Abstract

Medical advances continue to change the face of human immunodeficiency virus– acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). As life expectancy increases, the number of people living with HIV rises, presenting new challenges for the management of a chronic condition. Aging, nutrition, and physical activity can influence outcomes in other chronic conditions, and emerging data show that each of these factors can impact viral replication and the immune system in HIV. HIV infection results in a decline of the immune system through the depletion of CD4+ T cells. From initial infection, viral replication is a continuous phenomenon. Immunosenescence, a hallmark of aging, results in an increased susceptibility to infections secondary to a delayed immune response, and this phenomenon may be increased in HIV-infected patients. Optimal nutrition is an important adjunct in the clinical care of patients with HIV. Nutritional interventions may improve the quality and span of life and symptom management, support the effectiveness of medications, and improve the patient’s resistance to infections and other disease complications by altering immunity. Moderate physical activity can improve many immune parameters, reduce the risk of acute infection, and combat metabolic abnormalities. As people with HIV age, alternative therapies such as nutrition and physical activity may complement medical management.

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is no longer a disease of the young. It has been suggested that by 2015, 50% of those living with HIV in the United States will be 50 years of age and older.Citation1 Similar trends have been appreciated in other developed nations.Citation2,Citation3 Reports for underdeveloped nations are limited, but recent data suggest the HIV-infected population over the age of 50 is increasing in some African countries.Citation4,Citation5 Advances in antiretroviral (ARV) therapy have improved morbidity and increased longevity for both children and adults. Optimal medical management and enhanced laboratory monitoring for the effectiveness of treatment is also, in part, responsible for longer life expectancy. The face of HIV continues to evolve, and the disease is now considered a chronic condition. For people infected with HIV, more deaths are attributed to non-HIV related causes,Citation6 including cardiovascular disease.

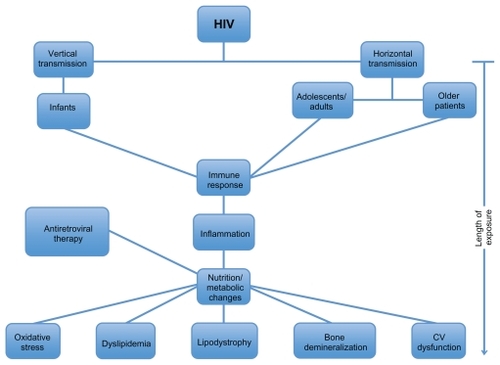

Acquisition of HIV can occur during the entire age spectrum from perinatal transmissionCitation7 to disease acquired through risky behaviors in adolescence and adulthood.Citation8 Older individuals are generally not believed to be at as much risk for HIV; however, it has become evident that the incidence of HIV in this population is increasing.Citation1–Citation5 The acute infection with HIV begins a cascade of nutritional and cardiometabolic events that are similar for many patients (). Since the cascade of events may occur across all age groups, many of the treatment goals are similar for all HIV-infected patients – to optimize immune function and to achieve the greatest degree of viral suppression while decreasing morbidity and mortality from secondary illness.Citation9

Figure 1 Nutritional and cardiometabolic events with HIV infection.

From the initial infection, viral replication is a continuous phenomenon. This process is evident even during the use of highly active ARV therapy (HAART).Citation10 HIV disorders the immune system primarily through depletion of CD4+ T cells that are fundamental in the development of specific immune responses toward infectious agents. The immune system changes with age. “Normal” immune dysfunction is typically found at either end of the age spectrum – both infants and older people are at particular risk. This relative immunodeficient state is further compromised in HIV- infected infants, young children, and older individuals. The older population, most commonly described as anyone with HIV over the age of 50, faces many challenges due to normal changes in the immune system. Aging is associated with immunosenescence that implies the increased susceptibility to infections secondary to a delayed immune response. In addition, older patients have a greater number of comorbidities that may further complicate their health. Thus, age, often, is an independent factor that is associated with impaired immunologic responses.

ARVs have significantly improved morbidity and mortality. Citation11 Nutritional abnormalities, including both malnutrition and obesity, are highly prevalent among HIV-infected children and adults and can independently contribute to declines in health and increases in mortality. Weight loss, cachexia, obesity, and cardiometabolic problems are a few of the nutritional factors that increase the risk of death.

Over the past decades, there have been multiple epidemiological studies showing the relationship between physical activity and overall health in non-HIV populations. Physically active adults are less susceptible to viral and bacterial infections when compared with sedentary adults, suggesting that physical activity improves overall immune function. Research evidence supports the findings that exercise decreases age-associated immunosenescence,Citation12 increases innate immune function,Citation13 and decreases chronic inflammation.Citation14 Physical activity may be important to decrease the effects of some comorbidities such as lipodystrophy by increasing muscle mass, decreasing obesity by decreasing overall adipose tissue, and improving immune function by increasing T cells.

This review will investigate how aging, nutrition, and exercise influence clinical and immunological outcomes in HIV infection.

Aging and HIV infection: immunological inferences

The process of aging produces a functional, biological, and psychological decline in an individual. These changes in total increase the overall risk of disease in older individuals. With aging, the body has a decreased ability to respond to stress, therefore, making a person prone to illness.Citation15 The functional capabilities of the immune system decline with aging, and its decrease in capacity may lead to an increased susceptibility to infectious diseases and cancers.Citation16 Diminution of immune function with age is associated with a decline in the production of growth hormone, estrogen, dehydroepiandrosterone, and melatonin.Citation17 The changes in hormone levels are also associated with age-related degenerative diseases.Citation18 It has been postulated that T and B cells play a critical role in the development of disorders more commonly seen with older age.Citation19

The immune system encompasses innate, humoral, and cellular immunity. The newborn immune system is immature and leads to an increased susceptibility to both viral and bacterial pathogens.Citation20 The humoral immune system is underdeveloped in neonates with large dependence on maternally acquired antibodies.Citation20 With age, there is a decrease in the functional ability of the natural killer (NK) cellsCitation21 despite a compensatory increase in the absolute number of NK cells.Citation22 Reports have also shown decreases in the number of macrophages and granulocytes,Citation23 cells that are important defense against microbes. Finally, proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 are increased with aging and have been associated with morbidity and mortality.Citation24,Citation25 Increased levels of immunoglobulins A and G with decreased numbers of B lymphocytesCitation26 are most significant among the changes in humoral immunity with aging. The reduced responsiveness and altered antibody-mediated defense mechanisms of the humoral immune system associated with senescence lead to an increased risk of disease. Cellular immunity is also affected with aging. Significant decreases are appreciated in CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells and naïve T lymphocytes.Citation27 These changes point to the decline in immunization response and are predictive of mortality.Citation28

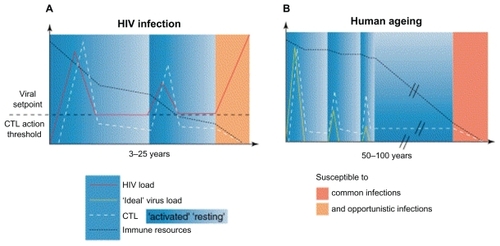

With advanced age, many diseases can mimic HIV, therefore, making the diagnosis at times delayed. The majority of older patients are diagnosed with HIV only when they become symptomatic, and the disease has progressed considerably. Citation29 There is evidence of accelerated immunosenescence in HIV-infected individuals as they age. The replicative capabilities of the cells of the immune system over a lifetime are limited, even under normal circumstances.Citation30 shows the parallels between immunosenescence with normal aging and that with HIV.Citation31 Chronic immune activation contributes to the early aging of the immune system in uninfected people. In HIV infection, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells express CD57, a senescence marker, soon after the patient is infected with HIV.Citation32 Specific HIV-activated T-cell clones may prematurely reach replicative senescence with loss of CD8+ T-cell populations that typically control viral replication. Thus, the normal process of immunosenescence is likely accelerated in HIV.

Figure 2 Schematic representation of immunosenescence with normal aging and that with HIV. Copyright © 2002 Elsevier. Reprinted with permission from Appay V, Rowland-Jones SL. Premature ageing of the immune system: the cause of AIDS? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:580–585.Citation31

The impaired renewal of T-cell populations can be caused by a number of factors in HIV infection. The thymus, which typically generates new populations of naïve T cells, undergoes involution and atrophy in HIV-infected individuals.Citation33 Furthermore, there may also be a dysregulation of hematopoiesis where there are a lower absolute number of progenitor cells with decreased ability to generate new cells.Citation34,Citation35 Overall, the acceleration of immunosenescence in the HIV-infected individual may ultimately place the patient at higher risk of developing disorders associated with further impairment of the immune system (infections, cancers).

Clinically, during the pre-ARV therapy era, studies showed that HIV-infected patients of age 14–24 were anticipated to live 12.5 years on average, whereas those of age 45–54 were expected to live only 7.9 years on average.Citation36 In addition, another study determined that the rate of CD4+ cell decline was significantly greater in the older group (over 40 years of age) when compared with the younger group (16–20 years of age).Citation37 There is an approximate inverse relationship between CD4+ cell count and survival time in most HIV cases.Citation38 The increased rate of CD4+ decline in the older groups may in turn be associated with faster disease progression, and as CD4+ levels reach critical values, viral loads may increase.

The benefits of ARVs in reducing morbidity and mortality for patients with HIV–acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) must be balanced against their potential side effects and toxicities. The ideal ARV is one that combines efficacy, adherence, tolerability, yet minimizes viral resistance.Citation39 The use of combination ARV therapy typically in the form of HAART can often achieve these goals. Careful follow-up care is important to prevent potential adverse events and toxicity. Citation40 More concerning is the fact that although guidelines for HAART are described for children, adolescents, and adults,Citation41 there are no specific guidelines for the older patients with HIV despite the fact that this group is growing.

Older individuals with CD4+ levels below 500 cells/uL are associated with a death rate two times higher than those with a CD4+ of 650 cells/μL and above.Citation42 The older population may be at a disadvantage in maintaining higher CD4+ levels as they have diminished ability to stimulate CD4+ cells as a response to ARVs. A study by Goetz et alCitation43 suggested that HIV-infected patients of 55 years and older demonstrated significantly lower CD4+ cell reconstitution when compared with the younger cohort. It has also been noted that persons with reduced immune system function, as found among older individuals, demonstrate a slower response to the effects of HAART.Citation44 Therefore, older adults with long-term or new HIV infection can be challenging to manage clinically because of their altered responses to HIV and ARV therapy, owing to decreased immune function that comes naturally with aging but is likely exacerbated by HIV.

Nutrition, HIV, and immune response

Dietary therapy is an important adjunct in the clinical care of patients infected with HIV. In many conditions, achieving and maintaining optimal nutrition can improve an individual’s immune function, reduce the incidence of complications associated with HIV infection, attenuate the progression of HIV infection, improve quality of life, and ultimately reduce mortality associated with HIV.Citation45 Multiple strategies to improve nutritional outcomes exist, including ARVs, treatment of coinfections, nutritional counseling, pharmacologic agents to stimulate appetite or anabolism, and nutritional supplements. This section discusses the effects of nutrition therapy on immunologic status and how nutrition may alter the natural course of HIV.

Nutritional complications remain a challenging issue for HIV-infected children and adults in the HAART era and can often contribute to both morbidity and mortality of those infected with HIV. Weight loss, lean tissue depletion, lipoatrophy, anorexia, nutrient malabsorption, diarrhea-induced nutrient losses, and a hypermetabolic state increase risk of death.Citation46 In addition, several non-AIDS-related problems such as serum lipid abnormalities, insulin resistance, osteopenia, and increased risk for cardiovascular diseases have emerged since the introduction of HAART.

Several HIV-specific medications, particularly nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, may inhibit replication of mitochondrial DNA and cause vomiting and diarrhea that may result in the loss of micronutrients. Mitochondrial toxicity may also increase the production of reactive oxygen species, which cause oxidative damage, leading to lactic acidosis. Mitochondrial dysfunction may be responsible for HAART-associated lipodystrophy.Citation47 Protease inhibitor therapy has been linked to lipid abnormalitiesCitation48 and changes in cardiovascular risk profilesCitation49,Citation50 with decreased brachial artery reactivityCitation51 and greater carotid intima media thickness. Citation52 Although non-nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors are not associated with as many adverse cardiovascular risks, they have their own set of toxicities in other systems.Citation53 Patients beginning combination therapy, or HAART, often experience a gain in central adiposity and lean mass over the first 6 months and may develop glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and peripheral lipoatrophy and decrease in lean mass after 6 months.Citation54

Patients who have nutritional and metabolic disturbances that result in weight loss and wasting may show a chronic inflammatory state. Inflammation and other immune responses alter nutritional status through sequestration of minerals (eg, iron and zinc), impaired absorption, increased nutrient loss, or altered nutrient utilization.Citation55

Micronutrients are essential for maintaining proper immunologic function. Cellular mechanisms by which trace elements and other nutrients can influence immunity include nutrient effects on protein synthesis, cytokine production, mitosis, apoptosis, and signal transduction.Citation56 Micronutrient deficiencies, as a result of acute or chronic inflammation, can persist in the HAART era. Studies suggest low serum levels of retinol, α-tocopherol, selenium, and zinc accelerate the progression of HIV to AIDS and death.Citation57,Citation58 In certain clinical situations of stress, the production of free radicals is greater than their normal clearance. At that point, the host’s endogenous antioxidant system plays a major role to prevent or limit the deleterious effects of free radicals and, in patients with HIV, maintain immune function.Citation58–Citation60 Endogenous antioxidants include enzymatic antioxidants (eg, zinc in superoxide dismutase or selenium in glutathione peroxidase), free radical scavengers (eg, vitamins A, C, or E), and metal chelators.Citation61 Sources of antioxidants include the diet or the use of specific nutritional supplements. Increased free radical formation and reduced antioxidant defenses can result from a combination of insufficient dietary intake and excessive utilization of specific antioxidants without adequate recycling or replacement. Recognizing and correcting multiple vitamin marginal deficiencies may be the key to the treatment of many HIV-infected patients.

Nutritional status influences the immune system at different levels. Subclinical or frank deficiencies of micronutrients reduce circulating amounts and functional capacities of key immune cells and proteins, including innate immunity and components of adaptive immunity such as T- and B-lymphocyte functions. Other micronutrient deficiencies, including that of essential fatty acids, folate, zinc, and vitamin A, may lead to mucosal lesions or reduced mucosal integrity, thus increasing the risk of infections.Citation62

Essential trace elements (Cu, Fe, Se, and Zn) can influence immunity due to their presence in metalloenzymes that have key immunologic functions. For instance, zinc is essential for the development of immunity during childhood because of its global role in the normal development and function of cell-mediating innate immunity, neutrophils, NK cells, and macrophages. Among vitamins, vitamin A deficiency reduces lymphocyte response, vitamin C deficiency depresses cell-mediated immune response, and vitamin E deficiency impairs T cell-mediated function and lymphocyte proliferation. Deficiency of any single nutrient may impair resistance to infection, and conversely, infections, even if mild, may result in adverse effect on nutritional status.Citation63

The keystones of mounting an effective immune response are rapid cellular proliferation and early synthesis of regulatory and/or protective proteins. Deficiencies of essential nutrients are potentially one of the rate-limiting factors in the development and maintenance of immune responses. A summary of the effects of nutrition interventions on the immune function of HIV-infected patients is described in .

Table 1 Summary of the effects of nutrition interventions on the immune function of HIV-infected patients

Macronutrients interventions

Adequate intake of micronutrients and macronutrients is essential for the restoration and maintenance of body cell mass and normal function, including immunity. The benefits of providing adequate amounts of energy and protein for people living with HIV are clear.Citation73

The evidence of the effects of macronutrient interventions in reducing viral load and morbidity and mortality in children and adults living with HIV is sparse. Studies using supplemental formulas, such as those with hydrolyzed or elemental protein and special protein formulas with whey, glutamine, arginine, or high protein content;Citation70 lipids including fish oil or n-3 fatty acids;Citation74 and fiber interventions,Citation75 suggest that macronutrient supplementation may increase energy intake but do not reliably result in increases in fat-free mass, body cell mass, or immunological parameters such as CD4+ count. A cross-sectional study of men with advanced, asymptomatic HIV demonstrated a positive association between protein intake and body cell mass independent of muscle-building activity.Citation76 Clark et alCitation70 demonstrated that supplementation with specific nutritional supplements, including an amino acid mixture of arginine, glutamine, and β-hydroxy- β-methylbutyrate, significantly increased body weight and decreased viral load but did not alter energy intake, protein intake, fat mass, or CD4+ count. Although studies have shown the potential benefits of n-3 fatty acids on immune function for people with HIV, the recommended intake is currently the same as for the general population.Citation77,Citation78

Micronutrients interventions

Micronutrient supplements may provide cellular and clinical benefits for HIV-infected patients on HAART. Growing evidence supports the importance of essential trace elements – particularly copper, iron, selenium, and zinc – for maintaining immune functions.Citation68,Citation69,Citation79 However, micronutrient supplementation has shown mixed beneficial effects on immunologic status.Citation80,Citation81

A comprehensive review of randomized trials showed that there was no conclusive evidence that micronutrient supplementation (including vitamins A, C, and E, selenium, zinc) effectively reduced morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected children, adults, and pregnant and lactating women.Citation82

Other studies provide additional support for micronutrient supplementation in HIV. Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent in HIV-infected individualsCitation83 and is an emerging nutrient that can positively affect immune function, among other important roles. In one study of over 800 women in Tanzania, women with the highest levels of vitamin D had decreased all-cause mortality, HIV disease progression, and anemia.Citation84 These effects may, in part, be due to the role of vitamin D in immune regulation. Vitamin D receptors have been found on peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and this suggests vitamin D can be an immune modulator.Citation64 Vitamin D has also been shown to have an integral role in innate immunity and response to infections such as tuberculosis.Citation65

Other investigators have demonstrated that antioxidant supplementation improved some measures of oxidative defense in HIV+ adults on HAART.Citation66,Citation67 In another review of randomized clinical trials, Allen et alCitation81 concluded that there is some evidence that supplementation with multiple micronutrients reduces mortality and possibly morbidity, among adults with HIV/AIDS not on HAART. Additional studies are still needed to investigate the effects of multiple micronutrients as an adjunct therapy for people receiving HAART.

Micronutrient supplements may not always prove to be beneficial in HIV-infected individuals. Supplementation with trace elements as single nutrients may lead to micronutrient imbalances, especially in populations with multiple underlying deficiencies.Citation85 Both iron deficiency and excess iron may inhibit some immune functions.Citation79 Likewise with zinc, both deficiency and excessive intake are correlated with reduced CD4 cell counts and survival of the patient with HIV.Citation86 High doses of zinc supplementation may lead to zinc-induced copper deficiencyCitation87 that may further compromise the immune system. Micronutrient supplementation has also been associated with HIV transmission. Randomized trials have shown that maternal vitamin A supplements increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIVCitation88 and can increase mortality in some children born to HIV+ mothers.Citation89

There is growing evidence that routine ingestion of a multivitamin or mineral supplement that includes moderate quantities of essential trace elements may result in improvements in immune functions in older people.Citation85 However, legitimate use of dietary supplementation is to restore a deficiency. Currently, no conclusive evidence supports the use of dietary supplement solely on the basis of improving infectious outcomes in well-nourished HIV-infected individuals. The World Health Organization promotes and supports adequate dietary intake of micronutrients at Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) levels.Citation90 It suggests that patients are likely to benefit from consuming a varied diet that is rich in micronutrients. It is likely that HIV-infected patients, particularly those with poor diets or who live in poverty, may benefit from regular consumption of a multivitamin, mineral, and trace element supplement that contains micronutrients at DRI levels.

Good nutrition and nutrition interventions may help improve the quality and length of life, improve symptom management, support the effectiveness of medications and other therapies, and improve the HIV-infected patient’s resistance to infections and other disease complications.Citation73

Physical activity and immune function

Over the past few decades, epidemiological studies have demonstrated the relationship between physical activity and overall health.Citation91 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that all ages can benefit from moderate amounts of daily activity.Citation87 Physical activity has been shown to assist in weight management, lean muscle development, and body fat reduction.Citation92 However, in individuals with chronic illness, it is important to determine the effectiveness and safety of physical activity to ensure the benefits outweigh the risks.

Physically active adults are less susceptible to viral and bacterial infections when compared with sedentary adults, suggesting that physical activity improves overall immune function. Scientific evidence suggests that exercise delays age-associated immunosenescence,Citation12 increases innate immune function,Citation13 and decreases chronic inflammation.Citation14 Improved immune function plays a critical role in regulating the inflammatory process, a primary contributor to chronic disease.Citation93 Because T-lymphocyte function declines with age, preserving this function with interventions known to improve immunity, such as physical activity, is considered important.Citation13 For example, one study in an older population reported that 6 months of aerobic and resistance training at moderate intensity showed significantly increased CD28+ and CD4+ cells, causing an upregulation of the T-helper cells and decreasing the risk of infection.Citation94

In addition, physical activity can effectively reduce both acute and chronic inflammation.Citation12 A reduction in the chronic inflammatory process, as shown in , may inhibit metabolic disturbances and the risk for concomitant diseases. Physical activity can also stimulate the production of hormones. Starkie et alCitation95 demonstrated that the levels of the stress hormones such as glucocorticoids and epinephrine increase with bouts of exercise. The release of these hormones leads to an acute decrease of inflammation. Thus, in addition to the beneficial effect of lowering levels of inflammatory markers, there is evidence that physical activity stimulates production of anti-inflammatory factors as well.Citation96

HIV infection dramatically changes the physical well-being of an individual, yet the current treatments make it possible for this population to live longer and with greater quality years of life. With this increase in longevity, other chronic conditions are emerging that relate to both normal aging and complications of medical treatments and chronic viral infection. As previously reviewed, individuals with HIV are becoming more susceptible to conditions such as insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease.Citation97 Up to 60% of HIV-infected patients receiving HAART have body composition and metabolic abnormalities.Citation98 HIV-infected patients, including children,Citation99,Citation100 have demonstrated positive health and fitness parameters when participating in structured physical activity interventions, including improved overall quality of life. The effects of physical activity on HIV-infected individuals include physical improvements in body composition with decreased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio and increased lean body mass, and cardiometabolic fitness – all risk factors for cardiovascular disease.Citation99–Citation102

Similar to the general population, HIV-infected patients are at risk for obesity.Citation103 Amorosa et alCitation104 report a higher prevalence in overweight and obesity compared with wasting that was most prevalent in the pre-HAART era. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome among HIV patients is reported between 14% and 18% depending on the definition of the diagnosis.Citation105 As a result, healthcare professionals suggest exercise as a management strategy to improve lean body mass and cardiovascular fitness and decrease metabolic complications of HIV. Obesity alone can negatively impact immune function. A recent report demonstrated that obese patients had lower levels of CD4 cell countsCitation106 and may be associated with slower immunological recovery. Others have shown that obese individuals have higher inflammatory biomarkers and adipokines that may negatively impact the overall function of the immune system.Citation107–Citation109 Taken collectively, obese HIV-infected individual may be at a higher risk of immune dysfunction compared with normally nourished patients. Interventions, such as physical activity, that can impact obesity may be beneficial in improving immune function.

Regular physical activity can positively affect the HIV-infected individual psychologically, and emotional wellness has been linked directly related to immune health. Studies have reported a 22%–45% prevalence of depression among HIV-infected people.Citation110 This high prevalence indicates that depression is a disease that needs to be assessed in all patients with HIV. Depression has been linked to altering the course of infection due to immune function impairment. HIV-infected patients who participate in regular physical activity have higher life satisfaction scores when compared with those who are sedentary.Citation111

The immunological benefits of physical activity, specific to those with HIV infection, include the effects on CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and HIV viral load. Participants in one study, who participated in aerobic physical activity, showed enhanced production of natural antibodies that, in turn, can potentially delay disease progression. These results suggest that physical activity can positively affect immunological factors that usually cause disease progression in HIV.Citation112 Broadbent and GassCitation113 found that 52 weeks of physical activity increases CD4+ and CD25+ percentages in older men. Another study reported an inverse relationship between regular physical activity and viral load,Citation114 a finding that had not been previously supported in the literature. However, most reports indicate that exercise does not positively or negatively impact CD4 count or viral load.Citation99,Citation102,Citation115 The inconsistency of these results emphasize the need for additional studies that control for the amount and intensity of the physical activity intervention, as well as the stage and progression of the disease. Overall, existing literature indicates exercise interventions are physically and immunologically safe in both children and adults with HIV.

As the evidence for the benefits of physical activity on immune and metabolic functions in persons with HIV grows, recommendations for regular exercise should become an integral part of their care across all ages.

Conclusion

HIV-infected children and adults are now expected to live longer, but at the same time, they are at risk for developing health complications as a consequence of a life with chronic viral infection, exposures to medications that carry their own toxicities and side effects, and the natural effects of aging on the immune system. Age-related immunosenescence can increase the challenges of controlling viral loads and optimizing CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell counts. Because immunosenescence is an inherent phenomenon that may be accelerated by HIV, strategies that can potentially modify this process should be used. Nutrition therapy may support the effectiveness of the medical treatments by improving cellular function through the supplementation of both macronutrients and micronutrients. Physical activity, known to provide a number of benefits for noninfected individuals, can exert positive effects on metabolic and cardiovascular functions while not imposing deleterious effects on the immune system. Continued research is needed to further define the effects of optimal nutrition and physical activity on the immune system as HIV-infected individuals grow older.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- EffrosRBFletcherCVGeboKAging and infectious diseases: workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directionsClin Infect Dis20084754255318627268

- OrchiNBalzanoRScognamiglioPAgeing with HIV: newly diagnosed older adults in ItalyAIDS Care20082041942518449818

- PittsMGriersonJMissonSGrowing older with HIV: a study of health, social and economic circumstances for people living with HIV in Australia over the age of 50 yearsAIDS Patient Care STDS20051946046516053403

- National AIDS and STD Control Program MoHKKenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2007: Preliminary ReportNairobi, KenyaMinistry of Health2008

- ShisanaORehleTSimbayiLCParkerWZumaKBhanaASouth African National HIV Prevalence, HIV Incidence, Behaviour and Communication SurveyCape Town, South AfricaHSRC Press2005

- BradyMTOleskeJMWilliamsPLfor Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group219/219C TeamDeclines in mortality rates and changes in causes of death in HIV-1-infected children during the HAART eraJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201053869420035164

- VolminkJSiegfriedNLvan der MerweLBrocklehurstPAntiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infectionCochrane Database Syst Rev20071CD00351017253490

- Center for Disease Control and PreventionHIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: Cases of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2007Atlanta, GeorgiaCDC2007

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and AdolescentsGuidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescentsDepartment of Health and Human Services20091211161 Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdfAccessed May 7, 2010

- BuzónMJMassanellaMLlibreJMHIV-1 replication and immune dynamics are affected by raltegravir intensification of HAART-suppressed subjectsNat Med20101646046520228817

- SterneJAHermanMALedergerberBLong-term effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy in preventing AIDS and death: a prospective cohort studyLancet200536637838416054937

- WoodsJAVieiraVJKeylockKTExercise, Inflammation, and Innate ImmunityImmunol Allergy Clin North Am20092938139319389588

- KohutMLSenchinaDSReversing age-associated immunosenescence via exerciseExerc Immunol Rev20041064115633584

- BruunsgaardHPhysical activity and modulation of systemic low-level inflammationJ Leukoc Biol20057881983516033812

- WeinertBTTimirasPSTheories of AgingJ Appl Physiol2003951706171612970376

- SrinivasanVMaestroniGJMCardinaliDPMelatonin, immune function and agingImmunity and Aging2005217

- SrinivasanVMelatonin, oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseasesAging Cell200239668679

- ArltWHewisonMHormones and immune function: implications of agingAging Cell2004320921615268754

- HakimFTFlomerfeltFABoyiadzisMGressREAging, Immunity and cancerCurr Opin Immunol20041615115615023406

- JaspanHBLawnSDSafritJTBekkerLGThe maturing immune system: implications for development and testing HIV-1 vaccines for children and adolescentsAIDS20062048349416470112

- GinaldiLde MartinisMD’OstilioAThe immune system in the elderly: III. innate immunityImmunol Res19992011712610580637

- BorregoFAlonsoMCGalianiMDNK phenotypic markers and IL2 response on NK cells from elderly peopleExp Gerentol199934253265

- MarianiEMeneghettiANeriSChemokine production by natural killer cells from nonageneriansEur J Immunol2002321524152912115634

- StraubRHMillerLEScholmericJZietzBCytokines and hormones as possible links between endocrinosenescence and immunosenescenceJ Neuroimmunol2000109101510969175

- ForseyRJThompsonJMErnerudhJPlasma cytokines profiles in elderly humansMech Ageing Dev200312448749312714257

- GinaldiLLoretoMFCorsiMPImmunosenescence and infectious diseasesMicrobes Infect2001385185711580980

- PawelecGWagnerWAdibzadehMEngelAT cell immunosenescence in vitro and in vivoExp Gerontol19993441942910433396

- OlssonJWikbyAJohanssonBLöfgrenSNilssonBOFergusonFGAge-related change in peripheral blood T-lymphocyte subpopulations and cytomegalovirus infection in the very old: the Swedish longitudinal OCTO immune studyMech Ageing Dev200012118720111164473

- WooleryWAOccult HIV infection: diagnosis and treatment of older patientsGeriatrics19975251619371104

- AppayVAlmeidaJRSauceDAutranBPapagnoLAccelerated immune senescence and HIV-1 infectionExp Gerentol200742432437

- AppayVRowland-JonesSLPremature ageing of the immune system: the cause of AIDS?Trends Immunol20022358058512464569

- EffrosRBReplicative senescence of CD8 T cells: effect on human ageingExp Gerontol20043951752415050285

- KalayjianRCLandayAPollardRBAge-related immune dysfunction in health and in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease: association of age and HIV infection with naive CD8+ cell depletion, reduced expression of CD28 on CD8+ cells, and reduced thymic volumesJ Infect Dis20031871924193312792869

- MarandinAKatzAOksenhendlerELoss of primitive hematopoietic progenitors in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infectionBlood199688456845788977248

- MosesANelsonJBagbyGCJrThe influence of human immunodeficiency virus-1 on hematopoiesisBlood199891147914959473211

- Collaborative Group on AIDS Incubation and HIV SurvivalTime from HIV-1 seroconversion to AIDS and death before widespread use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative re-analysis. Collaborative Group on AIDS Incubation and HIV Survival including the CASCADE EU Concerted Action. Concerted Action on SeroConversion to AIDS and Death in EuropeLancet20003551131113710791375

- CASCADE CollaborationDifferences in CD4 cell counts at sero-conversion and decline among 5739 HIV-1-infected individuals with well-estimated dates of seroconversionJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200334768314501798

- ThiebautRPellegrinICheneGImmunological markers after long-term treatment interruption in chronically HIV-1 infected patients with CD4 cell count above 400 x 10 (6) cells/lAIDS200519536115627033

- ManfrediRHIV Disease and Advanced Age: An Increasing Therapeutic ChallengeDrugs Aging20021964766912381235

- CarpenterCCJCooperDAFischlMAAntiretroviral therapy in adults: updated recommendations of the International AIDS Society- USA PanelJAMA200028338139010647802

- Working Group on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-infected Children convened by the National Pediatric and Family HIV Resource Center (NPHRC), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the National Institute of Health (NIH)Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in Pediatric HIV infectionMMWR2000159

- PhillipsANNeatonJLundgrenJDThe role of HIV in serious disease other than AIDSAIDS2008222409241819005264

- GoetzMBBoscardinWJWileyDDecreased recovery of CD4 lymphocytes in older HIV-infected patients beginning highly active antiretroviral therapyAIDS2001151576157911504992

- HaynesBFHaleLPWeinholdKJAnalysis of the adult thymus in reconstruction of T lymphocytes in HIV-1 infectionJ Clin Invest199910345345610021452

- MahlunguluSGroblerLAVisserMEVolminkJNutritional interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIVCochrane Database Syst Rev20073CD00453617636766

- American Dietetic AssociationPosition of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: nutrition intervention in the care of persons with human immunodeficiency virus infectionJ Am Diet Assoc20041041425144115354161

- JohnMMooreCBJamesIRChronic hyperlactatemia in HIV-infected patients taking antiretroviral therapyAIDS20011571772311371686

- CarrASamarasKChisholmDJCooperDAPathogenesis of HIV-1 protease inhibitor-associated peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistanceLancet1998351188118839652687

- MonforteAAbramsDPradierCfor Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D:A:D) Study GroupHIV-induced immunodeficiency and mortality from AIDS-defining and non-AIDS-defining malignanciesAIDS2008222143215318832878

- FisherSDMillerTLLipshultzSEImpact of HIV and highly active antiretroviral therapy on leukocyte adhesion molecules, arterial inflammation, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosisAtherosclerosis200618511116297390

- HurwitzBEKlimasNGLlabreMMHIV, metabolic syndrome X, inflammation, oxidative stress, coronary heart disease risk: role of protease inhibitor exposureCardiovasc Toxicol2004430331615470277

- MaggiPSerioGEpifaniGPremature lesions of the carotid vessels in HIV-1-infected patients treated with protease inhibitorsAIDS200014F123F12811101050

- RiveroAMiraJAPinedaJALiver toxicity induced by non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitorsJ Antimicrob Chemother20075934234617255142

- CarrASamarasKBurtonSA syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease inhibitorsAIDS199812F51F529619798

- SembaRDTangAMMicronutrients and the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infectionBr J Nutr199981181189 Review10434844

- ShermanARImmune dysfunction in iron, copper, and zinc deficienciesBodgenJDKlevayLMClinical Nutrition of the Essential Trace Elements and MineralsTotowa, NJHumana Press2000309351

- TangAMGrahamNMSembaRDSaahAJAssociation between serum vitamin A and E levels and HIV-1 disease progressionAIDS1997116136209108943

- JonesCYTangAMForresterJEMicronutrient levels and HIV disease status in HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy in the Nutrition for Healthy Living cohortJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20064347548217019373

- TangAMSmitESembaRDImproved antioxidant status among HIV-infected injecting drug users on potent antiretroviral therapyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20002332132610836754

- KnoxTAZafonte-SandersMFields-GardnerCMoenKJohansenDPatonNAssessment of nutritional status, body composition, and human immunodeficiency virus-associated morphologic changesClin Infect Dis200336 Suppl 2S63S6812652373

- GropperSSSmithIGroffIThe antioxidant nutrients, reactive species, and diseaseAdvanced Nutrition and Human MetabolismBelmont, CAWadsworth2005368377

- Cunningham-RundlesSMcNeeleyDFMoonAMechanisms of nutrient modulation of the immune responseJ Allergy Clin Immunol20051151119112815940121

- ScrimshawNSSanGiovanniJPSynergism of nutrition, infection, and immunity: an overviewAm J Clin Nutr199766464S477S9250134

- BhallaAKAmentoEPClemensTLHolickMFKraneSMSpecific high-affinity receptors for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: presence in monocytes and induction in T lymphocytes following activationJ Clin Endocrinol Metab198357130813106313738

- AdamsJSChenHChunRSubstrate and enzyme trafficking as a means of regulating 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D synthesis and action: the human innate immune responseJ Bone Miner Res200722Suppl 2V2024 Review18290716

- BatterhamMGoldJNaidooDA preliminary open label dose comparison using an antioxidant regimen to determine the effect on viral load and oxidative stress in men with HIV/AIDSEur J Clin Nutr20015510711411305623

- JarugaPJarugaBGackowskiDSupplementation with anti-oxidant vitamins prevents oxidative modification of DNA in lymphocytes of HIV-infected patientsFree Radic Biol Med20023241442011864781

- AustinJSinghalNVoigtRfor the CTN 091/CRIR Carotenoids Study GroupA community randomized controlled clinical trial of mixed carotenoids and micronutrient supplementation of patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency SyndromeEur J Clin Nutr2006601266127616721396

- BurbanoXMiguez-BurbanoMJMcCollisterKImpact of a selenium chemoprevention clinical trial on hospital admissions of HIV-infected participantsHIV Clinical Trials2002348349112501132

- ClarkRHFelekeGDinMNutritional treatment for acquired immunodeficiency virus-associated wasting using beta-hydroxy beta-methylbutyrate, glutamine, and arginine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr20002413313910850936

- de CaterinaRBastaGN-3 fatty acids and the inflammatory response – biological backgroundEur Heart J20013 Suppl DD42D49

- HellersteinMKWuKMcGrathMEffects of dietary n-3 fatty acid supplementation in men with weight loss associated with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: relation to indices of cytokine productionJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol19961132582708603262

- YoungJSHIV and medical nutrition therapyJ Am Diet Assoc19979710 Suppl 2S161S1669336581

- BellSJChavaliSBistrianBRConnollyCAUtsunomiyaTForseRADietary fish oil and cytokine and eicosanoid production during human immunodeficiency virus infectionJPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr19962043498788262

- SchwenkAKremerGBeckerKEnteral nutrition in AIDS cachexia: controlled study on the role of fiber [abstract no. We.B.3262]Int Conf AIDS199611102

- WilliamsSBBartschGMuurahainenNCollinsGRaghavanSSWheelerDProtein intake is positively associated with body cell mass in weight-stable HIV-infected menJ Nutr20031331143114612672933

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of MedicineDietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino AcidsWashington (DC)National Academy Press2002936967

- US Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of AgricultureReport of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 [Updated 2010 July 13]. Available from: http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-DGACReport.htmAccessed Jul 29, 2010

- Cunningham-RundlesSTrace element and mineral nutrition in HIV infection and AIDSBogdenJDKlevayLMClinical Nutrition of the Essential Trace Elements and MineralsTotowa, NJHumana Press2000333351

- DrainPKKupkaRMugusiFFawziWWMicronutrients in HIV-positive persons receiving highly active antiretroviral therapyAm J Clin Nutr20078533334517284727

- AllenLHPeersonJMOlneyDKProvision of multiple rather than two or fewer micronutrients more effectively improves growth and other outcomes in micronutrient-deficient children and adultsJ Nutr200913910221030 Epub 2009 Mar 2519321586

- IrlamJHVisserMERollinsNSiegfriedNMicronutrient supplementation in children and adults with HIV infectionCochrane Database of Syst Rev200519CD00365016235333

- MuellerNJFuxCALedergerberBfor Swiss HIV Cohort StudyHigh prevalence of severe vitamin D deficiency in combined antiretroviral therapy-naive and successfully treated Swiss HIV patientsAIDS2010241127113420168200

- MehtaSGiovannucciEMugusiFMVitamin D status of HIV-infected women and its association with HIV disease progression, anemia, and mortalityPLoS One20105e877020098738

- BogdenJDOleskeJMThe essential trace minerals, immunity, and progression of HIV-1 infectionNutr Res2007276977

- BaumMKCampaALaiSLaiHPageJBZinc status in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and illicit drug useClin Infect Dis200337 Suppl 2S117S12312942385

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of MedicineDietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and ZincWashington (DC)National Academy Press2002770773

- FawziWMsamangaGHunterDRandomized trial of vitamin supplements in relation to transmission of HIV-1 through breastfeeding and early child mortalityAIDS2002161935194412351954

- HumphreyJHIliffPJMarindaETEffects of a single large dose of vitamin A, given during the postpartum period to HIV-positive women and their infants, on child HIV infection, HIV-free survival, and mortalityJ Infect Dis200619386087116479521

- World Health OrganizationNutrient requirements for people living with HIV/AIDS: report of a technical consultationGenevaWorld Health Organization2003513–15

- ColbertLHVisserMSimonsickEMPhysical activity, exercise, and inflammatory markers in older adults: findings from the Health, Aging and Body Composition StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc2004521098110415209647

- PateRRPrattMBlairSNPhysical Activity and Public Health – a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports MedicineJAMA19952734024077823386

- WellenKEHotamisligilGSInflammation, stress and diabetesJ Clin Invest20051151111111915864338

- ShimizuKKimuraFAkimotoTEffect of moderate exercise training on T-helper cell subpopulations in elderly peopleExerc Immunol Rev200814243719203082

- StarkieROstrowskiSRJauffredSFebbraioMPedersenBKExercise and IL-6 infusion inhibit endotoxin-induced TNF-alpha production in humansFASEB J20031788488612626436

- JankordRJemioloBInfluence of physical activity on serum IL-6 and IL-10 levels in healthy older menMed Sci Sports Exerc20043696096415179165

- TanwaniLKMokshagundamSLLipodystrophy, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease in human immunodeficiency virus infectionSouth Med J200318018812630645

- KosmiskiLKuritzkesDHamiltonJFat distribution is altered in HIV-infected men without clinical evidence of the HIV lipodystrophy syndromeHIV Med200323524012859322

- MillerTLSomarribaGKinnamonDDThe effect of a structured exercise program on nutrition and fitness outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected childrenAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses20102631331920218880

- MillerTLA hospital-based exercise program to improve body composition, strength, and abdominal adiposity in 2 HIV-infected childrenAIDS Read20071745045217902228

- LindegaardBHansenTHvidTThe effect of strength and endurance training on insulin sensitivity and fat distribution in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with lipodystrophyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20083860386918628529

- SouzaPMJacob-FilhoWSantarémJMSilvaARLiHYBurattiniMNProgressive resistance training in elderly HIV-positive patients: does it work?Clinics (Sao Paulo)20086361962418925321

- Crum-CianfloneNRoedigerMPEberlyLfor Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program HIV Working GroupIncreasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemicPLoS One20105e1010620419086

- AmorosaVSynnestvedtMGrossRA tale of 2 epidemics: the intersection between obesity and HIV infection in PhiladelphiaJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20053955756116044007

- SamarasKWandHLawMEmerySCooperDCarrAPrevalence of metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy using International Diabetes Foundation and Adult Treatment Panel III criteria: associations with insulin resistance, disturbed body fat compartmentalization, elevated C-reactive protein, and [corrected] hypoadiponectinemiaDiabetes Care200711311917192343

- Crum-CianfloneNFRoedigerMEberlyLEfor Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program HIV Working GroupObesity among HIV-infected persons: impact of weight on CD4 cell countAIDS2010241069107220216300

- FordESLiCSattarNMetabolic syndrome and incident diabetes: current state of th evidenceDiabetes Care2008311898190418591398

- BahceciMGokalpDBahceciSTuzcuAAtmacaSArikanSThe correlation between adiposity and adiponectin, tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6 and high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels. Is adipocyte size associated with inflammation in adults?J Endocrinol Invest20073021021417505154

- LordGMLeptin as a proinflammatory cytokineContrib Nephrol200615115116416929139

- Berger-GreensteinJACuevasCABradySMMajor depression in patients with HIV/AIDS and substance abuseAIDS Patient Care and STDS20072194295518154491

- Ramírez-MarreroFASmithBAMeléndez-BrauNSantana-BagurJLPhysical and leisure activity, body composition, and life satisfaction in HIV-positive Hispanics in Puerto RicoJ Assoc Nurses AIDS Care200415687715296660

- VeljkovicMDopsajVStringerWWAerobic exercise training as a potential source of natural antibodies protective against human immunodeficiency virus-1Scand J Med Sci Sports20102046947419538533

- BroadbentSGassGAerobic training increases the stimulated percentage of CD4+CD25+ in older men but not older womenEur J Appl Physiol2008103798718204854

- BoppCMPhillipsKDFulkLJDudgeonWDSowellRHandGAPhysical activity and immunity in HIV-infected individualsAIDS Care20041638739315203431

- RoubenoffRSkolnikPRShevitzAEffect of a single bout of acute exercise on plasma human immunodeficiency virus RNA levelsJ Appl Physiol1999861197120110194203