Abstract

The pharmacoenhancement of plasma concentrations of protease inhibitors by coadministration of so-called boosters has been an integral part of antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) for 1.5 decades. Nearly all HIV protease inhibitors are combined with low-dose ritonavir or cobicistat, which are able to effectively inhibit the cytochrome-mediated metabolism of HIV protease inhibitors in the liver and thus enhance the plasma concentration and prolong the dosing interval of the antiretrovirally active combination partners. Therapies created in this way are clinically effective regimens, being convenient for patients and showing a high genetic barrier to viral resistance. In addition to ritonavir, which has been in use since 1996, cobicistat, a new pharmacoenhancer, has been approved and is widely used now. The outstanding property of cobicistat is its cytochrome P450 3A-selective inhibition of hepatic metabolism of antiretroviral drugs, in contrast with ritonavir, which not only inhibits but also induces a number of cytochrome P450 enzymes, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, P-glycoprotein, and other cellular transporters. This article reviews the current literature, and compares the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of both pharmacoenhancers and discusses the clinical utility of cobicistat in up-to-date and future HIV therapy.

Introduction

The introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in 1996 greatly decreased the overall morbidity and mortality of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) worldwide.Citation1,Citation2 As the eradication of HIV after infection and a cure is still not possible, long-term viral efficacy, safety, tolerability, and convenience are the major goals of probable lifelong HIV treatment. The disadvantages of long-term treatment related to protease inhibitor (PI)-based cART are multiple, in particular metabolic disordersCitation3 and cardiovascular disease,Citation4–Citation6 and have changed the view of clinicians on such regimens. Given that cART has to be taken by patients over decades, drugs are not only chosen because of their antiretroviral potency but also assessed for their possible long-term side effects, pill burden, and potential for interactions with other commonly taken drugs. In particular, the growing number of patients older than 60 years of age, family planning or pregnant women or, most vulnerable, children are in need of effective and safe long-lasting cART.Citation7,Citation8 Further, treatment of hepatitis coinfection with new PIs for hepatitis C virus, management of metabolic syndrome, and the growing number of salvage patients has drawn attention to the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions within such regimens.Citation9–Citation13 One key question is whether the principle of boosting or the booster itself causes some of the long-term side effects.

Current HIV therapy regimen

Almost all PIs and non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) used to treat HIV, along with maraviroc, are metabolized by intestinal and hepatic cytochrome oxidases, in particular P450 (CYP)3A. Administered orally as single drugs, PIs in particular have low systemic exposure and short half-lives. In 1996, it was shown that ritonavir, an HIV-1 PI with marked antiviral activity, was able to inhibit CYP3A isoenzymesCitation14 and thus enhance the plasma exposure of combination partners such as indinavir, saquinavir, or lopinavir, ie, the first-generation HIV PIs. Today, ritonavir is administered at low subtherapeutic doses of 100 mg as a cART-boosting agent together with a second-generation PI, ie, atazanavir or darunavir.Citation15 Although widely used, coadministration with ritonavir causes a number of problems; it is able to inhibit or induce other CYP subfamilies, eg, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP1A2,Citation14 urunosyl-glucuronyl-transferase (UGT), and transmembrane drug transporters, eg, OCT and ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein), so is responsible for a large number of drug-drug interactions. Even the low dose of 100 mg once daily can cause unfavorable, in particular gastrointestinal, side effects over a long time.

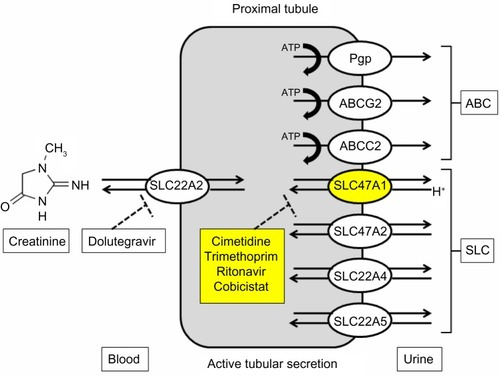

Hence, other HIV-1 PI-boosting drugs have been searched for, and a new entity, cobicistat, was finally approved in 2012. The unique pharmacological property of cobicistat is its selective inhibition of CYP3A, the renal transmembrane transporter (MATE-1) and intestinal ABCB1 at low concentrations (0.034 μmol).Citation16,Citation17 Cobicistat also has unwanted side effects, albeit to a lesser extent than ritonavir, and its potential to decrease creatinine clearance in particular has been discussed extensively in the recent past. Therefore, this review of cobicistat as a pharmacoenhancer pays special attention to its mechanisms of action, safety profile, and clinical utility in the long-term perspective.

Pharmacological properties of HIV pharmacoenhancers

Mechanisms of action

Ritonavir was designed in the early 1990s as an HIV PI in order to inhibit the dissection of viral protein precursors of HIV-1-infected cells by viral proteases, thereby stopping the production of viral particles and subsequent infection of uninfected cells.Citation18 Initially, 600 mg ritonavir was administered orally twice daily together with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (mainly epivir, zidovudine, or didanosine).Citation19,Citation20 In combination with other early first-generation PIs (saquinavir,Citation21,Citation22 indinavirCitation23,Citation24) in patients failing therapy with ritonavir alone, plasma PI concentrations of the coadministered drugs were much higher than previously expected. Patients could decrease the dosing frequency and the dose of both HIV PIs and, even more important, such combinations could overcome previously archived viral resistance against single PIs.Citation21 Today, ritonavir is formulated as a pharmacoenhancer at a low dose of 100 mg.

Cobicistat on the other hand is antiretrovirally inactive and selectively inhibits CYP3A isoenzymes (but not other cytochromes or UGT), and also a number of transmembrane drug transporters at different blood-target tissue barriers. Cobicistat is coformulated into fixed-dose combinationsCitation12 in order to reduce pill burden and improve adherence with once-daily HIV regimens,Citation25–Citation29 but is also available as a single agent (Tybost®).

Several Phase I studies have shown the effective pharmacoenhancing potential of cobicistat. In the first studies in healthy volunteers, the pharmacokinetic parameters of elvitegravir following administration of a fixed-dose combination with elvitegravir, emtricitabine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (DF), and cobicistat were similar to those of ritonavir-boosted elvitegravir.Citation30 In addition, plasma concentrations of the HIV PI atazanavir were comparable between regimens containing atazanavir/ritonavir (300/100 mg) and those containing atazanavir/cobicistat (300/150 mg).Citation31 Further, the comparable efficacy and safety of cobicistat versus ritonavir when taken together with atazanavir/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF (ATV/FTC/TDF 300/200/245 mg) were confirmed in cART-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients.Citation17,Citation32

The pharmacokinetic parameters of darunavir following coadministration of once-daily darunavir 800 mg with cobicistat 150 mg, either as single agentsCitation33 or as two candidate fixed-dose combinations (G003 and G004),Citation34 were similar to those of darunavir/ritonavir (800/100 mg) administered once daily, except for lower plasma darunavir concentrations after 24 hours with darunavir/cobicistat.Citation23,Citation24

Drug-drug interactions of PIs

The potential for pharmacokinetic interactions is always a major concern of cART for clinicians. Not only PIs, but also non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs, efavirenz, etravirine, rilpivirine, and nevirapine), the CCR5 inhibitor maraviroc, and the new integrase inhibitor elvitegravir, are metabolized in part by the same hepatic CYP oxidases and are consequently vulnerable to changes in CYP metabolic activity. Boosting of HIV PIs with ritonavir 100 mg or 200 mg has been described extensively in the past,Citation35–Citation39 but ritonavir also affects CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP1A2, and these effects can be quite variable; starting with marginal effects in combination with lopinavir,Citation40,Citation41 it can result in considerable effects if coadministered with atazanavir/saquinavir.Citation42 In the contrary, the lopinavir/ritonavir combination itself is vulnerable to inducers of CYP3A metabolism, in that nevirapine and efavirenz, for example, both substantially decrease the plasma exposure of lopinavir and ritonavir when coadministered.Citation43–Citation45

In contrast, the new booster cobicistat was selected from a number of progenitors because of its selective inhibition of CYP3A. It inhibits human hepatic and intestinal CYP3A activity at a very low inhibitory concentration (IC), and the Kl and kinact are comparable with those of ritonavir. Like ritonavir, cobicistat is a substrate for hepatic CYP3A metabolism. However, unlike ritonavir, cobicistat is only a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 (at an IC50 of 9.2 μmol/L) and does not affect CYP1A2, CYP2C9, or CYP2C19 (IC50 >25 μmol/L).

In contrast with ritonavir, which induces early phase I cytochrome expression after therapy is initiated, as well as phase II UGT activity, inducing its own metabolism and that of coadministered drugs for up to 2 weeks until a steady state is reached, cobicistat has no such influence in vivo.

Cobicistat versus ritonavir

Both ritonavir and cobicistat given at low doses (100 mg and 50 mg, respectively) were compared during the pivotal trials for cobicistat. Their efficacy was shown to be comparable; however, the safety aspects showed differences between the two drugs. Lipodystrophy or the potential induction of insulin resistance when ritonavir is combined with other prevalent PIs during long-term cART has not been seen with cobicistat so far, albeit the period of experience with cobicistat as a cART combination partner is much shorter than that with ritonavir, so its potential to induce lipodystrophy may not be fully appraised as yet. On the other hand, cobicistat significantly increased serum creatinine concentrations during the early phase of treatment and raised concerns about its potential renal toxicity. The two drugs share a similar potential for gastrointestinal toxicity, although a lower risk for diarrhea has been found for cobicistat. These issues, along with other side effects presented, are discussed in the following sections.

Pharmacokinetics, safety, and pharmacodynamics of cobicistat

Phase I pharmacokinetics (GS-216-0101)

The pharmacokinetics of cobicistat were investigated for the first time in 84 healthy male volunteers who received cobicistat 50, 100, 200, 300, and 400 mg in a sequential study with escalating single doses of cobicistat and in 72 volunteers who took repeated doses of 50, 100, 200, and 300 mg at steady state. Steady-state pharmacokinetics showed both dose-dependent and time-dependent changes in the pharmacokinetic parameters of cobicistat, leading to an up to 47-fold increase in cobicistat exposure and a 95% decrease in clearance after multiple dosing with 50–300 mg (P<0.001, analysis of variance, see ).

Table 1 Pharmacokinetic parameters of cobicistat at steady state (GS-216-0101 study)

Three subjects in each group received ritonavir 100 mg or placebo in order to evaluate and compare the inhibitory potential of either ritonavir or cobicistat on concomitantly administered midazolam, which is known to be a selective CYP3A substrate. Clearance of midazolam was reduced by 89% when coadministered with cobicistat, which was comparable with that seen for 100 mg of ritonavir (see ). Twelve subjects discontinued the study treatments, but only one stopped early due to a drug-related adverse event.

Table 2 Clearance of the CYP3A substrate midazolam, either combined with cobicistat or alone, reported as the GMR and 90% CICitation30,Citation72

Phase I safety (GS-216-0121)

Thirty-six HIV-negative adult volunteers took cobicistat 150 mg plus ritonavir placebo (n=12), ritonavir 100 mg plus cobicistat placebo (n=12), or ritonavir placebo plus cobicistat placebo (n=12) for 7 days to investigate and quantify the effect of each drug on kidney function. In addition, 18 volunteers with moderately impaired renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate [GFR] 50–79 mL/min) took cobicistat 150 mg for 7 days without placebo. A 1,500 mg bolus of iohexol, a substance that is almost 100% filtered at the glomerulus and unlike creatinine is not secreted in the kidney tubules, thus representing the reference substance for the real change in GFR in humans, was injected intravenously on days 0, 7, and 14 (follow-up) and the iohexol plasma concentration was measured. The clearances of ritonavir and cobicistat were calculated at day 7, and the GFR was calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula (GFRCG).Citation46 Subsequently, it was shown that the estimated GFR changed significantly (−9.90 mL/min, P<0.05), but not the apparent GFRCG (−2.70 mL/min). The group with reduced renal function also showed a statistically significant reduction in estimated GFR (−11.9 mL/min; P<0.001) and apparent GFRCG (−3.60 mL/min), whereas the administration of ritonavir did not cause any changes in the GFR in either group.Citation46

Phase II pharmacodynamics and safety (GS-216-0105)

In this randomized controlled clinical study, the safety and efficacy of cobicistat-boosted (n=50) versus ritonavir-boosted (n=29) atazanavir (300 mg) was investigated in HIV-1-infected adults through 48 weeks on therapy. The rates of grade 1–4 adverse events seen with cobicistat (36%) and ritonavir (48%) were comparable. Only two patients discontinued the cobicistat-based therapy regimen due to adverse events (vomiting, rash) and one patient stopped taking ritonavir because of ocular icterus, most likely related to taking ritonavir-boosted atazanavir. Approximately 5% of patients in each study group developed grade 2–4 laboratory abnormalities, including increased total bilirubin (likely caused by inhibition of bilirubin-metabolizing UGT1A1 by atazanavir), serum amylase, total cholesterol, and creatine kinase concentrations, decreased serum phosphate levels, and hematuria. Small to moderate changes in total, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were comparable between the two study groups. Further, mean estimated GFR decreased by 13.3 mL/min in patients taking cobicistat and by 13.8 mL/min in those receiving ritonavir as part of their cART.Citation17,Citation47

Pharmacodynamics and safety (GS-236-0104)

GS 236-0104 was a randomized, controlled, Phase II clinical trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of elvitegravir 150 mg/cobicistat 150 mg/emtricitabine 200 mg/tenofovir-DF 245 mg in a fixed-dose tablet (“QUAD”, marketed as Stribild®, n=48) versus efavirenz 600 mg/emtricitabine 200 mg/tenofovir-DF 245 mg as a fixed-dose combination (Atripla®, n=23).

At baseline, patients in both groups were of comparable mean age (36 versus 35 years), mean viral load (HIV-RNA polymerase chain reaction 4.59 log10 versus 4.58 log10 copies/mL), and median CD4 cell count (354 versus 436 cells/mm3).

The incidence of drug-related adverse events through 48 weeks on therapy was also comparable in both groups (46% versus 57%). Two patients in either arm experienced grade 3–4 adverse events, without discontinuing the study. However, patients taking the QUAD tablet experienced significantly fewer central nervous system (CNS) symptoms compared with patients taking efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir-DF (17% versus 43%, P=0.02) and fewer psychiatric symptoms (10% versus 26%). One patient on efavirenz-containing therapy stopped treatment due to suicidal ideation.Citation16 In this trial, no grade 3–4 laboratory adverse events were reported, and cholesterol/triglyceride increases did not exceed grade 1–2.Citation16

Again, the estimated GFRCG decreased, being 19.7 mL/min in patients taking cobicistat versus 5.5 mL/min in patients taking the unboosted therapy regimen. However, none of the study patients stopped early due to changes in the estimated GFR or related serum creatinine.Citation16

Phase I kidney safety study

Subsequently, a Phase I trial was conducted to evaluate the effects of cobicistat on GFR. A group of healthy volunteers took cobicistat or placebo (n=12 in each group) for 1 week with a washout period of 7 days between the study medications. Again, estimated GFR decreased when cobicistat was taken, but returned to baseline after intake of the study drug was stopped. A parallel group of volunteers received iohexol, the reference compound for detection of changes in GFR. However, the iohexol clearance was not affected at all.Citation46

The investigators concluded that there was a cobicistat-related decrease in renal SLC22A2 or SLC47A1 transmembrane transporter activity, which is part of the tubular excretion pathway for creatinine. Logically, this effects an increase of serum creatinine concentrations, distorting the estimation of GFR by the Cockcroft-Gault formula, but not the real GFR, thus showing a nonexistent effect on glomerular filtration caused by cobicistat.Citation30

Phase III safety and efficacy

GS-1020

GS-1020, a controlled Phase III clinical study, evaluated the safety and efficacy of elvitegravir 150 mg/cobicistat 150 mg/emtricitabine 200 mg/tenofovir-DF 245 mg as a fixed-dose combination (Stribild, n=348) versus efavirenz 600 mg/emtricitabine 200 mg/tenofovir-DF 245 mg (fixed-dose combination, Atripla, n=352). At baseline, patients in both study groups were of mean age 38 years, with a similar viral load (HIV-RNA polymerase chain reaction 4.75 log10 versus 4.78 log10 copies/mL) and comparable median absolute CD4 count (391 versus 382 cells/mm3). The proportions of male (88% versus 90%) and asymptomatic HIV-infected patients (83% versus 84%) were also comparable at baseline between the groups, and representative of the typical treatment-naïve patient starting first-line therapy according to the majority of the international guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-infected adults. However, the proportion of female patients was not representative of the proportion of women infected with HIV-1 worldwide, which ranges from 20% in Europe to 60% in sub-Saharan Africa. The proportions of patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus were 6% and 7%, respectively.

The primary study endpoint compared the number of patients having an undetectable viral load with a cutoff of <50 copies/mL at week 48. The results were reported at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in 2012 by Sax et alCitation48 and published by Wohl et al.Citation49 Meanwhile, the data to 96 weeks have been reported and shown stable results.Citation50

The drug-related adverse event rate revealed no differences between the study arms with regard to headache, depression and fatigue, upper respiratory infections, and diarrhea. In contrast, abnormal dreams, insomnia, and dizziness together with rash had a much higher incidence during the intake of efavirenz, whereas nausea was reported more often in the Stribild arm. Comparable proportions of patients (3% versus 4%) stopped taking their study medication. In the efavirenz arm, 3% of patients stopped their study medication, mainly due to CNS-related adverse events, and 4% stopped taking Stribild, mainly (1.4% versus 0%) due to alterations in renal function.Citation49

However, the grade 3–4 laboratory adverse event rate, especially elevation of serum creatine kinase, was higher with efavirenz (11%) than with Stribild (5%). The remaining grade 3–4 adverse events did not reveal marked differences between the study groups.

Although data on glomerular filtration were not shown in this poster presentation (DeJesus et al, Seattle, WA, USA),Citation51 one graph again showed a median serum creatinine increase by 0.14 mg/dL through week 48 on treatment with Stribild, which is in accordance with previous results from the Phase II studies.Citation16

GS-103

GS-103, a controlled Phase III clinical trial compared the safety and efficacy of atazanavir boosted with cobicistat (n=353) versus ritonavir (n=355) in HIV-1-infected patients, both receiving emtricitabine/tenofovir-DF as a nucleotide backbone, over 48 weeks on treatment. At baseline, patients in both study arms had a comparable mean age (38 versus 39 years), mean baseline HIV viral load (4.88 log10 versus 4.86 log10 copies/mL), and median absolute CD4 cell count (364 versus 375 cells/mm3). At baseline, the majority of patients were male (92% and 89%) with asymptomatic HIV-1 infection (81% and 83%), again under-representing the higher rate of HIV-infected women worldwide.Citation52 The proportions of patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus were 5% and 6%, respectively.

Again, the primary study endpoint compared the number of patients having an undetectable viral load with a cutoff of <50 copies/mL at week 48. The results of this study have been published and show comparable results up to week 144.16,48,51,55,–57

The drug-related adverse event rate revealed no differences between the study arms with regard to headache, fatigue, upper respiratory infections, diarrhea, and nausea. Interestingly, the ocular icterus which is commonly related to boosted atazanavir treatment showed a significantly lower incidence in the cobicistat arm (1% versus 14%). In the cobicistat arm, 4% of all patients stopped taking their study medication, mainly because of gastrointestinal side effects, and 5% discontinued in the ritonavir arm, mainly because of icterus, jaundice, or dizziness.

The proportion of all grade 3–4 laboratory adverse events (in particular elevations in creatine kinase, AST, ALT, and amylase) were comparable between the study arms, whereas hematuria (4% versus 2%) and hyperbilirubinemia (1% versus 58%, P<0.001) were different between the treatment groups.

With regard to kidney function, the authors showed nearly similar median serum creatinine increases of 0.12 versus 0.08 mg/dL for both groups through the 48-week treatment period. Only 0.3% of patients in each study arm stopped treatment early due to renal adverse events.

Although the mean changes in cholesterol revealed statistically significant differences between the two study arms (P<0.001), only 2%–4% of patients in each study group revealed a cholesterol change of grade 2 or more. Despite the differences in total cholesterol, the high/low-density lipoprotein ratio remained roughly the same through week 144, which puts the clinical relevance of such changes into a restricted perspective.Citation53

Interestingly, results from a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry analysis performed in a subgroup of 120 patients at weeks 24 and 48 showed no statistically significant differences between cobicistat-containing and ritonavir-containing treatment: however, a loss of bone mineral density of 2.45% versus 3.46% (P=0.25) at the spine and 2.87% versus 3.59% (P=0.12) at the hip, with fracture numbers of three versus six (P=0.51) in the study arms at week 48 are not negligible, and most probably related to tenofovir-DF and not to cobicistat, ritonavir, or atazanavir.

Drug-related side effects

A comparison of the drug-related adverse event rates in the two Phase II studies of Stribild versus Atripla and cobicistat versus ritonavir did not indicate marked differences in the proportions of all grade 1–4 adverse events ( and ). CNS symptoms were not related to either of the pharmacoenhancers, but to efavirenz. The incidence of diarrhea was expectedly highest in patients taking atazanavir/ritonavir. Again, only marginal differences were detected in both Phase III pivotal trials for all grade 3–4 adverse events, except for the expected much higher rate of hyperbilirubinemia and ocular icterus in the atazanavir-containing arm of GS-103 and CNS-related adverse events with Atripla when compared with Stribild in the GS-102 study. Decreases in bone mineral density were most probably due to taking tenofovir-DF as part of the antiretroviral backbone in Phase III studies.

Table 3 Summary of adverse events under treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy containing cobicistat from different Phase II studiesCitation16,Citation56

Table 4 Summary of adverse events under treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy containing cobicistat from different Phase III studies

Treatment-related laboratory abnormalities

The summary of drug-related grade 2–4 laboratory adverse events are reported if those occurred in more than 5% of patients or in another sense revealed distinct differences between either Stribild or Atripla and cobicistat-boosted versus ritonavir-boosted therapy regimens ( and ). The cobicistat-related estimated GFRCG reductions must be appraised, taking into account inhibition of the transmembrane transport pathway of creatinine excretion from blood through the tubular cells into the urinary tract by SLC47A1. Accordingly, it cannot be concluded that the changes in estimated GFR of the first cobicistat presentations shown in 2010Citation56 proved that GFR decreases in reality. In particular, the findings of a subsequent study of the distinct renal effects of cobicistat that was conducted parallel to the Phase II pivotal trials could explain the mechanisms causing the increased serum creatinine in patients, but also confirm that cobicistat does not influence the real GFR in humans over a longer period of time.Citation57

Table 5 Summary of grade 2–4 treatment-related laboratory abnormalities occurring in more than 5% of any treatment arm from different Phase II cobicistat studiesCitation56

Table 6 Summary of grade 2–4 treatment-related laboratory abnormalities occurring in more than 1% of any treatment arm from different Phase III cobicistat studies

The high rate of increased serum bilirubin, followed by jaundice and ocular icterus seen with the cobicistat-boosted and ritonavir-boosted atazanavir regimens were most probably caused by inhibition of metabolism of bilirubin via UGT1A1 by boosted atazanavir, but not by one of the boosters themselves. Differences in the increase of serum bilirubin were not detected on comparison of the safety results in both study arms, which means that a direct impact of either pharmacoenhancer on serum bilirubin concentrations is not likely and can be verified by previous publications on atazanavir which show a genetic but no atazanavir dose/exposure-dependent influence on UGT-mediated bilirubin metabolism.Citation58

STRATEGY studies

The two STRATEGY trials were published recently and showed that patients who are on stable NNRTI-based or PI-based cART with a viral load <50 copies/mL for more than 6 months can switch to Stribild maintenance therapy.

In the randomized, open-label, Phase IIIb STRATEGY-NNRTI study,Citation59 290 patients switched from either efavirenz-based (83%) or nevirapine-based cART (17%) to elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir/emtricitabine, whereas 143 patients kept taking their former regimen; at week 48, 93% and 88%, respectively, maintained plasma viral loads <50 copies/mL (P=0.066). There was no treatment-emergent resistance in either group and safety events leading to discontinuation were uncommon. The safety results were comparable with those of the GS-102 study.

In the randomized, open-label Phase IIIb STRATEGY-PI study, patients who were on stable cART with either darunavir-based or atazanavir-based cART (40% each) switched to Stribild (elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir/emtricitabine), whereas 20% of patients kept taking their former regimen. The key eligibility criteria included no history of virological failure, no resistance to emtricitabine or tenofovir, and creatinine clearance ≥70 mL/min. After 48 weeks on the new therapy, 93.8% of 290 patients in the switch groups maintained a viral load <50 copies/mL versus 87.1% of 139 in the nonswitch group (P=0.025). The stated statistical superiority of switching was mainly due to the higher proportion of patients in the nonswitch group stopping treatment for nonvirological reasons, such as side effects, eg, icterus with atazanavir/ritonavir or gastrointestinal effects with darunavir/ritonavir.Citation60

Renal and hepatic impairment

Data on the use of cobicistat in patients with hepatic impairment have also been published and indicate no clinically relevant changes in the pharmacokinetics of cobicistat-boosted elvitegravir in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment comparable with Child-Pugh status B. While the elvitegravir exposure was moderately enhanced in comparison with that in patients without hepatic impairment, the geometric mean (90% confidence interval [CI]) cobicistat AUC and peak plasma concentration ratios were 99.8 (76.0–131) and 86.1 (65.4–113) for patients with hepatic impairment. Hence, cobicistat can be administered in patients with liver impairment without concerns regarding safety and efficacy.Citation61

Custodio et al presented data from two randomized crossover cohorts of 32 and 14 healthy volunteers in Amsterdam 2013, where they could show that in the case of combining 150 mg cobicistat and 300 mg tenofovir (245 mg tenofovir-DF), the tenofovir mean (90% CI) maximum plasma concentration is increased 55% (34–78) compared to tenofovir mean plasma concentrations without coadministration of cobicistat. The mean (90% CI) area under the curve (AUC) and trough concentrations for tenofovir were increased 23% (16–39) and 25% (16–36), respectively. The authors discussed how cobicistat inhibits intestinal P-glycoprotein efflux and thus enhances the bioavailability of tenofovir-DF. Although a direct correlation between enhanced tenofovir-plasma exposure and decreased renal function has not been shown as yet, patients taking a combination of tenofovir and cobicistat should at least be monitored closely for renal function.Citation62

If cobicistat is taken by patients with mild renal impairment, and renal function deteriorates with GFR falling below 50 mL/min or serum phosphate levels decreasing to 0.32 mmol/L (1.0 mg/dL), cobicistat should be stopped, according to its labeling. If combined with antiretrovirals that have to be dose-adjusted in the event of renal impairment (eg, darunavir, atazanavir), cobicistat should be stopped when the GFR falls below 70 mL/min. The same counts for a phosphate concentration falling below <0.48 mmol/L (1.5 mg/dL). If a patient takes cobicistat without such combination partners, clinical routine renal function tests should be performed weekly if the GFR drops to <70 mL/min.

Cobicistat as part of Stribild should not be taken by patients who have recently taken or are still taking nephrotoxic substances.Citation63

Drug interactions

The renal effects of cobicistat were discussed earlier in this paper. Regarding inhibition of cytochrome oxidases, cobicistat 150 mg has an effect on hepatic CYP3A isoenzymes comparable with that seen with ritonavir 100 mg. Cobicistat is a substrate and a potent CYP3A inhibitor, whereas its inhibition of CYP2D6 is restricted. It also inhibits cellular transporters such as ABCB1, BCRP, OATP1B1, and OATP1B3, which are located in various blood-tissue barriers and are part of the renal tubular excretion pathways of several drugs. As a consequence, cobicistat could enhance the plasma concentrations of a number of drugs used widely in clinical settings, such as calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), antiarrhythmics, sedative hypnotics, so-called lifestyle drugs used for erectile dysfunction and alopecia, corticosteroids, norgestimate, and antiretrovirals. Cobicistat decreases the steady-state clearance of the integrase inhibitor elvitegravir and of several PIs, eg, atazanavir and darunavir. It is marketed as a pharmacokinetic enhancer of elvitegravir (plus tenofovir-DF/emtricitabine, Stribild), and has been coadministered in a number of studies as a pharmacoenhancer of atazanavir as described above. Being a substrate of CYP3A, cobicistat itself is vulnerable to changes in isoenzyme kinetics if other drugs that are coadministered either increase (eg, azole derivatives and clarithromycin) or decrease (eg, rifabutin, carbamazepine, and phenytoin) its plasma exposure. Cobicistat may even simultaneously increase the plasma exposure of the coadministered drugs, if these are not only inhibitors but also substrates of certain CYPs. A list of all interactions with cobicistat being evaluated prior to approval of Stribild is shown in .Citation64 However, information on many clinically relevant drug interactions is not available as yet and should be obtained, especially if dose adjustments may become necessary in (clinically) unavoidable combinations.

Table 7 Interactions with cobicistat when coadministered with elvitegravir in alphabetic order

Two recent abstracts regarding cobicistat were presented at the 2014 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Boston, MA, USA. One presented the bioequivalence of two pediatric formulations versus the adult tablet. One study arm evaluated the pharmacokinetics of 3×50 mg immediate-release tablets versus the 150 mg adult tablet formulation and showed bioequivalence with regard to peak plasma concentration (geometric mean ratio [GMR] 100, 90% CI 92.8–108) and AUC (GMR 95, 90% CI 88.9–101), and a second arm compared the pharmacokinetics of 7.5×20 mg (tablet divided using a pill cutter) versus the adult 150 mg tablet formulation and again showing bioequivalence within the protocol-defined specifications for peak plasma concentration (GMR 91.9, 90% CI 86.8–97.4) and Acing (GMR 96.6, 90% CI 90.0–104), respectively.

The effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of cobicistat has also been evaluated in a study by Shiomi et al who tested the effects of fasting conditions, a standard breakfast, and a protein-rich drink using a three-way crossover design in healthy volunteers. Administration of a single dose showed decreased plasma concentrations of elvitegravir (50%) and tenofovir (28%) when taken under fasting conditions but no differences between the study groups for emtricitabine and cobicistat.Citation65

Pharmacodynamics

Noninferiority was established for all cobicistat-boosted therapy regimens in the preapproval studies when compared with ritonavir-boosted regimens. Given that cobicistat itself has no antiviral effects, it is redundant to discuss the results of the pivotal studies regarding efficacy. Safety is the important parameter to be discussed in the clinical utility of cobicistat.

However, it is of note that the two Phase IIIb switch studies (STRATEGY-PI and STRATEGY-NNRTI) have shown that patients with maintained suppression of viral load of more than 6 months can switch from a PI-based or NNRTI-based cART to once-daily Stribild as maintenance therapy; both studies showed at least noninferiority of the new cobicistat-containing regimen versus the former cART.Citation59,Citation60 Earlier it was shown that a switch from twice-daily raltegravir-based cART to once-daily Stribild showed comparable safety and efficacy for both regimens.Citation66

Discussion

To appraise the advantages and disadvantages of cobicistat as a pharmacoenhancer of cART one needs to discriminate between pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects, it must be taken into account that long-term data are not yet available and data are scarce regarding special patient groups, ie, children aged <12 years, pregnant women, and elderly patients aged over 65 years.

The CYP3A selectivity of cobicistat metabolism can contribute to better management of drug-drug interactions with cART. The enormous potential of drug-drug interactions involving ritonavir, caused by its coincidental and complex effects on various cytochromes, UGT, and P-glycoprotein, will in all likelihood not be seen with cobicistat and make cART pharmacokinetics much more predictable in future.

However, this will also be to the detriment of the pharmacoenhancing properties of cobicistat. Taking into account that ritonavir-mediated inhibition of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1), especially at the blood–brain barrier, has resulted in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) PI concentrations at least exceeding the minimum inhibitory concentration for wild-type HIV, cobicistat-boosting without P-glycoprotein inhibition may lead to suboptimal PI concentrations in the CSF. For instance, CSF concentrations of ritonavir-boosted darunavirCitation67 and atazanavirCitation68 exceed the IC50 of wild-type HIV only by 20%–100%, and the effect of P-glycoprotein inhibition has not yet been quantified in this metabolic setting. So far, it is not known whether cobicistat is as effective as ritonavir in inhibiting P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux at the blood-brain barrier.Citation69 Currently one study of Scott Letendre is about to start in the U.S.A (www.fda.gov, clinical trials Identifier No. NCT02251236) in order to clarify this question.Citation70 There is certainly a strong demand for pharmacokinetic studies addressing this issue.

One handicap of pharmacoenhancement with ritonavir is the high rate of gastrointestinal side effects, especially chronic diarrhea if combined with PIs which cause low plasma ritonavir concentrations and probably high gut concentrations of not resorbed ritonavir, as shown with lopinavir, amprenavir, and saquinavir.Citation71 HIV PI combinations accounting for high ritonavir plasma concentrations, ie, atazanavir/ritonavir or darunavir/ritonavir, have a much lower prevalence of gastrointestinal side effects. However, the counterpart of ritonavir and, cobicistat, may also cause gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea and vomiting, but causes diarrhea to a much lower extent and most probably due to the pharmacological properties of the antiretrovirally effective combination partners. In the long run, this could considerably increase the quality of life for many patients suffering from chronic diarrhea caused by cART over years on treatment.

In the early Phase II studies, cobicistat revealed an increase of serum creatinine with a subsequently calculated dose-dependent and time-dependent decrease in GFR in study patients.Citation16,Citation72 The focus was put on a possible negative effect on renal function in patients. The detected serum creatinine increases, which reached a plateau after 4 weeks on therapy and remained unchanged until week 48 in the early pivotal trials, affected the Cockcroft-Gault formula-based calculation of estimated GFR, which is used in most clinical settings for kidney diagnostics. However, it could be demonstrated that the real GFRCitation73 was not influenced at all, as shown by stable iohexol clearance. The mechanism behind this effect is a cobicistat concentration-dependent inhibition of the renal transmembrane transporter SLC47A1, which is located at the apical tubular cell membrane and is part of the excretion pathway of creatinine. Indeed, this phenomenon has been already described for other drugs such as cimetidine, trimethoprim, and dolutegravir. A following investigation of the impact on proximal renal tubular transporters could show that cobicistat, ritonavir, cimetidine, and trimethoprim inhibit the SLC47A1 transporter at comparable IC50 values of 1.87, 1.34, 0.95, and 3.31 μM (). However, this does not explain differences between cobicistat and ritonavir as described before. One possible explanation is the different concentrations reached by cobicistat or ritonavir at the proximal tubular membrane compartment.Citation56 The clinical relevance of this phenomenon is not direct but indirect, so clinicians must discriminate between cobicistat-related creatinine elevations and real tubular damage. Creatinine is no more a leading parameter for that and further routine controls must be performed, eg, urinary protein and serum phosphate.

Figure 1 Pathway of renal creatinine transport via efflux transporters SLC22A2 and SLC47A1 over the proximal tubular cell membranes from blood to urine.

After so many years, a strong competitor of ritonavir has entered the stage. Cobicistat is a long expected alternative pharmacoenhancer for cART probably leading to easier handling of combination pharmacotherapy and predictability of drug-drug interactions with cART in many conceivable drug combinations. Cobicistat has not yet revealed a high rate of undesirable or unexpected side effects. However, not having completed its second year on the market, the utility of cobicistat as pharmacoenhancer of cART has to be appraised with caution; in comparison with ritonavir, a much smaller number of patients have been exposed to cobicistat for a comparably short time to date. In particular, the proportion of female volunteers and patients in the preapproval trials does not correspond with the proportion of women infected with HIV-1 worldwide,Citation50 so more studies are required on the long-term safety in women, especially those of childbearing age.

Data on pregnant women, younger children, and patients aged over 65 years are scarce. Although categorized as “B” in the US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy categories due to the drugs preclinical safety profile, real life data during pregnancy as well as studies in special patient groups are in demand to gain more safety in prescription and handling situations, like the inception of pregnancy while being on a cobicistat-containing cART. Cobicistat has been evaluated and was approved as a pharmacoenhancer in only one fixed-drug combination as yet, but is already under evaluation for accessory fixed-dose combinations. However, its timely availability as a single tablet that could be individually combined with other antiretrovirals would be desirable.

Disclosure

The author has received fees for educational lectures from AbbVie, Jannssen Cilag, ViiV Healthcare and GILEAD through the past five years. The author has not received travel expensions or honorariums for any kind of scientific work. The author declares no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LeeLKaronJSelikRNealJFlemingPSurvival after AIDS diagnosis in adolescents and adults during the treatment era, United States, 1984–1997JAMA19982851308131511255385

- MocroftALedergerberBKatlamaCDecline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: an observational studyLancet2003362222912853195

- Collot-TeixeiraSDe LorenzoFWatersLImpact of different low-dose ritonavir regimens on lipids, CD36, and adipophilin expressionClin Pharmacol Ther20098537537819118379

- CarrACardiovascular risk factors in HIV-infected patientsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200334Suppl 1S73S7814562861

- SaxPEKumarPTolerability and safety of HIV protease inhibitors in adultsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2004371111112415319670

- Friis-MollerNReissPSabinCAClass of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med20073561723173517460226

- MorgelloSMahboobRYakoushinaTKhanSHagueKAutopsy findings in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected population over 2 decades: influences of gender, ethnicity, risk factors, and timeArch Pathol Lab Med200212618219011825115

- Friis-MollerNSabinCWeberRCombination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med20033491993200314627784

- PerronneCAntiviral hepatitis and antiretroviral drug interactionsJ Hepatol200644S119S12516360231

- WilbyKJGreanyaEDFordJAYoshidaEMPartoviNA review of drug interactions with boceprevir and telaprevir: implications for HIV and transplant patientsAnn Hepatol20121117918522345334

- VachonMLDieterichDTThe HIV/HCV-coinfected patient and new treatment optionsClin Liver Dis20111558559621867938

- SorianoVShermanKERockstrohJChallenges and opportunities for hepatitis C drug development in HIV-hepatitis C virus-co-infected patientsAIDS2011252197220821866039

- SedenKBackDKhooSNew directly acting antivirals for hepatitis C: potential for interaction with antiretroviralsJ Antimicrob Chemother2010651079108520335191

- HsuAGrannemanGRBertzRJRitonavir. Clinical pharmacokinetics and interactions with other anti-HIV agentsClin Pharmacokinet1998352752919812178

- GallantJEProtease-inhibitor boosting in the treatment-experienced patientAIDS Rev2004622623315700621

- CohenCElionRRuanePRandomized, phase 2 evaluation of two single-tablet regimens elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the initial treatment of HIV infectionAIDS201125F7F1221412057

- ElionRCohenCGatheJPhase 2 study of cobicistat versus ritonavir each with once-daily atazanavir and fixed-dose emtricitabine/tenofovir df in the initial treatment of HIV infectionAIDS2011251881188621811136

- RobertsNMartinJKinchingtonDRational design of peptide-based HIV proteinase inhibitorsScience19902483583612183354

- DannerSCarrALeonardJEuropean-Australian Collaborative Ritonavir Study GroupA short-term study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of ritonavir, an inhibitor of HIV-1 proteaseN Engl J Med1995333152815337477167

- MarkowitzMSaagMPowderlyWGA preliminary study of ritonavir, an inhibitor of HIV-1 protease, to treat HIV-1 infectionN Engl J Med1995333153415397477168

- LorenziPYerlySAbderrakimKToxicity, efficacy, plasma drug concentrations and protease mutations in patients with advanced HIV infection treated with ritonavir plus saquinavir. Swiss HIV Cohort StudyAIDS199711F95F999342060

- MerryCBarryMGMulcahyFSaquinavir pharmacokinetics alone and in combination with ritonavir in HIV-infected patientsAIDS199711F29F339084785

- HoetelmansRMMeenhorstPLMulderJWBurgerDMKoksCHBeijnenJHClinical pharmacology of HIV protease inhibitors: focus on saquinavir, indinavir, and ritonavirPharm World Sci1997191591759297727

- HsuAGrannemanGRCaoGPharmacokinetic interaction between ritonavir and indinavir in healthy volunteersAntimicrob Agents Chemother199842278427919797204

- BuscherAHartmanCKallenMAGiordanoTPImpact of antiretroviral dosing frequency and pill burden on adherence among newly diagnosed, antiretroviral-naive HIV patientsInt J STD AIDS20122335135522648890

- JudayTGuptaSGrimmKWagnerSKimEFactors associated with complete adherence to HIV combination antiretroviral therapyHIV Clin Trials201112717821498150

- KaufTLDavisKLEarnshawSRDavisEASpillover adherence effects of fixed-dose combination HIV therapyPatient Prefer Adherence2012615516422399848

- SterrantinoGSantoroLBartolozziDTrottaMZaccarelliMSelf-reported adherence supports patient preference for the single tablet regimen (STR) in the current cART eraPatient Prefer Adherence2012642743322723727

- BangaloreSKamalakkannanGParkarSMesserliFHFixed-dose combinations improve medication compliance: a meta-analysisAm J Med200712071371917679131

- GermanPWarrenDWestSHuiJKearneyBPPharmacokinetics and bioavailability of an integrase and novel pharmacoenhancer-containing single-tablet fixed-dose combination regimen for the treatment of HIVJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20105532332920683270

- RamanathanSWarrenDWeiLHuiJKearneyBPharmacokinetic boosting of atazanavir with the pharmacoenhancer GS-9350 versus ritonavirPresented at the 49th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapySeptember 12 15 2009San Francisco, CA, USA

- GallantJEKoenigEAndrade-VillanuevaJCobicistat versus ritonavir as a pharmacoenhancer of atazanavir plus emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in treatment-naive HIV type 1-infected patients: week 48 resultsJ Infect Dis2013208323923532097

- MathiasALiuHWarrenDRSekarVJKearneyBPRelative bio-availability and pharmacokinetics of darunavir when boosted with the pharmacoenhancer GS-9350 versus ritonavirPresented at the 11th International Workshop Clinical Pharmacology of HIV TherapyApril 7 9 2010Sorrento, Italy

- KakudaTvan de CasteeleTPetrovicROsomerMTomakaFHoetelmansRBioequivalence of darunavir/cobicistat fixed-dose combination tablet (FDC) versus single agents in healthy volunteersPresented at the 14th International Workshop on Clinical PharmacologyApril 22–24, 2013Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- CooperCvan HeeswijkRGallicanoKCameronDA review of low-dose ritonavir in protease inhibitor combination therapyClin Infect Dis2003361585159212802760

- EaglingVBackDBarryMDifferential inhibition of cytochrome P450 isoforms by the protease inhibitors ritonavir, saquinavir and indinavirBr J Clin Pharmacol1997441901949278209

- HsuAGrannemannGBertzRRitonavir. Clinical pharmacokinetics and interactions with other anti-HIV agentsClin Pharmacokinet1998352752919812178

- HsuAGrannemannGWittGMultiple-dose pharmacokinetics of ritonavir in human immunodefficiency virus-infected subjectsAntimicrob Agents Chemother1997418989059145841

- GranforsMWangJKajosaariLLaitilaJNeuvonenPBackmanJDifferential inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4, 3A5 and 3A7 by five human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitors in vitroBasic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol200698798516433896

- KumarGDykstraJRobertsEPotent inhibition of the cytochrome P-450 3A-mediated human liver microsomal metabolism of a novel HIV protease inhibitor by ritonavir: a positive drug-drug interactionDrug Metab Dispos19992790290810421617

- Kaletra FachinformationAbbott Laboratories LtdBerkshire, UK EU/1/01/172/004 EU/1/01/172/005EU/1/01/172/007 2010,20.03.2010. German

- von HentigNLotschJCytochrome P450 3A inhibition by atazanavir and ritonavir, but not demography or drug formulation, influences saquinavir population pharmacokinetics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected adultsAntimicrob Agents Chemother2009533524352719528289

- CrommentuynKKappelhoffBMulderJPopulation pharmacokinetics of lopinavir in combination with ritonavir in HIV-1-infected patientsBr J Clin Pharmacol20056037838916187970

- SolasCPoizot-MartinIDrogoulMTherapeutic drug monitoring of lopinavir/ritonavir given alone or with a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitorBr J Clin Pharmacol20045743644015025741

- HsuAIsaacsonJBrunSPharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic analysis of lopinavir-ritonavir in combination with efavirenz and two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in extensively pretreated human immunodeficiency virus-infected patientsAntimicrob Agents Chemother20034735035912499212

- GermanPLuiCWarrenDEffect of cobicistat on glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in subjects with normal and impaired renal functionAbstract presented at the 51st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapySeptember 17–20, 2001Chicago, IL, USA

- ElionRGatheJRashbaumBThe single-tablet regimen elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disproxil fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF; “QUAD”) maintains a high rate of virologic suppression and cobicistat (COBI) is an effective pharmacoenhancer through 48 weeksPresented at the 50th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapySeptember 12–15, 2010Chicago, IL, USA

- SaxPDeJesusEMillsAZolopaACohenCWohlDElvite-gravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir (Quad) Has Non-inferior Efficacy and Favorable Safety Compared to Efavirenz/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir in Treatment-naïve HIV-1+ SubjectsConference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections2012Seattle, USA Abstract 101

- WohlDACohenCGallantJEA randomized, double-blind comparison of single-tablet regimen elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF versus single-tablet regimen efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 144 resultsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201465e118e12024256630

- ZolopaASaxPEDeJesusEA randomized double-blind comparison of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 96 resultsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2014639610023392460

- De JesusERockstrohJHenryKMolinaJMGatheJRamanathanSEfficacy and safety of Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/tenofovir DF “Quad” Compared to Ritonavir-boosted Atazanavir plus Emtricitabine/Tenofovir DF in Treatment Naive HIV-1 Infected SubjectsConference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections2012Seattle, USA Poster 627

- United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDSUNAIDS report on the global epidemic of HIV2013 Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdfAccessed October 3, 2014

- ClumeckNMolinaJMHenryKA randomized, double-blind comparison of single-tablet regimen elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricit-abine/tenofovir DF vs ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus emtricitabine/tenofovir DF for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 144 resultsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201465e121e12424346640

- RockstrohJKDeJesusEHenryKA randomized, double-blind comparison of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir DF vs ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus coformulated emtricitabine and tenofovir DF for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: analysis of week 96 resultsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20146248348623337366

- DeJesusERockstrohJKHenryKCo-formulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus co-formulated emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trialLancet20123792429243822748590

- CohenCShamblawDRuanePSingle-tablet, fixed-dose regimen of elvitegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/GS-9350 achieves a high rate of virologic suppression and GS-9350 is an effective boosterPresented at the 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic InfectionsFebruary 16–19, 2010San Francisco, CA, USA

- LepistEIZhangXHaoJContribution of the organic anion transporter OAT2 to the renal active tubular secretion of creatinine and mechanism for serum creatinine elevations caused by cobicistatKidney Int20148635035724646860

- Rodriguez-NovoaSMartin-CarboneroLBarreiroPGenetic factors influencing atazanavir plasma concentrations and the risk of severe hyperbilirubinemiaAIDS200721414617148966

- PozniakAMarkowitzMMillsASwitching to coformulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir versus continuation of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor with emtricitabine and tenofovir in virologically suppressed adults with HIV (STRATEGY-NNRTI): 48 week results of a randomised, open-label, phase 3b non-inferiority trialLancet Infect Dis20141459059924908550

- ArribasJRPialouxGGatheJSimplification to coformulated elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir versus continuation of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor with emtricitabine and tenofovir in adults with virologically suppressed HIV (STRATEGY-PI): 48 week results of a randomised, open-label, phase 3b, non-inferiority trialLancet Infect Dis20141458158924908551

- CustodioJMRheeMShenGLingKHKearneyBPRamanathanSPharmacokinetics and safety of boosted elvitegravir in subjects with hepatic impairmentAntimicrob Agents Chemother2014582564256924550332

- CustodioJGarnerWJinFEvaluation of the drug interaction potential between the pharmacokinetic enhancer cobicistat and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in healthy subjectsPresented at the 14th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV TherapyApril 22–24, 2013Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- European Medicines AgencyZusammenfassung der Merkmale des Arzneimittels Stribild http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/de_DE/document_library/EPAR_(SPc in German)_Product_Information/human/002574/WC500144272.pdfAccessed July 20, 2014

- University of California, San FranciscoAll interactions with elvitegravir/cobicistat2013 Available from: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/insite?page=ar-00-02¶m=225&post=4Accessed October 3, 2014

- ShiomiMMatsukiSIkedaAEffects of a protein-rich drink or a standard meal on the pharmacokinetics of elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine and tenofovir in healthy Japanese male subjects: a randomized, three-way crossover studyJ Clin Pharmacol20145464064824615728

- MillsACrofootGOrtizRSwitching from twice-daily raltegravir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine to once-daily elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in virologically suppressed, HIV-1-infected subjects: 48 weeks dataHIV Clin Trials201415515624710918

- CapparelliEVHollandDOkamotoCLopinavir concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid exceed the 50% inhibitory concentration for HIVAIDS20051994995215905676

- BestBMLetendreSLBrigidELow atazanavir concentrations in cerebrospinal fluidAIDS200923838719050389

- LetendreSCentral nervous system complications in HIV disease: HIV-associated neurocognitive disorderTop Antivir Med20121913714222156215

- LepistEIPhanTKRoyACobicistat boosts the intestinal absorption of transport substrates, including HIV protease inhibitors and GS-7340, in vitroAntimicrob Agents Chemother2012565409541322850510

- European Medicines Agency 2009, Dok.-Ref.: EMA/793683/2009 EMEA/H/C/127:Last update 01/2010, Accessed 2025.2003.2012

- MathiasAAGermanPMurrayBPPharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of GS-9350: a novel pharmacokinetic enhancer without anti-HIV activityClin Pharmacol Ther20128732232920043009

- MathiasAAGermanPMurrayBPPharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of GS-9350: a novel pharmacokinetic enhancer without anti-HIV activityClin Pharmacol Ther20108732232920043009

- Stribild Package InsertFoster City, CA, USAGilead Sciences, Inc2012 Available from: http://www.gilead.com/∼/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/hiv/stribild/stribild_pi.pdfAccessed October 3, 2014

- Department of Health and Human ServicesGuidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in pediatric HIV infection2122013 Available from: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/pedi-atricguidelines.pdfAccessed February 2, 2015

- BruceRDWinklePCustodioJPharmacokinetics of cobicistat-boosted elvitegravir administered in combination with methadone or buprenorphine/naloxonePresented at the 52nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapySeptember 9–12, 2012San Francisco, CA, USA

- BruceRDWinklePCustodioJMThe pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between buprenorphine/naloxone and elvitegravir/cobicistat in subjects receiving chronic buprenorphine/ naloxone treatmentJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20146348048423599011

- RamanathanSWangHSzwarcbergJKearneyBPSafety/tolerability, pharmacokinetics and boosting of twice-daily cobicistat administered alone or in combination with darunavir or tipranavirPresented at the13th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV TherapyApril 16–18, 2012Barcelona, Spain

- Gilead Sciences LtdSPC for Tybost 150mg film coated tablet Available from: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/28298Accessed July 20, 2014

- BruceRDWinklePCustodioJMInvestigation of the interactions between methadone and elvitegravir-cobicistat in subjects receiving chronic methadone maintenanceAntimicrob Agents Chemother2014576154615724080665

- CustodioJMWangHHaoJPharmacokinetics of cobicistat boosted-elvitegravir administered in combination with rosuvastatinJ Clin Pharmacol20145464965624375014

- CustodioJGuoSLawsonELack of clinically relevant drug interactions between elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and telaprevir 2013Poster presented at the 53rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and ChemotherapySeptember 10–13Denver, CO, USA

- University of California San FranciscoAll interactions with elvitegravir/cobicistat 2013 Available from: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/insite?page=ar-00-02¶m=225&post=4Accessed June 20, 2014