Abstract

Over recent years, many environmental pollutant chemicals have been shown to possess the ability to interfere in the functioning of the endocrine system and have been termed endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). These compounds exist in air as volatile or semi-volatile compounds in the gas phase or attached to particulate matter. They include components of plastics (phthalates, bisphenol A), components of consumer goods (parabens, triclosan, alkylphenols, fragrance compounds, organobromine flame retardants, fluorosurfactants), industrial chemicals (polychlorinated biphenyls), products of combustion (polychlorinated dibenzodioxins/furans, polyaromatic hydrocarbons), pesticides, herbicides, and some metals. This review summarizes current knowledge concerning the sources of EDCs in air, measurements of levels of EDCs in air, and the potential for adverse effects of EDCs in air on human endocrine health.

Introduction

All terrestrial animals with lungs are dependent on the supply of oxygen from air, and pollution of air can result in the inadvertent intake of many undesired components with adverse consequences. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), air pollution caused the death of 6.5 million people worldwide in 2012.Citation1 Of this global mortality, about 3 million deaths were caused by outdoor air pollution, but this varied markedly according to geographic location, with the highest values recorded in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (238.4 deaths per 100,000 population) and the lowest values recorded in Brunei Darussalam and in Australia/Sweden (0.2 and 0.4 per 100,000 population, respectively).Citation1 However, WHO has attributed an even greater number of deaths to indoor air pollution, and, in 2012, they estimated this to be about 4 million people globally, largely resulting from heating and cooking with solid fuels in an indoor environment without adequate ventilation.Citation2

Pollutants may be natural or man-made, and they may occur as gases, liquid droplets, or solid particles as summarized in . Gaseous components of air pollution include carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, ammonia, and ground-level ozone.Citation1–Citation3 Particulate matter (PM) includes dust, soil, acids, organic molecules, and some metals.Citation4 It is categorized according to the size of the particles, with particles of diameter 2.5–10 µm considered coarse (PM10), <2.5 µm fine (PM2.5), and <0.1 µm ultrafine (PM0.1).Citation4 Distributed between the gaseous and particulate phases are also a range of organic pollutant molecules which may exist as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) in gaseous form or which may attach to PM. Some of these compounds are now known to have profound effects on the functioning of the endocrine system and have been termed endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs).Citation5 Whilst much has been written over the past two decades of the actions of EDCs from oral and dermal exposure, research is increasingly documenting their presence in air which opens a debate on the potential for adverse consequences from inhalation of EDCs. This review aims to summarize current knowledge concerning the sources of EDCs in air, measurements of levels of the EDCs in outdoor versus indoor air, and the potential for adverse effects on human endocrine health.

Table 1 Origins of air pollution from natural sources and from human activities

What are EDCs?

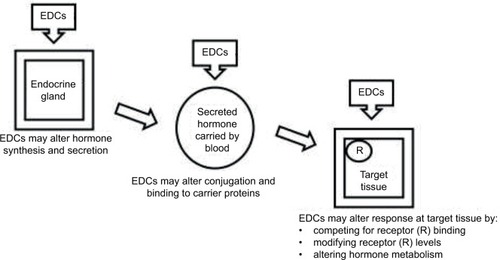

An EDC is defined as “an exogenous substance that causes adverse health effects in an intact organism, and/or its progeny, consequent to changes in endocrine function.”Citation6 Normal function of the endocrine system is dependent on hormones which act as chemical messengers to regulate physiological functions. Hormones are secreted by glands distributed around the body and are carried by the blood (as conjugates and/or bound to carrier proteins) to act on target cells of distant organs. At the target cells, the hormones act through binding to specific cellular receptors which then relay signals into the cell. Intracellular signaling may involve genomic and/or non-genomic mechanisms.Citation5 By the genomic mechanism, a hormone binds to a receptor, displacing receptor-associated chaperone proteins and enabling dimerization of the receptors. The receptor dimers then act by binding to specific “response element” nucleotide sequences in the DNA to cause alteration to gene expression. By the non-genomic mechanisms, a hormone may bind to cell surface receptors triggering intracellular signal transduction pathways.

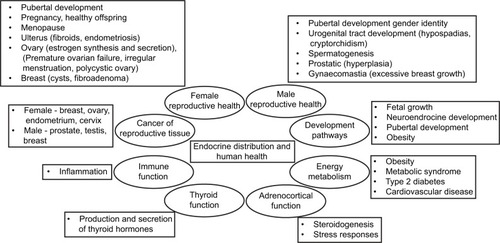

EDCs can interfere in the action of hormones at many different steps, as illustrated in . They may act by altering hormone synthesis in the endocrine gland, or through altering transport of the hormone to the target organ by interfering with the activity of conjugation enzymes or by competing for binding to carrier proteins. Alternatively, they may act through altering metabolism/excretion of the hormone or through competing with the hormone for binding to a receptor in target cells and in so doing to mimic action of steroid hormones (particularly, but not exclusively, in relation to the action of estrogens and androgens) and thyroid hormones.Citation5 Since estrogens and androgens regulate reproductive functions, many of the reported effects of the exposure to EDCs have been on adverse consequences for reproductive health.Citation5 However, physiological consequences have been demonstrated as resulting from disruption to thyroid function and alterations to thyroid hormone levels.Citation5 More widely, adverse effects have also been reported as resulting from alterations to adrenocortical function, impairment of the immune system, and the loss of control on energy metabolism including development of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.Citation5 Prior to and just after birth are especially vulnerable times for exposure to EDCs because disruption of hormonal activity in the developing embryo/fetus or young baby can have consequences for health in adult life most notably on reproductive abilities, brain function, immunity, and metabolic programming.Citation5 For this reason, the passage of EDCs across the placenta from mother to child and postnatal exposure to EDCs in maternal breast milk have become an important topic for research.

Figure 1 Mechanisms of action of EDCs.

Abbreviation: EDCs, endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Man-made EDCs are contained within many agricultural, industrial, and consumer products, which due to their widespread use, have become ubiquitous environmental pollutants. This includes components of pesticides and herbicides used both in an agricultural setting and in urban environments. It includes industrial chemicals and by-products of combustion from vehicles, ships, and aircraft. It also includes plastics which are used widely in building materials, food containers, water bottles and toys, and detergents used for cleaning in both industrial and domestic applications. Paints, glues, chemicals used as flame retardants, and stain resistance coatings also form part of the list. EDCs are also widely used in personal care products (PCPs) for purposes of preservation, deodorant, antiperspirant, conditioning, and fragrance.Citation5

Many varied assay strategies have been developed over the years for identifying compounds with endocrine disrupting properties in order to define a series of events at different levels of biological organization along a pathway which may lead to an adverse health outcome.Citation5 Identification of adverse consequences along a pathway may include altered molecular events, changes to cellular actions, consequences for whole organ responses, or even adverse effects at a population level. Molecular assays include the ability of compounds to bind to specific endocrine receptors followed by assays for genomic actions on gene expression or for non-genomic actions on alterations to defined signal transduction pathways. Actions at a cellular level are most often defined using proliferation of endocrine-sensitive cells as an easily assayable endpoint. Other more specific assays have been developed to measure alterations to synthesis/transport/metabolism/excretion of steroid and thyroid hormones which may be carried out by measuring the activities of key enzymes or levels of secreted hormones using cellular or animal models. Animal models are also widely used to try to predict whole body responses albeit with the caveat of consideration to species differences. It is not always possible to identify actions of every chemical at every step and the challenge for risk assessment is to determine the extent to which early molecular and/or cellular actions may be predictive of later endocrine disease outcomes, and to which effects in animal models can predict for epidemiologically detectable consequences in humans. Specific EDCs which are measurable in air are discussed in the “Sources of exposure to EDCs in air” section together with an outline of the current evidence for their classification as having endocrine disrupting properties.

Sources of exposure to EDCs in air

EDCs are found in both outdoorCitation7 and indoorCitation8 air as VOCs or SVOCs in the gas phase or attached to PM (). Some of the specific-named EDCs are listed in with the sources indicated. For outdoor air, the type and quantity of pollutants vary according to geographical location, according to whether the site is urban or rural,Citation1 and with variations between day and night.Citation9 Although indoor air is supplied by outdoor air, it can be additionally polluted by internal activities such as heating or cooking using solid fuel, and is further influenced in the modern world through reduced ventilation, dependence on air conditioning systems, and usage of chemical-based consumer products.Citation8 It is this new indoor air microenvironment which seems to provide the greatest exposure to EDCs and this will vary according to individual lifestyle choices.

Table 2 Sources of endocrine disrupting chemicals measured in air

Outdoor air may contain a range of EDCs from agricultural spraying, industrial activities, and waste incineration. It may also contain EDCs from combustion including petrol and diesel fumes.Citation7 However, indoor air may be additionally polluted from the use of consumer productsCitation8 in a confined space without adequate ventilation and especially from those in aerosol formats. EDCs are contained in domestic pesticide sprays, air fresheners, laundry detergents, household cleaners, paints, adhesives, and plastics, all of which may be used routinely indoors. They are sprayed as flame retardants and stain resistance coatings onto soft furnishings including beds, chairs, sofas, carpets, and curtains used in domestic, workplace, and commercial indoor environments, and furthermore, they are used in a range of PCPs, many of which are in aerosol formats. EDCs are also found in cigarette smoke and may be measured therefore in the indoor air environment where cigarettes have been smoked. As a result, many EDCs are now measurable in indoor air and in indoor dust, often at higher levels than in outdoor airCitation10,Citation11 as discussed below.

Phthalates

PhthalatesCitation12,Citation13 are esters of phthalic acid which are used as plasticizers not only in plastic products but also in many other consumer goods such as adhesives, paints, air fresheners, and PCPs, making many of the esters high production volume chemicals.Citation14 The phthalates are physically bound into the plastics but not by covalent bonding and so leaching out can occur especially with heat and age. Phthalates are ubiquitous in the indoor environment, and in a study in the Richmond area of the USA were measured as present in 100% of homes.Citation10 The more volatile phthalates, dimethyl phthalate, diethyl phthalate (DEP), and dibutyl phthalate (DBP), are present at higher concentrations in air than the heavier, less volatile phthalates such as di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) and butylbenzylphthalate (BBP) which are more prevalent in house dust.Citation15,Citation16 Higher ambient temperatures are associated with higher air concentrations of phthalatesCitation17 and the presence of polyvinyl chloride flooring has been associated with higher levels of DEHP and BBP in house dust.Citation18,Citation19 Phthalate metabolites have been detected in almost all human urine samples indicating widespread exposure of the population.Citation20 Diet is generally considered as the main route of exposure, but dermal absorption from topical application of PCPs has been demonstratedCitation21 and indoor air may also contribute to the overall burdens. In particular, correlations have been observed between levels of urinary metabolites of DEP, DBP, and BBP with personal indoor air concentrations of the parent phthalates.Citation22,Citation23

Phthalates are well established as EDCs with estrogen/androgen disrupting properties demonstrated.Citation24,Citation25 Early studies in vitro showed that phthalate esters could bind to estrogen receptors, stimulate estrogen-dependent gene expression, and increase growth of estrogen-responsive cells.Citation24,Citation25 Subsequently, many in vivo models have demonstrated that in utero exposure to phthalates impacts negatively on reproductive development in rodents with a striking similarity to the testicular dysgenesis syndrome in humansCitation26 suggesting that phthalate exposure may adversely impact on male reproductive health.

Bisphenol A

Bisphenol A is used for its cross-linking properties in the manufacture of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins, which are now ubiquitous in our daily lives, and is therefore a high production volume chemical.Citation14 It is estimated that >8 billion pounds (3.6 million metric tons) of bisphenol A are produced annually and ~100 tons are released into the atmosphere each year.Citation27 Bisphenol A is now an ubiquitous pollutant of air with levels ranging over several orders of magnitude across different parts of the world, with the highest levels in urban India (200–17,400 pg/m3), but even detectable in polar regions (1–17 pg/m3).Citation28 Correlations have been noted in air between levels of bisphenol A and 1,3,5-triphenylbenzene which is a tracer for plastic burning, suggesting that a source of the atmospheric bisphenol A could be burning of plastic materials.Citation28

Bisphenol A is an established endocrine disrupter.Citation29,Citation30 In vitro, it has been shown to bind to estrogen receptors, to stimulate estrogen-dependent gene expression, and to increase proliferation of estrogen-responsive cells, but it can also bind to androgen receptor and demonstrate antiandrogenic actions. Animal models have demonstrated adverse effects on male reproductive function. However, bisphenol A can also bind to thyroid hormone receptors and in vivo animal models record alterations to thyroid hormone levels. Epidemiological studies suggest a link between bisphenol A exposure in humans and multiple adverse endocrine consequences including not only male and female reproductive functions but also alterations to thyroid hormones, blunted immune function, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity.Citation29,Citation30

Parabens

The population is exposed to the alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens) through their widespread use as antimicrobial agents for preservation of foods, pharmaceuticals, PCPs, and paper goods.Citation31 The main paraben esters used are methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, butylparaben, and benzylparaben. Intact paraben esters are measurable in human tissues including urine, blood, milk, and breast tissue and are widely detected in the environment in water and soil as well as in animal tissues reflecting widespread contamination.Citation31 Unsurprisingly, therefore, parabens are now also being detected in indoor air and house dust. In 2003, a study of homes in Cape Cod detected three paraben esters in indoor air and house dust, with 67% of homes having levels of methylparaben in the indoor air above the reporting limit of 1 ng/m3 and some as high as 21 ng/m3.Citation15 In paired indoor:outdoor air samples from the USA, parabens were only detected in indoor air.Citation10 Parabens have also been detected in house dust in Spain with methylparaben detected at the highest levels up to 2440 ng/g and propylparaben up to 910 ng/gCitation32 which is consistent with these esters also being at the highest levels in human tissues and probably reflecting greater use of these esters in consumer products.Citation31,Citation33

Parabens have been shown to possess estrogenic and androgenic activity in studies in vitro and in vivoCitation33 and their cerning a role in breast cancer development.Citation31 However, it has been their reported adverse effects on male reproductive function following perinatal oral exposure in rodents which stimulated regulatory actions.Citation31,Citation33 More recently, parabens have been shown to possess obesogenic activity.Citation34

Triclosan

Triclosan [5-chloro-2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)phenol] is a chlorinated aromatic compound which has been used as an antimicrobial agent since the 1970s. It was first used as a hospital scrub but has since been incorporated into a wide range of consumer goods including PCPs, kitchen utensils, toys, bedding, and clothing.Citation35 Its extensive use has resulted in triclosan being widely measurable in the environment and in human tissuesCitation36 including urine of the general US population.Citation37 It is therefore not surprising that triclosan is now also being detected in indoor air, with concentrations varying according to location; office space was the most contaminated at 230 pg/m3, then apartment space at 153 pg/m3, followed by house space at 104 pg/m3, and day nursery space at 68 pg/m3.Citation38

Triclosan possesses estrogenic and androgenic activities in vitro.Citation39 Animal models have demonstrated that it can increase uterine weight in immature rodents (uterotrophic assay) and alter steroidogenesis in vivo. Adverse effects have also been reported on reproductive function in vivo in rodents and aquatic species.Citation40

Alkylphenols

Long-chain alkylphenols and their precursors, alkylphenol ethoxylates, are high production volume chemicals used as surfactants in industrial applications and in common consumer goods such as detergents, disinfectants, and surface cleaners.Citation41,Citation42 Alkylphenols such as nonylphenol and octylphenol are now ubiquitously present in the environmentCitation41,Citation42 and in human urine in the Far East.Citation43,Citation44 Studies in outdoor air have demonstrated increased levels above wastewater sitesCitation45 but, generally, alkylphenols are indoor air contaminantsCitation15 which are present at higher concentrations in the gas phase than in PM.Citation46 Alkylphenols were measured as present in 95% of homes of the Richmond area of USA.Citation10

Alkylphenols, especially nonylphenol and octylphenol, are established EDCs with estrogen disrupting properties reported using assays in vitroCitation47 and rodent models in vivo.Citation48

Fragrance compounds

Fragrances have been used since ancient times to mask unpleasant odors. However, traditional plant-based extracts are increasingly being replaced by defined chemical mixtures which are longer lasting.Citation49 Chemical-based fragrance is now added ubiquitously to many consumer products including PCPs, household cleaning agents, air fresheners, and scented candles which are used widely both in homes and in public places such as restrooms, hotels, restaurants, cars, trains, and aeroplanes.Citation49 One survey reported that scented consumer goods emit >100 toxic VOCs including limonene, nitromusks, and polycyclic musksCitation50 which together act to degrade indoor air quality.Citation51 Synthetic musks galaxolide and tonalide are detectable in indoor air, mainly in the gas phase but also in PM.Citation38

Many of these fragrance compounds have now been shown to possess endocrine disrupting properties.Citation49 Various musk fragrance compounds have been demonstrated to possess steroid agonist,Citation52 or antagonist responsesCitation53 in reporter gene assays and some can increase proliferation of estrogen-responsive cells.Citation54 Some adverse developmental effects of nitromusks have been reported in terms of adverse birth outcomes across species.Citation55 One clinical study has reported an association between raised musk xylene and musk ketone levels in women and premenopausal gynecological problems, and notably higher serum levels of musk xylene in women who presented as infertile compared with women who had had at least one pregnancy.Citation56

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)

PBDEsCitation57 are organobromine compounds used as flame retardants in consumer goods including soft furnishings, clothing, and car components. Structurally, they are composed of two halogenated aromatic rings with 209 congeners according to the number and position of the bromine atoms. Due to their widespread use, they have become ubiquitous environmental contaminants of air as well as animal and human tissues. In air, they are distributed between the gas phase and PM, with the heavier (more bromine atoms) congeners increasingly in the PM.Citation58 Levels of PBDEs tend to be not only higher in air of urban than rural areas but also higher in indoor air than in outdoor air.Citation59 Although diet is a source of exposure to PBDEs, indoor air has been suggested to be an important route of exposure for the general populationCitation60,Citation61 together with specific outdoor air occupational exposures of workers at waste recycling plants.Citation62,Citation63

Endocrine disruption is an established component of the toxicity of PBDEs including effects on thyroid hormone functionCitation64 and neurodevelopment.Citation65 In vitro models have shown that some PBDEs or their metabolites can bind to thyroid hormone receptors, and animal models have shown that PBDEs can alter thyroid hormone levels in vivo.Citation64 Early life exposure of animals to PBDEs has revealed alterations to cognitive function/behavior which are critical components for neurodevelopment, and epidemiological studies suggest a similar potential in humans.Citation65

Stain resistance coatings

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) has been used in the manufacture of consumer goods since the 1940s most notably as “Teflon” and “Gore-Tex”. It is used as a water and oil repellent in fabrics and leather, floor waxes, insulators, and firefighting foam. Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) is a fluorosurfactant used most notably as the key ingredient in the fabric protector “Scotchgard” (3M Company, Maple-wood, MN, USA), for which production began in 1949 but is now being phased out. Both PFOS and PFOA are highly stable compounds which persist in the environment and can bioaccumulate. PFOA and PFOS are detectable in outdoor air near manufacturing facilities.Citation66,Citation67 However, they have also been detected more ubiquitously in house dust globally.Citation68–Citation70

Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are developmental toxicants with long-lasting effects in reproductive tissues and on the control of metabolism in rodent models.Citation71,Citation72 In terms of endocrine disrupting activity, PFOA can alter sex hormone levels, and some PFAAs (although not PFOA or PFOS) possess estrogenic activity in being able to stimulate proliferation of estrogen-responsive cells in vitro.Citation72 The main molecular mode of action identified to date seems to be through the activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha.Citation72

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)

PCBsCitation73 were high production organochlorine compounds used as industrial lubricants and coolants, particularly in electrical products due to their low flammability. There are 209 congeners according to the number and configuration of the chlorines, and most were used under trade names as mixtures of congeners. Although their use has been restricted from the 1970s, they have become global pollutants due to their widespread use and environmental stability, and they remain detectable in the air as well as in animal and human tissues.Citation73 Levels in air tend to be higher in urban than rural or remote areas, and with the congener composition varying between cities indicating an influence of local sources.Citation74–Citation77 Levels in indoor air can be from 10× to 100,000× higher than outdoor air probably due to their presence in building materials and consumer goods.Citation8 Diet is considered to be the major source of PCB exposure because PCBs, which are lipophilic, pass up the food chain dissolved in animal fat. However, some studies suggest that dietary levels of PCBs are decreasing faster than indoor air concentrations, making inhalation an increasingly important route of exposureCitation61 especially in day care centersCitation78 and in homes with certain wood floor finish.Citation8

Endocrine disruption is a component of the overall toxicity profile of PCBs but the existence of 209 individual congeners presents challenges both for the large number of assays needed to assess effects of so many different compounds (and their metabolites) and for assessing the effects of environmentally relevant mixtures, especially since congener mixtures in human tissues may not be directly reflective of industrial mixtures originally released. Much effort has been given over to assaying the estrogenic potential of the 209 congeners but detailed studies showing estrogenic activity in vitro and in vivo of one congenerCitation79 have to be supplemented by in silico studies to provide a broader overall picture.Citation80 Since estrogen exposure is an established risk factor for breast cancer, much effort has been devoted over the years to epidemiological studies of PCB body burdens in patients with breast cancer.Citation81 Such studies remain conflicting and the role of PCBs in breast cancer unresolved. Other effects of PCBs which are better established are their ability to disrupt thyroid homeostasis leading to alterations to thyroid hormone levelsCitation82 and their neurotoxic actions.Citation83 Prenatal exposure from the transplacental passage of PCBs and postnatal exposure from PCBs in breast milk have been suggested to be linked to impairment of neurodevelopment.Citation83 In older adults, increased serum levels of PCBs have been linked to cognitive dysfunction typical of neurodegenerative disease.Citation84,Citation85

Polychlorinated dibenzodioxins (PBDDs) and polychlorinated dibenzofurans (PBDFs)

PBDDsCitation86 are by-products of combustion and chemical processes. There are 75 congeners of which the most toxic is 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin which accounts for about 10% of dioxin exposure. A main source of dioxins is from the incineration of urban wasteCitation87 and the dioxins are transported from the site of combustion through the air, to land in the environment, be washed off by rain water into rivers and lakes and thence pass up the food chain dissolved in animal fat. PBDFsCitation86 are also by-products of incineration of organochlorine waste and may be inhaled from coal tar, coal tar derivatives, and creosote. Dioxins are measured in outdoor air across the globe from the USACitation88 to China.Citation89 Levels are generally higher in urban areas than rural areas and can be detected at elevated levels near solid waste plants.Citation90 Dioxins are also measurable in indoor dust but levels are usually reflective of outdoor conditions.Citation91 However, it has been reported that burning incense can increase dioxin levels in indoor air which may therefore cause raised levels in specific indoor environments such as temples or churches.Citation92

Dioxins have a broad spectrum of toxicity which includes endocrine disrupting ability. In laboratory animals, they are known to give rise to weight loss, reproductive toxicity, developmental toxicity, tumorigenesis, and immune system dysfunction.Citation93 Endocrine actions are thought to be largely mediated through aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-mediated mechanisms,Citation93,Citation94 but there are also defined estrogen antagonist activities mediated through cross-talk between estrogen receptor and AhR pathways.Citation94 Clinical studies have reported detrimental effects on human semen quality.Citation95,Citation96

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

PAHs are a group of organic compounds with two or more fused aromatic rings and which are produced by incomplete combustion of organic materials either naturally from burning of biomass or from human activities such as vehicle emissions, coal burning plants, smoking cigarettes, and from cooking with solid fuels.Citation97 PAHs are released into the atmosphere from where they can be ubiquitously deposited into soil and water as persistent contaminants. In air, low-molecular weight PAHs tend to occur predominantly in the gas phase whereas larger (5+ rings) PAHs tend to be found in PM.Citation97 They are measurable globally in outdoor air, although at generally higher levels in less developed countries and at higher levels in urban environments.Citation97 Outdoor air PAHs are generated naturally by forest fires and volcanoes but the main sources in the modern world are from industrial plants, waste incineration, and vehicle emissions.Citation97 PAHs can be measured in indoor air as well as outdoor airCitation98 with the levels in indoor air influenced by the burning of solid fuels for cooking and by smoking of cigarettes.Citation99

PAHs have a known toxicity profile and many are genotoxic/carcinogenic.Citation100 Their carcinogenicity is thought to result from the ability of some PAHs to form reactive diol epoxide intermediates catalyzed by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes (which may be induced themselves by PAHs through an AhR-mediated mechanismCitation93,Citation94) and then the subsequent covalent binding of these intermediates to DNA. Carcinogenicity of other PAHs may originate from their ability to generate reactive oxygen species resulting in oxidative stress and inflammatory responses.Citation101 However, PAHs are also now regarded as EDCs.Citation101 Some PAHs have been reported to act as agonists and others as antagonists of estrogen action.Citation101 Agonist actions are mediated by hydroxylated metabolites (with the metabolic conversion itself also mediated by CYP and this inducible by PAHs through an AhR-mediated mechanism) whilst antagonist actions are mediated as described above for the dioxins through cross-talk between AhR and estrogen receptor pathways.Citation94

Pesticides

Pesticides are used widely not only in agricultural settings but also in domestic context from off-the-shelf formulations and in aerosol formats. Some pesticides are organochlorine compounds such as DDT and chlordane which are being phased out due to their environmental persistence. Other pesticides are organophosphates such as chlorpyrifos, carbamates, or pyrethroids. Semi-volatile pesticides are detectable in both indoor air and indoor dust whilst nonvolatile pesticides are usually found only in dust.Citation15,Citation102 Concentrations in air are generally higher in warmer weather which increases pesticide volatility, and are therefore higher in places with warmer climates and higher in summer than winter months.Citation102 They can be detected in both outdoor and indoor air but degradation rates tend to be lower indoors which typically gives higher levels in indoor air.Citation15,Citation103 Many of the banned organochlorine pesticides such as DDT, chlordane, and methoxychlor are established EDCs with estrogenic activities demonstrated in in vitro assays.Citation104,Citation105 However, other pesticides are also endocrine disrupting with some pyrethroids possessing androgen and oestrogen disrupting propertiesCitation106–Citation109 and chlorpyrifos having thyroid hormone disrupting actions.Citation110,Citation111

Herbicides

Glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine)Citation112 is a broad spectrum systemic herbicide used to kill broadleaf weeds and grasses. It was first marketed in the 1970s under the trade name “Roundup” (Monsanto Company, MO, USA), and was widely adopted in conjunction with glyphosate-resistant crops enabling farmers to kill weeds more effectively without killing the crops. However, it is now also in wide use in the urban environment including domestic gardens. Glyphosate has endocrine disrupting properties, including an ability to interfere in steroidogenesisCitation113 and estrogenic activity in in vitro assays of estrogen-responsive gene expression and proliferation.Citation114 More recent studies indicate that in utero exposure can cause thyroid imbalance in male rats.Citation115 The extent to which it is a human carcinogen remains under debate.Citation116 Atrazine is a herbicide used widely for broadleaf crops, but also on golf courses and residential lawns. It was banned in the European Union in 2004 but remains in use in many other parts of the world. In USA, as of 2014, atrazine remained the second most applied herbicide after glyphosate. Its endocrine disrupting properties were first described in terms of feminization of male gonads in amphibiansCitation117 but many other studies now describe its ability to cause reproductive dysfunction in rodent and fish models.Citation118 Both of these herbicides have now been detected in air and rain in the Mississippi area of the USA.Citation119 In the 2007 sampling, glyphosate was detected in >75% and atrazine in >80% of air and rain samples.Citation119

Metals

Although most EDCs are organic compounds, some metal ions have also been shown to be capable of interfering in estrogen action and these inorganic xenoestrogens have been termed metalloestrogens.Citation120 Metalloestrogens include aluminum, antimony, arsenite, barium, cadmium, chromium [Cr(II)], cobalt, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, selenite, tin, and vanadate.Citation120 Pollution of the ecosystem with heavy metals is widespread and some can be detected in indoor dustCitation121 which implies their presence in the indoor air environment. However, there are some situations in relation to indoor air which deserve special consideration. Cadmium is contained in cigarette smoke and has many endocrine toxicities.Citation122,Citation123 Aluminum is used as an active antiperspirant agent in underarm cosmetics often in aerosol formats and aluminum-based antiperspirant use has been linked to breast cancer.Citation124 In consideration of the potential adverse effects of inhalation of aluminum from antiperspirant sprays, it is noteworthy that inhalation of aluminum powder by miners to protect against silicosis gave rise to some early signs of reduced cognitive function in exposed workers which might be indicative of neuroendocrine disruption.Citation125

Contribution of EDCs in air to overall human body burdens

From the research discussed above in the section entitled “Sources of exposure to EDCs in air”, it is clear that air pollution includes many EDCs and that EDCs are entering human tissues. However, the question then remains as to the extent to which EDCs in air can contribute to the overall EDC body burdens. Over the past several decades, many cases of endocrine disruption in aquatic organisms have been linked directly to concentrations of EDCs in the water environment leading to reproductive problems and consequent population declines.Citation126,Citation127 Early work showed that tributyltin in antifouling paints used on the underside of ships was causing imposex and extensive loss of bivalves and gastropods in harbor watersCitation128 which after the restriction of tributyltin enabled recovery of marine populations.Citation129 Another similar documented scenario has been described in Lake Apopka in Florida, USA following a spill of the pesticide difocol which caused reproductive problems in the alligator population.Citation130 However, the long-debated question remains as to whether similar effects might occur in terrestrial animals which inhale air through lungs rather than taking in water over gills. One complicating factor for terrestrial animals, and in particular the human population, is that the exposure to EDCs occurs nowadays through multiple routes, not only inhalation but also oral and dermal,Citation5 making it difficult to ascertain the proportion of body burdens which arrive through each route of entry. For all the EDCs discussed above, published evidence demonstrates their presence in air and that they are measurable in human tissues. For some EDCs, there is accumulating evidence that they are linked to a range of human health issues including female and male reproductive problems, endocrine cancers, thyroid and adrenal dysfunction, developmental abnormalities, immune dysfunction, and disorders of energy metabolism,Citation5 as summarized in . However, what remains uncertain is the extent to which inhalation is a source of the entry of EDCs to the human body. Furthermore, not only is there a question as to the relative importance of inhalation of outdoor versus indoor air, of inhalation of EDCs in gaseous versus PM format, and of inhalation of PM of different sizes, but it has also been recently suggested that for some semi-volatile EDCs, dermal uptake from air may be greater than uptake from inhalation.Citation131 This is especially important for considerations of entry of EDCs such as the paraben esters, which would be metabolized in the liver by esterase activity when entering systemically by oral or inhaled routes, but which would escape breakdown in the liver when entering locally by the dermal route.Citation31,Citation33

Figure 2 Outline of the influences of EDCs on human health.

Abbreviation: EDCs, endocrine disrupting chemicals.

Effects of EDCs in air on human endocrine health

Dense smogs mixed with sulfur dioxide and smoke in 1930 over the Meuse Valley in BelgiumCitation132 and in 1952 in London, UKCitation133 demonstrated the lethality of air pollution, and air pollution is now recognized as a significant factor for many respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.Citation1–Citation4 Air-borne pollutants also cause disruption to the endocrine system but this is less often discussed, probably because the effects are more chronic than acute and therefore more difficult to link to specific exposures. Studies using environmental mixtures of EDCs collected in samples of indoor air demonstrate that air does contain compounds with demonstrable estrogenic and androgenic activities when applied to in vitro assay systems.Citation11 However, whether the presence of these EDCs in indoor air is a specific cause of or contributes to any specific adverse human health outcome is difficult to ascertain due to the many different routes of exposure to these same compounds (diet, dermal) in addition to air.

Given the uncertainties of the relative contributions of EDCs from different sources (air, diet, dermal), it is pertinent to begin a discussion of the effects on human endocrine health with specific scenarios where the source of exposure is undoubtedly from air. One specific example where air-borne EDCs can affect the endocrine system is from cigarette smoke, and effects have also even been noted for passive smoking indicating air-borne contaminants as the source.Citation134,Citation135 Other special scenarios of air-borne EDCs affecting human endocrine health are discussed in relation to occupational exposure to air-borne material from hops, the use of fragranced air fresheners in indoor spaces, and health issues surrounding traffic-related air pollution.

Cigarette smoking

Tobacco smoke contains a complex mixture of compounds including EDCs and is known to cause alterations to many hormone levels, thus defining cigarette smoke as endocrine disrupting.Citation134,Citation135 Smoking is known to exert effects on the thyroid gland and is an accepted risk factor for thyroid disease including Graves’ hyperthyroidism. It causes alterations to thyroid hormone levels, increasing both serum triiodothyronine and thyroglobin concentrations,Citation136 and since even paternal smoking increases infant serum thyroglobin, this implies air-borne transfer. Smoking also stimulates the release of several pituitary hormones, causing increases in plasma levels of prolactin, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, growth hormone, and arginine vasopressin proportional to the nicotine intake.Citation137–Citation140

The levels of many steroid hormones are also affected by smoking. In terms of adrenal steroids, smoking causes a rise in circulating cortisol,Citation141 which is decreased on cessation of smoking,Citation142 and also in plasma aldosterone and adrenal androgens.Citation134,Citation135 Smoking is known to impact on female reproductive healthCitation143 at least partly due to effects on the estrogen metabolism together with increased levels of steroid hormone binding globulin which results in lowering concentrations of circulating free estrogens.Citation134,Citation135 This results in alterations to the menstrual cycle and risk of anovulation.Citation143–Citation145 The reduced estrogen levels are also considered to be the explanation of increased osteoporosis in women who smoke.Citation134,Citation135

Smoking has also been linked to insulin resistance in a dose-dependent manner and predisposes to metabolic syndrome.Citation134,Citation135,Citation146 More recently, smoking has further been linked to obesity. Whilst moderate smokers have reduced body weight, the dose dependency of weight gain with smoking is actually a U-shaped relationship such that heavy smokers can gain weight, which is in accordance with the non-monotonic nature of endocrine disrupting mechanisms.Citation147 Of current concern are studies which now link prenatal exposure to smoking as a cause of childhood obesityCitation148,Citation149 and even from paternal smoking which implies air-borne components.Citation150 Imprinting mechanisms imply that there may also be consequences for future generations without the need for further exposureCitation151 as has been demonstrated for EDCs.Citation5

Occupational exposure to hops

Phytoestrogens are compounds contained within plant material and which possess estrogenic properties.Citation152 One special scenario where air-borne phytoestrogens have been reported to adversely influence human endocrine health has been in the context of the hop industry, where inhalation of dust from the preparation of hop material has been known to cause menstrual disturbances in female workers for many years.Citation153 The component compound has now been identified as 8-prenylnaringenin,Citation153 and this occupational exposure scenario demonstrates the ability of air-borne EDCs to cause adverse endocrine effects in women.

Air fresheners and scented products

Air fresheners and scented products are now ubiquitously used in indoor environments to mask unpleasant odors and to create a pleasant smell by emitting a range of volatile synthetic fragrance compounds, many of which are EDCs as detailed earlier. Adverse human health effects are now being increasingly documented following exposure to these products and include migraine headaches, asthma attacks, contact dermatitis, and mucosal symptoms,Citation49,Citation154 but the extent to which these health problems stem from hormonal disturbances remains to be ascertained. However, EDCs, such as phthalates and musks, are contained in these products and are now being suspected as contributing to hormonal imbalances underlying the excessive breast growth of men in gynecomastia.Citation49 One recent study has identified gynecomastia in young boys following dermal exposure to lavender and tea-tree oilsCitation155 and therefore inhalation of such oils could potentially also pose a problem for endocrine health.

Insulin resistance and air pollution

Glucose homeostasis is dependent on hormonal control, most notably through the actions of insulin and glucagon and also adrenalin, cortisol, and estrogens, and there is increasing evidence that EDCs may be contributing to causing glucose imbalances in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.Citation5 Type 2 diabetes is one of the fastest growing worldwide health problemsCitation5 and therefore causative factors which could be avoided would offer a preventative strategy. Several studies now report a link between PM from traffic-related air pollution and insulin resistanceCitation156–Citation158 and the most recent paper reports PM to be a risk factor for type 2 diabetes especially in a subsection of the population with a prediabetic condition.Citation158 It will now be important to identify the components in the PM of air traffic pollution which may be causative and whether these may be EDCs.

Reproductive abnormalities and air pollution

EDCs are known to impact on both female and male reproductive health.Citation5 Concerns for adverse effects of exposure to exogenous estrogen stem from the development of rare vaginal cancers in women prescribed diethylstilboestrol during pregnancy and then the subsequent adverse reproductive health outcomes in both their daughters and sons who were only exposed in utero.Citation159 More recent research is beginning to reveal evidence that exposures to various EDCs can lead to a range of adverse reproductive outcomes, such as for the link between exposure to bisphenol A and development of polycystic ovary syndrome,Citation160 and between exposure to phthalates and testicular dysgenesis syndrome.Citation26 In terms of this review specifically, the question is as to how much of the relevant exposures originate from inhalation of air compared to oral and dermal exposures. Traffic-related studies point more specifically to an involvement of air-borne EDCs in infertility.Citation161 A recent scoping review indicated that exposure to PAHs impacted most notably on female reproductive health in terms of reduced fertility and pregnancy viability which might be explained by the impact of PAHs on the key hormonal regulators luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, gonadotrophin releasing hormone, and the enzyme aromatase responsible for synthesis of estrogens.Citation162 SVOCs present in the air and PM are suspected also of having effects on male reproductive function in particular through reduced sperm quality and reduced serum testosterone concentrations.Citation163 A recent study has also indicated that exposure to air pollution through early life was negatively associated with pubertal stage in both boys and girls although the type of pollutant varied (PM10 for girls, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide for boys).Citation164 In another study of traffic-related air pollution, it was found that girls reached puberty several months earlier in residential areas closer to major roadsCitation165 but again the culprit chemicals remain to be identified.

Developmental abnormalities and air pollution

Transplacental transfer of EDCs from a mother to the embryo/fetus is increasingly reported as causing hormonal disruption to developmental processes with long-term consequences both in adult life and for future generations.Citation5 Exposure to PM2.5 air pollution has been linked to adverse gestational outcomes,Citation166 but a recent epidemiological study in Belgium has reported that PM2.5 exposure in the third trimester of pregnancy is associated not only with reduced birth weight but also alteration to fetal thyroid hormones.Citation167

Endocrine cancers and air pollution

Cancer is a complex, multistep process, often taking many decades for visible symptoms to become evident, and requiring exposure to multiple agents for development of all the hallmarks,Citation168 which in the case of endocrine-responsive cancers, may also involve exposure to EDCs.Citation5 Although airborne cigarette smoke is the main cause of lung cancer, other components of air pollution can also increase the incidence of lung cancerCitation169,Citation170 and air-borne asbestos particles are a main cause of mesothelioma through disruption to cytokinesis in the target cells.Citation171 Air pollution is therefore now considered to be carcinogenicCitation172 and contains multiple agents capable of causing genomic instabilityCitation173 which is an underlying characteristic of cancer development.Citation168 However, evidence is also accumulating that the incidence of endocrine-sensitive breast cancer may also be increased by traffic-related air pollutionCitation174–Citation176 and especially in relation to PAH content.Citation177 The mechanism remains to be unraveled, specifically whether the air pollutants may be providing just the source of genotoxic compounds or provide also the endocrine stimuli from EDCs. Another endocrine-sensitive cancer is cervical cancer, and although human papilloma virus (HPV) infection is a main cause of cervical cancer, not all women infected with HPV develop cervical cancer indicating the involvement of other risk factors. In this context, it may be significant that traffic-related air pollutants, including PAHs, have been shown to increase cervical dysplasia, a precursor lesion for cervical cancer.Citation178

Conclusion and data gaps

In conclusion, there is a considerable body of evidence documenting the presence of EDCs in both outdoor and indoor air, that EDCs are entering human tissues, and that EDCs are impacting on human endocrine health. However, the extent to which air-borne EDCs contribute to the overall human body burdens of EDCs is unknown, and instances where endocrine abnormalities can be related directly and solely to an airborne source of EDCs are few. It is likely that the overall environmental reality is that human body burdens of EDCs originate from a range of exposures including diet and dermal as well as air, and that most human health effects result from chemical mixtures rather than individual chemicals.

Recommendations and future directions

Despite the uncertainty of source, we should not deter from the urgent need to reduce exposure to EDCs if global endocrine health is to be preserved, and this will ultimately require reducing exposure from all sources including air as well as oral and dermal. Whilst it is increasingly acknowledged that personal choices can result in reduced oral and dermal exposures to EDCs, the same could also be true for inhalation by personal choices of reducing use of chemicals, especially in indoor spaces and in aerosol format, and increasing ventilation in indoor spaces. A public education program in the handling of chemical-based products would be highly appropriate in the modern world, and it is highly likely that new public awareness could have immense health benefits. It is interesting that individuals with asthma have been reported to have a lower risk of breast cancer,Citation179 and it could be speculated that the reduced cancer risk might originate from an awareness of asthma causing pollutants, which then spills over into a new lifestyle of pollution avoidance.

Some of the challenges in understanding the action of EDCs are different from generally accepted toxicological approaches, not least because their action through biological receptor-based signaling pathways enables them to act at much lower concentrations than the nonspecific actions of general toxicity, but also because many of their responses are not predictable and may follow non-monotonic patterns.Citation147 Furthermore, since multiple different compounds may act by a similar mechanism through binding to the same receptor, they can substitute for one anotherCitation180 and thus confound epidemiological studies, which tend to be based on the assumption of a single component alone being causative. In multistep processes, such as cancer, they may also be able to act by complementary mechanisms,Citation180 which would also confuse epidemiological work. Indeed, a recent multinational project has concluded that unraveling the causes of cancer will need to take into account the effects of long-term low-dose exposures to complex mixtures of chemicals.Citation181 In this context, there needs to be a new realization not only by the general public but also by regulatory bodies that the action of EDCs may be far more complex than currently accredited, involving additive and/or complementary actions of a wide range of different chemical compounds from a large number of different sources to which air pollution needs to be increasingly added as a significant component.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationFactsheet 313. Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health [updated September 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs313/en/

- World Health OrganizationFactsheet 292. Household air pollution and health [updated February 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs292/en/

- NajjarYSHGaseous pollutants formation and their harmful effects on health and environmentInnovative Energy Policies20111 E10120318

- AndersonJOThundiyilJGStolbachAClearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human healthJ Med Toxicol2012816617522194192

- DarbrePDEndocrine Disruption and Human HealthElsevierNew York2015

- Report of the Proceedings of the European workshop on the impact of endocrine disrupters on human health and wildlifeWeybridge, UKReport EUR17549 of the Environment and Climate Change Research Programme of DGXII of the European Commission1996

- TeilMJMoreau-GuigonEBlanchardMEndocrine disrupting compounds in gaseous and particulate outdoor air phases according to environmental factorsChemosphere20161469410426714291

- RudelRRPerovichLJEndocrine disrupting chemicals in indoor and outdoor airAtmos Environ200943170181

- NovakJGlesyJPHilscherovaKIn vitro effects of pollutants from particulate and volatile fractions of air samples – day and night variabilityEnviron Sci Pollut Res20132066206627

- RudelRADodsonREPerovichLJSemivolatile endocrine-disrupting compounds in paired indoor and outdoor air in two northern California communitiesEnviron Sci Technol2010446583659020681565

- OziolLAlliotFBottonJFirst characterization of the endocrine-disrupting potential of indoor gaseous and particulate contamination: comparison with urban outdoor air (France)Environ Sci Pollut Res Int2017243142315227858277

- KamrinMAPhthalate risks, phthalate regulation and public health: a reviewJ Toxicol Environ Health Part B200912157174

- HuangPCLiouSHHoIKChiangHHuangHIWangSPhthalates exposure and endocrinal effects: an epidemiological reviewJ Food Drug Analysis201220719733

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)The 2004 OECD List of High Production Volume ChemicalsParisEnvironment Directorate2004

- RudelRACamannDESpenglerJDKornLRBrodyJGPhthalates, alkylphenols, pesticides, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds in indoor air and dustEnviron Sci Technol2003374543455314594359

- HeudorfUMersch-SundermannVAngererJPhthalates: toxicology and exposureInt J Hyg Environ Health200721062363417889607

- UhdeEBednarekMFuhrmannFSalthammerTPhthalic esters in the indoor environment – test chamber studies on PVC coated wall-coveringsIndoor Air20011115015511521498

- BornehagCGSundellJWeschlerCJThe association between asthma and allergic symptoms in children and phthalates in house dust: a nested case-control studyEnviron Health Perspect20041121393139715471731

- BornehagCGLundgrenBWeschlerCJSigsgaardTHagerhed-EngmanLSundellJPhthalates in indoor dust and their association with building characteristicsEnviron Health Perspect20051131399140416203254

- SilvaMJBarrDBReidyJAUrinary levels of seven phthalate metabolites in the U.S. population from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2000Environ Health Perspect200411233133814998749

- JanjuaNRFrederiksenHSkakkebaekNEWulfHCAnderssonAMUrinary excretion of phthalates and paraben after repeated whole-body topical application in humansInt J Androl20083111813018194284

- AdibiJJPereraFPJedrychowskiWPrenatal exposures to phthalates among women in New York City and Krakow, PolandEnviron Health Perspect20031111719172214594621

- AdibiJJWhyattRMWilliamsPLCharacterization of phthalate exposure among pregnant women assessed by repeat air and urine samplesEnviron Health Perspect200811646747318414628

- JoblingSReynoldsTWhiteRParkerMGSumpterJPA variety of environmentally persistent chemicals, including some phthalate plasticizers, are weakly estrogenicEnviron Health Perspect19951035825877556011

- HarrisCAHenttuPParkerMGSumpterJPThe estrogenic activity of phthalate esters in vitroEnviron Health Perspect19971058028119347895

- HowdeshellKLHotchkissAKGrayLECumulative effects of anti-androgenic chemical mixtures and their relevance to human health risk assessmentInt J Hyg Environ Health201722017918827923611

- StaplesCADornPBKleckaGMA review of the environmental fate, effects, and exposures of bisphenol AChemosphere199836214921739566294

- FuPKawamuraKUbiquity of bisphenol A in the atmosphereEnviron Pollut20101583138314320678833

- RubinBSBisphenol A: an endocrine disruptor with widespread exposure and multiple effectsJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol2011127273421605673

- RochesterJRBisphenol A and human health: a review of the literatureReprod Toxicol20134213215523994667

- DarbrePDHarveyPWParabens can enable hallmarks and characteristics of cancer in human breast epithelial cells: a review of the literature with reference to new exposure data and regulatory statusJ Appl Toxicol20143492593825047802

- RamirezNMarceRMBorrullFDetermination of parabens in house dust by pressurised hot water extraction followed by stir bar sorptive extraction and thermal desorption–gas chromatography–mass spectrometryJ Chromatog A201112186226623121802088

- DarbrePDHarveyPWParaben esters: review of recent studies of endocrine toxicity, absorption, esterase and human exposure, and discussion of potential human health risksJ Appl Toxicol20082856157818484575

- DarbrePEndocrine disruptors and obesityCurr Obes Rep20176182728205155

- DannABHontelaATriclosan: environmental exposure, toxicity and mechanisms of actionJ Appl Toxicol20113128531121462230

- HuangCLAbassOKYuCPTriclosan: a review on systematic risk assessment and control from the perspective of substance flow analysisSci Total Environ2016566–567771785

- LiSZhaoJWangGUrinary triclosan concentrations are inversely associated with body mass index and waist circumference in the US general population: Experience in NHANES 2003–2010Int J Hyg Environ Health201521840140625823951

- LaborieSMoreau-GuigonEAlliotFDesportesAOziolLChevreuilMA new analytical protocol for the determination of 62 endocrine-disrupting compounds in indoor airTalanta2016142132141

- GeeRHCharlesATaylorNDarbrePDOestrogenic and androgenic activity of triclosan in breast cancer cellsJ Appl Toxicol200828789117992702

- WangCFTianYReproductive endocrine-disrupting effects of triclosan: population exposure, present evidence and potential mechanismsEnviron Pollut201520619520126184583

- NimrodACBensonWHEnvironmental estrogenic effects of alkylphenol ethoxylatesCrit Rev Toxicol1996263353648726166

- KovarovaJBlahovaJDivsovaLSvobodovaZAlkylphenol ethoxylates and alkylphenols – update information on occurrence, fate and toxicity in aquatic environmentPol J Vet Sci20131676377224597317

- ParkHKimKUrinary levels of 4-nonylphenol and 4-t-octylphenol in a representative sample of the Korean adult populationInt J Environ Res Public Health201714E93228820486

- PengFJiWZhuFA study on phthalate metabolites, bisphenol A and nonylphenol in the urine of Chinese women with unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortionEnviron Res201615062262827156842

- DachsJVan RyDAEisenreichSJOccurrence of estrogenic nonylphenols in the urban and coastal atmosphere of the lower Hudson river estuaryEnviron Sci Technol19993326762679

- WeschlerCJIndoor-outdoor relationships for non-polar organic constituents of aerosol particlesEnviron Sci Technol198418648652

- WhiteRJoblingSHoareSASumpterJPParkerMGEnvironmentally persistent alkylphenolic compounds are estrogenicEndocrinology19941351751828013351

- LawsSCCareySAFerrellJMBodmanGJCooperRLEstrogenic activity of octylphenol, nonylphenol, bisphenol A and methoxychlor in ratsToxicol Sci20005415416710746942

- PatelSFragrance compounds: the wolves in sheep’s clothingsMed Hypotheses201710210611128478814

- PoteraCScented products emit a bouquet of VOCsEnviron Health Perspect2011119A1621196139

- UhdeESchulzNImpact of room fragrance products on indoor air qualityAtmos Environ2015106492502

- MoriTIidaMIshibashiHHormonal activity of polycyclic musks evaluated by reporter gene assayEnviron Sci20071419520217762842

- Van der BurgBSchreursRLindenSSeinenWBrouwerASonneveldEEndocrine effects of polycyclic musks: do we smell a rat?Int J Androl20083118819317971161

- BitschNDudasCKornerWEstrogenic activity of musk fragrances detected by the E-screen assay using human MCF-7 cellsArch Environ Contam Toxicol20024325726412202919

- TaylorKMWeisskopfMShineJHuman exposure to nitro musks and the evaluation of their potential toxicity: an overviewEnviron Health2014131724405644

- EisenhardtSRunnebaumBBauerKGerhardINitromusk compounds in women with gynecological and endocrine dysfunctionEnviron Res Section A200187123130

- World Health OrganizationBrominated diphenyl ethersEnvironmental Health Criteria 1994 Number 162. Available from: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc162.htm

- VivesICanutiECastro-JimenezJOccurrence of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in Lake Maggiore (Italy and Switzerland)J Environ Monit2007958959817554431

- HazratiSHarradSCauses of variability in concentrations of poly-chlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor airEnviron Sci Technol2006407584758917256498

- AllenJGMcCleanMDStapletonHMNelsonJWWebsterTFPersonal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in residential indoor airEnviron Sci Technol2007414574457917695899

- HarradSHazratiSIbarraCConcentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls in indoor air and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in indoor air and dust in Birmingham, United Kingdom: implications for human exposureEnviron Sci Technol2006404633463816913117

- DengWJZhengJSBiXHFuJMWongMHDistribution of PBDEs in air particles from an electronic waste recycling site compared with Guangzhou and Hong Kong, South ChinaEnviron Int2007331063106917631964

- CahillTMGroskovaDCharlesMJSanbornJRDenisonMSBakerLAtmospheric concentrations of polybrominated diphenyl ethers at near source sitesEnviron Sci Technol2007416370637717948781

- ZhouTTaylorMMDeVitoMJCroftonKMDevelopmental exposure to brominated diphenyl ethers results in thyroid hormone disruptionToxicol Sci20026610511611861977

- HerbstmanJBMallJKDevelopmental exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers and neurodevelopmentCurr Environ Health Res20141101112

- BartonCAButlerLEZarzeckiCJCharacterizing perfluorooctanoate in ambient air near the fence line of a manufacturing facility: comparing modeled and monitored valuesJ Air Waste Manag Assoc200656485516499146

- SuHLuYWangPPerfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in indoor and outdoor dusts around a mega fluorochemical industrial park in China: implications for human exposureEnviron Int20169466767327393120

- KnobelochLImmPAndersonHPerfluoroalkyl chemicals in vacuum cleaner dust from 39 Wisconsin homesChemosphere20128877978322542201

- MoriwakiHTakatahYArakawaRConcentrations of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in vacuum cleaner dust collected in Japanese homesJ Environ Monit2003575375714587845

- ErikssonUKarrmanAWorld-wide indoor exposure to polyfluoroalkyl phosphate esters (PAPs) and other PFASs in household dustEnviron Sci Technol201549145031451126000882

- JensenAALeffersHEmerging endocrine disrupters: perfluoroalkylated substancesInt J Androl20083116116918315716

- WhiteSSFentonSEHinesEPEndocrine disrupting properties of perfluorooctanoic acidJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol2011127162621397692

- World Health OrganizationPolychlorinated biphenyls and terphenylsEnvironmental Health Criteria 1992 Number 140. Available from: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc140.htm

- HarnerTShoeibMDiamondMSternGRosenbergBUsing passive air samplers to assess urban-rural trends for persistent organic pollutants. 1. Polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticidesEnviron Sci Technol2004384474448315461152

- Motelay-MasseiAHarnerTShoeibMDiamondMSternGRosenbergBUsing passive air samplers to assess urban-rural trends for persistent organic pollutants and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. 2. Seasonal trends for PAHs, PCBs, and organochlorine pesticidesEnviron Sci Technol2005395763577316124313

- ShenLWaniaFLeiYDTeixeiraCMuirDCXiaoHPolychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the North American atmosphereEnviron Pollut200614443444416603288

- JamshidiAHunterSHazratiSHarradSConcentrations and chiral signatures of polychlorinated biphenyls in outdoor and indoor air and soil in a major U.K. conurbationEnviron Sci Technol2007412153215817438756

- WilsonNKChuangJCLyuCLevels of persistent organic pollutants in several child day care centersJ Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol20011144945811791162

- NesaretnamKCorcoranDDilsRRDarbreP3,4,3′,4′-Tetrachlo-robiphenyl acts as an estrogen in vitro and in vivoMol Endocrinol1996109239368843409

- RuizPIngaleKWheelerJSMumtazM3D QSAR studies of hydroxylated polychlorinated biphenyls as potential xenoestrogensChemosphere20161442238224626598992

- BrodyJGMoysichKBHumbletOAttfieldKRBeehlerGPRudelRAEnvironmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studiesCancer200710912 Suppl2667271117503436

- TurykMEAndersonHAPerskyVWRelationships of thyroid hormones with polychlorinated biphenyls, dioxins, furans, and DDE in adultsEnviron Health Perspect20071151197120317687447

- WinnekeGWalkowiakJLilienthalHPCB-induced neurodevelopmental toxicity in human infants and its potential mediation by endocrine dysfunctionToxicology2002181–182161165

- BouchardMFOulhoteYSagivSKSaint-AmourDWeaveJPoly-chlorinated biphenyl exposures and cognition in older U.S. adults: NHANES (1999–2002)Environ Health Perspect2014122737824275543

- PrzybylaJHousemanEASmitEKileMLA path analysis of multiple neurotoxic chemicals and cognitive functioning in older US adults (NHANES 1999–2002)Environ Health20171611128049482

- World Health OrganizationPolychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofuransEnvironmental Health Criteria 1989 Number 88. Available from: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc88.htm

- ShibamotoTYasuharaAKatamiTDioxin formation from waste incinerationRev Environ Contam Toxicol200719014117432330

- DwyerHThemelisNJInventory of U.S. 2012 dioxin emissions to atmosphereWaste Manag20154624224626297638

- WangPZhangQLiYMatsikoJZhangYJiangGAirborne persistent toxic substances (PTSs) in China: occurrence and its implication associated with air pollutionEnviron Sci Process Impacts20171998399928745352

- CaseriniSCernuschiSGiuglianoMAir and soil dioxin levels at three sites in Italy in proximity to MSW incineration plantsChemosphere2004541279128714659420

- DezielNCNuckolsJRJonesRRComparison of industrial emissions and carpet dust concentrations of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans in a multi-center U.S. studySci Tot Environ201758012761286

- HuMTChenSJHuangKLCharacterisation of, and health risks from, polychlorinateddibenzo-pdioxins/dibenzofurans from incense burned in a templeSci Tot Environ200940748704875

- OtarolaGCastilloHMarcelliniSAryl hydrocarbon receptor-based bioassays for dioxin detection: thinking outside the boxJ Appl Toxicol Epub20171226

- SafeSWormkeMInhibitory aryl hydrocarbon receptor-estrogen receptor α cross-talk and mechanisms of actionChem Res Toxicol20031680781612870882

- MocarelliPGerthouxMPattersonDGDioxin exposure, from infancy through puberty, produces endocrine disruption and affects human semen qualityEnviron Health Perspect2008116707718197302

- MocarelliPGerthouxPMNeedhamLLPerinatal exposure to low doses of dioxin can permanently impair human semen qualityEnviron Health Perspect201111971371821262597

- Abdel-ShafyHIMansourMSMPolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in indoor and outdoor environments and factors affecting their concentrationsEgypt J Petrol201625107123

- ZhuLTakahashiYAmagaiTMatsushitaHHighly sensitive automatic analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in indoor and outdoor airTalanta19974511311818966986

- World Health OrganizationWHO Guidelines for Indoor Air QualityGeneva, SwitzerlandWHO2010

- StraifKBaanRGrosseYSecretanBEl GhissassiFCoglianoVWHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working GroupCarcinogenicity of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonsLancet Oncol2005693193216353404

- ZhangYDongSWangHTaoSKiyamaRBiological impact of environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (ePAHs) as endocrine disruptorsEnviron Pollut201621380982427038213

- LewisRGPesticidesSpenglerJDMcCarthyJFSametJMIndoor Air Quality HandbookNew YorkMcGraw-Hill200135.135.17

- ButteWHeinzowBPollutants in house dust as indicators of indoor contaminationRev Environ Contam Toxicol200217514612206053

- SotoAMChungKLSonnenscheinCThe pesticides endosulfan, toxaphene, and dieldrin have estrogenic effects on human estrogen-sensitive cellsEnviron Health Perspect19941023803837925178

- SotoAMSonnenscheinCChungKLFernandezMFOleaNSerranoFOThe E-SCREEN assay as a tool to identify estrogens: an update on estrogenic environmental pollutantsEnviron Health Perspect1995103Suppl 7113122

- GareyJWolffMSEstrogenic and antiprogestagenic activities of pyrethroid insecticidesBiochem Biophys Res Commun19982518558599790999

- GoVGareyJWolffMSPogoBGEstrogenic potential of certain pyrethroid compounds in the MCF-7 human breast carcinoma cell lineEnviron Health Perspect199910717317710064545

- KimSSKwackSJLeeRDAssessment of estrogenic and androgenic activities of tetramethrin in vitro and in vivo assaysJ Toxicol Environ Health Part A2005682277228916326440

- KimSSLeeRDLimKJPotential estrogenic and antiandrogenic effects of permethrin in ratsJ Reprod Dev20055120121015599112

- JeongSHKimBYKangHGKuHOChoJHEffect of chlorpyrifosmethyl on steroid and thyroid hormones in rat F0- and F1-generationsToxicology200622018920216472551

- MeekerJDBarrDBHauserRThyroid hormones in relation to urinary metabolites of non-persistent insecticides in men of reproductive ageReprod Toxicol20062243744216584866

- World Health OrganizationGlyphosateEnvironmental Health Criteria 1994 Number 159. Available from: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc159.htm

- WalshLPMcCormickCMartinCStoccoDMRoundup inhibits steroidogenesis by disrupting steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein expressionEnviron Health Perspect2000108769776

- MesnageRPhedonosABiserniMEvaluation of estrogen receptor alpha activation by glyphosate-based herbicide constituentsFood Chem Toxicol2017108304228711546

- SouzaJSKizysMMLConceicaoRRPerinatal exposure to glyphosate-based herbicide alters the thyrotrophic axis and causes thyroid hormone homeostasis imbalance in male ratsToxicology2017377253727916585

- VandenbergLNBlumbergBAntoniouMNIs it time to reassess current safety standards for glyphosate-based herbicides?J Epidemiol Commun Health201771613618

- HayesTBAndersonLLBeasleyVRDemasculinization and feminization of male gonads by atrazine: consistent effects across vertebrate classesJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol2011127647321419222

- WirbiskySEFreemanJLAtrazine exposure and reproductive dysfunction through the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axisToxics2015341445028713818

- MajewskiMSCoupeRHForemanWTPesticides in Mississippi air and rain: a comparison between 1995 and 2007Environ Toxicol Chem2014331283129324549493

- DarbrePDMetalloestrogens: an emerging class of inorganic xenoestrogens with potential to add to the oestrogenic burden of the human breastJ Appl Toxicol20062619119716489580

- TanSYPraveenaSMAbidinEZCheemaMSA review of heavy metals in indoor dust and its human health-risk implicationsRev Environ Health20163144745627845887

- World Health OrganizationCadmiumEnvironmental Health Criteria 1992 Number 134. Available from: http://www.inchem.org/documents/ehc/ehc/ehc134.htm

- RaniAKumarALalAPantMCellular mechanisms of cadmium-induced toxicity: a reviewInt J Environ Health Perspect201424378399

- DarbrePDAluminium and the human breastMorphologie2016100657426997127

- RifatSLEastwoodMRMcLachlanDRCCoreyPNEffect of exposure of miners to aluminium powderLancet1990336116211651978033

- European Environment Agency (EEA)The impacts of endocrine disrupters on wildlife, people and their environmentsThe Wey-bridge+15 996–2011 reportLuxemburgPublications Office of the European Union2012

- BergmanAHeindelJJJoblingSKiddKAZoellerRTThe State of the Science of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals – 2012United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and World Health Organization (WHO)2013

- HoriguchiTMasculinization of female gastropod mollusks induced by organotin compounds, focusing on mechanism of actions of tributyltin and triphenyltin for development of imposexEnviron Sci200613778716788559

- JorundsdottirKSvavarssonJLeungKMImposex levels in the dogwhelk Nucella lapillus (L.) – continuing improvement at high latitudesMar Pollut Bull20055174474915894341

- GuilletteLJJrGundersonMPAlterations in development of reproductive and endocrine systems of wildlife populations exposed to endocrine-disrupting contaminantsReproduction200112285786411732981

- WeschlerCJNazaroffWWDermal uptake of organic vapors commonly found in indoor airEnviron Sci Technol2014481230123724328315

- NemeryBHoekPNemmarAThe Meuse Valley fog of 1930: an air pollution disasterLancet200135770470811247570

- BellMLDavisDDReassessment of the lethal London fog of 1952: novel indicators of acute and chronic consequences of acute exposure to air pollutionEnviron Health Perspect200110938939411427388

- KapoorDJonesTHSmoking and hormones in health and endocrine disordersEur J Endocrinol200515249149915817903

- TweedJOHsiaSHLutfyKFriedmanTCThe endocrine effects of nicotine and cigarette smokeTrends Endocrinol Metab20122333434222561025

- UtigerRDEffects of smoking on thyroid functionEur J Endocrinol19981383683699578499

- SeylerLEPomerleauOFFertigJBPituitary hormone response to cigarette smokingPharmacol Biochem Behav1986241591623945662

- GossainVVShermaNKSrivastavaLMichelakisAMRovnerDRHormonal effects of smoking – 11: effects on plasma cortisol, growth hormone and prolactinAm J Med Sci19862913253273010721

- WilkinsJNCarlsonHEVan VunakisHNicotine from cigarette smoking increases circulating levels of cortisol, growth hormone, and prolactin in male chronic smokersPsychopharmacology1982783053086818588

- WinternitzWWQuillenDAcute hormonal response to cigarette smokingJ Clin Pharmacol197717389397881471

- KirschbaumCWustSStrasburgerCJNormal cigarette smoking increases free cortisol in habitual smokersLife Sci1992504355421734161

- FrederickSLReusVIGinsbergDHallSMMunozRFEllmanGCortisol and response to dexamethasone as predictors of withdrawal distress and abstinence success in smokersBiol Psychiatry1998435255309547932

- CamlinNJMcLaughlinEAHoltJEThrough the smoke: use of in vivo and in vitro cigarette smoking models to elucidate its effect on female fertilityToxicol Appl Pharmacol201428126627525448442

- WindhamGCElkinESwanSHWallerKOFensterLCigarette smoking and effects on menstrual functionObstet Gynaecol1999935965

- KatoITonioloPKoenigKLEpidemiologic correlates with menstrual cycle length in middle aged womenEur J Epidemiol19991580981410608360

- ChioleroAFaehDPaccaudFCornuzJConsequences of smoking for body weight, body fat distribution, and insulin resistanceAm J Clin Nutr20088780180918400700

- VandenbergLNColbornTHayesTBHormones and endocrine-disrupting chemicals: low-dose effects and nonmonotonic dose responsesEndocr Rev20123337845522419778

- InoTMaternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring obesity: meta-analysisPediatr Int201052949919400912

- OkenELevitanEBGillmanMWMaternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: systematic review and meta analysisInt J Obes200832201210

- KoshyGDelpishehABrabinBJDose response association of pregnancy cigarette smoke exposure, childhood stature, overweight and obesityEur J Public Health20112128629121126981

- BruinJEGersteinHCHollowayACLong-term consequences of fetal and neonatal nicotine exposure: a critical reviewToxicol Sci201011636437420363831

- WoodsHFPhytoestrogens and HealthLondon, UKCrown Copyright, The Food Standards Agency2003

- MilliganSRKalitaJCHeyerickARongHDe CoomanLDe KeukeleireDIdentification of a potent phytoestrogen in hops (Humulus lupulus L.) and beerJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19998322492252

- SteinmannAHealth and societal effects from exposure to fragranced consumer productsPrevent Med Rep201754547

- HenleyDVLipsonNKorachKSBlochCAPrepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oilsN Engl J Med200735647948517267908

- KramerUHerderCSugiriDTraffic-related air pollution and incident type 2 diabetes: results from the SALIA cohort studyEnviron Health Perspect20101181273127920504758

- WeinmayrGHennigFFuksKHeinz Nixdorf Recall Investigator Group: Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a cohort study: effects of total and traffic-specific air pollutionEnviron Health2015145326087770

- WolfKPoppASchneiderAAssociation between long-term exposure to air pollution and biomarkers related to insulin resistance, subclinical inflammation, and adipokinesDiabetes2016653314332627605624

- HarrisRMMainwaringRHDiethylstilboestrol – a long-term legacyMaturitas20127210811222464649

- HuYWenSYuanDThe association between the environmental endocrine disruptor bisphenol A and polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysisGynecol Endocrinol Epub20171130

- CarreJGatimelNMoreauJParinaudJLéandriRDoes air pollution play a role in infertility?: a systematic reviewEnviron Health2017168228754128