Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the most common chronic bloodborne infection in the United States, with approximately 3.2 million Americans being chronically infected. Rates of HCV-related end-stage liver disease and its associated morbidity and mortality have yet to peak, so there is a pressing need for more effective and tolerable HCV treatment. HCV genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6 are considered difficult to treat, and the need for improved therapies is especially great for persons infected with these genotypes.

Current strategies for HCV treatment

Current therapy for genotype 1 HCV infection includes triple therapy with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and a NS3/4A protease inhibitor. Sustained virologic response (SVR) rates with triple therapy range from 42% to 75%, a vast improvement over pegylated interferon and ribavirin therapy alone. However, response rates remain suboptimal, and triple therapy is associated with significant adverse effects and is only indicated for genotype 1 HCV infection.

Novel drugs for HCV treatment

HCV drug development is proceeding at a rapid pace to meet this need. Novel direct acting antiviral agents in several classes, including new NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors, NS5A replication complex inhibitors, NS5B polymerase inhibitors, interferon lambda, and microRNAs, are in varying stages of development. These new therapeutic agents promise SVR rates of up to 100% with durations as short as 12 weeks and, often, fewer adverse effects.

Conclusion

New drug development in HCV is proceeding at an unprecedented pace. Novel agents promise higher SVR rates, shorter duration of therapy, and fewer adverse effects than have been possible with HCV therapy to date.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the most common chronic bloodborne infection in the United States, with approximately 3.2 million Americans chronically infected.Citation1 Moreover, this number is likely an underestimate, as groups with a high prevalence of HCV (incarcerated and homeless persons) are not reflected in these data.Citation1 Worldwide, an estimated 180 million persons have chronic HCV infection.Citation2 Infection with hepatitis C is a leading cause of death from liver disease and the most common indication for liver transplant in the United States.Citation3

HCV is most efficiently transmitted through large or repeated percutaneous exposure to infected blood. Therefore, use of contaminated needles for injection drug use is currently the most common method of HCV transmission in the United States.Citation1 Although much less frequent, occupational, perinatal, health care, and sexual exposures can result in the transmission of HCV.Citation4–Citation7 Since the implementation of routine blood donor screening in 1992, transmission of HCV via blood products is now extremely rare in the developed world.

Six major HCV genotypes (named 1–6) are known to exist with variable geographic distribution. Genotype 1 (including subtypes 1a and 1b) is the most common in the United States and worldwide, accounting for 60% of global infections, followed by genotypes 2 and 3.Citation2 Genotypes 4–6 are less common in the United States but occur frequently in other countries. Genotype 4 is seen most frequently in Egypt, the Middle East, and Central Africa. Genotype 5 is found in South Africa, and genotype 6 is found in Asia.Citation2

HCV genotypes play an important role in hepatitis C treatment evaluation, as genotypes can be classified as more or less responsive to antiviral therapy with pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin (PR). Genotypes 1 and 4 are less responsive to PR, and genotypes 2 and 3 are more responsive. With the advent of protease inhibitor-based hepatitis C therapy in 2011, HCV genotype determination has become especially important, as HCV protease inhibitors are only indicated for genotype 1 HCV infection.Citation8

In addition to genotyping, the recently described IL28B polymorphism is also important in predicting treatment success. A genome-wide association study published in 2012 found that a single nucleotide polymorphism at the IL28B location is associated with the likelihood of response to hepatitis C treatment.Citation9 Persons with the CC allele have the highest chance of sustained virologic response (SVR) or cure, those with CT have intermediate response, and those with TT allele have the lowest SVR rates.Citation9 This discovery offers some explanation as to the relatively low response rates of African Americans to hepatitis C treatment compared with those patients of European ancestry. Analysis of worldwide distribution of IL28B polymorphisms show that the TT allele is most prevalent in persons of African descent, whereas the CC allele is most common in persons of European descent.Citation9

In contrast to hepatitis A and B infections, most acute HCV infections are asymptomatic, with less than 20% of persons developing jaundice. Chronic HCV infection develops in 70%–85% of HCV-exposed persons.Citation10 Even once chronic, the majority of HCV-infected individuals remain asymptomatic. Thus, hepatitis C has been referred to as the “silent killer,” as most infected persons develop progressive liver fibrosis over years without developing any symptoms. When symptoms of chronic hepatitis C develop, they are often nonspecific, including fatigue, abdominal pain, depression, and joint pain. Extrahepatic manifestations, such as glomerulonephritis, mixed cryoglobulinemia, vasculitis, and neuropathy, are also possible.Citation11

Because of the asymptomatic nature of acute and chronic infection and the suboptimal application of risk factor-based screening for HCV infection, the majority of HCV-infected persons (50%–85%) are unaware of their infection.Citation12 In an effort to increase the number of persons aware of their HCV infection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently revised their recommendation for HCV screening, now recommending that all persons born between 1945 and 1965 receive a one-time HCV antibody test.Citation12 This is in addition to the previous recommendation that persons in high-risk groups, such as injection drug users (past or present); those who received blood products or organ transplants before 1992; those with HIV, a history of hemodialysis, or elevated alanine transaminase levels; children born to HCV-infected mothers; and health care workers with recognized exposures be screened for HCV infection.Citation13

The goal of enhanced screening is to make more HCV-infected persons aware of their infection so they can get needed care and evaluation for treatment. On the basis of prediction models, rates of cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease resulting from HCV infection are expected to continue to rise until they peak in 2030, with 45% of those with hepatitis C having cirrhosis compared with 25% in 2010.Citation14 One way to positively affect these numbers is to get more infected persons diagnosed and treated, so that our current efficacious hepatitis C treatment can achieve effectiveness.

In this review, we first outline current therapeutic strategies for difficult-to-treat HCV genotypes. We then describe the wide range of novel drugs in development for HCV treatment that are likely to become the new standard of care treatment in the near future.

Overview of current therapeutic strategies

Hepatitis C is treatable and curable. Historically, treatment success rates have been low, and treatment regimens have been associated with significant adverse effects. From 2001 through 2011, the standard-of-care therapy for hepatitis C consisted of PR, with duration of therapy ranging from 24 weeks for genotypes 2 and 3 (with 70%–80% SVR rates) to 48 weeks for genotype 1 (with 40%–50% SVR rates).Citation15 This regimen was associated with a variety of adverse effects, including influenza-like symptoms, depression, rash, and cytopenias. In 2011, treatment was greatly advanced with the introduction of two novel HCV NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors: telaprevir and boceprevir. Telaprevir and boceprevir were the first direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) directly targeting HCV to be introduced. Therapy combining either telaprevir or boceprevir in a “triple-therapy” regimen that includes pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin has become the current standard-of-care treatment for genotype 1 HCV infection.Citation8 For all other genotypes, standard-of-care therapy remains pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin alone.

Mechanism of action of NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors

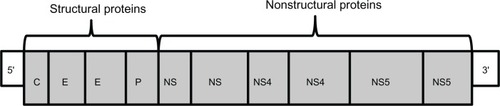

During the HCV viral lifecycle, the HCV viral genome is translated by host ribosomes into a viral polypeptide approximately 3,000 amino acids in length. This polypeptide is subsequently cleaved by viral protease NS3/4A into nonstructural proteins, including NS5A and NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (). These nonstructural proteins form the viral replication complex that is required for HCV viral propagation. Drugs in the protease inhibitor (PI) class inhibit HCV propagation by binding to the catalytic site of the NS3/4A protease enzyme.

Figure 1 Hepatitis C viral genome, a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome, with 5′ and 3′ ends with genes that encode structural proteins and nonstructural proteins.

The PI class inhibits viral replication at an early stage and is a highly potent class of drugs. However, this class has a much lower barrier to resistance (especially in genotype 1a), and cross-drug resistance can occur (). Genotype 1a virus requires only a single mutation (the amino acid mutation R155 K) to generate PI resistance, whereas genotype 1b virus requires two mutations.Citation16,Citation17 Resistance is an important new aspect of HCV therapy with PIs (and other novel DAAs), as resistance was not a feature of PR therapy.

Table 1 Comparison of pharmacologic mechanism of action, potency, resistance profile, genotype activity, and examples of direct acting hepatitis C antiviral drugs, by drug class

Telaprevir-based triple therapy

The efficacy and safety of telaprevir were evaluated in two major phase III trials for chronic genotype 1 HCV infection: one for treatment-naïve patients (ADVANCE), and the other for treatment-experienced patients (REALIZE).Citation18,Citation19 In the ADVANCE trial, patients were treated with 12 weeks of telaprevir plus PR, followed by an additional 12 weeks of PR for those with favorable early virologic response (“response-guided therapy”), or an additional 36 weeks of PR for those without a favorable early virologic response. Those in the telaprevir group had a 75% SVR rate compared with a 44% SVR rate for the PR control group. Fifty-eight percent of patients were eligible for response-guided therapy (demonstrating undetectable HCV RNA at 4 and 12 weeks of therapy) and thus were able to complete all treatment at 24 weeks. Adverse effects of anemia, gastrointestinal adverse effects, and rash occurred more commonly in the telaprevir group compared with the PR group. However, rates of discontinuation were similar, at 10% for the telaprevir group and 7% in the PR group.Citation18

In the REALIZE trial, patients were divided by prior treatment response into null responders, partial responders, and relapsers. Prior null responders who were treated with telaprevir plus PR for 12 weeks followed by PR for 36 weeks had a 29% SVR rate (compared with 5% for PR); partial responders had a 59% SVR (compared with 15% for PR); and prior relapsers had an 83% SVR rate (compared with 24% for PR). Again, adverse effects including anemia, anorectal symptoms, and skin rashes were more common in the telaprevir group than the PR group.Citation19

Boceprevir-based triple therapy

The efficacy and safety of boceprevir was evaluated in two major phase III trials: one for treatment-naïve patients (SPRINT-2) and the other for treatment-experienced patients (RESPOND-2).Citation20,Citation21 In the SPRINT-2 trial, patients received a 4-week lead-in period of PR treatment followed by 24 weeks of boceprevir plus PR if HCV RNA was undetectable at weeks 8 and 24 (response-guided therapy), or 24 weeks of boceprevir plus PR plus an additional 20 weeks of PR if HCV RNA was detectable at either week 8 or 24. In SPRINT-2, black and nonblack cohorts were analyzed separately. A total of 67% of nonblack patients achieved SVR compared with 40% of PR-treated controls. A total of 42% of black patients achieved SVR compared with 23% of PR-treated controls. Forty-four percent of patients qualified for response-guided therapy in this trial. The main adverse effects reported were anemia and dysgeusia.Citation20

In RESPOND-2, boceprevir was added to PR therapy in patients who did not have an SVR to prior PR therapy. This trial enrolled patients who were partial responders and relapsers to PR, but did not enroll prior null responders. Again, a 4-week PR lead-in was used, followed by boceprevir plus PR for 32 weeks, plus an additional 12 weeks of PR if HCV RNA was detectable at 8 weeks. A second arm used boceprevir plus PR for an additional 44 weeks after lead-in. Overall SVR rates were 59% in the first group and 66% in the second group, compared with 21% in the PR control group. Anemia, dysgeusia, rash, and dry skin were reported more commonly in the boceprevir groups than the control group.Citation21

The advent of NS3/4A protease inhibitor-based triple therapy for HCV infection has ushered in a new era for hepatitis C treatment. SVR rates are higher and treatment durations potentially shorter than they have ever been for genotype 1 HCV infection. However, there remain several drawbacks to PI-based therapy. First, PIs are only approved for genotype 1 HCV infection, leaving many thousands of non-genotype 1 patients awaiting more effective therapies. In addition, unlike PR therapy, PI-based therapy is associated with the development of HCV resistance. For this reason, patients who fail treatment with boceprevir or telaprevir cannot be re-treated with the same or the other PI,Citation8 leaving no re-treatment option for this group. Another drawback is the additional, often severe, adverse effects associated with PI therapy, most significantly the anemia associated with both telaprevir and boceprevir therapy. Finally, the cost and complexity of this therapy make it unavailable to many HCV-infected patients.

DAAs under development

Fortunately, new drug development for HCV infection has skyrocketed since the release of boceprevir and telaprevir, and an unprecedented number of new DAAs are in various stages of development (). These new DAAs have significant promise to further advance the field of hepatitis C treatment with higher SVR rates, shorter durations of therapy, fewer adverse events, and efficacy against HCV genotypes other than genotype 1.

Table 2 Genotype activity, dosing schedule, clinical trial name and population studied, SVR, and adverse events noted in the novel, direct-acting antivirals, by drug class

This section discusses drug class, mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, potency, efficacy, and tolerability of select HCV DAAs under development, and highlights some specific examples within each class. Of note, when reporting efficacy, most trials use a new SVR definition (SVR12), defined as maintenance of undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after completion of treatment (as opposed to the standard 24 weeks).

Novel NS3/4A serine protease inhibitors

Simeprevir (formerly TMC-435; Janssen Research and Development, Raritan, NJ, USA) is a macrocyclic NS3/4A PI that has activity against HCV genotypes 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 but is not active against genotype 3 (). Simeprevir, metabolized by the CYP3A enzyme, has a half-life of 40 hours, which allows for once-daily dosing.Citation22 QUEST-2, a Phase III clinical trial, assessed simeprevir 150 mg daily plus PR for 12 weeks, followed by PR alone for either 12 or 36 weeks (response-guided therapy) in treatment-naïve, genotype 1 HCV infection.Citation23 For those in the simeprevir group, 81% achieved SVR12; response rates were higher in those with IL28B polymorphism CC (96% SVR12) and in those with lower-stage (METAVIR 0 to 2) liver fibrosis (SVR12 85%). The adverse effects that occurred more frequently in patients receiving simeprevir were rash (23% versus 11%) and indirect hyperbilirubinemia. A summary of the Phase II clinical trials of simeprevir has been published.Citation22 A new drug application was submitted on behalf of simeprevir to the US Food and Drug Administration on March 28, 2013.Citation24

Faldaprevir (formerly BI 201335) is a potent PI that is dosed once daily (). In the Efficacy and Safety of BI 201335 (Faldaprevir) in Combination With pegylated Interferon-alpha and Ribavirin in Treatment-naïve Genotype 1 Hepatitis C Infected Patients (STARTVerso) study, genotype 1, treatment-naïve patients were given either 120 mg or 240 mg faldaprevir with PR for 12 weeks.Citation25 Overall, around 80% achieved SVR12, with higher responses seen in those with genotype 1b and the CC genotype of the IL28B polymorphism. Adverse events that caused treatment discontinuation, including indirect hyperbilirubinemia, occurred in 5% of patients who received faldaprevir 240 mg. In the SILEN-C2 trial, genotype 1 patients with prior nonresponse to therapy were given faldaprevir and PR and 21–50% achieved SVR.Citation26 Faldaprevir has also been combined with BI 207127 and ribavirin in a small, interferon-free trial of treatment-naïve, genotype 1 patients that found that 73%–94% of the patients had undetectable HCV RNA levels at 4 weeks.Citation27

Danoprevir (formerly RG7227; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) is a potent, macrocyclic PI with activity against HCV genotypes 1, 4, and 6, which has been studied in coadministration with ritonavir (). Similar to the HIV protease inhibitor drugs, it has been shown that combining danoprevir with 100 mg of ritonavir daily improves both the pharmacokinetics and safety profile of danoprevir. In the DAUPHINE Phase IIb clinical trial of genotype 1/4, treatment-naïve, noncirrhotic adults, danoprevir was combined with ritonavir plus PR for 12 weeks or 24 weeks (response-guided therapy), resulting in SVR12 rates of 77% and 86%.Citation28 ABT-450 is another PI that has been combined with ritonavir to enhance its pharmacokinetics profile.

Asunaprevir (formerly BMS-650032) is a highly active PI that has been studied in combination with a potent NS5A replication complex inhibitor in interferon-free trials of noncirrhotic, prior null responders, with genotype 1 chronic HCV infection (). Diarrhea and headaches were the most common adverse events in these trials.Citation29,Citation30

Other PI drugs under development include narlaprevir (SCH 900518) and vaniprevir (MK-7009).

NS5A replication complex inhibitors

The exact function of the NS5A protein is unknown, but it is a protein with pleiotropic functions and is important in HCV replication (). Daclatasvir (formerly BMS-790052; Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA) is a NS5A replication complex inhibitor that is dosed daily and potently inhibits HCV replication across all genotypes. It works by inhibiting the formation of a functional viral replication complex by binding to the N-terminus of the nonenzymatic NS5A protein. Its efficacy has been demonstrated in combination with PR in genotype 1, treatment-naïve, noncirrhotic patientsCitation31 and in interferon-free trials ().Citation29,Citation32 Daclatasvir was combined with asunaprevir and a nonnucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitor (BMS-791325) in treatment-naïve, genotype 1, noncirrhotic patients for 12 and 24 weeks, and 88% and 94% achieved SVR, respectively.Citation33 The most frequently reported adverse effects were headache, weakness, diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain. No serious changes in liver enzymes (alanine transaminase or aspartate transaminase), bilirubin, or blood cell counts were observed. Daclatasvir was used successfully in combination with sofosbuvir (see NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor section below) in a liver transplant patient with severe recurrent cholestatic HCV infection and in combination with PR in another liver transplant patient.Citation34,Citation35 Caution is warranted, however, when combining daclatasvir with NS5B inhibitors, given the death of one patient and severe cardiotoxicity in other patients in a study of daclatasvir and BMS-986094.Citation36 Other drugs in this class under development include ABT-267 and ledipasvir.

NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors

Nucleoside/nucleotide inhibitors (NIs) act as chain terminators blocking the nascent HCV RNA elongation by HCV polymerase (). The structure and function of the catalytic site of the polymerase is highly conserved among HCV genotypes. Therefore, the NIs as a class should have activity against all genotypes. In addition, the NIs have the highest barrier to resistance (because a mutation in the polymerase active site results in a major loss in viral fitness). Nonnucleoside inhibitors bind to polymerase away from the catalytic site (). Although potentially potent, this class has a low barrier to resistance, and preliminary studies have demonstrated high rates of viral breakthrough and relapse.Citation37

Sofosbuvir (formerly GS7977; Gilead, Foster City, CA, USA) is a uridine analogue in the NI class that is dosed once daily and has demonstrated clinical efficacy against genotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (). GS-7977 With Peginterferon Alfa 2a and Ribavirin for 12 Weeks in Treatment-Naïve Subjects With Chronic Genotype 1, 4, 5, or 6 HCV Infection (NEUTRINO), a Phase III clinical trial of treatment-naïve (17% with cirrhosis) genotype 1 (89%), 4 (9%), and 5/6 (2%) patients treated with sofosbuvir plus PR for 12 weeks found SVR12 rates of 90% (92% for genotype 1a, 82% for genotype 1b, 96% for genotype 4, 100% for genotype 5/6).Citation38 Very few (2%) patients in NEUTRINO discontinued treatment because of adverse events. The Phase III Study of PSI-7977 and Ribavirin (FISSION) trial assessed the efficacy of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 12 weeks in genotype 2 or 3 treatment-naïve (20% with cirrhosis) patients and found it was noninferior to standard-of-care PR therapy, with SVR12 rates of 67% in both groups. In those with genotype 2, 97% achieved an SVR12 compared with 56% in those with genotype 3.Citation38 GS-7977 + Ribavirin for 12 Weeks in Subjects With Chronic Genotype 2 or 3 HCV Infection Who Are Interferon Intolerant, Interferon Ineligible or Unwilling to Take Interferon (POSITRON) enrolled treatment-naïve genotype 2 or 3 patients for whom interferon therapy was not an option (contraindication, unacceptable adverse effects) and found a 78% SVR12 in patients treated with 12 weeks of sofosbuvir and ribavirin.Citation39 The GS-7977 + Ribavirin for 12 or 16 Weeks in Treatment Experienced Subjects With Chronic Genotype 2 or 3 HCV Infection (FUSION) study enrolled genotype 2 or 3 patients who had not responded to prior interferon therapy (34% had cirrhosis).Citation39 Among those treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin for 12 weeks, 50% achieved SVR12, and in those treated for 16 weeks, 73% had an SVR12. The most common adverse events in all Phase III sofosbuvir trials were fatigue, headache, nausea, and insomnia. The only known sofosbuvir resistance variant (S282T mutation) was not detected on deep-sequencing assays in any patient who received sofosbuvir in these studies.Citation38,Citation39

Another NI under development is mericitabine (formerly R7128; Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland), a cytidine analogue with activity against genotypes 1, 2, and 3 ().

Other therapeutic options under exploration/host targets

Pegylated interferon lambda is a type 3 interferon that has been shown to inhibit HCV viral replication in vitro. However, unlike interferon alpha, lambda has a more restricted cell and tissue distribution. Lambda is expressed by hepatocytes but is minimally expressed by the cells of hematopoietic lineage. In proof-of-concept trials, pegylated interferon lambda is much better tolerated without the influenza-like symptoms, musculoskeletal complaints, and neutropenia often experienced by patients receiving type 1 interferon alpha. Efficacy and Safety Study of PEG-rIL-29 Plus Ribavirin to Treat Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection (EMERGE), a Phase II clinical trial, compared lambda with alpha interferon in genotype 2 and 3 patients and found similar SVR rates but fewer interferon-related adverse events.Citation40 Despite promising early results from interferon-free trials, difficult-to-treat patients will likely need interferon, and having a better tolerated interferon option will be critical.

MicroRNAs are small (~22 nucleotides) RNAs that interact with messenger RNA and reduce translated protein, regulating host gene expression at the posttranscriptional level. miR-122 is a liver-specific microRNA required for the stability and propagation of HCV RNA.Citation17 The miR-122 binding sites are conserved across all HCV genotypes.Citation41 Miravirsen (Santaris Pharma, Hørsholm, Denmark) is an antagomir to miR-122 that has been shown to have significant anti-HCV viral activity in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending multiple dose-ranging Phase IIa study.Citation41 Miravirsen was given subcutaneously in weekly doses during a 29-day period (at doses of 3 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, or 7 mg/kg) and resulted in at least a 2 log10 reduction in HCV RNA in six of nine patients in the 5 mg/kg and 7 mg/kg groups. The use of miravirsen alone resulted in undetectable HCV RNA levels in five patients, but viral rebound occurred in all but one. One patient had a syncopal episode after a miravirsen injection, and some patients had injection site reactions. Miravirsen, a host-targeting agent, could potentially complement the direct acting antiviral agents in the treatment of chronic HCV infection, but more research is needed.

Conclusion

Hepatitis C continues to be an emerging public health threat, and morbidity and mortality from hepatitis C-related liver disease have yet to peak in the United States. There is, however, opportunity for positively affecting these projections by both diagnosing more persons who are unaware of their HCV infection and treating with antiviral therapy those who are known to be infected. Although current standard-of-care antiviral therapy with pegylated interferon, ribavirin, and a protease inhibitor is efficacious for genotype 1 HCV, this therapy has many drawbacks, including complicated dosing regimens, a long duration of therapy, multiple and potentially serious adverse effects, and approval for genotype 1 HCV infection only.

This review outlines many promising new DAAs in development that offer superior efficacy, improved tolerability, and shorter duration of therapy. Many show pan-genotypic activity, so that patients with difficult-to-treat non-1 genotypes will also be eligible for treatment with these new agents. In addition, interferon-free regimens, which have long been the Holy Grail of hepatitis C treatment, are now within reach. We are entering an exciting new era of hepatitis C treatment that promises an improved hepatitis C treatment experience and outcome both for the patient and the provider.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ArmstrongGLWasleyASimardEPMcQuillanGMKuhnertWLAlterMJThe prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002Ann Intern Med20061441070571416702586

- Global Alert and Response (GAR): hepatitis C: HCV genotypes [webpage on the Internet]Geneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/whocdscsrlyo2003/en/index2.html#HCVAccessed May 13, 2013

- KimWRThe burden of hepatitis C in the United StatesHepatology2002365 Suppl 1S30S3412407574

- TomkinsSEElfordJNicholsTOccupational transmission of hepatitis C in healthcare workers and factors associated with seroconversion: UK surveillance dataJournal of Viral Hepatitis20121919920422329374

- CottrellEBChouRWassonNRahmanBGuiseJMReducing Risk for Mother-to-Infant Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med2013158210911323437438

- ThompsonNDPerzJFMoormanACHolmbergSDNonhospital health care-associated hepatitis B and C virus transmission: United States, 1998–2008Ann Intern Med2009150333919124818

- WittMDSeabergECDarilayAIncident hepatitis C virus infection in men who have sex with men: a prospective cohort analysis, 1984–2011Clin Infect Dis2013571778423532480

- GhanyMGNelsonDRStraderDBThomasDLSeeffLBAmerican Association for Study of Liver DiseasesAn update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver DiseasesHepatology20115441433144421898493

- GeDFellayJThompsonAJGenetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearanceNature2009461726239940119684573

- AlterMJMargolisHSKrawczynskiKThe natural history of community-acquired hepatitis C in the United States. The Sentinel Counties Chronic non-A, non-B Hepatitis Study TeamN Engl J Med31199232727189919051280771

- HoofnagleJHCourse and outcome of hepatitis CHepatology2002365 Suppl 1S21S2912407573

- SmithBDMorganRLBeckettGACenters for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965MMWR Recomm Rep17201261RR-413222895429

- Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Centers for Disease Control and PreventionMMWR Recomm Rep199847RR-19139

- DavisGLAlterMJEl-SeragHPoynardTJenningsLWAging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progressionGastroenterology2010138251352119861128

- GhanyMGStraderDBThomasDLSeeffLBAmerican Association for the Study of Liver DiseasesDiagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an updateHepatology20094941335137419330875

- McPheeFFriborgJLevineSResistance analysis of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease inhibitor asunaprevirAntimicrob Agents Chemother20125673670368122508297

- SchaeferEAChungRTAnti-hepatitis C virus drugs in developmentGastroenterology201214261340135022537441

- JacobsonIMMcHutchisonJGDusheikoGADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infectionN Engl J Med232011364252405241621696307

- ZeuzemSAndreonePPolSREALIZE Study TeamTelaprevir for retreatment of HCV infectionN Engl J Med232011364252417242821696308

- PoordadFMcConeJJrBaconBRSPRINT-2 Investigators. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2011364131195120621449783

- BaconBRGordonSCLawitzEHCV RESPOND-2 Investigators. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infectionN Engl J Med2011364131207121721449784

- TanwarSTremblingPMDusheikoGMTMC435 for the treatment of chronic hepatitis CExpert Opin Investig Drugs201221811931209

- MannsPMPoordadFSimeprevir (TMC435) with peginterferon/ribavirin for treatment of chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in treatment-naive patients: results from QUEST-2 a phase III trialPresented at: 48th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the LiverApril 24–28; 2013Amsterdam

- Janssen Research and Development, LLCJanssen submits new drug application to US FDA for simeprevir (TMC435) for combination treatment of adult patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C [press release]Raritan, NJJanssen Research and Development, LLC3282013 Available from: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/janssen-submits-new-drug-application-to-us-fda-for-simeprevir-tmc435-for-combination-treatment-of-adult-patients-with-genotype-1-chronic-hepatitis-c-200501671.htmlAccessed May 13, 2013

- FerenciPAsselahTFosterGRFaldaprevir plus pegylated interferon alfa-2A and ribavirin in chronic HCV genotype-1 treatment-naive patients: final results from STARTVerso1, a randomised double blind placebo-controlled phase III trialPresented at: 48th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the LiverApril 24–28; 2013Amsterdam

- SulkowskiMSBourlièreMBronowickiJPFaldaprevir combined with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C virus genotype-1 patients with prior nonresponse: SILEN-C2 trialHepatology20135762155216323504636

- ZeuzemSAsselahTAngusPFaldaprevir (BI 201335), BI 207127 and ribavirin oral therapy for treatment-naive HCV genotype 1: SOUND-C1 final resultsAntivir Ther Epub442013

- EversonGCooperCHézodeCRapid and sustained achievement of undetectable HCV RNA during treatment with ritonavir-boosted danoprevir/peg-IFNa-2a/RBV in HCV genotype 1 or 4 patients: DAUPHINE week 12 interim analysisPaper presented at: 47th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the LiverApril 18–22; 2012Barcelona

- LokASGardinerDFLawitzEPreliminary study of two antiviral agents for hepatitis C genotype 1N Engl J Med2012366321622422256805

- ChayamaKTakahashiSToyotaJDual therapy with the nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor, daclatasvir, and the nonstructural protein 3 protease inhibitor, asunaprevir, in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected null respondersHepatology201255374274821987462

- PolSGhalibRHRustgiVKDaclatasvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C genotype-1 infection: a randomised, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, phase 2a trialLancet Infect Dis201212967167722714001

- SuzukiYIkedaKSuzukiFDual oral therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for patients with HCV genotype 1b infection and limited treatment optionsJournal of hepatology201223120088100881

- EversonGTSimsKDRodriguez-TorresMInterim analysis of an interferon (IFN)- and ribavirin (RBV)-free regimen of daclatasvir (DCV), asunaprevir (ASV), and BMS-791325 in treatment-naive, hepatitis C virus genotype 1-infected patientsPaper presented at: 48th Annual Meeting of the European Association for the Study of the LiverApril 24–28; 2013Amsterdam

- FontanaRJHughesEAAppelmanHHindesRDimitrovaDBifanoMCase report of successful peginterferon, ribavirin, and daclatasvir therapy for recurrent cholestatic hepatitis C after liver retransplantationLiver Transpl20121891053105922706796

- FontanaRJHughesEABifanoMSofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination therapy in a liver transplant recipient with severe recurrent cholestatic hepatitis CAm J Transplant20131361601160523593993

- SheridanCCalamitous HCV trial casts shadow over nucleoside drugsNat Biotechnol201230111015101623138280

- SorianoVVispoEde MendozaCHepatitis C therapy with HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitorsExpert Opin Pharmacother20131491161117023621117

- LawitzEMangiaAWylesDSofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infectionN Engl J Med2013368201878188723607594

- JacobsonIMGordonSCKowdleyKVPOSITRON StudyFUSION StudySofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment optionsN Engl J Med2013368201867187723607593

- MuirAEMERGE Study GroupHillsonJGrayTPeginterferon lambda-1a (Lambda) compared to peginterferon alfa-2a (Alfa) in treatment-naïve patients with HCV genotypes (GT) 1 or 4: SVR24 results from EMERGE Phase 2bPresented at: 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver DiseasesNovember 9–12; 2012Boston, MA

- JanssenHLReesinkHWLawitzEJTreatment of HCV infection by targeting microRNAN Engl J Med2013368181685169423534542