Abstract

Objectives

People with a history of injecting drugs have high prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and many have opioid use disorder (OUD). Modern HCV therapies with improved efficacy and tolerability are available, but access is often limited for this group, who may be underserved for health care and face social inequity. This work develops practical steps to improve HCV care in this population.

Methods

Practical steps to improve HCV care in OUD populations were developed based on clinical experience from Spain, structured assessment of published evidence.

Results

Options for improving care at engagement/screening stages include patient education programs, strong provider–patient relationship, peer support, and adoption of rapid effective screening tools. To facilitate work up/treatment, start options include simplified work up process, integration of HCV and OUD care, and continuous psychosocial support prior, during, and after HCV treatment.

Conclusion

It is important to plan on local basis to set up a joint integrated approach between specific drug treatment services and local points of HCV care. The elements for a specific integrated program should be chosen from options identified, including education services, peer input, organization to make HCV screening and treatment easier by co-location of services, and wider access to prescribing direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy.

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is common in people with a history of injecting drugs and opioid use disorder (OUD).Citation1,Citation2 In Europe, it is estimated that 2–3 million individuals have a lifetime history of injecting drug use, including 1.5 million who have a recent history of OUD.Citation2 HCV infection is prevalent in 14–84% of such groups.Citation3 Despite high prevalence, individuals in these groups are often marginalized and have limited access to general health care.Citation4 Increasing mortality/morbidity due to advanced liver disease defines a major public health problem among people with a history of injecting drugs and OUDCitation5 and calls for enhanced access to HCV care for such a marginalized population.Citation6

Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs indicated for HCV treatment, with improved efficacy, safety profile, and tolerability, when compared with interferon-based regimens, have transformed outcomes.Citation7 DAA regimens are effective in patients receiving opioid agonist therapy (OAT)/opioid substitution therapy (OST) for OUD.Citation8–Citation10 Many people with a history of injecting drugs are engaged with OUD treatment servicesCitation11; in Europe, the proportion of engagement with OUD care is 40–90%.Citation12 In Spain, an estimated 60–80,000 people are engaged with OUD treatment services,Citation2 of whom 50–80% are infected with HCV.Citation2,Citation13 OUD care is often provided by social services, municipal authorities, or the national health service, in different settings within each region or country.Citation2,Citation12,Citation13 These centers are separated from potential points of care for HCV.Citation12 In Spain and other countries, OUD treatment is provided in specialist-led, often standalone offices or clinics; HCV specialist services are not co-located in many cases.Citation5,Citation12 Local arrangements for HCV management clinical services are the responsibility of different parts of the health care system, including infectious diseases, internal medicine, and hepatology departments. These organizational factors limit the success of HCV care; social and provider-related barriers to HCV care are also significant.Citation14

The objective of this work is to identify practical steps to improve HCV treatment in people with a history of injecting drugs and OUD based on clinical experience and relevant evidence in this evolving area.

Methods

Evidence describing interventions that may improve outcomes in the management of HCV treatment in the context of OUD was collected and assessed. A structured approach to organize analysis was followed, applying an existing framework of a patient journey.Citation2,Citation15 This framework describes treatment in steps from potential initial presentation at a drug treatment service through steps of engagement, screening, work up/referral, and treatment ().

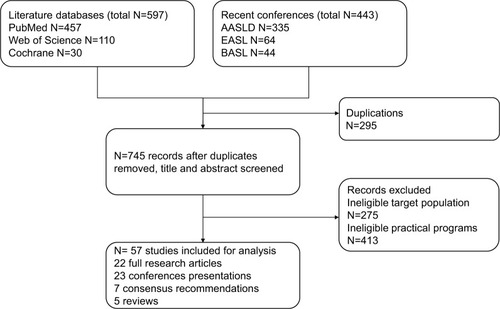

Figure 1 Summary of the process for literature search.

Evidence collection

A structured search of published literature from PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases was completed using a set of predefined search terms (). The search was restricted to publications after 2012, when the first DAA medications became available. A specific additional search of the proceedings of recent, relevant scientific expert meetings was completed to capture the most recent evidence. This focused on the major academic congresses of the leading professional societies, as identified by experts highly familiar with the therapy area. These included American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), and British Association for the Study of the Liver (BASL). Two reviewers familiar with structured literature searches and the therapy area assessed evidence independently and analyzed data. A total of 597 articles (PubMed =457, Web of Science =110, and Cochrane =30) and 443 abstracts (AASLD 2017=335, EASL 2017=64, and BASL 2017=44) were screened for relevance (). Studies were included if they described effective practice or policy interventions in improving care generally or for HCV specifically in people with a history of injecting drugs and OUD. Evidence from the literature review was then prioritized to identify most important practical steps to improve HCV care for people with OUD. Priorities were chosen by the authors (all with extensive clinical experience in HCV or OUD care) based on the opinion of potential impact. Interventions described in 57 studies, including 22 full research articles, 5 reviews, 23 abstracts/posters from conferences, and 7 consensus recommendations were chosen for analysis.

Table 1 Summary of keywords used in literature search

Results

A series of possible options for improving OUD care at each stage of the patient journey were defined based on an analysis of evidence obtained from the literature search and analysis (). Studies showing effective practical interventions for improving HCV care in such populations are summarized in . Results are described according to steps on the patient journey.

Table 2 Summary of effective practical interventions in improving HCV care in patients with a history of injecting drugs and OUD

Possible tactics to improve patient outcomes

Engagement

Low engagement may be addressed by education programs: for patients, options include brief group sessions at drug treatment services including workshops, Q&A sessions, leaflets, videos on the basics of HCV and risk behaviors for transmission, HCV treatment pathway, right of equal access,Citation16,Citation17 and interactive digital health decision aids.Citation18 Education sessions for health care professionals (HCPs) directed in primary careCitation19 and drug treatment services,Citation17 and HCV awareness campaigns directed to the general public may be of benefit. Programs that actively seek patients such as pop-up and short-term services delivered by clinics in neighborhoods with high HCV prevalence are effective in promoting treatment engagement.Citation20

Developing strong provider–patient relationships improves outcomes by creating an “enabling environment” and avoiding stigma.Citation21,Citation22 Peer support improves engagement with medical interventionsCitation23,Citation24 and can address potential mistrust and fear of discrimination.Citation25

Screening

Adoption of fast and effective screening methods improves efficiency. Dried blood spot testing (DBST) offers antibody testing and RNA confirmation in one stepCitation26 and can be effectively implemented in drug treatment services,Citation27–Citation29 alcohol clinics, prisons, needle equipment services,Citation28 or via out-reach mobile services.Citation30 A pretesting questionnaire-based screening tool helps identify people who may benefit most from testing in primary care.Citation31 Community-based active case finding with rapid antibody oral fluid test, either by peer facilitationCitation32 or by temporary clinics,Citation20 increases screening rate in high-risk populations. Targeted screening at general practices in areas of deprivation and high prevalence of injecting drug use,Citation33 or at drug treatment services, increases screening outcomes. For people with a history of injecting drugs who tested negative, it is important to offer routine testing every 12 months and following any high-risk injecting episode.Citation11,Citation34

Work up/referral

Simplified work up with access to noninvasive methods such as transient elastography (TE) (also known as Fibroscan) and serum biomarker tests accelerates the workup process and enables triage for immediate careCitation35–Citation37 implemented at drug treatment services, primary care, medically supervised injecting centers,Citation38 street-based outreach programs, or in prison.Citation37 Mobile TE further provides convenience in drug treatment servicesCitation29 or in mobile out-reach programs for hard-to-reach populations of drug users, prisoners, homeless, and psychiatric patientsCitation30 or at primary care.Citation39 Noninvasive serum bio-marker tests also eliminate many of the concerns associated with liver biopsy.Citation36 The aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), a calculated score predicting fibrosis,Citation37 is an effective prescreening tool to reduce the number of patients requiring Fibroscan.Citation37 Logistic support such as tailored flexible scheduling facilitates work up completion.Citation40

A tailored approach with different options for engagement is most likely to be successful.Citation40 Referral processes can be facilitated by education for HCP at drug treatment servicesCitation17 and primary care;Citation19 support from peer mentors facilitates linkage to start HCV treatment.Citation41

Treatment

A single-location clinic with access to a multidisciplinary team is effective in facilitating the progression from patient identification to HCV treatment.Citation20,Citation42 Integrated HCV treatment can be provided at primary care,Citation39,Citation43 drug treatment services,Citation39,Citation44 needle equipment services,Citation45 or prison.Citation46 It can be as a part of a traditional integrated treatment plan for OUD,Citation47,Citation48 or as a part of a combined program of integrated drug treatment, HCV, and needle equipment program,Citation49,Citation50 or for people who are actively injecting and not receiving integrated treatment for OUD.Citation45 Addiction specialists based in HCV clinicsCitation51 or mobile teams for screening, diagnosis, and treatment may address underserved populations.Citation30 Wider prescribing options for DAA including primary care physicians (PCPs) increases treatment access;Citation43,Citation52,Citation53 treatment can be delivered in nurse-led drug treatment services,Citation39,Citation54 primary care,Citation39,Citation55,Citation56 prison,Citation57 or pharmacist-led clinics.Citation58

Smartphone or desktop digital platforms assist clinical decision making and facilitate treatment initiation.Citation59 Tele-consultation is effective in overcoming physical barriers of having to meet with the HCV specialists.Citation60

Adherence to treatment can be facilitated with psychosocial support, such as continuous counseling,Citation61 case management services, actively screening for psychiatric comorbidities with referral to mental health providers including co-located specialists at HCV clinics and referral to peer-support groups with OUD care and buddy systems. Shorter treatment duration tailored to the population of injecting drug users may be effective.Citation62

Peer-led models combined with multidisciplinary care lead to improved knowledge, treatment uptake, and service provision.Citation23,Citation25 Contingency management, including monetary incentives, is effective in improving adherence to hepatitis B virus vaccinationCitation63 and promotes HCV treatment initiationCitation41 among people with a history of injecting drugs. Developing or implementing existing national strategies, action plans, and guidelines for HCV treatment in people with a history of injecting drugs helps establish best practices.Citation64

Re-infection risk is limited by long-term follow-up with access to multidisciplinary care and harm reduction services after HCV treatment.Citation65–Citation67 Regular HCV testing after the treatment and analysis of risk factors for re-infection is helpful for early engagement for potential interventions.Citation5,Citation11,Citation68,Citation69

Discussion

DAA regimens offer the possibility of cure for HCV. People with a history of injecting drugs and OUD represent a major group requiring HCV treatment but find it hard to access care. It is the opinion of the authors that it is essential, now, to address limits to therapy access if HCV treatment uptake is to be available to all and eradication of the infection is to be achieved. Many citizens with great need for HCV therapy cannot navigate pathways to get the HCV care they need. Law, policy, and guidelines in many European countries defines the equality of access to health care for all citizens and increasingly for HCV treatment – it is the reality that despite this and if action is not taken, many with the greatest needs will not be able to access proven treatment for a serious condition.

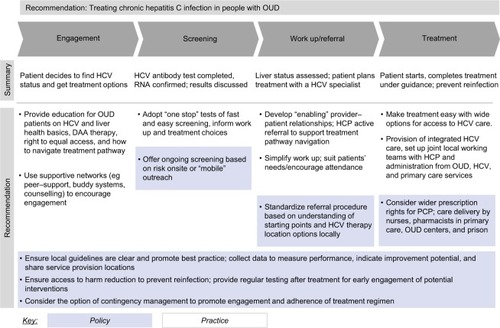

This structured assessment identifies practical steps from published evidence, which can improve HCV care in people with a history of OUD. Recommendations for practical steps to improve care are shown in and summarized here:

Provide peer-led education for patients with OUD including updates on HCV and liver health, DAA therapy, right of equal access to therapy, and how to navigate treatment pathways.Citation17,Citation18,Citation70

Develop “enabling” provider–patient relationshipsCitation22,Citation71,Citation72 to support HCV treatment pathway navigation.Citation19,Citation73

Standardize HCV referral procedure based on the understanding of starting points and treatment location options and use supportive networks (eg, peer support, buddy systems, counseling) to encourage engagement.Citation23–Citation25

Provide “one stop” fast and easy screening services, providing all necessary diagnostic information.Citation5,Citation27–Citation29 Offer ongoing screening based on risk onsite or with “mobile” outreach.Citation11,Citation20,Citation30,Citation33,Citation34

Simplify work up to encourage attendance; develop local capability with noninvasive liver assessment within drug treatment clinics.Citation29,Citation36,Citation38,Citation70

Make treatment easy with wide options for access to HCV care services. Implement wider prescription rights for PCPCitation43,Citation52 and care delivery by nurses and pharmacists in primary care, drug treatment services, and prison.Citation39,Citation43,Citation54,Citation57,Citation58

Provide integrated HCV care,Citation5,Citation11,Citation39,Citation42,Citation47,Citation51,Citation74 set up joint local working teams of HCP and administration from OUD, HCV, and PCP services focused on HCV treatment.

Review service results jointly to set standards of care and inform service development including “all under one roof ” models and develop local guidelines to promote best practice.Citation64

Collect data to measure performance, indicate improvement potential, share results among local service providers and locations.

Ensure continuing access to harm reduction to prevent reinfection; provide regular testing after treatment for the early engagement of potential interventions.Citation5,Citation11,Citation66–Citation68,Citation75

Figure 2 Practical recommendations for best practices of HCV treatment for people with OUD.

Abbreviations: DAA, direct-acting antiviral; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCP, health care professionals; PCP, primary care physician; OUD, opioid use disorder.

This recommendation is based on the clinical experience of clinicians with highly relevant long-term experience and interpretation of a review of current evidence. Evidence is collated from available published sources; this work is limited in this respect – in this evolving field, it is important to reconsider this work in the light of new evidence, in the future. Priorities are set based on clinical experience in Spain and observation of international practices. It is noted that the challenges for HCV and OUD treatment services are common in other countriesCitation12 and that the wide range of models of care and experience in managing HCV in Spain and its regions may be representative of the approach in many other countries. This work identifies practical steps based on clinical factors; there are other social and provider-related factors outside the scope of this article that are important to address in this population.

Conclusion

People with a history of injecting drugs engaged with OUD care services often face considerable barriers for HCV care. The recommendations advocated here for practical steps to improve care should be considered by all aiming to improve outcomes for marginalized populations who may find it difficult to access treatment for HCV.

Abbreviations

| APRI | = | aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index |

| DAA | = | direct-acting antiviral |

| DBST | = | dried blood spot testing |

| HCPs | = | health care professionals |

| HCV | = | hepatitis C virus |

| OAT | = | opioid agonist therapy |

| OST | = | opioid substitution therapy |

| OUD | = | opioid use disorder |

| PCPs | = | primary care physicians |

| TE | = | transient elastography |

| IDU | = | injecting drug users |

| PWID | = | people who inject drugs |

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the editorial contribution of Dr L Li, T Lumley, C Corte, and G Myers. This work was funded by Gilead Sciences. Gilead had no influence on the development, research, or writing of the manuscript.

Disclosure

Dr Carlos Roncero received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag, Ferrer-Brainfarma, Pfizer, Reckitt-Benckiser/Indivior, Lun-dbeck, Otsuka, Servier, Shire, Lilly, GSK, Astra, Gilead, and MSD. Dr Pablo Ryan received honoraria from Merck, Gilead, and ViiV and received a research grant from Merck Sharpe & Dohme (MISP IIS # 54846). Dr Richard Littlewood received consulting fees from Gilead. Dr Juan Ruiz received honoraria from Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Reckitt-Benckiser/Indivior, Lundbeck, and Gilead. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HajarizadehBGrebelyJDoreGJEpidemiology and natural history of HCV infectionNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol201310955356223817321

- RonceroCLittlewoodRVegaPMartinez-RagaJTorrensMChronic hepatitis C and individuals with a history of injecting drugs in Spain: population assessment, challenges for successful treatmentEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201729662963328230562

- EMCDDAWorld Hepatitis Day – Hepatitis C Among Drug Users in EuropeLisbonEMCDDA2016

- LiVChenJhomepage on the InternetThe burden of hepatitis C in the injection drug user population the framework of stigmaJ Glob Health Published 2014. Available from: http://www.ghjournal.org/the-burden-of-hepatitis-c-in-the-injection-drug-user-population/Accessed August 30, 2017

- GrebelyJBruneauJLazarusJVResearch priorities to achieve universal access to hepatitis C prevention, management and direct-acting antiviral treatment among people who inject drugsInt J Drug Policy201747516028683982

- BruggmannPGrebelyJPreventionGJPrevention, treatment and care of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugsInt J Drug Policy201526S1S22S2625245939

- GeddawyAIbrahimYFElbahieNMIbrahimMADirect acting anti-hepatitis C virus drugs: clinical pharmacology and future directionJ Transl Int Med20175181728680834

- DoreGJAlticeFLitwinAHC-EDGE CO-STAR Study GroupElbasvir-grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2016165962563427537841

- GrebelyJSwanTHickmanMInternational Network for Hepatitis in Substance UsersContradictory advice for people who inject drugs in the 2016 EASL recommendations on treatment of Hepatitis CJ Hepatol20176651101110328167323

- ReadPLothianRChronisterKDelivering direct acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C to highly marginalised and current drug injecting populations in a targeted primary health care settingInt J Drug Policy20174720921528587943

- RobaeysGGrebelyJMaussSInternational Network on Hepatitis in Substance UsersRecommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugsClin Infect Dis201357Suppl 2S129S13723884061

- WrightNReimerJSomainiLAre we ready to treat hepatitis C virus in individuals with opioid use disorder: assessment of readiness in European countries on the basis of an expert-generated modelEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201729111206121428914697

- RonceroCVegaPMartinez-RagaJTorrensMChronic Hepatitis C and people with a history of injecting drugs in Spain: population assessment, challenges for effective treatmentAdicciones2017292717328487933

- EuropeWHOBarriers and facilitators to Hepatitis C treatment for peoples who inject drugs: a qualitative study2012 Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/179750/Barriers-and-facilitators-to-hepatitis-C-treatment-for-PWID-A-qualitative-study-June-2012-rev-5.pdf

- KakkoJGedeonCSandellMPrinciples for managing OUD related to chronic pain in the Nordic countries based on a structured assessment of current practiceSubst Abuse Treat Prev Policy2018132229859110

- HagedornHJRettmannNDieperinkEKnottALandonBEA training model for implementing hepatitis prevention services in substance use disorder clinics: a qualitative evaluationJ Gen Intern Med20153081215122125903992

- MarinhoRTCostaAPiresTLIGUE-C InvestigatorsA multidimensional education program at substance dependence treatment centers improves patient knowledge and hepatitis C careBMC Infect Dis201616156527733137

- JessopABBassSBGashatMAl HajiiMForryJCreating and testing usability of an mHealth tool using targeted messages to affect HCV treatment decisions in HCV plus methadone patientsHepatology2017661316A316A Poster 578

- LubegaSAgbimUSurjadiMMahoneyMKhaliliMFormal hepatitis C education enhances HCV care coordination, expedites HCV treatment and improves antiviral responseLiver Int2013337999100723509897

- KianiGShahiRAlimohammadiARaycraftTSinghAConwayBCommunity pop-up clinic: a harm reduction strategy to engage hepatitis C virus infected injection drug usersJ Hepatol2017661S489

- HarrisMRhodesTHepatitis C treatment access and uptake for people who inject drugs: a review mapping the role of social factorsHarm Reduct J201310723651646

- TreloarCRanceJBackmundMUnderstanding barriers to hepatitis C virus care and stigmatization from a social perspectiveClin Infect Dis201357Suppl 2S51S5523884066

- TreloarCRanceJBathNEvaluation of two community-controlled peer support services for assessment and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in opioid substitution treatment clinics: the ETHOS study, AustraliaInt J Drug Policy2015261099299825697089

- KeatsJMicallefMGrebelyJETHOS Study GroupAssessment and delivery of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in an opioid substitution treatment clinic with integrated peer-based support in Newcastle, AustraliaInt J Drug Policy20152610999100626275578

- CrawfordSBathNPeer support models for people with a history of injecting drug use undertaking assessment and treatment for hepatitis C virus infectionClin Infect Dis201357Suppl 2S75S7923884070

- vanTMHeymannGCherepanovVCan dried blood spots be used for diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C virus infection even if they are stored under non-ideal conditions?J Hepatol2017661s496

- TaitJMStephensBPMcIntyrePGEvansMDillonJFDry blood spot testing for hepatitis C in people who injected drugs: reaching the populations other tests cannot reachFrontline Gastroenterol20134425526228839735

- CoatsJTDillonJFThe effect of introducing point-of-care or dried blood spot analysis on the uptake of hepatitis C virus testing in high-risk populations: a systematic review of the literatureInt J Drug Policy201526111050105526118799

- O’SullivanMProjectITTREAT(Integrated Community Based Test -stage-TREAT HCV Service) for People who Inject Drugs: Year 3 ResultsJ Hepatol2017661 Poster abstract 994

- RemyAJBouchkiraHLamarrePMontaboneSHepatitis Mobile Team: a new concept for benefit toward drugs users and precarious people with hepatitis C in FranceHepatology2016641 Abstract 775

- El-GhitanyEMFarghalyAFaragSPerformance of the validated EGCRISC screening tool in chronic hepatitis C infection detection after application in the Egyptian settingJ Hepatol2017661S279S280

- SureyJStoryAMenezesDConneelyJHaywardAEarth study (Phase 1): expanding access to rapid treatment for Hepatitis CHepatology2016642S461S462

- CullenBLHutchinsonSJCameronSOIdentifying former injecting drug users infected with hepatitis C: an evaluation of a general practice-based case-finding interventionJ Public Health (Oxf)2012341142322138489

- GrebelyJRobaeysGBruggmannPInternational Network for Hepatitis in Substance UsersRecommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugsInt J Drug Policy201526101028103826282715

- GrebelyJOserMTaylorLEDoreGJBreaking down the barriers to hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment among individuals with HCV/HIV coinfection: action required at the system, provider, and patient levelsJ Infect Dis2013207Suppl 1S19S2523390301

- MontolaDLCaravanPChungTRFuchsBCNoninvasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis: clinical applications and future directionsCurr Pathobiol Rep20142424525625396099

- PapalucaTJarmanMCraigieAUse of APRI to exclude cirrhosis in correctional services: minimizing need for FibroscanHepatology2017661541A Poster 1012

- MarshallADMicallefMErrattALiver disease knowledge and acceptability of non-invasive liver fibrosis assessment among people who inject drugs in the drug and alcohol setting: the LiveRLife studyInt J Drug Policy2015261098499126256938

- McGinleyJSchofieldJGarthwaiteMSichi-SmithGLavertyLPetersSEHepatitis C therapy delivered within and by a community addiction service: real life data shows SVR rates >90%J Hepatol2017661S512

- BeaulacJCoraceKBalfourLCooperCImproving Hepatitis C treatment engagement: getting at the what and how of patient information needs and preferencesHepatology2017661853A854 Poster 1595

- SulkowskiMWardKFalade-NwuliaORandomized controlled trial of cash incentives or peer mentors to improve HCV linkage and treatment among HIV/HCV coinfected persons who inject drugs: the CHAMPS StudyJ Hepatol2017661S719

- BruggmannPLitwinAHModels of care for the management of hepatitis C virus among people who inject drugs: one size does not fit allClin Infect Dis201357Suppl 2S56S6123884067

- ThorntonKAPriceJCDemingPExpanding HCV treatment access: training primary care providers in the U.S. using the ECHO modelHepatology2017661607A607A Poster 1129

- ScherzNBrunnerNBruggmannPDirect-acting antivirals for hepatitis C in patient in opioid substitution treatment and heroin assisted treatment: real-life dataJ Hepatol2017661S726

- JohnstonLAhmadFStephensBDillonJFThe eradicate-C study-curing people who are actively injecting drugs of hepatitis C: the first step to eliminationJ Hepatol2017661S312

- LlerenaSA program of testing and treat intended to eliminate Hepatitis C in a prison: the JAILFREE-C studyJ Hepatol2016641 Poster 916

- LitwinAAgyemangLAkiyamaMThe PREVAIL study: intensive models of HCV care for people who inject drugsEASL 2017 - Eur Assoc Study Liver2017 (FRI-194). Available from: http://www.viraled.com/modules/info/files/files_5902192734f8d.pdfAccessed December 12, 2018

- LosikoffPGomesLCoonanBTreatment of Hepatitis C infection in an office- based opiate treatment (OBOT) clinicHepatology2017661624A624A Poster 1161

- MartinNKHickmanMHutchinsonSJGoldbergDJVickermanPCombination interventions to prevent HCV transmission among people who inject drugs: modeling the impact of antiviral treatment, needle and syringe programs, and opiate substitution therapyClin Infect Dis201357Suppl 2S39S4523884064

- FilippovychSBurgayOPavlyiukIResults of hepatitis C treatment program among people who inject drugsJ Hepatol2017661S737

- MartinezADDimovaRMarksKMIntegrated internist - addiction medicine - hepatology model for hepatitis C management for individuals on methadone maintenanceJ Viral Hepat2012191475421129131

- ScottJAronsohnAIIrvinRImproving primary care training for the evaluation and therapy of Hepatitis C in the community-based test and cure of Hepatitis C programHepatology2017661311A311A Poster 568

- ChanPPMohsenWWhelanMCProject ECHO in Australia: a novel tele-mentoring service to aid Hepatitis C treatment in difficult to access populationsHepatology2017661317A318 Poster 851

- FragomeliVWeltmanMAddressing viral hepatitis in the opiate substitution setting: an integrated nursing model of careJ Gastroenterol Hepatol201530Suppl 2611

- WadeAJMacdonaldDMDoyleJSThe cascade of care for an Australian community-based Hepatitis C treatment servicePLoS One20151011e014277026562516

- JoshiSGalvinMWinfreyWFremontMShalabyMHigh cure rate of Hepatitis C in a primary care clinic for people who have limited access to specialty careHepatology2017661845A845A Poster 1582

- PapalucaTMcdonaldLCraigieAA state-wide, nurse-led model of care for HCV in the prison: high SVR12 rates that are equivalent to the specialist liver clinicHepatology2017661609A609A Poster 1132

- DavidCDavidDEssexWDemingPQuallsCRMeraJHepatitis C treatment outcomes in a pharmacist-managed clinic in a rural tribal health systemHepatology2017661331A331A Poster 609

- FruehaufHKnoblochNKnoblochSSemelaDVavrickaSRThe “HCV Advisor” App – A web-based mobile application to identify suitable treatments with direct antiviral agents for chronic hepatitis C infectionJ Hepatol2017661S507

- TalalAHAndrewsPMcleodATelemedicine-based Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) management for individuals on opioid agonist treatment (OAT)Hepatology2017631475A

- MasonKDoddZGuytonMUnderstanding real-world adherence in the directly acting antiviral era: a prospective evaluation of adherence among people with a history of drug use at a community-based program in Toronto, CanadaInt J Drug Policy20174720220828619394

- OevrehusALHKrarupHBirkemoseIMössnerBChristensenPBFour weeks of Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir + Ribavirin with or without interferon gives very high and sustained cure rates in difficult to reach but easy to treat injecting drug users with chronic hepatitis C: final results of the 4WIDUC studyJ Hepatol2017661S287

- ToppLDayCAWandHHepatitis Acceptability and Vaccine Incentives Trial (HAVIT) Study GroupA randomised controlled trial of financial incentives to increase hepatitis B vaccination completion among people who inject drugs in AustraliaPrev Med201357429730323639625

- MaticicMVidecnik ZormanJGregorcicSSchatzELazarusJVAre there national strategies, plans and guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis C in people who inject drugs? A survey of 33 European countriesBMC Infect Dis201414Suppl 6S1425252635

- AlimohammadiASinghAShahi1 R, Raycraft T, Kiani G, Conway B. HCV-infected people who inject drugs (PWID): engagement in care and treatment, and prevention of reinfectionJ Hepatol2017661S273

- GountasIGamkrelidzeIPasiniKHCV elimination among people who inject drugs. What would happen after the WHO HCV elimination target is achieved?J Hepatol2017661S405S406

- European Association for the Study of the LiverEASL recommendations on treatment of Hepatitis CJ Hepatol201766115319427667367

- European Association for Study of liverEASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infectionJ Hepatol201460239242024331294

- GradyBPSchinkelJThomas XvDOHepatitis C virus reinfection following treatment among people who use drugsClin Infect Dis2013Suppl 2S105S11023884057

- ChungRTDavisGLJensenDMHepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with Hepatitis C VirusHepatology201562393295426111063

- StrathdeeSALatkaMCampbellJFactors associated with interest in initiating treatment for hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection among young HCV-infected injection drug usersClin Infect Dis200540Suppl 5S304S31215768339

- HarrisMRhodesTMartinATaming systems to create enabling environments for HCV treatment: negotiating trust in the drug and alcohol settingSoc Sci Med201383192623465200

- IrvingWLHarrisonGIHickmanMHepatitis C: awareness Through to Treatment (HepCATT) study: evaluation of an intervention designed to increase diagnosis and treatment of patients with hepatitis C virus infection in drug treatment settingsJ Hepatol2017661S712S713

- GrebelyJBruggmannPBackmundMDoreGJMoving the agenda forward: the prevention and management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugsClin Infect Dis201357Suppl.2S29S3123884062

- GradyBPSchinkelJThomasXVDalgardOHepatitis C virus reinfection following treatment among people who use drugsClin Infect Dis201357Suppl.2S105S11023884057

- HelsperCWvan EssenGABontenMJde WitNJA support programme for primary care leads to substantial improvements in the effectiveness of a public hepatitis C campaignFam Pract201027332833220223833

- HashimAO’SullivanMWilliamsHVermaSDeveloping a community HCV service: project ITTREAT (integrated community-based test - stage - TREAT) service for people who inject drugsPrim Health Care Res Dev201819211012029199921

- HagedornHDieperinkEDingmannDIntegrating hepatitis prevention services into a substance use disorder clinicJ Subst Abuse Treat200732439139817481462