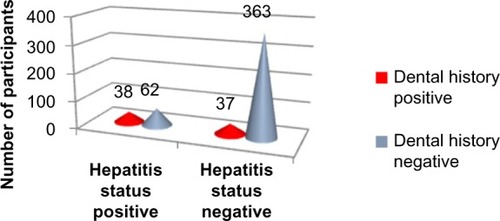

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on dental history and hepatitis status shows chi-square equals 51.86 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals less than 0.001. Thus, the association between dental history and hepatitis status is considered to be statistically significant with an odds ratio of 6.01 (95% CI: 3.55–10.18). (, , , and ).

Table 7 Dental history versus hepatitis status

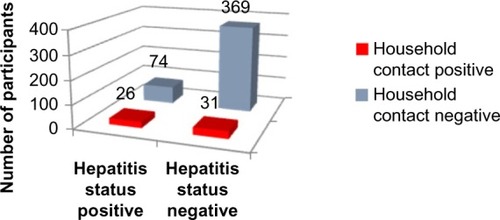

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on household contact and hepatitis status shows chi-square equals 26.38 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals less than 0.001. Thus, the association between household contact and hepatitis status is considered to be statistically significant with an odds ratio of 4.18 (95% CI: 2.35–7.45) (, , , and ).

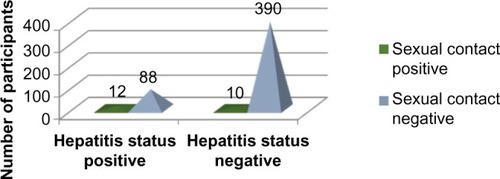

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on sexual contact and hepatitis status shows chi-square equals 17.14 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals less than 0.001. Thus, the association between sexual contact and hepatitis status is considered to be statistically significant with an odds ratio of 5.32 (95% CI: 2.23–12.70) (, , , and ).

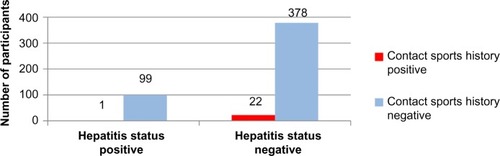

The two-tailed P-value for Fischer’s exact test of contact sports and hepatitis status equals 0.61. Thus, the association between contact sports and hepatitis status is not considered to be statistically significant ( and –).

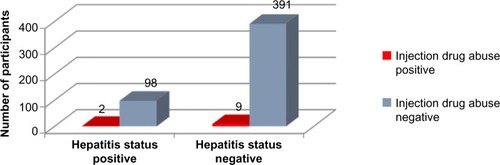

The two-tailed P-value for Fischer’s exact test of injection drug abuse and hepatitis status equals 1. Thus, the association between injection drug abuse and hepatitis status is not considered to be statistically significant ( and –).

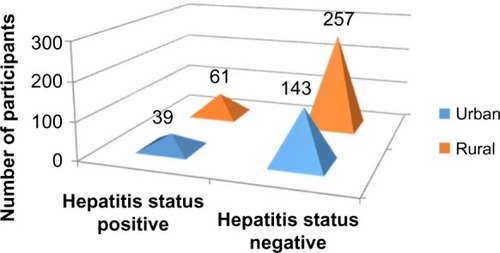

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on residence and hepatitis status shows chi-square equals 0.36 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals 0.55. Thus, the association between residence and hepatitis status is not considered to be statistically significant ( and –).

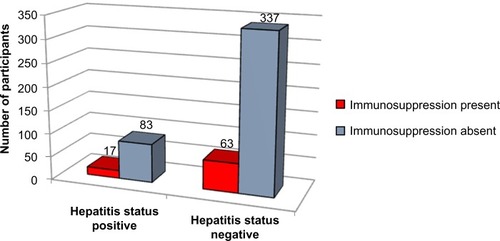

Applying Pearson’s chi-square without Yates correction test on immunosuppression and hepatitis status shows chi-square equals 0.09 with 1 degree of freedom. The two-tailed P-value equals 0.76. Thus, the association between immunosuppression and hepatitis status is not considered to be statistically significant ( and –).

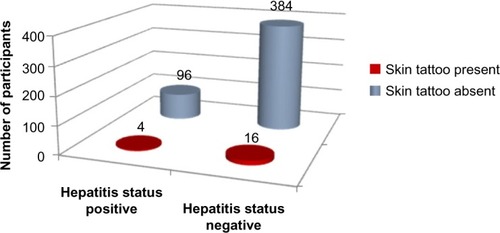

The two-tailed P-value equals 1.0 for Fischer’s exact test of skin tattoos and hepatitis. Thus, the association between skin tattoos and hepatitis status is not considered to be statistically significant ( and –).

Binary logistic regression

As not a single value in “tolerance” is less than 0.10 and not a single value in “variance inflation factor” is greater than 10, it signifies that there is no collinearity between the independent variables. Hence, the assumption of multicollinearity has been met for the binary logistic regression (). The assumption for outliers has also been met.

Based on the results obtained from binary logistic regression, the odds ratios of probability () for the statistically significant predictor variables are as follows:

Dental history: 4.063 (95% CI =2.172–7.603)

Household contact: 4.208 (95% CI =2.109–8.396)

Sexual contact: 3.959 (95% CI =1.372–11.424)

Surgical history: 2.717 (95% CI =1.450–5.091)

Transfusion history: 2.114 (95% CI =1.085–4.119)

Discussion

We found that in our society, the important risk factors for hepatitis B and C are household contact, history of dental work, history of surgery, sexual contact, and history of transfusion (blood and its components).

The individual risk factor was stratified to know the degree of its influence using binary logistic regression. It was found that the odds ratio of probability for household contact is 4.2 (this means that if a person has a history of household contact, then he is 4.2 times more likely to have the disease as compared with a person without a history of household contact). For history of dental work, sexual contact, history of surgery, and history of transfusion, the odds ratios of probability are 4.1, 3.9, 2.7, and 2.1, respectively. In the past, studiesCitation14–Citation18,Citation21,Citation23,Citation26 were conducted in Pakistan to find the prevalence of disease or to find the association of a single risk factor.Citation9–Citation13,Citation20–Citation22,Citation24,Citation25 However, very few studiesCitation26 have been conducted in Pakistan to include many possible risk factors in one study, even then the individual risk factor was not stratified (to find the degree of its influence).

We took many predictor variables all at once and identified the risk factors for our region. Based on the results, a targeted approach can be adopted in health prevention implementation. The predictive ability of our logistic model is 83%, which makes it a very good model.

Our study had funding limitations, and data collection was done by interns and final-year students along with their busy schedules. Because of deficiencies in the medical records, hepatitis B-positive patients and hepatitis C-positive patients were not separated during the analysis, and both were labeled as hepatitis positive. Because of the strict social norms in the city, data on sexual behavior (use or not of condoms, number of sexual partners) were not collected.

This study confirms household contact, history of dental work, history of surgery, sexual contact, and history of transfusion (blood and its components) as the main risk factors responsible for the increased prevalence of hepatitis. Therefore, all necessary precautions (eg, screening before dental and surgical procedures) should be taken not only at the individual level but also at the level of the whole population, and awareness should be increased in the general population to ensure the safety of precious lives.

Conclusion

The important risk factors responsible for the high prevalence of hepatitis B and C in our society are household contact, history of dental work, history of surgery, sexual contact, and history of transfusion (blood and its components). The odds ratio of probability for these risk factors are: 4.2 for household contact history, 4.1 for history of dental work, 3.9 for sexual contact, 2.7 for history of surgery, and 2.1 for history of transfusion. Associations of other predictor variables (diabetes status, education level, profession, contact sports, IV drug abuse, residence, immunosuppression, and skin tattoos) were not statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Khyber Teaching Hospital authorities for giving us permission to do this study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SundquistKSundquistJJiJRisk of hepatocellular carcinoma and cancers at other sites among patients diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in SwedenJ Med Virol2014861182224038002

- ShrivastavaSMukherjeeARayRBHepatitis C virus infection, microRNA and liver disease progressionWorld J Hepatol20135947948624073299

- ZhongLHJiangYMLouGQThe relationship between serum HBsAg levels and liver inflammation and fibrosis in patients with chronichepatitis BZhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi2013272929424044209

- PapadakisMAMcPheeSJRabowMWCurrent Medical Diagnosis and TreatmentNew York, NYMcGraw Hill2013

- World Health OrganizationImmunizations, vaccines and biologicals Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/topics/hepatitis/en/Accessed May 20, 2015

- World Health OrganizationHepatitis B Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/index.htmlAccessed May 20, 2015

- World Health OrganizationHepatitis C Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/index.htmlAccessed May 20, 2015

- ShepardCWFinelliLAlterMJGlobal epidemiologyLancet Infect Dis2005555856716122679

- KhattakMFSalamatNBhattiFAQureshiTZSeroprevalence of hepatitis B, C and HIV in blood donors in northern PakistanJ Pak Med Assoc20025239840212532573

- AkhtarSYounusMAdilSHassanFJafriSHEpidemiologic study of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in male volunteer blood donors in Karachi, PakistanBMC Gastroenterol200552616086833

- AbdulMSNananDSabirSAltafAKadirMHepatitis B and C infection in first-time blood donors in Karachi – a possible subgroup for sentinel surveillanceEast Mediterr Health J20061273574117333817

- SultanFMehmoodTMahmoodMTInfectious pathogens in volunteer and replacement blood donors in Pakistan: a ten-year experienceInt J Infect Dis20071140741217331775

- LubySPQamruddinKShahAAThe relationship between therapeutic injections and high prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Hafizabad, PakistanEpidemiol Infect19971193493569440439

- KhokharNGillMLMalikGJGeneral seroprevalence of hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infections in populationJ Coll Physicians Surg Pak20041453453615353136

- AbbasZShaziLJafriWPrevalence of hepatitis B in individuals screened during a countrywide campaign in PakistanJ Coll Physicians Surg Pak20061649749816827971

- MirzaIAKazmiSMJanjuaANFrequency of hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-HCV in young adults – experience in southern PunjabJ Coll Physicians Surg Pak20071711411517288863

- ParkerSPKhanHICubittWDDetection of antibodies to hepatitis C virus in dried blood spot samples from mothers and their offspring in Lahore, PakistanJ Clin Microbiol1999372061206310325381

- AslamMAslamJSeroprevalence of the antibody to hepatitis C in select groups in the Punjab region of PakistanJ Clin Gastroenterol20013340741711606859

- MujeebSAShahabSHyderAAGeographical display of health information: study of hepatitis C infection in Karachi, PakistanPublic Health200011441341511035468

- AkhtarSYounusMAdilSJafriSHHassanFHepatitis C virus infection in asymptomatic male volunteer blood donors in Karachi, PakistanJ Viral Hepat20041152753515500553

- MuhammadNJanMAFrequency of hepatitis C in Buner, NWFPJ Coll Physicians Surg Pak200515111415670516

- PashaOLubySPKhanAJShahSAMcCormickJBFisher-HochSPHousehold members of hepatitis C virus-infected people in Hafizabad, Pakistan: infection by injections from health care providersEpidemiol Infect199912351551810694166

- AkhtarSMoatterTAzamSIRahbarMHAdilSPrevalence and risk factors for intrafamilial transmission of hepatitis C virus in Karachi, PakistanJ Viral Hepat2002930931412081609

- AkhtarSMoatterTIntra-household clustering of hepatitis C virus infection in Karachi, PakistanTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg20049853553915251402

- QureshiHArifAAhmedWAlamSEHCV exposure in spouses of the index casesJ Pak Med Assoc20075717517717489523

- AliSADonahueRMQureshiHVermundSHHepatitis B and hepatitis C in Pakistan: prevalence and risk factorsInt J Infect Dis200913126

- GresensCJHollandPVCurrent risks of viral hepatitis from blood transfusionsJ Gastroenterol Hepatol19981344434499641313

- TofigiHGhorbaniMAkhlaghiMIncidence of hepatitis B and HIV virus at cadaver of IV drug abusers in TehranActa Med Iran2011491596321425074

- AfridiAAKumarASayaniRNeedle stick injuries – risk and preventive factors: a study among health care workers in tertiary care hospitals in PakistanGlob J Health Sci201354859223777725

- BrasilLMda FonsecaJCde SouzaRBBragaWSde ToledoLMPrevalence of hepatitis B virus markers within household contacts in the State of AmazonasRev Soc Bras Med Trop200336556557014576869

- TahanVKaracaCYildirimBSexual transmission of HCV between spousesAm J Gastroenterol200510082182415784025

- HumaQArifARiazKAlamSEAhmedWMujeebSMDetermination of risk factors for hepatitis B and C in male patients suffering from chronic hepatitisBMC Res Notes2009221219852780

- MahboobiNPorterSRKarayiannisPAlavianSMDental treatment as a risk factor for hepatitis B and C viral infectionJ Gastrointestin Liver Dis2013221798623539395

- GoossensNNegroFReactivation of hepatitis B associated with immunosuppressionRev Med Suisse2013939615661568157124066463

- ZachouKSarantopoulosAGatselisNKHepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B virus surface antigen negative patients receiving immunosuppression: a hidden threatWorld J Hepatol20135738739223898372

- FonteneleAMFilhoNSFerreiraASOccult hepatitis B in patients on hemodialysisAnn Hepatol201312452753123813129

- CarneyKDhallaSAytamanATennerCTFrancoisFAssociation of tattooing and hepatitis C virus infection: a multicenter case-control studyHepatology20135762117212323315899

- Clinical Center, National Institute of Health Available from: http://www.cc.nih.gov/ccc/patient_education/pepubs/cbc.pdfAccessed: June 24, 2015

- US Department of Health and Human Services Available from: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/education-materials/fact-sheets/print/21/52/0/0Accessed May 20, 2015