Abstract

It is becoming increasingly clear that quality of life (QOL) is impaired in those with chronic liver disease (CLD). One of the most important contributors to impaired QOL is the symptomatic burden which can range from slight to debilitating. Autonomic dysfunction accounts for a significant proportion of these symptoms, which can be common, non-specific and challenging to treat. Investigating the autonomic nervous system can be straight forward and can assist the clinician to diagnose and treat specific symptoms. Evidence-based treatment options for autonomic symptoms, specifically in CLD, can be lacking and must be extrapolated from other studies and expert opinion. For those with severely impaired quality of life, liver transplantation may offer an improvement; however, more research is needed to confirm this.

Introduction

With the ever-expanding population, improvements in treatment, and the subsequent improvement in survival, the chronic liver disease (CLD) population is expanding. While advancing prognosis may be considered beneficial for patients a longer life does not always equate to an improved quality of life.Citation1,Citation2 One of the major contributors to a poor quality of life in CLD is autonomic dysfunction (AD)Citation3–Citation5 and while the evidence base for the treatment of CLD continues to expand, the evidence for symptom control and palliation is being left behind.

Autonomic dysfunction is an impairment of the normal functioning of the autonomic nervous system that adversly affects health. It can be primary or secondsary, acute or chronic, and transient or progressive. This review will focus on chronic, secondary AD as a result of CLD. The prevalence of AD in CLD is as high as 67% in some populationsCitation6 and cannot therefore be ignored. Furthermore, the importance of AD is highlighted by its associated increase in mortality.Citation6 With this in mind it is essential that clinicians who care for people with CLD recognize when AD may be present, and which investigations and treatments may be of benefit.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Publications from 1950 to date were searched using OvidSP. Search terms used included ‘autonomic nervous system’ and ‘liver disease’. Excluding non-English papers 350 papers were identified. The resulting reference list of this paper is composed of articles reviewed and selected by both authors with additional relevant papers identified through reference lists. Where there is a lack of evidence in the literature regarding a specific point general principles and expert opinion are applied: these comments are explicit when included.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS)

The autonomic nervous system is complex and as yet not fully understood. The essential points will be discussed here to aid the clinical understanding of AD. The sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous systems (PNS) form the two arms of the ANS through which viscera, smooth muscle and secretory glands are controlled involuntarily.

Sympathetic preganglionic neurons release acetylcholine, whereas postganglionic neurons transmit noradrenaline (with the exception of sweat glands which are cholinergic, and the adrenal medulla which directly synapses with preganglionic neurons). The physiological responses of sympathetic nervous stimulation are increased heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP); dilatation of the bronchi; vasodilatation to skeletal muscle; vasoconstriction to the gastrointestinal tract; decreased gastrointestinal motility; increased sweating; smooth muscle sphincter contraction and pupillary mydriasis.

The neurotransmitter of the parasympathetic nervous system is acetylcholine, through which, under stimulation, the following clinical responses occur: decreased HR and contractility; vasodilation; bronchial constriction; increased gastrointestinal motility; relaxation of smooth muscle sphincters and pupilary miosis.

Pathogenesis

With the pathophysiology of CLD being so multifarious, the interaction it has with the ANS is difficult to fully appreciate. CLD results in complex changes in electrolyte homeostasis, altered regulation and response to vasocontrictors and dilators, changes to the arterio-venous circulation and other immunological and physiological changes which place additional stresses on autonomic function.

Liver disease results in a decreased response to vasoconstrictors which may be caused by increased concentration of vasodilators such as nitric oxide. An increase in portal blood pressure, even mild, can lead to an up-regulation of nitric oxide synthetase.Citation7 An increase in circulating vasodilators, a diseased liver and a portosystemic circulation bypassing hepatic metabolism will contribute to increased systemic vasodilatation. Circulating vasodilators will activate the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and increase plasma levels of the vasoconstrictor angiotensin II. In support of this theory is the increased plasma concentration of angiotensin II in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD).Citation8 Angiotensin II may interact with the parasympathic control of heart rate variability (HRV). Infusion of angiotensin II causes a decrease in HRV and a reduction in vagal discharges to the heart; if the vagus nerve is severed there is no change in H RV when it is infused. Administration of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor improves the HRV confirming that angiotensin II plays a role in AD.Citation9 In addition, administration of antioxidants seems to reverse blunted BP responses suggesting that oxidative stress may also play a role in AD.Citation10

AD is common in diabetic patients, and in those who suffer iatrogenic hypoglycemia there is a hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure (HAAF).Citation11 This is a result of decreased response of adrenaline and the SNS to hypoglycemia. It may be possible that the hypoglycemia induced by severe hepatic dysfunction may bring about HAAF. The resultant AD creates hypoglycemic unawareness, and therefore a vicious circle of worsening AD.Citation12

AD in advanced liver disease is associated with decreased baroreceptor sensitivity to hypotension, leading to impaired BP and HR responses.Citation13

Prevalence of AD in CLD

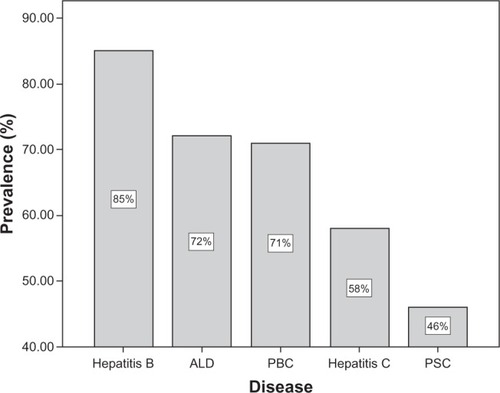

describes the prevalence of AD in specific CLD populations.

Figure 1 Prevalence of autonomic dysfunction in specific chronic liver diseases.Citation48–Citation52

Presentation of AD in CLD

Disease-specific features of AD are described in .

Table 1 Reported clinical features of autonomic dysfunction in chronic liver disease

The clinical picture of a patient with chronic liver disease presenting with AD is similar for AD of any cause. However, the presentation can be subtle, easily missed and with the aforementioned cardiovascular changes the presentation can be more complex and difficult to distinguish from other sequelae of CLD, such as hypovolemia.

Investigating the ANS

The simplest, clinical test for AD is to test for orthostatic hypotension (OH) by measuring lying and standing BP. A diagnosis of OH is made if there is a systolic drop in BP of ≥20 mm Hg or a diastolic drop of ≥10 mm Hg within 3 minutes.Citation14 A diagnosis of positional orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) can be made if there is a symptomatic increase in HR of ≥30 beats per minute (bpm) using the same postural challenge, in the absence of a BP drop.Citation15 In patients with CLD, before a diagnosis of OH is made, hypervolemia should be excluded. Typically hypovolemia will cause an isolated systolic drop with no diastolic drop in pressure, however this is unreliable.

Another simple clinical test is a resting electrocardiogram. A normal resting HR would lie between 60 and 80 bpm: levels above this could indicate parasympathetic dysfunction. However anemia, hyperthyroidism, sepsis, hypovolemia, arrhythmias and pheochromocytomas can also cause resting tachycardias. The presence of rate-limiting medication can also mask parasympathetic dysautonomia.

Symptom assessment tools are also available and may be more appropriate than physiologic testing where specialist equipment such as beat-to-beat BP and HR monitoring are not available. The Orthostatic Grading Scale (OGS) may be the most simple to use as it consists of only 10 items which are scored by patients according to the severity of postural symptoms.Citation16 It is widely used but has not been fully validated in the CLD population. A further disadvantage is that it only assesses symptoms of OH. Conversely, the Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale (COMPASS) is much more detailed and thorough in its assessment of systemic AD but at the price of being cumbersome, lengthy and more difficult to complete.Citation17

Other tests of autonomic function are available (see ), but these are specialized and not practicable in every clinic. However an understanding of them is of value in order to understand specialist investigation and research. Measuring autonomic function is unreliable in those patients who are on beta-blockers, as normal sympathetic responses will be blunted.

Table 2 Tests of autonomic function, and classification of severityCitation53

Treating AD in CLD

As there is currently no cure for dysautonomia, the principles of treatment are symptomatic. It is important to investigate and exclude reversible causes of symptoms masquerading as AD. For example a urinary tract infection can cause urinary symptoms, fatigue and tachycardia. There are numerous factors which complicate the management of dysautonomia in the patient with CLD. Patients may be on diuretics, beta-blockers, antidepressants or sedatives, all of which affect the autonomic nervous system. Lactulose and diuretics as discussed previously can contribute to incontinence or sexual dysfunction, and a risk/benefit analysis may need to be undertaken with the patient. An additional treatment which challenges the ANS is ascitic paracentesis. The reduction in intra-abdominal pressure can result in profound splanchnic vasodilation resulting in a prominent activation of the SNS leading to, at worst, circulatory collapse. This is avoided by infusion of intravenous albumin to maintain a normovolemic circulation.

Evidence is lacking for the treatment of dysautonomia in CLD and much must be extrapolated from the evidence relating to AD in general. In general conservative measures are recommended as first line treatment but when these fail specialist advice should be sought.

Specific dysautonomic symptoms

Orthostatic hypotension

One of the commonest consequences of AD in CLD is orthostatic hypotension (OH).Citation18 The patient typically complains of dizziness or lightheadedness on standing from a sitting or lying position. Other symptoms include blurring of vision, discomfort of head, neck or shoulder (the so called ‘coat hanger’ headache), fatigue, and in severe cases, syncope.

Patients with OH should try to maintain their intravascular volume by drinking at least 2–2.5 liters of fluid per day. This may however, complicate CLD, especially those who are fluid overloaded but who are unable to maintain their fluid in the intravascular compartment. Compression stockings help to redistribute extravascular fluid, and also prevent peripheral venous pooling on assuming an upright posture. Large meals should be avoided to minimize postprandial hypotension, and all patients should adopt a slow, gradual staged movement on rising into standing position. Pharmacological options are available for those few who do not respond to conservative measures. Fludrocortisone can improve OH by causing sodium and water retention, but caution is required in CLD where secondary hyperaldosteronism may already be present. Midodrine, which is used off-license in the United Kingdom, improves OH through agonist action on α1-adrenoreceptors. Extreme caution should be taken when used in patients with CLD, as it can worsen liver function. Other agents which have been used are beta-blockers, clonidine, pyridostigmine, erythropoietin and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Generally, the treatment of OH in the presence of portal hypertension is challenging.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a common complaint of patients with CLD and ranges from slight impairment of daily living to severe debilitation. Liver function tests (LFTs) are often performed in the patient who presents with ‘tiredness all the time’ and fatigue may therefore be a presenting symptom of CLD. It can develop at any time in patients with existing liver disease, but it does not correlate with disease severity.Citation19,Citation20 The severity of fatigue experienced by patients correlates with increasingly severe autonomic dysfunction, and must therefore be a major contributing factor in the etiology of this symptom.Citation21 Other contributing factors may include metabolic disturbance, anemia, altered sleep patterns and medication (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, beta-blockers).

In addition to fatigue, autonomic dysfunction can also reduce exercise tolerance. In patients with dysautonomia secondary to diabetes a blunted response of HR, BP, adrenaline and noradrenaline is seen.Citation22 The same response can be anticipated in those with AD in CLD.

Fatigue is often multi-factorial and difficult to manage. In CLD-associated fatigue, patients should be encouraged to adopt a steady state of activity, and avoid intense bouts of activity when energy is present. In resistant cases of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) where fatigue is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness modafinil has been used successfully.Citation23 It is relatively contraindicated in hypertensive patients, and BP should be monitored while on treatment. Starting dose is 50–100 mg and titrated accordingly. Side effects include headaches, sleep disturbance and hypertension. In those who suffer from insomnia a sedative may improve sleep thereby improving daytime wakefulness. In those who suffer broken sleep or display risk factors for sleep apnea a referral for sleep studies should be considered. In patients on beta-blockers a risk/benefit analysis should be undertaken on an individual basis, as beta-blockers can cause profound fatigue.

Urinary symptoms

Bladder dysfunction is a feature of AD; 14% of pre-transplant patients use incontinence pads.Citation24 Although there is very little data concerning bladder dysfunction in CLD we know from other AD associated diseases that it may also manifest as urinary frequency, hesitation or retention; the consequences of which include urinary tract infections, renal failure and indignity.Citation25 Incontinence is exacerbated by prescribing diuretics.

Gastrointestinal problems

In patients with CLD there is both delayed gastric emptying of liquids and solids and a prolonged transit time from mouth to cecum,Citation26,Citation27 symptoms include early satiety, nausea, vomiting, weight loss and epigastric pain. The decrease in small bowel motility resulting from AD is particularly important as it can cause bacterial overgrowth, with increased risk of encephalopathy and peritonitis. Delayed gastric emptying is associated with post-prandial hypoglycemia, and may therefore worsen AD.Citation28 Changes in gastrointestinal motility alongside disturbances of sphincter control can cause diarrhea, constipation and incontinence. Incontinence is exaggerated by prescribing laxatives.

Current treatments for delayed gastric emptying are, on the whole, disappointing. Medical management includes erythromycin which improves motility but does not improve symptoms, and domperidone which seems to be more effective at symptom control, in diabetic patients with gastroparesis.Citation29 Surgical options as yet are limited as trials have been retrospective and uncontrolled, but gastrostomy, botulinum neurotoxin and implantable electrodes to stimulate motility have shown promise.Citation29–Citation31

Gastrointestinal mobility disorders may be initially managed with diet, followed by medications such as laxatives or bulking agents, and constipating agents with planned enemas. For severe, resistant cases with significant impact on daily living surgical options exist. For incontinence the anal sphincter can be repaired or substituted, but with disappointing long term success.Citation32 For incontinence and constipation colectomy with or without stoma formation may improve symptoms.Citation33

The treatment of urinary problems caused by dysautonomia is limited; urodynamic studies will help direct appropriate management. First line treatment for urinary frequency includes bladder retraining (increasing time between voiding) or regular toileting (micturating every 2–4 hours). Pharmacological treatments include antimuscarinics which can worsen AD and alpha-blockers which can cause profound OH. For severely hypotonic bladders intermittent catheterization may reduce incontinence, infections and renal failure.Citation34

Sexual function

LFTs may be performed when investigating a patient who presents with sexual dysfunction, and may identify liver disease. Sexual problems may arise either from fatigue, altered body image, AD or from alterations in circulating sex hormones. Females show higher levels of dysfunction in end stage liver disease.Citation35 Diuretics, beta-blockers and antidepressants can all exacerbate sexual dysfunction.

It is difficult to distinguish between AD, medication adverse effects and psychological disturbance as the cause of sexual dysfunction. Contributing medications should be reviewed. Despite lower levels of testosterone and increased levels of estrogen, supplementing testosterone is not effective at improving erectile dysfunction.Citation36 Unsurprisingly, sexual dysfunction does improve in alcoholic men who abstain.Citation37 The incidence of erectile dysfunction more than doubles in men who undergo transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stenting.Citation38

Liver transplantation (LT) and autonomic function

The majority (87%) of patients who undergo liver transplantation suffer from AD.Citation39 The degree of dysautonomia improves after liver transplantation in 63% of patients at 6–7 months; however in a very small number it gets worse despite successful grafting,Citation39 and in patients whose allograft function is impaired, dysautonomia persists.Citation40 Although the aforementioned studies had relatively short follow-up studies of spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity have shown improvements which remain at 18 months.Citation41

The effects of LT on sexual and urinary dysfunction are much less impressive, with no improvements in symptoms. This confirms the complex nature of these problems with medication and psychological factors perhaps having a greater effect than AD.Citation24,Citation35

Prognosis

The association between liver disease severity and the incidence of AD is equivocal, with conflicting results.Citation6,Citation42–Citation44 Four-year mortality is 30% in people with CLD and dysautonomia compared to 6% in those with CLD and no dysautonomia.Citation45 AD is an independent risk factor for mortality in both compensated and decompensated cirrhotic patients.Citation6 In one study which followed patients awaiting LT for 10 months, 6 patients died. Each had AD, leading the authors to conclude that consideration should be given to early LT in those with AD.Citation6 In addition to increased mortality in those with cardiovascular abnormalities, patients with PBC who suffer from fatigue have an increased mortality.Citation46

The aforementioned sequelae of AD add significantly to poorer quality of life in patients already burdened with chronic disease. Recent studies are also beginning to define additional potential consequences of AD in those with liver disease such as cognitive impairment.Citation47 As dysautonomia is increasingly common in older age we should expect to see more consequences of AD as the liver disease population ages. Falls, OH, incontinence and cognitive impairment are all more common with age and will pose significant problems in this population.

Although the increase in mortality associated with AD is significant, hepatologists should not solely focus on survival, but address symptomatic burden and quality of life. Challenging, vague symptoms can often be improved through active listening and empathy, improving patients’ expectations and satisfaction. If patient care is to be improved, outcome measures which enable patients to represent the treatment effects which make a real difference to their lives must be incorporated into routine clinical practice.Citation5

Conclusion

Although greater understanding of the pathogenesis of AD in CLD is required, its effects on patients are becoming increasingly recognized. The symptomatic burden of patients with CLD and dysautonomia is high, but may be overlooked in favor of laboratory markers of disease severity. Many of the symptoms, such as fatigue and sexual dysfunction, pose difficulties for clinicians, as they may be considered low priority, ubiquitous and unmodifiable. Simple measures such as reviewing medications (beta-blockers, diuretics, and antidepressants) may lead to improvements in the patients’ symptoms and quality of life. Recognizing AD will help to identify those patients who are at increased risk of death, and may contribute to the consideration for LT.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MarchesiniGBianchiGAmodioPFactors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosisGastroenterology2001120117017811208726

- DavidKKowdleyKVUnalpAQuality of life in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: baseline data from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research networkHepatology20094961904191219434741

- NewtonJPairmanJWiltonKJonesDEDayCFatigue and autonomic dysfunction in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseaseClin Auton Res200919631932619768633

- KramerLHoferHBauerERelative impact of fatigue and subclinical cognitive brain dysfunction on health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C infectionAIDS200519Suppl 3S85S9216251834

- JonesDEJSutcliffeKPairmanJWiltonKNewtonJLAn integrated care pathway improves quality of life in primary biliary cirrhosisQJM2008101753554318388154

- FleckensteinJFFrankSThuluvathPJPresence of autonomic neuropathy is a poor prognostic indicator in patients with advanced liver diseaseHepatology19962334714758617426

- AbraldesJGIwakiriYLoureiro-SilvaMHaqOSessaWCGroszmannRJMild increases in portal pressure upregulate vascular endothelial growth factor and endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the intestinal microcirculatory bed, leading to a hyperdynamic stateAm J Gastrointest Liver Physiol20062905G980G987

- ArroyoVPlanasRGayaJSympathetic nervous activity, reninangiotensin system and renal excretion of prostaglandin E2 in cirrhosis. Relationship to functional renal failure and sodium and water excretionEur J Clin Invest19831332712786409652

- DillonJFNolanJThomasHThe correction of autonomic dysfunction in cirrhosis by captoprilJ Hepatol1997263313359059954

- FerlitschAPleinerJMittermayerFVasoconstrictor hyporeactivity can be reversed by antioxidants in patients with advanced alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver and ascitesCrit Care Med20053392028203316148476

- CryerPEHypoglycemia in diabetes: pathophysiological mechanisms and diurnal variationProg Brain Res200615336136516876586

- CryerPEDiverse causes of hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in diabetesN Engl J Med2004350222272227915163777

- LhuillierFDalmasEDGratadourPMSpontaneous baroreflex cardiac sensitivity in end-stage liver disease: effect of liver transplantationEur J Anaesthesiol200623542643216507199

- AnonymousConsensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, pure autonomic failure, and multiple system atrophy. The Consensus Committee of the American Autonomic Society and the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology199646514708628505

- LowPAOpfer-GehrkingTLTextorSCPostural tachycardia syndrome (POTS)Neurology1995454 Suppl 5S19S257746369

- SchrezenmaierCGehrkingJAHinesSMLowPABenrud-LarsonLMSandroniPEvaluation of orthostatic hypotension: relationship of a new self-report instrument to laboratory-based measuresMayo Clin Proc200580333033415757013

- SuarezGAOpfer-GehrkingTLOffordKPAtkinsonEJO’BrienPCLowPAThe Autonomic Symptom Profile: A new instrument to assess autonomic symptomsNeurology199952352352810025781

- ChaudhryVCorseAMO’BrianRCornblathDRKleinASThuluvathPJAutonomic and peripheral (sensorimotor) neuropathy in chronic liver disease: a clinical and electrophysiologic studyHepatology19992961698170310347110

- NewtonJLJonesDEHendersonEFatigue in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is significant and associates with inactivity and excessive daytime sleepiness but not with liver disease severity or insulin resistanceGut200857680781318270241

- Cauch-DudekKAbbeySStewartDEHeathcoteEJFatigue in primary biliary cirrhosisGut19984357057109824355

- NewtonJLDavidsonAKerrSAutonomic dysfunction in primary biliary cirrhosis correlates with fatigue severityEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200719212513217272997

- BottiniPTantucciCSciontiLCardiovascular response to exercise in diabetic patients: influence of autonomic neuropathy of different severityDiabetologia19953822442507713321

- JonesDENewtonJLAn open study of modafinil for the treatment of daytime somnolence and fatigue in primary biliary cirrhosisAliment Pharmacol Ther200725447147617270003

- Gomez-LoboVBurganskyAKim-SchlugerLBerkowitzRGynecologic symptoms and sexual function before and after liver transplantationJ Reprod Med200651645746216846082

- HaenschCAJorgJAutonomic dysfunction in multiple sclerosisJ Neurol2006253Suppl 1I3I1916477484

- GalatiJSHoldemanKPDalrympleGVHarrisonKAQuigleyEMDelayed gastric emptying of both the liquid and solid components of a meal in chronic liver diseaseAm J Gastroenterol19948957087118172142

- GalatiJSHoldemanKPBottjenPLQuigleyEMGastric emptying and orocecal transit in portal hypertension and end-stage chronic liver diseaseLiver Transpl Surg19973134389377756

- OhlssonBMelanderOThorssonOOlssonREkbergOSundkvistGOesophageal dysmotility, delayed gastric emptying and autonomic neuropathy correlate to disturbed glucose homeostasisDiabetologia20064992010201416832660

- BloomgardenZTDiabetic neuropathyDiabetes Care200831361662118308684

- LacyBECrowellMDSchettler-DuncanAMathisCPasrichaPJThe treatment of diabetic gastroparesis with botulinum toxin injection of the pylorusDiabetes Care200427102341234715451898

- AbellTMcCallumRHockingMGastric electrical stimulation for medically refractory gastroparesisGastroenterology2003125242142812891544

- LehurPAGlemainPBruley des VarannesSBuzelinJMLeborgneJOutcome of patients with an implanted artificial anal sphincter for severe faecal incontinence. A single institution reportInt J Colorectal Dis199813288929638494

- KammMAHawleyPRLennard-JonesJEOutcome of colectomy for severe idiopathic constipationGut19882979699733396968

- ShamliyanTAKaneRLWymanJWiltTJSystematic review: randomized, controlled trials of nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in womenAnn Intern Med2008148645947318268288

- SorrellJHBrownJRSexual functioning in patients with endstage liver disease before and after transplantationLiver Transpl200612101473147716741902

- GluudCWantzinPEriksenJNo effect of oral testosterone treatment on sexual dysfunction in alcoholic cirrhotic menGastroenterology1988956158215873053314

- Van ThielDHGavalerJSSanghviARecovery of sexual function in abstinent alcoholic menGastroenterology19838446776826402410

- NolteWSchindlerCGFigullaHRIncrease of serum estradiol in cirrhotic men treated by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shuntJ Hepatol200134681882411451164

- CareyEJGautamMIngallTDouglasDDThe effect of liver transplantation on autonomic dysfunction in patients with end-stage liver diseaseLiver Transpl200814223523918236403

- McDougallAJDaviesLMcCaughanGWAutonomic and peripheral neuropathy in endstage liver disease and following liver transplantationMuscle Nerve200328559560014571462

- LhuillierFDalmasEDGratadourPMSpontaneous baroreflex cardiac sensitivity in end-stage liver disease: effect of liver transplantationEur J Anaesthesiol200623542643216507199

- HendrickseMTTrigerDRPeripheral and cardiovascular autonomic impairment in chronic liver disease: prevalence and relation to hepatic functionJ Hepatol1992161–21771831336506

- OliverMIMirallesRRubies-PratJAutonomic dysfunction in patients with non-alcoholic chronic liver diseaseJ Hepatol1997266124212489210610

- TrevisaniFSicaGBernardiMAutonomic neuropathy in advanced liver diseaseHepatology199624615498938197

- HendrickseMTThuluvathPJTrigerDRNatural history of autonomic neuropathy in chronic liver disease. [see comment]Lancet19923398807146214641351136

- JonesDEBhalaNBurtJGoldblattJPrinceMNewtonJLFour year follow up of fatigue in a geographically defined primary biliary cirrhosis patient cohortGut200655453654116299032

- NewtonJHollingsworthKTaylorRCognitive impairment in primary biliary cirrhosis: Symptom impact and potential etiologyHepatology200848254154918563843

- SzalayFMartonAKeresztesKHermanyiZSKemplerPNeuropathy as an extrahepatic manifestation of chronic liver diseasesScand J Gastroenterol Suppl19982281301329867123

- NewtonJLGibsonGJTomlinsonMWiltonKJonesDFatigue in primary biliary cirrhosis is associated with excessive daytime somnolenceHepatology2006441919816800007

- NewtonJLHudsonMTachtatzisPPopulation prevalence and symptom associations of autonomic dysfunction in primary biliary cirrhosisHepatology20074561496150517538969

- LindgrenSLiljaBVerbaanHSundkvistGAlcohol abuse exaggerates autonomic dysfunction in chronic liver diseaseScand J Gastroenterol19963111112011248938907

- MonforteREstruchRValls-SoleJNicolasJVillaltaJUrbano-MarquezAAutonomic and peripheral neuropathies in patients with chronic alcoholism. A dose-related toxic effect of alcoholArch Neurol199552145517826275

- EwingDJClarkeBFAutonomic neuropathy: its diagnosis and prognosisClin Endocrinol Metab19861548558883536203