Abstract

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a leading cause of death, especially in immunocompromised patients. The lack of clear prevalence data in the Middle East makes it difficult to estimate the true morbidity and mortality burden of HCV. In Kuwait, estimating the burden of disease is complicated by the constant flow of expatriates, many of whom are from HCV-endemic areas. The development of new and revolutionary treatments for HCV necessitates the standardization of clinical practice across all healthcare institutions. While international guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) do address this evolving treatment landscape, the cost-driven treatment prioritization of patients by these guidelines and unique HCV genotype presentation in the Kuwaiti population prompted the development of a more tailored approach. The predominant HCV genotypes prevalent in Kuwait are genotypes 4 and 1. The Kuwait Hepatology Club (KHC), comprising hepatologists across all major institutions in Kuwait, conducted several consensus meetings to develop the scoring criteria, evaluate all current evidence, and propose screening, diagnosis, and treatment suggestions for the management of HCV in this population. While these treatment suggestions were largely consistent with the 2016 AASLD and 2015 EASL guidelines, they also addressed gaps in the unmet needs of the Kuwaiti population with HCV.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

The prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was recently estimated as 2.8% worldwide, amounting to >185 million people,Citation1 and has rapidly become a leading cause of death, especially in HIV-positive patients.Citation2 In the Middle East, where countries have varying degrees of health service infrastructure, there is a distinct lack of clear epidemiology data. Most epidemiological studies have been conducted by independent scientists and are based on the seroprevalence of HCV in specific groups.Citation3 Many foreign workers in Kuwait are coming from regions that are considered HCV endemic. HCV prevalence in Kuwait is estimated to be around 0.8% in Kuwaiti nationals and 5.4% in expatriates.Citation4 The prevailing genotypes are genotypes 1 and 4, with genotype 4 as the most common.Citation5

Historically, options for HCV treatment have been limited. Interferon (IFN)-α and ribavirin (RBV), the main options, had inadequate efficacy results and severe adverse effects. However, in recent years, dramatic improvements in the therapeutic landscape have vastly improved the outcomes for the patients with chronic HCV. This quickly multiplying new generation of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) poses a unique challenge to healthcare governing bodies who must keep up with the rapid pace of therapy development. International guidelines created by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)Citation6 and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL)Citation7 are regularly updated with general recommendations for the management of patients with HCV. DAAs have introduced a promising new era of shortened HCV therapy, free of adverse events associated with previous standard therapies like IFNs. However, the genetic diversity of HCV in different regions and the lagging approval pace of new therapies mean that these recommendations must be tailored to the local population.

There are no recommendations yet for the management of HCV infection in Kuwait. The purpose of this article is to assist hepatologists and other healthcare professionals in the optimum management of patients with chronic HCV within the current national regulatory and therapeutic landscape in Kuwait.

Methods

The Kuwait Hepatology Club (KHC) includes representatives from the following six major hospitals that treat HCV infections in Kuwait: Mubarak Alkabir Hospital, Al-Amiri Hospital, Al-Jahraa Hospital, Al-Adan Hospital, Al-Sabah Hospital, and Farwaniya Hospital. From September 14, 2015, the KHC conducted three consensus meetings to draft an expert opinion on hepatitis C treatment in Kuwait. During these meetings, evidence from published literature and international guidelines (ie, from AASLD and EASL) was combined with real-world experience from the KHC’s expert panel to tailor the international recommendations to the local Kuwaiti clinical practice. Therefore, these statements should be viewed as the preferred approaches to care of the expert panel, rather than guidelines. The robustness of evidence was assessed for its quality and its relevance to Kuwaiti clinical practice patterns. Scoring criteria were adapted from AASLDCitation6 and EASLCitation7 guidelines ().

Table 1 Scoring criteria developed by the KHC

Diagnosis of acute and chronic HCV

The diagnosis of HCV infection is accomplished by immunoserologic assays and nucleic acid tests.Citation8 The most commonly used immunoserologic test is the third-generation ELISA. It is easy to perform and inexpensive, making it a suitable initial test for diagnosing HCV infection. However, this antibody test has several limitations.Citation9 For instance, in acute infection, it may take 8 weeks for seroconversion to take place.Citation10 Moreover, in immunocompromised settings (ie, in organ transplant recipients, hemodialysis, and HIV patients), seroconversion may be hampered, limiting the use of anti-HCV assays in the initial diagnosis.Citation11 Therefore, a nonreactive anti-HCV test will not definitively rule out infection in these patients. The detection of antibodies indicates one of the following: 1) current infection; 2) past infection that has resolved; and 3) false positivity.Citation12 Nucleic acid testing, using a highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for detecting HCV RNA, is more expensive and more technically demanding than the immunoserologic tests. Detecting HCV RNA indicates current infection.Citation11 Therefore, the KHC’s expert panel suggested repeatedly testing after 3 months to rule out current infection.

The KHC’s expert panel also suggested anti-HCV antibody assay as a first-line test in patients suspected of acute HCV (). If negative, the test should be repeated after 6–12 weeks to rule out seroconversion. Alternatively, if the initial antibody test is negative, testing for HCV RNA by PCR can be performed immediately and repeated after 12 weeks. In immunocompromised individuals, both anti-HCV and PCR should be performed as first-line tests and should be repeated 12 weeks later. In cases where chronic infection is suspected, the KHC’s expert panel suggested starting with the antibody test. All reactive tests should be confirmed by PCR to diagnose current infection definitively. If HCV RNA is negative, PCR should be repeated after 12 weeks.

Table 2 Workshop: Kuwait standard of practice for diagnostics tests

Screening for hepatitis C infection

The AASLD guidelines suggest screening select high, such as individuals who inject drugs, hemodialysis patients, healthcare workers, children born to HCV-infected women, HIV-infected individuals, individuals who received blood or blood products before 1992, and those born between 1945 and 1965.Citation6 The AASLD and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) do not recommend testing average-risk individuals.Citation6,Citation10–Citation12

While endorsing the AASLD and CDC screening guidelines, the KHC’s expert panel took into consideration data suggesting that targeted screening may miss a significant proportion of infected individuals and expanding screening practices to the general population may be cost-effective.Citation13 Currently, the Ministry of Health in Kuwait includes testing for HCV infection in the mandatory premarital and preemployment medical screening protocols, the practice that the KHC members find meritorious. For screening purposes, the panel suggested using the antibody test initially. If positive, current infection should be confirmed by PCR using another blood sample. A negative antibody test does not warrant further testing ().

Pretherapeutic assessments

It is important to determine comorbid conditions and disease severity for the implementation of corrective actions and to tailor therapy. Noninvasive tests and liver function tests are important to determine the fibrotic damage to the liver.Citation6 The KHC voted that routine liver stiffness measurements and liver function tests are necessary to assess disease severity. It is also important to determine at-risk behaviors, alcohol consumption, underlying comorbidities, and hepatitis B virus, or HIV co-infection to differentially assess patient disease severity. However, liver biopsies or histology examinations are rarely performed and testing for IL-28 genotypes was deemed unnecessary.

Goals and endpoints of HCV therapy

The ultimate goal of HCV therapy, as defined by AASLD, is to cure HCV infection and to prevent hepatic cirrhosis, decompensation of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, severe extra-hepatic manifestations, and death.Citation6 Achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR), as a therapeutic endpoint, in HCV-infected patients will reduce all-cause mortality and the consequences of liver-related disease, including end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Treatment of HCV

Therapeutic landscape

The HCV uses the nonstructural (NS) 3 protease and NS5A and NS5B polymerase enzymes for posttranslational processing and replication. These enzymes have become prime targets for HCV therapy. Protease inhibition interrupts posttranslational processing by blocking the catalytic site. In contrast, RBV monophosphate mimics inosine 5′-monophosphate and is a competitive inhibitor of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase, an enzyme involved in the de novo synthesis of guanine nucleotides. lists the therapeutic regimens currently approved and applied in Kuwaiti clinical practice.

Table 3 Therapies currently available in Kuwait

Expert opinion on genotype-specific therapy

The most common genotypes are genotypes 4 and 1.Citation5 Treatment options for both are summarized in , with 12 weeks being the most popular duration for most regimens. Consistent with the AASLD 2016 updated guidelines, the KHC suggested moving away from 24-week regimens unless a case is difficult to treat.

Table 4 Summary of KHC treatment suggestions for GT1, GT4, and special populations

High evidence grading (A1) was given to the AASLD-approved regimens for treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients, with some caveats. Grazoprevir/ elbasvir, although approved by the European Medical Agency (EMA), is not yet available in Kuwait so is not mentioned in this expert opinion. The simeprevir (SIM)/ sofosbuvir (SOF) regimen has been deprioritized because the Q80K screening test is not available in Kuwait, making it difficult to predict a positive outcome for these noncirrhotic patients.

Genotype 1

Paritaprevir/ritonavir-ombitasvir and dasabuvir (PrOD) in treatment-naive patients

Paritaprevir is a protease inhibitor (PI) that is administered with ritonavir, ombitasvir is an NS5a inhibitor, and dasabuvir is a nonnucleoside analog polymerase inhibitor. This regimen is approved in Kuwait for the treatment of genotype 1 patients and is frequently combined with RBV, except for genotype 1b cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients. Based on the updated 2016 AASLD guidelines and the following pivotal clinical trials, the KHC suggested PrOD plus RBV for 12 weeks in treatment-naive compensated cirrhotic genotype 1a patients with an evidence rating of A1 ().

The SAPPHIRE-I trial demonstrated 96% of SVR rates in treatment-naive noncirrhotic patients treated with PrOD plus RBV for 12 weeks.Citation14 These results were consistent with genotype 1a (95% of SVR) and genotype 1b (98% of SVR). Genotype 1b treatment-naive noncirrhotic patients achieved 99% of SVR rate in PrOD regimens with and without RBV.Citation15 Genotype 1a treatment-naive noncirrhotic patients achieved 90% of SVR with PrOD + RBV and 97% of SVR with PrOD–RBV. Another trial in cirrhotic patients, TURQUOISE-II, investigated the combination of PrOD and RBV for 12 and 24 weeks.Citation16 Consistent with the previous trial, 95% of treatment-naive patients achieved SVR in both groups. A subanalysis of genotypes 1a and 1b revealed 100% of SVR rates for genotype 1b in both arms, whereas genotype 1a achieved 92% at 12 weeks and 93% at 24 weeks.

PrOD in treatment-experienced patients

The KHC suggested the PrOD plus RBV regimen for 12 weeks in treatment-experienced noncirrhotic genotypes 1a and 1b patients, with an evidence rating of A1 based on the evidence from the SAPPHIRE II and TURQOISE II trials. However, in genotype 1a cirrhotic patients, PrOD plus RBV can be reserved as alternative therapy.

In the SAPPHIRE II trial, noncirrhotic patients previously treated with PEGylated IFN (PEG-IFN) and RBV (PEG/ RBV) achieved >95% of SVR in genotypes 1a and 1b on PrOD plus RBV treatment for 12 weeks.Citation17 The TURQUOISE-II trial revealed that genotype 1b cirrhotic patients who had failed prior treatments achieved 100% of SVR rates, irrespective of their previous treatment response, when treated with PrOD for 12 or 24 weeks.Citation16 Genotype 1a patients with an inadequate previous treatment response, however, did not achieve as significant an SVR rate (>80%).Citation18

SOF/ledipasvir (LDV) in treatment-naive patients

SOF is a nucleotide analog polymerase inhibitor and LDV is an NS5A inhibitor. In the ION-1 trial, treatment-naive patients achieved 97% of SVR at 12 weeks and 100% at 24 weeks. The ION-3 trial explored an 8-week regimen with SOF/LDV in combination with RBV.Citation19 With the exception of those patients with a low HCV viral load, more relapse cases were seen in the 8-week regimen and, thus, the KHC voted against this shortened duration of treatment.

SOF/LDV in treatment-experienced patients

Consistent with AASLD, the KHC suggested the use of SOF/ LDV in genotype 1 treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients, with an evidence rating of A1. In the ION-2 trial, SOF/LDV demonstrated significant SVR rates at both 12 (94%) and 24 (99%) weeks in treatment-experienced genotype 1 patients.Citation20 An integrated efficacy and safety analysis of >500 pooled Phases II and III cirrhotic treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients revealed significant response rates (96%) on a 12-week regimen of SOF/LDV with and without RBV despite previous therapy failure.Citation21

Daclatasvir (DAC) and SOF in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients

DAC is another NS5A inhibitor. The KHC suggested this regimen based on the following evidence, with a rating of A1. Sulkowski et alCitation22 conducted a trial of DAC/SOF in previously treated and untreated chronic HCV patients. Treatment-naive noncirrhotic patients achieved a high sustained viral response of undetectable HCV by 12 weeks (SVR12) of 98% with or without RBV. The ALLY-1 trial revealed that 82% of patients who had decompensated cirrhosis treated with DAC/SOF plus RBV for 12 weeks achieved SVR12.Citation16

SIM and SOF in treatment-naive patients

SIM is a PI. Based on the following evidence, the KHC suggested deprioritizing this regimen in treatment-naive, noncirrhotic patients, given that evidence published in favor of SIM/SOF was not conclusive enough to out value the existing alternative therapies (evidence rating: B2). SIM/ SOF in combination with RBV was investigated in the COSMOS trial for 12 and 24 weeks.Citation23 In treatment-naive patients, ~95% achieved SVR12 rates at 12 and 24 weeks. In a diverse, longitudinal, observational cohort, HCV-TARGET 2.0, 89% of patients achieved significant SVR4 rates after 12 weeks on SIM/SOF with or without RBV.Citation24 Genotype 1b patients had better SVR rates (95%) than genotype 1a patients (89%). Kwo et alCitation25 demonstrated in the OPTIMIST-1 trial that SIM/SOF-treated, treatment-naive, noncirrhotic patients achieved a high rate of SVR12 (97%), whereas cirrhotic patients achieved a lower SVR (85%). No difference was observed in Q80k resistance in these noncirrhotic types.Citation25 A TRIO cohort analysis also revealed that SIM/SOF-treated cirrhotic patients who were treatment naive achieved 88% of SVR when treated for 12 weeks with or without RBV.Citation16 Lawitz et alCitation26 discovered that genotype 1a patients with Q80K polymorphism achieved lower SVR (74%) than genotype 1a patients without the mutation (92%). The test for Q80K polymorphism is not currently available in Kuwait.

SIM and SOF in treatment-experienced patients

Similar to the treatment suggestions for treatment-naive patient for SIM/SOF, the KHC suggested deprioritizing this regimen in treatment-experienced patients based on the following evidence (evidence rating: B2). In the COSMOS trial, treatment-experienced patients achieved 91% of SVR rates when treated for 12 and 24 weeks.Citation15 The OPTIMIST-1 trial also demonstrated high SVR rates (95%) in treatment-experienced, noncirrhotic patients.Citation25 However, cirrhotic patients who had failed previous treatments only managed 77% of SVR. The TRIO cohort analysis revealed that SIM/ SOF-treated patients who were treatment experienced achieved 87% of SVR rates in noncirrhotic patients and 76% of SVR rates in cirrhotic patients.Citation16 The rate of SVR12 in PI failures was 82 and 80% in patients with the previous failure of PEG-IFN and RBV (PR) therapy.Citation16

Not recommended for genotype 1

Based on current evidence, other regimens such as SIM + PEG/RBV,Citation27–Citation29 SOF + PEG/RBV,Citation30,Citation31 telaprevir (TPV) + PEG/ RBV,Citation32 and boceprevir (BOC) + PEG/RBVCitation33,Citation34 are not more effective than the above regimens in duration or efficacy. Pending more robust data supporting the efficacy of these regimens, the KHC prioritized them as not recommended therapies (evidence rating: A1) ().

Regimens with PEG-IFN with RBV or with TPV or BOC are not recommended in patients with genotype 1.Citation6 In patients with decompensated cirrhosis with moderate-to-severe hepatic impairment (Child–Turcotte–Pugh [CTP] class B or C), IFN-based therapy and monotherapy with PEG/RBV-, DAA-, TPV-, BOC-, SIM-, or PrOD-based regimens are not recommended ().Citation6

Genotype 4

Paritaprevir/ritonavir-ombitasvir (PrO) and RBV

Consistent with AASLD and EASL, the KHC suggested the use of the PrO + RBV regimen for the treatment of genotype 4 patients, based on its strong evidence rating of A1. The AGATE I trial revealed that the PRO + RBV regimen achieved 97% of SVR rates in genotype 4 patients with cirrhosis.Citation35 The AGATE II trial focused on Egyptian patients with HCV who had cirrhosis.Citation36 Sensitivity analysis showed that PrO + RBV demonstrated the SVR12 rates of 97% (30/31) at 12 weeks and 96% (27/28) at 24 weeks in these patients excluding those who discontinue study drug prematurely with no on-treatment failure or those with missing follow-up data in the SVR12 window.Citation36 The PEARL-1 trial demonstrated that PrO + RBV was highly successful in achieving an SVR12 rate of 100% in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced, genotype 4 noncirrhotic patients.Citation37

SOF/LDV

In a proof-of-concept study, the SOF/LDV combination demonstrated 95% of SVR in 21 genotype 4 patients.Citation38 Another study in 44 patients with genotype 4 confirmed the SVR12 rate of 93%.Citation39 This regimen is preferred by the KHC for the treatment of genotype 4 patients (evidence rating: B1).

Not recommended for genotype 4

Regimens with PEG-IFN with RBV or with TPV or BOC are not recommended in patients with genotype 4 with or without cirrhosis based on the results from the PEARL-II and TURQOISE-III trials, respectively (evidence rating: A1).Citation40,Citation41

Special populations in genotype 1 and genotype 4

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis

DAC and SOF

Based on the following evidence, the KHC suggested DAC/ SOF for the treatment of decompensated cirrhosis in patients with genotype 1 HCV infection (evidence rating: A1). The ALLY-1 study demonstrated that a 12-week regimen of DAC/ SOF successfully treated genotype 1 patients with advanced cirrhosis (CTP class B and C; n=60) achieved the SVR rates of 83%.Citation42

SOF and LDV

Based on the following evidence, the KHC suggested SOF/ LDV for the treatment of patients with genotypes 1 or 4 HCV infection and decompensated cirrhosis (evidence rating: A1). In a large, multicenter, randomized controlled trial, SOLAR-1, 108 patients with HCV genotype 1 or 4 infection and who had decompensated cirrhosis (CTP class B or C) achieved the SVR rates of 87% (CTP B) and 86% (CTP C) when treated for 12 weeks. These rates were slightly improved when CTP B (89%) patients and CTP C patients (87%) received 24 weeks of SOF/LDV therapy.Citation43 Similar results were seen in a multicenter randomized controlled trial, SOLAR-2, of 108 patients with HCV genotypes 1 and 4 who had decompensated cirrhosis and achieved 87% of SVR after 12 weeks of treatment with SOF/LDV and 89% of SVR after 24 weeks.Citation44

Patients who have received liver transplants

SAC and SOF

Based on the following evidence, the KHC suggested DAC/ SOF for the treatment of postliver transplant patients with genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection (evidence rating: A1). The ALLY-1 study demonstrated that a 12-week regimen of DAC/ SOF-helped genotype 1 patients with recurrent HCV infection posttransplant achieved 94% of SVR12.Citation42 In another trial of 64 liver transplant recipients with HCV genotype 1 infection, patients treated with DAC/SOF achieved an SVR12 rate of 87%.Citation45

SOF and LDV

Based on the following evidence, the KHC suggested DAC/ SOF for the treatment of postliver transplant patients with genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection (evidence rating: A1). In the SOLAR-1 study, 223 liver transplant recipients with genotype 1 or 4 HCV infection achieved an SVR rate of 96% when treated with SOF/LDV for 12 or 24 weeks.Citation46

Patients with renal impairment

PrOD

Based on the following evidence, the KHC suggested the PrOD regimen for the treatment of patients with renal impairment, with the caveat that PrOD should be avoided in patients with CTP B or C (evidence rating: A1).

In a Phase II study of 20 patients with genotype 1 and stage 4 or 5 (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/ min/1.73 m2) CKD without cirrhosis, a PrOD combination regimen was administered with or without RBV.Citation47 All patients achieved SVR4. Regimens containing ofosbuvirCitation48 and SIMCitation49 have been found to be effective in mild CKD.

Genotypes 2, 3, 5, and 6

Genotypes 2, 3, 5, and 6 are very rare in Kuwait. KHC refers to the AASLD guidelines should patients present with any of these genotypes, with caveats for local availability of recommended therapy or testing options, as shown in .

Table 5 Summary of KHC treatment suggestions for genotypes 2, 3, 5, and 6

General suggestions for the management of HCV

Although the KHC’s expert panel suggestions were mostly consistent with AASLD, there were a few caveats.

Assessments prior to starting antiviral therapy

The AASLD recommends noninvasive testing and, in some cases, liver biopsies prior to starting antiviral therapy,Citation6 whereas in clinical practice, the KHC does not routinely include these tests. Instead, a “treat all” strategy is used to manage HCV infections (evidence rating: C1).Citation50

Assessments during antiviral therapy

The AASLD recommends discontinuing RBV therapy in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease whose hemoglobin levels drop <8.5 g/dL.Citation6 The KHC suggests that severe anemia needs not to be an indication to discontinue therapy (evidence rating: C1).Citation51

Suggested testing for diagnosing acute HCV infection

The KHC identified the preferred criteria for the diagnosis of acute HCV infection as

Positive anti-HCV IgG and a documented negative anti-HCV IgG in the previous 12 months, or

Positive serum HCV RNA test and a documented negative serum HCV RNA and negative anti-HCV IgG in previous 12 months, or

Positive serum HCV RNA test with an acute rise of alanine transaminase >5 times the upper limit of normal, or 3.5 times the high baseline alanine transaminase level with an absence of other causes of acute hepatitis.

Suggestions for medical management and monitoring in acute HCV infection

The KHC agreed with most of the AASLD recommendations for the medical management and monitoring of acute HCV infections, with one exception. Treatment of acute HCV infection after 24 weeks of presentation is not preferred except in special situations such as patients with CKD in whom spontaneous viral clearance is very uncommon.

Acute HCV infection in patients with CKD can progress very rapidly to cirrhosis. Treatment of acute HCV infection can be considered earlier in occupationally infected healthcare workers to prevent ongoing transmission events.

Follow-up for patients who achieve an SVR

The KHC suggested that patients with advanced liver fibrosis (stages F3–F4) should be monitored by FibroScan and other noninvasive methods (evidence rating: B1).Citation52 Patients with known or suspected bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis are at increased risk of developing complications of advanced liver disease and may require more frequent follow-up and surveillance by ultrasound.

Monitoring during chemotherapy and immunosuppression

The KHC determined that the major cause of death for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma is liver failure. Life expectancy may be compromised by underlying comorbidities. Functional improvement is important. Monitoring of HCV RNA is routinely practiced during chemotherapy (evidence rating: C1).

Suggestions for managing patients with risk factors (eg, obesity and alcoholism)

The KHC’s expert panel stated that multidisciplinary support involving diabetologists and dieticians is needed to manage these patients (evidence rating: A2).Citation53

Suggestions for monitoring quality of life (eg, patient-reported outcomes and work productivity)

The KHC’s expert panel observed that although an integrated care infrastructure is important to optimally manage patients with HCV, parameters for assessing the quality of life are not routinely measured due to the lack of adequate ancillary support (evidence rating: A2).Citation54

Suggestions for elderly patients

The KHC stated that the exclusion of elderly persons from HCV screening policy should be avoided. All people living with HCV infection should be considered for therapy, except those with a short-life expectancy (<6 months) due to nonliver-related or non-HCV-related comorbidities (evidence rating: B1).Citation55

Elderly patients should be a major topic in HCV epidemiology research, awareness campaigns, and targeted screening (evidence rating: C1).Citation56

In contrast to the AASLD guidelines, the KHC stated that HCV screening in elderly persons may be added to the screening colonoscopy program and may decrease viral transmission by colonoscopy. Use of shorter regimen courses, and avoidance of use of RBV because it has more adverse effects in elderly patients, is suggested (evidence rating: B2).Citation57 For people aged >50 years who are prescribed RBV-containing regimens, it is important to consider the complications of anemia and screen those who have a history of cardiovascular disease and who have had an electrocardiogram (ECG). For people with cardiovascular disease, a regimen that does not involve RBV may be most suitable (evidence rating: B2).Citation57

Suggestions for monitoring for pregnancy-related issues prior to and during antiviral therapy that includes RBV

In contrast to the AASLD, the KHC stated that antepartum HCV screening to decrease vertical transmission is preferred and may be cost-effective (evidence rating: C1).Citation58–Citation60 Delaying pregnancy until HCV antiviral therapy is completed should be considered, as treatment courses with DAAs are short in duration (evidence rating: A1).Citation61,Citation62 The KHC suggested two contraceptive measures. Patients treated with RBV should be counseled about the risk of teratogenicity, and patients of child-bearing age should be advised not to become pregnant during, and for 6 months after, therapy (evidence rating: A1).Citation63,Citation64

As the safety of DAAs during lactation has not yet been established, treating women who are breastfeeding is not recommended (evidence rating: A1).Citation61,Citation62

Suggestions for incarcerated individuals

Universal screening of incarcerated individuals is suggested (evidence rating: B1).Citation65 In fact, jails may be an ideal setting for identifying individuals with HCV infection (evidence rating: C2).Citation66,Citation67

In contrast to the AASLD, the KHC suggested a smooth transition process from HCV treatment within the prison to treatment in the community by official referral to regional hospitals without a lapse in treatment. Education on the importance of HCV screening and treatment in HCV high-prevalence community settings (ie, the jail population) is crucial to containing the spread of HCV. Incarceration presents a unique opportunity for HCV therapy, due to controlled access to healthcare and stable accommodation (evidence rating: C1).Citation68

Suggestions for persons who inject drugs (PWIDs)

Initial HCV RNA testing in PWIDs is suggested because an anti-HCV test is expected to be positive because of reinfection after spontaneous or treatment-related viral clearance (evidence rating: A1).Citation69–Citation71 In contrast to the AASLD, the KHC suggested that PWIDs can be successfully treated for HCV infection even with ongoing injection drug use (evidence rating: C2).Citation72 Suitable settings, specific models of care, and a multidisciplinary team approach have an important role in HCV treatment acceptance in PWIDs.Citation73–Citation78

Persons identified as abusing alcohol and as having alcohol dependence require treatment and consideration for referral to an addiction specialist (evidence rating: C2).Citation79 Integration of HCV therapy with addiction therapy in opioid substitution therapy centers is suggested to enhance HCV treatment uptake (evidence rating: C2).Citation74 Education and training of clinical staff at opioid substitution therapy centers to integrate HCV treatment with addiction treatment are suggested (evidence rating: B2).Citation6,Citation7

Body piercing procedures such as tattooing and Hijama should be monitored. Authorities should consider a needle-exchange program (evidence rating: B2).

Suggestions for emerging therapies

A difference in patient treatment patterns noted by the KHC is that the non-Kuwaiti population is mostly treated with generics rather than new direct-acting agents.

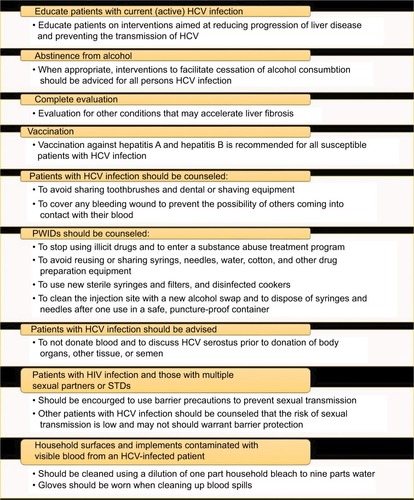

Common barriers to HCV

Despite advancements in the therapeutic landscape, barriers to achieving treatment goals, which are unique to HCV, exist locally. The KHC proposed the strategies listed in to overcome these barriers.

Table 6 Common barriers to HCV treatment and potential strategies to address these barriers

HCV carries a strong negative connotation as a sexually transmitted disease. The KHC’s expert panel highlighted the need for the education of healthcare providers and patients to counter the stigma associated with the disease. The need to create an expert group to influence government policy on HCV treatment was also suggested.

Patients may fear diagnosis because of misleading information about HCV being incurable. Another barrier is the cost and access to therapy. The club highlighted the immediate need to build a national registry to capture current and long-term detailed information on Kuwaiti patients with HCV. Collection of these data will help shape HCV management strategies. Additional measures discussed by the KHC to prevent the transmission of HCV are listed in .

Conclusion

HCV remains a pressing public health issue in Kuwait, but this expert opinion marks the first step in standardizing HCV treatment practices and maximizing patient benefit. The approval of new oral HCV therapies has expanded the possibilities of achieving unprecedented control of HCV infections. With this changing landscape, new challenges arise that require all healthcare and regulatory sectors to collaborate and design strategies to seamlessly and safely integrate these new therapies into existing treatment algorithms and improve patient access to these medications.

Acknowledgments

The following members of the Kuwait Hepatology Club (listed alphabetically by last name) contributed significantly to the writing and review of the article: Ali Abdulhamid (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Sabah Hospital), Bader Alenezi (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Jahra Hospital), Wafaa Alhashash (Gastroenterology and Hepatology unit, Al-Sabah Hospital), Raed Alzafiri (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Jahra Hospital), Ramadan Hassan Eldamarawy (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Adan Hospital), Ahmed Elfadhly (Haya Al-Habib Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Mubarak Alkabir Hospital), Hasan Elgarem (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Sabah Hospital), Amal Gad (Thunayan Al-Ghanim Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Al-Amiri Hospital), Amr Hamed (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Jahra Hospital), Fuad Hassan (Haya Alhabib Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Mubarak Alkabir Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University), Jafer Ismael (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Adan Hospital), Ali A Ismaiel (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Farwaniya Hospital, Kuwait), Tamer Mansour (Thunayan Al-Ghanim Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Al-Amiri Hospital), Sherif Saeed Mehrem (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Sabah Hospital), Samuel Sobhy Shaker (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, Al-Adan Hospital), and Heba Zaki (Thunayan Al-Ghanim Gastroenterology and Hepatology Center, Al-Amiri Hospital). We acknowledge Aarati Rai, PhD, MBA, OPEN Health Dubai, for providing medical writing support for this article. Medical writing support was funded by Abbvie. Abbvie had no contribution to the content of the article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Mohd HanafiahKGroegerJFlaxmanADWiersmaSTGlobal epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalenceHepatology20135741333134223172780

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort ColllaborationCauses of death in HIV-1-infected patients treated with antiretroviral therapy, 1996–2006: collaborative analysis of 13 HIV cohort studiesClin Infect Dis201050101387139620380565

- DawMADauAAHepatitis C virus in Arab world: a state of concernScientificWorldJournal2012201271949422629189

- AmeenRSanadNAl-ShemmariSPrevalence of viral markers among first-time Arab blood donors in KuwaitTransfusion200545121973198016371052

- PacsaASAl-MuftiSChughTDGenotypes of hepatitis C virus in KuwaitMed Princ Pract2001105567

- AASLD/IDSA HCV Guidance PanelHepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virusHepatology201562393295426111063

- European Association for Study of LiverEASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C 2015J Hepatol201563119923625911336

- European Association for Study of Liver, Asociacion Latinoamericana para el Estudio del H. EASL-ALEH Clinical Practice Guidelines: noninvasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosisJ Hepatol201563123726425911335

- ChouRClarkECHelfand M;US. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med2004140646547915023713

- WorkowskiKABolanGACenters for Disease Control and PreventionSexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015MMWR Recomm Rep201564RR-031137

- AlterMJKuhnertWLFinelliLCenters for Disease Control and PreventionGuidelines for laboratory testing and result reporting of antibody to hepatitis C virus. Centers for Disease Control and PreventionMMWR Recomm Rep200352RR-3CE11CE14

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionTesting for HCV infection: an update of guidance for clinicians and laboratoriansMMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2013621836236523657112

- CoffinPOScottJDGoldenMRSullivanSDCost-effectiveness and population outcomes of general population screening for hepatitis CClin Infect Dis20125491259127122412061

- FeldJJKowdleyKVCoakleyETreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirinN Engl J Med2014370171594160324720703

- FerenciPBernsteinDLalezariJABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCVN Engl J Med2014370211983199224795200

- A special meeting review edition: highlights in the treatment of hepatitis C virus from the 2014 liver meeting: a review of selected presentations. From the 2014 Liver Meeting November 7–11, 2014Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y)20141012 Suppl 6119

- ZeuzemSJacobsonIMBaykalTRetreatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirinN Engl J Med2014370171604161424720679

- PoordadFHezodeCTrinhRABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosisN Engl J Med2014370211973198224725237

- KowdleyKVGordonSCReddyKRLedipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosisN Engl J Med2014370201879188824720702

- AfdhalNReddyKRNelsonDRLedipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2014370161483149324725238

- ReddyKRBourliereMSulkowskiMLedipasvir and sofosbuvir in patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection and compensated cirrhosis: an integrated safety and efficacy analysisHepatology2015621798625846144

- SulkowskiMSGardinerDFRodriguez-TorresMDaclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infectionN Engl J Med2014370321122124428467

- LawitzESulkowskiMSGhalibRSimeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, to treat chronic infection with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 in non-responders to PEGylated interferon and ribavirin and treatment-naive patients: the COSMOS randomised studyLancet201438499561756176525078309

- SulkowskiMSVargasHEDi BisceglieAMEffectiveness of simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, in real-world patients with HCV genotype 1 infectionGastroenterology2016150241942926497081

- KwoPGitlinNNahassRSimeprevir plus sofosbuvir (12 and 8 weeks) in HCV genotype 1-infected patients without cirrhosis: OPTIMIST-1, a phase 3, randomized studyHepatology201664237038026799692

- LawitzEMatusowGDeJesusESimeprevir plus sofosbuvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis: a Phase 3 study (OPTIMIST-2)Hepatology201664236036926704148

- JacobsonIMDoreGJFosterGRSimeprevir with PEGylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2014384994140341324907225

- MannsMMarcellinPPoordadFSimeprevir with PEGylated interferon alfa 2a or 2b plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trialLancet2014384994141442624907224

- ReddyKRZeuzemSZoulimFSimeprevir versus telaprevir with PEGinterferon and ribavirin in previous null or partial responders with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (ATTAIN): a randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority phase 3 trialLancet Infect Dis2015151273525482330

- LawitzEMangiaAWylesDSofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infectionN Engl J Med2013368201878188723607594

- PearlmanBLEhlebenCPerrysMThe combination of simeprevir and sofosbuvir is more effective than that of PEGinterferon, ribavirin, and sofosbuvir for patients with hepatitis C-related Child’s class A cirrhosisGastroenterology20151484762770.e2 quiz.e11–225557952

- ZeuzemSAndreonePPolSTelaprevir for retreatment of HCV infectionN Engl J Med2011364252417242821696308

- PoordadFMcConeJJrBaconBRBoceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2011364131195120621449783

- BaconBRGordonSCLawitzEBoceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2011364131207121721449784

- AsselahTAGATE-I Study – Part I: OBV/PTV/r + RBV in genotype 4 with cirrhosis. Presented at EASL 2016J Hepatol201664Abs. SAT-278S827

- WakedIAGATE-II Study: OBV/PTV/r + RBV in genotype 4 Egyptian patients without or with cirrhosis. Presented at EASL 2016J Hepatol201664Abs. SAT-166S772

- HezodeCAsselahTReddyKROmbitasvir plus paritaprevir plus ritonavir with or without ribavirin in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C virus infection (PEARL-I): a randomised, open-label trialLancet201538599862502250925837829

- KohliAKapoorRSimsZLedipasvir and sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 4: a proof-of-concept, single-centre, open-label phase 2a cohort studyLancet Infect Dis20151591049105426187031

- AbergelAMetivierSSamuelDLedipasvir plus sofosbuvir for 12 weeks in patients with hepatitis C genotype 4 infectionHepatology20166441049105627351341

- FeldJJMorenoCTrinhRSustained virologic response of 100% in HCV genotype 1b patients with cirrhosis receiving ombitasvir/paritaprevir/r and dasabuvir for 12weeksJ Hepatol201664230130726476290

- AndreonePColomboMGEnejosaJVABT-450, ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir achieves 97% and 100% sustained virologic response with or without ribavirin in treatment-experienced patients with HCV genotype 1b infectionGastroenterology20141472359365.e110.3851/IMP303724818763

- PoordadFSchiffERVierlingJMDaclatasvir with sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C virus infection with advanced cirrhosis or post-liver transplantation recurrenceHepatology20166351493150526754432

- CharltonMEversonGTFlammSLLedipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for treatment of HCV infection in patients with advanced liver diseaseGastroenterology2015149364965925985734

- MannsMSamuelDGaneEJLedipasvir and sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in patients with genotype 1 or 4 hepatitis C virus infection and advanced liver disease: a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trialLancet Infect Dis201616668569726907736

- FontanaRJBrownRSJrMoreno-ZamoraADaclatasvir combined with sofosbuvir or simeprevir in liver transplant recipients with severe recurrent hepatitis C infectionLiver Transpl201622444645826890629

- WelzelTMReddyKRFlammSLOn-treatment HCV RNA in patients with varying degrees of fibrosis and cirrhosis in the SOLAR-1 trialAntivir Ther201621654154626891418

- PockrosPJReddyKRMantryPSEfficacy of direct-acting antiviral combination for patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and severe renal impairment or end-stage renal diseaseGastroenterology201615071590159826976799

- SaxenaVKoraishyFMSiseMESafety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in hepatitis C infected patients with impaired renal functionLiver Int201636680781626923436

- NazarioHENdunguMModiAASofosbuvir and simeprevir in hepatitis C genotype 1- patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis or GFR <30mL/minLiver Int201636679880126583882

- CasteraLSebastianiGLe BailBde LedinghenVCouzigouPAlbertiAProspective comparison of two algorithms combining non-invasive methods for staging liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis CJ Hepatol201052219119820006397

- CoppolaNDe PascalisSPisaturoMSustained virological response to antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C patients may be predictable by HCV-RNA clearance in peripheral blood mononuclear cellsJ Clin Virol201358474875024140030

- AfdhalNHBaconBRPatelKAccuracy of FibroScan, compared with histology, in analysis of liver fibrosis in patients with hepatitis B or C: a United States multicenter studyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2015134772779.e1-325528010

- OrtizVBerenguerMRayonJMCarrascoDBerenguerJContribution of obesity to hepatitis C-related fibrosis progressionAm J Gastroenterol20029792408241412358265

- HoSBBrauNCheungRIntegrated care increases treatment and improves outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and psychiatric illness or substance abuseClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201513112005201425724704

- Vespasiani-GentilucciUGalatiGGalloPDe VincentisARivaEPicardiAHepatitis C treatment in the elderly: new possibilities and controversies towards interferon-free regimensWorld J Gastroenterol201521247412742626139987

- CainelliFHepatitis C virus infection in the elderly: epidemiology, natural history and managementDrugs Aging200825191818184025

- YounossiZMStepanovaMNaderFHenryLPatient-reported outcomes of elderly adults with chronic hepatitis C treated with interferon-and ribavirin-free regimensJ Am Geriatr Soc201664238639326825683

- ElrazekAEAmerMHawaryBPrediction of HCV vertical transmission: what are factors should be optimized using data mining computational analysisLiver Int201737452953327125252

- TovoPACalitriCScolfaroCGabianoCGarazzinoSVertically acquired hepatitis C virus infection: correlates of transmission and disease progressionWorld J Gastroenterol20162241382139226819507

- PoliquinVYudinMHMurphyKEOkunNAntepartum screening for maternal infection and immune status: is it time to broaden our routine?J Obstet Gynaecol Can201537121118112126637086

- SperaAMEldinTKTosoneGOrlandoRAntiviral therapy for hepatitis C: has anything changed for pregnant/lactating women?World J Hepatol201681255756527134703

- GranotESokalEMHepatitis C virus in children: deferring treatment in expectation of direct-acting antiviral agentsIsr Med Assoc J2015171170771126757569

- JainSGoharkhayNSaadeGHankinsGDAndersonGDHepatitis C in pregnancyAm J Perinatol200724425125617447189

- FloreaniAHepatitis C and pregnancyWorld J Gastroenterol201319406714672024187446

- SpauldingACWeinbaumCMLauDTA framework for management of hepatitis C in prisonsAnn Intern Med20061441076276916702592

- LarneySKopinskiHBeckwithCGIncidence and prevalence of hepatitis C in prisons and other closed settings: results of a systematic review and meta-analysisHepatology20135841215122423504650

- BateJPColmanAJFrostPJShawDRHarleyHAHigh prevalence of late relapse and reinfection in prisoners treated for chronic hepatitis CJ Gastroenterol Hepatol20102571276128020594255

- KimAYNagamiEHBirchCEBowenMJLauerGMMcGovernBHA simple strategy to identify acute hepatitis C virus infection among newly incarcerated injection drug usersHepatology201357394495223111904

- HoferHWatkins-RiedelTJanataOSpontaneous viral clearance in patients with acute hepatitis C can be predicted by repeated measurements of serum viral loadHepatology2003371606412500189

- DoreGJHellardMMatthewsGVEffective treatment of injecting drug users with recently acquired hepatitis C virus infectionGastroenterology2010138112313519782085

- GrebelyJMatthewsGVPetoumenosKDoreGJSpontaneous clearance and the beneficial impact of treatment on clearance during recent hepatitis C virus infectionJ Viral Hepat2010171289620051007

- MartinNKVickermanPGrebelyJHepatitis C virus treatment for prevention among people who inject drugs: modeling treatment scale-up in the age of direct-acting antiviralsHepatology20135851598160923553643

- AspinallEJCorsonSDoyleJSTreatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysisClin Infect Dis201357Suppl 2S80S8923884071

- FragomeliVWeltmanMAddressing viral hepatitis in the opiate substitution setting: an integrated nursing model of careJ Gastroenterol Hepatol201530Suppl 2611

- AroraSThorntonKMurataGOutcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providersN Engl J Med2011364232199220721631316

- BakerDAlaviMErrattADelivery of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in the primary care settingEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol20142691003100925051216

- WadeAJMacdonaldDMDoyleJSThe cascade of care for an Australian community-based hepatitis C treatment servicePLoS One20151011e014277026562516

- HoSBBräuNCheungRIntegrated care increases treatment and improves outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and psychiatric illness or substance abuseClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2015131120052014.e1-325724704

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol2009 Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/ds10-alcohol.pdfAccessed February 2016